Abstract

To better understand psychosocial distress in veterans treated for cancer, these researchers conducted a series of 3 focus groups. Emerging themes suggest that cancer survivorship is a process, and interventions need to be tailored to each patient.

There are > 1/2 million veterans who receive care in the VHA who have completed treatment for cancer.1 Long-term consequences of cancer treatments across physiological, psychological, and social domains often persist into survivorship.2 Completion of treatment is a pivotal point marking a new phase of health care. Psychosocial distress screening is recommended at such pivotal points, including diagnosis and transitions between or off treatment.3 Increased coordination and communication between patients, oncologists, and primary care providers (PCPs) is needed to identify and treat psychosocial distress.4

Most research focuses on middle-aged female breast cancer survivors. Limited data suggest that veterans, like other groups studied, may experience depression, cancer-specific worry, and cancer-related posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after cancer treatment.5 Veterans’ combat exposure, higher rates of combat-related PTSD, and multiple morbidities may impact their coping with such distress.6

In caring for cancer survivors, 2 key roles for PCPs, in addition to comorbidity management, are (1) psychological distress support; and (2) behavior modification counseling (eg, weight, smoking, goal setting).7 Yet, community-based PCPs report difficulty addressing emotional distress and fears in cancer survivors that present during office visits.8 Studies of the validity of the “distress thermometer,” an efficient screen for distress, are mixed.9–11

We conducted a series of 3 focus groups to better understand psychosocial distress in veterans treated for cancer, to capture the complexity of distress and resiliency in the veteran experience. Focus groups placed particular emphasis on stress-related symptoms associated with cancer (ie, worries, fears) as well as the meaning ascribed to the cancer in changed values and beliefs. Emerging themes suggest opportunities for distress screening during encounters with PCPs in their expanding role within the VA Patient-Aligned Care Team (PACT), as well as referral to social and behavioral health specialists.

METHODS

Participants and Recruitment

Participants were recruited through the VA Boston Tumor Registry or in hospital waiting areas. Interested veterans were contacted by the research coordinator who explained the study and screened those patients who met the study criteria: (1) ≥ aged 18 years; (2) diagnosed with cancer other than basal cell carcinoma; (3) patients who completed treatment within the past 36 months; and (4) patients with no primary diagnoses of dementia, substance dependence (active), or psychotic disorder(s).

Procedures

Forty-eight veterans completed individual interviews consisting of standardized mental health and quality-of-life measures, as previously described.6 Of these, 14 participants were purposively sampled to attend 1 of 3 focus groups based on interviewer’s nomination and participant availability. Participants were compensated $30 for taking part in the study. The study was reviewed and approved by the VA Boston Healthcare System and Harvard Medical School Institutional Review Boards; all study procedures occurred at the VA following informed consent.

Focus Groups

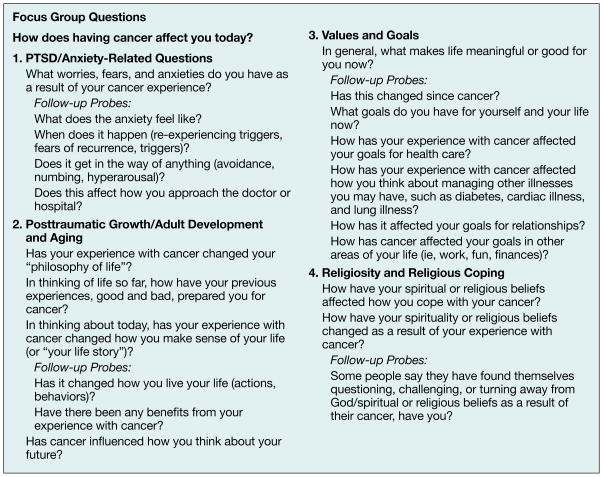

A semistructured format was used based on established recommendations.12,13 Each group began with an open question, “How does having cancer affect you today?” followed by specific questions in 4 psychosocial domains: (1) PTSD/anxiety; (2) post-traumatic growth; (3) values/goals; and (4) religious/spiritual coping or meaning making (Figure 1). Focus groups were led by 2 clinically trained moderators: A social worker or psychologist. A research technician was also present to monitor recording equipment and take notes.

Figure 1.

Focus group questions.

