Abstract

Personalized medicine could revolutionize how primary care physicians treat chronic disease and how researchers study fundamental biological questions. To realize this goal we need to develop more robust, modular tools and imaging approaches for in vivo monitoring of analytes. In this report, we demonstrate that synthetic nanosensors can measure physiologic parameters with photoacoustic contrast, and we apply that platform to continuously track lithium levels in vivo. Photoacoustic imaging achieves imaging depths that are unattainable with fluorescence or multiphoton microscopy. We validated the photoacoustic results that illustrate the superior imaging depth and quality of photoacoustic imaging with optical measurements. This powerful combination of techniques will unlock the ability to measure analyte changes in deep tissue and will open up photoacoustic imaging as a diagnostic tool for continuous physiological tracking of a wide range of analytes.

Keywords: Diagnostic, continuous monitoring, bipolar, nanoparticle, nanomedicine

Medical imaging and diagnostics are two key pillars of personalized medicine and the study of disease. However, in order to advance these fields we need to develop novel approaches and technologies for in vivo imaging and monitoring of physiologically important analytes. Conventional optical imaging techniques suffer from the limited penetration depth of light and the loss of spatial resolution in deep tissue due to scattering. Photoacoustic imaging 1-3 mitigates many of these shortcomings and achieves imaging depths of up to several centimeters with acoustically defined spatial resolution. Many photoacoustic techniques focus on imaging either endogenous signals such as hemoglobin 4, or exogenous contrast agents such as carbon nanotubes 5, gold nanoparticles 6 and iron oxide nanoparticles 7. These measurements are particularly valuable for examining local oxygenation or tissue structure, but there is immense value in the untapped use of photoacoustics as a measurement tool to monitor changes in analyte concentrations deep within intact tissue. Some development work has focused on the combination of photoacoustics with molecular imaging probes for distribution 8, pH 9-10, oxygen/reactive oxygen species 11-12, or glucose 13, but these probes are available for limited targets and do not incorporate the ability to tune sensor response to desired physiological ranges.

Fluorescent nanosensors are well-established, and multiple distinct designs have proven capable of monitoring a wide range of analytes in vitro 14-15 and in vivo 16-19. These nanosensors offer several key advantages that make them suitable for continuously tracking analyte levels. A great deal of development work has established methods for both producing nanosensors and tuning a nanosensor’s analytical performance to physiological concentration ranges. These nanosensors are particularly appealing because they have the added benefit of a modular design. With the modular optode design, the nanosensor’s target analyte, spectral properties, and response range arise from straightforward design choices such as component ratios. However, the current design of these optode-based nanosensors cannot overcome the limitations of fluorescent imaging, particularly in deep tissues.

In this paper, we formulate, characterize, and validate lithium-sensitive nanosensors for photoacoustic measurements and compare to results obtained with fluorescence measurements. Lithium is a valuable model system for photoacoustic imaging because continuous measurement technologies such as photoacoustics can provide a method to track systemic concentrations of therapeutic drugs and improve disease management. Lithium is a common treatment for bipolar disorder, but it has both a narrow therapeutic window (0.6 – 1.2 mM) and a low toxic dose (~ 2 mM) 20-21, demonstrating a need for continuous monitoring.

Results

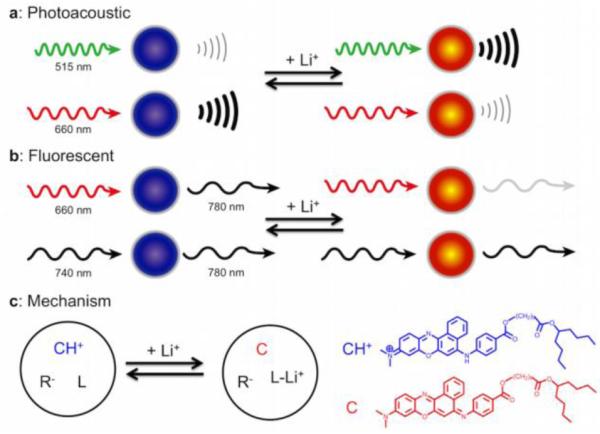

The core mechanism for lithium recognition and signaling in these nanosensors is based on the well-established optode approach, demonstrated previously for several ionic and small molecule analytes 14, 18, 22-23. In this instance, lithium is recognized by a lithium selective crown ether ionophore, Lithium Ionophore VI 24, and extracted from bulk solution into the hydrophobic polymer core of the nanosensor (Figure 1). This extraction of a cation into the core of the polymer causes a shift in the internal pH of the nanosensor, altering the protonation state of a chromoionophore, which alters the optical properties of the nanosensor. Both the absorption spectrum and fluorescence intensity of the nanoparticles change as a function of lithium concentration. These optical changes occur at visible wavelengths, which presents difficulties in obtaining good fluorescent signals for in vivo imaging, but represent an opportunity for photoacoustic imaging.

Figure 1.

