Abstract

Capsinoids are non-pungent compounds with molecular structures similar to capsaicin, which has accepted thermogenic properties. To assess the acute effect of a plant-derived preparation of capsinoids on energy metabolism, we determined resting metabolic rate and non-protein respiratory quotient after ingestion of different doses of the capsinoids. Thirteen healthy subjects received four doses of the capsinoids (1, 3, 6 and 12 mg) and placebo using a crossover, randomized, double-blind trial. After a 10-h overnight fast as inpatients, resting metabolic rate was measured by indirect calorimetry for 45 min before and 120 min after ingesting capsinoids or placebo. Blood pressure and axillary temperature were measured before (-55 and -5 min) and after (60 and 120 min) dosing. Prior to dosing, mean resting metabolic rate was 6247 ± 92 kJ/d and non-protein respiratory quotient 0.86 ± 0.01. At 120 minutes after dosing, metabolic rate and non-protein respiratory quotient remained similar across the 4 capsinoids and placebo doses. Capsinoids also had no influence on blood pressure or axillary temperature. Capsinoids provided in four doses did not affect metabolic rate and fuel partitioning in humans when measured two hours after exposure. Longer exposure and higher capsinoids doses may be required to cause meaningful acute effects on energy metabolism.

Keywords: Capsinoids, thermogenesis, respiratory quotient, fat oxidation

Introduction

Obesity is pandemic and continues to increase in developed, developing and even some societal strata in emerging economies(1). At present, energy restriction and increased physical activity are advocated in most weight control programs; however sustained changes in diet and physical activity are difficult to achieve.

Growing interest exists to find natural substances or extracts that modify energy balance. Capsaicinoids (i.e., capsaicin) are naturally present in chili pepper. Capsaicin increases the activity of the sympathetic nervous system(2), in parallel with increased cathecolamine secretion(3-5), energy expenditure(4, 6) and fat oxidation(4, 7, 8). However, given its strong pungency, not all people feel comfortable consuming it. Capsaicin-like compounds such as capsinoids (i.e., capsiate, dihydrocapsiate and nordihydrocapsiate) are much less pungent(9, 10) and have also been shown to increase the activity of the sympathetic nervous system(11), adipose tissue UCP protein content(12), energy expenditure and fat oxidation(12) in mice. In humans, Ohnuki et al.(13) found increased body temperature and higher oxygen consumption after ingestion of a single dose of capsinoids-rich peppers (CH-19 sweet; Capsicum annuum L.). Additionally, an increased oxygen consumption (per kg of body weight) associated with a small reduction in body weight was observed in overweight individuals after ingesting 10 mg/d of encapsulated capsinoids for 4 weeks(14). Very recently, Snitker et al.(15) reported that overweight individuals ingesting 6 mg/day of encapsulated capsinoids for 12 weeks had increased fat oxidation and reduced abdominal fat compared with placebo treated subjects. Unfortunately, in these studies, energy expenditure was not normalized for the metabolically active mass, making the comparison within and between groups difficult with changes in body weight and body composition. Therefore, we investigated the acute effect of encapsulated capsinoids on metabolic rate and substrate oxidation in a crossover study.

We conducted a double-blind, placebo, controlled, single center, randomized, crossover clinical trial to test the impact of different doses of encapsulated, plant-derived capsinoids (1, 3, 6 and 12 mg) on resting metabolic rate and fat oxidation measured by indirect calorimetry. The primary objective of this randomized trial was to test the hypothesis that consumption of capsinoids increases resting energy expenditure and/or fat oxidation in humans. The secondary objective was to evaluate the effect of capsinoids on blood pressure and adverse events.

Methods

Subjects

Thirteen young (28.4 ± 1.4 y), non-smoking men were recruited by advertising in local newspaper, television and the Pennington Biomedical Research Center website. They were healthy as indicated by physical examination and routine medical laboratory tests and their body weight was stable over the past month. Participants had an average body mass index (BMI) of 27.1 ± 1.0 kg/m2 ranging from 22.3 – 34.8, body weight of 83.9 ± 4.7 kg (range: 60.5 – 117.5) and body fat content of 22.4 ± 1.6 % (range: 11.9 – 31.3). None of them exercised more than twice a week for the past 6 months and none participated in regular resistance exercise. Exclusion criteria also included attempt to diet to increase or decrease body weight, allergy to chili pepper, consuming more than 2 cups of tea or coffee/day or more than 3 standard alcohol drinks/day, use of weight loss drugs, drugs affecting energy metabolism and drugs for depression. The protocol was approved by the Pennington Biomedical Research Center Institutional Review Board and all subjects provided written informed consent.

