Abstract

Chronic hepatic encephalopathy (CHE) is a major complication in patients with severe liver disease. Elevated blood and brain ammonia levels have been implicated in its pathogenesis, and astrocytes are the principal neural cells involved in this disorder. Since defective synthesis and release of astrocytic factors have been shown to impair synaptic integrity in other neurological conditions, we examined whether thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1), an astrocytic factor involved in the maintenance of synaptic integrity, is also altered in CHE. Cultured astrocytes were exposed to ammonia (NH4Cl, 0.5–2.5 mM) for 1–10 days, and TSP-1 content was measured in cell extracts and culture media. Astrocytes exposed to ammonia exhibited a reduction in intra- and extracellular TSP-1 levels. Exposure of cultured neurons to conditioned media (CM) from ammonia-treated astrocytes showed a decrease in synaptophysin, PSD95 and synaptotagmin levels. CM from TSP-1 overexpressing astrocytes that were treated with ammonia, when added to cultured neurons, reversed the decline in synaptic proteins. Recombinant TSP-1 similarly reversed the decrease in synaptic proteins. Metformin, an agent known to increase TSP-1 synthesis in other cell types also reversed the ammonia-induced TSP-1 reduction. Likewise, we found a significant decline in TSP-1 level in cortical astrocytes, as well as a reduction in synaptophysin content in vivo in a rat model of CHE. These findings suggest that TSP-1 may represent an important therapeutic target for CHE.

Keywords: ammonia, astrocytes, chronic hepatic encephalopathy, synaptic proteins, thrombospondin-1

Introduction

Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is a major neurological complication in patients with severe liver disease. It is characterized by impaired neurological function and occurs in acute and chronic forms. The encephalopathy associated with acute HE (acute liver failure) generally occurs following massive liver necrosis, generally due to viral hepatitis, hepatic neoplasms, vascular causes or exposure to various hepatotoxins. It presents with the abrupt onset of delirium, seizures and coma, and has an extremely poor prognosis (70% mortality) (Lee 2012; Shawcross and Wendon 2012). HE in the setting of chronic liver disease (chronic HE, CHE) generally occurs as a consequence of cirrhosis of the liver, usually secondary to alcoholism (Wakim-Fleming 2011). CHE is characterized by confusion, disorientation, behavioral changes, impaired cognition, inverted sleep-wake cycles, and motor disturbances. The molecular basis for the neuropsychiatric disorder in CHE remains elusive (Mullen and Prakash 2012; Patel et al. 2012).

Neuronal dysfunction is a well established finding in CHE (Cauli et al. 2009). Increased synthesis of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and subsequent alterations in GABA-ergic neurotransmission, as well as an increase in endogenous benzodiazepines (which modulate GABA-mediated neurotransmission), have been proposed to be involved in CHE (Llansola et al. 2012). Inhibition of cortical function and the subsequent behavioral defects from altered GABA-ergic signaling have also been postulated as major mechanisms leading to CHE (Bismuth et al. 2011).

HE is one neurological disorder in which, early on, astrocytes were suggested to play a vital role (Norenberg 1968). A major factor in the pathogenesis of HE are elevated blood and brain ammonia levels due to the inability of the injured liver to detoxify ammonia by the synthesis of urea. Once in brain, ammonia is metabolized to glutamine by the action of glutamine synthetase, a process that in brain only occurs in astrocytes (Norenberg 1979). It is therefore of interest that the principal histopathological finding in CHE is the presence of Alzheimer type II astrocytosis. These astrocytes are characterized by the presence of pale and enlarged astrocytic nuclei (often found in pairs), along with margination of nuclear chromatin and the presence of prominent nucleoli (Norenberg 1979). While the significance of this astrocytic change is incompletely understood, abundant data strongly suggest that Alzheimer type II astrocytes are dysfunctional cells (Norenberg 1987; Norenberg et al. 1998). This led to the concept that HE fundamentally represents a primary astrogliopathy (Norenberg 1987; Norenberg et al. 1998).

Astrocytes play a crucial role in the central nervous system by regulating a number of critical processes, including synaptogenesis, synaptic function, modulation of neurotransmission, regulation of pH, ion and water homoeostasis, energy metabolism, defense against oxidative stress and the detoxification of ammonia, metals and other toxins (Norenberg 1987; Bélanger and Magistretti 2009; Wang and Bordey 2008). Astrocytes are also involved in the provision of growth factors and nutrients to neurons and other neural cells (Wang and Bordey 2008), as well as in the formation and maintenance of the blood-brain barrier (Abbott et al. 2006).

One potential mechanism by which defective astrocytes may impact neuronal integrity is through a reduction in thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1) levels. Astrocytes are known to synthesize and secrete TSP-1 (Christopherson et al. 2005; Tran and Neary 2006), and a reduction in TSP-1 expression by siRNA silencing was reported to decrease neuronal synaptophysin protein expression (Yu et al. 2008). Such reduction in TSP-1 and synaptophysin protein levels were associated with behavioral abnormalities in experimental models of stroke (Liauw et al. 2008; Lin et al. 2003), Alzheimer disease (Buée et al. 1992), and Down’s syndrome (Garcia et al. 2010).

This study examined intra- and extracellular levels of TSP-1 in ammonia-treated cultured astrocytes, and the effect of conditioned media (CM) from ammonia-treated astrocytes on synaptic protein levels in cultured neurons. A significant decrease in TSP-1 protein level was observed in ammonia-treated astrocyte cultures. We also found a reduction in synaptophysin protein levels when cultured neurons were exposed to conditioned media (CM) from ammonia-treated astrocytes, and that enhancing intra- and extracellular levels of astrocytic TSP-1 reversed the synaptophysin loss. We further observed a significant decline in astrocytic TSP-1, and in neuronal synaptophysin levels in a rat model of CHE. Our findings suggest that dysfunctional astrocytes resulting from ammonia treatment negatively impacts neuronal synaptic integrity, thereby contributing to the neurological abnormalities associated with CHE.

Materials and methods

Astrocyte cultures

Primary cultures of cortical astrocytes were prepared from brains of 1- to 2-day-old rat pups by the method of Ducis et al. (1990). Briefly, cerebral cortices were freed of meninges, minced, dissociated by trituration and vortexing and were seeded onto 35 mm culture dishes in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing penicillin, streptomycin and 15% fetal bovine serum. The culture plates were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 and 95% air. Culture media were changed twice weekly. On day 10 post-seeding, fetal bovine serum was replaced with 10% horse serum. After 14 days, cultures were treated with 0.5 mM dibutyryl cAMP (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) to enhance cellular differentiation (Juurlink and Hertz 1985). Cultures consisted of at least 95% astrocytes as determined by glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) immunohistochemistry. All cultures used were 21–23 days old.

All procedures followed guidelines established by the National Institute of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by our Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

Neuronal cultures

Cortical neuronal cultures were prepared by a modification of the method described by Schousboe et al. 1989. Briefly, cortices were removed from 16–18 day old rat fetuses and placed in DMEM-high glucose (30 mM) containing 25 mM KCl and 10% horse serum. The tissue was minced and mechanically dissociated with a pipette. Approximately 1–2 × 106 cells per ml were seeded onto poly-D-lysine coated 35 mm culture dishes. To prevent the proliferation of astrocytes, cytosine arabinoside (10 µM) was added to the culture medium 48 hours after seeding. These cultures consist of at least 90% neurons as determined by immunohistochemical staining for neurofilament protein; the remaining cells were chiefly astrocytes. Experiments were performed on cultures that were 7–8 days-old.

TSP-1 overexpression in cultured astrocytes

To examine whether exposure of cultured neurons to CM from ammonia-treated astrocytes in which TSP-1 is overexpressed diminishes or prevents the reduction in synaptic proteins, we overexpressed TSP-1 in cultured astrocytes. Briefly, astrocytes were transfected with TSP-1 cDNA (tagged with the pIRES2-AcGFP1 vector; GENEWIZ Inc, South Plainfield, NJ). Cultures were exposed to different concentrations of TSP-1 cDNA (50, 100 and 250 ng/2.5×105 cells) for 72 hrs. Mirus TransIT-TKO transfection reagent was used to transfect TSP-1 following the manufacturer instructions (Mirus, #MIR 2150). At the end of transfection, the culture media were replaced with normal media. These cultures were treated with and without ammonia for 10 days, and at the end of treatment, intra- and extracellular levels of TSP-1 were measured by Western blots. The empty vector, as well as the transfection reagent alone, was used as controls for all experiments.

Immunohistochemistry of TSP-1 and synaptophysin in CHE

Control and TAA-treated rats (four animals each) were anesthetized at the end of TAA treatment with a mixture of ketamine (80 mg/kg) and xylacine (20 mg/kg), and were then transcardially perfused with heparinized saline for 1 min, followed by fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min. After decapitation, heads were left in the same fixative for an additional 24 h at RT. Brains were cryoprotected (12–24 h) in 30% sucrose. Cortical sections (20 micron-thick) were obtained with a cryostat; sections were blocked with 10% goat serum and incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-synaptophysin antibody (rabbit monoclonal, YE269, 1:150 dilution; cat# 32127, Abcam, Cambridge, MA), BA24 anti-thrombospondin (TSP-1) antibody (mouse monoclonal A6.1, 1:100 dilution; Millipore, Billerica, MA), and anti-GFAP antibody (astrocyte marker, 1:150 dilution, cat# ab7260, Abcam, Cambridge, MA), as previously described (Jayakumar et al. 2014). Following incubation with primary antibodies, sections were washed with tris-buffered saline containing 1% Tween-20 (TBS-T) and incubated with fluorescent HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies [(1:500; Alexa Flour-546 goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) for GFAP, Alexa Flour-488 goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) for TSP-1, and Alexa Flour-488 goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) for synaptophysin)], for 2 h. Sections were then covered with commercial mounting media (Vector Labs., Burlingame, CA) containing DAPI (nuclear stain). Immunofluorescent images were acquired with a Zeiss LSM510/UV Axiovert 200M confocal microscope with a plan apochromat 40x objective lens, and a 2x zoom resulting in images 125×125 µm in area and 1.0 µm optical slice thickness (1.0 Airy units for Alexa Fluor 546 or 568 emission channel). Random collection of images from sections of control and TAA-treated rats was achieved by systematically capturing each image in a “blinded” manner by moving the microscope stage approximately 5 mm in four different directions. At least 17 fluorescent images were captured per rat, and the images merged to localize astrocytic TSP-1 protein. TSP-1 and synaptophysin levels in cultured neurons and in brain sections were quantified using the Volocity 6.0 High Performance Cellular Imaging Software (PerkinElmer) as described previously (Jayakumar et al. 2014; Rick et al. 2013), and normalized to the number of DAPI-positive cells, as well as to the intensity of DAPI.

Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed and repeated four to six times using cells derived from different batches of astrocyte and neuronal cultures. Five to six individual culture plates were used in each experimental group for TSP-1, and 4–6 for synaptophysin measurements. Six animals from each group were used for in vivo studies. Data of all experiments were subjected to analysis of variance followed by Tukey's post hoc comparisons. A value of p<0.05 was considered significant. Error bars, mean ± S.E.

Results

Intra- and extracellular TSP-1 in cultured astrocytes after treatment with ammonia

Primary cultures of rat cortical astrocytes treated with ammonia were used in this study. The use of such cultures as a model of HE is highly appropriate since substantial evidence invokes a crucial role of ammonia in the pathogenesis of HE, and astrocytes are the principal cells affected in this condition (Norenberg et al. 2009). Moreover, many of the findings occurring in HE in vivo are also observed in ammonia-treated astrocyte cultures, including characteristic morphologic changes, cell swelling, defects in glutamate transport, up-regulation of the 18 kDa translocator protein (TSPO), reduction in levels of glial fibrillary acidic protein (Sobel et al. 1981; Kretzschmar et al. 1985; Kimura and Budka 1986) and myo-inositol (Norenberg et al. 2009), disturbance in energy metabolism, and evidence of oxidative/nitrative stress (Lange et al. 2012).

Pathophysiological concentrations of ammonia (0.5, 1.0 and 2.5 mM NH4Cl) (Singh and Trigun 2010; Dejong et al. 1993; Carbonero-Aguilar et al. 2011) were added to astrocyte cultures for different time periods (1, 5 and 10 days with regular media changes, once in two days for both 5 and 10 day treatment). At the end of treatment (24 h after the addition of last ammonia exposure), TSP-1 protein levels in the cell extracts and culture media were measured by Western blots. Fresh addition of inhibitors and antioxidants were performed with each change of culture medium during the entire period of incubation.

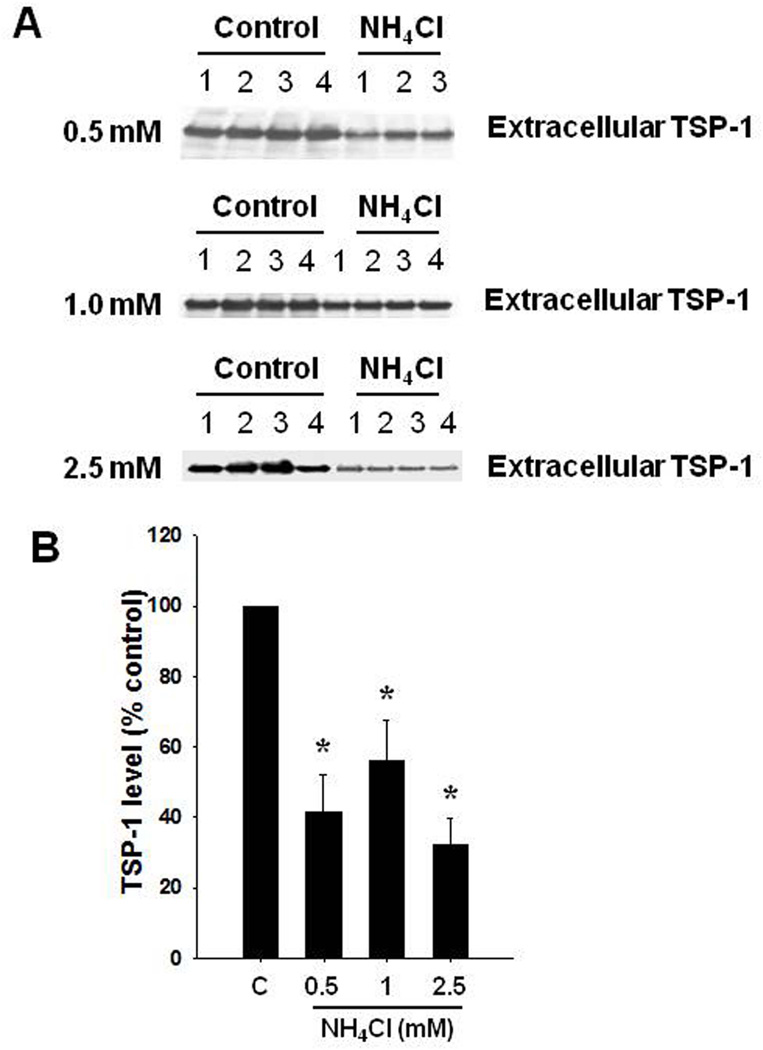

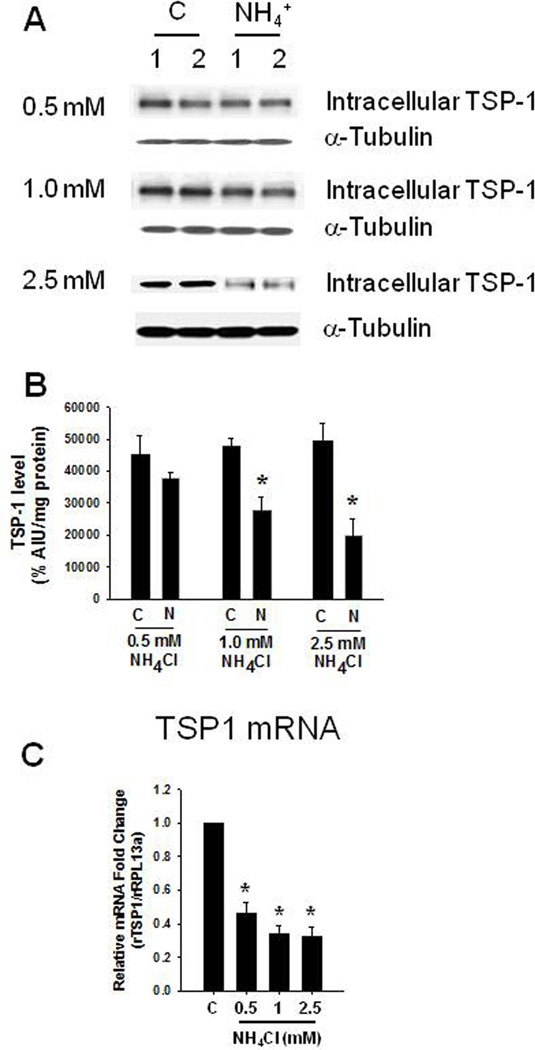

Exposure of astrocytes to 0.5, 1.0 and 2.5 mM NH4Cl for 10 days caused a reduction in extracellular TSP-1 levels (58.6, 43.9 and 67.5%, respectively) (Figure 1). Intracellular TSP-1 levels were also reduced (16.2, 57.4, 40.7%, respectively) (Figure 2). We additionally found a significant decline in TSP-1 mRNA level when astrocytes were exposed to 0.5, 1.0 and 2.5 mM ammonia for 10 days (Figure 2C).

FIGURE 1.

Extracellular TSP-1 level after a 10-day treatment of cultured astrocytes with 0.5–2.5 mM ammonia (NH4Cl). (A) Representative Western blots from cell culture media of ammonia-treated astrocytes show a significant decrease in TSP-1 levels. (B) Quantification of ammonia-induced changes in TSP-1 protein levels. *p<0.05 vs. control. C, control; NH4+, ammonia.

FIGURE 2.

Intracellular TSP-1 level after a 10-day treatment of cultured astrocytes with 0.5–2.5 mM ammonia. (A) Representative Western blots from ammonia-treated astrocytes (1 and 2.5 mM) show a significant decrease in intracellular TSP-1 levels. (B) Quantification of NH4Cl-induced changes in TSP-1 protein. TSP-1 levels were normalized against α-tubulin. (C) TSP-1 mRNA expression after ammonia treatment. *p<0.05 vs. control. C, control; N, NH4Cl.

Exposure of astrocytes to 0.5 and 1.0 mM ammonia for 5 days had no effect on extra- (data not shown) or intra-cellular TSP-1 levels (Suppl. Figure 2A). However, exposure to 2.5 mM ammonia significantly reduced TSP-1 levels by 51.6% (Suppl. Figure 2, A and B). Although TSP-1 protein levels were not altered in 0.5 and 1.0 mM ammonia-treated astrocytes, a significant decline in TSP-1 mRNA level was observed at these ammonia concentrations (Suppl. Figure 2C).

Hevin is another matricellular protein that is known to influence neuronal synaptic integrity in other conditions (Kucukdereli 2011). Its level also decreased in ammonia-treated cultured astrocytes (intra- and extracellular levels by 35.7 and 31.1%, respectively, n=5, p<0.05 vs. control). Since decreased transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β1) was shown to influence TSP-1 levels (McGillicuddy et al. 2006; Okamoto et al. 2002; Mimura et al. 2005), we examined whether ammonia also influenced TGF-β1 levels. A reduction (57.8%) in intracellular levels of TGF-β1 was detected when astrocytes were treated with ammonia (Suppl. Figure 3). The reduction in the level of hevin, however, was of a lesser magnitude than that observed with TSP-1.

