Abstract

Background and purpose

Systemic inflammation contributes to diverse acute and chronic brain pathologies and extensive evidence implicates inflammation in stroke susceptibility and poor outcome. Here we investigate whether systemic inflammation alters cerebral blood flow (CBF) during reperfusion following experimental cerebral ischemia.

Methods

Serial diffusion and perfusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging was performed following reperfusion in Wistar rats given systemic (intraperitoneal) interleukin-1β (IL-1) or vehicle prior to 60min transient middle cerebral artery occlusion. The expression and location of endothelin-1 (ET-1) was assessed by PCR, ELISA and immunofluorescence.

Results

Systemic IL-1 caused a severe reduction in CBF and increase in infarct volume compared to vehicle. Restriction in CBF was observed alongside activation of the cerebral vasculature and upregulation of the vasoconstricting peptide ET-1 in the ischemic penumbra. A microthrombotic profile was also observed in the vasculature of rats receiving IL-1. Blockade of ET-1 receptors reversed this hypoperfusion, reduced tissue damage and improved functional outcome.

Conclusions

These data suggests patients with a raised inflammatory profile may have persistent deficits in perfusion after re-opening of an occluded vessel. Future therapeutic strategies to interrupt the mechanism identified could lead to enhanced recovery of penumbra in patients with a heightened inflammatory burden and a better outcome after stroke.

Keywords: inflammation, cerebral blood flow, cerebral ischemia, magnetic resonance imaging, interleukin-1

Introduction

A raised systemic inflammatory profile is observed in co-morbidities associated with vascular disease, including hypertension, infection, atherosclerosis, obesity and diabetes1-3. Observational clinical studies show that inflammation is independently associated with an increased risk of stroke as well as poor post-stroke outcomes4,5. Robust preclinical evidence shows that systemic inflammation markedly exacerbates acute brain injury6,7, but the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. The pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-1 (IL-1) is a major driver of inflammation and the detrimental effects of systemic IL-1 are well documented in multiple preclinical models of systemic inflammatory disease as well as in cerebral ischemia8-10.

Rapid restoration of cerebral blood flow (CBF) after acute ischemia, either spontaneously or through thrombolysis, reduces tissue damage. However, the benefit of reperfusion falls within a few hours of onset of ischemia, eventually becoming potentially harmful if timely reperfusion is not achieved11. Recanalization is an established reperfusion therapy for acute stroke12 however human imaging studies have shown that when recanalization is achieved it does not necessarily lead to restoration of tissue blood flow13. Restoration of CBF is likely to be more important than recanalization and consistent with this, tissue reperfusion has been shown to be a better predictor of recovery from stroke than recanalization14.

Pre-existing systemic inflammation may influence mechanisms needed to sustain adequate perfusion following stroke. Therefore, we have used a previously validated model15 of systemic inflammation to test the hypothesis that upregulation of vasoactive mediators may contribute to the observed association between inflammation and poor outcome following cerebral ischemia. We show that systemic IL-1 markedly increases the extent of tissue hypoperfusion following reperfusion, increased expression of endothelin-1 (ET-1) accompanies this hypoperfusion and that blockade of this mechanism results in restoration of CBF, reduced infarct and an improved outcome after experimental stroke.

Materials and methods

More detailed methods are available in the Online Data Supplemental section.

Animals

All experiments were performed using male, 9-week old, Wistar rats (350-450g) (Charles River Laboratories, UK) and adhered to the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act, UK (1986).

Focal cerebral ischemia

Focal cerebral ischemia was induced by transient (60min) middle cerebral artery occlusion (tMCAo) using a modification of the intraluminal filament model originally described by Longa et al16. Physiological parameters were recorded and homeostasis maintained. Mortality rate was <15% in all groups except where stated. Rats were transcardially-perfused with 0.9% saline followed by 4% paraformaldehyde or 0.1% Diethyl Pyrocarbonate (DEPC) treated sterile saline at the conclusion of experiments.

Treatment

Treatment allocations were randomized and blinded until completion of analysis. Rat recombinant IL-1β (4 μg/kg; National Institute for Biological Standards and Controls, UK) or vehicle (0.5% endotoxin-free bovine serum albumin in sterile PBS) was administered intraperitoneally at the onset of surgery and an intravenous dose of 1mg/kg of the selective ET-1 receptor A (ETrA) antagonist BQ-123 (Merck Chemicals Ltd, UK) was administered at occlusion and reperfusion. BQ-123 was chosen to ablate the activation of ETrA due to its potent and specific inhibition of ET-1 contractility in rat vascular smooth muscle17.

Assessment of neurological deficit

Neurological status and motor function were assessed blinded to drug treatment and according to the 28-point neuroscore, modified from methods previously described18.

MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed using a 7T horizontal bore magnet (Agilent, UK). Magnetic resonance angiography was used to assess occlusion and re-opening of the MCA. Lesion volume was determined from apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) maps. Perfusion weighted imaging (PWI) was performed using pseudo-continuous arterial spin labeling19,20.

MRI Analysis

Quantitative ADC maps were generated in Paravision 5 software (Bruker, Germany) from diffusion weighted images (DWI). A 23% reduction relative to mean contralateral ADC was used as the threshold to define the ischemic lesion21 (Java, General public license) and a 57% reduction relative to mean contralateral CBF was set as a threshold for hypoperfused tissue22. Physiological measurements were analyzed using MATLAB (MathWorks Inc, USA).

Histological analysis

The volume of ischemic damage and hemorrhagic transformation was measured by staining coronal sections (360μm interval) with cresyl violet (Sigma, UK) and hematoxylin & eosin (H&E).

