Abstract

Lesions that remove neurons expressing neurokinin-1 (NK1) receptors from the nucleus tractus solitarii (NTS) without removing catecholaminergic neurons lead to loss of baroreflexes, labile arterial pressure, myocardial lesions, and sudden death. Because destruction of NTS catecholaminergic neurons expressing tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) may also cause lability of arterial pressure and loss of baroreflexes, we sought to test the hypothesis that cardiac lesions associated with lability are not dependent on damage to neurons with NK1 receptors but would also occur when TH neurons in NTS are targeted. To rid the NTS of TH neurons we microinjected anti-dopamine β-hydroxylase conjugated to saporin (anti-DBH-SAP, 42 ng/200 nl) into the NTS. After injection of the toxin unilaterally, immunofluorescent staining confirmed that anti-DBH-SAP decreased the number of neurons and fibers that contain TH and DBH in the injected side of the NTS while sparing neuronal elements expressing NK1 receptors. Bilateral injections in eight rats led to significant lability of arterial pressure. For example, on day 8 standard deviation of mean arterial pressure was 16.8 ± 2.5 mmHg when compared with a standard deviation of 7.83 ± 0.33 mmHg in six rats in which phosphate buffered saline (PBS) had been injected bilaterally. Two rats died suddenly at 5 and 8 days after anti-DBH-SAP injection. Seven-treated animals demonstrated microscopic myocardial necrosis as reported in animals with lesions of NTS neurons expressing NK1 receptors. Thus, cardiac and cardiovascular effects of lesions directed toward catecholamine neurons of the NTS are similar to those following damage directed toward NK1 receptor-containing neurons.

Keywords: Arrhythmia, Baroreflex, Catecholamine, Lability, Rat, Saporin

Introduction

In previous studies (Riley et al. 2002; Nayate et al. 2008) we made selective lesions of neurons that express the NK1 receptor in the nucleus tractus solitarii (NTS) and found that rats with those lesions were prone to sudden death and myocardial lesions as may be seen in humans after central lesions (Talman and Kelkar 1993). In addition, treated animals manifested lability of arterial blood pressure (Nayate et al. 2008), a cardinal sign in animals with central (Snyder et al. 1978; Talman et al. 1980) or peripheral (Cowley et al. 1973; Junqueira and Krieger 1976) interruption of baroreceptor reflex pathways. Indeed, treated animals demonstrated attenuation of baroreflex influences on cardiac rate in response to increases or decreases of arterial blood pressure (Riley et al. 2002). We found that central lesions that had been made by injection of stabilized substance P conjugated to the toxic lectin saporin (SSP-SAP), caused loss of neurons with the NK1 receptor (Nayate et al. 2008), but neurons with tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) were not lost (unpublished observation). Some studies have shown that lesions of TH-containing neurons in NTS led to attenuation of the baroreflex as well as chronic lability of arterial blood pressure (Snyder et al. 1978; Talman et al. 1980) while other studies have questioned that finding (Itoh et al. 1992). We conjectured that pathological influences on the myocardium and on cardiac rhythm when NTS lesions had been produced by SSP-SAP related to disturbed baroreflex function and to lability of arterial pressure but not to a specific transmitter in the baroreflex arc. Therefore, we hypothesized that lesions concentrated in catecholamine neurons of the NTS would also lead to sudden death and to myocardial lesions if the catecholamine neuronal lesions caused lability of arterial pressure. To produce lesions of NTS catecholamine neurons we injected an antibody to dopamine β-hydroxylase conjugated to saporin (anti-DBH-SAP) as has been used in other studies to locally and selectively kill catecholamine neurons (Madden et al. 1999).

Methods

All procedures were reviewed and approved by the University of Iowa Animal Care and Use Committee and complied with standards stated in the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, 3rd edition (1996) (National Research Council 1996). All efforts were made to minimize the number of animals used and to avoid their experiencing pain or distress.

