Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), a highly malignant disease and the third leading cause of all cancer mortalities worldwide, often responses poorly to current treatments and results in dismal outcomes due to frequent chemoresistance and tumor relapse. The heterogeneity of HCC is an important attribute of the disease. It is the outcome of many factors, including the cross-talk between tumor cells within the tumor microenvironment and the acquisition and accumulation of genetic and epigenetic alterations in tumor cells. In addition, there is accumulating evidence in recent years to show that the malignancy of HCC can be attributed partly to the presence of cancer stem cell (CSC). CSCs are capable to self-renew, differentiate and initiate tumor formation. The regulation of the stem cell-like properties by several important signaling pathways have been found to endow the tumor cells with an increased level of tumorigenicity, chemoresistance, and metastatic ability. In this review, we will discuss the recent findings on hepatic CSCs, with special emphasis on their putative origins, relationship with hepatitis viruses, regulatory signaling networks, tumor microenvironment, and how these factors control the stemness of hepatic CSCs. We will also discuss some novel therapeutic strategies targeted at hepatic CSCs for combating HCC and perspectives of future investigation.

Keywords: liver cancer, microenvironment, signaling, therapeutic targeting, tumor-initiating cells

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) ranks the fifth most frequently diagnosed malignancy and the third leading cause of all cancer mortalities worldwide (Altekruse et al., 2009; Jemal et al., 2011). Individuals with chronic infections of hepatitis B or C viruses, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) as well as cirrhosis are the most common preceding conditions leading to HCC. Chemoresistance and frequent tumor relapse have been the major challenges hampering treatment efficacy. Similar to other cancers, HCC is heterogeneous in terms of cellular morphology, molecular profiles and clinical outcome. HCC heterogeneity is believed to be the outcome of combinatorial effects, including the acquisition of genetic and epigenetic alterations in tumor cells, the cross-talk of cells within the tumor microenvironment, as well as the existence of a cancer stem cell (CSC) subpopulation that has the ability to self-renew and differentiate. To date, liver CSCs have been identified based on various cell surface markers including epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM) (Yamashita et al., 2009), CD133 (Ma et al., 2007; 2010), CD90 (Yang et al., 2008), CD44 (Mima et al., 2012), CD24 (Lee et al., 2011), CD13 (Haraguchi et al., 2010), oval cell marker OV6 (Yang et al., 2012), calcium channel α2δ 1 isoform5 (Zhao et al., 2013) and CD47 (Lee et al., 2014a). Hoechst dye efflux (Chiba et al., 2006) and aldehyde dehydrogenase activities (Ma et al., 2008a) have also been used for liver CSCs isolation. These liver CSCs are governed by different signaling mechanisms in maintaining their tumorigenicity, chemoresistance and meta-static ability. Importantly, the presences of distinctive CSC populations that are endowed with differential functional characteristics suggest that a combination of targeted therapies will be necessary for successful cure of HCC. On the other hand, given the well-known etiological roles of chronic hepatitis viral B and C infection in HCC, recent studies have also revealed proteins encoded by these two viruses endow chronically infected hepatocytes or their progenitors with CSC-like properties, such as enhanced tumorigenicity, up-regulated expression of some CSC markers and activation of the relevant stemness signaling pathway (Arzumanyan et al., 2011; Li et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2012). This review summarizes recent discoveries relevant to liver CSCs, with emphasis on discussing their putative cellular origins, the roles of hepatitis viruses, tumor microenvironment and signaling network in controlling the stemness of CSCs. The novel therapeutic strategies and perspectives of future investigation will also be discussed.

CELLULAR ORIGINS OF HEPATIC CANCER STEM CELLS

Through extensive efforts by Holczbauer and colleagues, the origin of hepatic CSCs is starting to unveil. It appears that hepatic CSCs may well have arisen from populations of normal hepatocytes and some other specific liver lineages (Holczbauer et al., 2013).

It was suggested by Holczbauer et al. (2013) that hepatic CSCs can originate from cells of any of the three liver lineages - hepatic progenitor cells (HPCs), lineage-committed hepatoblasts (HBs), and differentiated adult hepatocytes (AHs). Their group was able to show that forced expression of H-Ras and SV40LT can transform these cells into CSCs.

Although various types of cells appear to have the potential of becoming hepatic CSCs, HPCs have the highest potential of undergoing oncogenic transformation compared to HBs or AHs (Holczbauer et al., 2013). In a limiting dilution analysis, injection of as few as 10 transduced HPCs is able to initiate tumors in 75% of all 8 injections, compared to 25% and 0% for transduced HBs and AHs, respectively (Holczbauer et al., 2013). When 100 cells were injected, tumors were generated from all HPC, HB and AH with an estimated tumor initiating frequency of 1/7, 1/26 and 1/42, respectively. The above studies demonstrated clearly that any hepatic lineage cell can, in the presence of genetic manipulation (Holczbauer et al., 2013), be transformed into hepatic CSCs that contributed to the initiation of aggressive liver cancers.

HEPATIC VIRUS AND HEPATIC CANCER STEM CELLS

Chronic infections of hepatitis B (HBV) or C viruses (HCV) are both prominent risk factors in the development of HCC (Bartosch et al., 2009; Levrero, 2006; Sun et al., 1999; Wurmbach et al., 2007). With the ever growing understanding of the importance of CSCs in the tumorigenesis of HCC, various groups have also begun investigating how HBV and HCV influence the malignant transformation of cells of various liver lineages into CSCs.

HBV-encoded X antigen (HBx) is implicated to be an important component in the occurrence and development of HBV-related HCC (Neuveut et al., 2010). This protein is believed to influence gene expression patterns, resulting in the up-regulation of many important genes involved in oncogenesis and proliferation (Tang et al., 2005). Recent studies (Arzumanyan et al., 2011; Li et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2012) have indicated that expression of HBx can enhance tumorigenic and stem cell-like properties of cells.

By using a 3,5-diethoxycarbonyl-1,4-dihydrocollidine (DDC)-induced liver injury model, EpCAM+ HPCs are activated in both the wild-type (WT) and HBx transgenic mice. After isolating and assaying the activated HPCs for their tumorigenicity in vivo, it was discovered that EpCAM+ HBx HPCs are more tumorigenic compared to EpCAM+ WT HPCs (Wang et al., 2012). Similarly, forced expression of HBx in other cell lines of liver lineages increased their tumorigenicity (Arzumanyan et al., 2011; Li et al., 2011).