Analysis

Focus group recordings were transcribed by the research technician before analyses proceeded in accordance with an iterative coding approach to content analysis.14 Three members of the investigative team independently read and coded transcript data to minimize bias in analyses. A common method of reference was developed after initial readings to ensure that emerging themes could be compared across raters. Next, in-depth coding of each transcript was conducted by 1 of the 3 coders, who focused on identifying detailed thematic codes. An independent audit by another investigator then examined thematic codes across groups for content and completeness. Discrepancies between the initial analysis and the independent audit were resolved through consensus agreement during weekly meetings. Through this iterative process, a set of themes was agreed on by the investigative team and confirmed by a final independent audit by a senior investigator. All common themes were observed across all 3 focus groups suggesting saturation.

RESULTS

Sample and Coding Results

The mean age of focus group participants was 66.21 years (SD = 9.20), range of 57 to 86. Participants were predominantly white, all were men, and 6 had previous combat experience. Participants had a variety of cancers, and a variety of treatments were represented across the groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of focus group participants (N = 14)

| Characteristics | Value |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 66.2 (9.20) |

| Months since treatment, mean (SD) | 13.7 (13.0) |

|

| |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | |

| White | 13 (92.9) |

| Black/African American | 1 (7.1) |

|

| |

| Education, n (%) | |

| Some high school | 1 (7.1) |

| High school diploma | 2 (14.3) |

| Some college or college degree | 9 (64.3) |

| Postgraduate courses or degree | 2 (14.3) |

|

| |

| Combat experience, n (%) | 6 (42.9) |

|

| |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | |

| Bladder | 1 (7.1) |

| Chronic lymphocytic leukemia | 1 (7.1) |

| Colon | 3 (21.4) |

| Esophageal | 1 (7.1) |

| Eye | 1 (7.1) |

| Lymphoma | 2 (14.3) |

| Multiple myeloma | 1 (7.1) |

| Prostate | 3 (21.4) |

| Throat | 1 (7.1) |

|

| |

| Treatment,a n (%) | |

| Surgery | 8 (57.10) |

| Radiation | 4 (28.6) |

| Chemotherapy | 6 (42.9) |

Four individuals had ≥ 2 of these treatments.

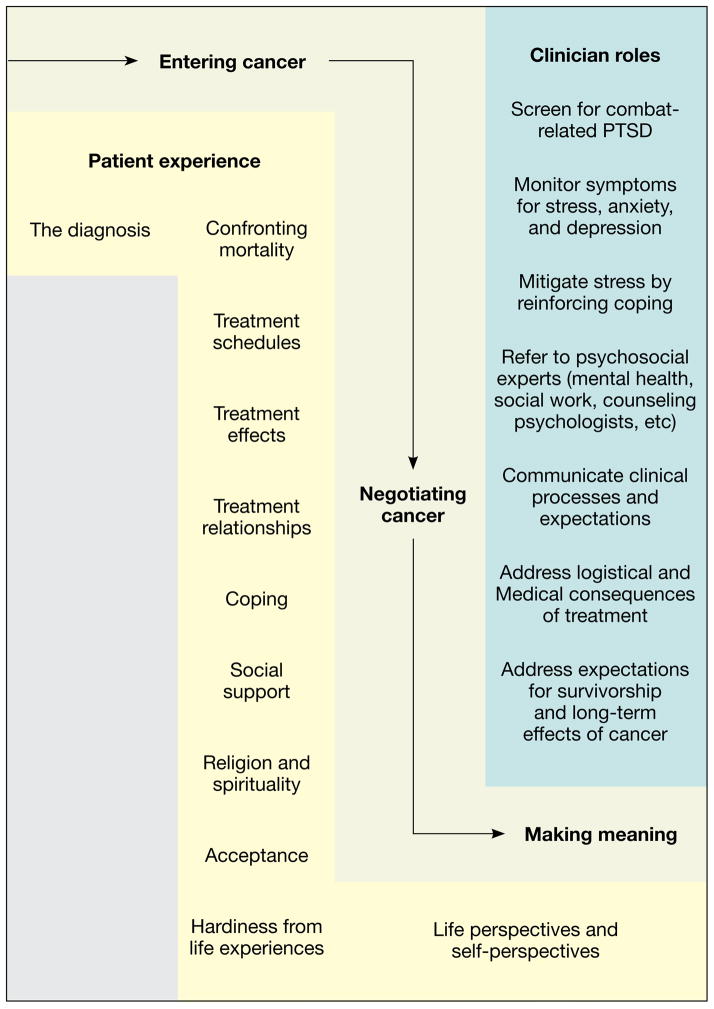

A total of 288 thematic codes or independent units of meaning were observed across the 3 focus groups. These codes were organized into 12 broader themes, which fell into 3 overarching categories: (1) entering cancer; (2) negotiating cancer; and (3) transforming meaning through cancer (illustrated in Figure 2). Examples of each theme follow and appear in Table 2. Experiences unique to military veterans were present throughout these themes. Abbreviations are used to indicate which participant is being quoted (ie, P1 for Participant 1).

