Significance

This paper presents a new long speleothem δ18O time series from Xiaobailong cave in southwest China that characterizes changes in a major branch of Indian summer monsoon precipitation over the last 252 kyrs. This record shows not only 23-kyr precessional cycles punctuated by prominent millennial-scale weak monsoon events synchronous with Heinrich events in the North Atlantic, but also clear glacial–interglacial variations that are consistent with marine records but different from the cave records in East China. The speleothem records of Xiaobailong and other caves in East China show that the relationship between the Indian and the East Asian summer monsoon precipitation is not invariant, but rather varies on different timescales depending on the nature and magnitude of the climate forcing.

Keywords: Indian summer monsoon, stalagmite, δ18O, precipitation, glacial–interglacial

Abstract

A speleothem δ18O record from Xiaobailong cave in southwest China characterizes changes in summer monsoon precipitation in Northeastern India, the Himalayan foothills, Bangladesh, and northern Indochina over the last 252 kyr. This record is dominated by 23-kyr precessional cycles punctuated by prominent millennial-scale oscillations that are synchronous with Heinrich events in the North Atlantic. It also shows clear glacial–interglacial variations that are consistent with marine and other terrestrial proxies but are different from the cave records in East China. Corroborated by isotope-enabled global circulation modeling, we hypothesize that this disparity reflects differing changes in atmospheric circulation and moisture trajectories associated with climate forcing as well as with associated topographic changes during glacial periods, in particular redistribution of air mass above the growing ice sheets and the exposure of the “land bridge” in the Maritime continents in the western equatorial Pacific.

The Indian summer monsoon (ISM), a key component of tropical climate, provides vital precipitation to southern Asia. The ISM is characterized by two regions of precipitation maxima: a narrow coastal region along the Western Ghats, denoted by ISMA, with moisture from the Arabian Sea, and a broad “Monsoon Zone” around 20°N in northeastern India, denoted by ISMB, where storms emanate from the Bay of Bengal and whose rainfall variability is well correlated with that of “All India” rainfall (1). Multiple proxies obtained from Arabian Sea sediments have revealed the variability of summer monsoon winds on timescales of 101 to 105 y (e.g., refs. 2–6). Our understanding of the paleo-precipitation variability of ISMB remains incomplete, owing to the scarcity of long and high-resolution records. Here we present a 252,000-y-long speleothem δ18O record from Xiaobailong cave, southwest China and characterize variability in the ISMB precipitation on multiple timescales.

Xiaobailong (XBL, “Little White Dragon”) cave is located in Yunnan Province, southwestern China, near the southeastern edge of the Tibetan Plateau (103°21′E, 24°12′N, ∼1,500 m above sea level; SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Local climate is characterized by warm/wet summers and cool/dry winters. The mean annual precipitation of ∼960 mm (1960–2000) falls mostly from June through September (∼80%) (SI Appendix, Fig. S2), indicating the summer monsoon rainfall dominates the annual precipitation at the cave site. The temperature in the cave is 17.2 °C, close to local mean annual air temperature (17.3 °C).

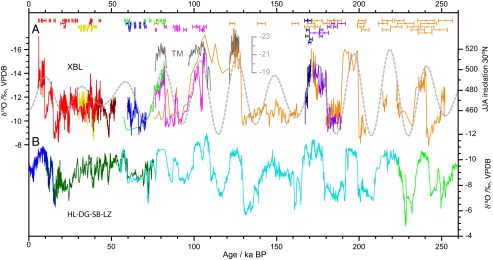

Eight stalagmites were collected from the inner chamber (∼350 m from the entrance) of the cave, where humidity is ∼100% and ventilation is confined to a small crawl-in channel to the outer chamber. One hundred four 230Th dates were determined on inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometers with typical relative error in age (2σ) of less than 1% (Methods and SI Appendix, Table S1 and Figs. S3 and S4). The ages vary monotonically with depth in the stalagmites (SI Appendix, Fig. S4) and the 230Th dates were linearly interpolated to establish chronologies. Measurements of calcite δ18O (δ18Oc) were made by isotope ratio mass spectrometer on a total of 1,896 samples from the eight stalagmites (Methods and SI Appendix, Table S2). By matching the chronology established by the absolute 230Th dates the δ18Oc time series of the different stalagmites were combined to form a single time series. The resulting XBL record (Fig. 1) covers the past 252,000 y, with an average resolution of 70 y between 5.0 and 80.0 thousand years before the present (ka BP, before 1950 AD) and 260 y between 80.0 and 252.0 ka BP, excluding several interruptions of calcite deposition (e.g., during the periods of 52.4–59.8, 164.0–167.2, 204.5–214.1, and 216.8–222.2 ka BP).

Fig. 1.

(A) The δ18Oc record of the stalagmites from Xiaobailong cave: XBL-3 (yellow), XBL-4 (green), XBL-7 (blue), XBL-26 (orange), XBL-27 (violet), XBL-29 (red), XBL-48 (pink), XBL-65 (dark blue), and XBL-1 (brown) (12). The gray curve shows a previously established δ18Oc record from the Tibetan Plateau (Tianmen Cave), indicating ISM variations during Marine Isotope Stage 5 (21). The 230Th dates and errors (2σ error bars) are color-coded by stalagmites. (B) The δ18Oc records of Hulu cave (dark green) (18), Dongge cave (blue) (19), Sanbao cave (sky blue) (20), and Linzhu cave (light green) (20). The δ18O scales for all records shown are reversed (increasing downward). Summer insolation at 30°N (gray dashed line) is integrated over June, July, and August (44).