General Instrumentation

We studied adult (250–300 g) male Sprague–Dawley rats that were instrumented as previously described (Nayate et al. 2008) with Data Sciences International (DSI) radiotelemetry transducers (St. Paul, MN). The transducers were placed in the abdominal cavity through a midline abdominal incision made while the animal was under general anesthesia with isoflurane (2 %), and the cannula from the transducer was inserted into a femoral artery. The DSI transducer is capable of chronic recording of arterial pressure (AP), mean AP (MAP), heart rate (HR), electrocardiographic activity (ECG), and body temperature. While still deeply anesthetized, animals were placed in a stereotaxic frame in preparation for microinjections into the brain. As previously described (Riley et al. 2002), the brain stem was exposed through a dorsal midline incision in the neck to the base of the skull and, the dorsal surface of the brain stem was exposed for full visualization of the surface of the dorsal vagal complex. Glass micropipettes (diameter of 20–30 μm) filled with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; N = 6) or anti-DBH-SAP (42 ng in 200 nl; N = 8) in PBS were placed under stereotaxic control in the NTS (0.4 mm rostral to the calamus scriptorius, 0.5 mm lateral to the midline, and 0.5 mm below the dorsal surface of the brain stem at that site). Microinjections were made bilaterally in small (25–50 nl) increments. A total volume (200 nl) of injection was made within 15 min after which the pipette was left in the brain stem for an additional 15 min to reduce efflux of fluid from the pipette track. Hemostasis, wound closure, and analgesia with buprenorphine (0.01 mg/kg) were achieved; and, after termination of general anesthesia, animals were returned to their home cage. The cage was placed on a DSI receiver plate that monitored physiological variables and sent those data to a storage computer for later access. Data were collected at 500 Hz for 8 days. On the 8th day animals were euthanized with an overdose (150 mg/kg) of pentobarbital and the hearts were removed for pathological examination. To examine pathological changes in the heart, we fixed and stored the heart in 4 % paraformaldehyde in PBS (pH 7.4) until it was embedded in paraffin. Transverse sections were then cut and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained slides prepared at 2 mm intervals throughout the entire heart.

Immunofluorescent Staining and Confocal Microscopy

To assess efficacy of anti-DBH-SAP in ridding the NTS of catecholamine neurons, we utilized antibodies to TH, DBH, and the NK1 receptor to determine effects on those proteins. In studies of the anatomical effect of anti-DBH-SAP we injected the toxic conjugate unilaterally into the NTS of (N = 6) animals that were not instrumented for recording physiological variables. Seven days after injections animals were anesthetized with pentobarbital (50 mg/kg) and perfused with 4 % paraformaldehyde through the heart. The brain was removed, postfixed for 2 h in 4 % paraformaldehyde, and then cryoprotected for 2 days in 30 % sucrose in PBS at 4 °C. Frozen 20 μm coronal sections of the brain stem were cut with a cryostat and processed for immunofluorescent staining. Procedures similar to those described in our previous publications (Lin et al. 2007, 2008) were used for immunofluorescent staining of brain stem sections. In brief, brain stem sections were incubated in mouse anti-DBH (1:500, Chemicon, USA) or rabbit anti-TH (1:100, Chemicon, USA) or rabbit anti-NK1 receptor (1:10, Novus, USA) in 10 % donkey normal serum for 24 h in a humid chamber at 25 °C. We then washed the sections with PBS and incubated them for 20–24 h at 4 °C in PBS that contained rhodamine X (RRX) or fluorescein (FITC)-conjugated secondary antibody made in donkey (1:200, Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs, USA). Stained sections were washed and mounted with Prolong Gold Antifade Reagents (Invitrogen-Molecular Probes, USA). We analyzed labeled sections with a Zeiss LSM 510 or Zeiss LSM 710 confocal laser scanning microscope as described previously (Lin and Talman 2006; Lin et al. 2007). Confocal images were obtained and processed with software provided with the Zeiss LSM 510 or Zeiss LSM 710.

Sequence Analysis of the Baroreflex

Baroreflex activity was assessed by the sequence technique as first described by Bertinieri et al. (1985) and modified by Stauss et al. (2006). In summary, AP was assessed telemetrically at a rate of 500 Hz for 10 s periods per minute for all days postoperatively. Sequence analysis was applied to the recordings obtained during the night time (6:00 PM to 6:00 AM) of the last 24 h of the experimental protocol. For each continuous 10 s sampling interval, sequences of three or more sequential increases or decreases in systolic pressure with corresponding increases or decreases in interbeat interval, i.e., baroreflex sequences were detected. For each sequence the slope of the linear regression line was determined and the slopes of all sequences averaged into a single baroreflex sensitivity value for each animal. Baroreflex effectiveness index was determined as the ratio of baroreflex sequences to blood pressure ramps (continuous increases or decreases in systolic pressure) as described by di Rienzo et al. (2001).