This observation may be explained by a number of characteristics these HBx-expressing cells possess. A research group uses in vitro and in vivo studies to demonstrate that expression of HBx in liver cells could trigger “stemness” by stimulating the expression of various stem cell marker genes, including EpCAM and β-catenin (Arzumanyan et al., 2011). Another research group shows that the presence of aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) in the liver microenvironment and the expression of HBx in liver cells, in particular the HPCs or the oval cells, has significantly higher tumorigenic potential compared to the presence of either one of the two etiologic factors alone. The authors propose a reason to the above observation and suggest that the HBx-expressing cells are more sensitive to AFB1 and results in a higher incidence of mutation (Li et al., 2011).

The phenotypic changes of the HBx-expressing liver cells may be related to their altered gene expression patterns. Various groups have discovered the up regulation of β-catenin and interleukin-6 in HBx-expressing cells (Wang et al., 2012). It is therefore suggested that the increase in tumorigenicity, ‘stemness’, and decrease in apoptosis of HBx-expressing cells may be associated with the IL-6/STAT3, and Wnt/β-catenin pathways.

Chronic HCV infection is also another important risk factor in the development of HCC (Bartosch et al., 2009; Levrero, 2006; Wurmbach et al., 2007). Hepatoma cell lines with forced expression of a subgenomic replicon of HCV appear to acquire CSC characteristics, which were reversed when the cell lines were cured of the replicon. The CSC characteristics are shown as elevated expression levels of proteins including doublecortin and CaM kinase-like 1 (DCAMKL-1), Lgr5, CD133, and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP). These observations are substantiated by analysis using samples from HCV-positive patients (Ali et al., 2011). These results indicate a correlation between HCV infection and the acquisition of CSC characteristics in liver cells.

CYTOKINE NETWORK/TUMOR MICROENVIRONMENT AND HEPATIC CANCER STEM CELLS

In the course of identifying CD47+ HCC cells as chemoresistant tumor-initiating cells, Lee et al. (2014a) delineated an autocrine mechanism to explain the sustaining of stem-like properties in this HCC subpopulation. The CD47+ CSCs preferentially secreted cathepsin S (CTSS) and activated protease-activated receptor 2 (PAR2) through an autocrine loop, which facilitated the tumorigenic, metastatic and self-renewal ability of HCC in an NF-κB-dependent manner. IL-8 is another cytokine that has been found to be preferentially up-regulated by the CD133+ liver CSCs. IL-8 expression was associated with increased neurotensin (NTS) and CXCL1 and activated the MAPK signaling pathway in sustaining stemness and cancerous properties (Tang et al., 2012). He et al. (2013) isolated and characterized HCC progenitor cells (HPCs) from the livers of DEN-treated mice. These HPCs gave rise to tumors when injected into chronically damaged livers but not in normal livers. The group further identified the HPCs relied on autocrine IL-6 signaling via LIN28 up-regulation for malignant progression.

Cross-talk between tumor cells and infiltrated non-tumor cells also affects cancer stemness. A recent study showed that co-culturing of patient-derived CD14+ tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) promoted the expansion of CD44+ liver CSCs (Wan et al., 2014). In vitro self-renewal and xenograft tumor forming abilities of HCC cells were also enhanced by co-culturing with CD14+ TAMs. These intercellular signaling was mediated by IL-6 secreted by the TAMs and transduced through STAT3 in the recipient tumor cells. Another report using mouse macrophage cell suggested that TAM secreted TGF-β1 to induce mouse hepatoma cells to undergo epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and promoted their invasive phenotype (Fan et al., 2014). The study also reported a positive correlation between the number of TAMs and the density of CSCs in the margin of HCC clinical samples.

Chronic inflammation and fibrosis of the liver has been a well-known microenvironment fostering HCC development. The stiffness of these inflammatory and fibrotic tissues can be a measurable physical parameter of which the tumor microenvironment modulates the behavior of cancer cells. By using a matrix-coated polyacrylamide support that modeled the tumor stiffness across patho-physiological range, Schrader et al. (2011) showed that Huh7 and HepG2 cells proliferated faster when cultured on stiff than on soft supports. Culturing on stiff supports endowed the HCC cells with higher resistance to cisplatin. On the other hand, HCC cells cultured on soft supports revealed high clonogenic capacity, which was associated with increased abundance of CD133, CD44, CXCR4 and enhanced transcriptions of OCT4 and NANOG. These data suggested increasing stiffness of ECM has the potential to promote proliferation and chemoresistance, whereas decreasing ECM stiffness induced cellular dormancy and stemness of HCC cells.

In solid tumors, the pace of angiogenesis and the vessel network may not be efficient enough to nourish all tumor regions, such that nutrients and oxygen deprivation are environmental stresses challenging the cells within a tumor bulk. How CSCs in liver cancer cope with the hostile microenvironment is a field beginning to be explored. Two research groups have reported that CD133+ HCC cells made use of autophagy in maintaining their survival under nutrient-deprived and hypoxic environment (Chen et al., 2013a; 2013b).

SIGNALING NETWORKS AND HEPATIC CANCER STEM CELLS

The understanding of cellular signaling regulating the stemness and malignant phenotypes of hepatic cancer stem cells has advanced greatly in the past few years. In addition to the identification of developmental pathways and transcription factors implicated in regulating stem cell pluripotency de-regulated in liver CSC subpopulations, recent studies are also disclosing the importance of epigenetic regulators, microRNAs and metabolic enzymes in controlling the diverse properties of liver CSCs.

Wnt signaling has been implicated to play a critical etiological role in cancers arising from rapidly self-renewing tissues. In the case of the liver, Mokkapati et al. (2014) used β-catenin overexpressing transgenic mice specifically targeted at liver stem/progenitor cells to demonstrate that this stem cell regulatory pathway has a tumor initiating role in HCC. The 90% of all transgenic mice examined developed HCC by 26 weeks of age. Further, the HCC tumor showed activation of both Ras/Raf/MAPK and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways, as well as up-regulation of hepatic stem/progenitor cell markers including CITED1, DLK1, CD133, LGR5, SOX9, SOX4 and AFP (Mokkapati et al., 2014).

The role of TGF-β signaling in HCC development remains controversial. In a DEN-induced hepatocarcinogenesis rat model, the transcriptional level of TGF-β showed positive correlation with CD90, CD133 and EpCAM (Wu et al., 2012). TGF-β also conferred the rat liver progenitor cells with tumor-initiating cells properties, which was accompanied with activation of AKT and microRNA-216a mediated suppression of PTEN signaling. Whereas another study showed loss of TGF-β signaling in liver-restricted Pten and Tgfbr2 double knockout mice promoted HCC development. Histological analysis of the tumor tissues revealed up-regulated expression of CD133, in addition to EpCAM and c-Kit (CD117) (Morris et al., 2014).