RNA Extraction and quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR

Total RNA was extracted from isolated striatum and cortex brain homogenate using Trizol (Life Sciences, UK) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Detailed methods for the qPCR are described elsewhere23.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbant assay

ET-1 concentrations were determined by ELISA (R&D Systems, UK). Absorbance was measured using a plate reader (MRX, Dynatech, UK) at room temperature, and results were calculated from the standard curve using Prism 6 software (GraphPad, USA).

Immunofluorescence

Free floating coronal brain slices (30μm) were processed after tMCAo and immunofluorescence, microscopy and image analysis was performed as described in online data supplement.

Statistics

Group sizes (n=6-8) were calculated based on previous data. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Student’s t-test was used for single comparisons and one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was followed by Bonferroni’s correction for multiple comparisons or Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s test for multiple comparisons using Prism Graph 6.0 software (GraphPad Software, USA). Differences were considered significant when P<0.05.

Results

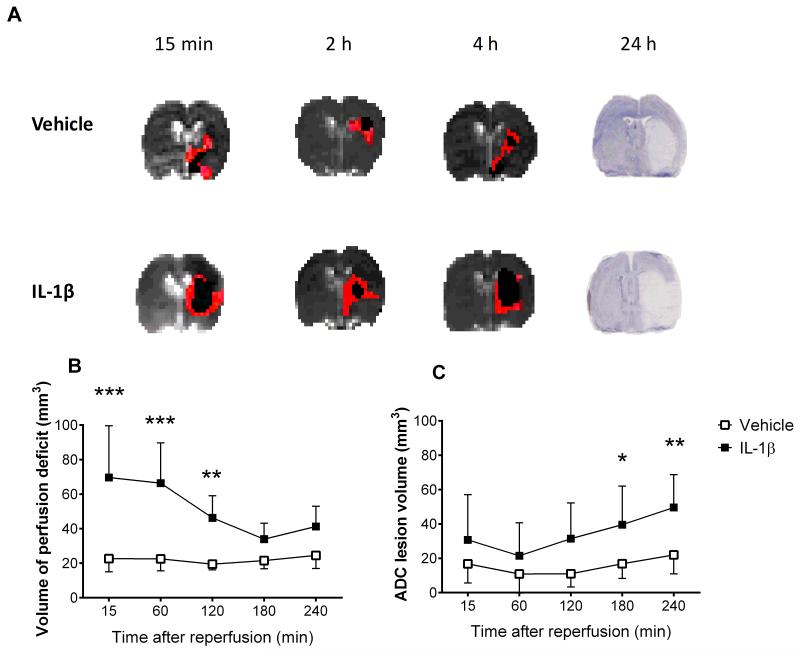

Acute systemic inflammatory challenge lowered CBF and worsened ischemic damage

Systemic inflammation induced by peripheral administration of IL-1β, resulted in larger infarct volumes at 24h (vehicle: 66±19mm3; IL-1β: 166±32mm3; *P<0.05) (Fig. 1A). IL-1β treated animals had a 3-fold higher volume of hypoperfused tissue 15min after re-opening the MCA, versus vehicle (vehicle: 22±7mm3; IL-1β: 70±30mm3; ***P<0.001) (Fig. 1B). The volume of hypoperfused tissue in IL-1β treated animals remained significantly higher up to 2h after MCA re-opening. Treatment with IL-1β did not alter CBF in sham treated animals (data not shown). ADC-derived lesion volumes were significantly higher (2-fold) in IL-1β treated compared to vehicle treated rats at 3 and 4h reperfusion (**P<0.01) (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1. The effects of systemic inflammation on cerebral blood flow.

Systemic inflammation was induced by i.p. IL-1β and effects on infarct DWI-PWI were assessed after tMCAo. (A) Representative ADC maps with hypoperfused volume (red) and infarct core (black) overlaid, highlighted the mismatch between infarct (DWI) and CBF deficit (PWI) at 15min, 2h and 4h after reperfusion in vehicle (top) and IL-1β treated animals (bottom). Cresyl violet staining shows infarct at 24h in vehicle and IL-1β treated rats. Acute evolution of perfusion deficit (B) and ADC derived ischemic lesion volume (C) in vehicle and IL-1β treated animals following 60min MCAo (two-way repeated measures ANOVA, Bonferroni post test). Data are presented as mean ± SD (n=8) ***P<0.001, **P<0.01, *P<0.05.

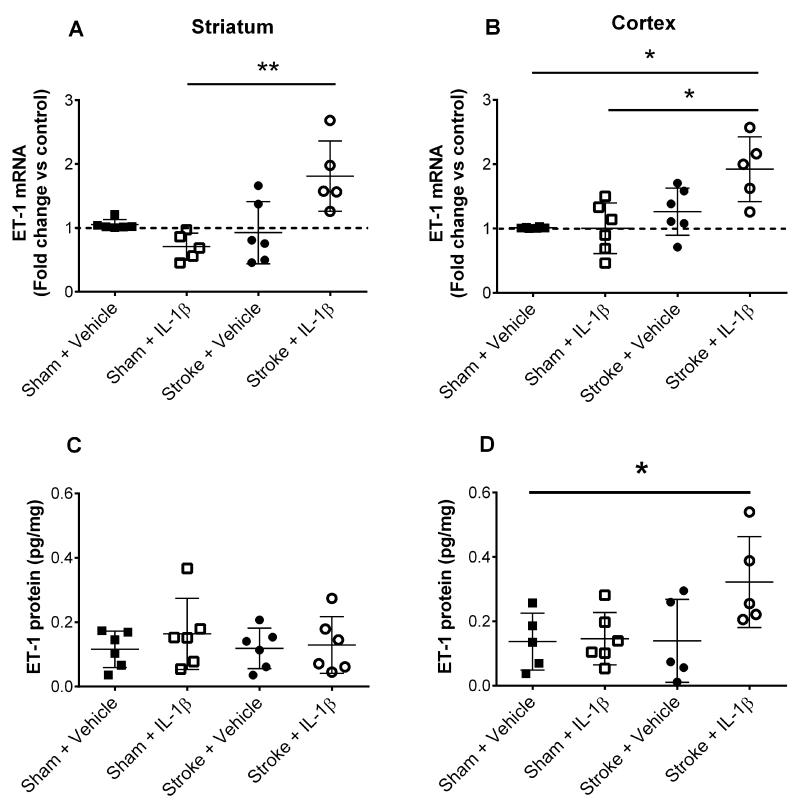

Upregulation of endothelin-1 mRNA and protein was associated with larger perfusion deficits in animals with systemic inflammatory challenge