In principle, variations in calcite δ18Oc of stalagmites could capture variations of δ18O in precipitation (δ18Op), cave temperature, which is close to the surface annual mean temperature, and kinetic loss of CO2 and evaporation of water during the calcite deposition. We rule out the kinetic fractionation processes, because δ18Oc records from different stalagmites in the XBL cave agree with one another within quoted dating errors over contemporaneous growth periods (Fig. 1), and δ13C records also replicate across speleothems within the cave, suggesting dominant climate control (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). Furthermore, the XBL δ18Oc records broadly resemble, on precessional and millennial timescales for overlapping periods (Fig. 1), speleothem records from Hulu, Dongge, Sanbao, and Linzhu caves (HL-DG-SB-LZ) in East China (7), providing another robust replication test and indicating that the δ18Oc signal in these stalagmites is primarily of climatic origin. The range of calcite δ18Oc change at XBL is ∼8.0‰ over 252 kyr. Because temperature-dependent fractionation between calcite and water is likely to be below 2‰ [estimated using ∼−0.23‰/°C (8), and assuming a maximum 8 °C difference between glacial and interglacial periods (9)], the shifts in stalagmite δ18Oc are primarily due to changes in meteoric precipitation δ18Op at the cave site.

We interpret XBL δ18Oc as an index of ISMB rainfall at a region denoted the Monsoon Zone-B, which encompasses the Monsoon Zone of northeastern India (1), the Himalayan foothills, Bangladesh, and northern Indochina. First, the Bay of Bengal supplies the bulk of moisture to both the Monsoon Zone-B and to XBL across the Indochinese Peninsula, and present-day summer precipitation in the two regions is positively correlated (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). Second, multiple climate model simulations show similar 850-hPa wind trajectories for these two regions for both present day and Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), suggesting moisture paths from the Bay of Bengal to XBL were relatively stable in the past (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). Third, the XBL δ18Oc record shows good agreement (r = 0.56), over the past 100 ka, with the salinity proxy, and by inference fluvial runoff proxy, reconstructed from ODP core 126 KL in the Bay of Bengal (10), with decreased δ18Oc values at XBL corresponding with lower salinity and hence increased precipitation, and vice versa (SI Appendix, Fig. S8). We hereafter define a “strong” ISMB as an increase of precipitation over the Monsoon Zone-B, and a corresponding decrease of δ18Oc value at XBL (SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods).

Variability of Indian Summer Monsoon

The dominant variability of XBL δ18Oc aligns well with Northern Hemisphere summer (June–August) insolation (NHSI) variation on a ∼23-kyr cycle associated with precession of the Earth’s orbit. Low δ18Oc values, heavier precipitation, or stronger ISMB are associated with higher NHSI, and vice versa. The record is also punctuated by many millennial-scale abrupt events (Fig. 1 and SI Appendix, Fig. S8). During the last glacial period (from ∼75 to ∼20 ka BP), when the XBL δ18Oc record has a mean resolution as high as ∼70 y, these abrupt events (∼15.9, ∼24.3, ∼30.1, ∼39.3, ∼48.2, and ∼62.0 ka BP) are marked by consistent increases of δ18Oc, or weaker ISMB, that are aligned with Heinrich events (11), thus suggesting a link between ISM and climate change in the North Atlantic (4, 12). However, decrease of δ18Oc during apparent warm Dansgaard/Oeschger periods is indistinguishable, likely owing to the resolution of the record.

On glacial–interglacial (∼100 kyr) timescales, the XBL calcite δ18Oc values vary between ∼−9‰ and ∼−11‰ during glacial periods (e.g., 20–75 ka BP) and are much higher than the ∼−14‰ of the interglacial optimum periods (e.g., high insolation periods within 75–130 ka BP) (Fig. 1), indicating relatively weak ISM during glacial periods. This is in agreement with other paleomonsoon records (2, 13), especially Chinese loess records that feature a significant glacial–interglacial cycle from 600 ka BP to the present (14).