A number of signaling pathways have now been implicated in the maintenance of stemness and cancerous properties of CD133+ liver CSCs. In particular, miRNA-130b was found to be preferentially up-regulated in CD133+ HCC cells and to be responsible in promoting CSC-like properties via silencing tumor protein 53 induced nuclear protein 1 (TP53INP1) (Ma et al., 2010). Overactivation of the Akt/PKB and Bcl-2 survival pathway has been identified to be employed by CD133+ liver CSCs to escape conventional chemotherapeutic agents (Ma et al., 2008b). Another study reported the CD133 subset to escape radiation exposure through MAPK/PI3K signaling activation and reduced reactive oxygen species levels (Piao et al., 2012). Ikaros has been known to suppress gene expression through recruiting promoter regions into pericentromeric heterochromatin. In HCC, decreased Ikaros expression was correlated with poor survival and the study by Zhang et al. (2014) showed that Ikaros exerted a tumor suppressive function through interacting with CtBP to form a transcriptional repressor complex that directly binds to the P1 promoter of CD133 such that the CSCs properties of HCC cells were suppressed (Zhang et al., 2014). TGF-β has also been suggested to regulate CD133 expression in HCC cells via inhibiting the expression of DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) 1 and DNMT3β, whereas Smad6 and Smad7 partially attenuated TGF-β1-induced CD133 expression (You et al., 2010). Interestingly, despite that the mTOR pathway is known for its tumorigenic functions through enhancing cell proliferation, inhibition of this pathway was found to increase the abundance of CD133+ cells and up-regulation of stemness markers. Moreover, inhibiting the mTOR signaling promoted the conversion of CD133− liver tumor cells to CD133+ cells (Yang et al., 2011). The CD133+ population of HCC cell lines has also been reported to contain higher levels of activated Ras, activated Ral and activated Aurora kinase (Ezzeldin et al., 2014).

Transcription factors that are known to maintain normal stem cell pluripotency also regulate stemness properties of liver CSCs. CD24+ HCC cancer stem cells were enriched in residual HCC cells resistant to cisplatin and relied on STAT3-mediated NANOG expression in maintaining CSC characteristics (Lee et al., 2011). Subsequent study identified Twist2, a transcription factor that mediates EMT, controlled CD24 expression in HCC cells by directly binding to the E-box region in the CD24 promoter. Thus, Twist2 regulates liver cancer stem-like cell self-renewal via the CD24-STAT3-NANOG axis (Liu et al., 2014). Pluripotency transcription factor Nanog marked liver CSCs and maintained their self-renewal through the IGF signaling pathway (Shan et al., 2012). Hypomethylation of NANOG promoter was detected in CD133+ liver cancer cells and ecotopic NANOG expression increased the abundance of CD133+ cells (Wang et al., 2013). Increased expression of OCT4 owing to DNA demethylation mediated chemoresistance in liver cancer through activating AKT-ABCG2 pathway (Wang et al., 2010). Zinc finger protein X-linked (ZFX), a transcription factor highly expressed in embryonic stem cells and hematopoietic stem cells, was recently reported to regulate CSC properties of HCC (Lai et al., 2014). ZFX is over-expressed in over half of HCC samples examined in the study and it carried out CSC regulatory roles through binding to promoters of NANOG and SOX2.

Aberrant functioning of metabolic pathways has also been recently shown to potentiate HCC development. Methionine adenosyltransferase (MAT) is the enzyme catalyzing S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) biosynthesis and its activity is known to diminish in chronically injured liver and HCC (Avila et al., 2000; Cai et al., 1996). Knockout of Mat1a in mice has been demonstrated to induce spontaneous HCC development by 18 months (Ding et al., 2009; Rountree et al., 2008). The CD133+CD49f+ and CD133+CD45− cell populations isolated from the HCC of Mat1a knockout mice showed CSC properties. CD133+CD49f+ cells could be clonally expanded and capable of initiating tumor formation (Rountree et al., 2008) and CD133+CD45− cells not only showed higher resistance to TGF-β induced apoptosis compared with CD133− cells, but also revealed a significant increase of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway. This Mat1a deficiency in vivo model demonstrated that interruption of the one-carbon cycle metabolism potentiates HCC development (Ding et al., 2009).

Epigenetic regulators are emerging candidates that play important functions in liver CSCs. Histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC3) expression was found to be up-regulated in HCC clinical samples and its expression correlated with poor prognosis (Liu et al., 2013a). Moreover, HCC cells that preferentially express HDAC3 revealed CSC properties including self-renewal and up-regulation of pluripotency factors. On the other hand, DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) was found to be a suppressor of HCC as its suppression enhanced the self-renewal and tumorigenicity of HCC cells (Marquardt et al., 2011; Raggi et al., 2014). Aberrant microRNA functions also plays a critical role in the maintenance of liver CSCs. MicroRNA profiling in HCC tissues identified significantly lowered expression of miR-148a in a subtype of HCC that is characterized by cancer stem-like cell signature. MiR-148a targets the BMP receptor ACVR1, whose overexpression has been associated with a dismal outcome of HCC patients (Li et al., 2014). MiR-142-3p was also recently found to regulate CD133 expression and its associated cancer stem cell properties (Chai et al., 2014). Recurrent HCC tissues have preferential overexpression of miR-216a/217 (Xia et al., 2013). MiR216a/217 silenced PTEN and SMAD7 expression, induced EMT, escalated EpCAM+ cell abundance and promoted resistance of HCC cells to sorafenib via augmenting the positive feedback of TGF-β and PI3K/Akt signaling cascades.

New insights of CSC regulatory mechanisms were also gained through studies of classic oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. A recent study characterized the role of the well-known oncogene c-MYC in regulating liver CSCs properties. Using a Tet-On system, Akita et al. (2014) showed that differential c-MYC expression in hepatoma cell lines have different effects of stem-cell like properties in HCC. At low level activation, c-MYC enhanced both in vitro and in vivo CSCs properties, which were accompanied with up-regulated expression of CSC maker genes, through a p53-dependent mechanism. When activated above an experimental threshold, c-MYC triggered apoptosis and abrogated CSC properties (Akita et al., 2014). Studies by Tschaharganeh et al. (2014) indicated that loss of p53 promotes dedifferentiation of mature hepatocytes into Nestin+ progenitor cells. Nestin, class IV intermediate filament protein, is a known marker of bi-potential liver progenitor cells (oval cells) that reside in the adult liver and expand upon chronic liver damage (Gleiberman et al., 2005). P53 suppressed Nestin expression through a Sp1/3-dependent mechanism.

