Abstract

Background

Obesity is a growing global concern with strong associations with cardiovascular disease, cancer and type-2 diabetes. Although various genome-wide association studies have identified more than 40 genes associated with obesity, these genes cannot fully explain the heritability of obesity, suggesting there may be other contributing factors, including epigenetic effects.

Results

We performed genome wide DNA methylation profiling comparing normal-weight and obese 9–13 year old children to investigate possible epigenetic changes correlated with obesity. Of note, obese children had significantly lower methylation levels at a CpG site located near coronin 7 (CORO7), which encodes a tryptophan-aspartic acid dipeptide (WD)-repeat containing protein most likely involved in Golgi complex morphology and function. Anatomical profiling of coronin 7 (Coro7) mRNA expression in mice revealed that it is highly expressed in appetite and energy balance regulating regions, including the hypothalamus, striatum and locus coeruleus, the main noradrenergic brain site. Interestingly, we found that food deprivation in mice downregulates hypothalamic Coro7 mRNA levels, and injecting ethanol, an appetite stimulant, increased the number of Coro7 expressing cells in the locus coeruleus. Finally, by employing the genetically-tractable Drosophila melanogaster model we were able to demonstrate an evolutionarily conserved metabolic function for the CORO7 homologue pod1. Knocking down the pod1 in the Drosophila adult nervous system increased their resistance to starvation. Furthermore, feeding flies a high-calorie diet significantly increased pod1 expression.

Conclusion

We conclude that coronin 7 is involved in the regulation of energy homeostasis and this role stems, to some degree, from the effect on feeding for calories and reward.

Keywords: Coronin 7, Obesity, Homeostatic control, Gene expression

Background

Obesity is a global health problem strongly associated with decreased life expectancy due to high risk for cardiovascular diseases, various types of cancer, type-2 diabetes mellitus, and depression [1,2]. Obesity has a strong heritable component that could explain as much as 40-70% of non-syndromic cases [3-5]. Although genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified more than 40 genetic variants associated with obesity and fat distribution [4], the individual contribution of these genes is small and thus cannot fully explain the heritability of obesity. This suggests that there may be other contributing factors, including epigenetic effects [6].

The coronin family encodes for actin-binding proteins that are divided into two evolutionarily conserved tryptophan-aspartic acid dipeptide (WD)-40 repeat containing groups, short and long, based on their domain composition and structure [7]. This family has seven vertebrate classes where the human members are coronin 1A, 1B, 1C, 2A, 2B, 6 and 7. Distinct from other family members, coronin 7, including its homologues in C. elegans and D. melanogaster, has two duplicate WD domains in tandem repeats [8]. Furthermore, unlike other coronin proteins, mammalian coronin 7 may not be an actin-binding protein but instead locates to the Golgi complex and is thought to be involved in Golgi complex maintenance and morphology, as well as in regulating protein trafficking in an anterograde direction [8-10]. Yet, similar to other coronin-like proteins the Drosophila CORO7 homologue Pod1 localizes to the tips of growing axons, where it crosslinks to both actin and microtubules. Overexpression of Pod1 greatly remodels the cytoskeleton to promote dynamic neurite-like actin-dependent projections [11].

Currently, only one study has investigated Coro7 distribution in the mouse brain, where it was shown to be expressed in the hippocampus and cortex throughout development, however, no other brain areas were investigated in this study [8]. Moreover, a preliminary expression profile of coronin 7, obtained using Western blot analysis of embryonic murine tissues, suggested it was ubiquitously expressed in peripheral organs. Nevertheless, even after these studies it is still unclear which cell type(s) express Coro7 in vivo. In this study, we performed genome wide methylation analysis demonstrating that CORO7 is differentially methylated in obese compared to normal-weight children. Furthermore, we observed that the number of Coro7 expressing neurons within the locus coeruleus increases after ethanol injection, a treatment known to potentiate appetite in rodents [12,13]. Expressional changes of Coro7 under different dietary compositions were analyzed to explore any possible functional importance. We provide a detailed characterization of mouse Coro7 distribution, as well as detailed expression in the mouse brain. Interestingly, knocking down the Drosophila CORO7 homologue pod1 in the adult nervous system induced a starvation-resistance phenotype. Finally, we demonstrate that, similar to murine Coro7, Drosophila pod1 expression is regulated by dietary macronutrient content.