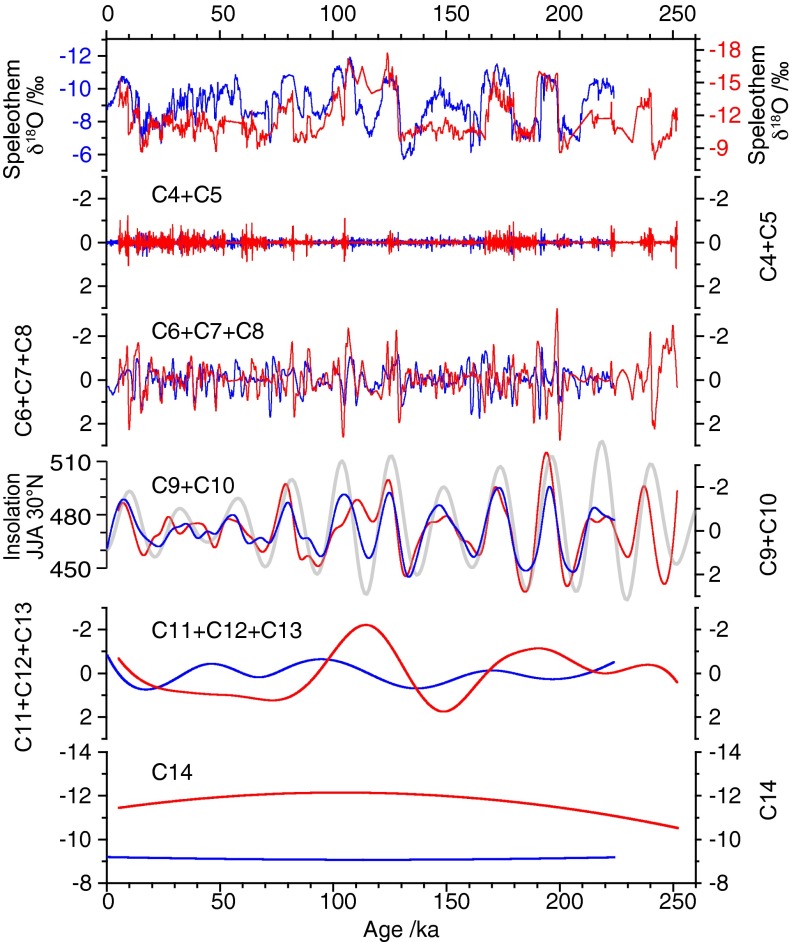

To separate XBL δ18Oc into its modes of variability, we applied ensemble empirical mode decomposition (EEMD), a new noise-assisted method (15) for analyzing nonlinear, nonstationary time series. Unlike Fourier or wavelet analysis, which decomposes a stationary time series into a chosen set of known functions and seeks each of their global (over the entire time series) amplitudes, EEMD determines, without prior assumptions, instantaneous frequencies and instantaneous amplitudes via a sifting algorithm (15–17). The resulting components are ordered by timescale, from the shortest to the longest (SI Appendix, Fig. S9). For the XBL record, the dominant variability (47.3% of the total variance) is captured by the component C9-10, and shows variability with a δ18Oc range of ∼5‰ that is coincident with NHSI at the precessional timescale (∼23 kyr) (Fig. 2). The next component (C11-13) captures 33% of the variance, with a δ18Oc range of ∼4‰. It peaks around 120 ka and has a broad minimum during the ice ages. Millennial scale variability (C6-8) has a δ18Oc range of ∼4 ‰ and captures 19% of the variance.

Fig. 2.

EEMD components of the XBL (red) and Hulu-Dongge-Sanbao (blue) composite time series over the last 252 kyr. During decomposition, noise of 0.4 (0.2 SD of the data) is added for the ensemble calculation, and the ensemble number is 300. Five EEMD components (i.e., sum of components 4–5, sum of components 6–8, sum of components 9–10, sum of components 11–13, and component 14) are presented. Component 14 indicates the overall trend. The individual components are shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S9.

A similar EEMD analysis was applied to the HL-DG-SB-LZ calcite δ18Oc time series from eastern China (7, 18–20) (Fig. 2). The dominant modes of variability at the East China caves are on precessional (69% of variance, δ18Oc range ∼6 ‰) and millennial (19% of the variance, δ18Oc range ∼4‰) timescales. Although these modes are similar to those at XBL, on glacial–interglacial timescales the HL-DG-SB-LZ δ18Oc range is only ∼1‰ compared with ∼4‰ at XBL and captures only 11% of the variance.

The correlation coefficient (r) between XBL and HL-DG-SB-LZ EEMD components is 0.8 on precessional timescale. The synchrony between the ISMB and East Asian Summer Monsoon (EASM), as revealed by EEMD analysis of the long XBL and HL-DG-SB-LZ δ18Oc time series (Figs. 1 and 2), confirms previous observations in intermittent speleothem records from South Asia and East Asia (21–25), thus strengthening the hypothesis that both the Indian and East Asian summer monsoons vary directly in response to changes in NHSI on precessional timescales (7, 26). Our results contradict the hypothesis that winter precipitation affects the phase of EASM cave δ18Oc signals (27) on precessional timescale, because changes in δ18Oc are synchronous between East China sites and XBL, where the contribution of winter precipitation is negligible. Instead, we point out that the phase of speleothem δ18Oc relative to the insolation signal could vary by up to several thousand years, depending on the choice of reference month(s).

There is no significant correlation (r = 0.2) between XBL and HL-DG-SB-LZ δ18Oc on a millennial timescale, even though both show increased δ18Oc values that are synchronous with Heinrich events within quoted errors. Changes in the North Atlantic Ocean during Heinrich events led to circulation changes over the entire Northern Hemisphere (28), and moisture from the Indian Ocean is hypothesized to dominate the isotope composition of precipitation in East Asia (e.g., refs. 28–30). However, two features may preclude attaining a significant correlation on millennial timescales between the two records: First, dating uncertainty in each record may affect the alignment between the two records, especially during the penultimate glacial–interglacial period, and second, several gaps in the XBL record are filled by linear interpolation and do not contain information on millennial timescales. If we correlate the two records at millennial timescales only for the period from 5.4 to 52.4 ka BP where both records are complete and the errors are relatively small, the correlation increases to r = 0.46, which is significant at the 0.01 level.

Different Responses of South and East Asian Speleothem δ18O on Glacial–Interglacial Timescales

Significant differences exist between the XBL and HL-DG-SB-LZ δ18Oc records. For example, the glacial–interglacial ranges, for example between marine isotope stages (MISs) 5 and 3, in δ18Oc are large and distinct at XBL and barely discernible in the HL-DG-SB-LZ record (Figs. 1 and 2). Furthermore, between MIS 5a and 5c, XBL shows an increasing trend, opposite to that in HL-DG-SB-LZ. The EEMD analysis also shows no significant relationship between XBL and East China speleothem δ18Oc records on the ∼100-kyr glacial–interglacial timescale: the correlation coefficient between the two EEMD components is only ∼0.1.