THERAPEUTIC TARGETING OF HEPATIC CANCER STEM CELLS

The heterogeneous characteristics of HCC, frequent disease recurrence and the chemoresistance nature of the tumor imply the need of targeting the disease from different perspectives. In particular, a recent study demonstrated that CSCs from recurrent HCC patients can be isolated based on the expression of isoform 5 of the α2δ1 subunit of voltage-gated calcium channel. α2δ1 was further characterized as a functional tumor-initiating cell marker. Surgical margin of HCC containing cells detectable by 1B50-1 is predictive of tumor recurrence. The group generated a monoclonal antibody, 1B50-1, to target these CSCs, where IB50-1 exerted a promising therapeutic potential through eliminating CSCs from recurrent HCC (Zhao et al., 2013).

Chemoresistance is another challenge in HCC treatment. Some recent studies adopted a proactive approach to identify chemoresistant liver CSCs and their underlying molecular mechanisms in order to combat the ever evolving cancer cells. A recently published study indicated that CD47+ HCC cells were enriched in chemoresistant hepatospheres and these cells were endowed with CSC characteristics. The ability to chemo-sensitize these CSC upon CD47 suppression supported it as a novel therapeutic target for HCC treatment (Lee et al., 2014a).

Targeting dormant or slow cycling CSCs is important to avoid tumor relapse. By adopting Hoescht-dye exclusion approach, Haraguchi et al. (2010) identified CD13-expressing side population as a semi-quiescent CSC subpopulation in human HCC. These CD13+ liver CSCs displayed resistance to chemotherapeutic drugs, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and doxorubicin. Its chemoresistance was attributed to lower levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which protected ROS-induced DNA damage after exposure to genotoxic chemo/radiation stress. Further, it was demonstrated in mouse xenograft models that combination of CD13 inhibitor (ubenimex) and 5-FU led to drastic tumor regression compared with either agent alone. 5-FU alone suppressed proliferative CD90+ CSCs and some of which generated semi-quiescent CD13+ CSCs. The self-renewing and tumor-initiating potential of these dormant CSCs were inhibited by ubenimex. Thus, it was proposed that a combination of CD13 inhibition with ROS-inducing chemo/radiation therapy can improve treatment efficacy. Another study using orthotopic HCC mouse models by injection of human AFP and/or luciferase-expressing HCC cell lines and primary HCC cells also demonstrated that CD13+ cells were found in minimal residual disease, suggesting that targeting dormant CSCs is critical for treatment success (Martin-Padura et al., 2012).

Oncofetal proteins are another attractive class of therapeutic targets. Granulin-epithelin precursor (GEP) is an oncofetal protein found expressed in fetal livers but not normal adult livers (Cheung et al., 2011). GEP+ fetal liver cells expressed an array of embryonic stem cell-related signaling proteins including β-catenin, OCT4, NANOG, SOX2 and DLK1, and hepatic CSC markers CD133, EpCAM and ABCB5. GEP+ HCC clinical sample and cell lines also expressed these pluripotent molecules. The group further proposed that co-expression of GEP and ABCB5 enriched a subpopulation of liver CSCs that are rational therapeutic targets of HCC.

Sorafenib, a multikinase inhibitor targeting the ERK pathway, is the only FDA-approved drug for treatment of advanced HCC patients. However, sensitivity towards this drug varies among patients. A recent study found that the therapeutic response of HCC patients to sorafenib was inversely correlated with CD133 expression and JNK pathway activity. Using a JNK specific inhibitor, the group was able to reduce xenografted CD133+ cells in athymic mice (Hagiwara et al., 2012). These results highlight the necessity of perturbing pathways regulating the maintenance of CSCs in order to improve treatment outcome. Several other studies also support the therapeutic potential through targeting CD133 cells. CD133+ HCC cells have been shown to maintain their survival under hypoxic and nutrient-deprived environment via undergoing autophagy. In vitro data showed that inhibition of autophagy can significantly promote apoptosis while reducing the clonogenic potential of the CD133+ subset (Song et al., 2013). Another study also showed that CD133 promoted HCC cells autophagy under low glucose medium and that stable knockdown of CD133 also led to impaired glucose uptake. CD133 monoclonal antibody treatment inhibited autophagy while inducing apoptosis of HCC cells (Chen et al., 2013a). BMP4 has been tested and shown to be capable of promoting differentiation of CD133+ HCC cells and reduced both in vitro and in vivo cancer stem-like cells properties (Zhang et al., 2012). Oncolytic measles virus targeting CD133+ HCC cells has been shown to exert anti-tumoral effect on HCC growing subcutaneously or multifocally in the peritoneal cavity of nude mice (Bach et al., 2013).

Immunotherapy has also been proposed for targeting liver CSCs. The therapeutic efficacy of current dendritic cell (DC)-based vaccine against HCC remains limited. A recent study reported the development of a DC-based vaccine that acted against CD133+ HCC CSCs (Sun et al., 2010). The DCs used were loaded with RNA from CD133+ HCC cells and induced in vitro cytotoxic CD8+ T lymphocytes against CD133+ Huh7 cells (CD133+Huh7-CTLs). These primed CTLs inhibited the tumorigenic ability of Huh7 cells subcutaneously injected in nude mice. Recurrent HCC cells derived from the sample patient expressed higher levels of liver progenitor markers and showed enhanced tumorigenic capacity in serial transplantation assays (Xu et al., 2010). Furthermore, these recurrent HCC cells could be recognized and killed by autologous-activated tumor-infiltrated lymphocytes (TILs). Pre-treatment of the recurrent HCC cells with TNF-α and INF-γ potentiated in vitro CD8+ T-cell-mediated recognition and TILs-mediated cytotoxicity. These results supported the proposal of adopting immunotherapy to control recurrent HCC.

Since epigenetic mechanisms have been known to play essential roles in regulating CSC stemness, epigenetic regulators are another class of plausible therapeutic targets. EZH2 is required by HCC cells for self-renewal and its pharmacological inhibition by 3-deazaneplanocin (DNZep) reduced the level of EpCAM+ HCC CSCs. Moreover, DNZep exerted more potent effect than 5-FU in terms of suppressing the abundance of EpCAM+ CSCs (Chiba et al., 2012). HDAC inhibitors reduced HCC cells stemness. Further, knockdown of HDAC3, a histone deacetylase known to be preferentially expressed in liver CSCs, enhanced the sensitivity of HCC cells to sorafenib (Liu et al., 2013a). Chromatin modifier HDAC2, despite its unknown roles in CSCs, have also been recently suggested as therapeutic target for HCC (Lee et al., 2014b).