Statistical Analysis

Lability was quantified as the standard deviation (SD) of MAP. All data were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SE), and the control and experimental group results were subjected to independent Student’s t test with significance accepted at a p value ≤0.05.

Results

Immunofluorescent Confocal Analysis of Effects of anti-DBH-SAP in NTS

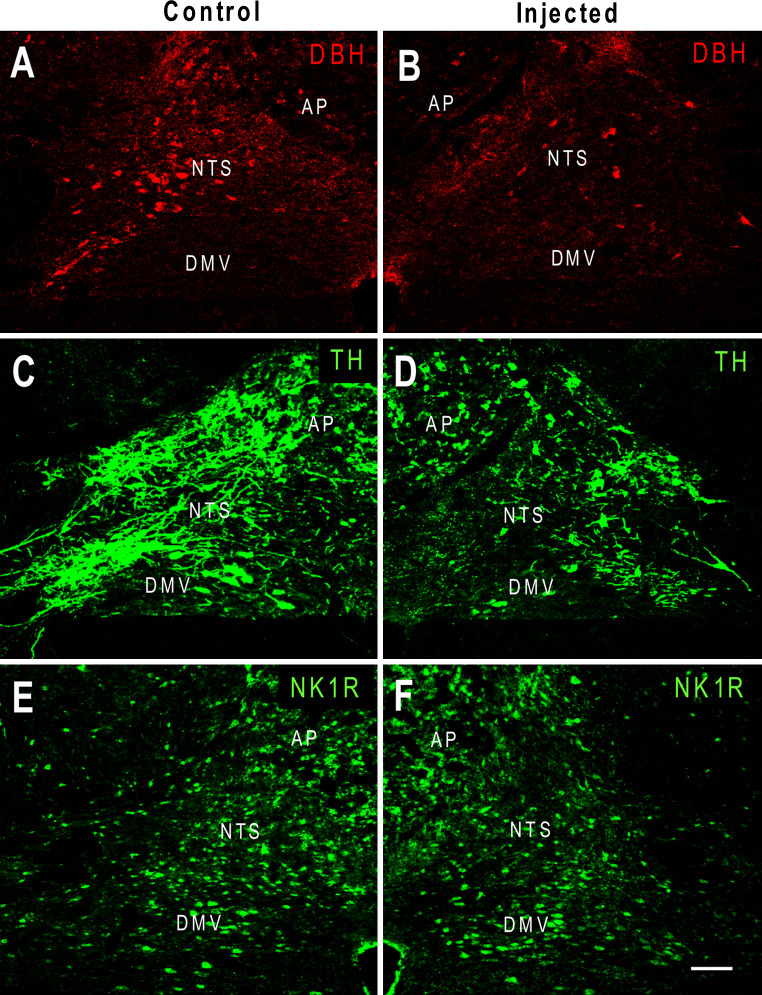

Unilateral microinjection of anti-DBH-SAP produced noticeable reductions in TH-IR and DBH-IR but not NK1 receptor-IR when compared with the contralateral, control side of the NTS (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Pseudo-colored confocal images showing fluorescent immunostaining of DBH (a, b), TH (c, d), and NK1 receptors (e, f) in the rat NTS after anti-DBH-SAP was injected unilaterally into the NTS. The un-injected side served as an intra-animal intra-section control. Compared to the un-injected side (a, c), the injected NTS (b, d) shows a decrease in DBH-immunoreactivity (IR) and TH-IR. No obvious change in NK1 receptor-IR was seen in the injected side (f) when compared to that of the control side (e). AP area postrema and DMV dorsal motor nucleus of vagus, scale bar 100 μm