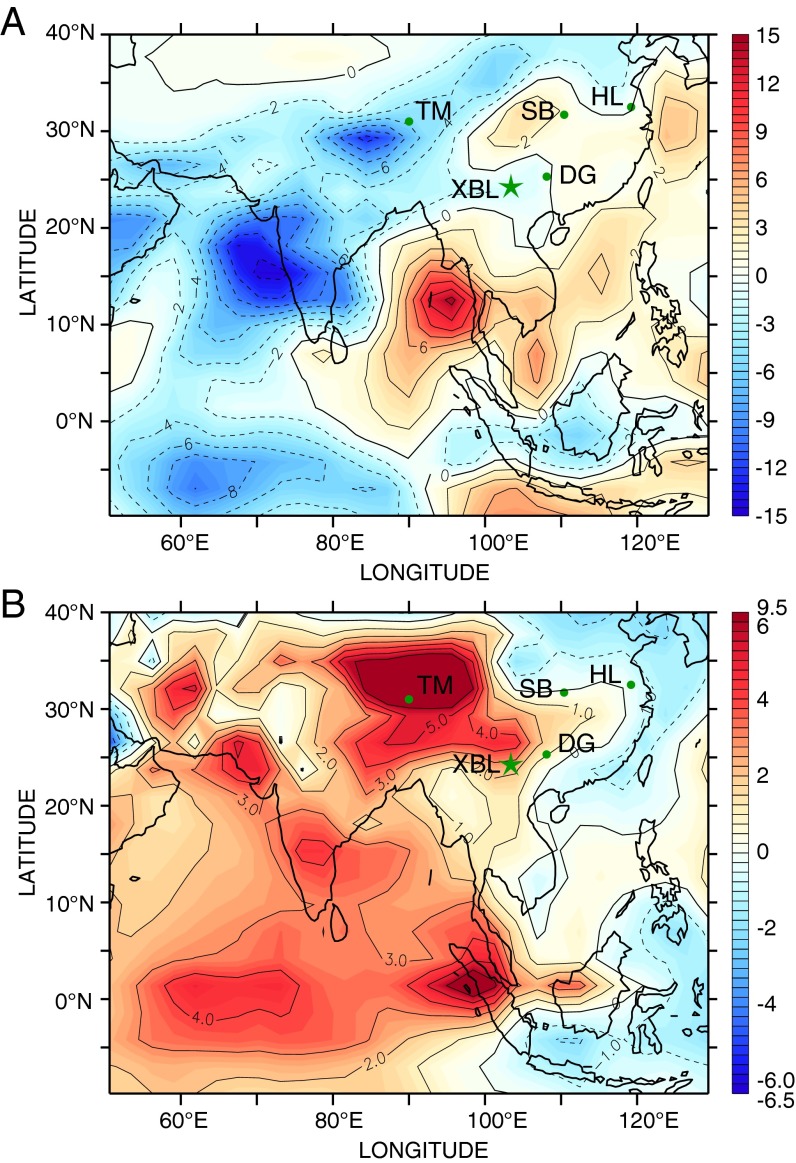

To understand the glacial–interglacial differences, we analyze the output of two runs of an isotope-enabled general circulation model with prescribed boundary conditions both for present day and for the LGM (SI Appendix, SI Materials and Methods and ref. 31). In the model, δ18O of ocean water was specified to be 0.5‰ for the present day and 1.7‰ during the LGM because of the loss of water depleted in heavy isotopes to the ice sheets. Relative to present day, LGM summer precipitation decreased substantially over the Indian Ocean and Indian subcontinent, but stratiform precipitation increased over the exposed continental shelf of East Asia (Fig. 3A). Similarly, LGM precipitation δ18Op was higher, by 2.0∼4.0‰, throughout the Indian Ocean and South Asia (including the XBL cave site) but showed either minor increases or decreases of 1.0–2.0‰ in East Asia (east of 105°E) (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Modeled difference (LGM minus present day) in June–August precipitation (mm/day, A) and amount-weighted precipitation δ18Op (‰, B). Markers indicate the locations of the following caves: Xiaobailong (XBL), Hulu (HL), Dongge (DG), Sanbao (SB), and Tianmen (TM).

To estimate the calcite δ18Oc from the modeled temperature and precipitation δ18Op, we first used a temperature fractionation of calcite δ18Oc of ∼−0.23‰/°C and modeled LGM temperature decreases at the cave sites (i.e., ∼4 °C at XBL and ∼6 °C at HL-DG-SB-LZ) (SI Appendix, Fig. S10), yielding a temperature-based ∼1.0‰ and ∼1.5‰ increase in δ18Oc during the LGM at XBL and at HL-DG-SB-LZ, respectively. The combined temperature and precipitation effect would yield a LGM calcite δ18Oc increase of ∼3.0–5.0‰ (∼2.0–4.0 + 1.0‰) at XBL and little change (∼0.5 to −0.5‰, or −1.0 to −2.0‰ + 1.5‰) at HL-DG-SB-LZ caves. The model results are thus consistent with the observations in speleothem records.