Nanosensors for detecting lithium can be monitored with both photoacoustic (a) and fluorescent (b) imaging techniques. Both approaches use multiwavelength ratiometric imaging to generate a response that changes with lithium concentration and minimizes nonspecific changes. In photoacoustic monitoring, two wavelengths are used to interrogate the chromoionophore embedded in the sensors, and the photoacoustic waves from each wavelength change as lithium concentration changes. In fluorescent imaging, a near-IR fluorophore is added to the sensors. The intensity of FRET from the chromoionophore to the near IR dye changes with lithium concentration, whereas directly exciting the near-IR dye does not change intensity—serving as a sensing reference. The fundamental mechanism of the lithium response (c) is lithium extraction by an ionophore (L) into the core of the nanosensor, which deprotonates a chromoionophore (CH+), changing the optical properties of the nanosensor. An additive (R-) balances the charge inside the sensor.

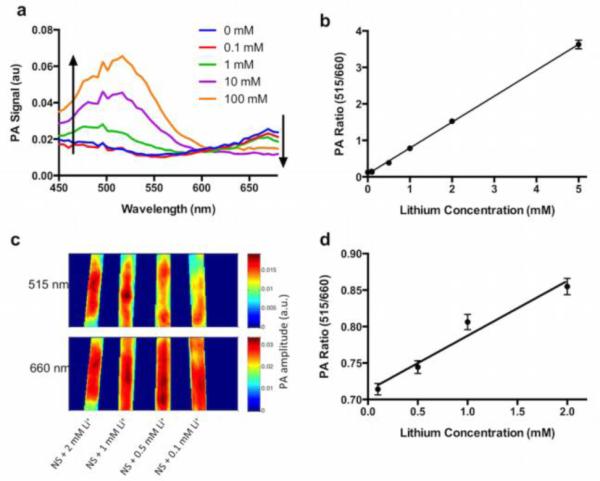

Photoacoustic imaging is based on the absorption of photons by a molecule and the conversion to ultrasonic waves via the photoacoustic effect 25. When the absorption spectrum of the chromoionophore changes, the photoacoustic spectrum changes accordingly (Figures 1a, 2a). As the lithium concentration increases, the absorbance and photoacoustic intensity at 515 nm increases, and the absorbance and photoacoustic intensity at 660 nm decreases. Importantly, these changes in photoacoustic intensity result from the nanosensor and chromoionophore, because the analyte itself does not possess any intrinsic photoacoustic properties. From the measurements at these two peak wavelengths (Figure 2b), we can form a ratiometric index that increases linearly with lithium concentration but is not susceptible to common artifacts such as variation in nanosensor concentration or number. Photoacoustics can also be used to image these nanosensors under ~1.5 mm of chicken muscle tissue (Figure 2c, 2d). The signal attenuation at 515 nm is larger than at 660 nm, which decreases the contrast at that wavelength and reduces the ratiometric values for the data while remaining linear over the physiologically relevant range of lithium.

Figure 2.

Responses of photoacoustic nanosensors to lithium within physiological ranges. The photoacoustic spectrum (a) has two peaks centered at 515 and 660 nm. The 515 peak increases with lithium concentrations, and the 660 peak decreases. In vitro measurement of this ratio (b) responds to lithium and is insensitive to common confounding factors such as concentration of nanosensors. Photoacoustic imaging of nanosensors under a 1.5 mm thick layer of chicken tissue (c) shows signal attenuation of the 515 nm peak, while retaining the ratiometric lithium response (d). PA: photoacoustics.

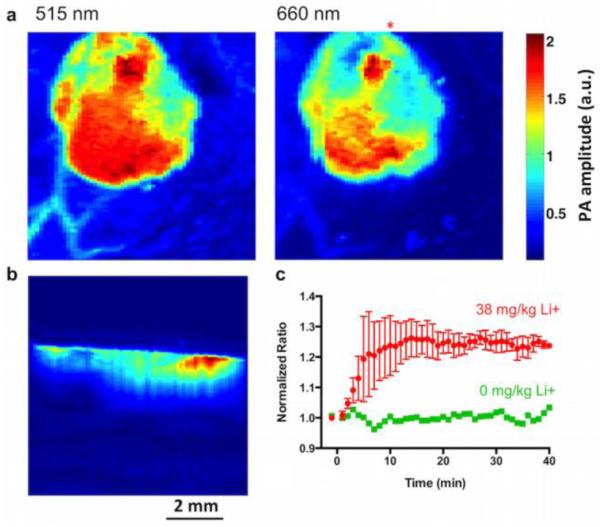

Lithium selective nanosensors injected into the skin of mice can be imaged with photoacoustic tomography (Figure 3a), but a key advantage of photoacoustics is the ability to collect data from the entire tissue volume (Figure 3b, Supporting Video 1). Importantly, the data collected in the surface projection is a result of the entire sensor injection, rather than the nanosensors closest to the skin surface, as is the case with fluorescence imaging. Upon i.p. administration of lithium to the animals at a physiological concentration of 38 mg/kg (~2.5 mM blood concentration)26, the nanosensor photoacoustic ratio increased by 25 percent. This clear response to the increasing lithium has a time to peak concentration of 14 minutes (Figure 3c, Supporting Fig. 17-18) compared with 2 hours for humans 27. It is already known that lithium elimination pharmacokinetics are an order of magnitude more rapid in mice 28; it is likely that the peak time is also faster due to these increased kinetics. Importantly, this data was acquired without blood sampling and from the entire depth of the nanosensors, which means the sensors are closer to the capillary bed which should minimize response lag time and more accurately reflect blood concentrations.