The well-known diabetic drug metformin has recently been shown to have anti-tumoral effect in various malignancies including HCC. A recent report revealed that metformin treatment reduced the abundance of EpCAM+ HCC cells, which was accompanied by impaired self-renewal capability of HCC cells (Saito et al., 2013). Small molecule inhibitor of aldehyde dehydrogenase, disulfiram, have been shown to down-regulate the abundance of CSC markers and suppress the self-renewal ability of HCC cells through activating the ROS-p38 MAPK pathway (Chiba et al., 2014). Targeting oxidative stress-elicited AKT activation down-regulated the stem-like cell properties but enhanced the inhibitory potency of PPARγ agonist. Combined application of AKT inhibitor and PPARγ agonist is believed to have the potential as HCC therapy (Liu et al., 2013b).

CONCLUSION

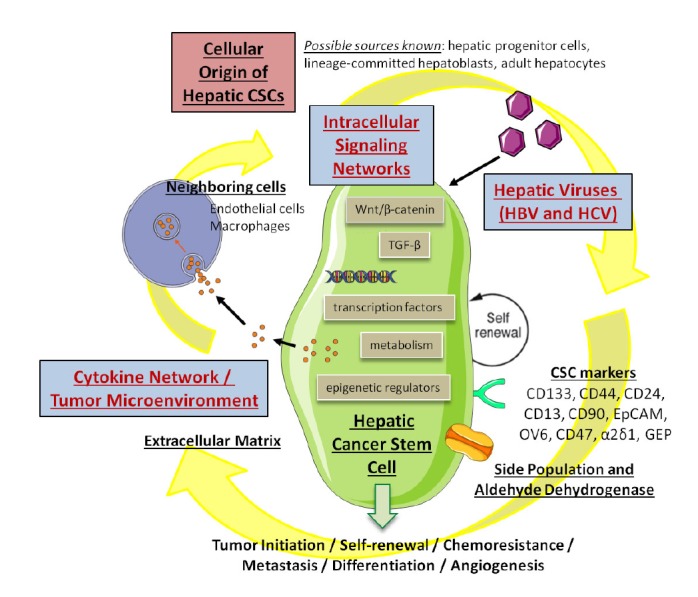

Although various liver cancer stem cells have been identified based on the expression of cell surface proteins and the underlying signaling mechanisms sustaining their perpetuation have been partially elucidated (Fig. 1), the relative significance of these CSCs in individual patient and at different disease stages remain obscure.

Fig. 1.

Our current knowledge of hepatic cancer stem cells gained from different perspectives.

There is increasing recognition and appreciation that tumors comprise of complex networks that resemble an intricate ecosystem where individual cells endowed with distinctive characteristics play different functional roles and co-operate to support the growth and maintenance of the whole tumor (Kreso and Dick, 2014). Driver mutations and heritable epigenetic changes give rise to different clones of tumor cells during the course of tumor formation, progression and metastasis. Topological biopsy of tumors followed by whole exome sequencing (WES) and whole genome sequencing (WGS) indicated the presence of intratumoral heterogeneity genetic subclones located in different regions of the same tumor. In breast cancers, based on the detection of genetic subclones within tumors, it is now possible to create the evolutionary lineage of these subclones such that the life histories of breast cancer could be reconstructed (Nik-Zainal et al., 2012). Thus, it was suggested that understanding the mechanisms driving evolution of tumors that give rise to genetically distinct subclones can help predict response to therapy and recurrence and/or metastasis (Kreso and Dick, 2014). These latest conception of tumor biology can also be applied to study the progression of HCC that lead to the advancement of patient management.

Disseminated tumor cells (DTCs) and tumor dormancy is another field with escalating interest. Even before diagnosis, some cancer cells are believed to have already migrated from the primary developing tumor to colonize secondary organs. These DTCs then enter dormancy and become the source of CSCs for recurrence, years after treatment (Sosa et al., 2014). Unfortunately, the current knowledge of DTC is too scarce when it comes to pinpointing the therapeutic paradigms of these quiescent cells. It is very likely that HCC and/or its pre-diagnostic stages release numerous DTCs to distant organs. These DTCs escape treatment and are responsible for tumor recurrence. Indeed, other than identifying CSCs from the tumor bulk, a research group prospectively isolated the circulating tumor cells (CTCs) from HCC patients (Sun et al., 2013). The group further discovered that some EpCAM+ CTCs showed stem cell-like properties. Moreover, the presence of ≥2 preoperative CTC per 7.5 ml of blood was shown to be a predictor of tumor recurrence in HCC patients, despite the fact that concrete roles of the EpCAM+ CTCs in tumor recurrence and metastasis were not addressed. Understanding the mechanisms governing the status of DTC will be a critical avenue for cancer biologists in achieving disease eradication.

Acknowledgments

We apologize to colleagues whose work was not cited due to space constraints. Work in our laboratory is supported by funding from the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong - General Research Fund/Early Career Scheme (HKU_774513M, HKU_773412M and 27101214), the Health and Medical Research Fund (12110792), the National Natural Science Foundation of China – Science Fund for Young Scholars (81302171) and the Croucher Innovation Award from the Croucher Foundation to S Ma. S Ma is supported by funding from the Outstanding Young Researcher Award Scheme at HKU. Steve T. Luk is supported by the University Postgraduate Fellowship from HKU.