Experimental design

This study was a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized, crossover clinical trial. After completing the screening process, participants presented at 6 pm at the Pennington In-Patient Unit for 5 days. At 6.30 pm they received a standardized dinner and, at 8 pm, a snack. This provided 50% of the basal energy requirement, calculated according to published equations(16). The macronutrient composition of the diet was 50% from carbohydrates, 30% from fat and 20% from protein. At 9 pm subjects were interviewed for the occurrence of symptoms within the last 12 hours(17). On the next day, in order to minimize physical activity, subjects remained in their bed for the entire duration of the resting metabolic rate (RMR) assessment. RMR was measured for 45 min (baseline) before ingestion of 12 gel capsules followed by another 120-min of RMR measurement. Doses (placebo, or capsinoids at 1, 3, 6 or 12 mg) were randomly assigned using a randomized number sequence. Urine was collected before and after the 165-min RMR measurement for nitrogen excretion rate. Blood pressure and body temperature were measured at -50, -5, 60, and 120 min of capsules ingestion. At the end of the 165-min RMR measurement, occurrence of symptoms for the last 3 hours was assessed according to a symptoms’ checklist(17). Total body fat content was measured by dual energy X-ray absorptiometry scan on one of the mornings after RMR testing. Finally, 72 h after the last testing day, subjects were contacted by phone and interviewed for the presence of symptoms and adverse events. Physical activity and consumption of tea, coffee and alcohol were not permitted during the week of metabolic evaluation.

Capsinoids capsules

Capsules contained an extract from pepper fruit variety CH-19 Sweet (Capsicum annuum L.). Capsinoids oil was extracted as follows: dried fruit was treated with hexane, and fruit sediment was removed by filtration, followed by evaporation and distillation with medium-chain triglycerides and column chromatography to yield purified capsinoids. Capsinoids consisted of capsiate, dihydrocapsiate and norhydrocapsiate in a 70:23:7 ratio (HPLC). The purified capsinoids were dissolved in rapeseed oil and encapsulated in vegetarian softgel capsules made of modified cornstarch, vegetable glycerin, and carageenan; each capsule contained 1 mg capsinoids and 199 mg of a mixture of rapeseed oil and medium-chain triglycerides. All capsules were manufactured in one batch. Stability tests determined that the product would be stable beyond the duration of the trial. The same amount of capsules (12) was given every testing day but with different proportions of capsules containing placebo or capsinoids. For example, with the 6-mg capsinoids dose, 6 capsules contained placebo and 6 capsules contained capsinoids. Capsules were ingested with 150 ml of tap water in less than two minutes, and they are expected to be absorbed within 10 minutes.

Indirect calorimetry and fuel oxidation

Resting metabolic rate was measured in fasting conditions with subject in supine position, awake, in a quiet environment (soft music was permitted) and with a room temperature of 22°C. Resting metabolic rate was determined from gas exchange measurements using a Deltatrac II metabolic cart (Deltatrac II, Datex-Ohmeda, Helsinki, Finland). The analyzer was calibrated before each study with standardized gases containing 5% CO2 and 95% O2. A transparent plastic hood connected to the device was placed over the head of the participant. VO2 and VCO2 were calculated from continuous measurements of CO2 and O2 concentrations in inspired and expired air diluted in a constant air flow of ~40 L/min. Oxygen consumption, CO2 production and energy expenditure standardized for temperature, pressure, and moisture were calculated at one minute intervals. Energy substrate oxidation was calculated using Jequier et al. equations taking into account urinary nitrogen excretion(18). The RMR response to the drug was evaluated as the net incremental area under the curve(19).

Body composition

Body fat mass and fat-free mass were measured on a Hologic Dual Energy X-ray Absorptiometer in the fan beam mode (QDR 4500; Hologic, Waltham, MA).

Blood Pressure and Body Temperature

Blood pressure was measured at -50, -5, 0, 60, and 120 min of capsule ingestion using a manometer (Baumanometer. W.A. Baum Co., Inc. USA). Axillary body temperature was measured using an electronic thermometer (Sure Temp 679, Welch Allyn).

