Abstract

Background

Patients experience reductions in quality of life (QOL) while receiving cancer treatment and several approaches have been proposed to address QOL issues. In this project the QOL differences between older adult (age 65+) and younger adult (age 18-64) advanced cancer patients in response to a multidisciplinary intervention designed to improve QOL were examined.

Methods

This study was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT01360814. Newly diagnosed advanced cancer patients undergoing radiation therapy were randomized to active QOL intervention or control groups. Those in the intervention group received six multidisciplinary 90-minute sessions designed to address the five major domains of QOL. Outcomes measured at baseline and weeks 4, 27 and 52 included QOL (Linear Analogue Self Assessment [LASA], Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy - General [FACT-G]) and mood (Profile of Mood States [POMS]). Kruskall-Wallis methodology was used to compare scores between older and younger adult patients randomized to the intervention.

Results

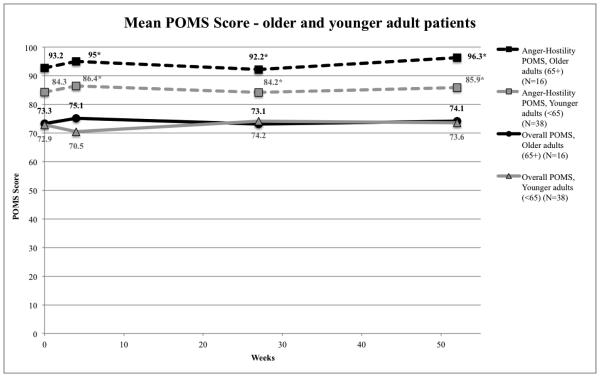

Of 131 patients in the larger randomized controlled study, we report data on 54 evaluable patients (16 older adults and 38 younger adults) randomized to the intervention. Older adult patients reported better overall QOL (LASA 74.4 vs 62.9, p=0.040), higher social well-being (FACT-G 91.1 vs 83.3, p=0.045), and fewer problems with anger (POMS Anger-Hostility 95.0 vs 86.4, p=0.028). Long-term benefits for older patients were seen in the Anger-Hostility scale at week 27 (92.2 vs 84.2, p=0.027) and week 52 (96.3 vs 85.9, p=0.005).

Conclusions

Older adult patients who received a multidisciplinary intervention to improve QOL while undergoing advanced cancer treatments benefitted differently in some QOL domains, compared to younger adult patients. Future studies can provide further insight on how to tailor QOL interventions for these age groups.

Keywords: well-being, mood, elderly, psycho-oncology, psychosocial, multidisciplinary intervention

INTRODUCTION

In the United States, cancer is the second-leading cause of death in the older (65+) population and is soon predicted to surpass heart disease as the leading cause of death (Berger et al., 2006; Murphy et al., 2012; Muss, 2009). Cancer disproportionately affects the elderly. In 2009, 53.2% of new cancer diagnoses and 69.2% of cancer deaths occurred in the older U.S. population, with the median age at diagnosis being 66 years old (Howlader et al., 2012). The diagnosis and treatment of cancer can have a negative impact on older individuals’ quality of life (QOL), affecting multiple domains of QOL (Puts et al., 2011; Reeve et al., 2009). As the U.S. geriatric population is expected to grow by 42% between 2010 and 2050, addressing the negative impacts of cancer on older patients’ QOL will become an increasingly important public health issue (Vincent and Velkoff, 2010).

The scientific literature contains relatively few studies examining the differences in QOL between geriatric and non-geriatric cancer patients. Older adult patients with cancer have been shown to score worse than younger patients in certain QOL domains, especially those relating to physical functioning (Akechi et al., 2012; Koo et al., 2012). These differences may be related to higher comorbidity with increased age (Ambs et al., 2008).

Other factors that negatively influence QOL in older adults with cancer include decreased ability to perform activities of daily living (ADLs), chronic pain, and symptoms such as fatigue, nausea and vomiting (Akechi et al., 2012; Koo et al., 2012). Although interventions to improve QOL have been conducted, most studies assess the effects of these interventions after cancer treatment has been completed (see Raingruber (2011) for literature review and references to other studies). Interventions to improve QOL include individual cognitive behavioral therapy and counseling, group sessions, and telephone interviews (Raingruber, 2011). The few published studies on interventions that address QOL of older adult cancer patients during cancer treatment show that targeted QOL interventions in older adult cancer patients can positively impact their QOL (Lapid et al., 2007; Mantovani et al., 1996; Rummans et al., 2006).

