Abstract

Biomaterial designs are increasingly incorporating multiple instructive signals to induce a desired cell response. However, many approaches do not allow orthogonal manipulation of immobilized growth factor signals and matrix stiffness. Further, few methods support patterning of biomolecular signals across a biomaterial in a spatially-selective manner. Here, we report a sequential approach employing carbodiimide crosslinking and benzophenone photoimmobilization chemistries to orthogonally modify the stiffness and immobilized growth factor content of a model collagen-GAG (CG) biomaterial. We subsequently examined the singular and combined effects of bone morphogenetic protein (BMP-2), platelet derived growth factor (PDGF-BB), and CG membrane stiffness on the bioactivity and osteogenic/adipogenic lineage-specific gene expression of adipose derived stem cells, an increasingly popular cell source for regenerative medicine studies. We found that the stiffest substrates direct osteogenic lineage commitment of ASCs regardless of the presence or absence of growth factors, while softer substrates require biochemical cues to direct cell fate. We subsequently describe the use of this approach to create overlapping patterns of growth factors across a single substrate. These results highlight the need for versatile approaches to selectively manipulate the biomaterial microenvironment to identify synergies between biochemical and mechanical cues for a range of regenerative medicine applications.

Keywords: Mechanical properties, Growth factors, Mesenchymal stem cell, Osteogenesis, Photolithography, Surface modification

1. Introduction

The development of biomaterial tools for a range of tissue engineering applications increasingly relies on the coordinated presentation of multiple instructive signals. These efforts are often inspired by the native extracellular matrix (ECM), where cells receive cues from an assortment of solution phase [1–9] and substrate-supported stimuli [10–15]. The ECM is a complex biomolecular network secreted by cells that serves as a mechanical and structural support within which biomolecular cues can be presented in spatially [16–19] and temporally [20,21] defined manners. Given the regulatory role played by the ECM in a multitude of important processes such as tissue development [22] and repair [19,23], it is not surprising biomaterials platforms are increasingly trying to regulate the coordinated presentation of multiple classes of ECM-inspired signals. However, untangling the interactions between mechanical and biochemical cues is often complicated. New approaches are needed to both elucidate the effects of and then recapitulate the functional properties of such complicated in vivo microenvironments.

In the context of musculoskeletal regeneration, a wide range of studies have concentrated on coordinated presentation of biomolecular signals. Efforts initially focused on presenting a bioactive dose of a given single factors (tenogenesis: IGF-1 [3,24,25], PDGF [9], GDF-5 [26], bFGF [7,27,28]; osteogenesis: BMP-2 [29,30]; angiogenesis: VEGF [31,32]). Our previous work using collagen-GAG biomaterials demonstrated enhanced tenocyte chemotaxis (via IGF-1) and proliferation (via PDGF-BB) in a dose-dependent manner [3]. Moving towards more complex tissue injuries, Thomopoulos et al. demonstrated single factor (BMP-2) supplementation can promote healing at the tendon–bone interface [30]. More recently, efforts have begun to explore the potential of coordinated presentation of multiple cues [1,2,6,8]. Borselli et al. showed a synergistic response in muscle cells with combined delivery of angiogenic and myogenic growth factors [1]. We previously reported advantages of coordinated growth factor presentation for promoting phenotypic stability and proliferation [6], but also found unintended consequences of multi-factor supplementation in the context of MSC-guided regenerative medicine applications [33]. There are often trade-offs in stem cell proliferation and differentiation, which suggests that multiple cues may need to work in tandem to elicit the desired response. Notably, Tan et al. demonstrated that GDF-5 induced tenogenic differentiation in MSCs without negatively impacting proliferation [26], while other studies have looked at multiple cues to promote proliferation (e.g. PDGF) and tenogenesis simultaneously [9,34].

While solution phase supplementation in the media is the most straightforward method to provide instructive biomolecular cues in vitro, it is limited by diffusion and a lack of spatial localization. Inspired by the biomolecular tethering to the native ECM, recent efforts have suggested that immobilized growth factors can enhance bioactivity. A range of methods (e.g., carbodiimide crosslinking [12,29,35], biotin-avidin linkages [36], and ‘click’ chemistries [37]) have recently been reported for covalently attaching growth factors to collagen-based scaffolds. However, these approaches did not include the ability to control the spatial distribution of these biomolecules. In addition, the same crosslinking techniques which are used to immobilize growth factors can also increase biomaterial stiffness. However, biomaterial mechanical properties can have both direct and indirect effects on cell, and particularly MSC, response. The mechanical properties of the matrix are also known to play profound roles impacting cell fate, with a range of stem cells showing particular sensitivity to mechanical stiffness [38–43], making it potentially difficult to assess the individual impact of matrix-immobilized growth factors.

Increasing evidence suggests that mechanical and biomolecular signals may act in a more coordinated manner. Recently Allen et al. reported that matrix stiffness differentially primed the TGFβ signaling pathway in the context of MSC-chondrogenesis [44], suggesting the mechanical stiffness of the environment impacts how sensitive a cell may be to an exogenous factor. Further, Zouani et al. and Tan et al. both demonstrated different types of coordinated responses for MSCs to matrix stiffness and BMP-2 presentation [40,45]. Notably, Zouani et al. demonstrated a minimum stiffness (3.5 kPa) for MSCs to be responsive to BMP-2 with no synergy between matrix stiffness and BMP-2 dose [40], while Tan et al. reported a synergetic effect of matrix stiffness and BMP-2 [45]; however in this case, matrix stiffness was modified via hydrogel density, which likely significantly altered the microstructural cues presented to the cells. Both of these studies support the contention that MSCs integrate multiple extrinsic signals in the context of fate decisions [46–48]. However, these reports also motivate the development of new classes of biomaterials able to orthogonally modify matrix structure, stiffness, and biomolecule incorporation, as well as approaches that are amenable to spatial control over biomolecule incorporation, in order to better control stem cell differentiation and proliferation. Such platforms offer unique potential for the field of tissue engineering and regenerative medicine to more efficiently and effectively utilize structural, mechanical, and biomolecular signals that have yet to be fully realized.

Herein we report a strategy that allows for independent manipulation of the mechanical properties and spatially controlled presentation of biomolecular cues using a collagen-GAG (CG) biomaterial platform. CG biomaterials have been used for a range of soft (e.g., skin, peripheral nerve) [49–51] and hard/musculoskeletal (e.g., bone, cartilage, tendon) [52–54] tissue engineering applications, making them an attractive target for technologies to selectively incorporate exogenous biomolecular signals. We have recently demonstrated approaches to orthogonally modify the microstructural [3] and mechanical [55] properties of, as well as approaches to transiently [20] or covalently [6,56] modify growth factor presentation within these CG biomaterials. Here we build on a previously reported benzophenone (BP) photolithography approach to spatially control immobilization of biomolecules to a CG biomaterial [57]. In this work, we explore the integration of a separate crosslinking approach to allow orthogonal manipulation of matrix stiffness of the density of immobilized biomolecular signals (BMP-2, PDGF-BB). We subsequently describe the individual and combined impacts of matrix mechanical (elastic modulus) cues and immobilized BMP-2/PDGF-BB growth factors on adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cell (ASC) bioactivity. This combined technological approach provides an enabling platform to map synergies between multiple biochemical and mechanical cues across a single biomaterial platform for a range of tissue engineering applications.

2. Materials and methods

All reagents were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise noted. Phosphate buffered saline buffer (PBS) was reconstituted and pH adjusted to 7.4.

2.1. Preparation of CG membranes

CG membranes were prepared via a previously described evaporative process [58,59]. Briefly, a CG suspension was prepared from type I collagen (1.0% w/v) isolated from bovine Achilles tendon and chondroitin sulfate (0.1% w/v) derived from shark cartilage in 0.05 m acetic acid. The suspension was homogenized at 4 °C to prevent collagen gelatinization during mixing [49]. The CG suspension was degassed, pipetted into a petri dish, and allowed to evaporate under ambient conditions to produce a film. Circular membrane specimens (8 mm dia.) were cut using a biopsy punch (Integra-Miltex, York, PA) and stored in a desiccator until use.

2.2. Chemical crosslinking of CG membranes to modulate stiffness

Prior to use, CG membranes were hydrated in ethanol followed by PBS. They were subsequently crosslinked using carbodiimide chemistry [35,55] for 1 h in a solution of 1-ethyl-3-[3–dimethylaminopropyl]carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC) and N-hydroxysulfosuccinimide (NHS) at molar ratios of 1:1:5, 5:2:5, 5:20.7:1, 5:2:1 EDC:NHS:COOH where COOH represents the amount of collagen in the scaffold [35,55]. A control group of membranes were not crosslinked (NX). After crosslinking, membranes were rinsed and stored in PBS until further use.