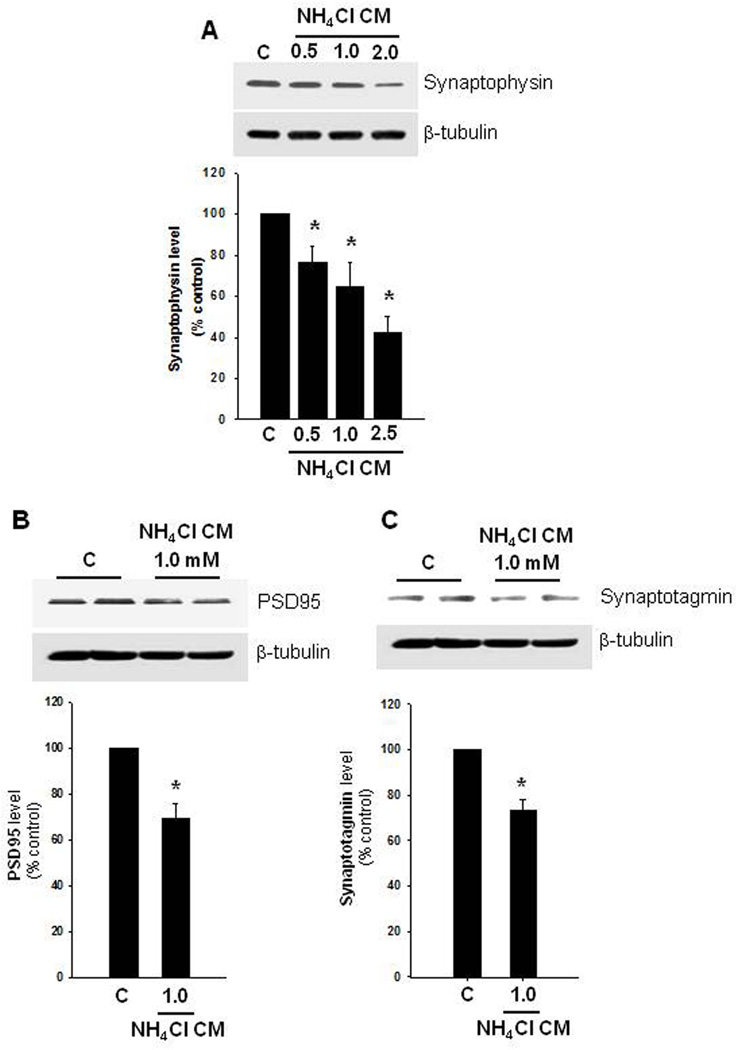

Effect of conditioned media (CM) from ammonia-treated astrocytes on neuronal synaptic proteins

We examined whether an ammonia-induced decline in extracellular TSP-1 concentration contributes to a reduction in neuronal synaptophysin. Accordingly, cultured astrocytes were treated with ammonia (0.5, 1.0 and 2.5 mM, NH4Cl) for 10 days, and at the end of treatment, 1 ml of CM from ammonia-treated astrocytes was added to neuronal cultures. Synaptophysin level was determined 24 h later by immunofluorescence and Western blots. Cultured neurons exposed to CM from 0.5–2.5 mM NH4Cl-treated astrocytes showed a significant reduction in synaptophysin levels in a dose-dependent manner, as measured both by immunofluorescence (Suppl. Figure 4, A–E) and Western blots (Figure 3A), which corresponded well with levels of TSP-1 reduction. Quantification of the immunocytochemistry data also corresponded well with findings in Western blots (Suppl. Figure 4E and Figure 3A). While CM from ammonia-treated astrocytes (0.5–2.5 mM) reduced synaptophysin levels, the extent of reduction among the three ammonia-treated groups was not statistically significantly different from each other. Exposed neuron cultures to CM from control astrocytes had no effect on synaptophysin protein levels (data not shown).

FIGURE 3.

Synaptophysin, PSD95 and synaptotagmin protein levels in cultured neurons. (A) Representative Western blots from astrocytes treated with ammonia (0.5–2.5 mM) for 10 days and the conditioned media (CM) added to neurons for 24 h. Such treatment led to a significant reduction in synaptophysin in a dose-dependent manner. (B) CM from ammonia-treated astrocytes also decreased PSD95, and synaptotagmin levels (C). *p<0.05 vs. control. C, control.

It should be emphasized that the direct exposure of cultured cortical neurons to 0.5–2.5 mM ammonia for 24 h had no significant effect on synaptophysin level. Additionally, we found no residual ammonia in the ammonia-treated astrocytic CM (at 24 h) that was subsequently applied to cultured neurons. We also found no detectable levels of ammonia 2 h after exposure of cultured astrocytes to ammonia (Jayakumar et al., 2006). This absence of ammonia is likely due to a rapid conversion of ammonia into glutamine via glutamine synthetase activity (Cooper et al. 1979). These findings indicate that the ammonia-mediated reduction in neuronal synaptophysin levels is due to an effect of ammonia on astrocytes, and not to a direct effect of ammonia on neurons.

We also examined whether PSD95, a post-synaptic density protein, and synaptotagmin-1, a Ca2+ sensor in the membrane of the pre-synaptic axon terminal, which has also been implicated in the maintenance of synaptic integrity, were similarly affected by CM from ammonia-treated astrocytes. We indeed found that when cultured neurons were exposed to CM from ammonia-treated astrocytes (1.0 mM, 10 d), decreased levels of PSD95 (32.7%), and synaptotagmin-1 (26.8%) (Figure 3 B and C) were observed. However, the extent of reduction in PSD95 and synaptotagmin-1 levels were less than that observed in synaptophysin. Further, the direct exposure of cultured neurons to ammonia (1 mM, 24 h) had no significant effect on PSD95 protein levels (data not shown).

CM from TSP-1 overexpressing cultured astrocytes that were treated with ammonia, when added to cultured neurons, reversed the decrease in synaptic proteins

We then examined whether the effect of CM from ammonia-treated cultured astrocytes on the decline in levels of neuronal synaptic proteins is indeed due to diminished astrocytic TSP-1 levels. TSP-1 was overexpressed (with 100 and 250 ng/ml TSP-1 cDNA) in cultured astrocytes. CM from TSP-1 overexpressed cells that were treated with ammonia (1 mM, 10 d) showed a significant increase in extracellular levels of TSP-1 (1.2–1.5-fold more than the effect of CM from ammonia-treated astrocytes that were exposed to an “empty” vector or with the transfection reagent alone). Exposure of cultured cortical neurons to CM from ammonia-treated astrocytes showed a reduction in synaptic proteins. On the other hand, exposure of neurons to CM from ammonia-treated astrocyte cultures that had been transfected with 250 ng TSP-1 cDNA, led to a lesser reduction in synaptophysin, PSD95 and synaptotagmin content by 73.5, 65.9 and 78.2 %, respectively (n=4, p<0.05 vs. respective controls).

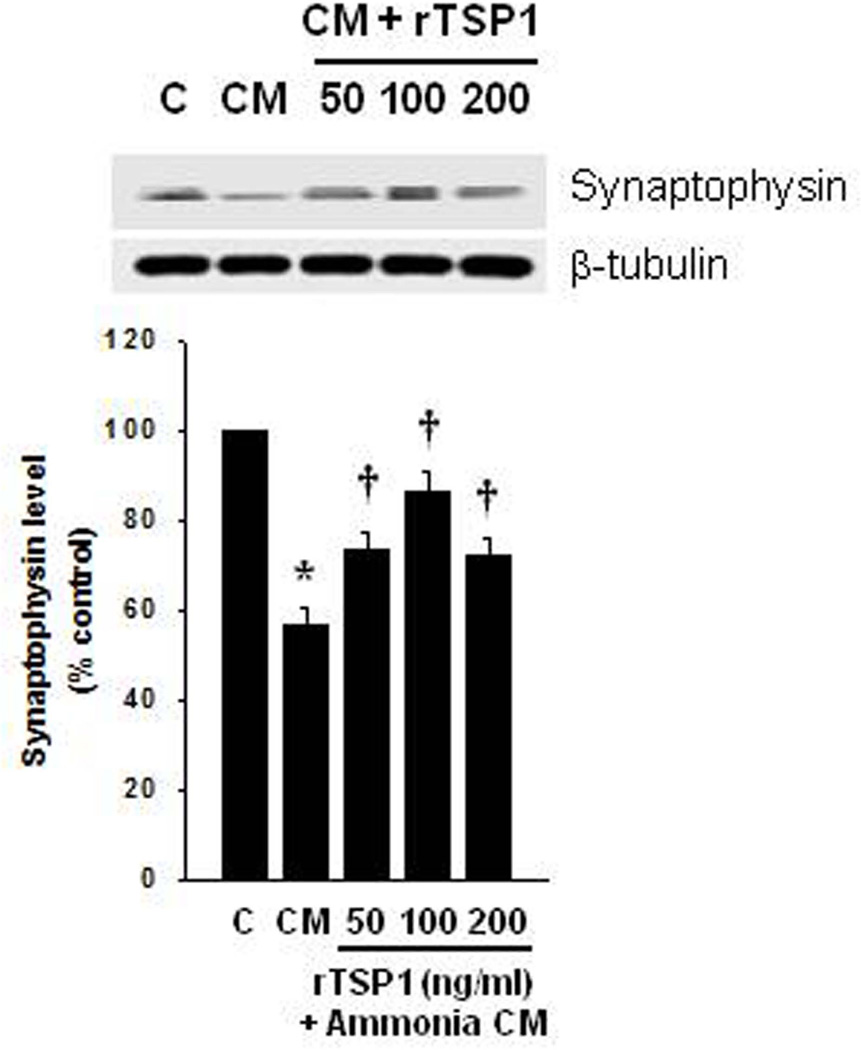

We also examined whether the addition of recombinant TSP-1 (rTSP-1) also prevented the effect of CM from ammonia-treated (1.0 mM) cultured astrocytes on the synaptophysin loss in neurons. For this purpose, cultured cortical neurons where exposed to CM from ammonia-treated (1.0 mM) cultured astrocytes, along with recombinant TSP-1 (rTSP-1; 50, 100, 200 ng/ml) for 24 h, and levels of synaptophysin were measured by Western blots. Neurons exposed to CM from ammonia-treated astrocytes showed a 43.6% reduction in synaptophysin content, and such effect was significantly reversed by 50, 100 and 200 ng/ml rTSP-1 (39.5, 68.7 and 35.6%, respectively) (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Effect of recombinant TSP-1 (rTSP-1) on synaptohysin level. (A) Representative Western blots from cultured astrocytes treated with ammonia (1.0 mM) for 10 days and the CM was then added to cultured neurons for 24 h, along with rTSP-1. Such treatment caused a reversal of the synaptophysin loss. *p<0.05 vs. control. †p<0.05 vs. CM from ammonia-treated (1.0 mM) astrocytes. C, control; CM, conditioned medium.

Additionally, we investigated whether depletion of TSP-1 in the astrocytic CM affects neuronal synaptophyin content. We found that, TSP-1 levels in the CM of astrocytes were depleted by immunoprecipitation. The resulting CM when added to cultured neurons (for 24 h) exhibited a significant loss of synaptophysin content (43.6%), supporting the concept that TSP-1 is involved in the maintenance of synaptophysin levels in CHE.