Symptoms and Adverse Events

Assessment of the incidence of symptoms and adverse events, which might possibly be induced by capsinoids was done using a validated symptom questionnaire(17). This questionnaire assesses 34 different symptoms (e.g. energetic, tired, hungry, fresh, alert, sleepy, etc.) in 4 different intensities: not at all, slight amount, moderate amount or great amount. The questionnaire was applied the night before the metabolic testing, immediately after the 165-min metabolic testing and 72 h after the last metabolic testing.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SE. All statistical analyses were done with SAS software version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Data were analyzed using a two-way repeated measures ANOVA (SAS PROC MIXED) with dose and time as the fixed effects and subject as the random effect. The statistical significance for multiple comparisons was adjusted with respect to the Tukey-Kramer method to control for Type I error rate. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by the Pennington Biomedical Research Center Institutional Review Board (#27034). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Results

All subjects completed the 5-day metabolic rate assessment. No significant changes in body weight were detected during this period (0.15 ± 0.18 kg; range: -1.1 – 1.3; p=0.41). Capsinoids capsules were well tolerated and adverse events were similar across treatments (p>0.08). Likewise, systolic and diastolic blood pressures were unchanged over time and unaffected by capsinoids. A small but statistically significant increase in body temperature was observed when body temperature was compared at -50 min and 120 min after ingestion of the capsules (35.9 ± 0.1 to 36.0 ± 0.0°C; p=0.02) but was not affected by treatment (p=0.16).

Energy metabolism

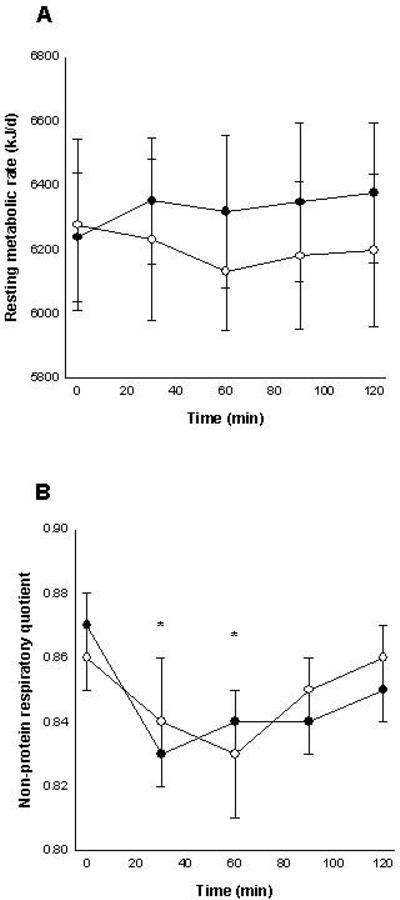

Resting metabolic rate before dosing had an intraindividual coefficient of variation (CVi) of 4.1% (SD = 259 kJ/d). After capsinoids ingestion, no differences in metabolic rate were noted as a function of time (p=1.00), capsinoids dose (p=0.91) or its interaction (p=1.00) (Figure 1A). The RMR incremental area under the curve (kJ × min/day) was also similar between doses (p=0.48; Table 1). In addition, the change in metabolic rate in response to dosing did not show differences when compared with placebo (p>0.53; Table 1).

Figure 1.

Resting metabolic rate (A) and non-protein respiratory quotient (B) before and for 120 min after 12 mg capsinoids (open circle) or placebo (closed circle) ingestion. Data for lower doses (1, 3 and 6 mg) of capsinoids are not shown. *p<0.05.

Table 1.

Resting metabolic rate area under the curve and change from baseline to post-capsinoids ingestion.

| Placebo | 1 mg | 3 mg | 6 mg | 12 mg | Capsinoids effect (p value) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMR before pills ingestion (kJ/d) | 6238 ± 201 | 6305 ± 230 | 6180 ± 163 | 6247 ± 205 | 6276 ± 268 | 0.99 |

| RMR iAUC (kJ × min/day) | 11163 ± 8004 | −8435 ± 11485 | 8435 ± 9335 | −4134 ± 8017 | −9858 ± 13636 | 0.48 |

| Δ RMRmean (kJ/d) | 109 ± 84 | −79 ± 113 | 63 ± 92 | −46 ± 79 | −92 ± 134 | 0.53 |

| Δ RMRpeak (kJ/d) | 322 ± 92 | 142 ± 117 | 293 ± 109 | 205 ± 92 | 155 ± 117 | 0.66 |

Mean ± SE. The mixed model with repeated measures was used with dose as the fixed effect and subject as the random effect.