2.3. Covalent immobilization of growth factors via benzophenone photolithography

Benzophenone (BP) was immobilized to the CG membrane using a previously described approach [57,60]. Briefly, benzophenone-4-isothiocyanate was synthesized as previously reported [61] and dissolved in dimethyl formamide (DMF) to a final concentration of 20mm. To that solution, N,N-diisopropylethylamine was added to a final concentration of 0.5 m. CG membranes were submerged in this solution and allowed to react for 48 h protected from light. Membranes were then rinsed in DMF, ethanol, and PBS to remove unreacted benzophenone reagent, and subsequently stored in PBS at 4 °C in the dark until use [57].

2.4. Biomolecular photoimmobilization

Stock solutions of bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP-2, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and platelet derived growth factor BB (PDGF-BB, R&D Systems) were prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions and stored at −20 °C until use. In preparation for patterning, CG membranes were soaked in a solution containing 5 µg/mL protein (PDGF-BB or BMP-2) in PBS. Membranes were subsequently transferred to a glass slide, covered with a glass coverslip, and exposed to 20 mW/cm2 of ~365 nm light provided by a beam of an argon ion laser (Coherent Innova 90–4 with UV optics, Laser Innovations, Santa Paula, CA) that had been expanded and homogenized using refractive beam shaping optics (π-Shaper, Molecular Technologies, Berlin, Germany). Membranes were exposed for a defined time (1 or 5 min). After UV exposure, membranes were rinsed in a solution of 0.2% pluronic F-127 in PBS. For patterning multiple proteins, membranes were further rinsed in PBS then soaked in the second protein solution and subsequently irradiated as described above. After patterning, membranes were stored in PBS at 4 00B0;C until use.

2.5. Fluorescent visualization of biomolecular patterns

In order to visualize biomolecule attachment, membranes containing immobilized proteins were transferred into a solution of 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS to block non-specific antibody binding. A rabbit anti-PDGF-BB antibody (AbCam, Cambridge, MA) was pre-incubated with Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated goat antirabbit IgG (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at a concentration of 1 µg/mL in 1% BSA-PBS. Similarly, a rabbit anti-BMP-2 antibody (AbCam) was pre-incubated with Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen) at a concentration of 1 µg/mL in 1% BSA-PBS. Membranes were placed in the relevant antibody staining solutions overnight at 4 00B0;C, after which they were rinsed for at least 1 h in PBS and visualized using a fluorescence slide scanner (Axon Instruments-Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Total immobilized protein was estimated using a calibration curve generated from known concentrations of factor [57,62].

2.6. Mechanical characterization

Tensile mechanical tests were performed on hydrated CG membranes (10 mm gauge length × 6 mm wide; 0.6 mm thickness) at a rate of 1.0 mm/min using a Bose Electroforce BioDynamic 5110 with a 1000 g load cell. Data was collected with Bose WinTest software. The elastic modulus was calculated from the linear region of the stress–strain curve for each sample.

2.7. Culture of adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells and CG membrane seeding

ASCs were isolated according to published procedures [63] and stored in liquid nitrogen until use. Two million ASCs were thawed and plated in 75 cm2 tissue culture flasks at a density of 6000 to 7000 cells/cm2 containing high glucose Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin g-streptomycin, and 5.0 mg/L amphotericin b. Cells were expanded at 37 °C and 5% CO2, with the culture medium changed every 3 days. Cells were rinsed with PBS and harvested using 0.25% trypsin-EDTA followed by addition of an equal volume of complete medium. ASCs were centrifuged at 200 g for 5 min and resuspended to a concentration of 1 × 105 cells per 20 µL in DMEM. Cells were seeded onto the CG membranes using a previously described static seeding method [3]. Briefly 10 µL of cell-laden media was pipetted onto one side of each CG membrane in ultra-low attachment 6-well plates (Corning Life Sciences, Lowell, MA) and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 30 min. Membranes were flipped and the remaining 10 µL of cells was added to the membrane. After 30 min of incubation at 37 °C to allow cell attachment, 5 mL of complete DMEM was added to each well. The culture medium was changed every 3 days.

2.8. Quantifying cell attachment and proliferation

Total number of cells attached to the CG membranes were monitored using Hoechst 33,258 dye (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) which fluorescently labels double-stranded DNA [64]. Total cell number was determined at day 0 (initial cell attachment) as well as days 1, 4 and 7 (subsequent proliferation) using a fluorescence spectrophotometer (Tecan Group Ltd., Männedorf, Switzerland)

2.9. Characterizing cell bioactivity

The mitochondrial metabolic activity of ASCs seeded on the CG membranes were quantified via alamarBlue® (Invitrogen) [65]. Membranes were incubated in the alamarBlue solution with gentle shaking for 1 h. Viable cells reduce the resazurin in the alamarBlue solution to resorufin, which produces fluorescence. Fluorescence was measured (excitation 540 nm, emission 580 nm) on a fluorescent spectrophotometer (Tecan). Results were compared to a prepared standard to compute equivalent cell number. Results (n = 3/timepoint) were reported as the relative metabolic activity compared to the number of originally seeded cells.

2.10. RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis, and quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction

The expression of osteogenic, adipogenic, and matrix synthesis markers was determined via qPCR using previously described methods [52,66]. Membranes were rinsed in PBS to remove unattached cells. Total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy plant kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA) and converted to cDNA using a QuantiTect reverse transcription kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA), both according to the manufacturer's instructions. Gene expression profiles were determined for alkaline phosphatase (ALP), type 1 collagen alpha-1 (COL1A1), osteocalcin (OCN), and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARG), with glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) used as a housekeeping gene. Previously validated primer sequences were chosen from the literature (Table 1) and purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coraville, IA). Gene expression profiles were determined via three independent replicates of each experimental condition by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR). qRT-PCR was performed using a 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The cDNA was amplified according to the following conditions: 50 °C for 2 min and 95 °C for 10 min, then 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 60 s for 40 amplification cycles. Amplification was monitored by SYBR Green and a dissociation melting curve was performed to confirm a single PCR product. Results were analyzed using SDS Software and the transcripts of interest were normalized to the housekeeping gene GAPDH. Relative fold change (foldΔ) was calculated using the delta–delta Ct method.

Table 1.

Primer sequences used for qPCR.

| Name | Forward primer (5′-3′) | Reverse primer (5′-3′) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| COL1A1 | AGAAGAAGACATCCCACCAGTCA | CCGTTGTCGCAGACACAGAT | [63] |

| OCNa | GAGGGAGGTGTGTGAGCTCAA | GGCTGCGAGGTCTAGGCTATG | [63] |

| ALP | CCCTTCACTGCCATCCTGTAC | GGTAGTTGTCGTGCGCATAGTC | [63] |

| PPARG | GAGCCCAAGTTCGAGTTTGC | GGCGGTCTCCACTGAGAATAAT | [63] |

| GAPDH | GTCAAGCTCATTTCCTCGTACGA | CTCTTACTCCTTGGAGGCCA | [63] |

Also known as bone gamma-carboxyglutamic acid-containing protein (BGLAP).

2.11. Statistical analysis

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed on biomolecular immobilization data (Fig. 1B–C), tensile mechanical properties (Fig. 2), and orthogonal control of biomolecular presentation and CG membrane stiffness (Fig. 3), followed by Tukey's post-hoc test. Two-way ANOVA was performed on all other data sets followed by a Tukey post-hoc test. Independent factors included crosslinking and immobilized growth factor (PDGF-BB, BMP-2). Pairwise comparisons were performed as necessary. Mechanical characterization used at least n = 7 membranes per group while cell number, metabolic activity and gene expression experiments used n = 3 membranes per group, estimation of biomolecule immobilization as a function of exposure time used n = 4 membranes per group, while biomolecule immobilization as a function of EDC crosslinking used n = 10 membranes per group. Significance was set at p < 0.05. Error bars are reported as standard error of the mean unless otherwise noted.

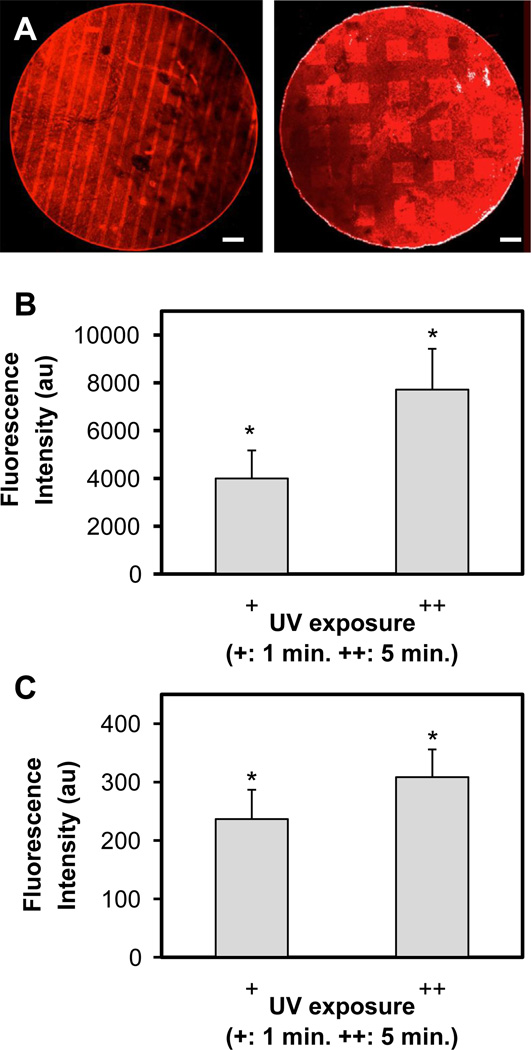

Fig. 1.