Previous studies have used QOL measures to assess the outcomes of isolated psychosocial, physical and other interventions (Raingruber, 2011). However, the literature contains few studies that have combined these elements in a multidisciplinary approach (Lapid et al., 2007; Rummans et al., 2006). Similarly, although telephone follow-up has been shown to positively impact cancer patients, few studies have investigated the QOL effects of these interventions for older adults (Rose et al., 2008).

Our research group previously conducted a randomized, controlled clinical trial to compare the efficacy of a multidisciplinary QOL intervention with standard care for advanced cancer patients (Clark et al., 2013). Results of this trial showed patients receiving the intervention had increased QOL as measured by the FACT-G (Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – General) immediately following the 4-week intervention. From a clinical standpoint, in some instances clinicians might assume that older patients with advanced cancer have worse QOL, and reason that older patients may not respond to interventions to improve QOL as well as younger patients. In this secondary analysis, our group sought to assess whether or not age influenced patient responses to the QOL intervention. We hypothesize that there will be no difference in patient response to the QOL intervention between older and younger adult patients with advanced cancer.

METHODS

Data for this study were from a randomized, controlled clinical trial which compared the efficacy of a six session multidisciplinary structured QOL group intervention with telephone follow-up to standard care for advanced cancer patients undergoing radiation therapy (Clark et al., 2013). Randomization was conducted via a computer-based Pocock-Simon (Pocock and Simon, 1975) dynamic allocation procedure to balance the arms across the stratification factors of type of primary malignant tumor, ECOG performance status, age, and planned cancer treatment. The clinical trial was approved by the Institutional Review Board, registered as NCT01360814 on ClinicalTrials.gov, and conducted at the Mayo Clinic Cancer Center.

The intervention was designed to enhance five QOL domains, including cognitive, physical, emotional, spiritual, and social functioning. The intervention period lasted 2-4 weeks and consisted of six 90-minute group sessions as described in detail elsewhere (Clark et al., 2013). The intervention was conducted during active radiotherapy treatment. Each session was led by a multidisciplinary team using standardized physical therapy, education, cognitive-behavioral interventions, discussion and support, spiritual reflection, and relaxation training. Following radiation treatment, participants received ten brief structured telephone follow-up counseling sessions.

Patient Population

Patients were at least 18 years of age who in the previous 12 months had been diagnosed with advanced cancer (including brain, gastrointestinal, head and neck, lung, and others). Patients had an estimated five-year survival rate of 0%-50% as determined clinically by their primary radiation oncologist and were scheduled to receive at least one week of radiation therapy. Participants received random assignments to either intervention or standard care control groups. To assure lack of severe depression, suicidal ideation or cognitive impairment, screening using the Beck Depression Inventory II and the Mini-Mental State Examination was conducted at baseline.

Outcome Measures

Study patients completed questionnaires at baseline and weeks 4, 27, and 52 to assess QOL and mood. The questionnaires used were the Linear Analogue Self Assessment Scale (LASA), FACT-G version 4 (the primary outcome measure), and the Profile of Mood States (POMS). Data on the reliability of the instruments can be found in the references cited in the instrument descriptions.

The LASA consists of 12 items and is a self-report of general measures of QOL that was constructed at Mayo Clinic for use in cancer patients (Bretscher et al., 1999). A single item assesses overall QOL: “During the past week, including today, how would you describe your overall quality of life?” An 11-point Likert scale, ranging from 0=“As bad as it can be” to 10=“As good as it can be,” is used to assess the overall QOL and 11 dimensions: Mental well-being (WB), Physical WB, Emotional WB, Social Activity, Spiritual WB, Pain Frequency, Pain Severity, Fatigue, Social Support, Financial concerns, and Legal concerns. Other studies have validated LASA items as measures of global and dimensional QOL constructs in numerous settings (Locke et al., 2007).

The FACT-G is a self-report of QOL for patients with cancer of any tumor type (Cella et al., 1993). Each of the 28 items is scored from 0=“Not at all” to 4=“Very much.” Questions address four subscales: Functional, Physical, Social, and Emotional WB. The FACT-G has been used widely in clinical trials and has been well validated; it is simple to complete and has been shown to be sensitive in assessing performance status and extent of disease (Cella et al., 1993).

