Abstract

Background

This study describes time-trends on epidemiology, subtypes and histopathological entities of osteosarcoma (OS) in a nationwide and unselected cohort of OS patients in Norway between 1975 and 2009. Few nationwide studies are published, and we still have particularly limited knowledge regarding patients not included in clinical trials comprising about half of the OS population.

Method

Histologically verified skeletal OS for all subgroups were included, resulting in 473 eligible cases from a total of 702 evaluated patients. To ensure completeness, the present cohort was based on all cases reported to the Norwegian Cancer Registry, complemented with data from all Norwegian hospitals involved in sarcoma management. Survival analyses were performed with overall and sarcoma-specific survival as endpoints.

Results

Mean annual age-standard incidence amounted to about 3.8 per million in male and 2.8 per million in female with no clear time-trends. The male to female ratio was 1.4. Peak incidence was observed in the second decade for both genders. Conventional OS comprised 71.2% of all cases, while low grade OS represented 10.4% and telangiectatic OS only 1.3%. The most common primary site of OS was femur and tibia, respectively. The axial to appendicular ratio increased with the age. The overall 10-year survival did increase from about 30% during the late 1970s to around 50% 20 years later, with no subsequent improvement during the last two decades. Axial tumours, age above 40 years and overt metastatic disease at time of diagnosis were all negative prognostic factors.

Conclusion

No improvement in the overall survival for OS since the 1990s was documented. The survival rates are still poor for elderly people, patients with axial disease and in the primary metastatic setting. The average incidence rate of skeletal OS in Norway was in line with international figures.

Despite osteosarcoma (OS) being the most common primary malignant bone tumour [1], it is a rare disorder that displays considerable heterogeneity and appears as clinical entities showing a great span in tumour biology and prognosis [2]. The incidence of OS is bimodally distributed by age with a dominant peak in adolescence and a smaller, less well-studied one among the elderly [3]. The incidence rate among children and adolescents appears to be relatively consistent throughout the world but varies more at older age [3].

Most commonly, OS affects the metaphyseal part of long bones [2,4] as classical OS [5]; i.e. extremity localised primary tumour, high grade histology, no detectable metastasis at primary diagnosis and age below 40 years. Most of OS clinical trials involve just this cohort [5]. The implementation of adjuvant chemotherapy in the late 1970s made important progress in the treatment of high grade OS [6,7]. However, the prognosis is still grave for other subgroups of OS [5,7]. Many of these patients do not receive adequate surgery because of a challenging or inaccessible primary tumour sites or do not tolerate aggressive chemotherapy due to high age.

To our knowledge, very few nationwide, population-based studies have been published on clinical presentation and prognosis of OS [8–13]. Most studies are solely based on Cancer Registries, institutional series or experiences from cooperative sarcoma societies [14,15]. Here we present all cases of skeletal OS in Norway from 1975 until 2009 by use of multiple sources. The selected time period coincides with the introduction of effective modern multi-modal assessment and treatment. Starting year of 1975 was chosen to increase the number of patients and capture the era well before the prospective clinical OS studies began in Scandinavia [7]. The last available inclusion year was 2009.

The main purpose of this study was to calculate time-trends on incidence rates and survival outcomes. We have also studied the distribution of all anatomical subgroups and histological sub-entities of skeletal OS, including primary site of the disease and the percentage of primary metastatic disease.

Material and methods

Patient data

The reporting of malignant neoplasms to the Norwegian Cancer Registry (NCR) has been compulsory since 1953 and the completeness has been reported to be higher than 95% [16]. Due to the reporting rules, with a unique individual 11-digit identification number to every Norwegian resident by the Statistics Norway since 1960, most cases are prospectively reported from different sources to the NCR. The database is continuously updated and matched to information from the Cause of Death Registry (CDR), and the National Registry on vital status and migration.

Data on bone cancers were extracted from the NCR using the International Classification of Disease for Oncology second edition (ICD-0-2). The main codes for OS are M918 and M919. We have also extracted data from spindle cell non-osteosarcomas arising from bone tissue (SCS) in the gross material, code M881, M883 and M889, and data from more unspecific bone tumours, code M880 and M882 in order to capture OS cases wrongly classified among these ICD-codes. Further, International Classification of Disease (ICD8) was used for cases diagnosed from 1975 to 1978, International Classification of Disease (ICD9) from 1979 to 1994, and International Classification of Disease (ICD10) from 1995 and onwards. The inclusion criteria for this study required Norwegian residence and Norwegian personal identification number.