Figure 2.

Veterans’ psychosocial experiences of cancer care.

Table 2.

Twelve themes with exemplar participant responses

| Entering cancer: Facing diagnosis and treatment | |

| 1. The diagnosis | “I think about it every day. Every single day.” (P1) “I had 4 days by myself in Boston…and I would go sit down and the tears would just roll. I called my counselor back home the second day, and he said get a counselor down there, which helped. It was really bad.” (P12) |

| 2. Confronting mortality | “I want to die a good man. When I wake up in the morning, I ask God to keep me awake…if I had to stand in front of the gates now, I did a lot of nasty, nasty things when I was younger, but I believe I’ve been forgiven. And that’s what I look forward to, a nice peaceful death, and the ride, and the white light, or whatever. I believe there is a re-uniting with my family and my loved ones.” (P9) I don’t make very big plans too far down the road because of what goes on with the type of cancer I have. I mean they can say I’m cured and all that, but I know what’s going on. I know what I feel. I feel like I’ve been run over and stomped on.” (P6) |

| 3. Treatment schedules | “I open up my pillbox in the morning, I don’t have to have breakfast! It’s like Kix, ya know.” (P4) “All of a sudden you are diagnosed, then you are expected to be your own advocate. To get going and know what’s going on and what the doctor says and all of that…my suggestion would be to actually have classes for people who are new to everything. How could you be your own advocate? Because that could be a real big help….” (P12) |

| 4. Treatment effects | “It’s never ending…the fear is [cancer] is lurking here somewhere, and it’s going to pop up.” (P5) “All of us have had a lot of different experiences that brought us to the point where we cope with this insanity that we’ve got. And that’s what I call it. Insanity. I hate it. I hate it.” (P1) |

| 5. Treatment relationships | “Then we started talking about cancer… and I said, Am I gonna die from this? Do you think I’ll die from this?… so she [the doctor] looked at me and she says, I’ll put it this way, and it sticks, everyday I think about it, she says, you may not die from it but you’ll die with it. And I said thanks…she told me the facts right there.” (P6) “My PC on the outside [of the VA] who I have been seeing for over 20 years, and he’s in recovery also which really brought us tighter, he’s a super nice guy…if there’s one person on this earth that I’m going to put my life in their hands, it’s him. I had that much faith in the man.” (P9) |

| Negotiating cancer: Finding a passage through | |

| 6. Coping | “Good times are like taking an aspirin. You can have a good time if it picks you up for that particular hour, or day, or whatever. But bad times, I think you learn to avoid them as much as possible.” (P4) “They suggested that I take a prostate test, and the colon, that kind of thing, and I kind of put up a wall. After everything I had been through with the treatments, I didn’t want to hear. I’m not ready for it, I guess…I’ve had enough needles. I’ve had enough treatments. Maybe down the road somewhere, but I don’t, like, want to go from one thing to the next.” (P14) |

| 7. Social support | “[T]his old Portuguese woman, I never even knew her, put her hand on my shoulder and pulled me aside…and she said don’t you dare walk out of here,… she says, I have a daughter in here getting treated for breast cancer–full breast, and I lost a son 4 years ago to cancer. I have a husband at home with cancer. And I thought, oh gee, what can I say to her. She said sit down and wait for your damn ass to be called in the room. That’s just what she said to me…. After that, my outlook changed.” (P6) “My father, all the time, he’s saying, just 1 day at a time…It didn’t hit home, but now it’s reality…it’s this day, it’s this time, and that’s it. I just try to concentrate on that, focus on where I’m at and what I’m doing, try to be the best person I can be and enjoy.” (P14) |