Of the vasoactive mediators studied (supplementary Fig. I), a 2-fold increase in endothelin-1 (ET-1) mRNA expression was observed in the ipsilateral striatum (**P<0.01) and cortex (*P<0.05) of stroke+IL-1β versus sham and vehicle treated counterparts (Fig. 2A&B). A 2-fold increase (*P<0.05) in protein expression of ET-1 was measured in the cortex of IL-1β treated MCAo animals (Fig 2C&D).

Figure 2. Expression of early vasoactive mediators.

Vasoactive mediator expression was studied in animals receiving vehicle or IL-1β. Brains collected 15min after reperfusion were dissected, homogenized and qPCR performed. mRNA expression of ET-1 (A, B) were quantified and are shown as fold change from control (sham animals treated with vehicle). Protein levels of ET-1 (C, D) were measured in homogenized cortex and striatum at 15min reperfusion by ELISA. (One-way ANOVA, Dunn’s multiple comparison test) Data are presented as mean ± SD. Scale bar = 50μm. (A-D n=6). **P<0.01, *P<0.05.

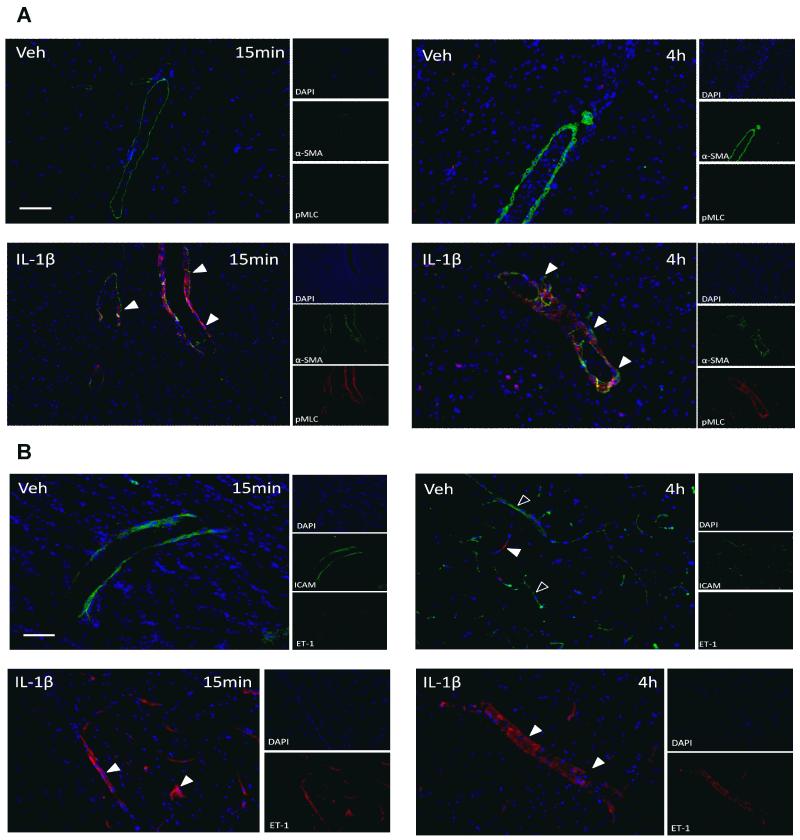

ET-1 receptor A is localized to smooth muscle in areas of perfusion deficits

Phosphorylated serine19 on myosin light chains (pMLC) (an integral step in brain endothelial cytoskeletal reorganization) and alpha smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) were co-localized in cortical arteries of IL-1β treated animals at 15min and 4h after cerebral ischemia alone (arrowhead Fig. 3A).

Figure 3. The effects of systemic inflammation on vascular smooth muscle.

Phosphorylated myosin light chain (pMLC) (red) immunoreactivity determined vasoconstriction in the ipsilateral hemisphere of MCAo animals at 15 min and 4h reperfusion in vehicle and IL-1β treated animals. pMLC was co-localized to alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) (green) in cortical surface arteries of animals treated with IL-1β only (arrowheads; A). Scale bar = 50μm. ET-1 expression was assessed in MCAo animals receiving vehicle or IL-1β. Vehicle treated animals exhibited ICAM-positive blood vessels only (green) (open arrowheads; B) in striatum and cortex at 15min reperfusion. Conversely, ET-1 (red) was observed in the vascular wall of IL-1β treated animals at 15min and 4h reperfusion (arrowhead; B). Scale bar = 50μm.

ET-1 (closed arrowhead Fig. 3B) was identified in animals receiving IL-1β prior to cerebral ischemia at both 15min and 4h after reperfusion, but in vehicle treated animals there was no ET-1 staining at 15min and minimal ET-1 staining at 4h. Vessels that stained positive for ET-1 also expressed endothelin-1 receptor A (ETrA) and were localized to the ipsilateral hemisphere of IL-1β treated animals (supplementary Fig. 2).