(A) Representative image of photoimmobilized PDGF (stripe) and BMP-2 (square) on CG membranes. Scale bar: 500 µm. (B) Immobilization of PDGF-BB as a function of UV exposure time (1, 5 min) normalized versus non-irradiated control. (C) Immobilization of BMP-2 as a function of UV exposure time (1, 5 min) normalized versus non-irradiated control.*: significant increase versus non-irradiated control.

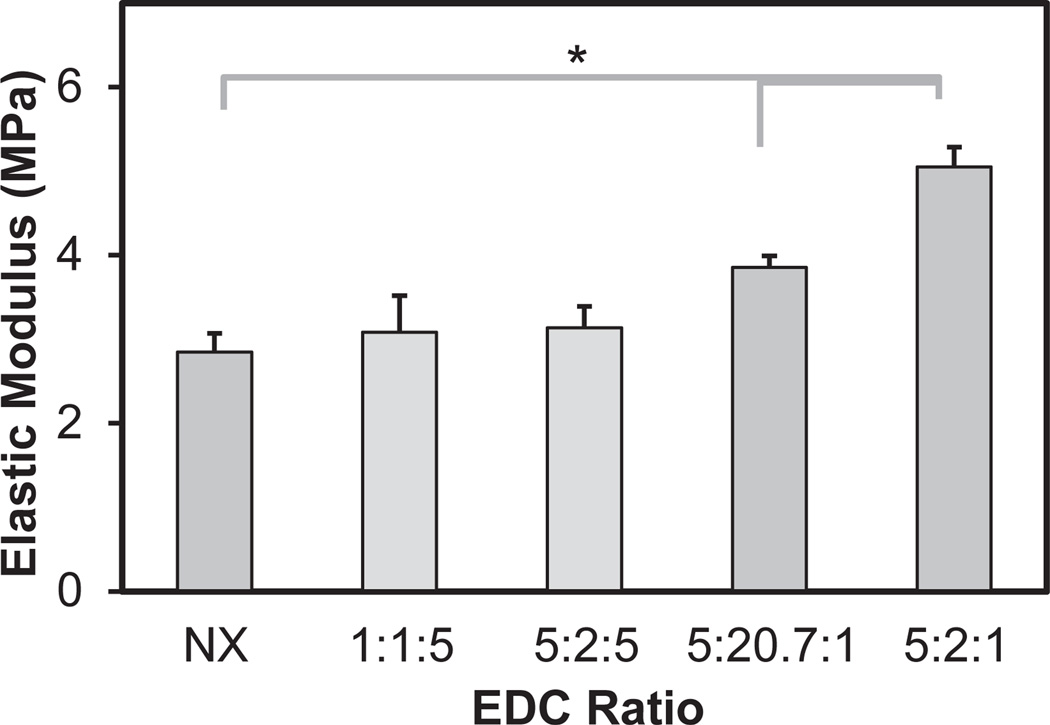

Fig. 2.

Elastic modulus of crosslinked CG membranes as a function of EDC:NHS crosslinking intensity. *: significant difference between groups.

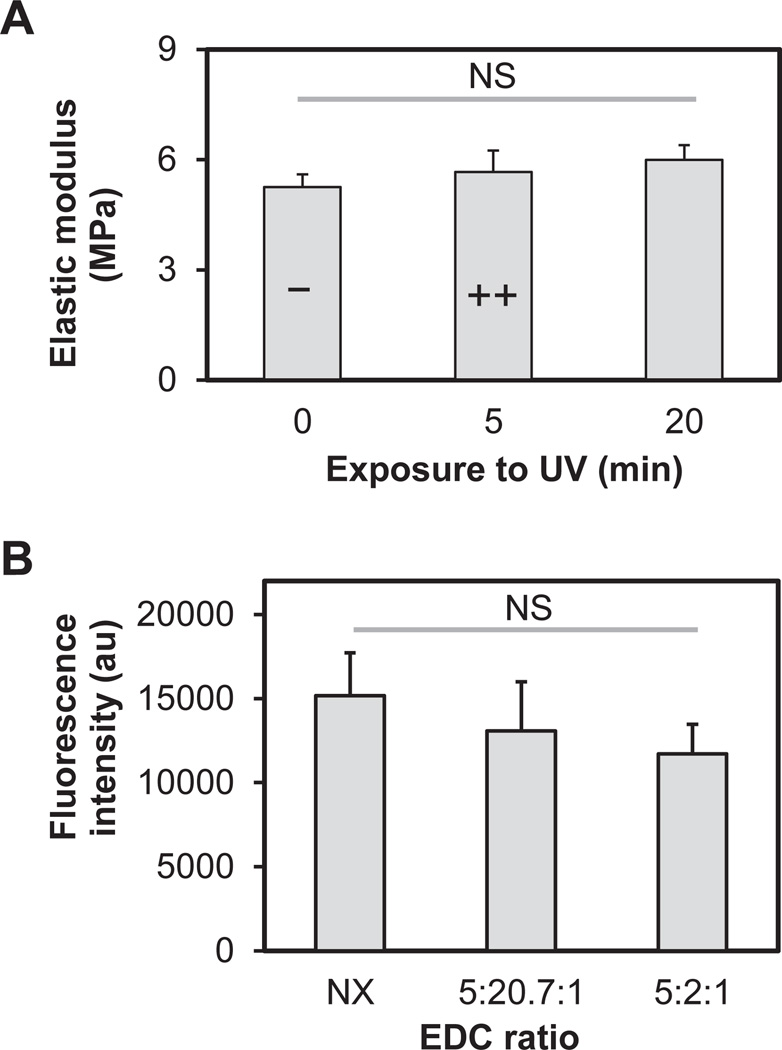

Fig. 3.

Orthogonal control of biomolecular patterning and CG membrane stiffness. (A) Elastic modulus of CG membranes as a function of UV exposure. (B) Mean fluorescence intensity of photoimmobilized PDGF (UV: 5 min) as a function of EDC crosslinking intensity. Results reported as mean ± standard deviation.

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of functional patterns of growth factors on CG membranes

Both BMP-2 and PDGF-BB were successfully immobilized on CG membranes, either in discrete patterns of stripes or squares (Fig. 1A). Increasing the UV exposure time (+: 1 min; ++: 5 min) resulted in significant (p < 0.05) increase in immobilization of both PDGF-BB (Fig. 1B) and BMP-2 (Fig. 1C) versus no UV exposure. Total immobilized protein within exposed areas was determined for PDGF (+: 0.03 ng/mm2; ++: 0.05 ng/mm2) and BMP-2 (++: 0.10 ng/mm2).

Further, while only one side of the CG membrane was directly exposed to UV light during photoimmobilization, identical biomolecular patterns were observed on both sides (Supplementary Fig. 1). Therefore for all subsequent bioactivity assays, cells were seeded on both sides of the membranes after BP-photopatterning.

3.2. Mechanical properties of crosslinked CG membranes

CG membranes were crosslinked using a range of carbodiimide crosslinking intensities. Increasing the EDC:NHS:COOH crosslinking ratio (NX: non-crosslinked; 1:1:5; 5:2:5; 5:20.7:1; 5:2:1) led to a significant (p < 0.05) increase in membrane stiffness. Here, three crosslinking chemistries (NX; 5:20.7:1; 5:2:1) were identified that led to significant (p < 0.001) differences in membrane stiffness (2.85 ± 0.22, 3.86 ± 0.14, 5.05 ± 0.24 MPa) between all groups (Fig. 2).

3.3. Orthogonal control of biomolecular patterning and CG membrane stiffness

To confirm the capacity to orthogonally manipulate mechanical stiffness and immobilized biomolecules, we assessed the coordinated changes of EDC crosslinking and BP photoimmobilization. Notably, while UV exposure has been used to crosslink collagen biomaterials, increasing UV exposure (even to the level of 20 min, far beyond the maximal 5 min exposure used for BP photoimmobilization) did not impact EDC crosslinked membrane stiffness (Fig. 3A). Further, increasing EDC crosslinking did not impact BP photoimmobilization (Fig. 3B). Together, these suggest orthogonal control of biomolecular patterning and CG membrane stiffness for the range of stiffness and biomolecular pattern densities reported here.