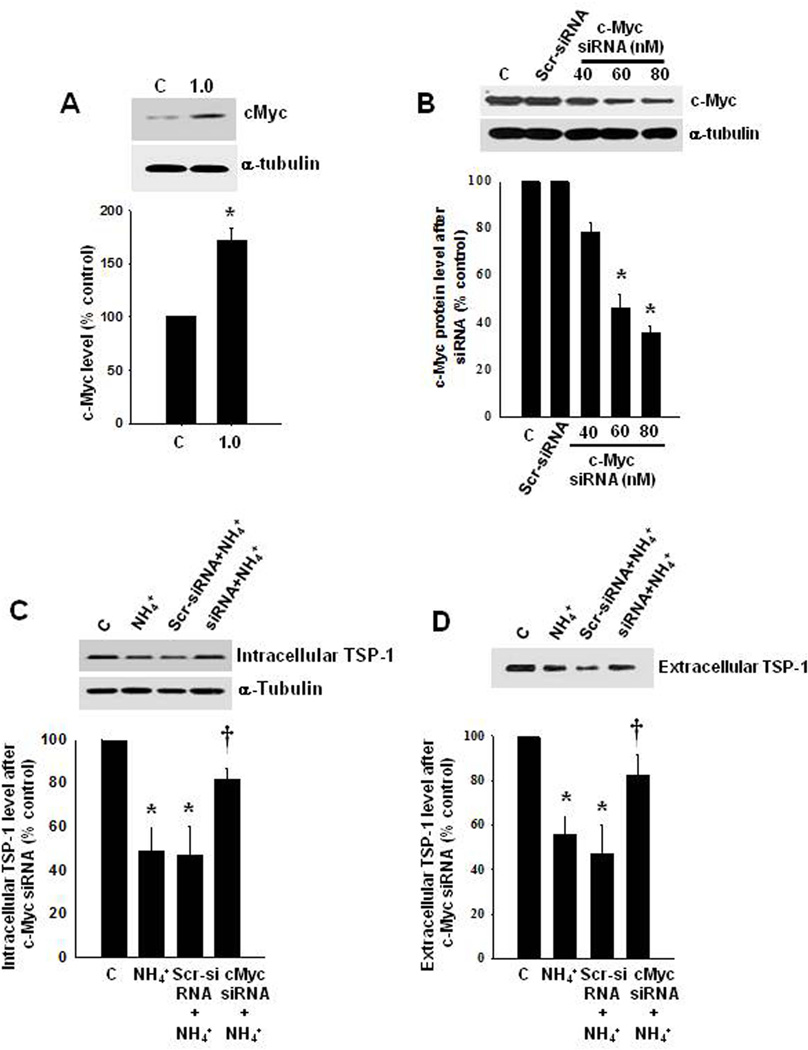

Effect of c-Myc on TSP-1 level after ammonia treatment to cultured astrocytes

c-Myc is a transcription factor expressed in astrocytes in vitro and in vivo (Liu et al. 2006; Saljo et al. 2002), and its overexpression was shown to cause a decrease in TSP-1 protein by exerting a repressor effect on TSP-1 mRNA (Watnick et al. 2003). We therefore examined whether c-Myc contributes to the ammonia-induced reduction in TSP-1. Exposure of cultured astrocytes to ammonia (1 mM, 10 d) increased levels of c-Myc protein by 86.2% (Figure 5 A).

FIGURE 5.

Effect of c-Myc on TSP-1 expression. (A) Representative Western blot from ammonia-treated astrocytes shows a significant increase in c-Myc protein. (B) Treatment with c-Myc siRNA significantly reduced c-Myc concentration. (C and D) Inhibition of c-Myc by siRNA significantly increased intra- and extracellular TSP-1 protein level. *p<0.05 vs. control; †p<0.05 vs. scrambled control. C, control; NH4+, ammonia; Scr, scrambled control (control siRNA).

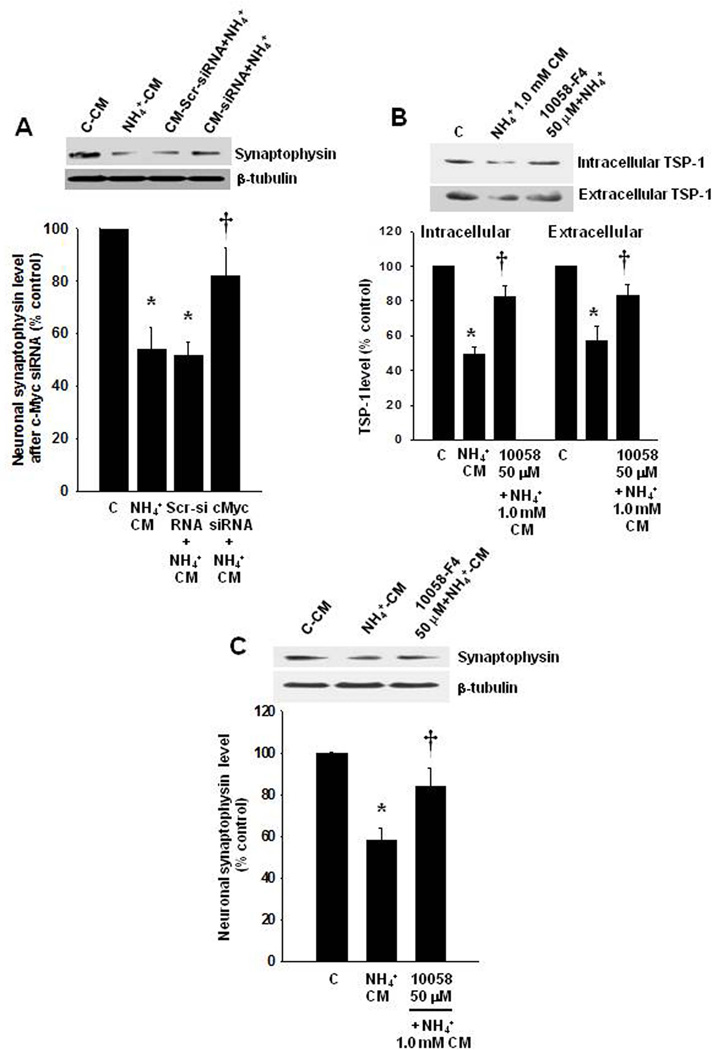

We then examined whether silencing c-Myc with siRNA prevents or diminishes the reduction in TSP-1 levels by ammonia. c-Myc was silenced in cultured astrocytes with siRNA as previously described (Lu and Hong, 2009), and found that transfection with 40, 60 and 80 nM of c-Myc siRNA significantly reduced the concentration of c-Myc (by 47.8, 69.4 and 76.5%, respectively) (Figure 5 B). Exposure of c-Myc-silenced cells (80 nM siRNA) to 1 mM ammonia (10 days) caused a 64 and 60% recovery in intra- and extracellular levels of TSP-1, respectively (Figure 5 C and D) (n=5, p<0.05 vs. respective controls) as compared to the effect of ammonia on scrambled siRNA-treated cells, which showed a 40–45% reduction in TSP-1. Exposure of cultured neurons (24 h) to CM from ammonia-treated astrocytes (10 d) in which the c-Myc-gene was silenced, resulted in a reduction in the level of synaptophysin (by 61%) (Figure 6 A).

FIGURE 6.

Effect of astrocytic c-Myc inhibition on neuronal synaptophysin levels. (A-C) Astrocytes in which the c-Myc-gene was silenced, or exposed to a c-Myc inhibitor, 10058-F4, along with ammonia and the CM then added to cultured neurons (for 24 h) resulted in a lesser reduction in synaptophysin level. *p<0.05 versus control; †p<0.05 versus scrambled control. C, control; NH4+, ammonia; Scr, scrambled control (control siRNA); CM, conditioned media.

We also examined whether a pharmacological inhibition of c-Myc prevents or diminishes the reduction in TSP-1 levels by ammonia. We found that treatment of astrocytes with ammonia plus 10058-F4 (50 µM), an inhibitor of c-Myc, for 10 days enhanced intra- and extracellular TSP-1 levels by 64.2 and 61.2%, respectively (Figure 6 B). Higher doses of 10058-F4 (100 and 150 µM) showed no additional effect (data not shown). Further, exposure of cultured neurons (24 h) to CM from ammonia-treated astrocytes (10 d) in which c-Myc was inhibited by 10058-F4, caused a reversal of the synaptophysin loss (59.4%), as compared to the effect of CM only from ammonia-treated astrocytes (Figure 6 C).

Attenuation of the ammonia-induced inhibition of TSP-1 by antioxidants and a nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) inhibitor

A considerable body of evidence suggests that the formation of reactive oxygen/nitrogen species and the resulting oxidative/nitrative stress (ONS) plays a major role in HE (Jayakumar and Norenberg 2012). Additionally, activation of the transcription factor NF-κB was identified in ammonia-treated cultured astrocytes (Schliess et al. 2002; Sinke et al. 2008). Since ONS and NF-κB have been strongly implicated in the mechanism of TSP-1 downregulation in other conditions (Chen et al. 2011; De Stefano et al. 2009; Tan et al. 2009), we examined whether ONS and NF-κB are likewise involved in the mechanism of the ammonia-induced reduction in TSP-1 levels in cultured astrocytes. Astrocyte cultures were treated with the antioxidants Mn(III) tetrakis (4-benzoic acid) porphyrin (MnTBAP, 10 µM), dimethylthiourea (DMTU, 100 µM), and the nitric-oxide synthase (NOS) inhibitor L-NAME (250 µM), as well as SN50 (0.5–1.0 µM), an inhibitor of NF-κB, along with ammonia (1.0 mM) for 10 consecutive days (with regular media changes), and the level of TSP-1 in the culture media was determined by Western blots. MnTBAP, DMTU and L-NAME significantly reduced the inhibition of TSP-1 level in the culture media after exposure to 1.0 mM ammonia (Suppl. Figure 5 A). Similarly, SN50 significantly reduced the inhibition of extracellular TSP-1 level after exposure to 1.0 mM ammonia (Suppl. Figure 5 B). These findings indicate that ONS and the activation of NF-κB indeed contribute to the ammonia-induced inhibition of TSP-1 release.

