Abstract

NMDA glutamate receptors (NMDARs) have critical functional roles in the nervous system but NMDAR over-activity can contribute to neuronal damage. The open channel NMDAR blocker, memantine is used to treat certain neurodegenerative diseases, including Parkinson’s disease (PD) and is well tolerated clinically. We have investigated memantine block of NMDARs in substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) dopamine neurones, which show severe pathology in PD. Memantine (10 μM) caused robust inhibition of whole-cell (synaptic and extrasynaptic) NMDARs activated by NMDA at a high concentration or a long duration, low concentration. Less memantine block of NMDAR-EPSCs was seen in response to low frequency synaptic stimulation, while responses to high frequency synaptic stimulation were robustly inhibited by memantine; thus memantine inhibition of NMDAR-EPSCs showed frequency-dependence. By contrast, MK-801 (10 μM) inhibition of NMDAR-EPSCs was not significantly different at low versus high frequencies of synaptic stimulation. Using immunohistochemistry, confocal imaging and stereological analysis, NMDA was found to reduce the density of cells expressing tyrosine hydroxylase, a marker of viable dopamine neurones; memantine prevented the NMDA-evoked decrease. In conclusion, memantine blocked NMDAR populations in different subcellular locations in SNc dopamine neurones but the degree of block depended on the intensity of agonist presentation at the NMDAR. This profile may contribute to the beneficial effects of memantine in PD, as glutamatergic activity is reported to increase, and memantine could preferentially reduce over-activity while leaving some physiological signalling intact.

Keywords: Excitotoxicity, Use-dependent antagonist

1. Introduction

NMDA glutamate receptors (NMDARs) play a critical role in neuronal development, physiology and plasticity. Over-activity of NMDARs may contribute to neuronal damage in neurological disorders including stroke, epilepsy and neurodegeneration (Kemp and McKernan, 2002; Lau and Zukin, 2007; Hardingham and Bading, 2010). The use of NMDA glutamate receptor antagonists to limit NMDAR activity has been considered as a potential therapy in Parkinson’s Disease (PD) (Doble, 1999; Blandini et al., 2000; Hallett and Standaert, 2004). However, progress with this approach has been stifled due to undesirable side effects such as psychosis and cytotoxicity that are associated with NMDAR blockade (Krystal et al., 1994; De Vry and Jentzsch, 2003; Low and Roland, 2004; Pomarol-Clotet et al., 2006; Hardingham and Bading, 2010). This is in large part due to the ubiquitous expression and essential function of NMDARs throughout the brain. Thus, there is a need for therapeutics to provide neuroprotection but preserve normal function.

Use-dependent NMDAR open channel blockers have the potential to correct pathological NMDAR signalling and prevent excitotoxic NMDAR induced neuronal loss (Danysz et al., 1997). The potent use-dependent channel blocker, MK-801 (MacDonald et al., 1991), is effective in reducing excitotoxicity, most likely due to the slow rate of dissociation from the binding site in the NMDAR channel (reviewed by Lipton, 2006). However, it causes adverse effects in patients including drowsiness and potentially coma. By contrast, the use-dependent blocker memantine is used to treat neurodegenerative diseases including PD and is well tolerated clinically (Rabey et al., 1992; Puzin et al., 2007; Litvinenko et al., 2010; Chen and Lipton, 2006; Lipton, 2007). The mechanism underlying its clinical tolerability is currently under debate. Possibly memantine corrects abnormal NMDAR activity and offers neuroprotection against excitotoxic insults, whilst leaving physiological signalling intact (Lipton, 2004; Johnson and Kotermanski, 2006; Chen and Lipton, 2006; Parsons et al., 2007), most likely due to it’s use-dependence and relatively fast rate of dissociation from the NMDAR channel (Lipton, 2006). Recent studies have suggested that memantine preferentially blocks extrasynaptic receptors in hippocampal neurones, with minimal synaptic inhibition (Xia et al., 2010). This idea fits well when considering the extrasynaptic NMDAR hypothesis, which is based on the notion that neurotoxicity is initiated by extrasynaptic NMDARs, while synaptic NMDAR activity is neuroprotective (Hardingham and Bading, 2010). However, a recent study demonstrated that memantine can also robustly block synaptic signalling in cultured hippocampal neurones during hypoxic insult (Wroge et al., 2012).

In PD a severe pathology is the loss of functional dopaminergic neurones in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc), but memantine block of NMDARs in SNc dopamine neurones has not been investigated. Here we report that memantine, at a clinically relevant concentration, blocked both synaptic and whole-cell (synaptic and extrasynaptic) NMDARs. This effect depended on agonist presentation at the NMDAR. Furthermore, NMDAR activation by NMDA reduced the density of dopamine neurones in the SNc and memantine reversed this effect, suggesting that memantine has neuroprotective potential in PD.

2. Methods

2.1. Slice preparation

Male Wistar rats aged 3–4 weeks were decapitated under isoflurane anaesthesia in accordance with the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act UK (1986) and Local Ethical Committee approval. The brain was removed into ice cold slicing solution composed of (mM): NaCl 75; sucrose 100; glucose 25; NaHCO3 25; KCl 2.5; CaCl2 1; MgCl2 4; NaH2PO4 1.25; kynurenic acid 0.25, maintained at pH 7.4 by bubbling with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. Horizontal midbrain slices (250 μm) containing the substantia nigra were prepared using a Campden 7000smz Vibrating Microtome (Campden Instruments UK). Slices were transferred to a submersion incubation chamber containing a modified recording solution of composition (mM): NaCl 125; glucose 25; KCl 2.5; NaHCO3 26; NaH2PO4 1.26, MgCl2 4; CaCl2 1, bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 and maintained at 30 °C for 1–6 h prior to use. Slices were transferred to the stage of an Olympus BX51W upright microscope and SNc dopamine neurones were viewed at a magnification of ×600 using differential interference contrast optics. The chamber was perfused at ~2 ml/min with oxygenated recording solution at 30 ± 2 °C (as above but with 10 mM glucose, 0.1 mM MgCl2; the latter was used because the amplitude of NMDAR responses at −50 mV are very small in physiological [Mg2+]). Patch pipettes were pulled from thin walled borosilicate glass (GC150F, Harvard apparatus, Kent, UK) to a resistance of ~1–2 MΩ when filled with pipette solution containing (mM): CsCH3SO3 130; CsCl 5; NaCl 2.8; HEPES 20; EGTA 5; CaCl2 0.5; MgCl2 3; Mg-ATP 2; Na-GTP 0.3; pH ~7.2.

2.2. Electrophysiology

Cells were voltage-clamped at −50 mV using an Axopatch 200B patch-clamp amplifier (Axon Instruments, USA), and the membrane current low pass filtered at 2 kHz and sampled at 20 kHz using a Micro 1401 controlled by Spike 2 (Version 4) software (Cambridge Electronic Design, Cambridge, UK). Series resistance (typically 4–6 MΩ) was compensated by 40%. Whole-cell NMDAR currents were evoked by agonist applications (NMDA concentration as specified in text; glycine 10 μM) in the presence of TTX (100 nM; Tocris Bioscience UK) and picrotoxin (50 μM; Sigma–Aldrich UK). Drug applications were either via the bath perfusion system, or via a Picospritzer (Intracel, UK) (1 s, 15 psi) at 200 s intervals. Synaptic currents were evoked using a bipolar stainless steel electrode (Frederick Haer and Co., USA) placed within the SN rostral to the recorded cell at an approximate distance of 0.5 mm; stimuli (200 μs duration; stimulation intensity, 100–400 μA) were applied at frequencies specified in the text in the presence of DNQX (10 μM), picrotoxin (50 μM) and glycine (10 μM) (all from Sigma–Aldrich UK).

SNc dopamine neurones were identified by their anatomical location, somatic morphology and the presence of a prominent inward current (Isag) during a voltage step from −60 to −110 mV. This current is representative of a hyperpolarisation-activated inward (Ih) current mediated by hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated (HCN) channels in SNc dopamine neurones (Washio et al., 1999; Neuhoff et al., 2002; Margolis et al., 2006). Approximately 90% of SNc neurones are dopaminergic (Fallon and Loughlin, 1995).