Methods

Epigenetics

Children’s cohort

Data on 9 to 13 year old children were derived from the Healthy Growth Study. More details on this study are provided elsewhere [14].

For the purpose of the current analysis, a subsample of 24 obese and 23 normal-weight preadolescent girls as well as 11 obese and 11 normal-weight preadolescent boys (Tables 1 and 2) was selected. This subsample was initially used to investigate the effect of polymorphism in the FTO gene on genome-wide DNA methylation patterns [15].

Table 1.

Top 15 differently methylated sites in weight category and the STK33 rs4929949 polymorphism; Weight category

| Gene | Entrez gene ID | Genomic position of the probe/island (hg19) | HIL class | Genomic location of the closest TSS (hg19) | Coefficient | Raw p-value | Adjusted p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CKAP2L | 150468 | chr2:113521873 | HC | 113522253 | 0,159 | 8,46E-06 | 8,85E-02 |

| DCHS1 | 8642 | chr11:6676514 | HC | 6677073 | −0,221 | 3,92E-05 | 2,05E-01 |

| ZNF35 | 7584 | chr3_IC:44689963-44690779 | IC | 44690232 | −0,14 | 7,16E-05 | 2,22E-01 |

| HAP1 | 9001 | chr17:39890959 | HC | 39890897 | −0,159 | 8,47E-05 | 2,22E-01 |

| PIN1 | 5300 | chr19:9945603 | HC | 9945882 | 0,152 | 0,000108 | 0,226 |

| SERF2 | 10169 | HCshore:44083868–44085029; ICshore:44084026-44085439 | HC | 44084574 | 0,128 | 0,00015 | 0,26 |

| CERCAM | 51148 | chr9_HCshore:131182042–131183333; chr9_ICshore:131181735-131183621 | HC | 131182465 | −0,157 | 0,000189 | 0,26 |

| TEX10 | 54881 | chr9:103115131 | HC | 103115258 | −0,19 | 0,000199 | 0,26 |

| CORO7-PAM16 | 100529144 | chr16:4466649 | HC | 4466961 | −0,137 | 0,000255 | 0,272 |

| NME1-NME2 | 654364 | chr17_HCshore:49230603–49231546; chr17_ICshore:49230561-49231528 | HC | 49230896 | −0,109 | 0,00026 | 0,272 |

| ARHGDIB | 397 | chr12:15114393 | IC | 15114561 | −0,191 | 0,000314 | 0,298 |

| KLK10 | 5655 | chr19_HCshore:51520036–51521297; chr19_ICshore:51519915-51521326 | HC | 51522953 | −0,142 | 0,000439 | 0,383 |

| ZNF215 | 7762 | chr11:6947572 | HC | 6947653 | −0,164 | 0,000729 | 0,549 |

| HEATR6 | 63897 | chr17:58156231 | HC | 58156291 | 0,132 | 0,000754 | 0,549 |

| SLC22A18 | 5002 | .;chr11_IC:2923161-2923957 | IC | 2923511 | −0,134 | 0,000965 | 0,549 |

Abbreviations: high-density CpG island (HC), intermediate-density CpG island (IC), region of intermediate-density CpG island that borders HCs (ICshore).

Table 2.