The POMS is a self-report of different mood states categorized into 6 scales (Anger-Hostility, Tension-Anxiety, Depression-Dejection, Vigor-Activity, Fatigue-Inertia, Confusion-Bewilderment) and a total mood disturbance score (McNair et al., 1971). Using this 30-item questionnaire, patients rate the frequency with which they experience various moods on a scale from 0-4 with 0=”Not at all” and 4=”Extremely.” The POMS has been found to be reliable and valid in assessing patients with cancer (Curran et al., 1995).

Statistical Analysis

Outcome measures were scored according to the assessment specific scoring algorithms. For comparability, all scores (total scores and subscale scores) were converted to a 0-100 point scale with 100 being best. Changes from baseline scores were calculated.

Due to limited sample size, the statistical analyses presented here are exploratory and hypothesis generating and focus on estimation without adjustment for multiple testing. Therefore, descriptive statistics such as mean (standard deviation) and frequency (percentage) are used to summarize patient demographics and QOL scores within age groups. Should there have been indication to do so, statistical tests on endpoints (two-sample t-test for continuous data; Wilcoxon rank-sum test, Fisher’s exact test, or Chi-square test for ordinal data) were used to determine differences between age groups at the α=0.05 significance level. Repeated measures ANOVA was performed to determine which relationships over time, if any, exist between the post-intervention QOL scores and patient baseline characteristics.

RESULTS

Of the 131 patients entering the parent study, 65 were randomized to the intervention arm. Of these, 54 were evaluable and included in the analysis. Evaluable patients completed at least 4 of 6 intervention sessions and completed both baseline and week 4 assessments as per study criteria. Older (N=16) and younger (N=38) patient characteristics are reported in Table 1. The two groups were significantly different in primary cancer site (p=0.01) and current employment (25% of older patients currently employed vs. 71.1% of younger patients, p<0.01). The patients in both age groups were predominantly male. Most were Caucasian, married, and had at least a high school diploma. The majority reported Protestant religious affiliation. There were no significant differences between groups in terms of performance score, current chemotherapy, previous radiation therapy, prior surgery and radiation site. Baseline QOL was compared for brain vs all other cancer sites and brain or head & neck vs all other cancer sites. There were no differences at baseline, thus, while the groups were imbalanced, there was no bias prior to treatment.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of geriatric (N=16) vs. non-geriatric (N=38) intervention groups

| Intervention Arm: Baseline Patient Characteristics | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 65+ Older adult (N=16) |

<65 Younger adult (N=38) |

p value | |

| Age | <0.01 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 71.0 (5.0) | 54.2 (8.6) | |

| Gender | 0.82 | ||

| Male | 10 (62.5%) | 25 (65.8%) | |

| Race | 0.26 | ||

| White | 15 (93.8%) | 37 (97.4%) | |

| Black or African American | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.6%) | |

| Asian | 1 (6.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Primary Cancer Site | 0.01 | ||

| Brain | 0 (0.0%) | 8 (21.1%) | |

| Head & Neck | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (18.4%) | |

| Lung | 5 (31.3%) | 5 (13.2%) | |

| GI | 10 (62.5%) | 11 (28.9%) | |

| Other | 1 (6.3%) | 7 (18.4%) | |

| Performance Score | 0.66 | ||

| Fully Active | 8 (50.0%) | 22 (57.9%) | |

| Restricted | 8 (50.0%) | 15 (39.5%) | |

| Ambulatory | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.6%) | |

| Receiving Current Chemotherapy | 0.59 | ||

| Yes | 14 (87.5%) | 31 (81.6%) | |

| Previous Radiation Therapy | 0.62 | ||

| Yes | 1 (6.3%) | 4 (10.5%) | |

| Prior Surgery | 0.89 | ||

| Yes | 15 (93.8%) | 36 (94.7%) | |

| Radiation Site | 0.10 | ||

| Brain | 0 (0.0%) | 8 (21.1%) | |

| Abdomen | 4 (25.0%) | 4 (10.5%) | |

| Pelvic | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (10.5%) | |

| Lung | 4 (25.0%) | 5 (13.2%) | |

| Other | 8 (50.0%) | 17 (44.7%) | |

| Education Level | 0.61 | ||

| Some high school | 1 (6.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| H.S. graduate/GED | 5 (31.3%) | 9 (23.7%) | |