2.3. Experimental protocols and data analysis

To quantify inhibition of whole-cell NMDAR currents, repeated agonist applications were first made with a picospritzer at 200 s intervals in control solution and during bath perfusion with memantine (10 μM; Tocris Bioscience UK). Percentage inhibition was calculated by comparing the average of three control NMDAR peak current amplitudes with the peak current amplitude of the sixth response to NMDA after perfusion with memantine.

Inhibition of NMDA currents induced by prolonged agonist application was calculated by first applying NMDA (10 μM) for at least 5 min to evoke steady state whole-cell NMDAR responses and then applying memantine (10 μM) along with NMDA for at least a further 8 min; the peak NMDA current 20 s prior to memantine application and the peak NMDA current in the presence of memantine (20 s) were measured using cursors in the Spike 2 software.

To quantify inhibition of synaptic NMDARs, NMDAR-EPSC amplitudes in response to synaptic stimulation at 0.1 Hz were measured using cursors in Spike 2, normalised to pre-antagonist control amplitudes and then the average of control NMDAR-EPSCs five minutes before and the average of responses 13–17 min after application of memantine or (+)-MK-801 (Sigma–Aldrich UK) were used to calculate the percentage inhibition. Summated NMDAR-EPSC amplitudes in response to higher frequencies of stimulation (20 Hz or 80 Hz) were measured using cursors in Spike 2 and then the peak of summated NMDAR-EPSCs from the average of three control responses prior to and five responses 13 to 17 min after antagonist application were used to calculate the percentage inhibition. The total charge transfer during NMDAR-EPSCs in response to different frequencies of synaptic stimulation was calculated as the integral of the current during the final pre-antagonist control summated NMDAR-EPSC using the following equation:

where Q is the total charge transfer (pC), I is the current amplitude (pA) of each data point sampled in the EPSC and t is the time between sampling (0.00005 s for a sampling frequency of 20 kHz). The weighted time constant of the deactivation of NMDA-EPSCs in response to different frequencies of stimulation was calculated from a fit of two exponentials (weighted to the amplitude of each exponent) to the peak-to-baseline decay of pre-antagonist NMDA-EPSCs (an average of 200 s/20 EPSCs for 0.1 Hz or 300 s/5 EPSCs for 20 Hz and 80 Hz).

2.4. Immunofluorescence and stereological analysis

Four horizontal midbrain slices (500 μm) containing the entire substantia nigra were prepared as above and immediately transferred to an incubation chamber containing modified recording solution of composition (mM): NaCl 125; glucose 25; KCl 2.5; NaHCO3 26; NaH2PO4 1.26, MgCl2 4; CaCl2 1, bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 and maintained at 30 °C for 1 h prior to treatment incubation. To avoid complications that may arise from hemispheric differences in SNc volume, only slices from the left hemisphere were used. Brain slices were next transferred to the solution described above (but with 0.1 mM MgCl2) with one of four additional treatments: ‘Control’ (glycine 10 μM, picrotoxin 50 μM), ‘NMDA 1 mM’ (as control plus 1 mM NMDA; Sigma-Aldrich UK), ‘Memantine 10 μM’ (as control plus 10 μM memantine) and ‘NMDA 1 mM memantine 10 μM’ (as NMDA 1 mM plus 10 μM memantine). After 1 h, slices were transferred to fixative (4% formaldehyde in HEPES buffer) and left overnight. Slices were trimmed to isolate the midbrain and re-sectioned to a thickness of 100 μm in 0.1 M HEPES buffer (pH 7.4) using a VT1000 Vibroslicer (Leica, Germany), before being transferred to blocking buffer (1% Fish gelatine) in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) with 20 μM TRIS and 20 μM TWEEN (pH 7.6) and left overnight at 4 °C. Slices were then incubated in blocking buffer containing mouse anti-tyrosine hydroxylase antibody (Millipore; 1:250) for 24 h, washed in PBS, then incubated in blocking buffer containing donkey anti-mouse antibody (conjugated to Alexa Fluor 568; Invitrogen; 1:200) and Hoescht (1:200) for 1 h. Slices were again washed in PBS then mounted on microscope slides with ProLong Gold antifade reagent for imaging using a confocal microscope (DMIRE2, Leica, Germany).

Stereological estimates of SNc volume were calculated using the Cavalieri method. Low power images ( ×50) were taken of each tyrosine hydroxylase labelled (TH+) slice throughout the entire hemi-SNc in a ventral to dorsal sequence; only hemi-brains with a complete set of SNc-containing slices were used for volume analysis (n = 41). To calculate the area of SNc in each slice, a two dimensional grid was superimposed randomly over each image with crosses at a distance of 40 μm apart. The volume associated with each grid point was then calculated from the area associated with each grid point and the thickness of the slice. From this, the total volume of SNc was calculated by summing the number of grid points that fell within the SNc border for each slice, and multiplying by the volume.

The absolute neuronal density was estimated using the optical dissector principle. Two images were taken a known distance (7 μm) apart from a full set of high power ( ×630) image stacks from randomly selected slices, creating a known sampling (dissector) volume within which neurones were counted. The density of TH+ cells within each SNc was estimated from 2 to 4 dissector volumes from each hemi-SNc. The total number of neurones counted in all dissector volumes per hemi-SNc was used to calculate the density of TH+ neurones per mm3 and then, using the mean volume of SNc calculated from all hemi-SNc (n = 41) using the Cavalieri method, this was converted to the density of TH+ neurones per hemi-SNc.

2.5. Statistics

Data are expressed as mean ± standard error (SE); the ‘n’ values refer to the number of cells (which also corresponds to the number of slices). For comparisons of two groups of data, the Student’s t-test was used. For three or more groups of data, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-tests were used. For correlation analysis, Pearson’s test was used. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 4.

3. Results

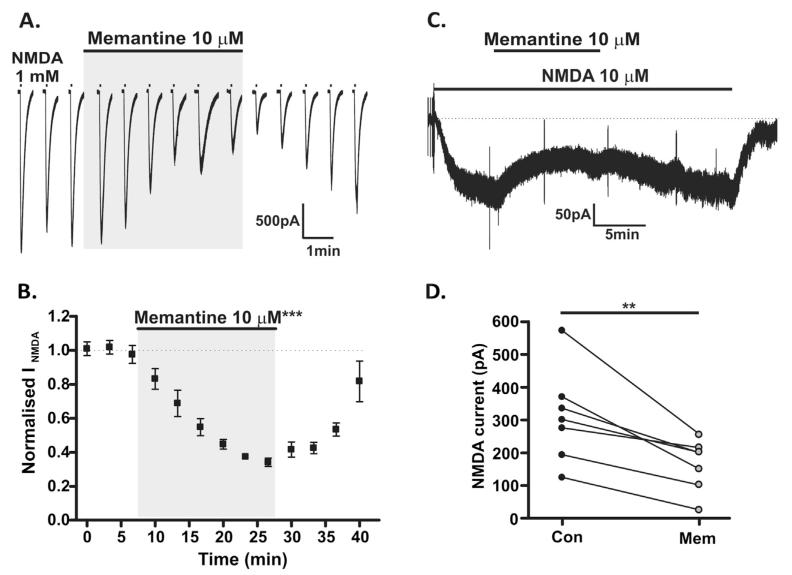

It is estimated that the concentration of memantine at NMDARs following administration of a clinical dose of memantine is in the range of 1–10 μM (Hesselink et al., 1999; Danysz et al., 2000) and so a concentration of 10 μM was used in the following experiments. In the first set of experiments, in order to activate whole-cell (i.e. both synaptic and extrasynaptic) NMDARs, NMDA was applied via a picospritzer (1 mM; 1 s, at 200 s intervals; in the presence of 10 μM glycine and 50 μM picrotoxin) to SNc dopamine neurones voltage-clamped to −50 mV. Mean NMDAR responses were −2184.9 ± 112.7 pA; these responses were stable over 3–4 applications (Fig. 1A). Bath perfusion of memantine (10 μM) caused a reversible inhibition of whole-cell NMDAR responses (65.9 ± 2.5%, n = 6; P < 0.001, paired t-test; Fig. 1A and B).