| 8. Religion and spirituality | “I’m probably more spiritual…. I would be lying if I said that I wasn’t. I have a friend who is very connected with angels. And when I was in surgery, she was in Florida, and she actually sent me a little stuffed angel.” (P10) “It reinforced my faith is what it did. I didn’t have any fear when I got it [cancer], and I understand why I didn’t have any fear. I believe there’s a higher power out there for me, and it reinforced it.” (P11) |

| 9. Acceptance | “Well, this is just another chapter in your life story. It’s an inescapable one–you got it, you’re not going to change it.” (P8) “I had some regrets…. Maybe that’s why I got it…. I know I shouldn’t have picked up them cigarettes. But then, you know, it’s too late. It is what it is, and now I just deal.” (P14) |

| 10. Hardiness from life experience | “[Y]ou came here for 16 years for anxiety and PTSD,… but now you are facing cancer like its nothing. I said, well, cancer I can deal with because I know what it is–it’s cancer. How worse can it get?…I’ve dealt with so much, what’s another thing? It’s just cancer.” (P6) “[I]n the military, we were in, Nam…I was in a special operating group, and I put myself in a crappy situation 1 time. I’m on the horn [with the officer], and I said, situation is hopeless. He had to get us out. And he said to me, if the situation is hopeless, there is nothing to worry about, click. And that did more to prepare me for when they said you have cancer, its growing fast, we’ll do what we can. I just heard that man’s voice, and I said okay, you gotta dig right in here because if it’s hopeless, he was right, there is nothing to worry about.” (P5) |

| Meaning making: Changing perspectives of life and oneself | |

| 11. Life perspectives | “It’s changed my life to the point where I called my boss and said I can’t build boats for a year. Why not, why? And I told him. He said take 2 years if you need it. It’s affected my life. I want to get rid of it.” (P2) “I look at it [life after cancer] as you continue on with your normal things. That you’re not handicapped as other people are, ya know? That I continue on with my everyday way of life.” (P13) |

| 12. Self-perspectives | “I’ve become a great father and a great grandfather, while maybe before I was just an average father.” (P5) “It’s a word—Cancer. You never associate it with you. I think that sometimes when I say to myself, What was it like before cancer, what did I feel like, what was I thinking all the time, did I even think about anything? I don’t remember, it’s like you dwell more on it every day with cancer. You make the most of it and you do what you have to do.” (P6) |

Entering Cancer: Facing Diagnosis and Treatment

The diagnosis

Participants across groups reflected on the shock of hearing the initial diagnosis: “It is like branded in your brain. As soon as they say that Big C, that’s it. Anybody who is not in your shoes, they say, ah you can probably put it out of your mind, but no way in hell.” (P4) Previous combat experiences tempered diagnosis distress: “It didn’t bother me. Hey, I was in the South Pacific for 4 years…that was the worst part.” (P7) But previous combat experiences could also exacerbate it, “When I was first diagnosed, a lot of Vietnam came back…a little stronger.” (P6)

Confronting mortality

Across cancer type, severity, and age, diagnosis and the evolving experience with cancer served as a reminder of mortality. For some, this manifested in a reprioritization of goals: “It’s the point in your life when you start looking back at all these life experiences, you know, and you start to realize there’s a lot of people you could help out. There’s a lot of things you can teach.” (P8) Others expressed a more resigned attitude: “I hate to say it, but I know what’s going to happen. I know the end result of this, how you die. I looked it up, I’ve read it, so I know what I’m in for.” (P6) Many focused on their hopes for an afterlife or uncertainty about the hereafter: “It’s not knowing. I’m going to leave here—I don’t know what’s going to happen. I don’t know what’s out there. I just don’t know, so I live with it.” (P11)

Treatment schedules

A sense of feeling overwhelmed by medical appointments was expressed across most groups. “This week I was at 5 different doctors in 5 days. That can get really tiresome.” (P3) Others focused on the number of medications they were receiving or fears associated with follow-up visits as the primary burden: “I’ve had more medical visits in the last 2 years than I’ve had my whole life. I mean I’m being X-rayed and all the X-rays are traumatic to me, because you don’t know what the hell they are going to find….” (P6)

Treatment effects

The experience of a cancer diagnosis and treatment caused distress and exacerbated pre-existing medical and mental health conditions: “[Cancer] affected my mood quite a bit, even though I didn’t notice it. My wife has said it. She has never known me to get upset in 24 years, or maybe I should say angry…. I do know there has been a lot of flashbacks with the PTSD in Vietnam, since the cancer.” (P3) Others indicated that cancer was another stressor added to their list of medical concerns: “I suffer from depression and PTSD, so my list is long, but this cancer has me so messed up….” (P1) One veteran summarized a frequently expressed view by saying: “If the disease doesn’t get you, the cure might.” (P8) Others focused on pain, discomfort, or functional losses (eg, incontinence, impotence): “…sexual function—I never know if it works, and that bothers me. I’ve been with my wife for 34 years.” (P9)