| Some college or vocational | 5 (31.3%) | 11 (28.9%) | |

| Graduate w/ 4 yr degree | 2 (12.5%) | 10 (26.3%) | |

| Post graduate study | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.6%) | |

| Graduate or professional degree | 2 (12.5%) | 6 (15.8%) | |

| Other | 1 (6.3%) | 1 (2.6%) | |

| Current Employment | <0.01 | ||

| Yes | 4 (25.0%) | 27 (71.1%) | |

| Marital Status | 0.2488 | ||

| Married | 13 (81.3%) | 35 (92.1%) | |

| Single | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.6%) | |

| Widowed | 3 (18.8%) | 2 (5.3%) | |

| Religious Affiliation | 0.2485 | ||

| Catholic | 2 (12.5%) | 12 (31.6%) | |

| Protestant | 11 (68.8%) | 21 (55.3%) | |

| Jewish | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (5.3%) | |

| None | 2 (12.5%) | 3 (7.9%) | |

| Other | 1 (6.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

p<0.05 statistically significant

Table 2 depicts changes in patient reported scores at each measureable time point. At week 4, as measured by the LASA, older patients reported improved overall QOL (mean 2.5, CI (−7.3,12.3)), and improved Mental WB (mean 0.6, CI (−7,8.3)), Physical WB (mean 1.9, CI (−8.5,12.2)), Emotional WB (mean 0.6, CI (−7,8.3)) and Social Support (mean 3.1, CI (−3.5,9.8)) whereas younger patients reported decreased overall QOL (mean −4.7, CI (−11.7,2.2)) and lower scores in all LASA sub-domains. In particular, younger patients had a mean decrease of 10.5 points in the Fatigue scale which equates to worse fatigue. The trajectory of overall QOL scores over time by treatment group is displayed in Figure 1. The difference in overall QOL at week 4 was clinically significant (11.5 point difference) as well as statistically significant (p=0.04). No statistically significant differences between age groups occurred at week 27 or 52. However, some notable trends were observed. At week 27, older patients showed improvements in 7 of the 12 QOL areas and at week 52 they showed improvements in 10 of the 12 areas. Of note is a mean 10 (CI (−2.6,22.6)) point increase in Physical WB at week 27 and a mean 9.2 decrease implying worse fatigue at week 52. In comparison, at week 27 younger patients showed improvements in 7 of the 12 QOL areas; however at week 52 they showed improvements in 3 of the 12 areas. Of note is a mean 9.7 (CI (2.1,17.3)) point increase in Social Activity at week 27. At week 52, younger patients reported a mean 10 (CI (−1.3,21.3)) point improvement for less financial concerns and a mean 10 (CI (−22.5,2.5)) point decrease implying more legal concerns.

Table 2.

Mean change from baseline scores over time

| < 65 Younger adult | > 65 Older adult | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Weeks | 0 (N=38) |

4 (N=38) |

27 (N=35) |

52 (N=31) |

0 (N=16) |

4 (N=16) |

27 (N=16) |

52 (N=14) |

| LASA Overall QOL | 0.0 | −4.7 | 4.7 | −0.7 | 0.0 | 2.5 | 3.1 | 4.2 |

| LASA Mental WB | 0.0 | −2.6 | 3.8 | −5.9 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 4.4 | 4.2 |

| LASA Physical WB | 0.0 | −1.8 | 2.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.9 | 10.0 | 5.8 |

| LASA Emotional WB | 0.0 | −1.1 | 4.4 | −4.4 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 1.9 | 2.5 |