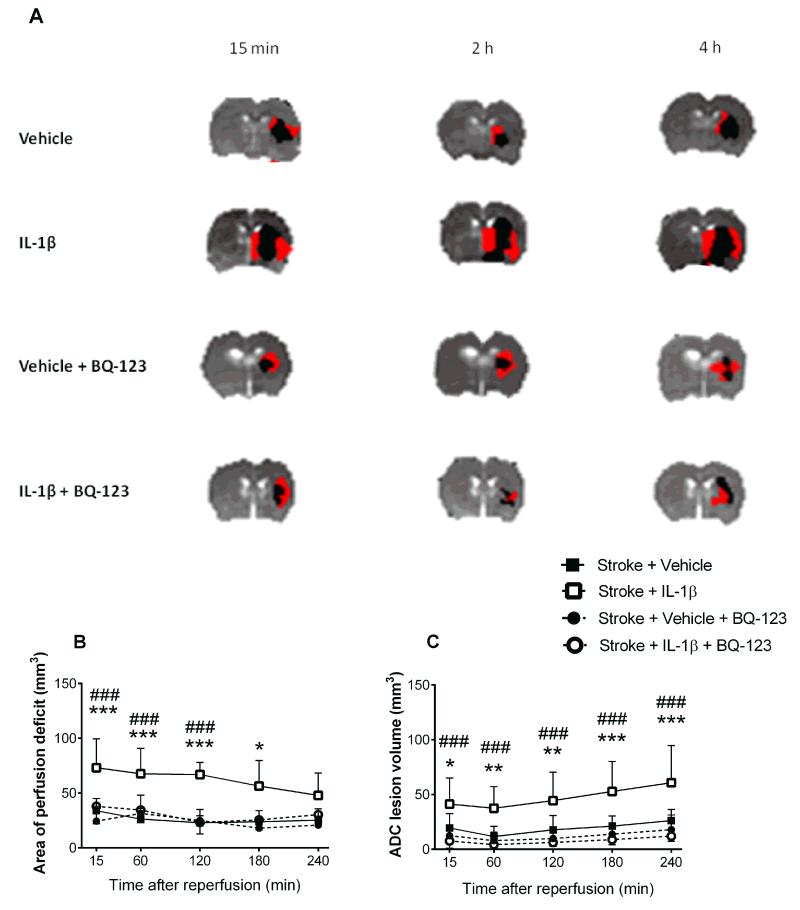

Inhibition of ET-1 receptor A prevented IL-1β induced hypoperfusion

A DWI-PWI mismatch was seen 15min, 2h, and 4h after MCAo in animals receiving vehicle, IL-1β, vehicle+BQ-123 or IL-1β+BQ-123 (Fig. 4A). Animals treated with IL-1β had a significantly larger perfusion deficit at 15min (vehicle: 33±11mm3; IL-1β: 73±26mm3; ***P<0.001). In contrast, in animals treated with IL-1β+BQ-123, the volume of hypoperfusion was reduced to levels seen in the vehicle treated group (IL-1β: 73±26mm3; IL-1β+BQ-123: 38±15mm3; ***P<0.001) (Fig. 4B). ADC derived lesion volume was larger in IL-1β treated than in vehicle treated rats at 4h reperfusion (vehicle: 26±10mm3; IL-1β: 60±34mm3; ***P<0.001). However, in animals treated with IL-1β+BQ-123, the volume of infarction was markedly reduced at 4h reperfusion (IL-1β: 73±26mm3; IL-1β+BQ-123: 38±15mm3; ***P<0.001), such that volumes were not significantly different to vehicle treated animals (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4. BQ-123 reverses hypoperfusion induced by systemic inflammation.

BQ-123 was used to antagonize ET-1 in rats receiving IL-1β or vehicle. (A) Representative ADC maps with hypoperfused volume (red) and infarct core (black) overlaid demonstrating DWI-PWI mismatch at 15min, 2h and 4h after reperfusion in vehicle, IL-1β, vehicle+BQ-123 and IL-1β+BQ-123 treated animals. Volume of hypoperfusion (B) and ADC lesion volumes (C) were determined at each time point and compared between groups. (Two-way repeated-measures ANOVA, Bonferroni post test). Data are presented as mean ± SD (n=8). ***P<0.001, **P<0.01, *P<0.05 in reference to stroke+IL-1β versus stroke+vehicle, ### P<0.001 in reference to stroke+IL-1β+BQ-123 versus stroke+IL-1β.