Fig. 1.

Use-dependent block of whole-cell (extrasynaptic and synaptic) NMDARs. (A) Representative recording from SNc dopamine neurone at −50 mV, demonstrating responses to picospritzer applications of 1 mM NMDA (plus 10 μM glycine, in 50 μM picrotoxin and 0.1 mM Mg2+) at 200 s intervals and inhibition of these responses by bath applied 10 μM memantine. Scale bar refers to current traces, intervening time periods are not shown in full. (B) Amplitudes of responses from 6 picospritzer experiments, NMDAR responses are normalised to three control responses; % inhibition with 10 μM memantine was measured at 26 min (65.9 ± 2.5%, ***P < 0.001, paired t-test). (C) Example recording from SNc dopamine neurone at −50 mV, demonstrating the response to prolonged bath application of 10 μM NMDA (plus 10 μM glycine, in 50 μM picrotoxin and 0.1 mM Mg2+) and inhibition of this response by bath applied memantine (10 μM). Brief transients indicate test pulses to check the stability of the series resistance. (D) Amplitudes of responses to bath applied NMDA (10 μM) before (Con) and after (Mem) application of 10 μM memantine (47.9 ± 7.2% inhibition, n = 7; **P < 0.01, paired t-test).

In a subsequent set of experiments, a low but continuous bath application of agonist (NMDA 10 μM) was investigated. NMDAR responses were −310.0 ± 54.0 pA (n = 7) and long duration (Fig. 1C). Bath of application of memantine (10 μM) caused a reversible inhibition of the response (47.9 ± 7.2%, n = 7; P < 0.01, paired t-test; Fig. 1C and D). Thus memantine, at a clinically relevant concentration, robustly inhibits whole-cell (synaptic and extra-synaptic) NMDAR currents in response to applications of a high agonist concentration and in response to prolonged application of a low agonist concentration.

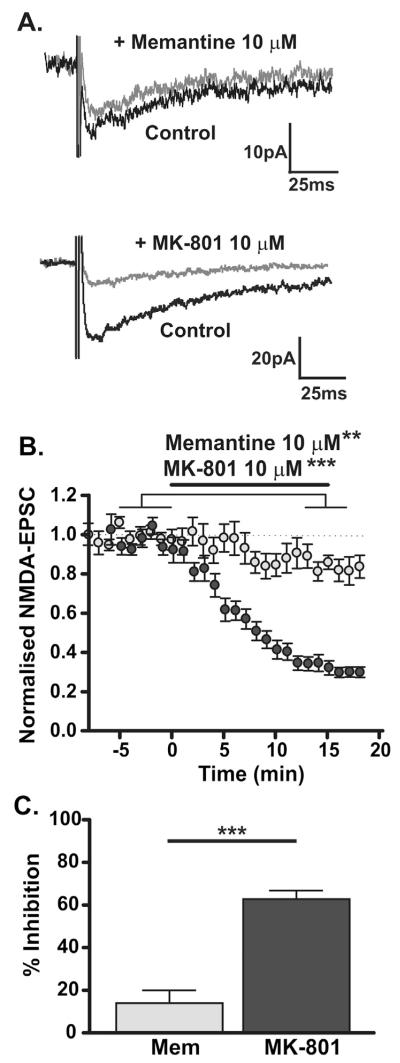

NMDAR antagonists will only be useful therapeutic agents if the side effect profile is limited and to achieve this minimal inhibition of physiological NMDAR activity is critical. Memantine block of synaptic NMDAR responses (in the presence of 10 μM DNQX, 10 μM glycine and 50 μM picrotoxin) was therefore assessed. NMDAR-EPSCs in response to electrical stimulation (200 μs; 0.1 Hz) had an average amplitude of −35.0 ± 1.6 pA and a weighted decay time constant of 210 ± 32 ms (Table 1). Memantine (10 μM) had a small but significant effect on NMDAR-EPSCs (P < 0.01, paired t-test); mean inhibition was 13.9 ± 6.0% (n = 8, Fig. 2A–C). By contrast, MK-801 (10 μM; equivalent concentrations of MK-801 and memantine were used to highlight the extent to which k–off determines the degree of open channel block) caused substantial inhibition of NMDA-EPSCs in response to 0.1 Hz synaptic stimulation (62.8 ± 4.0%, n = 7; P < 0.001, paired t-test; Fig. 2A–C), significantly more than memantine (P < 0.001, unpaired t-test). Thus, memantine left low frequency synaptic NMDAR activity relatively intact, while MK-801 caused substantial block.

Table 1.

Synaptic stimulation parameters and properties of resultant NMDAR-EPSCs.

| Stimulus |

NMDAR response |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Duration | Number | Amplitude (pA) | τw (ms) | Charge transfer (pC) |

| 0.1 Hz (n = 8) | 1 | −35.0 ± 1.6* | 210.1 ± 32.0 | 2.8 ± 0.4 | |

| 20 Hz (n = 6) | 200 ms | 4 | −60.9 ± 11.0* | 199.9 ± 54.7 | 10.2 ± 1.0 |

| 20 Hz (n = 7) | 800 ms | 16 | −64.1 ± 8.4* | 196.4 ± 11.4 | 38.9 ± 5.3 |

| 80 Hz (n = 7) | 200 ms | 16 | −218.4 ± 31.6 | 178.6 ± 13.1 | 64.7 ± 6.4 |

Amplitude:

All P < 0.001 versus 80 Hz. Weighted decay time constant: All not significantly different. Charge transfer: 0.1 Hz and 20 Hz/200 ms, P < 0.001 compared with 80 Hz and with 20 Hz/800 ms; 0.1 Hz versus 20 Hz/200 ms, not significantly different. 80 Hz versus 20 Hz/800 ms, P < 0.01. ANOVA with posthoc Bonferroni Multiple Comparisons test.

Fig. 2.

Use-dependent block of low frequency synaptic NMDAR-EPSCs. (A) Top: Example traces of NMDA-EPSCs (average of 20 events) evoked by 0.1 Hz synaptic stimulation in control (black traces, recorded at −50 mV in 10 μM DNQX, 10 μM glycine, 50 μM picrotoxin and 0.1 mM Mg2+) and in the presence of memantine (10 μM; grey traces). Bottom: Example traces of NMDA-EPSCs evoked by 0.1 Hz synaptic stimulation in control (black traces, as above) and in the presence of MK-801 (10 μM; grey traces). (B) Time course of memantine (light grey symbols; n = 8; **P < 0.01) or MK-801 (dark grey symbols; n = 7; ***P < 0.001) inhibition of NMDAR-EPSCs evoked at 0.1 Hz. (C) Inhibition of NMDAR-EPSCs evoked by 0.1 Hz stimulation by memantine (13.9 ± 6%, n = 8) and by MK-801 (62.8 ± 4%, n = 7; P < 0.0001, unpaired t-test).

The mean amplitude of synaptic responses was considerably less than the mean amplitudes of whole-cell responses and so the different inhibitory effect of memantine might reflect the intensity of NMDAR activation. In order to determine whether memantine block of larger amplitude and/or longer duration synaptic NMDAR responses would be greater, NMDAR-EPSCs were recorded in response to bursts of synaptic stimulation at either 20 Hz or 80 Hz (given every 60 s). These synaptic burst stimulation paradigms induced summated NMDAR-EPSCs of different amplitude and charge transfer, although the decay time constants were not significantly different for any synaptic stimulation paradigm used (Table 1).