REFERENCES

- Akita H., Marquardt J.U., Durkin M.E., Kitade M., Seo D., Conner E.A., Andersen J.B., Factor V.M., Thorgeirsson S.S. MYC activates stem-like cell potential in hepatocarcinoma by a p53-dependent mechanism. Cancer Res. 2014;74:5903–5913. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali N., Allam H., May R., Sureban S.M., Bronze M.S., Bader T., Umar S., Anant S., Houchen C.W. Hepatitis C virus-induced cancer stem cell-like signatures in cell culture and murine tumor xenografts. J. Virol. 2011;85:12292–12303. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05920-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altekruse S.F., McGlynn K.A., Reichman M.E. Hepatocellular carcinoma incidence, mortality, and survival trends in the United States from 1975 to 2005. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;27:1485–1491. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.7753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arzumanyan A., Friedman T., Ng I., Clayton M., Lian Z., Feitelson M. Does the hepatitis B antigen HBx promote the appearance of liver cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2011;71:3701–3708. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avila M.A., Berasain C., Torres L., Martin-Duce A., Corrales F.J., Yang H., Prieto J., Lu S.C., Caballeria J., Rodes J., et al. Reduced mRNA abundance of the main enzymes involved in methionine metabolism in human liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2000;33:907–914. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80122-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach P., Abel T., Hoffmann C., Gal Z., Braun G., Voelker I., Ball C.R., Johnston I.C., Lauer U.M., Herold-Mende C., et al. Specific elimination of CD133+ tumor cells with targeted oncolytic measles virus. Cancer Res. 2013;73:865–874. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartosch B., Thimme R., Blum H.E., Zoulim F. Hepatitis C virus-induced hepatocarcinogenesis. J. Hepatol. 2009;51:810–820. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai J., Sun W.M., Hwang J.J., Stain S.C., Lu S.C. Changes in S-adenosylmethionine synthetase in human liver cancer: molecular characterization and significance. Hepatology. 1996;24:1090–1097. doi: 10.1002/hep.510240519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai S., Tong M., Ng K.Y., Kwan P.S., Chan Y.P., Fung T.M., Lee T.K., Wong N., Xie D., Yuan Y.F., et al. Regulatory role of miR-142-3p on the functional hepatic cancer stem cell marker CD133. Oncotarget. 2014;5:5725–5735. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Luo Z., Dong L., Tan Y., Yang J., Feng G., Wu M., Li Z., Wang H. CD133/prominin-1-mediated autophagy and glucose uptake beneficial for hepatoma cell survival. PLoS One. 2013a;8:e56878. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Luo Z., Sun W., Zhang C., Sun H., Zhao N., Ding J., Wu M., Li Z., Wang H. Low glucose promotes CD133 mAb-elicited cell death via inhibition of autophagy in hepatocarcinoma cells. Cancer Lett. 2013b;336:204–212. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung P.F., Cheng C.K., Wong N.C., Ho J.C., Yip C.W., Lui V.C., Cheung A.N., Fan S.T., Cheung S.T. Granulin-epithelin precursor is an oncofetal protein defining hepatic cancer stem cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28246. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiba T., Kita K., Zheng Y.W., Yokosuka O., Saisho H., Iwama A., Nakauchi H., Taniguchi H. Side population purified from hepatocellular carcinoma cells harbors cancer stem cell-like properties. Hepatology. 2006;44:240–251. doi: 10.1002/hep.21227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiba T., Suzuki E., Negishi M., Saraya A., Miyagi S., Konuma T., Tanaka S., Tada M., Kanai F., Imazeki F., et al. 3-Deazaneplanocin A is a promising therapeutic agent for the eradication of tumor-initiating hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Int. J. Cancer. 2012;130:2557–2567. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiba T., Suzuki E., Yuki K., Zen Y., Oshima M., Miyagi S., Saraya A., Koide S., Motoyama T., Ogasawara S., et al. Disulfiram eradicates tumor-initiating hepatocellular carcinoma cells in ROS-p38 MAPK pathway-dependent and -independent manners. PLoS One. 2014;9:e84807. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding W., Mouzaki M., You H., Laird J.C., Mato J., Lu S.C., Rountree C.B. CD133+ liver cancer stem cells from methionine adenosyl transferase 1A-deficient mice demonstrate resistance to transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta-induced apoptosis. Hepatology. 2009;49:1277–1286. doi: 10.1002/hep.22743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezzeldin M., Borrego-Diaz E., Taha M., Esfandyari T., Wise A.L., Peng W., Rouyanian A., Asvadi Kermani A., Soleimani M., Patrad E., et al. RalA signaling pathway as a therapeutic target in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Mol. Oncol. 2014;8:1043–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2014.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Q.M., Jing Y.Y., Yu G.F., Kou X.R., Ye F., Gao L., Li R., Zhao Q.D., Yang Y., Lu Z.H., et al. Tumor-associated macrophages promote cancer stem cell-like properties via transforming growth factor-beta1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2014;352:160–168. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleiberman A.S., Encinas J.M., Mignone J.L., Michurina T., Rosenfeld M.G., Enikolopov G. Expression of nestin-green fluorescent protein transgene marks oval cells in the adult liver. Dev. Dyn. 2005;234:413–421. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagiwara S., Kudo M., Nagai T., Inoue T., Ueshima K., Nishida N., Watanabe T., Sakurai T. Activation of JNK and high expression level of CD133 predict a poor response to sorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma. Br. J. Cancer. 2012;106:1997–2003. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haraguchi N., Ishii H., Mimori K., Tanaka F., Ohkuma M., Kim H.M., Akita H., Takiuchi D., Hatano H., Nagano H., et al. CD13 is a therapeutic target in human liver cancer stem cells. J. Clin. Invest. 2010;120:3326–3339. doi: 10.1172/JCI42550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He G., Dhar D., Nakagawa H., Font-Burgada J., Ogata H., Jiang Y., Shalapour S., Seki E., Yost S.E., Jepsen K., et al. Identification of liver cancer progenitors whose malignant progression depends on autocrine IL-6 signaling. Cell. 2013;155:384–396. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holczbauer Á., Factor V.M., Andersen J.B., Marquardt J.U., Kleiner D.E., Raggi C., Kitade M., Seo D., Akita H., Durkin M.E., et al. Modeling pathogenesis of primary liver cancer in lineage-specific mouse cell types. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:221–231. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A., Bray F., Center M.M., Ferlay J., Ward E., Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreso A., Dick J.E. Evolution of the cancer stem cell model. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14:275–291. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai K.P., Chen J., He M., Ching A.K., Lau C., Lai P.B., To K.F., Wong N. Overexpression of ZFX confers self-renewal and chemoresistance properties in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer. 2014;135:1790–1799. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee T.K., Castilho A., Cheung V.C., Tang K.H., Ma S., Ng I.O. CD24(+) liver tumor-initiating cells drive self-renewal and tumor initiation through STAT3-mediated NANOG regulation. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9:50–63. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee T.K., Cheung V.C., Lu P., Lau E.Y., Ma S., Tang K.H., Tong M., Lo J., Ng I.O. Blockade of CD47-mediated cathepsin S/protease-activated receptor 2 signaling provides a therapeutic target for hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2014a;60:179–191. doi: 10.1002/hep.27070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y.H., Seo D., Choi K.J., Andersen J.B., Won M.A., Kitade M., Gomez-Quiroz L.E., Judge A.D., Marquardt J.U., Raggi C., et al. Antitumor effects in hepatocarcinoma of isoform-selective inhibition of HDAC2. Cancer Res. 2014b;74:4752–4761. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-3531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levrero M. Viral hepatitis and liver cancer: the case of hepatitis C. Oncogene. 2006;25:3834–3847. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C.H., Wang Y.J., Dong W., Xiang S., Liang H.F., Wang H.Y., Dong H.H., Chen L., Chen X.P. Hepatic oval cell lines generate hepatocellular carcinoma following transfection with HBx gene and treatment with aflatoxin B1 in vivo. Cancer Lett. 2011;311:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Liu Y., Guo Y., Liu B., Zhao Y., Li P., Song F., Zheng H., Yu J., Song T., et al. Regulatory miR-148a-ACVR1/BMP circuit defines a cancer stem cell-like aggressive subtype of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2014 doi: 10.1002/hep.27543. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C., Liu L., Shan J., Shen J., Xu Y., Zhang Q., Yang Z., Wu L., Xia F., Bie P., et al. Histone deacetylase 3 participates in self-renewal of liver cancer stem cells through histone modification. Cancer Lett. 2013a;339:60–69. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Yang Z., Xu Y., Li J., Xu D., Zhang L., Sun J., Xia S., Zou F., Liu Y. Inhibition of oxidative stress-elicited AKT activation facilitates PPARgamma agonist-mediated inhibition of stem cell character and tumor growth of liver cancer cells. PLoS One. 2013b;8:e73038. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu A.Y., Cai Y., Mao Y., Lin Y., Zheng H., Wu T., Huang Y., Fang X., Lin S., Feng Q., et al. Twist2 promotes self-renewal of liver cancer stem-like cells by regulating CD24. Carcinogenesis. 2014;35:537–545. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma S., Chan K.W., Hu L., Lee T.K., Wo J.Y., Ng I.O., Zheng B.J., Guan X.Y. Identification and characterization of tumorigenic liver cancer stem/progenitor cells. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2542–2556. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma S., Chan K.W., Lee T.K., Tang K.H., Wo J.Y., Zheng B.J., Guan X.Y. Aldehyde dehydrogenase discriminates the CD133 liver cancer stem cell populations. Mol. Cancer Res. 2008a;6:1146–1153. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma S., Lee T.K., Zheng B.J., Chan K.W., Guan X.Y. CD133+ HCC cancer stem cells confer chemoresistance by preferential expression of the Akt/PKB survival pathway. Oncogene. 2008b;27:1749–1758. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma S., Tang K.H., Chan Y.P., Lee T.K., Kwan P.S., Castilho A., Ng I., Man K., Wong N., To K.F., et al. miR-130b Promotes CD133(+) liver tumor-initiating cell growth and self-renewal via tumor protein 53-induced nuclear protein 1. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:694–707. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquardt J.U., Raggi C., Andersen J.B., Seo D., Avital I., Geller D., Lee Y.H., Kitade M., Holczbauer A., Gillen M.C., et al. Human hepatic cancer stem cells are characterized by common stemness traits and diverse oncogenic pathways. Hepatology. 2011;54:1031–1042. doi: 10.1002/hep.24454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Padura I., Marighetti P., Agliano A., Colombo F., Larzabal L., Redrado M., Bleau A.M., Prior C., Bertolini F., Calvo A. Residual dormant cancer stem-cell foci are responsible for tumor relapse after antiangiogenic metronomic therapy in hepatocellular carcinoma xenografts. Lab. Invest. 2012;92:952–966. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2012.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mima K., Okabe H., Ishimoto T., Hayashi H., Nakagawa S., Kuroki H., Watanabe M., Beppu T., Tamada M., Nagano O., et al. CD44s regulates the TGF-beta-mediated mesenchymal phenotype and is associated with poor prognosis in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2012;72:3414–3423. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokkapati S., Niopek K., Huang L., Cunniff K.J., Ruteshouser E.C., deCaestecker M., Finegold M.J., Huff V. Beta-catenin activation in a novel liver progenitor cell type is sufficient to cause hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatoblastoma. Cancer Res. 2014;74:4515–4525. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-3275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris S.M., Carter K.T., Baek J.Y., Koszarek A., Yeh M.M., Knoblaugh S.E., Grady W.M. TGF-beta signaling alters the pattern of liver tumorigenesis induced by Pten inactivation. Oncogene. 2014 doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.258. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuveut C., Wei Y., Buendia M.A. Mechanisms of HBV-related hepatocarcinogenesis. J. Hepatol. 2010;52:594–604. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nik-Zainal S., Van Loo P., Wedge D.C., Alexandrov L.B., Greenman C.D., Lau K.W., Raine K., Jones D., Marshall J., Ramakrishna M., et al. The life history of 21 breast cancers. Cell. 2012;149:994–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piao L.S., Hur W., Kim T.K., Hong S.W., Kim S.W., Choi J.E., Sung P.S., Song M.J., Lee B.C., Hwang D., et al. CD133+ liver cancer stem cells modulate radioresistance in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2012;315:129–137. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raggi C., Factor V.M., Seo D., Holczbauer A., Gillen M.C., Marquardt J.U., Andersen J.B., Durkin M., Thorgeirsson S.S. Epigenetic reprogramming modulates malignant properties of human liver cancer. Hepatology. 2014;59:2251–2262. doi: 10.1002/hep.27026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rountree C.B., Senadheera S., Mato J.M., Crooks G.M., Lu S.C. Expansion of liver cancer stem cells during aging in methionine adenosyltransferase 1A-deficient mice. Hepatology. 2008;47:1288–1297. doi: 10.1002/hep.22141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito T., Chiba T., Yuki K., Zen Y., Oshima M., Koide S., Motoyama T., Ogasawara S., Suzuki E., Ooka Y., et al. Metformin, a diabetes drug, eliminates tumor-initiating hepatocellular carcinoma cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e70010. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrader J., Gordon-Walker T.T., Aucott R.L., van Deemter M., Quaas A., Walsh S., Benten D., Forbes S.J., Wells R.G., Iredale J.P. Matrix stiffness modulates proliferation, chemotherapeutic response, and dormancy in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Hepatology. 2011;53:1192–1205. doi: 10.1002/hep.24108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan J., Shen J., Liu L., Xia F., Xu C., Duan G., Xu Y., Ma Q., Yang Z., Zhang Q., et al. Nanog regulates self-renewal of cancer stem cells through the insulin-like growth factor pathway in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2012;56:1004–1014. doi: 10.1002/hep.25745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y.J., Zhang S.S., Guo X.L., Sun K., Han Z.P., Li R., Zhao Q.D., Deng W.J., Xie X.Q., Zhang J.W., et al. Autophagy contributes to the survival of CD133+ liver cancer stem cells in the hypoxic and nutrient-deprived tumor microenvironment. Cancer Lett. 2013;339:70–81. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosa M.S., Bragado P., Aguirre-Ghiso J.A. Mechanisms of disseminated cancer cell dormancy: an awakening field. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2014;14:611–622. doi: 10.1038/nrc3793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z., Lu P., Gail M., Pee D., Zhang Q., Ming L., Wang J., Wu Y., Liu G., Zhu Y. Increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in male hepatitis B surface antigen carriers with chronic hepatitis who have detectable urinary aflatoxin metabolite M1. Hepatology. 1999;30:379–383. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J.C., Pan K., Chen M.S., Wang Q.J., Wang H., Ma H.Q., Li Y.Q., Liang X.T., Li J.J., Zhao J.J., et al. Dendritic cells-mediated CTLs targeting hepatocellular carcinoma stem cells. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2010;10:368–375. doi: 10.4161/cbt.10.4.12440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y.F., Xu Y., Yang X.R., Guo W., Zhang X., Qiu S.J., Shi R.Y., Hu B., Zhou J., Fan J. Circulating stem cell-like epithelial cell adhesion molecule-positive tumor cells indicate poor prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma after curative resection. Hepatology. 2013;57:1458–1468. doi: 10.1002/hep.26151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang H., Delgermaa L., Huang F., Oishi N., Liu L., He F., Zhao L., Murakami S. The transcriptional transactivation function of HBx protein is important for its augmentation role in hepatitis B virus replication. J. Virol. 2005;79:5548–5556. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.9.5548-5556.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang K.H., Ma S., Lee T.K., Chan Y.P., Kwan P.S., Tong C.M., Ng I.O., Man K., To K.F., Lai P.B., et al. CD133(+) liver tumor-initiating cells promote tumor angiogenesis, growth, and self-renewal through neurotensin/interleukin-8/CXCL1 signaling. Hepatology. 2012;55:807–820. doi: 10.1002/hep.24739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschaharganeh D.F., Xue W., Calvisi D.F., Evert M., Michurina T.V., Dow L.E., Banito A., Katz S.F., Kastenhuber E.R., Weissmueller S., et al. p53-dependent nestin regulation links tumor suppression to cellular plasticity in liver cancer. Cell. 2014;158:579–592. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan S., Zhao E., Kryczek I., Vatan L., Sadovskaya A., Ludema G., Simeone D.M., Zou W., Welling T.H. Tumor-associated macrophages produce interleukin 6 and signal via STAT3 to promote expansion of human hepatocellular carcinoma stem cells. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:1393–1404. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.08.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.Q., Ongkeko W.M., Chen L., Yang Z.F., Lu P., Chen K.K., Lopez J.P., Poon R.T., Fan S.T. Octamer 4 (Oct4) mediates chemotherapeutic drug resistance in liver cancer cells through a potential Oct4-AKT-ATP-binding cassette G2 pathway. Hepatology. 2010;52:528–539. doi: 10.1002/hep.23692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Yang W., Yan H.X., Luo T., Zhang J., Tang L., Wu F.Q., Zhang H.L., Yu L.X., Zheng L.Y., et al. Hepatitis B virus X (HBx) induces tumorigenicity of hepatic progenitor cells in 3,5-diethoxycarbonyl-1,4-dihydrocollidine-treated HBx transgenic mice. Hepatology. 2012;55:108–120. doi: 10.1002/hep.24675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.Q., Ng R.K., Ming X., Zhang W., Chen L., Chu A.C., Pang R., Lo C.M., Tsao S.W., Liu X., et al. Epigenetic regulation of pluripotent genes mediates stem cell features in human hepatocellular carcinoma and cancer cell lines. PLoS One. 2013;8:e72435. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu K., Ding J., Chen C., Sun W., Ning B.F., Wen W., Huang L., Han T., Yang W., Wang C., et al. Hepatic transforming growth factor beta gives rise to tumor-initiating cells and promotes liver cancer development. Hepatology. 2012;56:2255–2267. doi: 10.1002/hep.26007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurmbach E., Chen Y.B., Khitrov G., Zhang W., Roayaie S., Schwartz M., Fiel I., Thung S., Mazzaferro V., Bruix J., et al. Genome-wide molecular profiles of HCV-induced dysplasia and hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2007;45:938–947. doi: 10.1002/hep.21622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia H., Ooi L.L., Hui K.M. MicroRNA-216a/217-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition targets PTEN and SMAD7 to promote drug resistance and recurrence of liver cancer. Hepatology. 2013;58:629–641. doi: 10.1002/hep.26369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X., Xing B., Hu M., Xu Z., Xie Y., Dai G., Gu J., Wang Y., Zhang Z. Recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma cells with stem cell-like properties: possible targets for immunotherapy. Cytotherapy. 2010;12:190–200. doi: 10.3109/14653240903390803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita T., Ji J., Budhu A., Forgues M., Yang W., Wang H.Y., Jia H., Ye Q., Qin L.X., Wauthier E., et al. EpCAM-positive hepatocellular carcinoma cells are tumor-initiating cells with stem/progenitor cell features. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1012–1024. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z.F., Ho D.W., Ng M.N., Lau C.K., Yu W.C., Ngai P., Chu P.W., Lam C.T., Poon R.T., Fan S.T. Significance of CD90+ cancer stem cells in human liver cancer. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:153–166. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z., Zhang L., Ma A., Liu L., Li J., Gu J., Liu Y. Transient mTOR inhibition facilitates continuous growth of liver tumors by modulating the maintenance of CD133+ cell populations. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28405. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W., Wang C., Lin Y., Liu Q., Yu L.X., Tang L., Yan H.X., Fu J., Chen Y., Zhang H.L., et al. OV6(+) tumor-initiating cells contribute to tumor progression and invasion in human hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2012;57:613–620. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You H., Ding W., Rountree C.B. Epigenetic regulation of cancer stem cell marker CD133 by transforming growth factor-beta. Hepatology. 2010;51:1635–1644. doi: 10.1002/hep.23544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Sun H., Zhao F., Lu P., Ge C., Li H., Hou H., Yan M., Chen T., Jiang G., et al. BMP4 administration induces differentiation of CD133+ hepatic cancer stem cells, blocking their contributions to hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2012;72:4276–4285. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Li H., Ge C., Li M., Zhao F.Y., Hou H.L., Zhu M.X., Tian H., Zhang L.X., Chen T.Y., et al. Inhibitory effects of transcription factor Ikaros on the expression of liver cancer stem cell marker CD133 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2014;15:10621–10635. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W., Wang L., Han H., Jin K., Lin N., Guo T., Chen Y., Cheng H., Lu F., Fang W., et al. 1B50-1, a mAb raised against recurrent tumor cells, targets liver tumor-initiating cells by binding to the calcium channel α2δ1 subunit. Cancer Cell. 2013;23:541–556. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]