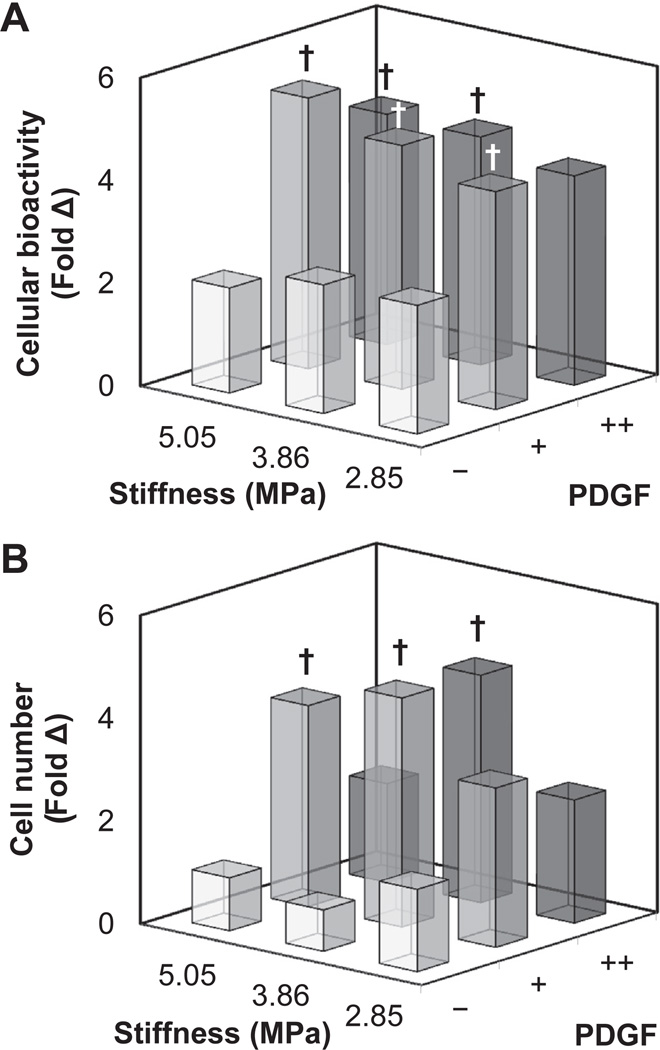

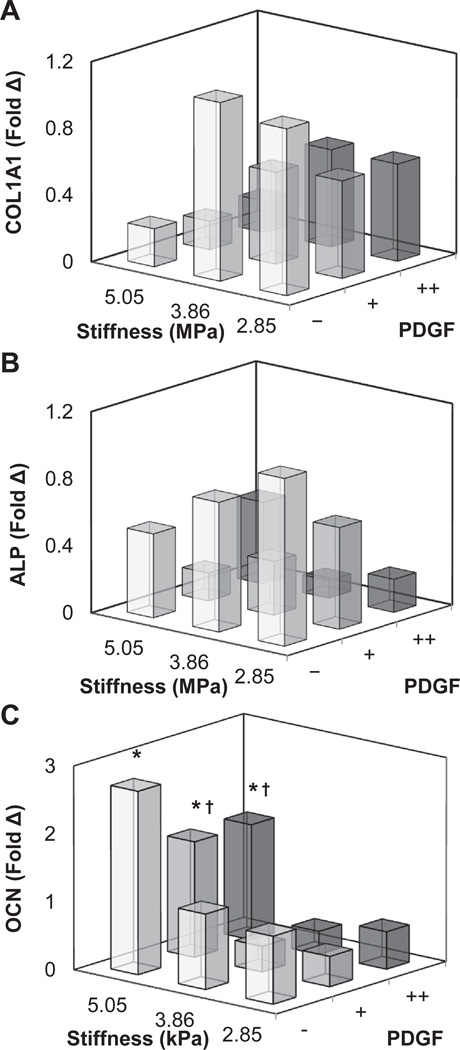

3.4. Cellular bioactivity and gene expression on CG membranes patterned with PDGF

We then explored the coordinated impact of substrate stiffness (2.85, 3.86, 5.05 MPa) and immobilized PDGF (−, +, ++) on the proliferation and metabolic activity (Fig. 4; Supplementary Fig. 2) as well as changes in osteogenic gene expression profile (Fig. 5; Supplementary Fig. 3) of ASCs. Notably, ASC metabolic activity was significantly (p < 0.001) impacted by immobilized PDGF regardless of membrane stiffness (Fig. 4A). Here ASC showed an approximately 2-fold increase in metabolic activity by day 7 in the presence of photoimmobilized PDGF, but showed no response to changes in matrix stiffness. ASC proliferation showed similar response (Fig. 4B). Two-way ANOVA suggested significant (p < 0.05) interaction between matrix stiffness and PDGF immobilization, though comparison between all groups identified a significant (p < 0.001) influence of immobilized PDGF on ASC proliferation. The greatest increase in cell number was on moderately stiff membranes, suggesting an optimal stiffness for cell proliferation (Fig. 4B). Examining gene expression profiles of the ASCs, more complex relationships between matrix stiffness and immobilized PDGF appeared (Fig. 5). Expression of type I collagen alpha-1 (COL1A1; Fig. 5A) was significantly (p < 0.05) downregulated with increasing stiffness and increasing PDGF immobilization, while alkaline phosphatase (ALP; Fig. 5B) was significantly (p < 0.05) downregulated only with increasing PDGF immobilization. Comparatively, osteocalcin (OCN; Fig. 5C) expression was significantly (p < 0.001) upregulated with matrix stiffness, but significantly (p < 0.001) downregulated with increasing PDGF immobilization. However, no interactions were observed between matrix stiffness and immobilized PDGF.

Fig. 4.

(A) ASC metabolic bioactivity and (B) overall cell number at day 7 on CG membranes as a function of substrate stiffness and photoimmobilized PDGF. †: significant increase compared to non-PDGF functionalized substrate of identical stiffness. Individual comparisons (substrate stiffness, PDGF immobilization) between all groups are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2.

Fig. 5.

Gene expression profiles of (A) collagen 1 (COL1A1), (B) alkaline phosphatase (ALP), and (C) osteocalcin (OCN) for ASCs cultured on CG substrates as a function of stiffness and photoimmobilized PDGF. *: significant increase compared to softest substrate with identical immobilized protein concentration. †: significant downregulation compared to non-PDGF functionalized substrate of identical stiffness. Individual comparisons (substrate stiffness, PDGF immobilization) between all groups are shown in Supplementary Fig. 3.