RMR iAUC: RMR incremental area under the curve for 120 min after capsinoids or placebo ingestion.

Δ RMRmean: Mean RMR after capsinoids ingestion – baseline RMR.

Δ RMRpeak: Maximal RMR after capsinoids ingestion – baseline RMR.

The intraindividual variability in non-protein respiratory quotient (NPRQ) before dosing was 3.1 % (SD = 0.03). Non-protein respiratory quotient was not affected by treatment (p=0.36) or treatment × time interaction (p=1.00). However, a significant time effect was noted (p=0.002; Figure 1B) with a decrease in NPRQ 30 and 60 min after dosing. After that time, NPRQ values were similar to those observed during the baseline period (p>0.19; Figure 1B).

Fat oxidation before capsules ingestion had a CVi of 45% (SD = 18 g/d). No significant effect of capsinoids dose was observed on fat oxidation (p=0.24). However, fat oxidation was increased 30 min (p=0.0002) and 60 min (p=0.007) after dosing, when compared with baseline fat oxidation (baseline, 30 and 60 min: 40 ± 3, 62 ± 4 and 57 ± 3 g/d, respectively). Mirror-image results were observed for carbohydrate oxidation, which was reduced 30 min after dosing, when compared with baseline values (118 ± 9 vs. 156 ± 8 g/d, respectively; p=0.01).

We also evaluated the influence of the chronological order (Day 1, 2, etc.) on energy metabolism, and no differences were detected among days on baseline RMR (Day 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 in kJ/d: 6166±166, 6247±211, 6190±222, 6260±199 and 6379±262, respectively; p=0.96) or NPRQ (Day 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5: 0.85±0.01, 0.87±0.01, 0.86±0.01, 0.87±0.01 and 0.86±0.02, respectively; p=0.59). Similar results were found when the 2-h post-pill RMR and NPRQ were assessed.

Discussion

Using a crossover design, we failed to demonstrate a significant effect of capsinoids on metabolic rate and fuel partitioning in humans. With our design we did not have to normalize energy expenditure data for body composition, since each subject was his own control with probably no change in body composition over the 5 days of testing. In addition to these results, blood pressure and axillary temperature were not affected by capsinoids.

One potential target for obesity treatment and/or prevention is metabolic rate. It is proposed that even a small decrease in energy intake (<200 kJ/d) may be able to prevent weight gain(20), although this concept has been vigorously challenged(21-23). Similarly, one can make the case that a small but consistent increase in energy expenditure will help individuals to maintain body weight or even lose weight. The best option to increase energy expenditure is by increasing physical activity; however, the current obesogenic environment makes this option often difficult or impossible for most people(24). Alternatively, ingestion of compounds with thermogenic properties in combination with energy restriction might eventually lead to higher body weight loss.

Capsinoids share a similar molecular structure with capsaicin. These compounds may therefore have a capsaicin-like effect on metabolic rate in humans since animal studies support such a thermogenic effect(11, 12). In humans, Inoue et al.(14) assessed the effect of 3 and 10 mg/d of encapsulated capsinoids for 4 weeks on metabolic rate and respiratory quotient. No changes in these variables were observed. However, when only overweight individuals were included in the analysis, a larger increase in oxygen consumption with the highest capsinoids dose vs. placebo was detected. A similar but not significant increase in metabolic rate and fat oxidation were observed (p<0.10), but without changes in respiratory quotient. Unfortunately, the lack of normalization of metabolic rate for the metabolically active body mass did not allow firm conclusions. In a recent study in overweight men, encapsulated capsinoids (6 mg/d for 12 weeks) did not modify metabolic rate, although a higher but not significant increase in fat oxidation was detected after the 12-week treatment period when compared to the placebo group. However, the authors failed to normalize their data for the metabolically active tissue before and after intervention(15).

Several factors may explain our results, including the low doses and short exposure to capsinoids, a lack of power to find significant differences or simply the absence of thermogenic effect of capsinoids. Our study was designed with the power to detect a 5% effect in RMR or approximately 300 kJ/d. After two hours of metabolic rate measurement, the differences in RMR after capsinoids ingestion compared with placebo were well below our detection limit and more importantly of no physiological importance on body weight. Therefore, we are confident that the lack of significant difference is not due to a type II error.