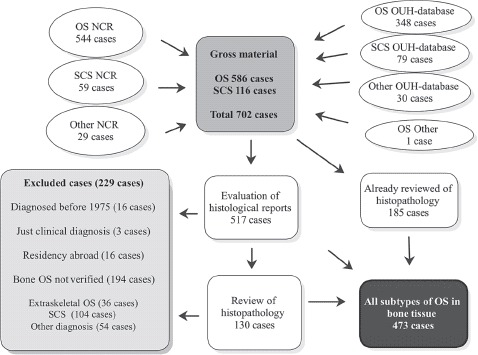

A total of 544 people were reported as OS including all subgroups to the NCR from 1975 until 2009 and 59 people as SCS (Figure 1). Furthermore, 29 people were reported as more unspecific bone tumours. This cohort was complemented with data from all hospitals involved in sarcoma management in Norway, mainly Norwegian Radium Hospital (NRH). The latter hospital, now part of Oslo University Hospital (OUH), has since 1980 prospectively registered all new sarcoma cases in its unique database comprising a total of 348 cases of OS by the end of 2009 and 79 SCS for the same period. The gross study material amounted to 702 cases (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing the inclusion of skeletal osteosarcoma (OS) in the study, 1975–2009. NCR, The Norwegian Cancer Registry; OUH, Oslo University Hospital; SCS, spindle cell non-osteosarcoma arising in bone.

Histopathology

Except for two cases with an obvious clinical and pathological OS diagnosis confirmed by fine-needle aspiration cytology [17], only histologically verified OS in bone tissue were included in this study. All cases were supplemented with clinical records. All tumours for all subgroups were graded histologically according to a four-grade malignancy scale [18] and classified according to current WHO criteria [4], with minor modifications. The aim was that all cases should have been examined by at least two senior sarcoma pathologists at a University Hospital, preferably by OUH, Haukeland University Hospital or by an internationally distinguished colleague. The first author (KB) identified all earlier patients having undergone such a re-evaluation from the OUH. In total 185 cases were either verified as OS in the OUH sarcoma database, as part of the inclusion in one of The Scandinavian Sarcoma Group (SSG) protocols for osteosarcoma, or as part of other research projects at the OUH. Third and last author (AB, ØB) re-evaluated all histological reports of the remaining 517 cases (702–185 cases). We have not retrospectively reviewed radiographic images.

In total 229 cases were rejected and 130 were retrieved from the files and re-examined by at least one of four senior pathologists due to somewhat questionable pathology reports. Among these, most low grade or extraskeletal OS were re-considered if they had not already got a final diagnosis by second opinion at the Mayo Clinic. In total the net population amounted to 473 cases (Figure 1).

Third and last author (AB, ØB) determined the dominating morphological phenotype for all subtypes of OS based on the histological reports. Exceptions were the cases of parosteal, periosteal and small cell OS. The reports from primary biopsy were compared with successive surgical specimens. A mixed phenotype was introduced when there was no obviously dominating phenotype.

Quality control

Multiple and partially overlapping data and registry sources supplemented with clinical data regarding treatment and follow-up, survival and cause of death ensured completeness and good quality. The current database included information relevant for this study: gender, age at diagnosis of OS, anatomic localisation of primary tumour, histological subtype of OS including phenotypical differentiation, grade of histology, metastases at the time of diagnosis, pathological fracture, previous cancer treatment, predisposition for OS, status follow-up, date of death and cause of death.

Time of diagnosis was the starting point in calculation of overall survival and sarcoma-specific survival (SSS). Date and cause of death was primarily retrieved from CDR. A total of 234 people died due to OS, i.e. 82.4% of all deaths in the cohort per November 2013. However, when other clinically available information was scrutinised, we found that additional 22 patients died due to OS. Hence, 256 people died from OS, i.e. 90.1% of all deaths, and this number was used in the calculations regarding SSS.

The closing date for the cohort was set to November 2013 regarding date of death. The endpoint for survivors was July 2013 due to a common registration delay at the CDR. The mean/median follow-up time for survivors was 18/17 years. All clinical follow-up data were updated as close to the closing date as possible. One emigrated patient was censored at date of last follow-up.