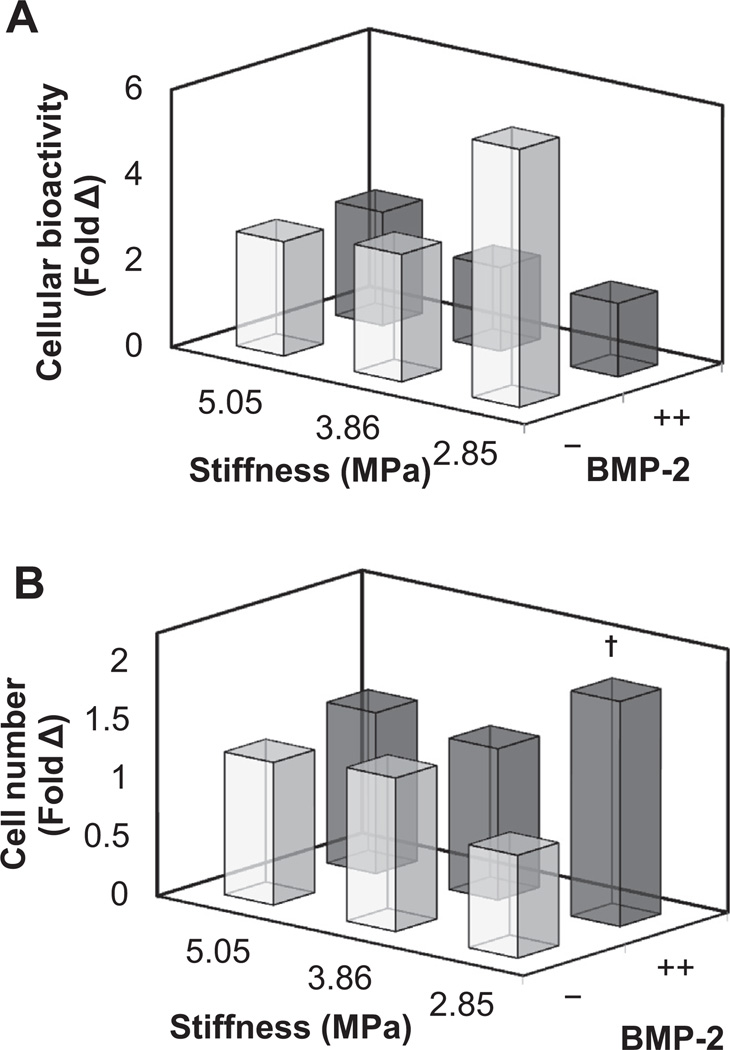

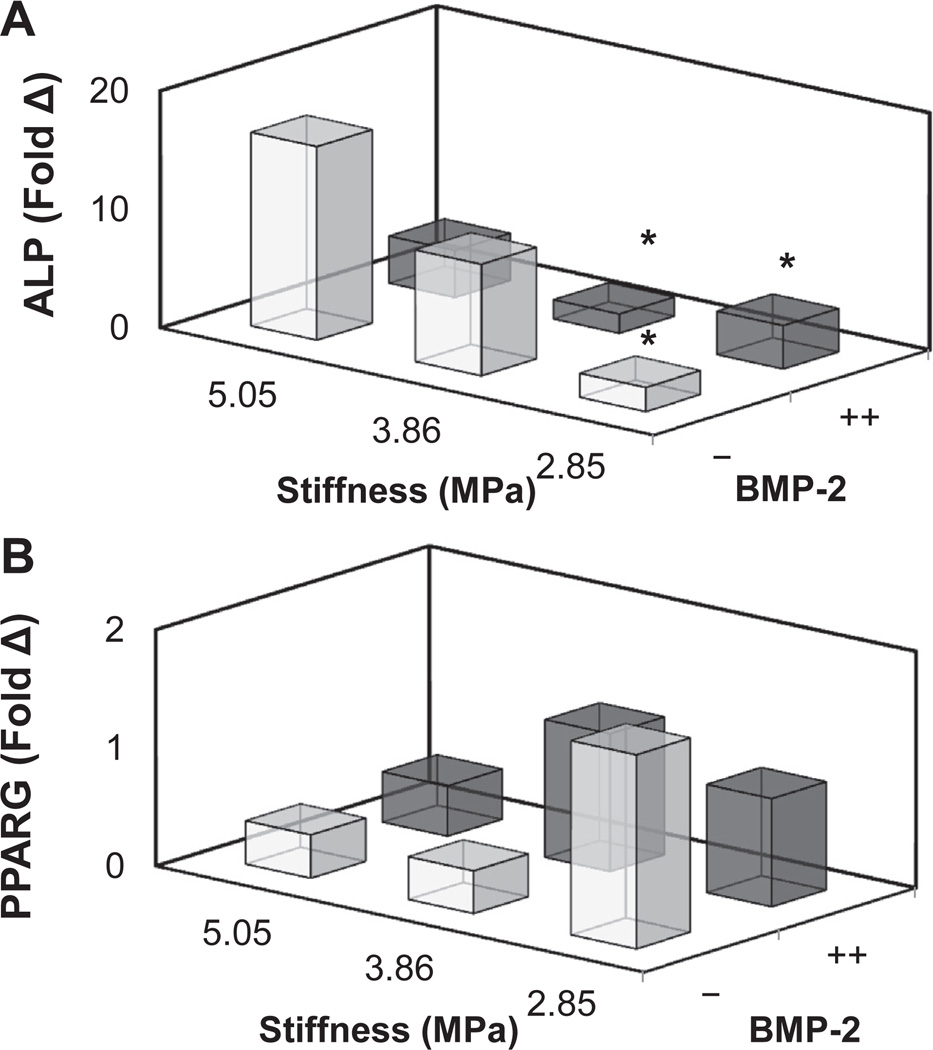

3.5. Cellular bioactivity and gene expression on CG membranes patterned with BMP-2

We then examined the coordinated impact of substrate stiffness (2.85, 3.86, 5.05 MPa) and immobilized BMP-2 (−,++) on the proliferation and metabolic activity (Fig. 6; Supplementary Fig. 4) as well as changes in osteogenic gene expression profile (Fig. 7; Supplementary Fig. 5) of ASCs. The metabolic activity and total number of ASCs was not impacted by either substrate stiffness or immobilized BMP-2, with the exception of a significant (p < 0.05) increase in ASC number with BMP-2 on the softest substrate (Fig. 6B). In addition, ASCs showed a significant (p < 0.05) upregulation in the osteogenic marker alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and a decrease in the adipogenicmarker peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARG) with substrate stiffness, regardless of BMP-2 immobilization (Fig. 7A).

Fig. 6.

(A) ASC metabolic bioactivity and (B) overall cell number at day 7 on CG membranes as a function of substrate stiffness and photoimmobilized BMP-2. †: significant difference compared to substrate of equal stiffness but without BMP-2. Individual comparisons (substrate stiffness, BMP-2 immobilization) between all groups are shown in Supplementary Fig. 4.

Fig. 7.

Gene expression profiles of ASCs cultured on CG substrates as a function of stiffness and photoimmobilized BMP-2. (A) Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) expression is upregulated with substrate stiffness. *: significant decrease relative to stiffest membrane with no protein. (B) Adipogenic peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARG) expression decreases with increasing substrate stiffness. Individual comparisons (substrate stiffness, BMP-2 immobilization) between all groups are shown in Supplementary Fig. 5.

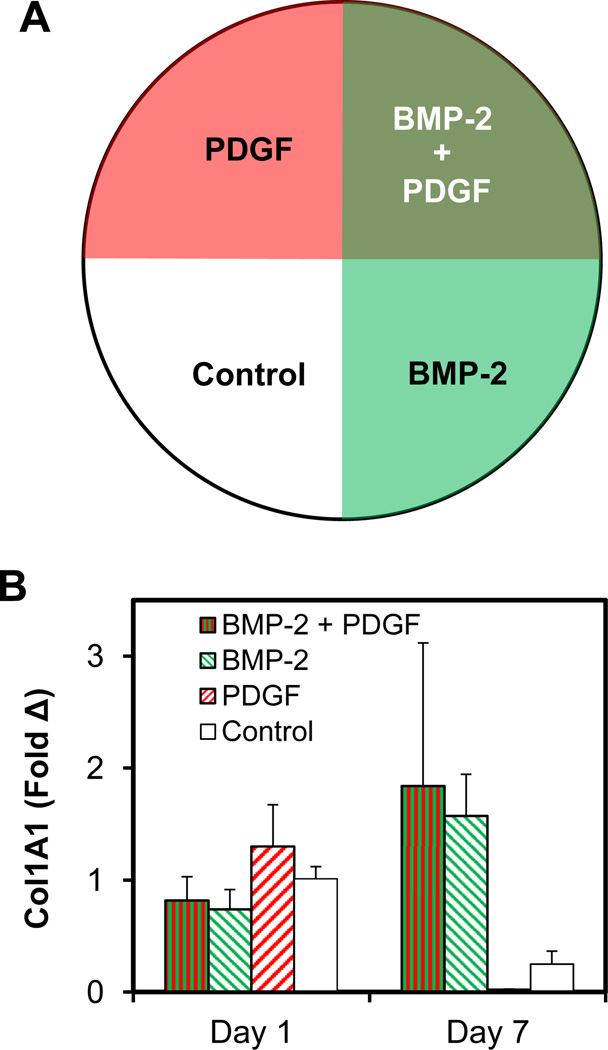

3.6. Gene expression on membranes patterned in quadrants of PDGF and BMP-2

We subsequently examined the interaction between BMP-2 and PDGF, creating variants of CG membranes by sequentially immobilizing half the membrane with BMP-2, rotating the membrane 90°, then photoimmobilizing PDGF to create a single substrate with all possible protein combinations in 4 quadrants (BMP-2/PDGF, BMP-2 only, PDGF only, no factor; Fig. 8A). Region-specific differences in collagen 1 were observed (Fig. 8B). Confirming observations using monolithic patterns (Fig. 5), collagen 1 expression was downregulated with photoimmobilized PDGF (Fig. 8B). However, photoimmobilized BMP-2 was sufficient to both increase collagen 1 expression when presented alone as well as to rescue collagen 1 expression in the presence of PDGF and BMP-2 (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8.

(A) Schematic of 4-quadrant overlapping pattern of PDGF and BMP-2 generated on CG membranes. (B) Gene expression levels of collagen 1 (COL1A1) normalized versus ASCs on control substrates (−/−).

4. Discussion

This work describes the development of a collagen-GAG membrane platform that enables independent manipulation of mechanical properties and biomolecule immobilization as well as spatial control over the location of biomolecule immobilization. It has been increasingly recognized that mechanical, structural, and biochemical cues all impact cell bioactivity This constellation of substrate properties has the potential to act synergistically or destructively, or may differentially prime cell response to other signals, making strategies to orthogonally control these cues an important design target. However, orchestrated control of these properties is challenging. Many studies have focused on controlling only one property at a time, such as PDGF to induce cell proliferation [9,67–69], BMP-2 to promote a pro-osteogenic phenotype [29,70,71], or the use of IGF-1 [24] or TGFβ [72–74] to promote a pro-tenogenic phenotype. And while some recent approaches have begun to explore the combinatorial effects of matrix stiffness and biomolecular signals [40,44,45], strategies to incorporate spatial control over biomolecular signals remains poorly developed.

In this work we describe integration of carbodiimide crosslinking and benzophenone photolithography methods to investigate independent and combined effects of biophysical signals (stiffness) and multiple biomolecular cues (BMP-2, PDGF-BB) on porcine adipose derived stem cells using a model collagen-GAG biomaterial. We have previously reported the utility of benzophenone-based biomolecule immobilization [60]within the collagen-GAG biomaterial platform [57] as well as on glass [62,75–77], and have also demonstrated that photoimmobilized biomolecules retain their activity; however, we had not explored the potential of BP-photolithography to facilitate orthogonal manipulation of matrix stiffness and growth factor immobilization. In this study, PDGF and BMP-2 were chosen as model growth factors due to their known potential to impact cell proliferation [6,9] and osteogenesis [29,45,53], respectively. While tracking proliferation and gene expression profiles of porcine adipose derived stem cells is well defined [63], the relative impact of PDGF and BMP-2 on these processes remained unknown.