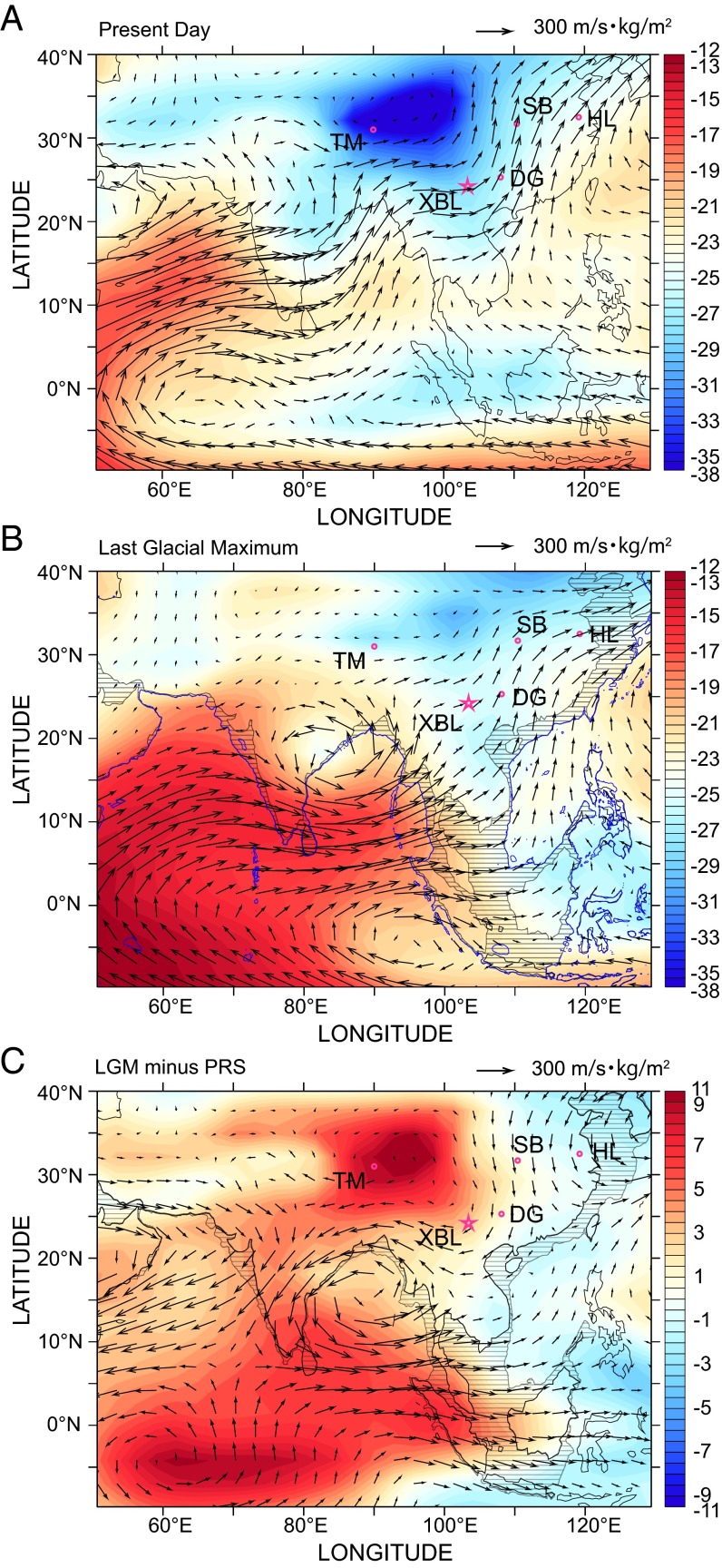

Our model, like other models in the Paleoclimate Modeling Intercomparison Project Phase II suite (9), shows a major trajectory of moisture advection from the northern reaches of the Bay of Bengal across the Yunnan Plateau and northern Indochina to XBL for the present day and the LGM (Fig. 4). Owing to the lower temperatures during the LGM, there was less moisture transport and precipitation along this path (Figs. 3A and 4). Together with the more enriched source water, LGM vapor δ18O (δ18Ov) was less depleted (Fig. 4 B and C) and δ18Op was more enriched (+2.0∼4.0‰) at XBL.

Fig. 4.

Modeled June–August vapor transport (arrows, m s−1 kg m−2) and isotopic composition of column integrated vapor (color-shading, ‰) during the present day (A) and the LGM (B) and the difference between LGM and present day (C). Dark gray lines indicate the present coastline; the blue lines and hatched area in B indicate the coastline and the exposed continental shelf, respectively during the LGM when sea level was ∼120 m lower than present day. Markers indicate the locations of the following caves: Xiaobailong (XBL), Hulu (HL), Dongge (DG), Sanbao (SB), and Tianmen (TM).