Time of diagnosis was based on data from the NCR, which is dependent on several aspects, first of all time of biopsy. However, we have controlled these figures against corresponding results from the OUH database. Here the date of diagnosis to a larger degree equals time of biopsy report. We accepted up to 60 days of difference between these two sources. All larger deviations were further re-examined in addition to all cases with a verified metastatic disease few weeks after primary diagnosis. We defined metastasis within six weeks from primary diagnosis as overt metastasis at time of diagnosis. Thus, time of diagnosis may influence on the question regarding primary metastatic disease within this context.

Statistical methods

The database was made by using Microsoft Office Excel 2010 and later Microsoft Office Access 2003. The statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 21 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and Stata version 13.1 (Stata corporation, College Station, TX, USA). Survival analyses were performed using the Kaplan-Meier method with overall survival and SSS as endpoints. The log-rank test was used to compare survival curves. The incidence calculations were based on the WHO-age standard incidence rate per million per year, and the results are presented as three-year moving average.

Ethical approval

The database is located at the NCR. Only relevant data that is regulated by the NCR legislation were included. The Regional Ethical Committee was informed, although the study did not require a formal ethical approval. The Cancer Registry Data Delivery Unit approved the use of these data for international publishing. However, the interpretation and reporting of these data are the sole responsibility of the authors, and no endorsement by the NCR is intended nor should be inferred.

Results

Clinicopathological data

We attempted to secure a complete population-based, nationwide and unselected cohort of bone OS patients. The net population amounted to 473 cases, from a gross study material of 702 cases (Figure 1). In total 586 OS patients were identified, all subgroups included. Hence, our approach, using different data sources, increased the gross number of OS patients by 42 cases (7.2%) compared to the 544 cases reported to the NCR (586–544 cases). Of these patients, 28 were nevertheless reported to the NCR, but by use of wrong ICD-0-2 codes. The remaining 14 cases had residency abroad and were correctly excluded from the NCR. All excluded cases due to wrong diagnosis are presented in Table I.

Table I.

Cases not verified as bone osteosarcoma.

| Cases | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Spindle cell non-osteosarcoma arising from bone tissue | 104 | 53.6 |

| Spindle cell non-osteosarcoma arising from soft tissue | 7 | 3.6 |

| Spindle cell non-osteosarcoma, uncertain origin | 1 | 0.5 |

| Extraskeletal osteosarcoma | 36 | 18.6 |

| Chondrosarcoma | 12 | 6.2 |

| Chondrosarcoma with a component of osteosarcoma | 1 | 0.5 |

| Chondroblastoma | 1 | 0.5 |

| Carcinosarcoma | 4 | 2.1 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 3 | 1.5 |

| Ewing sarcoma | 3 | 1.5 |

| Giant-cell tumour of bone | 2 | 1.0 |

| Chordoma | 1 | 0.5 |

| Liposarcoma | 1 | 0.5 |

| Mesothelioma | 1 | 0.5 |

| Mesenchymal tumour | 1 | 0.5 |

| Neuroblastoma | 1 | 0.5 |

| Osteoblastoma | 1 | 0.5 |

| Unclassified sarcoma | 3 | 1.5 |

| Uncertain diagnosis, but not osteosarcoma | 8 | 4.1 |

| Not representative biopsy | 3 | 1.5 |

| Total | 194 | 100 |

Incidence

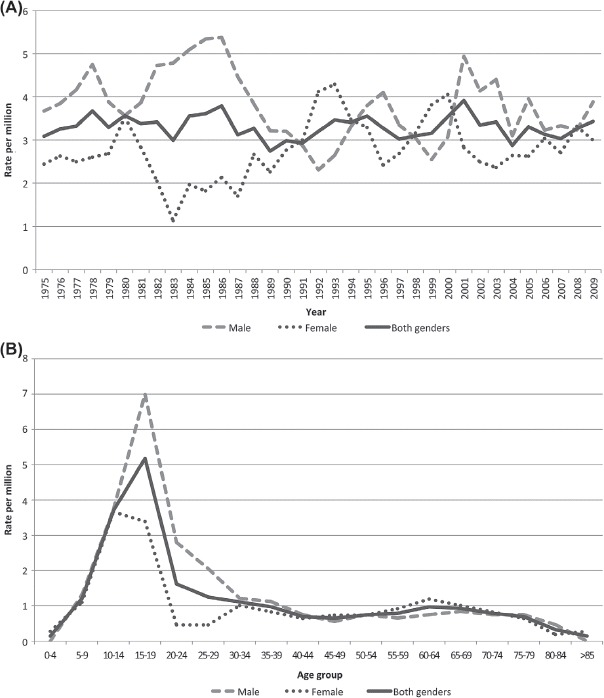

The average incidence rate for skeletal OS in both genders was slightly above 3.3 per million for the period 1975–2009. The male to female ratio was 1.4 for all patients; 1.7 for age under 40 years and 0.9 for elderly patients. Age standardised rates fluctuated within a range of about two to five per million over the period in males, and about one to four in females with no clear time-trends (Figure 2A). The incidence peaked in males at age 15–19 and in females at age 10–14 (Figure 2B). The frequency of OS patients was independent of geographic residence in Norway.