| LASA Social Activity | 0.0 | −0.8 | 9.7 | 1.5 | 0.0 | −3.8 | −1.3 | 5.8 |

| LASA Spiritual WB | 0.0 | −3.4 | 0.3 | −4.8 | 0.0 | −1.9 | 0.6 | 5.0 |

| LASA Pain Frequency | 0.0 | −3.2 | −2.5 | −7.4 | 0.0 | −3.1 | 2.5 | −3.3 |

| LASA Pain Severity | 0.0 | −2.9 | −0.9 | −1.1 | 0.0 | −3.8 | 2.5 | 0.8 |

| LASA Fatigue | 0.0 | −10.5 | −6.9 | −8.5 | 0.0 | −1.3 | −0.6 | −9.2 |

| LASA Social Support | 0.0 | −1.6 | −2.2 | −7.0 | 0.0 | 3.1 | −0.6 | 1.7 |

| LASA Financial | 0.0 | −3.4 | 6.9 | 10.0 | 0.0 | −4.4 | −6.9 | 6.7 |

| LASA Legal | 0.0 | −3.4 | −0.6 | −10.0 | 0.0 | −6.9 | −6.3 | 3.3 |

| FACT-G Total | 0.0 | −1.7 | 1.7 | −0.7 | 0.0 | −0.6 | −0.8 | −0.2 |

| FACT-G Physical WB | 0.0 | −5.8 | 2.8 | 1.6 | 0.0 | −5.5 | −1.7 | −3.8 |

| FACT-G Social WB | 0.0 | −1.1 | −2.3 | −4.8 | 0.0 | 1.7 | −1.9 | −2.3 |

| FACT-G Emotional WB | 0.0 | 1.2 | 2.1 | −0.2 | 0.0 | 0.5 | −3.1 | −1.7 |

| FACT-G Functional WB | 0.0 | −0.9 | 4.3 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 1.1 | 3.1 | 9.8 |

| POMS Total | 0.0 | −2.4 | 0.3 | −1.2 | 0.0 | 1.8 | −0.2 | 1.8 |

| POMS Tension-Anxiety | 0.0 | 2.2 | 4.1 | 1.5 | 0.0 | −0.9 | −1.3 | 3.8 |

| POMS Depression-Dejection | 0.0 | 0.8 | 1.6 | −1.3 | 0.0 | 0.3 | −2.8 | −0.4 |

| POMS Anger-Hostility | 0.0 | 2.1 | −0.3 | 1.3 | 0.0 | 2.2 | −0.6 | 5.0 |

| POMS Vigor-Activity | 0.0 | −9.3 | 2.8 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 4.7 | 3.1 | 1.7 |

| POMS Fatigue-Inertia | 0.0 | −9.2 | −5.3 | −4.8 | 0.0 | 0.3 | −0.3 | −0.4 |

| POMS Confusion-Bewilderment | 0.0 | −1.1 | −0.9 | −4.3 | 0.0 | 4.4 | 0.6 | 1.3 |

Figure 1.

QOL differences between older adult (N=16) and younger adult (N=38) intervention groups over time

The mean overall QOL LASA score measuring overall QOL was significantly higher for older adult patients than younger adult patients at week 4 of the intervention (74.4 vs 62.9, p=0.04).

*Week 4 overall LASA statistically significant

The FACT-G instrument scores did not show patterns or large changes from baseline (Figure 2). Actual scores at week 4 indicate older patients scored 7.8 points higher on the Social WB subscale and 7.3 points higher on the total FACT-G score. While the week 4 Social WB score is statistically significantly different (p=0.045), there was no difference in the improvement or decrease from baseline. FACT-G scores indicated that over time, older patients had decreases in Physical WB and increases in Functional WB; at week 52, older patients reported a 9.8 point (CI (−4.4,24)) improvement in Functional WB. Younger patients had decreases in Social WB over time, but not of any statiscally significant magnitude.

Figure 2.

Mean overall and Social well-being FACT-G score between older adult (N=16) and younger adult (N=38) intervention groups over time

The mean FACT-G total score for older adult and younger adult patients stayed relatively stable with no significant differences between these two groups throughout the intervention, but older adult patients had a significantly higher Social well-being score at week 4 of the intervention (91.1 vs 83.3, p=0.045).

*Week 4 FACT-G Social well-being score statistically significant

POMS total and subscale scores showed a pattern similar to the FACT-G scores; there were some indications that actual scores were different at various time points (Figure 3) but changes from baseline were minimal. There were no statistically significant differences in the POMS total score between older adult and younger adult patients at any point. However, older adult patients reported significantly better functioning in the Anger-Hostility scale than younger adult patients at all times after the intervention (week 4: 95 vs 86.4, p=0.028; week 27: 92.2 vs 84.2, p=0.027; week 52: 96.3 vs 85.9, p=0.005). Older patients’ Anger-Hostility scores were approximately 10 points better than those of younger patients, suggesting these results are also clinically meaningful. There were no statistically significant differences in the other POMS scales. Younger patients did report worse scores in Vigor-Activity (mean −9.3, CI (−16.7,−2)) and Fatigue-Inertia (mean −9.2, CI (−16.6,−1.8)) at week 4 which may be clinically meaningful.

Figure 3.