Top 15 differently methylated sites in weight category and the STK33 rs4929949 polymorphism; STK33 category

| Gene | Entrez gene ID | Genomic position of the probe/island (hg19) | HIL class | Genomic location of the closest TSS (hg19) | Coefficient | Raw p-value | Adjusted p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| REM1 | 28954 | chr20_IC:30062552-30063794 | IC | 30063104 | −0,0931 | 5,76E-06 | 0,0324 |

| TERT | 7015 | chr5_HCshore:1294078–1296099; chr5_ICshore:1292899-1296102 | HC | 1295161 | −0,149 | 1,03E-05 | 0,0324 |

| DRD5 | 1816 | chr4:9782881 | ICshore | 9783257 | −0,16 | 1,13E-05 | 0,0324 |

| TRPC3 | 7222 | chr4:122853965 | HC | 122854196 | −0,25 | 1,72E-05 | 0,0324 |

| FOXD1 | 2297 | chr5:72744904 | ICshore | 72744351 | −0,115 | 1,84E-05 | 0,0324 |

| ESPNL | 339768 | chr2:239008986 | IC | 239008950 | −0,158 | 1,86E-05 | 0,0324 |

| ZFYVE9 | 9372 | chr1:52608558 | HC | 52608045 | −0,133 | 2,37E-05 | 0,0354 |

| NPY4R | 5540 | chr10:47083233 | IC | 47083533 | −0,213 | 3,25E-05 | 0,0393 |

| PKP1 | 5317 | chr1_HCshore:201252407–201253409; chr1_ICshore:201252275-201253817 | HC | 201252579 | −0,175 | 4,21E-05 | 0,0393 |

| FAM118A | 55007 | chr22:45705265 | HC | 45705080 | −0,279 | 4,32E-05 | 0,0393 |

| CEBPE | 1053 | chr14:23588162 | IC | 23588819 | −0,134 | 4,47E-05 | 0,0393 |

| CORO7 | 79585 | chr16:4465731 | ICshore | 4465897 | −0,144 | 4,50E-05 | 0,0393 |

| CHST8 | 64377 | chr19:34175481 | IC | 34175433 | −0,145 | 8,08E-05 | 0,065 |

| NAA40 | 79829 | chr11:63705946 | HC | 63706441 | 0,107 | 9,22E-05 | 0,0674 |

| CELSR1 | 9620 | chr22_HCshore:46931364–46934654; chr22_ICshore:46929131-46935234 | HC | 46933066 | −0,205 | 9,97E-05 | 0,0674 |

Abbreviations: high-density CpG island (HC), intermediate-density CpG island (IC), region of intermediate-density CpG island that borders HCs (ICshore).

Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood using QiaGen Maxiprep kit (Qiagen, Germany) [16].

Ethics

All participants and their guardians gave informed written consent and the study was approved by the Greek Ministry of National Education (7055/C7-Athens, 19-01-2007) and the Ethical Committee of Harokopio University (16/ Athens, 19-12-2006).

DNA methylation profiling

The genome-wide Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation27 Bead-Chip array (Illumina, USA) which allows interrogation of 27578 CpG dinucleotides covering 14495 genes was applied to determine the methylation profile of genomic DNA isolated and purified from the peripheral whole blood. This chip gives a reliable and reproducible estimation of the methylation profile on a genomic scale [17]. First, bisulfite conversion of genomic DNA was performed using the EZ DNA Methylation-Gold™ Kit (Zymo Research, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, 500 ng of DNA was sodium bisulfite-treated, denatured at 98°C for 10 min, and bisulfite converted at 64°C for 2.5 h. After conversion, samples were desulphonated and purified using column preparation. Approximately 200 ng of bisulfate-converted DNA was processed according to the Illumina Infinium Methylation Assay protocol. This assay is based on the conversion of unmethylated cytosine (C) nucleotides into uracil/thymine (T) nucleotides by the bisulfite treatment. The DNA was whole-genome amplified, enzymatically fragmented, precipitated, resuspended, and hybridized overnight at 48°C to Locus-specific oligonucleotide primers on the BeadArray. After hybridization, the C or T nucleotides were detected by single-base primer extension. The fluorescence signals corresponding to the C or T nucleotides were measured from the BeadArrays using the Illumina iScan scanner. Phenotypes, raw data and background-corrected normalized DNA methylation data are available through the GEO database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) with accession numbers GSE27860 for the girls and GSE57484 for the boys.