Figure 2.

Three-year moving average of age-standardised incidence rates of osteosarcoma (males, females and both genders) in Norway, 1975–2009 (A). Age-specific incidence rates of osteosarcoma (males, females and both genders), 1975–2009 (B).

Histopathology

All verified cases of OS in bone are presented in Table II. We did not identify any high grade surface OS, which is a rare entity [4]. Ten cases of low grade OS of maxilla and mandible were classified among the OS of the jaw since they did not fit the entity low grade central OS. Of these, one had osteoblastic differentiation, five chondroblastic, one fibroblastic and three with a mixed phenotype, respectively. In addition we registered 19 cases as low grade central OS, even though seven of these were located in flat or small bones (clavicle, metacarp, costa, scapula, columna vertebralis and pelvis). The low grade central OS were subtyped as osteoblastic (12), chondroblastic (1), fibroblastic (4), mixed (1) and not otherwise specified (1). Six OS underwent subsequent transformation from low to high grade OS during follow-up, of these three low grade central, one low grade of the jaw and two parosteal OS.

Table II.

Histological subtypes of the osteosarcomas (OS) included in the cohort, mainly based on the present WHO classification, 1975–2009.

| 1975–1979 | 1980–1989 | 1990–1999 | 2000–2009 | Total | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional OS | 51 | 108 | 78 | 100 | 337 | 71.2 |

| Osteoblastic | 22 | 54 | 36 | 46 | 158 | |

| Chondroblastic | 7 | 15 | 9 | 11 | 42 | |

| Fibroblastic | 7 | 5 | 6 | 17 | 35 | |

| Mixed | 15 | 30 | 23 | 25 | 93 | |

| NOSa | 4 | 4 | 1 | 9 | ||

| OS of the jaw | 2 | 5 | 15 | 9 | 31 | 6.6 |

| Osteoblastic | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 6 | |

| Chondroblastic | 1 | 2 | 3 | 6 | ||

| Fibroblastic | 2 | 1 | 3 | |||

| Mixed | 1 | 3 | 1 | 5 | ||

| NOSa | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Low grade histology | 2 | 6 | 2 | 10 | ||

| Telangiectatic OS | 3 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 1.3 | |

| Parosteal OS | 2 | 5 | 9 | 4 | 20 | 4.2 |

| High grade | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | ||

| Low grade | 1 | 5 | 8 | 2 | 16 | |

| Periosteal OS | 2 | 2 | 0.4 | |||

| Small cell OS | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0.6 | ||

| Low grade central OS | 2 | 4 | 8 | 5 | 19 | 4.0 |

| OS with OPFb, high grade | 6 | 10 | 13 | 22 | 51 | 10.8 |

| Osteoblastic | 3 | 6 | 4 | 13 | 26 | |

| Chondroblastic | 3 | 3 | 6 | |||

| Fibroblastic | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Mixed | 2 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 11 | |

| Telangiectatic | 1 | 1 | ||||

| NOSa | 1 | 3 | 4 | |||

| OS with OPFb, low grade | 4 | 4 | 0.8 | |||

| Total | 67 | 136 | 125 | 145 | 473 | 100 |

anot otherwise specified; bosteosarcoma predisposing factor.

Among the group of osteosarcoma predisposing factor (OPF) we included radiation-induced OS and patients with predisposition for OS, i.e. retinoblastoma, Paget's disease, Li-Fraumeni syndrome, fibrous dysplasia and lastly a more unclassified group. The high grade OS cases with OPF comprised 33 cases of radiation-induced OS, four cases of Paget's disease, two cases of verified Li-Fraumeni disease, three case arising from previous fibrous dysplasia and four cases of retinoblastoma. Among the latter, two cases were in combination with previous radiotherapy. In seven cases, we just had an indication of a hereditary predisposition for OS, but not a genetically confirmed syndrome. The low grade OS cases with OPF included one osteoblastic, two chondroblastic and one fibroblastic subtype.