Mood states differences between older adult (N=16) vs. younger adult (N=38) intervention groups over time

Older adult patients had significantly lower Anger-Hostility POMS scores at all weeks except baselne, even though the overall POMS score for older adult and younger adult patients did not differ significantly.

*Weeks 4, 27, and 52 POMS Anger-Hostility scores statistically significant

Repeated measures techniques were utilized to identify changes post intervention while adjusting for baseline. Scores during weeks 4, 27 and 52 were modeled using baseline QOL scores and select covariates (primary cancer site, employment status, sex, grade, ECOG performance status). Results indicate that in the 24 models compiled, baseline QOL scores (N=24), performance status (N=11), tumor grade (N=4), sex (N=5), and age group (N=1) were the only contributing factors to the change in QOL over time post intervention.

DISCUSSION

Our findings suggest that a structured multidisciplinary intervention may help maintain and improve QOL for all patients with advanced cancer (Clark et al., 2013). Given that older patients experienced greater improvements in overall QOL, social WB and anger and hostility compared to younger patients, the intervention may be more effective for older patients than younger patients undergoing radiation therapy for advanced cancer. These results are contrary to our hypothesis that there would be no difference in response to the intervention between older and younger patients.

A large limitation to this analysis is the small sample size. Thus, the conclusions made here should not automatically be generalized to all patients with advanced cancer. However, the findings can give us an indication of patient needs and encourage inquiry into further research. Our results indicate that older patients receiving the intervention improved their QOL only at week 4 compared to younger patients for overall QOL and social WB but not the total QOL score. Older patients also had lower levels of anger and hostility at weeks 4, 27, and 52. Notably, younger patients did not experience any statistically significant improvement in QOL compared to the older patients throughout the study.

In the primary study, the overall group of older and younger adult patients receiving the intervention experienced statistically significant total QOL improvement when compared with the control group at 4 weeks, mostly attributed to improvements in physical WB. There were no differences compared to the control group with the single-item QOL or with mood scores (Clark et al., 2013). When analyzing the intervention group by age, differences were seen. Older adult patients and younger adult patients seemed to respond to the intervention differently in some ways.

Older adult patients improved their overall QOL as measured by LASA at week 4 but none of the other 10 individual QOL scales were significantly different, suggesting that there was no single domain that contributed more than others for the overall QOL improvement. Using a multidisciplinary intervention might have had a synergistic effect, impacting overall QOL more than the separate components, with older patients experiencing greater benefits.

Older patients showed a statistically better anger and hostility score compared to younger patients after the intervention. Intervention modalities that could have theoretically improved anger and hostility include relaxation training and spirituality, although there was no improvement in the Tension-Anxiety scale.

Our findings indicate that immediately post-intervention, older adult patients were able to maintain and in some scales improve QOL in comparison with younger adult patients, who experienced a decline in QOL. In the overall QOL and social WB, older adults reported improved scores immediately post intervention whereas younger adults reported lower scores. Our findings suggest that the intervention may have helped older adult patients mitigate or prevent decline in their QOL.

In two of the three scales, the differences between age groups were found at only the week 4 measures, whereas in the anger and hostility measure older adult patients sustained better scores from week 4 to the end of the study. Lack of maintenance of different effects between age groups over time could be due to several factors. Older patients may have benefited more from the intervention, but as time passed other QOL factors such as lower physical functioning or slower recovery negated this advantage. The intervention could have become less relevant over time after active cancer treatment ended, perhaps because its components focused on improving side effects of active treatment but negative effects of cancer treatment continued to impact QOL after active treatment ended. The six group sessions during active treatment may have been more effective at improving QOL than the telephone follow-up. Finally, if younger patients received cancer treatment that more negatively impacted their QOL, then after treatment ended their QOL may have improved more quickly than older patients’ QOL.

Overall, our findings support other reports that older patients with cancer generally have better QOL despite often having more physical impairment and less distress compared to younger patients (Akechi et al., 2012; Arndt et al., 2004; Schmidt et al., 2005; Wenzel et al., 1999). As people age, their perspectives and goals in life change and they may focus more on maintaining or achieving emotional balance rather than actively trying to influence situations (Blank and Bellizzi, 2008). These factors might lead to better emotional QOL, better coping, and less distress.