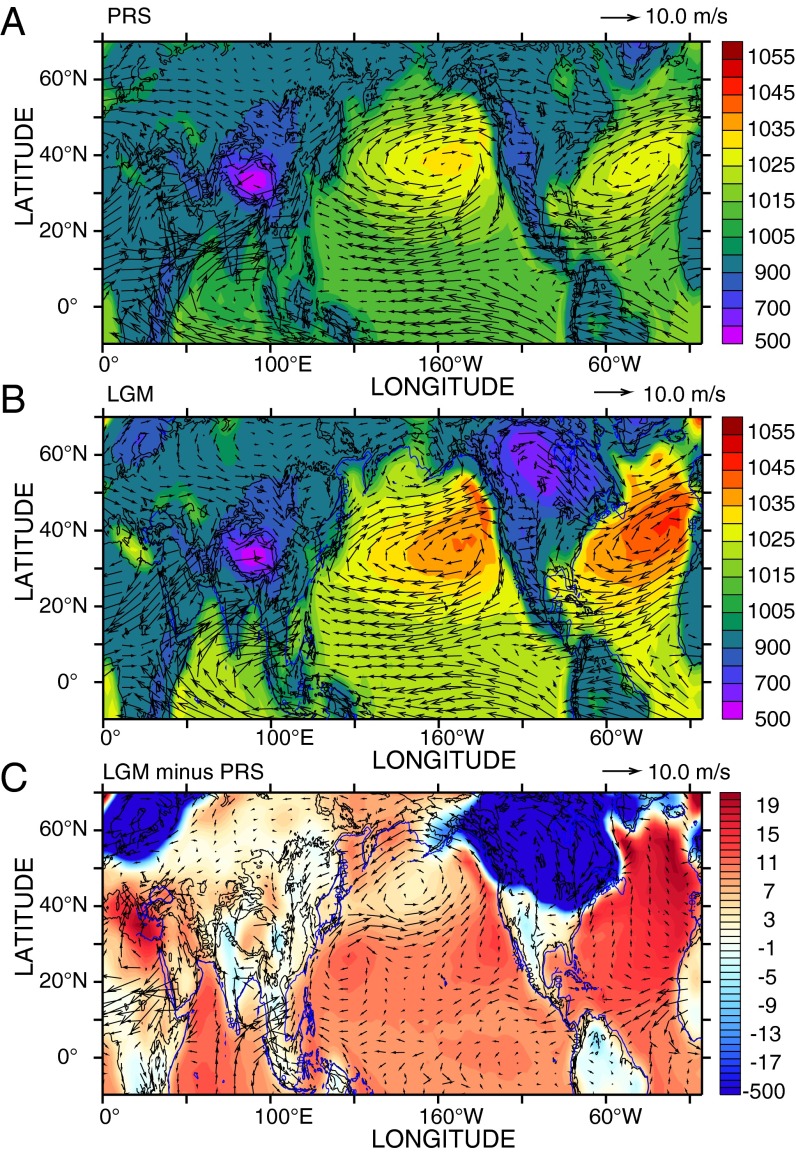

In contrast, the paths for moisture advection to East China are more varied, with three major paths to the region, a pattern consistent with modern observations*: from the Arabian Sea across the southern Bay of Bengal (the Indian Ocean path), from the South China Sea and tropical Pacific, and from the North Pacific (Figs. 4 and 5). Atmospheric circulation was different during the LGM, not only because of lower abundance of greenhouse gases, lower sea surface temperatures, and expanded sea ice coverage, but also because of altered topography with elevated continental glaciers and lowered sea level exposing new land surfaces. Off the Pacific coast of Asia, sea level during the LGM was ∼120 m lower than today (32), exposing the “land bridge,” the continental shelf around the Gulf of Thailand, South China Sea, and East China Sea, whereas there were only minor changes around the Bay of Bengal.

Fig. 5.

Modeled June–August surface pressure for (A) the present day and (B) the LGM and (C) the departure of LGM surface pressure from the present day (color, hectopascals). The arrows denote the corresponding near-surface winds (averaged over the lowest four layers, ∼300 hPa thick, of the model atmosphere). Topography (meters) is contoured. The thick blue line denotes the LGM coastline with a 120-m drop in sea level.

During the LGM, the Indian Ocean path of moisture advection to East China was shifted slightly equatorward and strengthened over the southern Bay of Bengal. This path contributed ∼30% and 15% of the LGM precipitation at Dongge and Hulu, respectively (28). The trajectory passed over the land bridge, where evaporation was reduced and stratiform precipitation increased relative to the present day (Fig. 3A), contributing to depleted δ18Ov of the vapor (Fig. 4 B and C) and lowered δ18Op values downstream at Dongge, Hulu, and other East China cave sites.

Moisture advection to the Hulu cave region in East China was more complicated during the LGM. Moisture advection from the South China Sea and the tropical Pacific was significantly increased compared with the present day, despite the ∼40% decrease in atmospheric water vapor in the LGM atmosphere (7%/K for 6-K decrease) (SI Appendix, Fig. S11). This is because southerly and southeasterly winds increased in response to a strengthened east–west pressure gradient between the continent and the Pacific Ocean as well as due to the enhancement of the subtropical high pressure system in the Pacific Ocean (Fig. 5), resulting from the redistribution of air mass from the continents to the oceans as glaciers grew. This increase in moisture flux was countered by an anomalous northeasterly flow from the North Pacific, as a result of greater surface pressure increase over the Bering Sea (∼10 hPa) than over the midlatitude ocean (∼5 hPa) (Fig. 5). This pattern of pressure difference induced anomalous southeasterly and northeasterly flows toward Eastern China and together these increased the moisture from the Pacific by ∼10% (SI Appendix, Fig. S11). As a result of the circulation changes, moisture convergence over the region of the East China caves (110–120E, 20–35N) increased and precipitation increases followed (SI Appendix, Fig. S11). In East China, the decrease in δ18Ov from increased precipitation competed with the increase in δ18O of the ocean source, resulting in little change in δ18Op at HL-DG-SB-LZ.

Taken all together, the circulation changes together with more enriched ocean water result in an unchanged and/or slightly depleted δ18Op over East China during the LGM, consistent with the observations at cave sites in East China during glacial periods.

Concluding Remarks

The XBL δ18Oc record documents the variability of the ISMB precipitation on glacial–interglacial, precessional, and millennial timescales over the last 252,000 y. Unlike speleothem records from East China, XBL is concordant with records of the ISMB from marine sediments and loess records on a glacial–interglacial timescale.

Our modeling results show that glacial–interglacial changes in atmospheric circulation and rainfall are manifested in isotopically different ways at XBL and in East China, with more depleted precipitation δ18Op during interglacial than during glacial periods at XBL versus nearly unchanged precipitation δ18Op in East China. We further suggest that reduced evaporation over exposed continental shelf during the LGM could have contributed to the depleted precipitation δ18Op downstream at some of the cave sites in East China.

Our study, along with other paleoclimate modeling studies, puts forth pieces of the puzzle of how regional circulation and hydrology respond to different climate forcings or perturbations. The model results taken all together show that variations in δ18Op and, by inference, δ18Oc of speleothems, reflect regional and hemispheric scale variations in vapor flux as well as in situ condensation and evaporation in the atmospheric column (33–36).

The Indian Ocean moisture path to East Asia seems robust, even though the magnitudes of the fluxes vary, in the comparison of the present day and the LGM here and in a comparison of the LGM with or without the Heinrich perturbation (28). In this study, changes in the tropical and North Pacific moisture fluxes dominated the δ18Op changes in East China during the LGM. Our result that the land bridge exposed during the LGM led to enhanced summer large-scale stratiform precipitation is not inconsistent with the reduction in annual mean convection over the Sunda Shelf (e.g., ref. 34). Although the complexity of circulation changes in influencing precipitation changes of a site or a region is not a surprise, the long speleothem records, such as the XBL δ18Oc data presented here, present unique opportunities for improving climate models and for testing hypotheses about past hydroclimate changes.