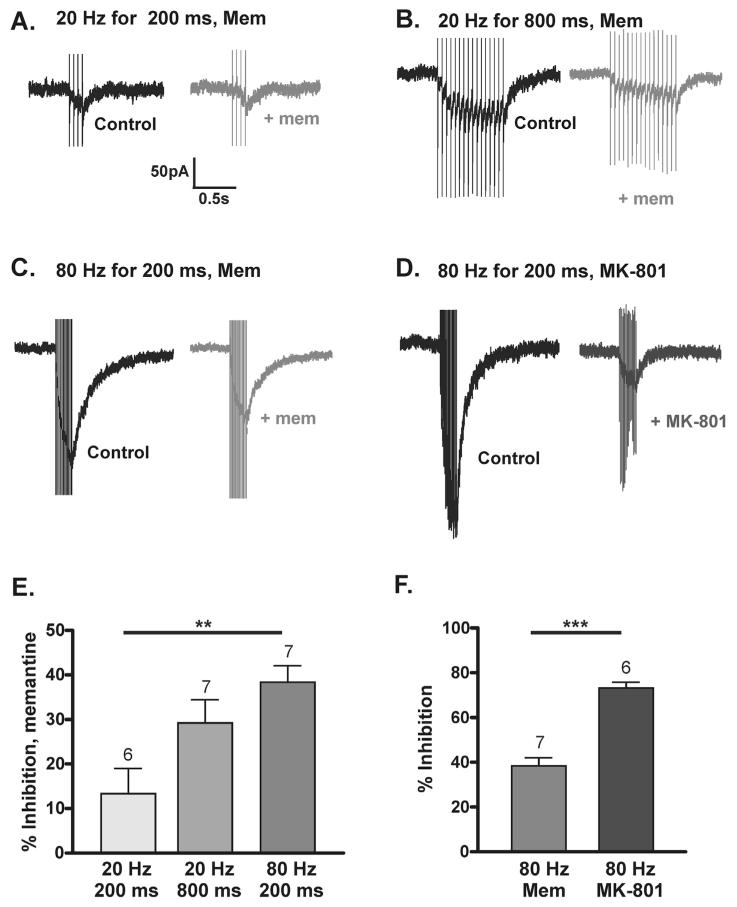

Stimulation at 20 Hz for 200 ms resulted in NMDAR-EPSCs with a small amplitude (example in Fig. 3A; Table 1); memantine inhibition was 12.4 ± 6.2% (n = 6; Fig. 3A and E). Stimulation at a higher frequency (80 Hz) for 200 ms evoked NMDAR-EPSCs with significantly larger amplitudes than responses to 20 Hz/200 ms stimulation (example in Fig. 3C and D; Table 1). Memantine inhibition of responses to 80 Hz stimulation was 38.6 ± 3.2% (n = 7, Fig. 3C and E), significantly more inhibition than that seen with 20 Hz/200 ms (P < 0.01; ANOVA with Bonferroni Multiple Comparison’s test). Stimulation at 20 Hz for 800 ms resulted in NMDAR-EPSCs with similar amplitudes to those evoked at 20 Hz/200 ms and smaller amplitudes than those evoked by 80 Hz stimulation (example in Fig. 3B; Table 1). Charge transfer was intermediate of that for 20 Hz/200 ms and 80 Hz/200 ms stimulation. Memantine inhibition of responses to 20 Hz/800 ms was 29.5 ± 4.7% (n = 7, Fig. 3B and E; P > 0.05 comapred with 20 Hz/200 ms or 80 Hz/200 ms, ANOVA with Bonferroni Multiple Comparison’s test).

Fig. 3.

Frequency-dependent memantine block of NMDAR-EPSCs. (A–D) NMDAR-EPSCs evoked by synaptic stimulation at −50 mV. Black traces are control and grey traces are in memantine or MK-801 as indicated. Scale bar applies to (A) 20 Hz/200 ms + memantine (B) 20 Hz/800 ms + memantine (C) 80 Hz/200 ms + memantine and (D) 80 Hz/200 ms + MK-801. (E) Graph of % inhibition with memantine in response to stimulation at 20 Hz/200 ms (12.4 ± 6.2%, n = 6), 20 Hz/800 ms (29.5 ± 4.7%, n = 7) and 80 Hz/200 ms (38.6 ± 3.2%, n = 7); **P < 0.01, ANOVA with Bonferroni Multiple Comparison’s test. (F) Graph of % inhibition of NMDAR-EPSCs in response to 80 Hz stimulation by memantine (n = 7) or by MK-801 (73.2 ± 2.6%, n = 6; ***P < 0.001, unpaired t-test).

Significantly more inhibition of NMDAR-EPSCs in response to 80 Hz stimulation was observed with MK-801 (73.2 ± 2.6%, n = 6) than with memantine (P < 0.001, unpaired t-test). Unlike memantine block, the degree of inhibition seen with MK-801 was not frequency-dependent, as there was no significant difference in the percent inhibition of NMDAR-EPSCs evoked at 80 Hz compared with 0.1 Hz synaptic stimulation (P = 0.055). This suggests that at 0.1 Hz and 80 Hz stimulation there is no significant MK-801 unblock between each stimulus.

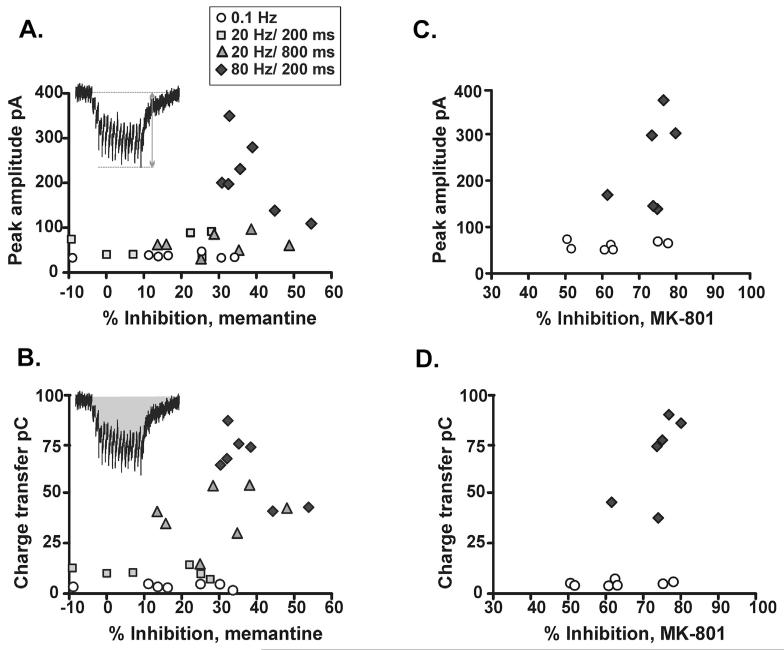

To gain insight into the properties of NMDAR-EPSCs that determine the degree of memantine block, the NMDAR-EPSC amplitude and charge transfer of control responses to 0.1 Hz, 20 Hz and 80 Hz were plotted against percent inhibition of the peak EPSC amplitudes. As might be expected for open channel blockers (if the NMDAR saturation varies at different synapses; Higley et al., 2009; Lisman et al., 2007), there was a significant positive correlation between the amplitude of control responses and the degree of memantine inhibition (Fig. 4A; P = 0.03) and between total charge transfer during control responses and memantine inhibition (Fig. 4B; P = 0.002). There was also a significant positive correlation between the degree of inhibition with MK-801 and control amplitudes (P = 0.049) and charge transfer (P = 0.03) (Fig. 4C and D), although the correlation is less obvious because of the robust inhibition at both frequencies tested with MK-801. These results suggest that the product of amplitude and duration of receptor activation is an important determinant of the extent of memantine block of NMDAR-EPSCs.

Fig. 4.