Figure 3.

Photoacoustic nanosensors imaged in a small animal model. Dual wavelength images of the nanosensor injection using photoacoustic tomography (a) clearly show the boundary of the injection. A depth profile (b) taken along the line below the red asterisk in (a) shows the nanosensor injection in the tissue. The response of nanosensors to systemic lithium administration (c) for three animals yields a time to maximum lithium of 14 minutes (lithium n=3, vehicle n=1).

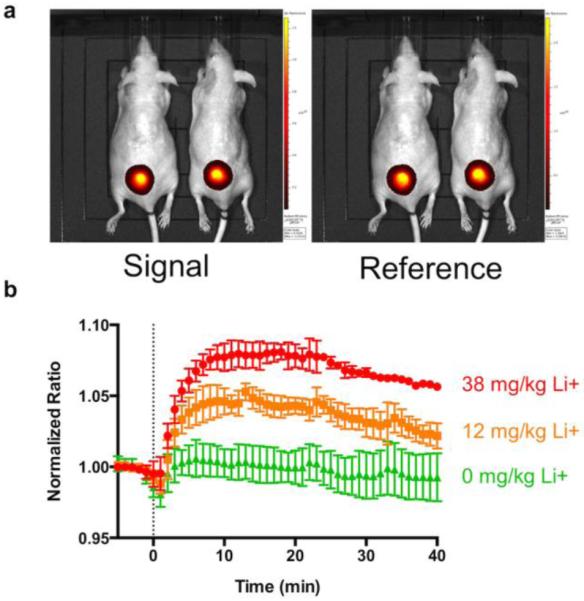

These multimodal nanosensors generate both fluorescent and photoacoustic signals which allow us to compare the two imaging modes for the sensors. Traditionally, these sensors have relied on the fluorescence of the chromoionophore directly, which is in the visible range. In this work, we shifted the fluorescence to near-IR (NIR) wavelengths to minimize optical effects from imaging in tissue (Figure 1b). To accomplish this shift, we incorporated an NIR fluorophore (DiR) into the nanosensor formulation used for photoacoustics. This dye serves as an internal reference signal and a FRET acceptor from the chromoionophore. When directly excited, the NIR intensity from DiR is not responsive to changes in lithium concentration, providing a reference signal that controls for a variety of factors, such as nanosensor number, injection depth, and sensor migration. When the chromoionophore is excited, energy transfer to DiR generates an NIR intensity that changes with lithium concentrations, because the fluorescence of the donor (chromoionophore) is responsive to lithium. When the ratio of these two signals is calculated, the resulting index is correlated with the lithium concentration and controls for other variables, similar to the photoacoustic index.

In vivo monitoring of lithium levels is drastically improved relative to traditional fluorescence imaging through the use of NIR fluorescence. Figure 4a shows example fluorescent images of mice with lithium selective nanosensors injected into their skin. Following administration of lithium via i.p. injection under the same conditions as the photoacoustic experiments above, the nanosensor fluorescence ratio increases in a dose-dependent manner to increasing systemic lithium concentrations (Figure 4b, Supporting Fig. 15-16). The time to peak concentration, 18 min, is similar to that of photoacoustics, although the magnitude of the signal change is 8% as opposed to 25% for photoacoustics at the same lithium dose, again highlighting the advantages from photoacoustic imaging and improved imaging depth even when compared with NIR fluorescent imaging.

Figure 4.

Fluorescent nanosensors for lithium yield similar results to photoacoustic nanosensors despite having a different readout mechanism. The images of both wavelengths (a) demonstrate the excellent signal to background obtained with near IR imaging, and the nanosensor measurement of absorption kinetics (b) yields a time to peak lithium of 18 min, similar to that measured with photoacoustics. The response is dose-dependent, with increases in lithium yielding higher signal. (n=3 for each lithium curve, n=6 for vehicle)

In vitro design, fabrication, and characterization of both photoacoustic and fluorescent nanosensors are essential for effective in vivo application. These steps are similar to previous reports 18 and are also detailed thoroughly in the supplementary materials (Supporting Fig. 2-14). Two key characteristics were tuned during the formulation process: sensitivity in the physiological range for lithium (0.5 – 4 mM) 29 and selectivity for the nanosensors over sodium. Sensitivity is primarily controlled through selection of the chromoionophore and the ratio of the sensor components. Selectivity is controlled through the selection of the lithium ionophore and the addition of TOPO (Trioctylphosphine oxide), which has been shown to increase lithium selectivity in macroscale optodes 20. We found a similar effect of TOPO on the selectivity of nanosensors (Supporting Fig. 2), increasing selectivity over sodium to a level suitable for monitoring changes in lithium concentration in the background of physiological sodium. As a result, changes of sodium in the physiological range do not affect the nanosensor signal. Details on tuning sensor response, final formulations, further spectral data, and additional characterization are provided in the supplementary materials. The calibration of the response to lithium for the final formulation of nanosensors in the background of physiological sodium is shown in Supporting Figure 6. The EC50 for the fluorescent sensors is 3.7 mM with a sensitivity of 45 %/log at 2 mM lithium compared with 10 mM and 29%/log for photoacoustic imaging. These results are similar, indicating that the mechanism underlying sensor response to lithium is decoupled from the readout mechanism as expected. Due to the small size of the nanosensors (27 nm by DLS, Supporting Fig. 9), the nanosensors are able to respond faster than 15 seconds (Supporting Fig. 11), significantly faster than necessary for the dynamics of lithium administration. The nanosensors are also reversible (Supporting Fig. 12), which is an essential property for in vivo monitoring so the sensors can continuously monitor increases and decreases in lithium concentration.