Another possible explanation for age-related QOL differences is that younger adult patients may have received more aggressive treatment than older adult patients, which could have more negatively impacted younger adult patients’ QOL. However, we found that primary cancer site did not affect the QOL score. Although we did not measure treatment intensity in our study, assuming that patients with the same cancer site received similar treatment our results do not indicate a difference in QOL score due to treatment factors.

Comparing our findings directly to other reports is difficult because of the heterogeneity of the literature. These other studies (1) utilize different rating scales for aspects of QOL and psychological distress; (2) contain different types of cancers and associated areas of disability, with the majority of studies on breast cancer; (3) include different severity of cancers in terms of stage, prognosis, and treatment; (4) define age cutoffs differently; and (5) use different rating scales (Newell et al., 2002; Raingruber, 2011; Rehse and Pukrop, 2003). In reviewing the literature it became apparent that more studies should be conducted and more results should be reported to build the evidence base surrounding interventions to improve QOL for cancer patients, especially regarding age-specific differences.

Our study is different in that it measured the outcomes of a multidisciplinary intervention to improve QOL, and few such intervention studies have been reported (Northouse et al., 2012). The intervention itself was unique because it addressed the five domains of QOL and was delivered by a large team composed of members from many disciplines. The intervention was based in a single cancer center, whereas other studies included multiple sites (see Raingruber, 2011 for a review).

There were limitations of our study. The primary study was conducted at a tertiary cancer center amongst a relatively homogenous ethnic and cultural background, which limits its generalizability. The secondary analysis of the intervention group by age resulted in smaller sample sizes, warranting cautious interpretation of statistical analysis. Because our intervention involved a multidisciplinary team, including psychiatry, psychology, physical therapy, nursing, social work, chaplain, and support from other disciplines, it may be difficult to perform at smaller medical centers.

In summary, older adult patients undergoing advanced cancer treatment significantly improved some aspects of their QOL, in areas different than younger adult patients, in response to a multidisciplinary intervention designed to impact QOL dimensions. Some of these benefits were immediate (overall QOL and social WB) and lasting (anger and hostility).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Melissa Rethlefsen, MLS, AHIP of the Mayo Clinic libraries assisted in compiling literature searches for the introduction and discussion. We would especially like to thank the patients who participated in this study and their families.

This study was conducted at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN. The findings were presented as a poster at the International Psychogeriatric Association International Meeting in Cairns, Australia on September 10, 2012.

Source of support: Linse Bock Foundation and St. Marys Hospital Sponsorship Board, Inc.

Sources of financial support for the research:

This work was supported by the Linse Bock Foundation and St. Marys Hospital Sponsorship Board, Inc.

Footnotes

Previous presentation: Poster presentation at the International Psychogeriatric Association International Meeting in Cairns, Australia on September 10, 2012.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None

DESCRIPTION OF AUTHORS’ ROLES

Megan M. Chock - Data analysis and interpretation of data, preparation of manuscript.

Maria I. Lapid - Data analysis and interpretation of data, preparation of manuscript.

Pamela J. Atherton - Data analysis, preparation of manuscript.

Simon Kung - Data analysis and interpretation of data, preparation of manuscript.

Jeff A. Sloan - Study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, preparation of manuscript.

Jarrett W. Richardson - Study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, preparation of manuscript.

Matthew M. Clark - Study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, preparation of manuscript.

Teresa A. Rummans - Study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, preparation of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Akechi T, et al. Perceived needs, psychological distress and quality of life of elderly cancer patients. Japanese Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;42:704–710. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hys075. doi:hys075 [pii] 10.1093/jjco/hys075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambs A, Warren JL, Bellizzi KM, Topor M, Haffer SC, Clauser SB. Overview of the SEER--Medicare Health Outcomes Survey linked dataset. Health Care Financing Review. 2008;29:5–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arndt V, Merx H, Stegmaier C, Ziegler H, Brenner H. Quality of life in patients with colorectal cancer 1 year after diagnosis compared with the general population: a population-based study. Journal of Clinincal Oncology. 2004;22:4829–4836. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.02.018. doi:22/23/4777 [pii] 10.1200/JCO.2004.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger NA, et al. Cancer in the elderly. Transactions of the American Clinical and Climatological Association. 2006;117:147–155. discussion 155-146. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blank TO, Bellizzi KM. A gerontologic perspective on cancer and aging. Cancer. 2008;112:2569–2576. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23444. doi:10.1002/cncr.23444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bretscher M, et al. Quality of life in hospice patients. A pilot study. Psychosomatics. 1999;40:309–313. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(99)71224-7. doi:10.1016/S0033-3182(99)71224-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cella DF, et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1993;11:570–579. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark MM, et al. Randomized controlled trial of maintaining quality of life during radiotherapy for advanced cancer. Cancer. 2013;119:880–887. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27776. doi:10.1002/cncr.27776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran SL, Andrykowski MA, Studts JL. Short Form of the Profile of Mood States (POMS-SF): Psychometric information. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7:80–83. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.7.1.80. [Google Scholar]