Treatment relationships

Numerous veterans quoted their health care providers, revealing the impact patient-provider interactions have: “This young doctor looked like he was afraid, said he had some bad news for me. He said, you have stage 3 cancer and it’s spreading real fast.” (P5) Others described perceived distinctions between VA hospitals and independent hospitals or their decision to seek care in one setting vs the other. One veteran reported, “I’m surprised at the VA doctors. I didn’t expect them to be as good as they are.” (P1) Some noted the role of financial motivations for care: “These people are making money like it’s going out of style.” (P5) Feelings of disappointment, frustration, and anger toward clinicians were expressed in more overt ways as well: “Sometimes you have to squeeze your doctors…it’s almost like it’s a lethal cross examination when you’re speaking with your physician…I don’t know if they’re afraid to get sued, or what’s the story.” (P5)

NEGOTIATING CANCER: FINDING A PASSAGE THROUGH COPING

Although explicit references to “coping” were rare across groups, many discussed behaviors and attitudes used to cope: “I’ve always looked at the positive more than the negative…it’s a roller coaster. You enjoy the good times, and you get through the bad times, whether it’s the Big C or something else.” (P3) Others used humor, which also appeared within group discussions: “I try to look at the light side of it. I’ve saved a lot of money on haircuts and shaving cream when going through the chemo. The benefits were more than I expected!” (P8) Some acknowledged less effective coping strategies, such as avoidance or denial: “I’m told at this stage, at the age that you are, you should be having it checked out…. And that appointment was cancelled with the eyes, and I am just letting it go for a while. Ya know, being lackadaisical about it, because I don’t know. Deep down, I just don’t want to deal with anything right now.” (P14)

Social Support

Veterans described family, friends, and strangers as both a unifying force and one that fosters isolation: “The family is coming together in a lot of different ways. They’re offering to accompany me to my chemo sessions. The family is getting back together as a result of my cancer diagnosis.” (P1) “It certainly quiets them once they find out, Oh, you have cancer. Then you don’t hear from them anymore. It tends to isolate you in a lot of ways.” (P8) Disclosure of a shared diagnosis was also discussed: “I had prostate cancer. It’s a secret among men until it’s shared. I’ve met 5 to 7 people in the last year. Some of them I’ve known for years, and I never knew they had prostate cancer. And suddenly, I did that. Another guy speaks up, oh, I had that… we don’t talk about it as a conversation at breakfast, but…It’s nice.” (P10)

Religion and Spirituality

Coping through religious practices or belief in a higher power was endorsed frequently. Veterans discussed a higher power as they searched for indicators of the etiology or a reason that they got cancer: “I don’t blame God…I don’t think he did it…I don’t think it had anything to do with religion.” (P8) Others cited spirituality as a source of hope: “I am not afraid of this thing, like I said, I am hoping for divine intervention.” (P1) Some reported decreased spirituality: “I’m probably less spiritual than I was before, only because I am just fed up with everything—all the religions as they are. And I don’t think any of them are quite right, but I am still searching.” (P12) Others noted an increase in spirituality: “I thought I was doing good in the spiritual world, but when I got the cancer, and it hit me…just that borderline life and death, started me talking to God a lot…. It’s enhanced my beliefs and spirituality.” (P14)

Acceptance

Predestination and the inevitability of events were voiced by several veterans as they discussed attempts to make sense of their diagnosis. These beliefs were attributed to their time in the service: “You don’t know where you’re going to be sent. You don’t know what tomorrow’s going to bring. And I’ve got to live through whatever, whether it’s combat or…an accident…if it’s meant to be, it’s going to be meant to be…I think it hardened me in a sense, being a military person.” (P13) Throughout discussions, acceptance in the unknown and the unpredictability of life’s events emerged: “I think anyone who is in the service has to be a fatalist…he doesn’t understand why he didn’t get shot. You can ask all the questions in the world but you’re not going to get any answers.” (P4) For many, searching for answers (ie, “why me”) seemed to be central to negotiating cancer, while others emphasized luck, chance, and lack of control: “I am out of control. I can’t even attack it. I can’t do anything… [before the operation] I worked out 5 days a week in the gym. When I got out of the hospital, I looked like I had been in a concentration camp.” (P6)