Another possibility is that the measurement of energy expenditure was not of sufficient duration (only 120 minutes after dosing) to detect an effect. Such an observation has been made with sibutramine, a medication that is approved for obesity and which has a small effect on energy expenditure. Seagle et al.(25) did not find an effect of sibutramine (10 mg or 30 mg/d) in obese women when they measured resting metabolic rate for only 3 hours. However, Hansen et al.(26) measured energy expenditure for 5.5 hours after dosing with 30 mg sibutramine compared to placebo in fed and fasted men. There was a sibutramine-induced increase in energy expenditure of about 3-5%. Data from mice also supports the idea that longer exposure to high doses of capsinoids may be required to increase metabolic rate, since the thermogenic effect may be mediated by up-regulation of uncoupling proteins(12).

Alternatively, capsinoids might influence food intake by suppressing hunger and increasing satiety in humans(27-29). We did not specifically assess food intake in the present study, although the symptoms questionnaire given to the volunteers included a question about hunger feelings. We found no difference in hunger across treatments.

In conclusion, a combination of longer exposure time and higher capsinoids dose may be required to increase metabolic rate in a physiologically meaningful way. Therefore, there is still a need to investigate the potential long-term effects of capsinoids on metabolic rate in humans. In conclusion, our study does not support the hypothesis that capsinoids can be helpful in increasing energy expenditure and fat oxidation in humans, at least over two hours after exposure. Long term use of capsinoids needs to be further tested to establish them as a potential weight control agent.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Ajinomoto Co., Inc (Tokyo, Japan). J.E.G. was supported by a fellowship from The International Nutrition Foundation/Ellison Medical Foundation. Ajinomoto Co., Inc. did not have influence in the subjects’ recruitment, data collection, analysis, interpretation and in the decision to publish this study. E.R, study design, data analysis and preparation of the manuscript. D.R, study design and preparation of the manuscript. J.G, data collection, analysis and preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None of the authors have any conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Nishida C, Uauy R, Kumanyika S, Shetty P. The joint WHO/FAO expert consultation on diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases: process, product and policy implications. Public Health Nutr. 2004 Feb;7(1A):245–50. doi: 10.1079/phn2003592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watanabe T, Kawada T, Kurosawa M, Sato A, Iwai K. Adrenal sympathetic efferent nerve and catecholamine secretion excitation caused by capsaicin in rats. Am J Physiol. 1988 Jul;255(1 Pt 1):E23–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1988.255.1.E23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kawada T, Sakabe S, Watanabe T, Yamamoto M, Iwai K. Some pungent principles of spices cause the adrenal medulla to secrete catecholamine in anesthetized rats. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1988 Jun;188(2):229–33. doi: 10.3181/00379727-188-2-rc1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kawada T, Watanabe T, Takaishi T, Tanaka T, Iwai K. Capsaicin-induced beta-adrenergic action on energy metabolism in rats: influence of capsaicin on oxygen consumption, the respiratory quotient, and substrate utilization. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1986 Nov;183(2):250–6. doi: 10.3181/00379727-183-42414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watanabe T, Kawada T, Yamamoto M, Iwai K. Capsaicin, a pungent principle of hot red pepper, evokes catecholamine secretion from the adrenal medulla of anesthetized rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1987 Jan 15;142(1):259–64. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(87)90479-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoshioka M, Lim K, Kikuzato S, Kiyonaga A, Tanaka H, Shindo M, et al. Effects of red- pepper diet on the energy metabolism in men. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 1995 Dec;41(6):647–56. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.41.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoshioka M, St-Pierre S, Suzuki M, Tremblay A. Effects of red pepper added to high-fat and high-carbohydrate meals on energy metabolism and substrate utilization in Japanese women. Br J Nutr. 1998 Dec;80(6):503–10. doi: 10.1017/s0007114598001597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lejeune MP, Kovacs EM, Westerterp-Plantenga MS. Effect of capsaicin on substrate oxidation and weight maintenance after modest body-weight loss in human subjects. Br J Nutr. 2003 Sep;90(3):651–59. doi: 10.1079/bjn2003938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kobata K, Sutoh K, Todo T, Yazawa S, Iwai K, Watanabe T. Nordihydrocapsiate, a new capsinoid from the fruits of a nonpungent pepper, capsicum annuum. J Nat Prod. 1999 Feb;62(2):335–6. doi: 10.1021/np9803373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iida T, Moriyama T, Kobata K, Morita A, Murayama N, Hashizume S, et al. TRPV1 activation and induction of nociceptive response by a non-pungent capsaicin-like compound, capsiate. Neuropharmacology. 