Effect on AP, HR, and ECG

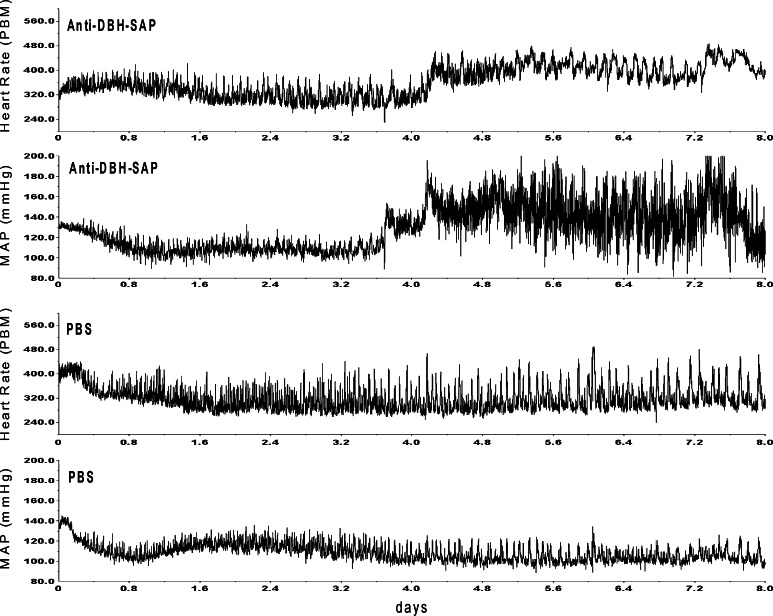

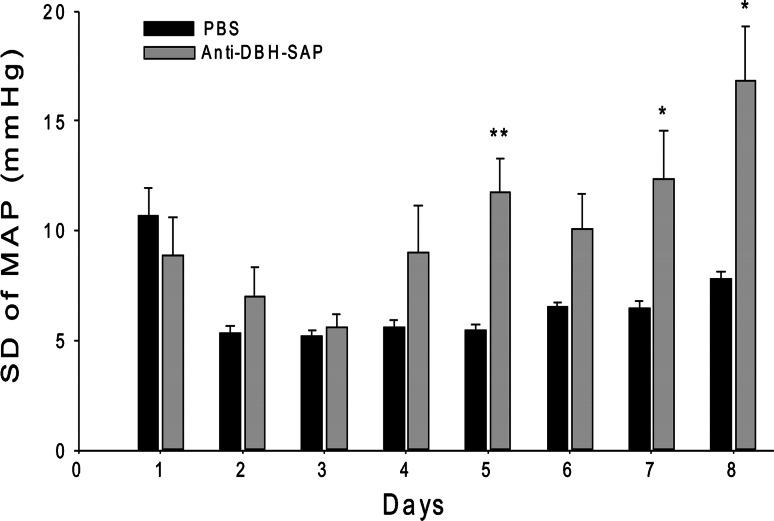

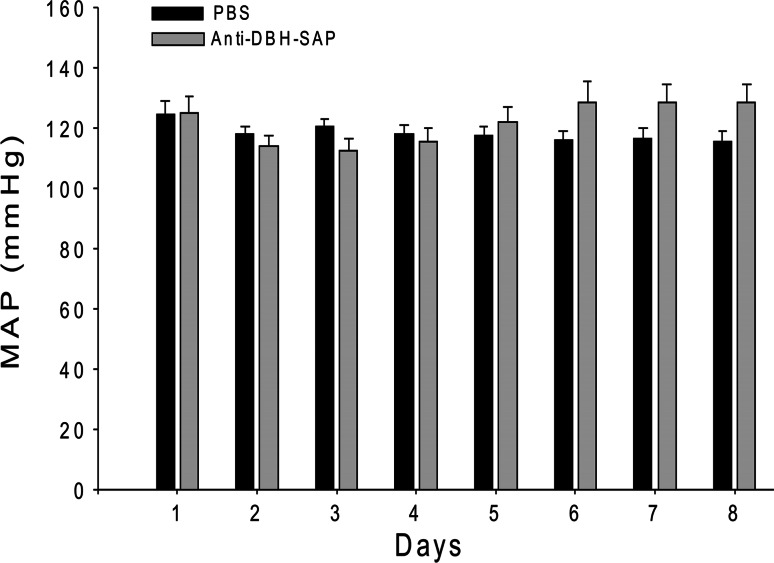

After bilateral injection of anti-DBH-SAP into the NTS of eight rats, mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) became labile over the week after surgery (Fig. 2) and reached maximal levels of lability (SD of 16.8 ± 2.5 mmHg) that was significantly (p = 0.013) greater than maximal lability (SD of 7.83 ± 0.33 mmHg) seen at any time after injection of PBS into NTS of six control rats (Fig. 3). Mean levels of AP fell slightly during the first postoperative week both in treated and in sham operated control animals but then gradually increased (Figs. 2, 4). However, at the same postoperative time when SD had reached its maximum for each animal, there was no significant difference in MAP between the group treated with anti-DBH-SAP (128.6 ± 6.0 mmHg) and the group treated with PBS (115.6 ± 3.7 mmHg).

Fig. 2.

Bilateral microinjection of anti-DBH-SAP into the NTS led to increased lability and levels of arterial pressure in this representative animal (top tracings) between 4 and 5 days after surgery (Day 0) when compared with the same variables in a representative control (PBS) animal (bottom tracings). In other animals, as here, we saw a decrease in heart rate and MAP prior to an increase in both variables. As a group the treated animals did not become significantly hypertensive (see Fig. 4)

Fig. 3.

In animals in which anti-DBH-SAP had been injected bilaterally into the NTS there was a transient decline in lability (SD of MAP) from the 1st until the 4th day after surgery when SD began to rise, reaching significantly (**p = 0.004) increased levels on day 5 when compared