Methods

U-Series Dating and Stable Isotope Analysis.

All stalagmites were cut into halves along the growth axis and their surfaces were polished. SI Appendix, Fig. S3 illustrates images of the stalagmites and the 230Th dating positions. Subsamples were drilled along growth axes for 230Th dating at the Minnesota Isotope Laboratory on the inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometers (Thermo-Finnigan ELEMENT and Thermo Fisher NEPTUNE, refs. 37 and 38, respectively). The chemical procedures used to separate the uranium and thorium for 230Th dating are similar to those described in ref. 39.

Subsamples for stable isotope analysis were collected in two ways: (i) drilling with a dental drill bit 0.5 mm in diameter directly from the polished half of the stalagmite at an average interval of 2, 1, or 0.5 mm along stalagmite axes, depending on sample growth rates, and (ii) cutting the stalagmite into a 1- × 0.5-cm slab using a diamond saw and then scraping off perpendicularly to the growth axes of the stalagmites at a mean resolution of ∼20 subsamples per millimeter. The second method was applied for sections between 0 and 95 mm from the top of stalagmite XBL-29. We performed the stable isotopic analysis on all subsamples collected through the first method and every 10th sample from the second method. A total of 1,896 oxygen isotopic values were obtained on a Finnigan MAT-252 mass spectrometer equipped with Kiel Carbonate Device III at the Institute of Earth Environment, Chinese Academy of Sciences. International standard NBS19 and interlaboratory standard TTB1 were run for every 10–15 samples and arbitrarily selected duplicate measurements were conducted every 10–20 samples, respectively, to check for homogeneity and reproducibility. All oxygen isotopic values are reported in δ notation, the per mil deviation relative to the Vienna Pee Dee Belemnite (VPDB) standard (δ18O = [((18O/16O)sample/(18O/16O)standard − 1) × 1000]). Standard results show that the precision of δ18Oc analysis is better than 0.15‰ (2σ).

Isotope-Enabled General Circulation Model Simulations.

The climate model used in this project incorporated HDO and H218O into the NCAR CAM2. We then ran this isotope-enabled model with fixed sea surface temperature (SST) and sea ice distributions for the present day and the LGM (40). SST in the present-day run is given by the climatological monthly mean derived from observations from 1949 to 2001. In the LGM run, we used monthly SST and sea ice distribution simulated by the fully coupled atmosphere-land-ocean-ice Community Climate System Model (41) with atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), and nitrous oxide (N2O) at 185 ppmv, 350 ppbv, and 200 ppbv, respectively. The LGM ICE-5G reconstruction is used for the continental ice sheet extent and topography prescription. Surface ocean δ18O values for the present day and LGM are prescribed as 0.5‰ (42) and 1.7‰ (43), respectively. The isotope-CAM LGM simulation is initialized using the atmospheric state from the equilibrium simulation of the CCSM LGM run and is integrated forward for 20 y using SSTs and glacial and sea ice extents from CCSM as boundary conditions. The present-day simulation was integrated for 15 y. In both cases, averages of the last 10 y were used for the analysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. P. Molnar and the reviewers for valuable suggestions. This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China grants; National Basic Research Program of China; the Knowledge Innovation Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences; National Science Foundation Grants EAR-0909195 and EAR-1211925 (to I.Y.F.) and EAR-0908792 and EAR-1211299 (to R.L.E.and H.C.); Taiwan Ministry of Science and Technology Grant MOST-103-2119-M-002-022 (to C.-C.S.); and a Singapore National Research Foundation fellowship.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*Liu TW, Tang W, Second International Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission Science Conference, September 6–10, 2004, Tokyo.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1424035112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Gadgil S. The Indian monsoon and its variability. Annu Rev Earth Planet Sci. 2003;31:429–467. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prell WL, Kutzbach JE. Monsoon variability over the past 150,000 years. J Geophys Res. 1987;92:8411–8425. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sirocko F, et al. Century-scale events in monsoonal climate over the past 24,000 years. Nature. 1993;364:322–324. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schulz H, Rad UV, Erienkeuser H. Correlation between Arabian Sea and Greenland climate oscillations of the past 110,000 years. Nature. 1998;393:54–57. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clemens SC, Prell WL. A 350, 000 year summer-monsoon multi-proxy stack from the Owen Ridge, Northern Arabian Sea. Mar Geol. 2003;201:35–51. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupta AK, Anderson DM, Overpeck JT. Abrupt changes in the Asian southwest monsoon during the Holocene and their links to the North Atlantic Ocean. Nature. 2003;421(6921):354–357. doi: 10.1038/nature01340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Y, et al. Millennial- and orbital-scale changes in the East Asian monsoon over the past 224,000 years. Nature. 2008;451(7182):1090–1093. doi: 10.1038/nature06692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim ST, O’Neil JR. Equilibrium and nonequilibrium oxygen isotope effects in synthetic carbonates. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1997;61:3461–3475. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braconnot P, et al. Results of PMIP2 coupled simulations of the Mid-Holocene and Last Glacial Maximum – Part 1: Experiments and large-scale features. Clim Past. 2007;3:261–277. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kudrass HR, Hofmann A, Doose H, Emeis K, Erlenkeuser H. Modulation and amplification of climatic changes in the Northern Hemisphere by the Indian summer monsoon during the past 80 k.y. Geology. 2001;29:63–66. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heinrich H. Origin and consequences of cyclic ice rafting in the Northeast Atlantic Ocean during the past 130,000 years. Quat Res. 1988;29:142–152. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cai YJ, et al. High-resolution absolute-dated Indian Monsoon record between 53 and 36 ka from Xiaobailong Cave, southwestern China. Geology. 2006;34:621–624. [Google Scholar]