Discussion

This is the first report of photoacoustic imaging to measure therapeutic drug concentrations in vivo. The results show a promising improvement over fluorescence imaging of the same nanosensors and can image a depth profile with ~200 μm resolution. Imaging nanosensor injections in three dimensions solves several problems with current fluorescence-based approaches because the depth profile separately measures sensor responses in regions closest to the capillary bed. For larger molecules such as glucose, the differences between values near the capillary bed and skin surface may differ significantly 30, and photoacoustic imaging may provide superior diagnostic power. Fluorescence and photoacoustic measurements yielded the same basic response in vitro and lithium kinetics in vivo, demonstrating that the multimodal imaging does not alter the mechanism of the sensors and highlighting the robustness of the platform and earlier nanosensor development work. This validation is a key step toward the application of these nanosensors for imaging in deeper organs such as the brain.

A common limiting factor for time resolution in basic and clinical pharmacokinetic research is the need for blood sampling. This is the first in vivo real time tracking of lithium levels without blood sampling. Lithium is a common and potent treatment for bipolar disorder, but its narrow therapeutic window and low toxic dose make it more difficult to dose than other pharmaceutical therapies. A minimally-invasive continuous monitor for blood lithium concentrations would be highly useful for dose administration and management 21. Nanosensors produce a ratiometric photoacoustic index and a ratiometric fluorescent index that both respond to lithium concentrations in vivo. These multiwavelength indexes are less affected by sensor concentration and sensor injection depth than single wavelength intensity measurements, although still suffer from biases resulting from differential tissue attenuation at the two wavelengths. Commonly it is believed that shifting fluorescence wavelengths to the NIR will alleviate the effect of tissue absorption and scatter, but the improved index change from photoacoustic imaging indicates that this approach is only partially effective. In the larger context of continuous physiologic monitoring, this modular nanosensor platform translates directly to other electrolytes 16, 31 and small molecules such as histamine 17, with future work in our groups directed towards photoacoustic monitoring of these analytes with nanosensors. Additionally, this approach should work with other optical and photoacoustic imaging configurations (nonlinear optical, tomography, etc.) to obtain necessary resolution or imaging depth for particular applications outside of drug monitoring. Future work in our groups will determine the maximum penetration depth where we can image nansosensor function as well as image with higher spatial resolution. The incorporation of other imaging approaches such as SERS (surface-enhanced raman spectroscopy)32, SPECT (single-photon emission computed tomography)33, CT (computed tomography)34, MRI (magnetic resonance imaging)35, and fluorescence deconvolution36 will also yield value to these sensors.

Photoacoustic imaging is much less established than fluorescence imaging, and several technical challenges obstruct the widespread adoption of the technique. First, photoacoustic imaging instrumentation, not available in most research groups, is more complex than fluorescence imaging instrumentation. However, improved light sources and more portable imaging setups are under development, and commercial photoacoustic imaging systems are starting to appear on the market for preclinical applications 1. Current research efforts in the photoacoustics community have begun to focus on increasing the photoacoustic contrast from exogenous probes 5, 8. Future work in our groups will focus on developing nanosensors with active wavelengths in the NIR region. This will benefit both fluorescence and photoacoustic imaging by eliminating much of the background signal and enhancing sensitivity of the approach. Despite these current shortcomings, the results herein show that photoacoustics is a measurement mode for nanosensors that can provide previously unattainable measurement depths, which can have profound effects on chronic disease management.

Methods

Poly(vinyl chloride), high molecular weight (PVC), bis(2-ethylhexyl) sebacate (DOS), sodium tetrakis[3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl] borate (NaTFPB), 9-Dimethylamino-5-[4-(15-butyl-1,13-dioxo-2,14-dioxanonadecyl)phenylimino]benzo[a]phenoxazine (Chromoionophore VII;CHVII), 6,6-Dibenzyl-1,4,8-11-tetraoxacyclotetradecane (Lithium Ionophore VI; LiI VI), trioctylphosphine oxide (TOPO), tetrahydrofuran (THF), 4-(2-Hydroxyethyl)piperazine-1-ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), dichloromethane (DCM), 9-Dimethylamino-5-[4-(16-butyl-2,14-dioxo-3,15-dioxaeicosyl)phenylimino]benzo[a]phenoxazine (chromoionophore II; CHII), N,N-Dicyclohexyl-N′,N′-diisobutyl-cis-cyclohexane-1,2-dicarboxamide (Lithium Ionophore III; LiI III), 2-nitrophenyl octyl ether (NPOE), 2-nitrophenyl phenyl ether (NPPE), and lithium chloride were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). 1,2-disteroyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[methoxy(polyethylene glycol)-550] ammonium salt in chloroform (DSPE-PEG) was purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). 1,1'-Dioctadecyl-3,3,3',3'-Tetramethylindotricarbocyanine Iodide(DiR) was purchased from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY) 2-Amino-2-hydroxymethyl-propane-1,3-diol, 2M solution, (TRIS, 2M) was purchased from Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). Phosphate buffered saline (PBS with Ca++ and Mg++, pH=7.4) was purchased from Boston Bioproducts(Ashland, MA).