- Howlader N, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2009 (Vintage 2009 Populations) N. C. Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Koo K, et al. Do elderly patients with metastatic cancer have worse quality of life scores? Supportive Care in Cancer. 2012;20:2121–2127. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1322-6. doi:10.1007/s00520-011-1322-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapid MI, et al. Improving the quality of life of geriatric cancer patients with a structured multidisciplinary intervention: a randomized controlled trial. Palliative & Supportive Care. 2007;5:107–114. doi: 10.1017/s1478951507070174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locke DE, et al. Validation of single-item linear analog scale assessment of quality of life in neuro-oncology patients. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2007;34:628–638. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.01.016. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani G, et al. Evaluation by multidimensional instruments of health-related quality of life of elderly cancer patients undergoing three different "psychosocial" treatment approaches. A randomized clinical trial. Supportive Care in Cancer. 1996;4:129–140. doi: 10.1007/BF01845762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNair D, Lorr M, Droppelman L. Profile of Mood States: Manual. Educational and Testing Service; San Diego, CA: 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD. National Vital Statistics Reports: Deaths: Preliminary Data for 2010. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2012. National Vital Statistics Reports. [Google Scholar]

- Muss HB. Cancer in the elderly: a societal perspective from the United States. Clinical Oncology. 2009;21:92–98. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2008.11.008. doi:S0936-6555(08)00452-4 [pii] 10.1016/j.clon.2008.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newell SA, Sanson-Fisher RW, Savolainen NJ. Systematic review of psychological therapies for cancer patients: overview and recommendations for future research. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2002;94:558–584. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.8.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northouse LL, et al. Randomized clinical trial of a brief and extensive dyadic intervention for advanced cancer patients and their family caregivers. Psychooncology. 2012 doi: 10.1002/pon.3036. doi:10.1002/pon.3036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pocock SJ, Simon R. Sequential treatment assignment with balancing for prognostic factors in the controlled clinical trial. Biometrics. 1975;31:103–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puts MT, et al. Quality of life during the course of cancer treatment in older newly diagnosed patients. Results of a prospective pilot study. Annals of Oncology. 2011;22:916–923. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq446. doi:mdq446 [pii] 10.1093/annonc/mdq446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raingruber B. The effectiveness of psychosocial interventions with cancer patients: an integrative review of the literature (2006-2011) ISRN Nursing. 20112011:638218. doi: 10.5402/2011/638218. doi:10.5402/2011/638218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeve BB, et al. Impact of cancer on health-related quality of life of older Americans. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2009;101:860–868. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp123. doi:djp123 [pii] 10.1093/jnci/djp123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehse B, Pukrop R. Effects of psychosocial interventions on quality of life in adult cancer patients: meta analysis of 37 published controlled outcome studies. Patient Education and Counseling. 2003;50:179–186. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00149-0. doi:S0738399102001490 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose JH, Radziewicz R, Bowmans KF, O'Toole EE. A coping and communication support intervention tailored to older patients diagnosed with late-stage cancer. Clinical Interventions in Aging. 2008;3:77–95. doi: 10.2147/cia.s1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rummans TA, et al. Impacting quality of life for patients with advanced cancer with a structured multidisciplinary intervention: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24:635–642. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.209. doi:24/4/635 [pii] 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt CE, Bestmann B, Kuchler T, Longo WE, Kremer B. Impact of age on quality of life in patients with rectal cancer. World Journal of Surgery. 2005;29:190–197. doi: 10.1007/s00268-004-7556-4. doi:10.1007/s00268-004-7556-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent GK, Velkoff VA. The Next Four Decades: The Older Population in the United States: 2010 to 2050. U.S. Census Bureau; Washington, DC: 2010. Current Population Reports. [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel LB, et al. Age-related differences in the quality of life of breast carcinoma patients after treatment. Cancer. 1999;86:1768–1774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]