We first demonstrated that both factors could be covalently immobilized to the CG membrane in defined patterns, and that these patterns extended through the depth of the membranes (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 1). We subsequently demonstrated the utility of a combined photolithography-carbodiimide crosslinking strategy to orthogonally manipulate matrix stiffness and biomolecule immobilization. Similar to previous observations [54,55,78], increasing EDC:NHS:COOH ratios increased collagen-GAG stiffness. Here we identified 3 crosslinking treatments (Fig. 2) and created substrates with significantly different elastic moduli. Crosslinking treatments were chosen so that all substrate were kept in a closely related range of stiffness (2.85–5 MPa). Importantly, UV exposure during BP photolithography did not significantly impact mechanical properties of the membranes and EDC crosslinking did not impact later surface bioconjugation (Fig. 3). Previously, we demonstrated that BP photoimmobilization does not impact the crystallinity or structural properties of the collagen fibers within the CG biomaterial [57]. Together, these results suggest that sequential use of EDC-crosslinking and BP-photolithography provides a platform to orthogonally manipulate the elastic modulus and presence of immobilized biomolecules within a model CG biomaterial.

We subsequently investigated the individual and coordinated impact of matrix stiffness and biomolecule (PDGF, BMP-2) attachment on adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cell bioactivity (Figs. 4–7). While many of these results are consistent with previous findings in the literature that investigated the monolithic impact of PDGF [3,6,9,79], BMP-2 [29,30], or matrix stiffness [38,40], results reported here serve as an important proof-of-principle of a coordinated approach to examine the intersection between mechanical and biomolecular signals. We observed significantly increased metabolic activity and cell proliferation on substrates with low and high doses of immobilized PDGF as compared to controls (Fig. 4). We also found that matrix stiffness contributed to cell proliferation, which peaked at intermediate substrate stiffness at the highest dose of PDGF. Matrix stiffness has previously been shown to increase growth-factor-dependent Erk activation through focal adhesion assembly [80], providing an explanation for our observed differential response in PDGF-induced proliferation. The facile identification of a combination of PDGF density and substrate stiffness to increase proliferation highlights the potential of our approach. Similar to our previous observations of examining tenocyte bioactivity in response to PDGF supplementation [6], there appeared to be a tradeoff between cell proliferation and phenotype with PDGF supplementation (Fig. 5). While COL1A1, ALP, and OCN expression were all upregulated with increasing stiffness, this effect was lost with addition of the pro-growth signal, PDGF (Fig. 5). We subsequently examined the effects of BMP-2 immobilization and matrix stiffness on ASC bioactivity and gene expression. To simplify analysis, we chose to examine the presence/absence of photoimmobilized BMP-2 rather than dose-dependent results. Consistent with previous findings in the literature [79,81], we found cell bioactivity was not correlated with BMP-2, and additionally noted a lack of coordinated interaction between BMP-2 and substrate stiffness (Fig. 6). Although BMP-2 is a known pro-osteogenic factor, we observed that photoimmobilized BMP-2 had little effect on lineage-specific gene expression. Instead, stiffness had a major effect on ASCs which exhibited increasing pro-osteogenic ALP expression and decreasing pro-adipogenic PPARG expression with increasing substrate stiffness (Fig. 7). The impact of matrix stiffness on changes in pro-osteogenic vs. pro-adipogenic gene expression profiles is consistent with previous observations in the literature [82]. While initially surprising, the lack of an effect of BMP-2 on pro-osteogenic gene expression profiles suggest that over the range of stiffness and BMP-2 density tested here, ASC response is dominated by matrix mechanical properties. Ongoing efforts are exploring a wider range of matrix stiffness and immobilized BMP-2 densities. Further, as BP photoimmobilization has been shown to be effective within fully-3D CG scaffolds, future efforts will likely explore the coordinated impact of matrix stiffness, pore size, and BMP-2 immobilization in the context of regenerative medicine approaches for critical size bone defects.

To demonstrate the greater potential for integrating BP photolithography with the CG biomaterial platform, we lastly examined spatially-defined interactions between PDGF and BMP-2 (Fig. 8). Such an effort is a demonstration of principle for ongoing efforts exploring a wider range of pattern densities and their resultant impact on ASC response. Here, we examine the impact of the highest immobilization density of both PDGF and BMP-2 on the substrate with the greatest stiffness. No significant difference in metabolic activity or cell number was observed after 7 days (data not shown); however, expression of COL1A1was strongly increased with the presence of BMP-2 alone or in combination with PDGF (Fig. 8). Substrates containing PDGF alone, or no immobilized growth factors, showed marked downregulation of COL1A1, consistent with observations for monolithic PDGF immobilization (Fig. 5). Given the observed interactions between matrix stiffness and biomolecule immobilization, future efforts will leverage this approach to explore a wider range of combinatorial environments. Further, given recent observations that matrix stiffness can impact MSC receptivity to biomolecular signals [44], the system described here may offer unique potential to rapidly assess signal transduction and cell response for a range of matrix environments across a single substrate via immunofluorescence-based assays. Here, efficient identification of combinations of matrix mechanical and biomolecular signals able to support enhanced ASC bioactivity in the absence of media supplementation provides the foundation for developing instructive biomaterials containing selective alterations to mechanical and compositional properties to enhance multi-lineage ASC specification in a spatially-selective manner.

5. Conclusions

This work establishes the ability to separate fabrication and biomolecule patterning via a molecularly-general biomolecule photoimmobilization method using a CG biomaterial. We demonstrated sequential use of carbodiimide crosslinking and benzophenone photoimmobilization chemistries to independently control immobilization of multiple biomolecular species (PDGF, BMP-2) as well as the mechanical properties of a model CG substrate. Notably, this approach allows us to identify the coordinated impact of mechanical and biochemical cues on ASC metabolic activity, proliferation, and gene expression profile. Overall, our results highlight how the bioactivity and lineage commitment of adipose stem cells depend on a variety of cues whose optimal combinations are difficult to predict. The approach described here may prove particularly valuable for high throughput screening of biomaterials to identify environments supportive of a range of stem cell phenotypes. Given the certain complexity of the chemical and mechanical environments that determine stem cell fate and lineage commitment, this capability to independently control both classes of cue presentation should enable more facile engineering of customized scaffold materials applicable to a wide range of tissue engineering goals. These efforts are informing ongoing work in our lab to enhance the regenerative potential of spatially-gradated CG scaffolds for regenerative repair of orthopedic insertions such as the osteotendinous junction.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Amy Wagoner Johnson (UIUC) for access to the tensile mechanical testing equipment as well as Dr. Michael Poellman for assistance with mechanical testing. Porcine adipose derived stem cells were a gift from Dr. Mathew Wheeler (UIUC). We would also like to thank Aurora Alsop for the synthesizing the benzophenone-4-isothiocyanate and Rebecca Hortensius for helpful discussions. We gratefully acknowledge the funding provided from the National Science Foundation Division of Material Research under award 1105300 (BAH and RCB) and the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation (RCB). Research reported in this publication also was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers R21 AR063331 (BAH). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We also appreciate support provided through the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign's Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering (BAH), Institute for Genomic Biology (BAH), and Materials Research Laboratory (DE-FG02-07ER46453 and DE-FG02-07ER46471). LM was supported through National Science Foundation Grant 0965918 IGERT: Training the Next Generation of Researchers in Cellular and Molecular Mechanics and BioNanotechnology.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data related to this article can http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.07.012.

Contributor Information

Brendan A.C. Harley, Email: bharley@illinois.edu.

Ryan C. Bailey, Email: baileyrc@illinois.edu.