Nanosensor Fabrication

Protocols used in this report are based on those previously described37-38. In brief, the process of fabricating optodes and nanosensors starts with formulation of an optode cocktail comprising 500 µL THF containing PVC, DOS, and the sensing components. The ratio of these components is tuned to control the response of the nanosensors. The formulation of the nanosensors used in the manuscript is 60 mg PVC, 120 µL DOS, 20 mg TOPO, 20 mg LiI VI, 22 mg NaTFPB, and 2 mg CH VII dissolved in 1 mL of THF. The formulation for fluorescence nanosensors also includes 0.5 mg of DiR in each batch.

To fabricate nanosensors from this optode cocktail, 2 mg of DSPE-PEG (80 µL of a 25 mg/mL in chloroform) was dried in a 4 dram scintillation vial and then resuspended in 5 mL PBS with a probe tip sonicator for 30 seconds at 20% intensity (Branson, Danbury CT). 50 µL of the optode cocktail was combined with 50 µL of dichloromethane, and added to the PBS/PEG-lipid solution under probe tip sonication (3 minutes, 20% intensity). The nanosensor solution was filtered with a 0.8 µm syringe filter to remove excess polymer (Pall Corporation, Port Washington, NY). Nanosensors were sized using dynamic light scattering (DLS) with a Brookhaven 90Plus (Brookhaven Instruments, Holtsville, NY). The nanosensors were concentrated approximately 30-fold for in vivo experiments and approximately 20-fold for in vitro photoacoustic imaging using Amicon Ultra centrifugal filters (0.5 mL volume, 50 kDa MWCO, Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA). In vitro fluorescence experiments used unconcentrated nanosensors.

Fluorescent Nanosensor Characterization

Nanosensors were calibrated in vitro utilizing a Lumina II in vivo imaging system (Caliper Life Sciences, Hopkinton, MA). This plate was imaged with two channels. DiR: high lamp power, excitation filter centered at 745 nm (30 nm bandpass), emission filter from 810 nm to 875 nm, and a 1 second exposure. CHVII FRET: high lamp power, excitation filter centered at 640 nm (30 nm bandpass), emission filter from 810 nm to 875 nm, and a 1 second exposure. For data analysis regions of interest were drawn over each well using Living Image 4 software (Caliper Life Sciences) and total fluorescent intensity values were obtained for each well. The ratio of the intensities of the two channels (DiR / FRET) was calculated and then converted to alpha 23 by normalizing to the ratio obtained in the presence of 0.25 mM HCl and 0.25 mM NaOH, which set the maximum protonated and deprotonated states for the sensors. The data for the calibration curve was fit to a four parameter logistic curve using Prism 6 to determine EC50 and sensitivity.

The bulk of nanosensor formulation and screening experiments examine only the chromoionophore fluorescence rather than a ratio of two fluorescent signals. Additionally, screening experiments used 10 mM HEPES, 6 mM TRIS as the buffer solution instead of PBS. This is to enable quantification of lithium selectivity over sodium. Nanosensors were added to a 96 well plate and lithium (or sodium) solutions were then added to the wells to final concentrations of 0 mM through 1M and the plate was scanned with a Spectramax M3 plate reader. Endpoint fluorescence values were obtained at an excitation wavelength of 660 nm, emission at 705 nm, and a cutoff filter at 665 nm. In experiments where DiR was included in the formulation, fluorescence was measured with excitation:emission:cutoff at 640:780:695 for FRET and 740:780:NA for DiR fluorescence. Fluorescence spectrums were acquired using similar settings. Absorbance spectrums were taken between 400 and 850 nm.

To characterize nanoparticle diameter and morphology, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was performed on fluorescent nanosensors. Nanosensors were dried under vacuum on conductive adhesive tape attached to 25 mm aluminum SEM mounts from Electron Microscopy Sciences (Hatfield, PA). SEM images were taken using a Hitachi S4800 HRSEM operating at an accelerating voltage of 5.0 kV. Nanoparticle diameter was measured using ImageJ.