Hardiness From Life Experience

Group members almost universally discussed cancer survivorship in the context of a broader life experience. For example, other illnesses (eg, diabetes, congestive heart failure), the experience of providing care for dying parents, and military experiences contributed to coping: “I had a lot of troubles. I had booze problems, drug problems over the years and early on. Ya know, I had been through a lot. But when I got the cancer, I think all of those experiences really helped me.” (P14) Others felt that age offered context: “I had it when I was 85, you know. I’ve been through all that stuff before to get to where I am, and I thank God I’m that way.” (P7)

MEANING MAKING: CHANGING PERSPECTIVES OF LIFE AND SELF

Life Perspectives

Participants discussed a variety of perspectives about change. Some participants described a shift to more exciting, meaningful, or important pursuits: “I started driving my motorcycle over 100 miles per hour, I started parachuting again, I was living my life [before cancer], but I was living it maybe in a way that wasn’t much fun.” (P5) In contrast, others discussed wishes to fulfill a variety of life aspirations (eg, starting a Cub Scout troop, being a better father). Almost all veterans discussed an increased appreciation for life and reduced concern over trivial matters: “The incidental things don’t bother you anymore, you just put them aside. I don’t even want to listen to them…. It’s like nonsense.” (P4) “I want to feel every moment I have left right now as best I can.” (P3).

Self-Perspectives

A modified self-concept—psychological, physical, and social—was a focus for many: “I think of it as very emasculating…. It is mind blowing that sexually, I can’t do anything.” (P3) Others commented on wearing incontinence briefs and carrying supplies with them in a bag like a woman. However, not everyone reported changes in self-concept or how others viewed them: “My friends know I lost an eye, but they also treat me just as a normal person who has an eye that’s missing. No big deal.” (P12) Regarding body image, several reported a disconnect between their physical appearance and how they felt. Others described equating the questions, “How are you doing?” with “What is your medical status?” in interactions with others. One veteran reported that the medical community treats him differently: “Once you have cancer, I don’t know if stigmatize is the right word…the minute you tell them you have cancer—okay, now you are a whole different class of human being. If you come in and say you have a cough, then they X-ray it right away. It’s like the medical profession now is saying you’re different.” (P5) Most voiced feeling that cancer was a permanent aspect of life: “I don’t think you ever get rid of it personally. I think it’s still with you regardless, it just settles down and it pops its head back up.” (P6) Finally, discussions revealed differing perspectives on identification as a “cancer survivor”: “I want to be one of those people on TV, I’m telling you, when I go home today…. They’re going to have these 30-year survivors on the screen, and I want to be one of them.” (P1) A veteran in a different group disagreed: “I don’t consider myself a cancer survivor…when I see those ads on TV, cancer survivor, I know I did that—but somehow [I’m] not living there, I just don’t look at it that way.” (P10)

DISCUSSION

This paper describes 12 themes that emerged from focus group data with military veterans discussing the experience of cancer in their lives. Their voices alone can in no way represent the more than 500,000 cancer survivors within the VHA, but do articulate the psychosocial complexities patients face when receiving cancer care. Like other cancer survivors, these veterans described wide-ranging effects of cancer across physical, psychological, social, and spiritual domains, as they traveled from diagnosis, through treatment, and into survivorship and recovery (Figure 2).15,16 Coping was affected by intra- and interpersonal factors, as well as the interaction with the health care system.

Unique to the veteran experience is the report that symptoms of combat-related PTSD surface or worsen during the stressors of cancer. Depression, anxiety, and cancer-related PTSD are acknowledged comorbidities that arise not infrequently during cancer diagnosis and treatment.6 Combat-related PTSD can further complicate the veterans’ capacity to negotiate cancer and obtain treatment for mental conditions. Thus, increased screening at the time of cancer diagnosis and throughout the trajectory of care for clinically significant depression, anxiety, or cancer-specific PTSD symptoms, or exacerbations of preexisting mental health conditions (eg, combat-PTSD, substance use disorders) may be warranted. When time and resources permit, brief interactions with family members or other collaterals during the cancer treatment and recovery stages can help provide information about the veteran’s behavior at home or distress within the family system that may benefit from a referral.