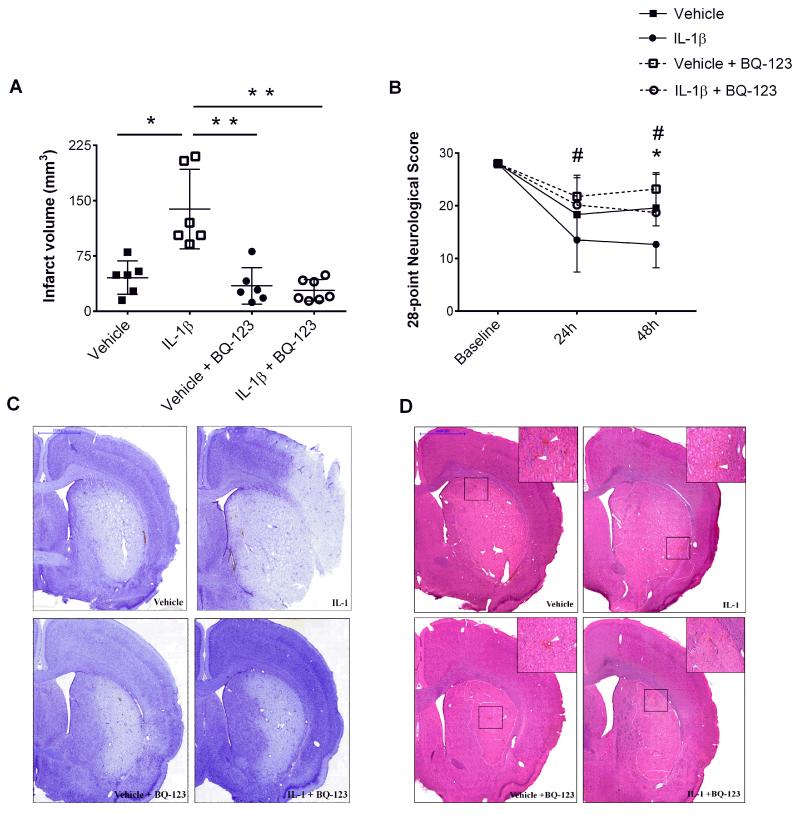

Blockade of ET-1 receptor A reduced ischemic damage and improved behavioral outcomes

Systemic IL-1β challenge prior to MCAo exacerbated the extent of ischemic brain injury (3-fold) and functional deficits at 48h reperfusion (Fig. 5A&B). Conversely, administration of BQ-123 in the presence of IL-1β and MCAo markedly attenuated (4-fold) ischemic damage and behavioral deficits (Fig. 5C). The incidence of HT (Fig. 5D) was not significantly increased in animals receiving BQ-123 (numbers of animals presenting with HT: vehicle, n= 2/6; IL-1β, n= 1/6; vehicle + BQ-123, n= 2/6; IL-1β + BQ-123, n= 1/7).

Figure 5. BQ-123 reverses IL-1β-induced ischemic damage and improves neurological outcomes.

Effects of BQ-123 on the extent of ischemic brain damage and behavioral and motor deficits were determined 48h after middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAo). The volume of ischemic damage (A) (One-way ANOVA, Dunn’s multiple comparison test) and the 28-point neuroscore (B) to assess sensorimotor deficits (two-way repeated measures ANOVA) was measured in animals receiving vehicle, IL-1β, vehicle+BQ-123 and IL-1β+BQ-123. Representative pictures from cresyl violet (C) and H&E stained tissue (D) 48h after MCAo illustrate differences in ischemic volume and hemorrhagic transformation (arrowheads). Data are presented as mean ± SD (n=6-7). Scale bar = 2000μm. **P<0.01, *P<0.05. Figure 5B: *P<0.05 in reference to stroke+IL-1β versus stroke+vehicle, #P<0.05 in reference to stroke+IL-1β+BQ-123 versus stroke+IL-1β.

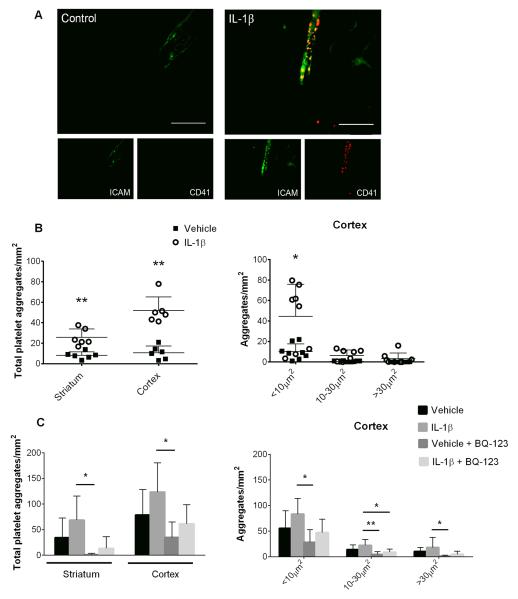

Acute systemic inflammatory challenge lowered CBF and was associated with a prothrombotic state

At 4h reperfusion, platelet CD41 positive immunostaining was seen within activated vessels of animals treated with systemic IL-1β (Fig. 6A). Presence of IL-1β was associated with significant accumulation of platelets (vehicle: 11±7 per mm2; IL-1β: 52±15 per mm2; **P<0.01) and formation of small aggregates (vehicle: 10±8 per mm2; IL-1β: 44±31 per mm2; *P<0.05) (Fig. 6B) in the cortex of IL-1β treated animals at 4h reperfusion. Treatment with BQ-123 did not completely deplete the number of platelets adhering to the endothelium at 4h reperfusion, though a trend towards reduction in platelet numbers was seen compared to IL-1β alone (IL-1β: 124±57 per mm2; IL-1β+BQ-123: 61±37 per mm2; P=0.068) (Fig. 6C). Blockade of ET-1 significantly reduced platelets in vehicle+BQ-123 treated animals (*P<0.05) and reduced platelet aggregates of <10μm2 and 10-30μm2 in vehicle+BQ-123 and IL-1β+BQ-123 treated animals at 4h reperfusion in the cortex (*P<0.05).

Figure 6. Systemic inflammation is associated with hypoperfusion and a prothrombotic state.

The effect of systemic IL-1β on platelet adhesion and aggregation was assessed after 60min ischemia. Immunofluorescence confirmed the presence of platelets in vessels of animals treated with IL-1β at 4h (A). Total numbers of platelets and aggregates at 4h reperfusion were counted (B) (Student’s t-test). Platelet numbers and aggregates were further analyzed in animals treated with vehicle+BQ-123 and IL-1β+BQ-123 at 4h (C) (two-way ANOVA, Bonferroni’s multiple-comparison post test). Scale bar = 50μm. Data expressed as average number of cells/mm2 in the predefined brain region and presented as mean ± SD. (n=5-6). **P<0.01, *P<0.05.