Photoacoustic System

Two photoacoustic tomography systems were used for this research. For in vitro phantom experiments, photoacoustic computed tomography (PACT) was used as previously detailed 39-40. Briefly, a tunable optical parametric oscillator laser (basiScan 120, Spectra-Physics) pumped by an Nd:YAG laser (Brilliant b, Quantel) with 10 Hz pulse repetition rate was used to excite photoacoustic waves. Light exiting the laser system was homogenized by an optical diffuser and then illuminates the sample. The photoacoustic waves were detected by a 512-element circular transducer array (Imasonic) with 5 MHz central frequency. The imaging system has 0.10 mm radial resolution and 0.10-0.25 mm tangential resolution 41. The image was reconstructed based on back projection algorithm.

For in vivo monitoring experiments, we used a deep reflection-mode photoacoustic tomography system as previously detailed 42. Briefly, a dark-field focusing illumination was achieved through a series of optical elements from the same laser source as above. The optical fluence at the animal surface was controlled to be below the maximum permissible exposure set by the American National Standards Institute 43. A photodiode (SM05PD1A, Thorlabs) was used for monitoring and compensating for the fluctuation of the laser energy. The excited ultrasound waves were detected by a 10 MHz central frequency focused ultrasonic transducer (V315, Panametrics-NDT) and the signals were then amplified by an amplifier (5072PR, Panametrics-NDT) and digitized by an oscilloscope (ZT4421, ZTEC Instruments). The imaging system was mounted on a linear translation stage (XY-6060, Danaher Motion) to acquire three-dimensional images. The spatial resolutions of the system are approximately 0.17 mm and 0.29 mm in the axial and lateral directions, respectively.

Photoacoustic In Vitro Characterization

Mixtures of nanosensors and different concentration of lithium were injected into silicone tubing. Then these pieces of tubing were sealed by rubber at both sides. The sealed tubing was embedded in agar gel and covered by chicken breast tissue for imaging. Based on these initial results, we chose imaging parameters for later in vivo imaging to minimize signal from vasculature and tissue to focus on the signal from nanosensors alone.

In Vivo Studies

All in vivo studies were approved by the institutional animal care and usage committee (IACUC) of Northeastern University. In vivo photoacoustic studies were also approved by the institutional animal care and usage committee of Washington University in St. Louis.

In Vivo Photoacoustic Studies

The mice used in this research were Hsd:Athymic Nude-Foxn1nu from Harlan Laboratories. Photoacoustic imaging experiments were conducted using the system described above. Animals were anesthetized with 1.5% isoflurane in oxygen and 40 µL of nanosensors were injected i.d. into the mouse on the back. The animals were imaged with two channels at excitation wavelengths 515 nm and 660 nm (the peak wavelengths for the PA signal). Baseline raster scan images were acquired at both wavelengths and continuous monitoring was done with both wavelengths at the center of the nanosensor injection. Data points were acquired approximately every minute after an i.p. injection of 38 mg/kg lithium (administered as lithium chloride in PBS, experimental) or a matching volume of PBS (control). Images were acquired every minute for approximately one hour. Animals were imaged one at a time. All animals were sacrificed after experiments were completed. For data analysis of each experiment, an index of the two photoacoustic intensities was generated by dividing the 515 nm signal by the 660 nm signal. These ratios were normalized to that at the first time point after injection of lithium. These data were linearly interpolated to align time and intensity points before averaging. Error bars for lithium dataset represent the standard deviation of three animals.

Fluorescent in vivo Studies

The mice used in this research were male SKH1-E Nude mice from Charles River (Wilmington MA). Fluorescent imaging experiments were conducted using a Lumina II in vivo imaging system (IVIS). Animals were anesthetized with 2.25% isoflurane in oxygen and placed in the animal imager. 30 µL of nanosensors were injected i.d. into the mouse on the back. The animals were imaged with two channels. DiR: high lamp power, excitation filter centered at 745 nm (30 nm bandpass), emission filter from 810 nm to 875 nm, and a 1 second exposure. CHVII-FRET to DiR: high lamp power, excitation filter centered at 640 nm (30 nm bandpass), emission filter from 810 nm to 875 nm, and a 1 second exposure. Baseline images were acquired for approximately 30 minutes, followed by an i.p. injection of 12 or 38 mg/kg lithium (administered as lithium chloride in PBS, experimental) or a matching volume of PBS (control). Images were acquired every minute for approximately one hour. The imaging equipment could not image six animals simultaneously, so animals were imaged in pairs. All animals were sacrificed after experiments were completed. For data analysis of each experiment, a region of interest encompassing the injection area was selected and total fluorescent intensity for each channel was recorded. At each time point an index was generated by dividing the intensity from DiR channel by the CHVII-FRET channel. These ratios were normalized to the first time point before injection of lithium. This data was then averaged together across three experimental animals for each lithium concentration and six control animals using linear interpolation to align time and intensity points before averaging. Error bars represent the standard deviation of these animals.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by the NIBIB under award number F32EB015270 (to K.J.C.), the NIGMS under award number R01 GM084366 (to H.A.C.), the NINDS under award number R01 NS081641 (to H.A.C.), and the National Institutes of Health grants DP1 EB016986 (NIH Director’s Pioneer Award, L.V.W.), R01 CA186567 (NIH Director’s Transformative Research Award, L.V.W.), R01 CA157277 (L.V.W.). L.V.W. has a financial interest in Microphotoacoustics, Inc. and Endra, Inc., which, however, did not support this work.