Block of synaptic NMDARs depends on the intensity of agonist presentation. (A) Plot of percent inhibition of peak NMDAR-EPSC amplitude by memantine versus peak amplitude of pre-memantine control NMDAR-EPSCs (significant correlation, P = 0.03, Pearson’s test). Inset indicates measurement of peak NMDAR-EPSC amplitude in response to burst stimuli (in this example, 20 Hz/800 ms; stimulus artefacts have been removed). (B) As in A, but inhibition is plotted versus charge transfer during summated control NMDAR-EPSCs (P = 0.002). Inset: shaded area indicates measurement of charge transfer in response to burst stimuli (in this example, 20 Hz/800 ms; stimulus artefacts have been removed). (C–D) as for (A–B), but plot is percent inhibition with MK-801 plotted against amplitude (P = 0.049) and charge transfer (P = 0.03) of control responses in those experiments.

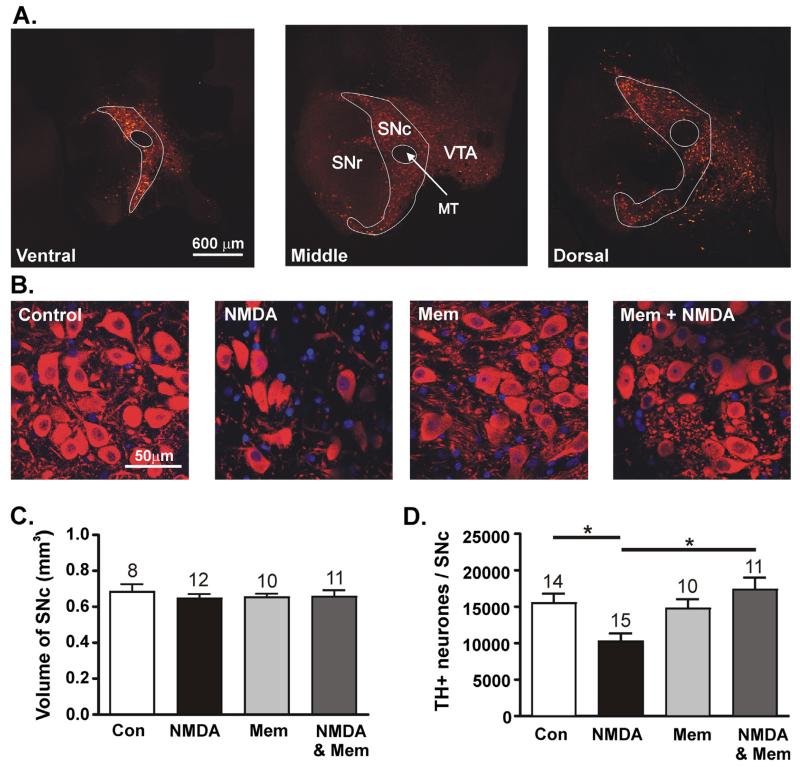

Excitotoxicity is a putative contributing factor in the decline in dopamine cell function in PD, therefore NMDAR antagonists have neuroprotective potential (Doble, 1999). Having shown that memantine is able to block persistently activated NMDARs in SNc dopamine neurones, the following experiments were designed to assess whether persistent exposure to NMDA can reduce the density of dopamine neurones, and whether memantine can prevent this effect. To do this, measurements were made of the total SNc volume and dopamine neurone density in four treatment groups: ‘Control’; ‘NMDA 1 mM’; ‘Memantine 10 μM’ and ‘Memantine 10 μM + NMDA 1 mM’. Images of anti-tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) antibody labelled neurones taken throughout the entire hemi-SNc were used to calculate hemi-SNc volume; example TH+ immunolabelling in three single planes of SNc from one rat is shown in Fig. 5A. The total volume was not significantly different in any treatment group (Fig. 5C; P = 0.87, ANOVA). The density of TH+ neurones per hemi-SNc was assessed by normalising TH+ neurone density per unit area (example images shown in Fig. 5B) to the mean hemi-SNc volume. In the control group the average density of TH+ neurones was 15,482 ± 1307 neurones/hemi-SNc (n = 14). Incubation with NMDA (1 mM, 1 h) resulted in a significantly lower density of neurones expressing TH (10,238 ± 1111 neurones/hemi-SNc; n = 15; P < 0.05, ANOVA with Bonferroni Multiple Comparison’s test). Incubation with memantine (10 μM, 1 h) alone had no significant effect on the density of TH expressing neurones (14,731 ± 1290 neurones/hemi-SNc; n = 10; P < 0.05, ANOVA with Bonferroni Multiple Comparison’s test) when compared with control. Co-incubation of slices with NMDA 1 mM and memantine 10 μM resulted in a density of TH+ neurones that was significantly different from NMDA 1 mM alone (17,334 ± 1675 neurones/hemi-SNc; n = 11; P < 0.05, ANOVA with Bonferroni Multiple Comparison’s test), but not from control (P > 0.05, ANOVA with Bonferroni Multiple Comparison’s test). Thus, incubation with NMDA reduced the density of TH expressing neurones, and this reduction was prevented by co-incubation with memantine. These data are shown in Fig. 5D.

Fig. 5.

Memantine prevents NMDA-evoked decrease in the density of TH+ cells in SNc. (A) Low power images of immunolabelled TH+ neurones taken from three planes in ventral (left), middle and dorsal (right) locations of one hemi-SNc. TH+ neurones are coloured in red. The boundary of SNc is outlined in white. Other regions indicated are the substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNr), dopaminergic neurones of the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and the medial terminal nucleus of the accessory optic tract (MT). (B) High power images of TH+ neurones (red) and Hoescht-labelled nuclei (blue) in control, NMDA, memantine and NMDA + memantine. (C) Graph of total volume per hemi-SNc after a one hour incubation in either control solution (n = 8), 1 mM NMDA alone (n = 12), 10 μM memantine alone (n = 10) or 1 mM NMDA + 10 μM memantine (n = 11). (C) Graph of TH+ neurone density per hemi-SNc, normalised to the mean SNc volume in either control solution (n = 14), 1 mM NMDA alone (n = 15), 10 μM memantine alone (n = 10) or 1 mM NMDA + 10 μM memantine (n = 11). (*P < 0.05, ANOVA with Bonferroni Multiple Comparison’s test).

4. Discussion

The NMDAR channel blocker, memantine is used in the treatment of neurodegenerative disorders including PD (Rabey et al., 1992; Puzin et al., 2007; Lipton, 2007; Litvinenko et al., 2010). However, the precise mechanism of action by which memantine achieves clinical benefit, whereas other channel blockers such as MK-801 do not, is still the subject of debate (Lipton, 2004, 2007; Johnson and Kotermanski, 2006; Chen and Lipton, 2006; Parsons et al., 2007). The key elements of the memantine-NMDAR interaction that most likely contribute to clinical utility are a relatively low affinity and fast unblock. One hypothesis is that, through these interactions, memantine is able to selectively target extrasynaptic NMDARs (Xia et al., 2010). Alternatively, the dynamic of agonist presentation at the receptor may be critical in determining the degree of memantine block (Wroge et al., 2012). In the present study, memantine block was investigated in SNc dopamine neurones while activating NMDARs using different modes of agonist exposure. Whole-cell NMDARs were robustly blocked by memantine, while synaptic NMDARs were blocked in a frequency-dependent manner by memantine, but were substantially blocked by MK-801 at both low and high frequency stimulation.

4.1. Inhibition of whole-cell NMDA responses

Whole-cell application of a high concentration of NMDA induced large amplitude responses that were robustly inhibited by memantine, consistent with memantine being an open channel blocker, i.e. the extent of block is directly related to the receptor open probability (Popen). Prolonged application of a low concentration of NMDA evoked small amplitude responses that were also robustly inhibited by memantine. Although Popen may be lower in low concentrations of agonist, the prolonged presence of agonist at the receptor will allow equilibrium block to be achieved (Gilling et al., 2007; Parsons et al., 2007). Furthermore, due to the partial ‘trapping block’ properties of memantine action, the time course of recovery from block by memantine will be slower with a lower concentration of agonist (Chen and Lipton,1997; Gilling et al., 2007). These experiments highlight the ability of memantine to substantially block whole-cell responses when agonist presentation at the receptor is either at high concentration or at a prolonged low concentration.