Discussion

We have shown that systemic IL-1β has a crucial role in limiting blood flow to metabolically compromised brain tissue and upregulation in ET-1 plays an important role in this process despite recanalization. Restoration of CBF during acute reperfusion was achieved through ETrA antagonism, leading to improved tissue survival and functional outcomes.

Clinical and experimental studies show an association between inflammation and a higher risk of ischemic stroke as well as worse post-stroke outcome24,25. Elevated IL-1β is a central component of these pathologies as seen in chronic and acute inflammatory models2,26, thus administration of systemic IL-1β is a relevant model for many conditions that predispose to stroke. It is thought that much of the detrimental actions of IL-1β on ischemic stroke are exerted peripherally as levels of IL-1β are undetectable in the brain10. Furthermore, IL-1β has been shown to affect the magnitude of the acute phase response which is a key indicator or peripheral inflammation. IL-1β causes an increase in C-reactive protein and IL-6, and in both preclinical10 and clinical studies27, raised levels of these markers are associated with poor prognosis. Peripherally administered lipopolysaccharide (LPS), which mimics aspects of infection, has also been used to represent acute inflammation prior to stroke and mice treated with LPS just prior to stroke show a marked increase in ischemic injury, an effect that is inhibited by administration of the IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra)10. Our recent data show that preceding pneumonia infection in mice also worsens ischemic brain damage, an effect dependent again on IL-1β as well as platelet-endothelial interactions28. This suggests endogenous IL-1β has a key role in exacerbation of ischemic damage by systemic inflammation, most likely through effects on the cerebrovasculature. Clinical relevance of these experimental findings is demonstrated by the finding that patients with pneumonia develop systemic cytokine responses and show raised levels of circulating IL-1β concentrations29,30. Previous studies have reported either no effect on blood vessel dynamics31 or a rise in cerebral blood volume32 in response to IL-1β, but in both studies IL-1β was administered in the absence of injury and it is likely that IL-1β acts differently in the presence of ischemia33,34. Our finding that ET-1 was upregulated only in animals exposed to both cerebral ischemia and an elevated inflammatory status and not in sham treated animals, lends further support to this hypothesis.

Smooth muscle cells have a critical role in regulating vascular tone in response to vasoactive mediators released by the endothelium35 and neighboring cells36. Previous experimental studies have shown the potent vasoconstrictive effects of ET-137 through its actions on ETrA on smooth muscle cells, in contrast to the predominantly vasodilatory ETrB that is abundant on endothelium and neurons38. Both ETrA and B are upregulated following injury39 but only blockade of ETrA before injury prevents hypoperfusion40. Whilst antagonism of ETrA restored CBF and reduced ischemic damage in animals with a pre-existing inflammatory challenge, infarct was not reduced in stroke+BQ-123 treated animals as seen in previous studies41. It is possible this discrepancy was due to the negligible volume of penumbral tissue remaining (as indicated by the DWI-PWI mismatch) for salvage by BQ-123. Furthermore, the observed increase in ET-1 expression and vessel contractility occurred primarily in the cortex of IL-1β treated animals. This co-localizes with tissue at risk of infarction and suggests that endothelin antagonism rescues penumbral tissue in the cortex rather than the necrotic infarct core of the striatum.

Despite differences in disease progression, hypoperfusion in both chronic and acute inflammatory conditions has been established in the experimental42,43 and clinical setting44. In patients with multiple sclerosis, an increase in plasma ET-1 was noted alongside a corresponding reduction in CBF as measured by PWI, while post-mortem studies show an upregulation of ET-1 in the brain parenchyma in MS45. The vasoconstrictive actions of endothelium-derived ET-1 on smooth muscle are well elucidated but here we report that the presence of systemic IL-1β acts as a trigger for vessel contractility via ET-1 following cerebral ischemia. It is possible IL-1β activates the endothelium to increase production of ET-1 as both ischemic stroke and IL-1 are potent activators of the cerebrovasculature46 and endothelial cells are a source of ET-147. Although we cannot rule out that other vasoactive mediators might contribute to reductions in CBF in the presence of systemic inflammation, our data do support an important, selective role for ET-1.

Our findings may have clinical implications beyond representing a mechanistic explanation for the worse outcome observed in stroke patients with a pre-existing elevated inflammatory status. Currently, recanalization represents a strong predictor of stroke outcome and is being increasingly used as a surrogate marker for efficacy in thrombolytic and other recanalization trials in acute stroke13,48. However, we have shown that an elevated systemic inflammatory profile can result in hypoperfusion and subsequent excess ischemic damage. This was prevented by BQ-123, therefore suggesting that recanalization does not necessarily lead to brain tissue reperfusion and that an elevated inflammatory status may be an important complimentary therapeutic target for stroke patients.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that systemic inflammation may worsen outcomes after cerebral ischemia by IL-1β-induced hypoperfusion in the presence of ET-1 during early reperfusion. This reduction in CBF leads to larger infarcts and worse functional outcomes despite large vessel recanalization. Interrupting this mechanism pharmacologically may improve recovery of CBF after thrombolysis or intra-arterial recanalization in patients with a high peripheral inflammatory burden, potentially improving outcomes after clinical stroke.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ms Karen Davies and Dr Duncan Hodkinson for technical support. We would also like to thank Professor Nancy Rothwell, Dr Jacqueline Ohanian, Dr Vasken Ohanian and Dr Chris McCabe for advice. We would like to thank the Bioimaging Facility for their help with microscopy.

Sources of funding

This work was supported by the Neuroscience Research Institute, Biomedical Imaging Institute and Medical Research Council, United Kingdom. This work was made possible by an equipment grant from BBSRC (BB/F011350), which funded the imaging console used in this study.

Footnotes

Disclosure

None.