In our conceptualization of veterans’ psychosocial experiences within cancer care (Figure 2), we describe potential clinician roles to address emotional distress. These roles include screening for symptoms of distress (depression, anxiety, and stress), mitigating distress by reinforcing the use of positive coping strategies noted in this article (eg, hardiness gained in combat and other life experiences), and referring patients for interventions as described in Table 3. For patients in immediate distress, providing opportunities to elicit patient preferences may be indicated for: (1) follow-up tests needed for surveillance; (2) discussion of rehabilitation potential (eg, incontinence, impotence, etc); and (3) when providing education about healthy behaviors. Sensitivity to perceived stigma (eg, being treated differently because of a cancer history) may also prevent miscommunications or patient misperceptions of providers’ motives.

Table 3.

Possible patient concerns and referral resources17

| 1. Psychosocial distress screening and referral | |||

| After cancer treatment you may feel depressed, anxious, or have nightmares of cancer. How are you feeling? | |||

| Are you concerned about… | Can I refer you to… | ||

| □ Yes | □ No | Emotional health concerns | Mental health care, support groups |

| □ Yes | □ No | Impact of cancer on your family or friends | Social work |

| □ Yes | □ No | Finances, housing, employment, bills, transportation | Social work |

| □ Yes | □ No | Religious or spiritual life | Chaplain |

| 2. Physical screening and referral | |||

| Are you concerned about… | Can I refer you to… | ||

| □ Yes | □ No | Fatigue, insomnia | Mental health clinic, physical therapy, exercise, pulmonary |

| □ Yes | □ No | Memory, mental clarity | Neurology, neuropsychology |

| □ Yes | □ No | Strength, balance, range of motion | Rehabilitation (physical therapy/occupational therapy) exercise |

| □ Yes | □ No | Sexual health | Urology, ob/gyn, primary care |

| □ Yes | □ No | Pain | Pain clinic, palliative care |

| □ Yes | □ No | Eating, swallowing, or weight | Nutrition, ostomy, speech, swallowing |

This list was developed by the VHA Cancer Survivor Special Interest Group.

In addition to psychosocial support provided within oncology services, PACTs are structured to address the psychosocial stressors that veterans experience throughout cancer care. PACT consists of teams of PCPs and nurse clinicians who provide continuity of care for a panel of patients.18 Availability of “warm hand-offs” to integrated mental health partners (eg, social workers, health psychologists, or advanced practice nurses [Table 3]) may improve treatment for psychosocial problems and psychiatric diagnoses that arise during cancer care.19 Finally, complementary and alternative therapies are increasingly available within integrated care settings and may offer resources outside of traditional health care resources that complement resiliency fostered through existing modalities. PCPs across settings will benefit from the availability of an evidence base describing brief but continuous interventions for veterans’ experiencing psychosocial distress during cancer care.

This study was limited in several ways. The sample was a relatively homogenous group demographically, which did not adequately represent younger veterans or those from more diverse racial or ethnic backgrounds. Although focus groups began with a general question, subsequent questions targeted specific stress and coping content. Also, the study included veterans within 3 years of treatment and may not represent the views of all veterans posttreatment. Despite these limitations, a variety of sometimes disparate reactions were expressed, revealing themes that appear in the larger cancer literature, as well as unique elements of the veteran experience. This variability underscores the importance of patient-centered care tailored to the concerns of the individual.

These findings reinforce the indelible importance of the patient-clinician relationship on the health outcomes of veterans and how much patients rely on PCPs for psychosocial aspects of care. As the patient transitions from cancer treatment into a chronic disease management phase, PCPs re-emerge as the center of the care team tasked with an ever-expanding role of providing medical and psychosocial care for “the whole patient.”20 This study reinforces that cancer survivorship is a process, with different themes and reactions relevant at different points. Interventions need to be tailored to where patients are in that process and what they tell us.

Fast Facts….