- 13.An Z, et al. Glacial-interglacial Indian summer monsoon dynamics. Science. 2011;333(6043):719–723. doi: 10.1126/science.1203752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu H, Zhang F, Liu X, Duce RA. Periodicities of palaeoclimatic variations recorded by loess-paleosol sequences in China. Quat Sci Rev. 2004;23:1891–1900. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu Z, Huang NE. Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition: A noise-assisted data analysis method. Adv Adapt Data Anal. 2009;1:1–41. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu Z, Huang NE, Long SR, Peng C-K. On the trend, detrending, and variability of nonlinear and nonstationary time series. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(38):14889–14894. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701020104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu Z, Huang NE, Wallace JM, Smoliak BV, Chen X. On the time-varying trend in global-mean surface temperature. Clim Dyn. 2011;37:759–773. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang YJ, et al. A high-resolution absolute-dated late Pleistocene Monsoon record from Hulu Cave, China. Science. 2001;294(5550):2345–2348. doi: 10.1126/science.1064618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dykoski CA, et al. A high-resolution, absolute-dated Holocene and deglacial Asian monsoon record from Dongge Cave, China. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2005;233:71–86. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng H, et al. Ice age terminations. Science. 2009;326(5950):248–252. doi: 10.1126/science.1177840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cai YJ, et al. Large variations of oxygen isotopes in precipitation over south-central Tibet during Marine Isotope Stage 5. Geology. 2010;38:243–246. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fleitmann D, et al. Holocene ITCZ and Indian monsoon dynamics recorded in stalagmites from Oman and Yemen (Socotra) Quat Sci Rev. 2007;26:170–188. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sinha A, et al. Variability of Southwest Indian summer monsoon precipitation during the Bølling-Ållerød. Geology. 2005;33:813–816. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cai YJ, et al. The Holocene Indian monsoon variability over the southern Tibetan Plateau and its teleconnections. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2012;335/336:135–144. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheng H, Sinha A, Wang X, Cruz F, Edwards R. The Global Paleomonsoon as seen through speleothem records from Asia and the Americas. Clim Dyn. 2012;39:1045–1062. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kutzbach JE. Monsoon climate of the Early Holocene: Climate experiment with the Earth’s orbital parameters for 9000 years ago. Science. 1981;214(4516):59–61. doi: 10.1126/science.214.4516.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clemens SC, Prell WL, Sun Y. Orbital-scale timing and mechanisms driving Late Pleistocene Indo-Asian summer monsoons: Reinterpreting cave speleothem δ18O. Paleoceanography. 2010;25(4):PA4207. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pausata FSR, Battisti DS, Nisancioglu KH, Bitz CM. Chinese stalagmite δ18O controlled by changes in the Indian monsoon during a simulated Heinrich event. Nat Geosci. 2011;4:474–480. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maher BA. Holocene variability of the East Asian summer monsoon from Chinese cave records: A re-assessment. Holocene. 2008;18:861–866. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dayem KE, Molnar P, Battisti DS, Roe GH. Lessons learned from oxygen isotopes in modern precipitation applied to interpretation of speleothem records of paleoclimate from eastern Asia. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2010;295:219–230. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee JE, Fung I, DePaolo DJ, Henning CC. Analysis of the global distribution of water isotopes using the NCAR atmospheric general circulation model. J Geophys Res. 2007;112:D16306. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peltier WR. Global glacial isostasy and the surface of the ice-age Earth: The ICE-5G (VM2) model and GRACE. Annu Rev Earth Planet Sci. 2004;32:111–149. [Google Scholar]

- 33.LeGrande AN, Schmidt GA. Sources of Holocene variability of oxygen isotopes in paleoclimate archives. Clim Past. 2009;5:441–455. [Google Scholar]

- 34.DiNezio PN, et al. The response of the Walker circulation to Last Glacial Maximum forcing: Implications for detection in proxies. Paleooceanogrpahy. 2011;26(3):PA3217. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee JE, et al. Asian monsoon hydrometeorology from TES and SCIMACHY water vapor isotope measurement and LMDZ simulations: Implications for speleothem climate record interpretation. J Geophys Res. 2012;117:D15112. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Battisti DS, Ding Q, Roe GH. Coherent pan-Asian climate and isotopic response to orbital forcing of tropical insolation. J Geophys Res Atmos. 2014;119:11997–12020. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shen C-C, et al. Uranium and thorium isotopic and concentration measurements by magnetic sector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Chem Geol. 2002;185:165–178. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cheng H, et al. Improvements in 230Th dating, 230Th and 234U half-life values, and U–Th isotopic measurements by multi-collector inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2013;371:82–91. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Edwards RL, Chen JH, Wasserburg GJ. 238U-234U-230Th-232Th systematic and the precise measurement of time over the past 500,000 years. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 1987;81:175–192. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee JE, Fung I, DePaolo DJ, Otto-Bliesner B. Water isotopes during the Last Glacial Maximum: New general circulation model calculations. J Geophys Res. 2008;113:D19109. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Otto-Bliesner BL, et al. Last Glacial Maximum and Holocene climate in CCSM3. J Clim. 2006;19:2526–2544. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hoffmann G, Werner M, Heimann M. Water isotope module of the ECHAM atmospheric general circulation model: A study on timescales from days to several years. J Geophys Res. 1998;103:16871–16896. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schrag DP, Hampt G, Murray DW. Pore fluid constraints on the temperature and oxygen isotopic composition of the glacial ocean. Science. 1996;272(5270):1930–1932. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5270.1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Berger A, Loutre MF. Insolation values for the climate of the last 10 million years. Quat Sci Rev. 1991;10:297–317. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.