with those of control rats. Comparison of the SD at individual days revealed significant differences between treated and control animals also on day 7 (*p = 0.034) and day 8 (*p = 0.013). The SD of MAP for day 1 is shown but was not included in analysis because it was artificially elevated as a result of data collection as the animals were recovering from anesthesia

Fig. 4.

In eight animals in which anti-DBH-SAP had been injected bilaterally into the NTS there was a transient decline in MAP from the 1st to 4th day after surgery. After the 4th day pressure began to rise and reached a maximum (128.9 ± 6.8 mmHg) at day 6 when AP was not significantly different from that on day 1 and did not change significantly at days 7 and 8

Effect on the Baroreflex

Sequence analysis for baroreflex function revealed significantly (p = 0.04) blunted baroreflex responses in animals treated with anti-DBH-SAP when compared with those treated with PBS. In the former group the average slope of baroreflex sequences (i.e., baroreflex sensitivity) was 1.49 ± 0.24 ms/mmHg while in the latter control group the slope was 2.23 ± 0.15 ms/mmHg. Furthermore, baroreflex effectiveness index was 4.66 ± 0.67 % in the control group but only 2.51 ± 1.04 % in the treated group.

Sudden Death and Cardiac Changes

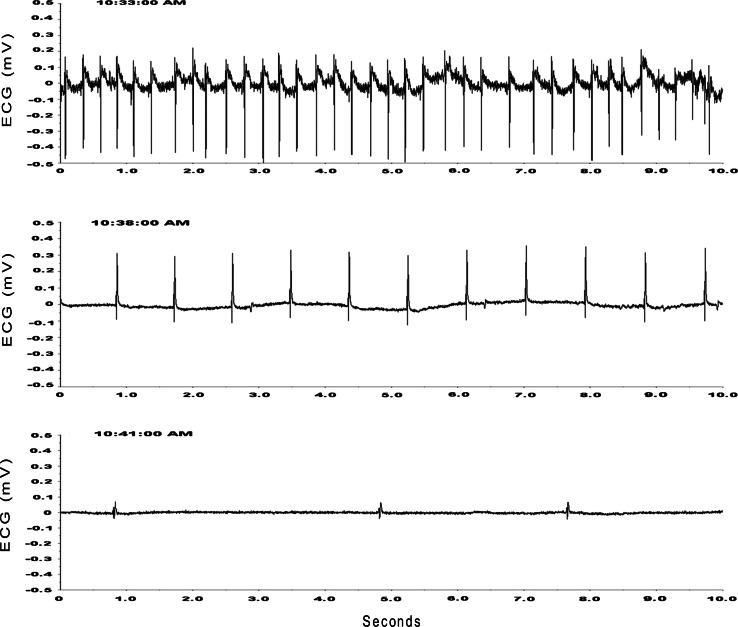

Two-treated animals died suddenly on the fifth and 8th day postoperatively, respectively (Figs. 5, 6). Neither animal showed signs of impending fatality until the final day when the ECG (Fig. 6) began to show a change in contour of the QRS complex, slowing of cardiac rate and ultimately asystole (Fig. 6). The ECG then evolved from a sinus rhythm to a junctional rhythm prior to asystole and death, all within 8–10 min.