The effect of antioxidants on the ammonia-induced reduction in TSP-1 mRNA expression was also examined in cultured astrocytes. Treatment of astrocytes with MnTBAP (10 µM), (DMTU, 100 µM) and L-NAME (250 µM) significantly diminished the ammonia-induced reduction in TSP-1 mRNA (Suppl. Figure 5 C), suggesting that the reduction in TSP-1 levels in ammonia-treated astrocytes is due to a defective transcriptional regulation of TSP-1 by ONS.

We further examined whether an agent known to enhance TSP-1 synthesis and release, is capable of reversing the ammonia-induced reduction in TSP-1. For this purpose, we investigated the effect of metformin, a commonly used anti-diabetic agent that is known to enhance the release of TSP-1 (Tan et al. 2009). Metformin was also shown to exert a protective effect in diabetic patients who also had hepatic encephalopathy (Ampuero et al., 2012). We found that metformin (25 µM) diminished the ammonia-induced reduction in intra- and extracellular levels of TSP-1 in astrocytes (by 77.3 and 68.9%, respectively, p<0.05 vs. ammonia group). Further, exposure of cultured neurons (24 h) to CM from ammonia-treated astrocytes (10 d) in which TSP-1 levels were enhanced by metformin, caused an elevation in synaptophysin levels by 65.8% (p<0.05), as compared to the effect of CM astrocytes treated only with ammonia.

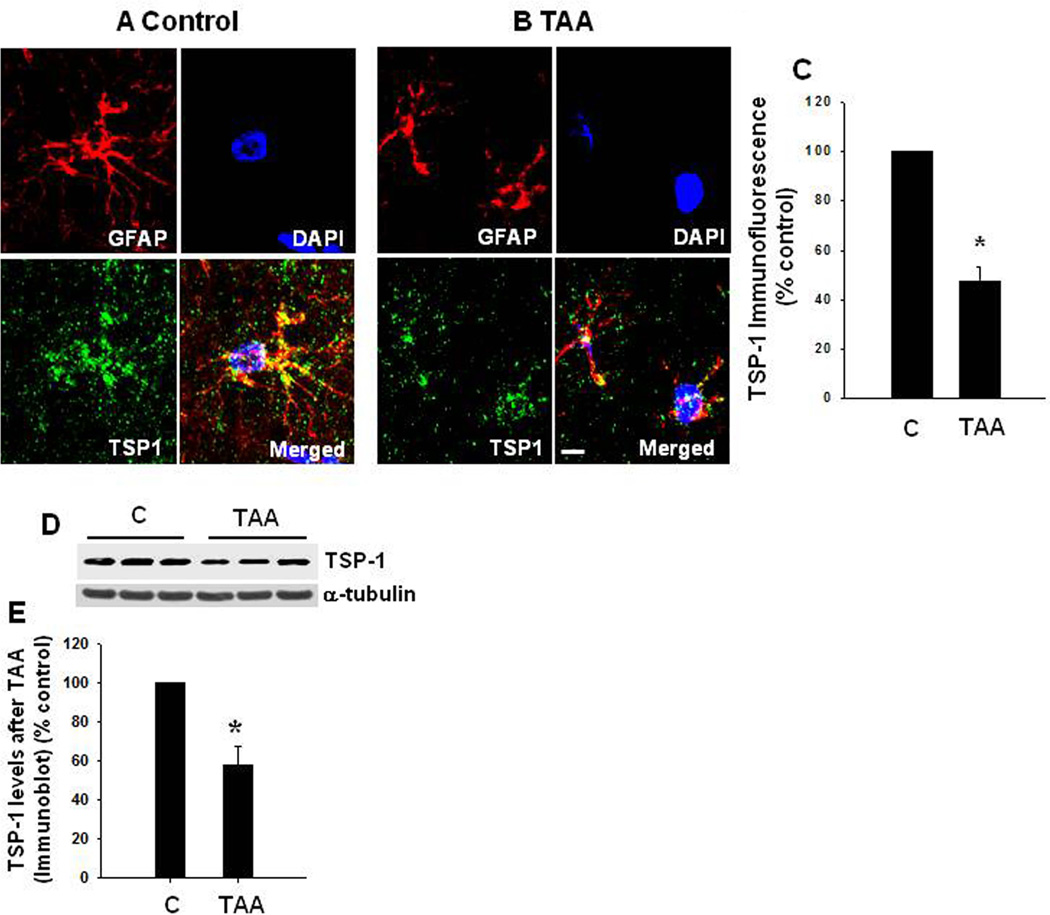

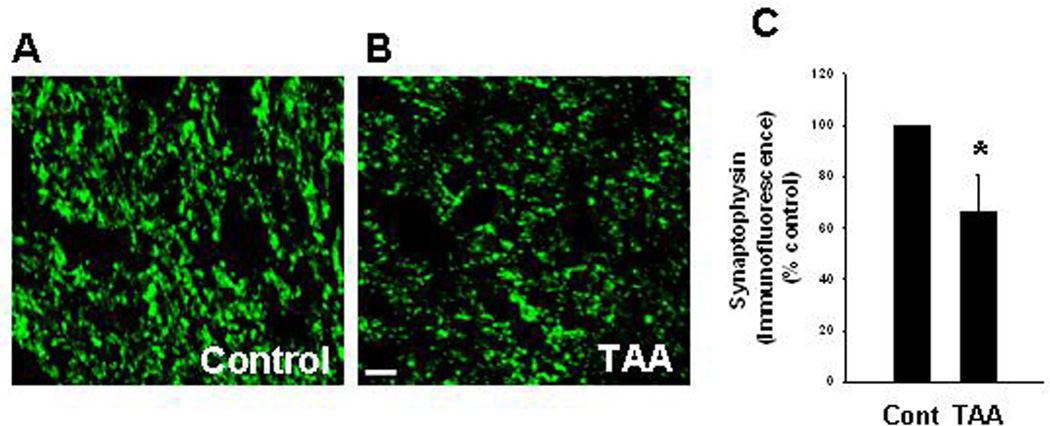

TSP-1 and synaptophysin levels in cerebral cortex of rats with CHE

To examine whether comparable alterations in TSP-1 and synaptophysin protein level also occur in an in vivo model of CHE, rats were treated with the liver toxin thioacetamide (TAA, 100 mg/kg b. wt) for 10 days, and the extent of TSP-1 and synaptophysin protein expression in cortical sections were examined. To identify changes in TSP-1 in astrocytes, sections were co-immunostained with GFAP (astrocyte marker) and DAPI (nuclear marker), and the degree of immunofluorescence examined with a confocal laser scanning microscope. A significant reduction (52.4%) in TSP-1 fluorescence was detected in astrocytes from TAA-treated rats as compared to control rats (Figure 7 A , B and C). We also found a comparable reduction in synaptophysin protein in cortical sections of rats treated with TAA (Figure 8). A slight reduction in GFAP fluorescence was identified in TAA-treated rats (Figure 7). Such reduction was previously reported in humans with HE, as well as in ammonia-treated cultured astrocytes (Sobel et al. 1981; Kretzschmar et al. 1985; Kimura and Budka 1986). However, we did not observe a significant change in the total number of astrocytes in this in vivo model of CHE as measured by counting of astrocyte nuclei (stained with DAPI) that are co-stained with GFAP. Additionally, it should be noted that a decrease in the number of astrocytes is not a feature of humans with chronic HE (Norenberg et al., 1992). We also measured TSP-1 level in cerebral cortex of TAA-treated rats by Western blots. Cortical tissues from rats treated with TAA for 3 days showed a significant decline in TSP-1 content (42.3% decrease, as compared to control; n=5) (Figure 12 D and E), which corresponded well with data obtained by immunofluorescence.

FIGURE 7.

TSP-1 protein levels in astrocytes from cerebral cortex of rats with CHE following the administration of the hepatotoxin thioacetamide (TAA, 100 mg/kg) for 10 days. (A) Control brain: glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP, red, astrocytes), TSP-1 (green), and DAPI (blue, nuclei). The co-localization (merged) image of TSP-1 and GFAP illustrates the enrichment of TSP-1 in astrocytes. (B) TAA-treated rat brain showed a reduction in astrocytic TSP-1 content. (C) Relative quantification of TSP-1 immunofluorescence staining. Scale bar = 20 µm. (D). Cortical TSP-1 level after a 10-day treatment of rats with TAA. Representative Western blots from TAA-treated rats show a significant decrease in intracellular TSP-1 level. (E) Quantification of TSP-1 immunoblots.*p<0.05 vs. control. C, control.

FIGURE 8.

Synaptophysin level in cerebral cortex of rats with CHE following the administration of the hepatotoxin thioacetamide (TAA) for 10 days. (A) Synaptophysin level in control (normal) brain. (B) A significant reduction in synaptophysin level was found in TAA-treated rats as compared to control animals. (C) Relative quantification of synaptophysin immunofluorescence staining. *p<0.05 vs. control. Cont, control. TAA, thioacetamide. Scale bar = 20 µm.

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that chronic ammonia toxicity in cultured astrocytes results in decreased extracellular levels of TSP-1. Additionally, synaptophysin levels declined in cultured neurons after exposure to conditioned media (CM) derived from ammonia-treated astrocytes, and such effect was diminished when recombinant TSP-1 (rTSP-1) was added to the CM of ammonia-treated astrocytes. We also found decreased levels of other synaptic proteins (PSD95 and synaptotagmin-1), when neurons were exposed to CM derived from ammonia-treated astrocytes. Increased c-Myc protein content was detected in ammonia-treated astrocytes, while silencing c-Myc or pharmacological inhibition of c-Myc significantly enhanced intra- and extracellular levels of TSP-1 after ammonia treatment in cultured astrocytes. Further, exposure of cultured neurons (24 h) to CM from ammonia-treated astrocytes in which c-Myc was silenced or inhibited by 10058-F4, caused a reversal of the synaptophysin loss. A reduction in TSP-1 and neuronal synaptophysin were also detected in an in vivo rat model of CHE. Altogether, these findings strongly suggest that an ammonia-induced reduction in TSP-1, and possibly other factors in astrocytes (see below), results in a decline in synaptic protein levels, which likely contributes to the pathogenesis of CHE.