2003 Jun;44(7):958–67. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(03)00100-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ohnuki K, Haramizu S, Oki K, Watanabe T, Yazawa S, Fushiki T. Administration of capsiate, a non-pungent capsaicin analog, promotes energy metabolism and suppresses body fat accumulation in mice. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2001 Dec;65(12):2735–40. doi: 10.1271/bbb.65.2735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Masuda Y, Haramizu S, Oki K, Ohnuki K, Watanabe T, Yazawa S, et al. Upregulation of uncoupling proteins by oral administration of capsiate, a nonpungent capsaicin analog. J Appl Physiol. 2003 Dec;95(6):2408–15. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00828.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohnuki K, Niwa S, Maeda S, Inoue N, Yazawa S, Fushiki T. CH-19 sweet, a non-pungent cultivar of red pepper, increased body temperature and oxygen consumption in humans. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2001 Sep;65(9):2033–6. doi: 10.1271/bbb.65.2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inoue N, Matsunaga Y, Satoh H, Takahashi M. Enhanced energy expenditure and fat oxidation in humans with high BMI scores by the ingestion of novel and non-pungent capsaicin analogues (capsinoids). Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2007 Feb;71(2):380–9. doi: 10.1271/bbb.60341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Snitker S, Fujishima Y, Shen H, Ott S, Pi-Sunyer X, Furuhata Y, et al. Effects of novel capsinoid treatment on fatness and energy metabolism in humans: possible pharmacogenetic implications. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009 Jan;89(1):45–50. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Human energy requirements. Scientific background papers from the Joint FAO/WHO/UNU Expert Consultation. October 17-24, 2001. Rome, Italy. Public Health Nutr. 2005 Oct;8(7A):929–1228. doi: 10.1079/phn2005778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wadden TA, Stunkard AJ, Day SC, Gould RA, Rubin CJ. Less food, less hunger: reports of 11 appetite and symptoms in a controlled study of a protein-sparing modified fast. Int J Obes. 1987;11(3):239–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jequier E, Acheson K, Schutz Y. Assessment of energy expenditure and fuel utilization in man. Annu Rev Nutr. 1987;7:187–208. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.07.070187.001155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gannon MC, Nuttall FQ, Westphal SA, Neil BJ, Seaquist ER. Effects of dose of ingested glucose on plasma metabolite and hormone responses in type II diabetic subjects. Diabetes Care. 1989 Sep;12(8):544–52. doi: 10.2337/diacare.12.8.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hill JO. Understanding and addressing the epidemic of obesity: an energy balance perspective. Endocr Rev. 2006 Dec;27(7):750–61. doi: 10.1210/er.2006-0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Butte NF, Ellis KJ. Comment on “Obesity and the environment: where do we go from here?”. Science. 2003 Aug 1;301(5633):598. doi: 10.1126/science.1085985. author reply. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Swinburn BA, Jolley D, Kremer PJ, Salbe AD, Ravussin E. Estimating the effects of energy imbalance on changes in body weight in children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006 Apr;83(4):859–63. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.4.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weinsier RL, Bracco D, Schutz Y. Predicted effects of small decreases in energy expenditure on weight gain in adult women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1993 Dec;17(12):693–700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ravussin E. Obesity in Britain. Rising trend may be due to “pathoenvironment”. BMJ. 1995 Dec 9;311(7019):1569. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7019.1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seagle HM, Bessesen DH, Hill JO. Effects of sibutramine on resting metabolic rate and weight loss in overweight women. Obes Res. 1998 Mar;6(2):115–21. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1998.tb00324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hansen DL, Toubro S, Stock MJ, Macdonald IA, Astrup A. Thermogenic effects of sibutramine in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998 Dec;68(6):1180–6. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/68.6.1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoshioka M, Doucet E, Drapeau V, Dionne I, Tremblay A. Combined effects of red pepper and caffeine consumption on 24 h energy balance in subjects given free access to foods. Br J Nutr. 2001 Feb;85(2):203–11. doi: 10.1079/bjn2000224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoshioka M, St-Pierre S, Drapeau V, Dionne I, Doucet E, Suzuki M, et al. Effects of red pepper on appetite and energy intake. Br J Nutr. 1999 Aug;82(2):115–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reinbach HC, Smeets A, Martinussen T, Moller P, Westerterp-Plantenga MS. Effects of capsaicin, green tea and CH-19 sweet pepper on appetite and energy intake in humans in negative and positive energy balance. Clin Nutr. 2009 Jun;28(3):260–5. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]