Fig. 5.

This representative animal received bilateral injections of anti-DBH-SAP into NTS and within 4 days had begun to express increased lability of AP. Though the animal had recovered from surgery (eating, grooming, drinking, and moving about the cage) it suddenly died during the 8th day after surgery (see Fig. 6 for electrocardiographic-ECG-recording)

Fig. 6.

ECG recording in the same animal whose arterial pressure is depicted in Fig. 5. The ECG evolves from a sinus rhythm with clear p waves (top trace) to a junctional rhythm (center trace) followed by a ventricular rhythm, asystole, and death (bottom trace) within 8 min

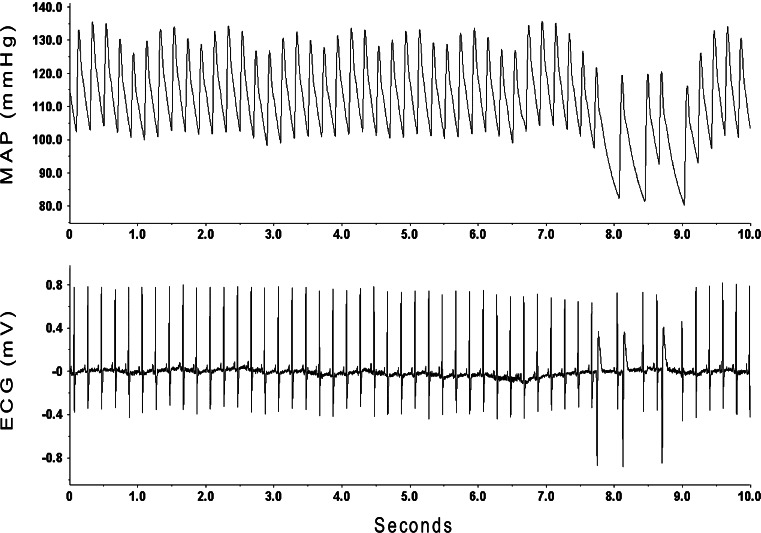

Although sudden death that occurred in the two animals came as a result of asystole, we found that animals treated with anti-DBH-SAP manifested frequent ventricular ectopic beats (Fig. 7) that were rarely seen in control animals.

Fig. 7.

Animals treated with anti-DBH-SAP manifested frequent ventricular ectopic beats that were rarely seen in control animals. ECG recordings from this representative animal that had been treated with anti-DBH-SAP show runs of premature ventricular beats (lower trace) with accompanying falls in AP (upper trace)

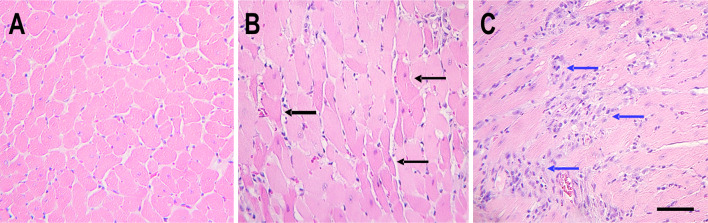

Both the animals that died and all but one of the other treated animals manifested damage to cardiac myocytes. The damage ranged from coagulation necrosis to more extensive subacute changes in the myocardium (Fig. 8). None of these changes, however, corresponded to the territory of coronary arteries but were diffusely distributed in the myocardium. We never found myocardial changes in hearts of control animals.

Fig. 8.