TSP-1, also known as THBS1 or THP1 protein, is a member of the thrombospondin family that in humans is encoded by the THBS1 gene. This protein can bind to fibrinogen, fibronectin, laminin, type V collagen and integrins alpha-V/beta-1, and thereby initiate cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions (Li et al. 2002). TSP-1 expression was identified in postnatal and young adult animal brains (Lu and Kipnis 2010; Yonezawa et al. 2010), as well as in normal human cortical astrocytes (Asch et al. 1986). Further, cultured astrocytes are known to synthesize and secrete TSP-1 (Christopherson et al. 2005; Tran and Neary 2006; Yonezawa et al. 2010). Under normal conditions, TSP-1 causes an increase in the total number of synapses (Christopherson et al., 2005; Eroglu et al., 2009), as well as accelerates synaptogenesis (Xu et al., 2010). Astrocyte-derived thrombospondin-1 was also shown to mediate the development of presynaptic plasticity in vitro (Crawford et al. 2012). Conversely, defective astrocytic TSP-1 release is known to be associated with neuronal dysfunction (Garcia et al. 2010).

Yu et al. (2008) demonstrated that retinal ganglion cell (RGC) survival and neurite outgrowth were improved when co-cultured with bone marrow stromal cells (which are known to release TSP-1), a process mediated by the up-regulation of synaptophysin. On the other hand, decreasing TSP-1 expression by siRNA silencing led to a reduction in neurite outgrowth and a decrease in the expression of synaptophysin in RGCs (Yu et al. 2008). In comparable studies, Rama Rao et al., 2013 showed that exposure of cultured astrocytes to β-amyloid peptide significantly reduced extracellular TSP-1, and that CM from these β-amyloid peptide-treated astrocytes when added to cultured neurons led to a decrease in synaptophysin protein levels.

In the present study, we observed a significant decrease in both TSP-1 synthesis and release when cultured astrocytes were exposed to a pathophysiologically relevant concentration of ammonia (1 mM), and that inhibition of c-Myc reversed the ammonia-induced reduction in TSP-1 (see below), suggesting the involvement of a transcriptional regulatory mechanism underlying the effect of ammonia on TSP-1. However, as noted just above, β-amyloid peptide reduced only the extracelluar, but not intracellular TSP-1 levels, suggesting that the mode of action of ammonia on astrocytic TSP-1 content is different from the effect of β-amyloid peptide. We also found that exposure of cultured neurons to CM from ammonia-treated astrocytes led to a decrease in synaptophysin protein levels, while the addition of recombinant TSP-1 diminished this effect. These findings indicate that a decrease in both intra- and extracellular TSP-1 contributes to the reduction of neuronal synaptophysin observed in CHE. It is, however, possible that a diminution in astrocytic factors other than TSP-1 (e.g., SPARC, glypicans, nerve growth factor, basic fibroblast growth factor, as well as cholesterol) may also have contributed to the reduction in synaptophysin levels following ammonia treatment. In this regard, it is noteworthy that we found a reduction in hevin and TGF-β1 in ammonia-treated astrocytes, which may also have contributed to the reduction in TSP-1.

TSP-1 protein levels were not changed at day 10 after 0.5 mM ammonia treatment, although a significant decline in TSP-1 mRNA level was detected at that time (Figure 2). Similar findings were also observed with 0.5 and 1 mM ammonia at day 5 after treatment (Suppl. Figure 2 B and C). The reason for the delayed decrease in TSP-1 protein compared to mRNA may be due to a slow turnover rate of TSP-1 protein. While the effect of a pathophysiologically relevant concentration of ammonia (1 mM) on TSP-1 levels seems to be due to defective synthesis, the effect of 0.5 mM ammonia on extracellular TSP-1 level is likely due to an impairment in release or enhanced extracellular degradation.

While the mechanism by which ammonia reduces the synthesis and secretion of TSP-1 in CHE is not known, it is likely that oxidative/nitrative stress (ONS), and the activation of NF-κB are involved (Chen et al. 2011; De Stefano et al. 2009; Tan et al. 2009). Markers of ONS have been identified in animal models of CHE, and in humans with CHE (Watnick et al. 2003). Additionally, activation of NF-κB was identified in ammonia-treated cultured astrocytes (Schliess et al. 2002; Sinke et al. 2008; Jayakumar et al. 2011). In the present study, the decrease in intra- and extracellular TSP-1 levels when astrocytes were treated with ammonia were inhibited by antioxidants, as well as by an NF-κB inhibitor, implicating ONS and NF-κB in the reduction of astrocytic TSP-1 by ammonia. In agreement with these findings, it was shown that exposure of astrocyte cultures to cobalt chloride (an inducer of reactive oxygen species) inhibited TSP-1 mRNA expression (Chen et al. 2011), while the NF-κB inhibitor SN50 reduced the TSP-1 downregulation in cultured human retinal glial cells following viral infection (Cinatl et al. 2000).

c-Myc is a transcription factor that is expressed in astrocytes in vitro and in vivo (Liu et al. 2006; Saljo et al. 2002). Overexpression of c-Myc protein was shown to cause a decrease in TSP-1 protein level by exerting a repressor effect on TSP-1 mRNA (Watnick et al. 2003). Our study also identified an increase in c-Myc protein level in ammonia-treated astrocytes (1.0 mM for 10 d), while the pharmacological inhibition of c-Myc, or silencing c-Myc by siRNA prevented the reduction in TSP-1 levels by ammonia (Figures 5 and 6). In addition to c-Myc inhibition, antioxidants and NF-κB inhibitors also prevented the reduction in TSP-1 levels by ammonia (see above), suggesting that ONS and NF-κB also contribute to the regulation of TSP-1 in CHE.

The activation of ONS, NF-κB and c-Myc were identified in astrocytes at similar time points (8–10 d) after ammonia-treatment. Since all of these factors appear to have contributed to the reduction in TSP-1 synthesis and release, it is possible that these factors acted independently to reduce TSP-1 synthesis and release. However, interaction among these factors may also have occurred. For example, ONS is known to activate NF-κB (Bowie and O’Neill, 2000); NF-κB is known to stimulate c-Myc activation (La Rosa et al., 1994; Ji et al., 1994), and ONS is known to increase c-Myc expression (Höcker et al., 1998; Joseph et al., 2001). Nevertheless, the precise mechanisms by which these factors ultimately lead to a reduction in TSP-1 levels in ammonia-treated astrocytes, remains to be determined.

It should also be noted that ONS and NF-κB can also inhibit TGF-β (Choi et al., 2013; Bitzer et al., 2000), which is known to stimulate the production of TSP-1 in astrocytes (Cambier et al., 2005; Yonezawa et al., 2010). Further, TGF-β has been shown to reduce c-Myc expression (Pietenpol et al., 1990; Warner et al., 1999). Since we found decreased levels of TGF-β in ammonia-treated astrocytes, it is possible that the ONS- and NF-κB-mediated decrease in TGF-β may have enhanced c-Myc expression resulting in reduced levels of TSP-1.

In addition to ONS, NF-κB, and c-Myc, a number of other signaling factors, including p53, specificity protein 1 (Sp1), activating transcription factor-1 (ATF-1), activator protein 1 (AP-1), Forkhead box O (FoxO1), E2F transcription factor 1 (E2F1), Runx2/3, as well as transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), have been implicated in the mechanism of TSP-1 regulation in other conditions (Janz et al. 2000; Ji et al. 2010; Li and Rossman 2001; Roudier et al. 2013; Salnikow et al. 1997; Shi et al. 2013). Whether these factors are also involved in the ammonia-induced reduction of TSP-1 in astrocytes, and the associated loss of synaptophysin, in not known.

Synaptophysin is an abundant integral membrane protein of pre-synaptic vesicles involved in the regulation of neurotransmitter release and synaptic plasticity (Alder et al. 1995; Janz et al. 1999). It also participates in the biogenesis and recycling of synaptic vesicles, as mice lacking synaptophysin exhibit behavioral alterations and learning deficits (Schmitt et al. 2009). Additionally, the loss of synaptophysin in the hippocampus was shown to correlate with a cognitive decline in patients with Alzheimer’s disease (Sze 1997), is in keeping with the involvement of synaptophysin in the maintenance of synaptic integrity. Our study likewise identified a decrease in synaptophysin level when cultured neurons were exposed to CM derived from ammonia-treated astrocytes. We similarly found decreased synaptophysin levels in brains from rats with experimental CHE. Further, PSD95, a post-synaptic density protein and synaptotagmin-1, a Ca2+ sensor in the plasma membrane of pre-synaptic axon terminals which is involved in the maintenance of synaptic integrity, were similarly negatively affected by ammonia.

It should be emphasized that a reduction in synaptic proteins in CHE was not due to neuronal loss, as such loss is not a feature of CHE (Norenberg 1981). Moreover, no neuronal loss or reactive glial changes were observed in these rats. Instead, the presence of Alzheimer-type II astrocytes was the major neuropathological abnormality observed in this condition (Suppl. Figure 1), consistent with the concept that defective astrocytes are a major factor in the loss of synaptic integrity in CHE.

The means by which a reduction in TSP-1 decreases synaptic protein levels in CHE is not known. Studies have shown that TSP-1 binds and activates integrin alpha-V/beta-1, leading to the stability of synaptophysin (DeFreitas et al. 1995), and that a defect in this process may lead to a reduction in synaptophysin levels, with or without synaptic loss. Whether integrins alpha-V/beta-1 or other integrin receptors are involved in the reduction in synaptic proteins in CHE remains to be established.

In conclusion, a significant reduction in TSP-1 protein level was observed in ammonia-treated astrocyte cultures. Such reduction was associated with a decrease in neuronal synaptic proteins when conditioned media from ammonia-treated astrocytes was added to cultured neurons. We further observed a significant reduction in astrocytic TSP-1 and in neuronal synaptophysin protein in a rat model of CHE. Our findings suggest that dysfunctional astrocytes (a glyopathy) resulting from ammonia treatment negatively impacts neuronal synaptic integrity, which may contribute to the neurological abnormalities known to occur in patients with CHE. Targeting astrocytic TSP-1 may provide a novel therapeutic strategy for the neurological abnormalities associated with CHE.

Supplementary Material

TABLE.

Blood and brain ammonia levels of rats treated with thioacetamide (TAA)

| Control | TAA | |

|---|---|---|

| Blood ammonia (µmol/L) | 191.6 ± 11.7 | 611.2 ± 32.1* |

| Brain ammonia (mM) | 0.34 ± 0.07 | 0.96 ± 0.16* |

Control n = 5; TAA n = 5. Blood and brain ammonia levels were determined 24 h after the last injection of TAA (100 mg/kg b.wt.).

p<0.05 vs. control.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Merit Review from the Department of Veterans Affairs and by a National Institutes of Health grant DK063311. KMC was supported by an NIH-NIAMS post-doctoral fellowship (7F32AR062990–02).