Psychosocial distress–such as depression, cancer-specific worry, and cancer-related PTSD–may occur after cancer treatment2

Screening for distress at the time of cancer diagnosis and throughout the trajectory of care is needed3

Co-existing combat-related PTSD may amplify distress6

Elicit patient preferences and provide education about: (1) surveillance testing; (2) rehabilitation options (eg, fatigue, incontinence, impotence, etc); and (3) healthy behaviors

Consider perceived stigma (eg, being treated differently because of a cancer history) to prevent miscommunications or misperceptions

Refer to mental health partners (eg, social workers, health psychologists, or advanced practice nurses) to treat psychosocial problems and psychiatric diagnoses

Acknowledgments

Sources of support

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the VA Boston Healthcare System and the Boston VA Research Institute, both in Boston, Massachusetts. Additional support was provided by the Houston VA Health Services Research & Development Center of Excellence (HFP90-020) at the Michael E. DeBakey VAMC in Houston, Texas, and the Tuscaloosa VA Research & Development Service in Tuscaloosa, Alabama.

Footnotes

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Quadrant HealthCom Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

References

- 1.Moye J, Schuster JL, Latini DM, Naik AD. The future of cancer survivorship care for veterans. Fed Prac. 2010;37(27):36–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E, editors. From cancer patient to cancer survivor: Lost in transition. [Accessed July 2, 2012];The National Academies Press. website http://www.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=11468&page=R1.

- 3.American College of Surgeons. Cancer program standards 2012: Ensuring patient-centered care. American College of Surgeons; [Accessed July 2, 2012]. website http://www.facs.org/cancer/coc/cocprogramstandards2012.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oeffinger KC, McCabe MS. Models for delivering survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(32):5117–5124. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.0474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moye J, Gosian J, Snow R, Naik A. Vetcares Research Team. Emotional health following diagnosis and treatment of oral-digestive cancer in military veterans. Poster presentation at: 119th Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association; August 2011; Washington DC. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moye J, Archambault E, Schuster J, et al. The impact of military experience on adaptation to cancer among military veterans. Presentation at: 5th Biennial Cancer Survivorship Research Conference: Recovery and Beyond; June 17–19, 2010; Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sada YH, Street RL, Jr, Singh H, Shada RE, Naik AD. Primary care and communication in shared cancer care: A qualitative study. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(4):259–265. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burg MA, Grant K, Hatch R. Caring for patients with cancer histories in community-based primary care settings: A survey of primary care physicians in the southeastern U.S. Primary Health Care Research and Development. 2005;6(3):244–250. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Craike MJ, Livingston PM, Warne C. Sensitivity and specificity of the Distress Impact Thermometer for the detection of psychological distress among CRC survivors. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2011;29(3):231–241. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2011.563347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Recklitis CJ, Licht I, Ford J, Oeffinger K, Diller L. Screening adult survivors of childhood cancer with the distress thermometer: A comparison with the SCL-90-R. Psychooncology. 2007;16(11):1046–1049. doi: 10.1002/pon.1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Merport A, Bober S, Grose A, Recklitis C. Can the distress thermometer (DT) identify significant psychological distress in long-term cancer survivors? A comparison with the Brief Symptom Inventory-18 (BSI-18) Support Care Cancer. 2012;20(1):195–198. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1269-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morgan DL. Focus Groups as Qualitative Research. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krueger RA. Moderating Focus Groups. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: Developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(4):1758–1772. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deimling GT, Wagner LJ, Bowman KF, Sterns S, Kercher K, Kahana B. Coping among older-adult, long-term cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2006;15(2):143–159. doi: 10.1002/pon.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thewes B, Butow P, Girgis A, Pendlebury S. The psychosocial needs of breast cancer survivors; a qualitative study of the shared and unique needs of younger versus older survivors. Psychooncology. 2004;13(3):177–189. doi: 10.1002/pon.710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cancer Care Collaborative Special Interest Group on Cancer Survivorship. [Accessed March 10, 2012];Cancer Survivorship Tool-kit. United States Department of Veterans Affairs Intranet website. https://vaww.visn11.portal.va.gov/sites/VERC/vacase/collabs/survivor_toolkit/SitePages/Home.aspx.

- 18.Zivin K, Pfeiffer PN, Szymanski BR, et al. Initiation of primary care-mental health integration programs in the VA health system: Associations with psychiatric diagnoses in primary care. Med Care. 2010;48(9):843–851. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e5792b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patient Centered Primary Care Implementation Work Group. United States Department of Veterans Affairs; [Accessed March 15, 2012]. Patient centered medical home model concept paper. website http://www.va.gov/PrimaryCare/docs/pcmh_ConceptPaper.doc. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adler NE, Page AEK, editors. Cancer care for the whole patient: Meeting psychosocial health needs. The National Academies Press website; [Accessed March 15, 2012]. http://books.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=11993&page=1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]