Representative H&E stained sections of hearts of a control animal (a) and animals that had received anti-DBH-SAP bilaterally injected into the NTS (b, c). Some anti-DBH-SAP-treated animals showed diffuse eosinophilic cardiac myocytes consistent with coagulation necrosis (b, black arrows) and others had widely dispersed microscopic areas of basophilic staining (c, blue arrows) consistent with more chronic damage to cardiac myocytes scale bar = 100 μm

Discussion

This study shows that central lesions concentrated in catecholamine neurons of the NTS blunt the baroreflex and lead to arterial blood pressure lability, a hallmark of baroreflex dysfunction (Nathan and Reis 1977; Snyder et al. 1978; Talman et al. 1980; Cowley et al. 1973). The lesions led to cardiac arrhythmias and death in some animals and to diffuse microscopic damage to cardiac myocytes in most animals. In our previous studies (Riley et al. 2002; Nayate et al. 2008) in which we used toxic conjugates of saporin to kill NTS neurons that express NK1 receptors, we found that cardiac damage was correlated with lability of arterial pressure. Our hypothesis had been that interference with baroreflex signaling in the NTS would lead to cardiac damage, but the lesions we had produced were concentrated in neurons that expressed NK1 receptors. Thus, the study raised the possibility that transmission of baroreflex signals through substance P pathways could specifically be involved in creating the cardiac damage associated with the lesion. We suggested that loss of NK1 receptor-containing neurons in NTS could account for the cardiac events because of disordered cardiovascular homeostasis with resulting lability of arterial pressure and that any lesion, which might similarly result in lability of AP, could have the same effect on the heart. We had found that SSP-SAP, while markedly reducing NK1 receptor immunoreactivity in NTS did not reduce TH-immunoreactivity in NTS. In fact, TH-IR was increased in NTS after treatment with SSP-SAP (Lin et al. 2012). This study shows that treating NTS with a toxin that affects TH and DBH-containing neurons while sparing NK1 receptor-immunoreactivity leads to similar changes in AP homeostasis and to cardiac damage and arrhythmias. Thus, this study suggests that those events are not due to interference with one specific and selective transmitter pathway but instead to NTS damage that leads to lability of AP. We acknowledge, however, that lack of change in NK1 receptor immunoreactivity does not mean that lesions produced by anti-DBH-SAP did not affect the function of NK1 (or other) neurons in NTS. Our data, therefore, only show that lesions concentrated in one group of neurons may produce similar results as seen with lesions concentrated in other nearby neurons. Thus, it is possible that the cardiovascular effects of anti-DBH-SAP are the result of effects on NTS neurons other than those with TH/DBH or the result of a combined effect on multiple neuronal types as was seen when NK1R was targeted (Lin et al. 2012). We do not know the precise mechanisms by which NK1 receptors and DBH lesioning in the NTS alter baroreflex function or if effects of anti-DBH-SAP and SSP-SAP share common pathways. Future studies are needed to answer these questions. However, in that anti-DBH-SAP in this study affected TH/DBH neurons the effect on baroreflex function could be due to interference with catecholaminergic transmission in NTS as has been suggested by others (Massari et al. 1996).

For this study we chose to use a toxic conjugate that is reported to be highly selective for central catecholamine neurons (Madden et al. 1999; Madden and Sved 2003; Rinaman 2003) and unlike 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA), which has been used in other studies (Snyder et al. 1978; Itoh et al. 1992), to avoid damage to local neurons that do not contain TH or DBH. Some controversy surrounds previous studies that utilized 6-OHDA to kill NTS catecholamine neurons in that one study showed lability of AP with baroreflex dysfunction (Snyder et al. 1978) while another suggested that the earlier effects had resulted from an excess dose that had caused indiscriminate damage to NTS neurons (Itoh et al. 1992). This study, while not addressing the effects of 6-OHDA, does show that lesions affecting catecholamine neurons, while sparing other local neurons, does lead to lability of arterial pressure. That finding supports a modulatory role for NTS catecholamine neurons in central AP control and suggests that disturbance of that modulation can lead not only to disturbed AP control but also to cardiac damage and arrhythmias independent of a demonstrable effect on central NK1 receptor-containing neurons.

Acknowledgments

The study presented here was supported by National Institutes of Health RO1 HL 088090 (to L. H. Lin and W. T. Talman) and in part by a Department of Veterans Affairs Merit Review (to W. T. Talman). The authors gratefully acknowledge technical support provided by Dr. Wei Zhang in the initial microinjection studies and consultative support from Dr. Harald Stauss in sequence analysis of baroreflex function.