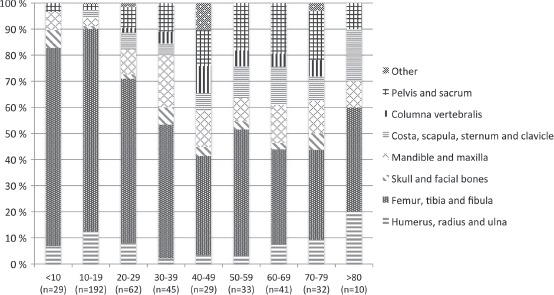

Anatomic localisation

The distribution of OS according to primary anatomical site of disease is shown in Table III. Distribution of age and primary site of OS at diagnosis is presented in Figure 3. We observed a substantial decrease in the percentage of extremity skeletal localisation among the elderly OS patients compared to teenagers and young adults. Univariate logistic regression with axial versus extremity localisation as dependent variable and age as continuous covariate gave a significant result (p < 0.001).

Table III.

Distribution of osteosarcoma according to primary site of disease, 1975–2009.

| Cases | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Humerus | 36 | 7.6 |

| Radius, ulna | 6 | 1.3 |

| Femur | 186 | 39.3 |

| Tibia | 84 | 17.8 |

| Fibula | 20 | 4.2 |

| Skull and facial bones | 13 | 2.7 |

| Mandible and maxilla | 41 | 8.7 |

| Costa | 20 | 4.2 |

| Scapula, sternum, clavicle | 9 | 1.9 |

| Columna vertebralis | 12 | 2.5 |

| Pelvis, sacrum | 40 | 8.5 |

| Other | 6 | 1.3 |

| Total | 473 | 100 |

Figure 3.

Distribution of age and primary site of osteosarcoma at diagnosis, 1975–2009.

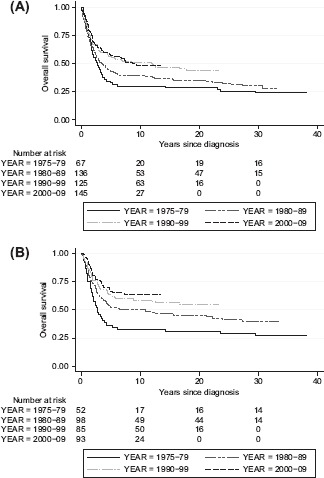

Survival analysis

We confirmed the well-known increase in long time survival since 1975 due to multidisciplinary team and multimodal treatment including chemotherapy (p = 0.017) shown in Figure 4A. Nevertheless, no improvement since the 1990s was found when we just compare the survival for the two last decades (p = 0.889). We observed an increased overall survival in patients younger than 40 years during the whole time period (p = 0.001), as illustrated in Figure 4B, in contrast to elderly patients (p = 0.08), data not shown. The overall survival after 10 years for those over 40 years was 22.4% and only 10.1% after 30 years. Correspondingly, the overall survival of the whole study population amounted to 44.0% after 10 years and 34.0% after more than 30 years. Presence of metastasis at the time of diagnosis clearly worsened the survival with a five-year overall survival of just 13.8%.

Figure 4.

Overall survival for the whole study population (A) and under 40 years at the time of diagnosis (B) dependent of time of diagnosis, 1975–2009.

Table IV shows the results of univariate analysis of five-year SSS by decades of diagnosis, gender, primary site, age, metastasis at time of diagnosis and subtypes of OS. Axial tumour, age above 40 years at the time of diagnosis and primary metastatic disease were all significant negative prognostic factors. Percentage of survival was also dependent of subtype of OS, e.g. 30.7% of patients with OPF were alive after five years, with even worse prognosis among 34 patients with radiation-induced OS (25.5%) including one case of low grade OS. The average age at diagnosis for the latter group was 54.5 years, with an axial to appendicular ratio of 4.7. In contrast, 91.7% of all patients with low grade OS were alive five years after time of diagnosis.

Table IV.