References

- 1.Borselli C, Storrie H, Benesch-Lee F, Shvartsman D, Cezar C, Lichtman JW, et al. Functional muscle regeneration with combined delivery of angiogenesis and myogenesis factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:3287–3292. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903875106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buket Basmanav F, Kose GT, Hasirci V. Sequential growth factor delivery from complexed microspheres for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2008;29:4195–4204. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caliari SR, Harley BAC. The effect of anisotropic collagen-GAG scaffolds and growth factor supplementation on tendon cell recruitment, alignment, and metabolic activity. Biomaterials. 2011;32:5330–5340. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hagerty P, Lee A, Calve S, Lee CA, Vidal M, Baar K. The effect of growth factors on both collagen synthesis and tensile strength of engineered human ligaments. Biomaterials. 2012;33:6355–6361. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.05.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Becerra-Bayona S, Guiza-Arguello V, Qu X, Munoz-Pinto DJ, Hahn MS. Influence of select extracellular matrix proteins on mesenchymal stem cell osteogenic commitment in three-dimensional contexts. Acta Biomater. 2012;8:4397–4404. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.07.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caliari SR, Harley BAC. Composite growth factor supplementation strategies to enhance tenocyte bioactivity in aligned collagen-GAG scaffolds. Tissue Eng Pt A. 2013;19:1100–1112. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2012.0497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan BP, Fu S, Qin L, Lee K, Rolf CG, Chan K. Effects of basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) on early stages of tendon healing: a rat patellar tendon model. Acta Orthop. 2000;71:513–518. doi: 10.1080/000164700317381234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen F-M, Zhang M, Wu Z-F. Toward delivery of multiple growth factors in tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2010;31:6279–6308. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng X, Tsao C, Sylvia VL, Cornet D, Nicolella DP, Bredbenner TL, et al. Platelet-derived growth-factor-releasing aligned collagen–nanoparticle fibers promote the proliferation and tenogenic differentiation of adipose-derived stem cells. Acta Biomater. 2014;10:1360–1369. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kapur TA, Shoichet MS. Immobilized concentration gradients of nerve growth factor guide neurite outgrowth. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2004;68A:235–243. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller ED, Li K, Kanade T, Weiss LE, Walker LM, Campbell PG. Spatially directed guidance of stem cell population migration by immobilized patterns of growth factors. Biomaterials. 2011;32:2775–2785. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Odedra D, Chiu LLY, Shoichet M, Radisic M. Endothelial cells guided by immobilized gradients of vascular endothelial growth factor on porous collagen scaffolds. Acta Biomater. 2011;7:3027–3035. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Culver JC, Hoffmann JC, Poché RA, Slater JH, West JL, Dickinson ME. Three-dimensional biomimetic patterning in hydrogels to guide cellular organization. Adv Mater. 2012;24:2344–2348. doi: 10.1002/adma.201200395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kapoor A, Caporali EHG, Kenis PJA, Stewart MC. Microtopographically patterned surfaces promote the alignment of tenocytes and extracellular collagen. Acta Biomater. 2010;6:2580–2589. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tseng P, Di Carlo D. Substrates with patterned extracellular matrix and subcellular stiffness gradients reveal local biomechanical responses. Adv Mater. 2014;26:1242–1247. doi: 10.1002/adma.201304607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raghavan S, Gilmont RR, Bitar KN. Neuroglial differentiation of adult enteric neuronal progenitor cells as a function of extracellular matrix composition. Biomaterials. 2013;34:6649–6658. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bi Y, Ehirchiou D, Kilts TM, Inkson CA, Embree MC, Sonoyama W, et al. Identification of tendon stem/progenitor cells and the role of the extracellular matrix in their niche. Nat Med. 2007;13:1219–1227. doi: 10.1038/nm1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dobaczewski M, de Haan JJ, Frangogiannis NG. The extracellular matrix modulates fibroblast phenotype and function in the infarcted myocardium. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2012;5:837–847. doi: 10.1007/s12265-012-9406-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dunkman AA, Buckley MR, Mienaltowski MJ, Adams SM, Thomas SJ, Satchell L, et al. The tendon injury response is influenced by decorin and biglycan. Ann Biomed Eng. 2014;42:619–630. doi: 10.1007/s10439-013-0915-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hortensius RA, Harley BA. The use of bioinspired alterations in the glycosaminoglycan content of collagen-GAG scaffolds to regulate cell activity. Biomaterials. 2013;34:7645–7652. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.06.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hempel U, Hintze V, Moller S, Schnabelrauch M, Scharnweber D, Dieter P. Artificial extracellular matrices composed of collagen I and sulfated hyaluronan with adsorbed transforming growth factor beta1 promote collagen synthesis of human mesenchymal stromal cells. Acta Biomater. 2012;8:659–666. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gershlak JR, Resnikoff JI, Sullivan KE, Williams C, Wang RM, Black LD., 3rd Mesenchymal stem cells ability to generate traction stress in response to substrate stiffness is modulated by the changing extracellular matrix composition of the heart during development. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;439:161–166. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.08.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salbach J, Rachner TD, Rauner M, Hempel U, Anderegg U, Franz S, et al. Regenerative potential of glycosaminoglycans for skin and bone. J Mol Med. 2012;90:625–635. doi: 10.1007/s00109-011-0843-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abrahamsson S-O, Lundborg G, Lohmander LS. Recombinant human insulin-like growth factor-I stimulates in vitro matrix synthesis and cell proliferation in rabbit flexor tendon. J Orthop Res. 1991;9:495–502. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100090405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li Y, Yu X, Lin S, Li X, Zhang S, Song Y-H. Insulin-like growth factor 1 enhances the migratory capacity of mesenchymal stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;356:780–784. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tan S-L, Ahmad RE, Ahmad TS, Merican AM, Abbas AA, Ng WM, et al. Effect of growth differentiation factor 5 on the proliferation and tenogenic differentiation potential of human mesenchymal stem cells in vitro. Cells Tissues Organs. 2012;196:325–338. doi: 10.1159/000335693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oryan A, Moshiri A. Recombinant fibroblast growth protein enhances healing ability of experimentally induced tendon injury in vivo. J Tissue Eng Regen M. 2014;8:421–431. doi: 10.1002/term.1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmidt A, Ladage D, Schinköthe T, Klausmann U, Ulrichs C, Klinz F-J, et al. Basic fibroblast growth factor controls migration in human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2006;24:1750–1758. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Madl CM, Mehta M, Duda GN, Heilshorn SC, Mooney DJ. Presentation of BMP-2 mimicking peptides in 3D hydrogels directs cell fate commitment in osteoblasts and mesenchymal stem cells. Biomacromolecules. 2014;15:445–455. doi: 10.1021/bm401726u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomopoulos S, Kim HM, Silva MJ, Ntouvali E, Manning CN, Potter R, et al. Effect of bone morphogenetic protein 2 on tendon-to-bone healing in a canine flexor tendon model. J Orthop Res. 2012;30:1702–1709. doi: 10.1002/jor.22151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Borselli C, Ungaro F, Oliviero O, d'Angelo I, Quaglia F, La Rotonda MI, et al. Bioactivation of collagen matrices through sustained VEGF release from PLGA microspheres. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2010;92A:94–102. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee JS, Wagoner Johnson AJ, Murphy WL. A modular, hydroxyapatite-binding version of vascular endothelial growth factor. Adv Mater. 2010;22:5494–5498. doi: 10.1002/adma.201002970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Caliari SR, Harley BAC. Collagen-GAG scaffold biophysical properties bias MSC lineage choice in the presence of mixed soluble signals. Tissue Eng Pt A. 2014 doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2013.0400. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/ten.tea.2013.0400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park A, Hogan MV, Kesturu GS, James R, Balian G, Chhabra AB. Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells treated with growth differentiation factor-5 express tendon-specific markers. Tissue Eng Pt A. 2010;16:2941–2951. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2009.0710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olde Damink LHH, Dijkstra PJ, Van Luyn MJA, Van Wachem PB, Nieuwenhuis P, Feijen J. Cross-linking of dermal sheep collagen using a water-soluble carbodiimide. Biomaterials. 1996;17:765–773. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(96)81413-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu W-W, Wang Z, Krebsbach PH. Virus immobilization on biomaterial scaffolds through biotin–avidin interaction for improving bone regeneration. J Tissue Eng Regen M. 2013 doi: 10.1002/term.1774. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/term.1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hudalla GA, Murphy WL. Immobilization of peptides with distinct biological activities onto stem cell culture substrates using orthogonal chemistries. Langmuir. 2010;26:6449–6456. doi: 10.1021/la1008208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Engler AJ, Sen S, Sweeney HL, Discher DE. Matrix elasticity directs stem cell lineage specification. Cell. 2006;126:677–689. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Choi JS, Harley BAC. The combined influence of substrate elasticity and ligand density on the viability and biophysical properties of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Biomaterials. 2012;33:4460–4468. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zouani OF, Kalisky J, Ibarboure E, Durrieu M-C. Effect of BMP-2 from matrices of different stiffnesses for the modulation of stem cell fate. Biomaterials. 2013;34:2157–2166. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu B, Song G, Ju Y, Li X, Song Y, Watanabe S. RhoA/ROCK, cytoskeletal dynamics, and focal adhesion kinase are required for mechanical stretchinduced tenogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. J Cell Physiol. 2012;227:2722–2729. doi: 10.1002/jcp.23016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Winer JP, Janmey PA, McCormick ME, Funaki M. Bone marrow-derived human mesenchymal stem cells become quiescent on soft substrates but remain responsive to chemical or mechanical stimuli. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:147–154. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2007.0388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tsimbouri PM, Murawski K, Hamilton G, Herzyk P, Oreffo ROC, Gadegaard N, et al. A genomics approach in determining nanotopographical effects on MSC phenotype. Biomaterials. 2013;34:2177–2184. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Allen JL, Cooke ME, Alliston T. ECM stiffness primes the TGFβ pathway to promote chondrocyte differentiation. Mol Biol Cell. 2012;23:3731–3742. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-03-0172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tan S, Fang JY, Yang Z, Nimni ME, Han B. The synergetic effect of hydrogel stiffness and growth factor on osteogenic differentiation. Biomaterials. 2014;35:5294–5306. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chaudhuri O, Mooney DJ. Stem-cell differentiation: anchoring cell-fate cues. Nat Mater. 2012;11:568–569. doi: 10.1038/nmat3366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Murphy CM, Matsiko A, Haugh MG, Gleeson JP, O’Brien FJ. Mesenchymal stem cell fate is regulated by the composition and mechanical properties of collagen–glycosaminoglycan scaffolds. J Mech Behav Biomed. 2012;11:53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Trappmann B, Gautrot JE, Connelly JT, Strange DGT, Li Y, Oyen ML, et al. Extracellular-matrix tethering regulates stem-cell fate. Nat Mater. 2012;11:642–649. doi: 10.1038/nmat3339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yannas IV, Lee E, Orgill DP, Skrabut EM, Murphy GF. Synthesis and characterization of a model extracellular matrix that induces partial regeneration of adult mammalian skin. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 1989;86:933–937. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.3.933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harley BA, Spilker MH, Wu JW, Asano K, Hsu HP, Spector M, et al. Optimal degradation rate for collagen chambers used for regeneration of peripheral nerves over long gaps. Cells Tissues Organs. 2004;176:153–165. doi: 10.1159/000075035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spilker MH, Yannas IV, Kostyk SK, Norregaard TV, Hsu HP, Spector M. The effects of tubulation on healing and scar formation after transection of the adult rat spinal cord. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2001;18:23–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Caliari SR, Weisgerber DW, Ramirez MA, Kelkhoff DO, Harley BAC. The influence of collagen–glycosaminoglycan scaffold relative density and microstructural anisotropy on tenocyte bioactivity and transcriptomic stability. J Mech Behav Biomed. 2012;11:27–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lyons FG, Gleeson JP, Partap S, Coghlan K, O'Brien FJ. Novel microhydroxyapatite particles in a collagen scaffold: a bioactive bone void filler? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:1318–1328. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3438-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vickers SM, Gotterbarm T, Spector M. Cross-linking affects cellular condensation and chondrogenesis in type II collagen-GAG scaffolds seeded with bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. J Orthop Res. 2010;28:1184–1192. doi: 10.1002/jor.21113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Harley B, Leung J, Silva E, Gibson L. Mechanical characterization of collagen–glycosaminoglycan scaffolds. Acta Biomater. 2007;3:463–474. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Caliari SR, Gonnerman EA, Grier WK, Weisgerber DW, Banks JM, Alsop AJ, et al. Collagen scaffold arrays for combinatorial screening of biophysical and biochemical regulators of cell behavior. Adv Healthc Mater. 2014 doi: 10.1002/adhm.201400252. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/adhm.201400252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Martin TA, Caliari SR, Williford PD, Harley BA, Bailey RC. The generation of biomolecular patterns in highly porous collagen-GAG scaffolds using direct photolithography. Biomaterials. 2011;32:3949–3957. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Caliari SR, Mozdzen LC, Armitage O, Oyen ML, Harley BAC. Award winner in the young investigator category, 2014 society for biomaterials annual meeting and exposition, Denver, Colorado, April 16–19, 2014: periodically perforated core–shell collagen biomaterials balance cell infiltration, bioactivity, and mechanical properties. J Biomed Res A. 2014;102:917–927. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.35058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Caliari SR, Ramirez MA, Harley BAC. The development of collagen-GAG scaffold-membrane composites for tendon tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2011;32:8990–8998. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.08.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Turgeon AJ, Harley BA, Bailey RC. Chapter 15-Benzophenone-based photochemical micropatterning of biomolecules to create model substrates and instructive biomaterials. In: Matthieu P, Manuel T, editors. Methods cell biol. Academic Press; 2014. pp. 231–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sinsheimer JE, Jagodić V, Polak LJ, Hong DD, Burckhalter JH. Polycyclic aromatic isothiocyanate compounds as fluorescent labeling reagents. J Pharm Sci. 1975;64:925–930. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600640605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Martin TA, Herman CT, Limpoco FT, Michael MC, Potts GK, Bailey RC. Quantitative photochemical immobilization of biomolecules on planar and corrugated substrates: a versatile strategy for creating functional biointerfaces. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2011;3:3762–3771. doi: 10.1021/am2009597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Monaco E, Lima A, Bionaz M, Maki A, Wilson S, Hurley WL, et al. Morphological and transcriptomic comparison of adipose and bone marrow derived porcine stem cells. Open Tissue Eng Regen Med J. 2009:20–33. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Martin RM, Leonhardt H, Cardoso MC. DNA labeling in living cells. Cytom Part A. 2005;67A:45–52. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tierney CM, Jaasma MJ, O'Brien FJ. Osteoblast activity on collagen-GAG scaffolds is affected by collagen and GAG concentrations. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2009;91A:92–101. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Duffy GP, McFadden TM, Byrne EM, Gill SL, Farrell E, O'Brien FJ. Towards in vitro vascularisation of collagen-GAG scaffolds. Eur Cell Mater. 2011;21:15–30. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v021a02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yoshikawa Y, Abrahamsson SO. Dose-related cellular effects of platelet-derived growth factor-BB differ in various types of rabbit tendons in vitro. Acta Orthop. 2001;72:287–292. doi: 10.1080/00016470152846646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shah V, Bendele A, Dines JS, Kestler HK, Hollinger JO, Chahine NO, et al. Dose–response effect of an intra-tendon application of recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor-BB (rhPDGF-BB) in a rat achilles tendinopathy model. J Orthop Res. 2013;31:413–420. doi: 10.1002/jor.22222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Åhlén K, Ring P, Tomasini-Johansson B, Holmqvist K, Magnusson K-E, Rubin K. Platelet-derived growth factor-BB modulates membrane mobility of β1 integrins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;314:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.12.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bhakta G, Lim ZXH, Rai B, Lin T, Hui JH, Prestwich GD, et al. The influence of collagen and hyaluronan matrices on the delivery and bioactivity of bone morphogenetic protein-2 and ectopic bone formation. Acta Biomater. 2013;9:9098–9106. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liu H-W, Chen C-H, Tsai C-L, Hsiue G-H. Targeted delivery system for juxtacrine signaling growth factor based on rhBMP-2-mediated carrier-protein conjugation. Bone. 2006;39:825–836. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Thorpe SD, Buckley CT, Vinardell T, O'Brien FJ, Campbell VA, Kelly DJ. The response of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells to dynamic compression following TGF-β3 induced chondrogenic differentiation. Ann Biomed Eng. 2010;38:2896–2909. doi: 10.1007/s10439-010-0059-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mann BK, Schmedlen RH, West JL. Tethered-TGF-beta increases extracellular matrix production of vascular smooth muscle cells. Biomaterials. 2001;22:439–444. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(00)00196-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kovacevic D, Fox AJ, Bedi A, Ying L, Deng X-H, Warren RF, et al. Calcium-phosphate matrix with or without TGF-β3 improves tendon-bone healing after rotator cuff repair. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39:811–819. doi: 10.1177/0363546511399378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Toh CR, Fraterman TA, Walker DA, Bailey RC. Direct biophotolithographic method for generating substrates with multiple overlapping biomolecular patterns and gradients. Langmuir. 2009;25:8894–8898. doi: 10.1021/la9019537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Herman CT, Potts GK, Michael MC, Tolan NV, Bailey RC. Probing dynamic cell-substrate interactions using photochemically generated surface-immobilized gradients: application to selectin-mediated leukocyte rolling. Integr Biol. 2011;3:779–791. doi: 10.1039/c0ib00151a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Banks JM, Herman CT, Bailey RC. Bromelain decreases Neutrophil interactions with p-selectin, but not e-selectin, in vitro by proteolytic cleavage of pselectin glycoprotein Ligand-1. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e78988. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vickers SM, Squitieri LS, Spector M. Effects of cross-linking type II collagen-GAG scaffolds on chondrogenesis in vitro: dynamic pore reduction promotes cartilage formation. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:1345–1355. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Caliari SR, Harley BAC. Structural and biochemical modification of a collagen scaffold to selectively enhance MSC tenogenic, chondrogenic, and osteogenic differentiation. Adv Healthc Mater. 2014;3:1086–1096. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201300646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Paszek MJ, Zahir N, Johnson KR, Lakins JN, Rozenberg GI, Gefen A, et al. Tensional homeostasis and the malignant phenotype. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:241–254. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pountos I, Georgouli T, Henshaw K, Bird H, Jones E, Giannoudis PV. The effect of bone morphogenetic protein-2, bone morphogenetic protein-7, parathyroid hormone, and platelet-derived growth factor on the proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells derived from osteoporotic bone. J Orthop Trauma. 2010;24:552–556. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e3181efa8fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.McBeath R, Pirone DM, Nelson CM, Bhadriraju K, Chen CS. Cell shape, cytoskeletal tension, and RhoA regulate stem cell lineage commitment. Dev Cell. 2004;6:483–495. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00075-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]