Both synaptic and extrasynaptic NMDARs of SNc dopamine neurones are likely to be composed of a mixture of GluN2B and GluN2D subunits (Jones and Gibb, 2005; Brothwell et al., 2008; Suárez et al., 2010). Investigations of the mechanism of action of memantine have focused on the GluN1/GluN2A and GluN1/GluN2B receptor subtypes (Kashiwagi et al., 2002; Chen and Lipton, 2006) as these are the most prominent receptors in the adult cerebral cortex and hippocampus (Cull-Candy and Leszkiewicz, 2004).Kotermanski and Johnson (2009) and Otton et al. (2011) have shown that near the resting membrane potential, in the presence of physiological Mg2+ concentrations, the potency of memantine at GluN2A and GluN2B-type receptors is reduced (from 5 to 20-fold) while for GluN2C and GluN2D-type receptors the decrease is only about 3-fold (Kotermanski and Johnson, 2009). As a result, in vivo therapeutic memantine concentrations may preferentially target neurones expressing GluN2C and GluN2D-containing NMDARs at synaptic sites, such as SNc dopamine neurones (Brothwell et al., 2008). In this study, [Mg2+] was lowered to 0.1 mM to minimise the block of NMDARs at the holding potential of −50 mV, and therefore little selectivity of memantine for GluN2B versus GluN2D would be expected.

4.2. Inhibition of synaptic NMDARs

Low frequency synaptic stimulation (0.1 Hz or 20 Hz/200 ms) evoked NMDAR-EPSCs of small amplitude that showed little memantine block. This is perhaps best explained by the low affinity and relatively rapid kinetics of memantine unblock (Johnson and Kotermanski, 2006). For example, memantine caused significantly less block of NMDA-EPSCs in response to 0.1 Hz than MK-801, most likely due to the markedly different unblocking rates (MacDonald et al., 1991) that allow memantine to rapidly leave the channel during brief synaptic activation, while MK-801 is essentially trapped (Blanpied et al., 1997). The low level block of low-frequency-activated synaptic NMDARs compared with whole-cell NMDARs is unlikely to be due to differences in subunit composition as memantine shows little subunit selectivity in low extracellular Mg2+ (Kotermanski and Johnson, 2009; Otton et al., 2011).

Previous estimates of the block of low frequency-evoked synaptic NMDARs by clinically relevant concentrations of memantine ranged from ~30% (1 mM memantine; Xia et al., 2010) to ~80% (10 μM memantine; Wroge et al., 2012). In SNc dopamine neurones, evoked NMDAR-EPSCs were much smaller in amplitude than in the aforementioned studies, which could explain the much smaller memantine block.

There was a significant positive correlation between memantine block and either amplitude or total charge transfer, consistent with the dynamics of receptor activation being an important factor in determining memantine block; longer duration and high intensity receptor activations (giving a greater charge transfer) are particularly prone to use-dependent block. These findings are consistent with the findings of Wroge et al. (2012), who demonstrated that synaptic NMDARs can in fact be blocked substantially by memantine if the intensity of receptor activity is sufficiently high (Wroge et al., 2012).

4.3. Which patterns of NMDAR activity are likely to occur in PD?

The intensity of NMDAR activation is likely to differ under physiological and pathological conditions. If the extent of memantine block of different receptor populations is determined in large part by the patterns of NMDAR activity, then in order to understand the clinical benefit of memantine it is important to understand which patterns of activity predominate under pathological conditions. In PD, excitatory drive from the subthalamic nucleus to SNc dopamine neurones is increased (Hutchison et al., 1998; Magariños-Ascone et al., 2000; Magnin et al., 2000; Steigerwald et al., 2008; Piallat et al., 2011). In PD patients the proportion of subthalamic nucleus neurones firing in high frequency bursts (>100 Hz) is reportedly increased compared with control subjects (Steigerwald et al., 2008). As memantine robustly blocks NMDAR activity in response to stimulation at 80 Hz it may tend to selectively inhibit pathological glutamatergic signalling and this may contribute to the therapeutic efficacy of memantine in some PD patients.

In PD, a combination of increased glutamatergic drive and membrane depolarisation (due to mitochondrial dysfunction) may converge to compromise voltage-dependent Mg2+ block of both synaptic and extrasynaptic NMDARs. Memantine, carrying a lesser charge (+1), is able to block NMDARs at more depolarised membrane potentials and therefore can potentially restore functional voltage-dependence in an overactive glutamatergic system in which Mg2+ block is compromised (Johnson and Kotermanski, 2006; Lipton, 2006; Parsons et al., 2007; Kotermanski and Johnson, 2009). The experiments presented here show substantial memantine block of whole-cell NMDAR responses during prolonged application of a low concentration of agonist, indicating that another potential therapeutic benefit of memantine may be to compensate for a loss of voltage-dependent Mg2+ block of extrasynaptic NMDARs at depolarised membrane potentials.

Therapeutic drugs should ideally leave physiological function intact. Memantine (10 μM) caused 12–15% block of low frequency-evoked NMDAR-EPSCs, suggesting that more than 80% of low frequency physiological synaptic activity would be preserved. Normal synaptic activity will be accompanied by postsynaptic depolarisation, and the voltage-dependent increase in off-rate will contribute to memantine unblock (Bresink et al., 1996; Frankiewicz et al., 1996; Parsons et al., 2008; Kotermanski and Johnson, 2009); therefore, under physiological conditions NMDAR block may be even less than that observed in recordings at −50 mV.

4.4. Memantine prevents a decrease in the density of TH+ neurones

The density of SNc neurones expressing TH (presumed dopaminergic) was significantly reduced by prolonged treatment of the slice with NMDA, consistent with the idea that NMDA is excitotoxic to dopamine neurones, and in agreement with other studies that have reported this (for example, Johnson and Bywood, 1998; Bywood and Johnson, 2000; Munhall et al., 2012). Memantine was able to prevent this effect of NMDA, whilst having no effect alone. The simplest explanation for these results is that incubation with NMDA caused sufficient Ca2+ influx to induce excitotoxic neuronal death (Hartley et al., 1993). Bath application of NMDA will activate synaptic and extrasynaptic NMDARs, both of which can signal to either necrotic or apoptotic neuronal death pathways if the stimulus is sufficiently strong (Hardingham et al., 2002; Wroge et al., 2012). Apoptotic neuronal death is thought to occur as a result of milder and prolonged activation of NMDARs (Ankarcrona et al., 1995), while necrotic cell death is generally a response to acute and severe glutamatergic insult (Gwag et al., 1997; Sohn et al., 1998). Early stages of necrosis have been observed in cultured cortical neurones after relatively short (2 h) incubations in low concentrations (10–15 μM) of NMDA (Gwag et al., 1997).

It is possible that incubation with 1 mM NMDA for 1h was sufficient to induce necrotic cell death in SNc dopamine neurones, resulting in the observed decrease in the density of TH expressing neurones. Alternatively, it is possible that TH+ neurones are still intact but that expression of TH+ decreases as a result of NMDAR activity; such an effect would impair the ability of dopamine neurones to produce dopamine and if such an effect occurs in PD it could also contribute to the detrimental effects on the nigrostriatal circuitry resulting from the loss of dopamine. NMDAR activity leads to down-regulation of TH activity in rat striatal synaptosomes (Chowdhury and Fillenz, 1991; Desce et al., 1994) and in rat hypothalamic neurones (Bobrovskaya et al., 2004), although block of NMDAR activity reduces TH immunoreactivity in the prefrontal cortex (Wedzony et al., 2005) and NMDAR activity stimulates TH synthesis in rat striatal slices (Arias-Montaño et al., 1992). The excessive NMDAR activity modelled here might have caused down-regulation or complete loss of TH function or expression; further work would be needed to address this.