Five-year sarcoma-specific survival (SSS) for patients according to different characteristics of osteosarcoma (OS), 1975–2009.

| Number of patients | Five-year SSS in% |

95% CIa in % | pb |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time of diagnosis | 0.003 | |||

| 1975–1979 | 67 | 35.6% | 24.3–47.0% | |

| 1980–1989 | 136 | 45.0% | 36.4–53.2% | |

| 1990–1999 | 125 | 56.8% | 47.7–64.9% | |

| 2000–2009 | 145 | 58.7% | 50.2–66.2% | |

| Gender | 0.603 | |||

| Male | 273 | 49.6% | 43.4–55.5% | |

| Female | 200 | 52.8% | 45.7–59.4% | |

| Axial vs. extremity | < 0.001 | |||

| Axial | 135 | 39.8% | 31.4–48.1% | |

| Extremity | 338 | 55.4% | 49.9–60.5% | |

| Age at diagnosis | < 0.001 | |||

| < 40 years | 328 | 57.6% | 52.1–62.7% | |

| > 40 years | 145 | 36.0% | 28.2–43.8% | |

| Metastasis at diagnosis | < 0.001 | |||

| No | 379 | 60.6% | 55.5–65.3% | |

| Yes | 85 | 13.8% | 7.4–22.1% | |

| Type malignant bone lesion | < 0.001 | |||

| Conventional OS | 337 | 48.1% | 42.7–53.3% | |

| Low grade OS | 49 | 91.7% | 79.3–96.8% | |

| OS with OPFc, high grade | 51 | 30.7% | 18.7–43.6% |

aconfidence interval; blog-rank test; costeosarcoma predisposing factor.

Discussion

This study presents incidence rates and survival outcomes in a complete nationwide cohort of Norwegian bone OS patients by including all registered OS patients at NCR and OUH as well as OS treated at other Norwegian hospitals during modern chemotherapy era. All excluded cases are presented, and unlike most publications, all histological subgroups of skeletal OS are included. All except 130 cases were diagnosed by at least two senior sarcoma pathologists at a University Hospital at primary diagnosis and were not re-evaluated like in the Finnish studies [9,10]. The remaining 130 cases were histologically re-examined in connection to our study with two exceptions regarding fine-needle aspiration cytology.

The average incidence rates of OS in our cohort, about 3.8 per million in male and 2.8 per million in females, are in line with a previous large international study [3], though substantially higher than reported by Sampo et al. [9]. The dropout ratios in the Finnish studies [9,10] were significant higher than in our study (Table I), especially in their first publication [10]. This may partly explain their lower OS incidence.

We confirmed a decrease in the overall male to female ratio of OS among elderly compared with the younger age groups [3], in contrast to Whelan et al. [11]. We observed no significant change in the incidence across all groups since 1975, in line with the analysis of Whelan et al. [11]. The peak in adolescent patients occurred earlier in females than in males due to earlier puberty, as reported throughout the world [3].

Interestingly, we did not confirm the clear bimodal distribution found in previous studies [3,11]. This may be related to a very low incidence of Paget's disease among elderly in Norway compared to several other countries. Paget's disease is considered to represent about half of all cases of OS in patients aged 60 years or older [4]. According to Colina et al. there is a marked geographic variation observed in the prevalence of Paget's disease, with a particular high prevalence noted in the UK, Australia, New Zealand and USA [19]. Mirabello et al. also reported a comparatively lower second incidence peak among elderly in Europe, excluding UK [3].

OS is usually of high grade malignancy [1,2] and accounted for 89.6% of all OS in our cohort. The conventional type is the most common OS, and comprised 79.5% of all high grade OS and 71.2% of all OS in the cohort, somewhat lower than previously reported [20]. This difference may partly be explained by our minor modifications of the current WHO criteria [4] concerning OS of the jaw and OS cases with OPF. We observed about the same relative incidence of fibroblastic and chondroblastic phenotypes with the highest frequency being the osteoblastic variant (Table II), as previously reported [1,4].

In contrast, we found just 1.3% of the total cases to be of the telangiectatic type of OS, excluding one case with OPF, a clearly smaller proportion less than 4% previously reported [1,4]. Correspondingly, Sampo et al. presented nine cases of telangiectatic OS from 1970 to 2005, i.e. 2.9% of all confirmed OS [9,10]. The deviations from previous findings may be related to the fact that we only included “clean” telangiectatic OS in our cohort. We had at least 10 cases of “mixed” phenotype where telangiectatic OS poses one of several differentiation patterns, classified as conventional OS (Table II). Histological examination is subjective with poor intra- and inter- reproducibility [21]. This may also explain some of the differences. Two of seven telangiectatic OS in our cohort had pathological fracture at clinical presentation, as reported in the literature [4].

OS is the most common radiation-induced sarcoma [4], representing 7.2% of all OS in our cohort; somewhat larger than earlier publications [1,4]. The prognosis of these patients is poor compared to the other subgroups of OS. In that respect, both a high percentage of axial localisation and relatively high age at time of diagnosis seemingly worsened the outcome.