We would like to thank several other researchers for their contributions. C. Kakidas assisted with initial lithium nanosensor formulation and M. R. Chatni made initial photoacoustic measurements. L. Li assisted with setting up the photoacoustic imaging system. C. G. Skipwith acquired SEM images of the nanosensors. C. G. Skipwith and T. T. Ruckh carefully read the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Additional information on optimization and in vitro characterization of nanosensors as well as full datasets for in vivo experiments are presented ad supporting information. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wang LV, Hu S. Photoacoustic Tomography: In Vivo Imaging from Organelles to Organs. Science. 2012;335:1458–1462. doi: 10.1126/science.1216210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim C, Favazza C, Wang LV. In Vivo Photoacoustic Tomography of Chemicals: High-Resolution Functional and Molecular Optical Imaging at New Depths. Chemical Reviews. 2010;110:2756–2782. doi: 10.1021/cr900266s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang LV. Multiscale photoacoustic microscopy and computed tomography. Nature Photonics. 2009;3:503–509. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2009.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang L, Maslov K, Wang LV. Single-cell label-free photoacoustic flowoxigraphy in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:5759–5764. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215578110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de la Zerda A, Bodapati S, Teed R, May SY, Tabakman SM, Liu Z, Khuri-Yakub BT, Chen X, Dai H, Gambhir SS. Family of Enhanced Photoacoustic Imaging Agents for High-Sensitivity and Multiplexing Studies in Living Mice. Acs Nano. 2012;6:4694–4701. doi: 10.1021/nn204352r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu W, Huang Q, Ku G, Wen X, Zhou M, Guzatov D, Brecht P, Su R, Oraevsky A, Wang LV, Li C. Photoacoustic imaging of living mouse brain vasculature using hollow gold nanospheres. Biomaterials. 2010;31:2617–2626. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cook JR, Frey W, Emelianov S. Quantitative Photoacoustic Imaging of Nanoparticles in Cells and Tissues. Acs Nano. 2013;7:1272–1280. doi: 10.1021/nn304739s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taruttis A, Morscher S, Burton NC, Razansky D, Ntziachristos V. Fast Multispectral Optoacoustic Tomography (MSOT) for Dynamic Imaging of Pharmacokinetics and Biodistribution in Multiple Organs. Plos One. 2012:7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chatni MR, Yao J, Danielli A, Favazza CP, Maslov KI, Wang LV. Functional photoacoustic microscopy of pH. Journal of Biomedical Optics. 2011:16. doi: 10.1117/1.3644495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ray A, Yoon HK, Lee YEK, Kopelman R, Wang X. Sonophoric nanoprobe aided pH measurement in vivo using photoacoustic spectroscopy. Analyst. 2013;138:3126–3130. doi: 10.1039/c3an00093a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pu K, Shuhendler AJ, Jokerst JV, Mei J, Gambhir SS, Bao Z, Rao J. Semiconducting polymer nanoparticles as photoacoustic molecular imaging probes in living mice. Nature Nanotechnology. 2014;9:233–239. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2013.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ray A, Rajian JR, Lee Y-EK, Wang X, Kopelman R. Lifetime-based photoacoustic oxygen sensing in vivo. Journal of Biomedical Optics. 2012:17. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.17.5.057004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chatni MR, Xia J, Sohn R, Maslov K, Guo Z, Zhang Y, Wang K, Xia Y, Anastasio M, Arbeit J, Wang LV. Tumor glucose metabolism imaged in vivo in small animals with whole-body photoacoustic computed tomography. Journal of Biomedical Optics. 2012:17. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.17.7.076012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dubach JM, Das S, Rosenzweig A, Clark HA. Visualizing sodium dynamics in isolated cardiomyocytes using fluorescent nanosensors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:16145–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905909106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Aberasturi DJ, Montenegro JM, de Larramendi IR, Rojo T, Klar TA, Alvarez-Puebla R, Liz-Marzan LM, Parak WJ. Optical Sensing of Small Ions with Colloidal Nanoparticles. Chem. Mat. 2012;24:738–745. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dubach JM, Zhang N, Lim E, Francis KP, Clark HA. In vivo sodium concentration continuously monitored with fluorescent sensors. Integrative Biology. 2011;3:142–148. doi: 10.1039/c0ib00020e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cash KJ, Clark HA. Phosphorescent Nanosensors for in Vivo Tracking of Histamine Levels. Analytical Chemistry. 2013;85:6312–6318. doi: 10.1021/ac400575u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cash KJ, Clark HA. In vivo histamine optical nanosensors. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland) 2012;12:11922–32. doi: 10.3390/s120911922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Billingsley K, Balaconis MK, Dubach JM, Zhang N, Lim E, Francis KP, Clark HA. Fluorescent nano-optodes for glucose detection. Anal Chem. 2010;82:3707–13. doi: 10.1021/ac100042e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coldur F, Andac M. All-Solid-State Polyvinyl Chloride Membrane Lithium-Selective Electrode with Improved Selectivity and Its Application in Serum Lithium Assay. Sensor Letters. 2011;9:1738–1744. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Belmaker RH. Medical progress: Bipolar disorder. New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;351:476–486. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra035354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buhlmann P, Pretsch E, Bakker E. Carrier-Based Ion-Selective Electrodes and Bulk Optodes. 2. Ionophores for Potentiometric and Optical Sensors. Chem Rev. 1998;98:1593–1688. doi: 10.1021/cr970113+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bakker E, Buhlmann P, Pretsch E. Carrier-Based Ion-Selective Electrodes and Bulk Optodes. 1. General Characteristics. Chem Rev. 1997;97:3083–3132. doi: 10.1021/cr940394a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kimura K, Yano H, Kitazawa S, Shono T. Synthesis and selectivity for lithium of lipophilic 14-crown-4 derivatives bearing bulky substituents or an additional binding site in the side arm. Journal of the Chemical Society-Perkin Transactions. 1986:1945–1951. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bell AG. On the production and reproduction of sound by light. American Journal of Science. 1880;20:305–324. Series 3. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nciri R, Allagui MS, Croute F, Vincent C, Elfeki A. Effects of low doses of Li carbonate injected into mice. Functional changes in kidney seem to be related to the oxidative status. Comptes Rendus Biologies. 2008;331:23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keck PE, McElroy SL. Clinical pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of antimanic and mood-stabilizing medications. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2002;63:3–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wood AJ, Goodwin GM, Desouza R, Green AR. The Pharmacokinetic profile of lithium in rat and mouse - An important factor in psychopharmacological investigation of the drug. Neuropharmacology. 1986;25:1285–1288. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(86)90149-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Citterio D, Takeda J, Kosugi M, Hisamoto H, Sasaki S.-i., Komatsu H, Suzuki K. pH-independent fluorescent chemosensor for highly selective lithium ion sensing. Analytical Chemistry. 2007;79:1237–1242. doi: 10.1021/ac061674g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kovatchev BP, Shields D, Breton M. Graphical and numerical evaluation of continuous glucose sensing time lag. Diabetes technology & therapeutics. 2009;11:139–43. doi: 10.1089/dia.2008.0044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ruckh TT, Mehta AA, Dubach JM, Clark HA. Polymer-Free Optode Nanosensors for Dynamic, Reversible, and Ratiometric Sodium Imaging in the Physiological Range. Sci. Rep. 2013:3. doi: 10.1038/srep03366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang YQ, Yan B, Chen LX. SERS Tags: Novel Optical Nanoprobes for Bioanalysis. Chemical Reviews. 2013;113:1391–1428. doi: 10.1021/cr300120g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brinkhuis RP, Stojanov K, Laverman P, Eilander J, Zuhorn IS, Rutjes FPJT, van Hest JCM. Size Dependent Biodistribution and SPECT Imaging of In-111-Labeled Polymersomes. Bioconjugate Chemistry. 2012;23:958–965. doi: 10.1021/bc200578s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xi D, Dong S, Meng X, Lu Q, Meng L, Ye J. Gold nanoparticles as computerized tomography (CT) contrast agents. Rsc Advances. 2012;2:12515–12524. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chan KWY, Liu G, Song X, Kim H, Yu T, Arifin DR, Gilad AA, Hanes J, Walczak P, van Zijl PCM, Bulte JWM, McMahon MT. MRI-detectable pH nanosensors incorporated into hydrogels for in vivo sensing of transplanted-cell viability. Nature Materials. 2013;12:268–275. doi: 10.1038/nmat3525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sarder P, Nehorai A. Deconvolution methods for 3-D fluorescence microscopy images. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2006;23:32–45. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dubach JM, Balaconis MK, Clark HA. Fluorescent nanoparticles for the measurement of ion concentration in biological systems. Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE. 2011 doi: 10.3791/2896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dubach JM, Harjes DI, Clark HA. Fluorescent ion-selective nanosensors for intracellular analysis with improved lifetime and size. Nano Lett. 2007;7:1827–31. doi: 10.1021/nl0707860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xia J, Chatni MR, Maslov K, Guo Z, Wang K, Anastasio M, Wang LV. Whole-body ring-shaped confocal photoacoustic computed tomography of small animals in vivo. Journal of Biomedical Optics. 2012:17. doi: 10.1117/1.JBO.17.5.050506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gamelin J, Maurudis A, Aguirre A, Huang F, Guo P, Wang LV, Zhu Q. A real-time photoacoustic tomography system for small animals. Optics Express. 2009;17:10489–10498. doi: 10.1364/oe.17.010489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xia J, Guo ZJ, Maslov K, Aguirre A, Zhu Q, Percival C, Wang LHV. Three-dimensional photoacoustic tomography based on the focal-line concept. Journal of Biomedical Optics. 2011:16. doi: 10.1117/1.3625576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Song KH, Wang LV. Deep reflection-mode photoacoustic imaging of biological tissue. Journal of Biomedical Optics. 2007:12. doi: 10.1117/1.2818045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Institute ANS. In American National Standard for Safe Use of Lasers - ANSI Z136.1-2007. Laser Institute of America; 2007. American National Standard for Safe Use of Lasers - ANSI Z136.1-2007. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.