References

- 1.Drake C, Boutin H, Jones MS, Denes A, McColl BW, Selvarajah JR, et al. Brain inflammation is induced by co-morbidities and risk factors for stroke. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2011;25:1113–22. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pradillo JM, Denes A, Greenhalgh AD, Boutin H, Drake C, McColl BW, et al. Delayed administration of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist reduces ischemic brain damage and inflammation in comorbid rats. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32:1810–9. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glynn RJ, Danielson E, Fonseca FAH, Genest J, Gotto AM, Kastelein JJP, et al. A randomized trial of rosuvastatin in the prevention of venous thromboembolism. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:1851–1861. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Selvarajah JR, Smith CJ, Hulme S, Georgiou R, Sherrington C, Staniland J, et al. Does inflammation predispose to recurrent vascular events after recent transient ischaemic attack and minor stroke? The North West of England transient ischaemic attack and minor stroke (NORTHSTAR) study. Int. J. Stroke. 2011;6:187–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2010.00561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tiainen M, Meretoja A, Strbian D, Suvanto J, Curtze S, Lindsberg PJ, et al. Body temperature, blood infection parameters, and outcome of thrombolysis-treated ischemic stroke patients. Int. J. Stroke. 2013;8:632–638. doi: 10.1111/ijs.12039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herz J, Hagen SI, Bergmüller E, Sabellek P, Göthert JR, Buer J, et al. Exacerbation of ischemic brain injury in hypercholesterolemic mice is associated with pronounced changes in peripheral and cerebral immune responses. Neurobiol. Dis. 2014;62:456–468. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2013.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gan Y, Liu Q, Wu W, Yin J-X, Bai X-F, Shen R, et al. Ischemic neurons recruit natural killer cells that accelerate brain infarction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014;111:2704–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1315943111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dénes A, Humphreys N, Lane TE, Grencis R, Rothwell N. Chronic systemic infection exacerbates ischemic brain damage via a CCL5 (regulated on activation, normal T-cell expressed and secreted)-mediated proinflammatory response in mice. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:10086–10095. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1227-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fan X, Lo EH, Wang X. Effects of minocycline plus tissue plasminogen activator combination therapy after focal embolic stroke in type 1 diabetic rats. Stroke. 2013;44:745–752. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.000309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McColl BW, Rothwell NJ, Allan SM. Systemic inflammatory stimulus potentiates the acute phase and CXC chemokine responses to experimental stroke and exacerbates brain damage via interleukin-1- and neutrophil-dependent mechanisms. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:4403–4412. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5376-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grotta J. Timing of thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke: “timing is everything” or “everyone is different.”. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2012;1268:141–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nam J, Jing H, O’Reilly D. Intra-arterial thrombolysis vs. standard treatment or intravenous thrombolysis in adults with acute ischemic stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Stroke. 2013:1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2012.00914.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Silva DA, Fink JN, Christensen S, Ebinger M, Bladin C, Levi CR, et al. Assessing reperfusion and recanalization as markers of clinical outcomes after intravenous thrombolysis in the echoplanar imaging thrombolytic evaluation trial (EPITHET) Stroke. 2009;40:2872–2874. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.543595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soares BP, Tong E, Hom J, Cheng SC, Bredno J, Boussel L, et al. Reperfusion is a more accurate predictor of follow-up infarct volume than recanalization: A proof of concept using CT in acute ischemic stroke patients. Stroke. 2010;41:e34–40. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.568766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McColl BW, Rothwell NJ, Allan SM. Systemic inflammation alters the kinetics of cerebrovascular tight junction disruption after experimental stroke in mice. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:9451–9462. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2674-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Longa EZ, Weinstein PR, Carlson S, Cummins R. Reversible middle cerebral artery occlusion without craniectomy in rats. Stroke. 1989;20:84–91. doi: 10.1161/01.str.20.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guo X, Okada K, Fujita N, Ishikawa S, Komatsu N, Saito T. Inhibitory effect of BQ-123 on endothelin-1-stimulated mitogen-activated protein kinase and cell growth of rat vascular smooth muscle cells. Hypertens. Res. 1996;19:23–30. doi: 10.1291/hypres.19.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lenzlinger PM, Saatman KE, Hoover RC, Cheney JA, Bareyre FM, Raghupathi R, et al. Inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) signaling by BSF476921 attenuates regional cerebral edema following traumatic brain injury in rats. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2004;22:73–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moffat BA, Chenevert TL, Hall DE, Rehemtulla A, Ross BD. Continuous arterial spin labeling using a train of adiabatic inversion pulses. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2005;21:290–296. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baskerville TA, McCabe C, Weir CJ, Macrae IM, Holmes WM. Noninvasive MRI measurement of CBF: evaluating an arterial spin labelling sequence with 99mTc-HMPAO CBF autoradiography in a rat stroke model. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32:973–7. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meng X, Fisher M, Shen Q, Sotak CH, Duong TQ. Characterizing the Diffusion/Perfusion Mismatch in Experimental Focal Cerebral Ischemia. Ann. Neurol. 2004;55:207–212. doi: 10.1002/ana.10803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shen Q, Fisher M, Sotak CH, Duong TQ. Effects of reperfusion on ADC and CBF pixel-by-pixel dynamics in stroke: characterizing tissue fates using quantitative diffusion and perfusion imaging. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2004;24:280–290. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000110048.43905.E5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lopez-Castejón G, Baroja-Mazo A, Pelegrín P. Novel macrophage polarization model: From gene expression to identification of new anti-inflammatory molecules. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2011;68:3095–3107. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0609-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kammersgaard LP, Jørgensen HS, Reith J, Nakayama H, Houth JG, Weber UJ, et al. Early infection and prognosis after acute stroke: the Copenhagen Stroke Study. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2001;10:217–21. doi: 10.1053/jscd.2001.30366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rewell SSJ, Fernandez JA, Cox SF, Spratt NJ, Hogan L, Aleksoska E, et al. Inducing stroke in aged, hypertensive, diabetic rats. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30:729–733. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Denes A, Drake C, Stordy J, Chamberlain J, McColl BW, Gram H, et al. Interleukin-1 mediates neuroinflammatory changes associated with diet-induced atherosclerosis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2012;1:e002006. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.112.002006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith CJ, Emsley HCA, Gavin CM, Georgiou RF, Vail A, Barberan EM, et al. Peak plasma interleukin-6 and other peripheral markers of inflammation in the first week of ischaemic stroke correlate with brain infarct volume, stroke severity and long-term outcome. BMC Neurol. 2004;4:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dénes Á , Pradillo JM, Drake C, Sharp A, Warn P, Murray KN, et al. Streptococcus pneumoniae worsens cerebral ischemia via interleukin 1 and platelet glycoprotein Ibα. Ann. Neurol. 2014;75:670–83. doi: 10.1002/ana.24146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rupp J, Kothe H, Mueller A, Maass M, Dalhoff K. Imbalanced secretion of IL-1beta and IL-1RA in Chlamydia pneumoniae-infected mononuclear cells from COPD patients. Eur. Respir. J. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Clin. Respir. Physiol. 2003;22:274–279. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00007303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Endeman H, Meijvis SC a, Rijkers GT, van Velzen-Blad H, van Moorsel CHM, Grutters JC, et al. Systemic cytokine response in patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Eur. Respir. J. 2011;37:1431–8. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00074410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beasley D, Cohen RA, Levinsky NG. Interleukin 1 inhibits contraction of vascular smooth muscle. J. Clin. Invest. 1989;83:331–335. doi: 10.1172/JCI113879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blamire AM, Anthony DC, Rajagopalan B, Sibson NR, Perry VH, Styles P. Interleukin-1beta -induced changes in blood-brain barrier permeability, apparent diffusion coefficient, and cerebral blood volume in the rat brain: a magnetic resonance study. J Neurosci. 2000;20:8153–8159. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-21-08153.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maher CO, Anderson RE, Martin HS, McClelland RL, Meyer FB. Interleukin-1beta and adverse effects on cerebral blood flow during long-term global hypoperfusion. J. Neurosurg. 2003;99:907–912. doi: 10.3171/jns.2003.99.5.0907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dorrance AM. Interleukin 1-beta (IL-1beta) enhances contractile responses in endothelium-denuded aorta from hypertensive, but not normotensive, rats. Vascul. Pharmacol. 2007;47:160–165. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang X, Yeung PKK, McAlonan GM, Chung SSM, Chung SK. Transgenic mice over-expressing endothelial endothelin-1 show cognitive deficit with blood-brain barrier breakdown after transient ischemia with long-term reperfusion. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2013;101:46–54. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Faraci FM, Heistad DD. Regulation of large cerebral arteries and cerebral microvascular pressure. Circ. Res. 1990;66:8–17. doi: 10.1161/01.res.66.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Macrae IM, Robinson MJ, Graham DI, Reid JL, McCulloch J. Endothelin-1-induced reductions in cerebral blood flow: dose dependency, time course, and neuropathological consequences. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1993;13:276–284. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1993.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Adner M, You J, Edvinsson L. Characterization of endothelin-A receptors in the cerebral circulation. Neuroreport. 1993;4:441–443. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199304000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kallakuri S, Kreipke CW, Schafer PC, Schafer SM, Rafols JA. Brain cellular localization of endothelin receptors A and B in a rodent model of diffuse traumatic brain injury. Neuroscience. 2010;168:820–830. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kreipke CW, Schafer PC, Rossi NF, Rafols JA. Differential effects of endothelin receptor A and B antagonism on cerebral hypoperfusion following traumatic brain injury. Neurol. Res. 2010;32:209–214. doi: 10.1179/174313209X414515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Briyal S, Gulati A. Endothelin-A receptor antagonist BQ123 potentiates acetaminophen induced hypothermia and reduces infarction following focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2010;644:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.06.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li W, Prakash R, Chawla D, Du W, Didion SP, Filosa J a, et al. Early effects of high-fat diet on neurovascular function and focal ischemic brain injury. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2013;304:R1001–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00523.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Palomares SM, Gardner-Morse I, Sweet JG, Cipolla MJ. Peroxynitrite decomposition with FeTMPyP improves plasma-induced vascular dysfunction and infarction during mild but not severe hyperglycemic stroke. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32:1035–1045. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Le Heron CJ, Wright SL, Melzer TR, Myall DJ, Macaskill MR, Livingston L, et al. Comparing cerebral perfusion in Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease dementia: an ASL-MRI study. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2014:1–7. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.D’Haeseleer M, Beelen R, Fierens Y, Cambron M, Vanbinst A, Verborgh C, et al. Cerebral hypoperfusion in multiple sclerosis is reversible and mediated by endothelin-1. PNAS. 2013;110:5654–5658. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222560110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thornton P, McColl BW, Greenhalgh A, Denes A, Allan SM, Rothwell NJ. Platelet interleukin-1α drives cerebrovascular inflammation. Blood. 2010;115:3632–3639. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-252643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaundal RK, Deshpande TA, Gulati A, Sharma SS. Targeting endothelin receptors for pharmacotherapy of ischemic stroke: Current scenario and future perspectives. Drug Discov. Today. 2012;17:793–804. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2012.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Griebe M, Kern R, Eisele P, Sick C, Wolf ME, Sauter-Servaes J, et al. Continuous magnetic resonance perfusion imaging acquisition during systemic thrombolysis in acute stroke. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2013;35:554–559. doi: 10.1159/000351146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.