Low grade OS is divided into parosteal and low grade central OS according to WHO [4]. In total 10.4% of all cases in the current study were low grade OS, excluding four cases of high grade parosteal OS, about the same level as Sampo et al. [9]. As previously mentioned, low grade OS arising in the jaw and cases with OPF were grouped into separate entities. Still 19 cases were registered as low grade central OS, which is approximately three times higher than earlier reported [4].

The most common primary sites of OS are the long bones of the limbs, as observed in most former series [1,2,8,11]. The axial to appendicular ratio, independent of age, was 0.4 in this study in line with two previous publications from Norway and Finland [9,22], but higher than other findings [7,8,10,12]. We confirm a higher percentage of axial tumours in elderly people [7,11].

The multimodal treatment approach of OS from the late 1970s [6,7] explains the increased overall survival in our study (Figure 4A). The improvement mainly gained younger patients. We found no improvement in the overall survival since the 1990s among all age groups, which is in agreement with Whelan et al. [11] and Sampo et al. [9]. A recent review concluded that modern chemotherapy in conjunction with surgery has reached a plateau phase since the 1980s, with about 60–70% five-year event free survival in extremity localised non-metastatic disease, and with a poorer prognosis for other groups [7].

Patients with non-extremity OS have a worse outcome than primary disease located within the appendicular skeleton [7,11,22], as confirmed in our study (Table IV). We also confirmed the poor prognosis in patients over 40 years [5,7,8,11], often linked to a higher rate of axial tumour, more frequent metastases at presentation, and decreased tolerance of chemotherapy [7]. Grimer et al. have demonstrated that patients over 40 years old ideally should be treated similarly to those in the younger age group; aggressive chemotherapy and complete surgical resection whenever possible [23]. Hence, it is not age as such that affects the survival for elderly people [23].

Patients with metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis had a dismal outcome. Approximately 18% of all patients in our study had metastatic disease at the time of OS diagnosis, comparable to other studies [7,8,24]. We found neither clear time-trends from 1975 to 2009, nor any major differences dependent of axial versus appendicular skeleton. Five-year overall and SSS for primary metastatic OS was 13.8% in line with Curry et al. [8] and Mialou et al. [25]. However, direct comparison is difficult to evaluate due to multifactorial differences between these studies.

The strength of the present study, in our opinion, is the validated reliability of the database due to multiple and partially overlapping data and registry sources supplemented with clinical data from all Norwegian hospitals involved in sarcoma management. We have conducted a total re-evaluation of all histological reports for the whole cohort but only approximately 20% of all cases were formally re- examined histologically as part of this project. We cannot rule out that the quality could have been even better with a full uniform histological re-examination of all cases in the cohort. However, a consequential and significant disadvantage of such an approach is the potential lack of available histological specimens for re-examination. This might be an even larger problem in nationwide, population-based studies than studies based on, e.g. institutional series or experiences from cooperative sarcoma societies.