Memantine incubation alone had no effect on the density of TH expressing neurones, and the density of TH+ neurones did not decrease in the presence of both memantine and NMDA, suggesting that, like MK-801 (for example, Johnson and Bywood, 1998), memantine may be able to reduce excitotoxicity in SNc dopamine neurones. This is in agreement with studies in cortical cultures (Papadia et al., 2008) and in vivo (Chen et al., 1998; Volbracht et al., 2006).

In conclusion, memantine inhibited both synaptic and whole-cell (synaptic and extrasynaptic) NMDAR responses in SNc dopaminergic neurones. The extent of block was dependent on the pattern of NMDAR activation. The substantial block of synaptic NMDARs during high-frequency activation and of small amplitude, long duration whole-cell NMDAR responses suggest that memantine could preferentially inhibit over-active glutamatergic NMDAR signalling, but have negligible effects on low frequency synaptic signalling. These effects may account for some of the therapeutic benefits of memantine. Together, these findings shed light on the factors contributing to the potency of memantine at NMDARs in SNc dopamine neurones and support the idea that memantine has neuroprotective potential in conditions where there is enhanced NMDAR activation.

Acknowledgements

Supported by a PhD Studentship (H-0902) to ARW from Parkinson’s UK and by The Isaac Newton Trust, Trinity College Cambridge.