The authors thank Alina Fernandez-Revuelta for the preparation of cell cultures.

Abbreviations

- CHE

chronic hepatic encephalopathy

- CM

conditioned media

- GFAP

glial fibrillary acidic protein

- NH4Cl

ammonium chloride (ammonia)

- TAA

thioacetamide

- TSP-1

thrombospondin-1

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Abbott NJ, Rönnbäck L, Hansson E. Astrocyte-endothelial interactions at the blood-brain barrier. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2006;7:41–53. doi: 10.1038/nrn1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alder J, Kanki H, Valtorta F, Greengard P, Poo MM. Overexpression of synaptophysin enhances neurotransmitter secretion at Xenopus neuromuscular synapses. J. Neurosci. 1995;15:511–519. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-01-00511.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ampuero J, Ranchal I, Nuñez D, Díaz-Herrero Mdel M, Maraver M, del Campo JA, Rojas Á, Camacho I, Figueruela B, Bautista JD, Romero-Gómez M. Metformin inhibits glutaminase activity and protects against hepatic encephalopathy. PLoS One. 2012;7:e49279. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asch AS, Leung LL, Shapiro J, Nachman RL. Human brain glial cells synthesize thrombospondin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1986;83:2904–2908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.9.2904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bélanger M, Magistretti PJ. The role of astroglia in neuroprotection. Dialogues. Clin. Neurosci. 2009;11:281–295. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2009.11.3/mbelanger. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bismuth M, Funakoshi N, Cadranel JF, Blanc P. Hepatic encephalopathy: from pathophysiology to therapeutic management. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2011;23:8–22. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283417567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie A, O’Neill LA. Oxidative stress and nuclear factorkappaB activation: a reassessment of the evidence in the light of recent discoveries. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2000;59:13–23. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00296-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buée L, Hof PR, Roberts DD, Delacourte A, Morrison JH, Fillit HM. Immunohistochemical identification of thrombospondin in normal human brain and in Alzheimer's disease. Am. J. Pathol. 1992;141:783–788. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbonero-Aguilar P, Diaz-Herrero Mdel M, Cremades O, Romero-Gómez M, Bautista J. Brain biomolecules oxidation in portacaval shunted rats. Liver Int. 2011;31:964–969. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauli O, Rodrigo R, Llansola M, Montoliu C, Monfort P, Piedrafita B, El Mlili N, Boix J, Agustí A, Felipo V. Glutamatergic and gabaergic neurotransmission and neuronal circuits in hepatic encephalopathy. Metab. Brain Dis. 2009;24:69–80. doi: 10.1007/s11011-008-9115-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Zhan YJ, Yang CS, Tzeng SF. Oxidative stress-induced attenuation of thrombospondin-1 expression in primary rat astrocytes. J. Cell. Biochem. 2011;112:59–70. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopherson KS, Ullian EM, Stokes CC, Mullowney CE, Hell JW, Agah A, Lawler J, Mosher DF, Bornstein P, Barres BA. Thrombospondins are astrocyte-secreted proteins that promote CNS synaptogenesis. Cell. 2005;120:421–433. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cinatl J, Jr, Bittoova M, Margraf S, Vogel JU, Cinatl J, Preiser W, Doerr HW. Cytomegalovirus infection decreases expression of thrombospondin-1 and −2 in cultured human retinal glial cells: effects of antiviral agents. J. Infect. Dis. 2000;182:643–651. doi: 10.1086/315779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper AJ, McDonald JM, Gelbard AS, Gledhill RF, Duffy TE. The metabolic fate of 13N–labeled ammonia in rat brain. J. Biol. Chem. 1979;254:4982–4992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford DC, Jiang X, Taylor A, Mennerick S. Astrocyte-derived thrombospondins mediate the development of hippocampal presynaptic plasticity in vitro. J. Neurosci. 2012;32:13100–13110. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2604-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Stefano D, Nicolaus G, Maiuri MC, Cipolletta D, Galluzzi L, Cinelli MP, Tajana G, Iuvone T, Carnuccio R. NF-kappaB blockade upregulates Bax, TSP-1, and TSP-2 expression in rat granulation tissue. J. Mol. Med. 2009;87:481–492. doi: 10.1007/s00109-009-0443-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFreitas MF, Yoshida CK, Frazier WA, Mendrick DL, Kypta RM, Reichardt LF. Identification of integrin alpha 3 beta 1 as a neuronal thrombospondin receptor mediating neurite outgrowth. Neuron. 1995;15:333–343. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90038-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dejong CH, Deutz NE, Soeters PB. Cerebral cortex ammonia and glutamine metabolism in two rat models of chronic liver insufficiency-induced hyperammonemia: influence of pair-feeding. J. Neurochem. 1993;60:1047–1057. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb03253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducis I, Norenberg LO, Norenberg MD. The benzodiazepine receptor in cultured astrocytes from genetically epilepsy-prone rats. Brain. Res. 1990;531:318–321. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90793-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia O, Torres M, Helguera P, Coskun P, Busciglio J. A role for thrombospondin-1 deficits in astrocyte-mediated spine and synaptic pathology in Down's syndrome. PLoS One. 2010;5:e14200. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Höcker M, Rosenberg I, Xavier R, Henihan RJ, Wiedenmann B, Rosewicz S, Podolsky DK, Wang TC. Oxidative stress activates the human histidine decarboxylase promoter in AGS gastric cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:23046–23054. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.36.23046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janz A, Sevignani C, Kenyon K, Ngo CV, Thomas-Tikhonenko A. Activation of the myc oncoprotein leads to increased turnover of thrombospondin-1 mRNA. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 2000;28:2268–2275. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.11.2268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janz R, Südhof TC, Hammer RE, Unni V, Siegelbaum SA, Bolshakov VY. Essential roles in synaptic plasticity for synaptogyrin I and synaptophysin I. Neuron. 1999;24:687–700. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81122-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayakumar AR, Rao KV, Murthy ChR, Norenberg MD. Glutamine in the mechanism of ammonia-induced astrocyte swelling. Neurochem. Int. 2006;48:623–628. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2005.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayakumar AR, Bethea JR, Tong XY, Gomez J, Norenberg MD. NF-κB in the mechanism of brain edema in acute liver failure: studies in transgenic mice. Neurobiol. Dis. 2011;41:498–507. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayakumar AR, Norenberg MD. In: Oxidative stress in hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatic encephalopathy, Clinical Gastroenterology. Mullen KD, Prakash RK, editors. Springer; 2012. pp. 47–70. [Google Scholar]

- Jayakumar AR, Tong XY, Curtis KM, Ruiz-Cordero R, Abreu MT, Norenberg MD. Increased toll-like receptor 4 in cerebral endothelial cells contributes to the astrocyte swelling and brain edema in acute hepatic encephalopathy. J. Neurochem. 2014;128:890–903. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji L, Arcinas M, Boxer LM. NF-kappa B sites function as positive regulators of expression of the translocated c-myc allele in Burkitt's lymphoma. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1994;14:7967–7974. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.12.7967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji W, Zhang W, Xiao W. E2F-1 directly regulates thrombospondin 1 expression. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13442. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph P, Muchnok TK, Klishis ML, Roberts JR, Antonini JM, Whong WZ, Ong T. Cadmium-induced cell transformation and tumorigenesis are associated with transcriptional activation of c-fos, c-jun, and c-myc proto-oncogenes: role of cellular calcium and reactive oxygen species. Toxicol Sci. 2001;61:295–303. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/61.2.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juurlink BH, Hertz L. Plasticity of astrocytes in primary cultures: an experimental tool and a reason for methodological caution. Dev Neurosci. 1985;7:263–277. doi: 10.1159/000112295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura T, Budka H. Glial fibrillary acidic protein and S-100 protein in human hepatic encephalopathy: immunocytochemical demonstration of dissociation of two glia-associated proteins. Acta Neuropathol. 1986;70:17–21. doi: 10.1007/BF00689509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kretzschmar HA, DeArmond SJ, Forno LS. Measurement of GFAP in hepatic encephalopathy by ELISA and transblots. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 1985;44:459–471. doi: 10.1097/00005072-198509000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucukdereli H, Allen NJ, Lee AT, Feng A, Ozlu MI, Conatser LM, Chakraborty C, Workman G, Weaver M, Sage EH, Barres BA, Eroglu C. Control of excitatory CNS synaptogenesis by astrocyte-secreted proteins Hevin and SPARC. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2011;108:E440–E449. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104977108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange SC, Bak LK, Waagepetersen HS, Schousboe A, Norenberg MD. Primary Cultures of Astrocytes: Their Value in Understanding Astrocytes in Health and Disease. Neurochem Res. 2012;37:2569–2588. doi: 10.1007/s11064-012-0868-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Rosa FA, Pierce JW, Sonenshein GE. Differential regulation of the c-myc oncogene promoter by the NF-kappa B rel family of transcription factors. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:1039–1044. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.2.1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee WM. Acute liver failure. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care. Med. 2012;33:36–45. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1301733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Rossman TG. Genes upregulated in lead-resistant glioma cells reveal possible targets for lead-induced developmental neurotoxicity. Toxicol Sci. 2001;64:90–99. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/64.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Calzada MJ, Sipes JM, Cashel JA, Krutzsch HC, Annis DS, Mosher DF, Roberts DD. Interactions of thrombospondins with alpha4beta1 integrin and CD47 differentially modulate T cell behavior. J. Cell. Biol. 2002;157:509–519. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200109098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liauw J, Hoang S, Choi M, Eroglu C, Choi M, Sun GH, Percy M, Wildman-Tobriner B, Bliss T, Guzman RG, Barres BA, Steinberg GK. Thrombospondins 1 and 2 are necessary for synaptic plasticity and functional recovery after stroke. J. Cereb. Blood. Flow. Metab. 2008;28:1722–1732. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin TN, Kim GM, Chen JJ, Cheung WM, He YY, Hsu CY. Differential regulation of thrombospondin-1 and thrombospondin-2 after focal cerebral ischemia/reperfusion. Stroke. 2003;34:177–186. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000047100.84604.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Narasimhan P, Lee YS, Song YS, Endo H, Yu F, Chan PH. Mild hypoxia promotes survival and proliferation of SOD2-deficient astrocytes via c-Myc activation. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:4329–4337. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0382-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llansola M, Montoliu C, Cauli O, Hernández-Rabaza V, Agustí A, Cabrera-Pastor A, Giménez-Garzó C, González-Usano A, Felipo V. Chronic hyperammonemia, glutamatergic neurotransmission and neurological alterations. Metab. Brain. Dis. 2012;28:151–154. doi: 10.1007/s11011-012-9337-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Q, Hong W. Bcl2 enhances c-Myc-mediated MMP-2 expression of vascular smooth muscle cells. Cell Signal. 2009;21:1054–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z, Kipnis J. Thrombospondin 1-a key astrocyte-derived neurogenic factor. FASEB J. 2010;24:1925–1934. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-150573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masliah E, Ge N, Morey M, DeTeresa R, Terry RD, Wiley CA. Cortical dendritic pathology in human immunodeficiency virus encephalitis. Lab Invest. 1992;66:285–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGillicuddy FC, O'Toole D, Hickey JA, Gallagher WM, Dawson KA, Keenan AK. TGF-beta1-induced thrombospondin-1 expression through the p38 MAPK pathway is abolished by fluvastatin in human coronary artery smooth muscle cells. Vascul Pharmacol. 2006;44:469–475. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimura Y, Ihn H, Jinnin M, Asano Y, Yamane K, Tamaki K. Constitutive thrombospondin-1 overexpression contributes to autocrine transforming growth factor-beta signaling in cultured scleroderma fibroblasts. Am. J. Pathol. 2005;166:1451–1463. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)62362-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JD, Borasio GD. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet. 2007;369:2031–2041. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60944-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen KD, Prakash RK. New perspectives in hepatic encephalopathy. Clin. Liver. Dis. 2012;16:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norenberg MD. Distribution of glutamine synthetase in the rat central nervous system. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1979;27:756–762. doi: 10.1177/27.3.39099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norenberg MD. In: The astrocyte in liver disease. Advances in Cellular Neurobiology. Fedoroff S, Hertz L, editors. New York: Academic Press; 1981. pp. 303–352. [Google Scholar]