In conclusion, our incidence rate is in line with a large previous study [3], despite lack of a clear bimodal age distribution. We found no improvement in the overall survival since the 1990s. The survival rates are inferior in elderly people, patients with axial disease and patients with metastatic disease at diagnosis. Hence, novel strategies for treatment of OS are needed to further improve outcome.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge oncologists Kirsten Sundby Hall, Odd R. Monge, Heidi Knobel and Eivind Smeland for indispensable support regarding clinical records and also to pathologist Anna Elisabeth Stenwig, now retired. Technical support from Elbj⊘rg Johansen and Aage F. Johansen is also appreciated. The authors report no conflicts of interest. This project is supported by the South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority Research Program with a pilot project supported by the National Resource Centre for Sarcomas in Norway.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- [1].Unni KK, Inwards CY. Dahlinś bone tumors. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Huvos AG. Bone tumors. Diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Mirabello L, Troisi RJ, Savage SA. International osteosarcoma incidence patterns in children and adolescents, middle ages and elderly persons. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:229–34. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Fletcher CDM, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn PCW, Mertens F. WHO classification of tumours of soft tissue and bone. 4th ed. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Bruland OS, Pihl A. On the current management of osteosarcoma. A critical evaluation and a proposal for a modified treatment strategy. Eur J Cancer. 1997;33:1725–31. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(97)00252-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Rosen G, Marcove RC, Caparros B, Nirenberg A, Kosloff C, Huvos AG. Primary osteogenic sarcoma: The rationale for preoperative chemotherapy and delayed surgery. Cancer. 1979;43:2163–77. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197906)43:6<2163::aid-cncr2820430602>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Luetke A, Meyers PA, Lewis I, Juergens H. Osteosarcoma treatment – Where do we stand? A state of the art review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2014;40:523–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Curry H, Horne G, Devane P, Tobin H. Osteosarcoma in New Zealand: An outcome study comparing survival rates between 1981–1987 and 1994–1999. N Z Med J. 2006;119:U2234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Sampo M, Koivikko M, Taskinen M, Kallio P, Kivioja A, Tarkkanen M, et al. Incidence, epidemiology and treatment results of osteosarcoma in Finland – a nationwide population-based study. Acta Oncol. 2011;50:1206–14. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2011.615339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Sampo MM, Tarkkanen M, Kivioja AH, Taskinen MH, Sankila R, Bohling TO. Osteosarcoma in Finland from 1971 through 1990: A nationwide study of epidemiology and outcome. Acta Orthop. 2008;79:861–6. doi: 10.1080/17453670810016966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Whelan J, McTiernan A, Cooper N, Wong YK, Francis M, Vernon S, et al. Incidence and survival of malignant bone sarcomas in England 1979–2007. 2012;131:E508–17. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Harvei S, Solheim O. The prognosis in osteosarcoma: Norwegian National Data. Cancer. 1981;48:1719–23. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19811015)48:8<1719::aid-cncr2820480806>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Stiller CA, Passmore SJ, Kroll ME, Brownbill PA, Wallis JC, Craft AW. Patterns of care and survival for patients aged under 40 years with bone sarcoma in Britain, 1980–1994. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:22–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Ferrari S, Palmerini E, Staals EL, Mercuri M, Franco B, Picci P, et al. The treatment of nonmetastatic high grade osteosarcoma of the extremity: Review of the Italian Rizzoli experience. Impact on the future. Cancer Treat Res. 2009;152:275–87. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-0284-9_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Bielack S, Jurgens H, Jundt G, Kevric M, Kuhne T, Reichardt P, et al. Osteosarcoma: The COSS experience. Cancer Treat Res. 2009;152:289–308. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-0284-9_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Tingulstad S, Halvorsen T, Norstein J, Hagen B, Skjeldestad FE. Completeness and accuracy of registration of ovarian cancer in the cancer registry of Norway. 2002;98:907–11. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Sathiyamoorthy S, Ali SZ. Osteoblastic osteosarcoma: Cytomorphologic characteristics and differential diagnosis on fine-needle aspiration. Acta Cytol. 2012;56:481–6. doi: 10.1159/000339196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Bjerkehagen B, Wejde J, Hansson M, Domanski H, Bohling T. SSG pathology review experiences and histological grading of malignancy in sarcomas Acta Orthop. 2009;80:31–6. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Colina M, La Corte R, De Leonardis F, Trotta F. Paget's disease of bone: A review. Rheumatol Int. 2008;28:1069–75. doi: 10.1007/s00296-008-0640-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Bielack S, Carrle D, Casali PG. Osteosarcoma: ESMO clinical recommendations for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(Suppl 4):137–9. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Mangrud OM, Waalen R, Gudlaugsson E, Dalen I, Tasdemir I, Janssen EA, et al. Reproducibility and prognostic value of WHO1973 and WHO2004 grading systems in TaT1 urothelial carcinoma of the urinary bladder. PloS One. 2014;9:e83192. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Saeter G, Bruland OS, Folleras G, Boysen M, Hoie J. Extremity and non-extremity high-grade osteosarcoma – the Norwegian Radium Hospital experience during the modern chemotherapy era. Acta Oncol. 1996;35(Suppl 8):129–34. doi: 10.3109/02841869609098531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Grimer RJ, Cannon SR, Taminiau AM, Bielack S, Kempf-Bielack B, Windhager R, et al. Osteosarcoma over the age of forty. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:157–63. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(02)00478-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Bacci G, Ferrari S, Longhi A, Forni C, Zavatta M, Versari M, et al. High-grade osteosarcoma of the extremity: Differences between localized and metastatic tumors at presentation. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2002;24:27–30. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200201000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Mialou V, Philip T, Kalifa C, Perol D, Gentet JC, Marec-Berard P, et al. Metastatic osteosarcoma at diagnosis: Prognostic factors and long-term outcome – the French pediatric experience. Cancer. 2005;104:1100–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]