Conflict of interest

None of the authors has a real or perceived conflict of interest that could have, in any way, influenced the results or interpretation of the results of this study.

References

- Bertinieri G, di Rienzo M, Cavallazzi A, Ferrari AU, Pedotti A, Mancia G (1985) A new approach to analysis of the arterial baroreflex. J Hypertens Suppl 3:S79–S81 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowley AW, Liard JF, Guyton AC (1973) Role of the baroreceptor reflex in daily control of arterial blood pressure and other variables in dogs. Circ Res 32:564–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- di Rienzo M, Parati G, Castiglioni P, Tordi R, Mancia G, Pedotti A (2001) Baroreflex effectiveness index: an additional measure of baroreflex control of heart rate in daily life. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 280:R744–R751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh H, Alper RH, Buñag RD (1992) Baroreflex changes produced by serotonergic or catecholaminergic lesions in the rat nucleus tractus solitarius. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 261:225–233 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junqueira LF, Krieger EM (1976) Blood pressure and sleep in the rat in normotension and in neurogenic hypertension. J Physiol (London) 259:725–735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L-H, Talman WT (2006) Vesicular glutamate transporters and neuronal nitric oxide synthase colocalize in aortic depressor afferent neurons. J Chem Neuroanat 32:54–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin LH, Taktakishvili O, Talman WT (2007) Identification and localization of cell types that express endothelial and neuronal nitric oxide synthase in the rat nucleus tractus solitarii. Brain Res 1171:42–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin LH, Taktakishvili OM, Talman WT (2008) Colocalization of neurokinin-1,N-methyl-d-aspartate, and AMPA receptors on neurons of the rat nucleus tractus solitarii. Neuroscience 154:690–700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L-H, Nitschke Dragon D, Talman WT (2012) Collateral damage and compensatory changes after injection of a toxin targeting neurons with the neurokinin-1 receptor in the nucleus tractus solitarii of rat. J Chem Neuroanat doi:10.1016/j.jchemneu.2012.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Madden CJ, Sved AF (2003) Cardiovascular regulation after destruction of the C1 cell group of the rostral ventrolateral medulla in rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285:H2734–H2748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden CJ, Ito S, Rinaman L, Wiley RG, Sved AF (1999) Lesions of the C1 catecholaminergic neurons of the ventrolateral medulla in rats using anti-DbetaH-saporin. Am J Physiol 277:R1063–R1075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massari VJ, Shirahata M, Johnson TA, Gatti PJ (1996) Carotid sinus nerve terminals which are tyrosine hydroxylase immunoreactive are found in the commissural nucleus of the tractus solitarius. J Neurocytol 25:197–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan MA, Reis DJ (1977) Chronic labile hypertension produced by lesions of the nucleus tractus solitarii in the cat. Circ Res 40:72–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council (1996) Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. National Academy Press, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- Nayate A, Moore SA, Weiss R, Taktakishvili O, Lin L-H, Talman WT (2008) Cardiac damage after lesions of the nucleus tractus solitarii. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 296:R272–R279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley J, Lin L-H, Chianca DA Jr, Talman WT (2002) Ablation of NK1 receptors in rat nucleus tractus solitarii blocks baroreflexes. Hypertension 40:823–826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinaman L (2003) Hindbrain noradrenergic lesions attenuate anorexia and alter central cFos expression in rats after gastric viscerosensory stimulation. J Neurosci 23:10084–10092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder DW, Nathan MA, Reis DJ (1978) Chronic lability of arterial pressure produced by selective destruction of the catecholamine innervation of the nucleus tractus solitarii in the rat. Circ Res 43:662–671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stauss H, Moffitt JA, Chapleau MW, Abboud FM, Johnson AK (2006) Baroreceptor reflex sensitivity estimated by the sequence technique is reliable in rats. Am J Physiol 291(1): H482–H483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talman WT, Kelkar P (1993) Neural control of the heart. Neurol Clin 11:239–255 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talman WT, Snyder DW, Reis DJ (1980) Chronic lability of arterial pressure produced by destruction of A2 catecholaminergic neurons in rat brainstem. Circ Res 46:842–853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]