- Norenberg MD. The role of astrocytes in hepatic encephalopathy. Neurochem Pathol. 1987;6:13–33. doi: 10.1007/BF02833599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norenberg MD. In: Astrocytes. Fedoroff S, Vernadakis A, editors. Vol. 3 Acad Press; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Norenberg MD, Itzhak Y, Bender AS, Baker L, Aguila-Mansilla HN, Zhou BG, Isaacks R. In: Ammonia and astrocyte function. Liver and Nervous System. Häussinger D, Jungermann K, editors. Dordrecht, Kluwer Acad Pub; 1998. pp. 276–293. [Google Scholar]

- Norenberg MD, Neary JT, Bender AS, Dombro RS. Hepatic encephalopathy: A disorder in glial–neuronal communication. In: Yu ACH, Hertz L, Norenberg MD, Sykova E, Waxman SG, editors. Neuronal–Astrocytic Interactions. Implications for Normal and Pathological CNS function. Vol. 94. Progress in Brain Research, Elsevier; Amsterdam: 1992. pp. 261–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norenberg MD, Rama Rao KV, Jayakumar AR. Signaling factors in the mechanism of ammonia neurotoxicity. Metab. Brain. Dis. 2009;24:103–117. doi: 10.1007/s11011-008-9113-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto M, Ono M, Uchiumi T, Ueno H, Kohno K, Sugimachi K, Kuwano M. Up-regulation of thrombospondin-1 gene by epidermal growth factor and transforming growth factor beta in human cancer cells--transcriptional activation and messenger RNA stabilization. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2002;1574:24–34. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(01)00345-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel D, McPhail MJ, Cobbold JF, Taylor-Robinson SD. Hepatic encephalopathy. Br J. Hosp. Med. 2012;73:79–85. doi: 10.12968/hmed.2012.73.2.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietenpol JA, Holt JT, Stein RW, Moses HL. Transforming growth factor beta 1 suppression of c-myc gene transcription: role in inhibition of keratinocyte proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:3758–3762. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.10.3758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy PH, Mani G, Park BS, Jacques J, Murdoch G, Whetsell W, Jr, Kaye J, Manczak M. Differential loss of synaptic proteins in Alzheimer's disease: implications for synaptic dysfunction. J. Alzheimers. Dis. 2005;7:103–117. doi: 10.3233/jad-2005-7203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rick FG, Abi-Chaker A, Szalontay L, Perez R, Jaszberenyi M, Jayakumar AR, Shamaladevi N, Szepeshazi K, Vidaurre I, Halmos G, Krishan A, Block NL, Schally AV. Shrinkage of experimental benign prostatic hyperplasia and reduction of prostatic cell volume by a gastrin-releasing peptide antagonist. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;12:2617–2622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222355110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roudier E, Milkiewicz M, Birot O, Slopack D, Montelius A, Gustafsson T, Paik JH, Depinho RA, Casale GP, Pipinos II, Haas TL. Endothelial FoxO1 is an intrinsic regulator of thrombospondin 1 expression that restrains angiogenesis in ischemic muscle. Angiogenesis. 2013;16:759–772. doi: 10.1007/s10456-013-9353-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saljo A, Bao F, Shi J, Hamberger A, Hansson HA, Haglid KG. Expression of c-Fos and c-Myc and deposition of beta-APP in neurons in the adult rat brain as a result of exposure to short-lasting impulse noise. J. Neurotrauma. 2002;19:379–385. doi: 10.1089/089771502753594945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salnikow K, Wang S, Costa M. Induction of activating transcription factor 1 by nickel and its role as a negative regulator of thrombospondin I gene expression. Cancer Res. 1997;57:5060–5066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki S, Maruyama S. Decreased synaptophysin immunoreactivity of the anterior horns in motor neuron disease. Acta Neuropathol. 1994;87:125–128. doi: 10.1007/BF00296180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schliess F, Görg B, Fischer R, Desjardins P, Bidmon HJ, Herrmann A, Butterworth RF, Zilles K, Häussinger D. Ammonia induces MK-801-sensitive nitration and phosphorylation of protein tyrosine residues in rat astrocytes. FASEB J. 2002;16:739–741. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0862fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmandra TC, Bauer H, Petrowsky H, Herrmann G, Encke A, Hanisch E. Effects of fibrin glue occlusion of the hepatobiliary tract on thioacetamide-induced liver failure. Am. J. Surg. 2001;182:58–63. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(01)00659-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt U, Tanimoto N, Seeliger M, Schaeffel F, Leube RE. Detection of behavioral alterations and learning deficits in mice lacking synaptophysin. Neuroscience. 2009;162:234–243. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schousboe A, Meier E, Drejer J, Hertz L. In: Preparation of primary cultures of mouse (rat) cerebellar granule cells. A Dissection and Tissue Culture Manual for The Nervous System. Shahar A, de Vellis J, Vernadakis A, Haber S, editors. New York: Alan R. Liss; 1989. pp. 203–206. [Google Scholar]

- Seifert G, Schilling K, Steinhäuser C. Astrocyte dysfunction in neurological disorders: a molecular perspective. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2006;7:194–206. doi: 10.1038/nrn1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shawcross DL, Wendon JA. The neurological manifestations of acute liver failure. Neurochem Int. 2012;60:662–671. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi X, Deepak V, Wang L, Ba X, Komori T, Zeng X, Liu W. Thrombospondin-1 is a putative target gene of runx2 and runx3. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013;14:14321–14332. doi: 10.3390/ijms140714321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S, Trigun SK. Activation of neuronal nitric oxide synthase in cerebellum of chronic hepatic encephalopathy rats is associated with up-regulation of NADPH-producing pathway. Cerebellum. 2010;9:384–397. doi: 10.1007/s12311-010-0172-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinke AP, Jayakumar AR, Panickar KS, Moriyama M, Reddy PV, Norenberg MD. NFkappaB in the mechanism of ammonia-induced astrocyte swelling in culture. J. Neurochem. 2008;106:2302–2311. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05549.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel RA, DeArmond SJ, Forno LS, Eng LF. Glial fibrillary acidic protein in hepatic encephalopathy. An immunohistochemical study. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 1981;40:625–632. doi: 10.1097/00005072-198111000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sze CI. Loss of the presynaptic vesicle protein synaptophysin in hippocampus correlates with cognitive decline in Alzheimer disease. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 1997;56:933–944. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199708000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan BK, Adya R, Chen J, Farhatullah S, Heutling D, Mitchell D, Lehnert H, Randeva HS. Metformin decreases angiogenesis via NF-kappaB and Erk1/2/Erk5 pathways by increasing the antiangiogenic thrombospondin-1. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;83:566–574. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka S, Saito M, Morimatsu M, Ohama E. Immunohistochemical studies of the PrP(CJD) deposition in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Neuropathology. 2000;20:124–133. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1789.2000.00285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran MD, Neary JT. Purinergic signaling induces thrombospondin-1 expression in astrocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:9321–9326. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603146103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakim-Fleming J. Hepatic encephalopathy: Suspect it early in patients with cirrhosis. Clev. Clin. J. Med. 2011;78:597–605. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.78a10117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang DD, Bordey A. The astrocyte odyssey. Prog Neurobiol. 2008;86:342–367. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2008.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner BJ, Blain SW, Seoane J, Massagué J. Myc downregulation by transforming growth factor beta required for activation of the p15(Ink4b) G(1) arrest pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5913–5922. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.9.5913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watnick RS, Cheng YN, Rangarajan A, Ince TA, Weinberg RA. Ras modulates Myc activity to repress thrombospondin-1 expression and increase tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:219–231. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00030-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonezawa T, Hattori S, Inagaki J, Kurosaki M, Takigawa T, Hirohata S, Miyoshi T, Ninomiya Y. Type IV collagen induces expression of thrombospondin-1 that is mediated by integrin alpha1beta1 in astrocytes. Glia. 2010;58:755–767. doi: 10.1002/glia.20959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu K, Ge J, Summers JB, Li F, Liu X, Ma P, Kaminski J, Zhuang J. TSP-1 secreted by bone marrow stromal cells contributes to retinal ganglion cell neurite outgrowth and survival. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2470. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.