References

- Ankarcrona M, Dypbukt JM, Bonfoco E, Zhivotovsky B, Orrenius S, Lipton SA, Nicotera P. Glutamate-induced neuronal death: a succession of necrosis or apoptosis depending on mitochondrial function. Neuron. 1995;15(4):961–973. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90186-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias-Montaño JA, Martínez-Fong D, Aceves J. Glutamate stimulation of tyrosine hydroxylase is mediated by NMDA receptors in the rat striatum. Brain Res. 1992;569:317–322. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90645-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blandini F, Nappi G, Tassorelli C, Martignoni E. Functional changes of the basal ganglia circuitry in Parkinson’s disease. Prog. Neurobiol. 2000;62(1):63–88. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(99)00067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanpied TA, Boeckman FA, Aizenman E, Johnson JW. Trapping channel block of NMDA-activated responses by amantadine and memantine. J. Neurophysiol. 1997;77:309–323. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.1.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobrovskaya L, Dunkley PR, Dickson PW. Phosphorylation of Ser19 increases both Ser40 phosphorylation and enzyme activity of tyrosine hydroxylase in intact cells. J. Neurochem. 2004;90:857–864. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bresink I, Benke TA, Collett VJ, Seal AJ, Parsons CG, Henley JM, Collingridge GL. Effects of memantine on recombinant rat NMDA receptors expressed in HEK 293 cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;119:195–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15971.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brothwell SLC, Barber JL, Monaghan DT, Jane DE, Gibb AJ, Jones S. NR2B- and NR2D-containing synaptic NMDA receptors in developing rat substantia nigra pars compacta dopaminergic neurones. J. Physiol. 2008;586:739–750. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.144618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bywood PT, Johnson SM. Differential vulnerabilities of substantia nigra catecholamine neurons to excitatory amino acid-induced degeneration in rat midbrain slices. Exp. Neurol. 2000;162:180–188. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2000.7310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HS, Lipton SA. The chemical biology of clinically tolerated NMDA receptor antagonists. J. Neurochem. 2006;97:1611–1626. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HS, Lipton SA. Mechanism of memantine block of NMDA-activated channels in rat retinal ganglion cells: uncompetitive antagonism. J. Physiol. 1997;499(Pt 1):27–46. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1997.sp021909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HS, Wang YF, Rayudu PV, Edgecomb P, Neill JC, Segal MM, Lipton SA, Jensen FE. Neuroprotective concentrations of the N-methyl-D-aspartate open-channel blocker memantine are effective without cytoplasmic vacuolation following post-ischemic administration and do not block maze learning or long-term potentiation. Neuroscience. 1998;86:1121–1132. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00163-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury M, Fillenz M. Presynaptic adenosine A2 and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors regulate dopamine synthesis in rat striatal synaptosomes. J. Neurochem. 1991;56:1783–1788. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb02081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cull-Candy SG, Leszkiewicz DN. Role of distinct NMDA receptor subtypes at central synapses. Sci. STKE. 2004;255:re16. doi: 10.1126/stke.2552004re16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danysz W, Parsons CG, Kornhuber J, Schmidt WJ, Quack G. Amino-adamantanes as NMDA receptor antagonists and antiparkinsonian agents – preclinical studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 1997;21:455–468. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(96)00037-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danysz W, Parsons CG, Quack G. NMDA channel blockers: memantine and amino-aklylcyclohexanes – in vivo characterization. Amino Acids. 2000;19:167–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desce JM, Godeheu G, Galli T, Glowinski J, Cheramy A. Opposite pre-synaptic regulations by glutamate through NMDA receptors of dopamine synthesis and release in rat striatal synaptosomes. Brain Res. 1994;640:205–214. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91874-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doble A. The role of excitotoxicity in neurodegenerative disease: implications for therapy. Pharmacol. Ther. 1999;81:163–221. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(98)00042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallon JH, Loughlin SE. Substantia nigra. In: Paxinos G, editor. The Rat Nervous System. second ed. Academic Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Frankiewicz T, Potier B, Bashir ZI, Collingridge GL, Parsons CG. Effects of memantine and MK-801 on NMDA-induced currents in cultured neurones and on synaptic transmission and LTP in area CA1 of rat hippocampal slices. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;117:689–697. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15245.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilling KE, Jatzke C, Parsons CG. Agonist concentration dependency of blocking kinetics but not equilibrium block of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors by memantine. Neuropharmacology. 2007;53:415–420. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwag BJ, Koh JY, DeMaro JA, Ying HS, Jacquin M, Choi DW. Slowly triggered excitotoxicity occurs by necrosis in cortical cultures. Neuroscience. 1997;77:393–401. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00473-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallett PJ, Standaert DG. Rationale for and use of NMDA receptor antagonists in Parkinson’s disease. Pharmacol. Ther. 2004;102:155–174. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardingham GE, Bading H. Synaptic versus extrasynaptic NMDA receptor signalling: implications for neurodegenerative disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2010;11:682–696. doi: 10.1038/nrn2911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardingham GE, Fukunaga Y, Bading H. Extrasynaptic NMDARs oppose synaptic NMDARs by triggering CREB shut-off and cell death pathways. Nat. Neurosci. 2002;5:405–414. doi: 10.1038/nn835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley DM, Kurth MC, Bjerkness L, Weiss JH, Choi DW. Glutamate receptor-induced 45Ca2+ accumulation in cortical cell culture correlates with subsequent neuronal degeneration. J. Neurosci. 1993;13:1993–2000. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-05-01993.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesselink MB, De Boer BG, Breimer DD, Danysz W. Brain penetration and in vivo recovery of NMDA receptor antagonists amantadine and memantine: a quantitative microdialysis study. Pharm. Res. 1999;16:637–642. doi: 10.1023/a:1018856020583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higley MJ, Soler-Llavina GJ, Sabatini BL. Cholinergic modulation of multivesicular release regulates striatal synaptic potency and integration. Nat. Neurosci. 2009;12:1121–1128. doi: 10.1038/nn.2368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison WD, Allan RJ, Opitz H, Levy R, Dostrovsky JO, Lang AE, Lozano AM. Neurophysiological identification of the subthalamic nucleus in surgery for Parkinson’s disease. Ann. Neurol. 1998;44:622–628. doi: 10.1002/ana.410440407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SM, Bywood PT. Excitatory amino acid-induced degeneration of dendrites of catecholamine neurons in rat substantia nigra. Exp. Neurol. 1998;151:229–236. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1998.6783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JW, Kotermanski SE. Mechanism of action of memantine. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2006;6:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones S, Gibb AJ. Functional NR2B- and NR2D-containing NMDA receptor channels in rat substantia nigra dopaminergic neurones. J. Physiol. 2005;569:209–221. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.095554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashiwagi K, Masuko T, Nguyen CD, Kuno T, Tanaka I, Igarashi K, Williams K. Channel blockers acting at N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors: differential effects of mutations in the vestibule and ion channel pore. Mol. Pharmacol. 2002;61(3):533–545. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.3.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp JA, McKernan RM. NMDA receptor pathways as drug targets. Nat. Neurosci. 2002;5:1039–1042. doi: 10.1038/nn936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotermanski SE, Johnson JW. Mg2+ imparts NMDA receptor subtype selectivity to the Alzheimer’s drug memantine. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:2774–2779. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3703-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krystal JH, Karper LP, Seibyl JP, Freeman GK, Delaney R, Bremner JD, Heninger GR, Bowers MB, Charney DS. Subanesthetic effects of the noncompetitive NMDA antagonist, ketamine, in humans. Psychotomimetic, perceptual, cognitive, and neuroendocrine responses. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1994;51:199–214. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950030035004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau CG, Zukin RS. NMDA receptor trafficking in synaptic plasticity and neuropsychiatric disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007;8:413–426. doi: 10.1038/nrn2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipton SA. Failures and successes of NMDA receptor antagonists: molecular basis for the use of open-channel blockers like memantine in the treatment of acute and chronic neurologic insults. NeuroRx. 2004;1:101–110. doi: 10.1602/neurorx.1.1.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipton SA. Paradigm shift in neuroprotection by NMDA receptor blockade: memantine and beyond. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2006;5:160–170. doi: 10.1038/nrd1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipton SA. Pathologically activated therapeutics for neuroprotection. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007;8:803–808. doi: 10.1038/nrn2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisman JE, Raghavachari S, Tsien RW. The sequence of events that underlie quantal transmission at central glutamatergic synapses. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007;8:597–609. doi: 10.1038/nrn2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litvinenko IV, Odinak MM, Mogil’naya VI, Perstnev SV. Use of memantine (akatinol) for the correction of cognitive impairments in Parkinson’s disease complicated by dementia. Neurosci. Behav. Physiol. 2010;40:149–155. doi: 10.1007/s11055-009-9244-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low SJ, Roland CL. Review of NMDA antagonist-induced neurotoxicity and implications for clinical development. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2004;42:1–14. doi: 10.5414/cpp42001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald JF, Bartlett MC, Mody I, Pahapill P, Reynolds JN, Salter MW, Schneiderman JH, Pennefather PS. Actions of ketamine, phencyclidine and MK-801 on NMDA receptor currents in cultured mouse hippocampal neurones. J. Physiol. 1991;432:483–508. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magariños-Ascone CM, Figueiras-Mendez R, Riva-Meana C, Córdoba-Fernández A. Subthalamic neuron activity related to tremor and movement in Parkinson’s disease. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2000;12:2597–2607. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnin M, Morel A, Jeanmonod D. Single-unit analysis of the pallidum, thalamus and subthalamic nucleus in parkinsonian patients. Neuroscience. 2000;96:549–564. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00583-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis EB, Lock H, Hjelmstad GO, Fields HL. The ventral tegmental area revisited: is there an electrophysiological marker for dopaminergic neurons? J. Physiol. 2006;577:907–924. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.117069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munhall AC, Wu YN, Belknap JK, Meshul CK, Johnson SW. NMDA alters rotenone toxicity in rat substantia nigra zona compacta and ventral tegmental area dopamine neurons. Neurotoxicology. 2012;33:429–435. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuhoff H, Neu A, Liss B, Roeper J. I(h) channels contribute to the different functional properties of identified dopaminergic subpopulations in the midbrain. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:1290–1302. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-04-01290.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otton HJ, Lawson-McLean A, Pannozzo MA, Davies CH, Wyllie DJ. Quantification of the Mg2+-induced potency shift of amantadine and memantine voltage-dependent block in human recombinant GluN1/GluN2A NMDARs. Neuropharmacology. 2011;60:388–396. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadia S, Soriano FX, Léveillé F, Martel MA, Dakin KA, Hansen HH, Kaindl A, Sifringer M, Fowler J, Stefovska V, McKenzie G, Craigon M, Corriveau R, Ghazal P, Horsburgh K, Yankner BA, Wyllie DJ, Ikonomidou C, Hardingham GE. Synaptic NMDA receptor activity boosts intrinsic antioxidant defenses. Nat. Neurosci. 2008;11:476–487. doi: 10.1038/nn2071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons CG, Gilling KE, Jatzke C. Blocking kinetics of memantine on NR1a/2A receptors recorded in inside-out and outside-out patches from Xenopus oocytes. J. Neural Transm. 2008;115:1367–1373. doi: 10.1007/s00702-008-0087-7. 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons CG, Stöffler A, Danysz W. Memantine: a NMDA receptor antagonist that improves memory by restoration of homeostasis in the glutamatergic system – too little activation is bad, too much is even worse. Neuropharmacology. 2007;53:699–723. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piallat B, Polosan M, Fraix V, Goetz L, David O, Fenoy A, Torres N, Quesada JL, Seigneuret E, Pollak P, Krack P, Bougerol T, Benabid AL, Chabardès S. Subthalamic neuronal firing in obsessive–compulsive disorder and Parkinson disease. Ann. Neurol. 2011;69:793–802. doi: 10.1002/ana.22222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomarol-Clotet E, Honey GD, Murray GK, Corlett PR, Absalom AR, Lee M, McKenna PJ, Bullmore ET, Fletcher PC. Psychological effects of ketamine in healthy volunteers. Phenomenological study. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2006;189:173–179. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.015263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puzin MN, Krivonos OV, Kozhevnikova ZV. Akatinol memantine in the therapy of cognitive disorders in Parkinson’s disease. Zh. Nevrol. Psikhiatr. Im. S. S. Korsakova. 2007;95:93–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabey JM, Nissipeanu P, Korczyn AD. Efficacy of memantine, an NMDA receptor antagonist, in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. J. Neural Transm. Park. Dis. Dement. Sect. 1992;4:277–282. doi: 10.1007/BF02260076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohn S, Kim EY, Gwag BJ. Glutamate neurotoxicity in mouse cortical neurons: atypical necrosis with DNA ladders and chromatin condensation. Neurosci. Lett. 1998;240:147–150. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00936-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steigerwald F, Pötter M, Herzog J, Pinsker M, Kopper F, Mehdorn H, Deuschl G, Volkmann J. Neuronal activity of the human subthalamic nucleus in the parkinsonian and nonparkinsonian state. J. Neurophysiol. 2008;100:2515–2524. doi: 10.1152/jn.90574.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suárez F, Zhao Q, Monaghan DT, Jane DE, Jones S, Gibb AJ. Functional heterogeneity of NMDA receptors in rat substantia nigra pars compacta and reticulata neurones. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2010;32:359–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07298.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volbracht C, Van Beek J, Zhu C, Blomgren K, Leist M. Neuroprotective properties of memantine in different in vitro and in vivo models of excitotoxicity. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2006;23:2611–2622. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vry J, Jentzsch KR. Role of the NMDA receptor NR2B subunit in the discriminative stimulus effects of ketamine. Behav. Pharmacol. 2003;14:229–235. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200305000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washio H, Takigachi-Hayashi K, Konishi S. Early postnatal development of substantia nigra neurons in rat midbrain slices: hyperpolarization-activated inward current and dopamine-activated current. Neurosci. Res. 1999;34:91–101. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(99)00039-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wedzony K, Fijał K, Chocyk A. Blockade of NMDA receptors in postnatal period decreased density of tyrosine hydroxylase immunoreactive axonal arbors in the medial prefrontal cortex of adult rats. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2005;56:205–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wroge CM, Hogins J, Eisenman L, Mennerick S. Synaptic NMDA receptors mediate hypoxic excitotoxic death. J. Neurosci. 2012;32:6732–6742. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6371-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia P, Chen H-SV, Zhang D, Lipton SA. Memantine preferentially blocks extrasynaptic over synaptic NMDA receptor currents in hippocampal autapses. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:11246–11250. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2488-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]