Data processing and statistical analysis

All downstream data processing and statistical analyses were performed with the statistical software R (www.r-project.org) together with the lumi [18], limma [19] and IMA [20] packages of the Bioconductor project.

Data preprocessing

The fluorescence data were preprocessed using the GenomeStudio 2009.2 (Illumina, USA) software. There are two methods which have been proposed to measure the methylation level. The first one is called β-value, ranging from 0 to 1, which has been widely used to measure the percentage of methylation. This is the method currently recommended by Illumina, but β-values can show severe heteroscedasticity for highly methylated or unmethylated CpGs [21]. The second way to measure the methylation level is called M-value, which is the log2 ratio of the intensities of methylated probe versus unmethylated probe. Even though the β-value has a more intuitive biological interpretation, the M-value is more statistically valid for the differential analysis of methylation levels. Therefore, the M-value method was used for conducting differential methylation analysis.

Quality control

The data were imported and submitted to quality control using a modified version of the IMA.methy450PP function of the IMA package. The following CpG sites and samples were removed: the sites with missing β-values, the sites with detection p-value > 0.05, the sites having less than 75% of samples with detection p-value < 10−5, the probes containing a SNP, the non-specific probes (with a possibility of cross-hybridization), the samples with missing β-values, the samples with detection p-value > 10−5 and the samples having less than 75% of sites with detection p-value < 10−5. A total of 18339 probes were included in the analysis, after discarding 8157 probes that did not reach the quality control together with 1082 probes from the sex chromosomes.

Normalization

Quantile normalization was performed on the M-values of all the 18339 CpG sites using the lumiMethyN function of the lumi package.

Annotation

For better interpretation of the genome-wide methylation patterns, we chose to use the expanded annotation table for the Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation450 Bead-Chip array generated by Price et al. [22]. There are a total of 27578 loci for 27 k array, and 1600 of them are not mapped to 450 k array. For those unmapped loci, we keep their original annotation from the 27 k array. The expanded annotation file was used to determine:

The average methylation value of CpG sites belonging to the same island or island shores (all sites with the same name in the ‘HIL_CpG_Island_Name’ column of the annotation file were averaged). We obtained the average methylation value of 3678 islands/island shores, which reduced the number of interrogated locations to 14235 sites/islands.

Which gene each interrogated CpG site/island may be associated with (“Closest_TSS_gene_name” column of the annotation file).

The distance of each interrogated CpG site/island to the closest TSS (Transcription Start Site) (“Distance_closest_TSS” column of the annotation file).

The CpG density surrounding each interrogated CpG site/island (‘HIL_CpG_class’ column of the annotation file). Each site can either be located in a high-density CpG island (HC), an intermediate-density CpG island (IC), a region of intermediate-density CpG island that borders HCs (ICshore), or a non-island. Indeed, the local CpG density has been shown to influence the role of methylated cytosines, with methylation having more transcriptional effect in high-density CpG island and less at non-islands [23].

The Illumina-provided MAPINFO GenomeStudio column was used to determine the genomic location of each interrogated CpG site. For CpG islands, the name of the island was used to determine its genomic location (e.g. the island “chr19_IC:17905037-17906698” would be a CpG island of intermediate density located on chromosome 19, between 17905037 and 17906698).

Data processing

Linear model

We developed the following linear model for each CpG site k, using limma’s robust regression method, with a maximum number of iteration equal to 10000:

where Mk is the M-value of CpG site k, G is the dichotomized gender (female=0 and male=1), T is the Tanner stage, B is the white blood cell count, W is the dichotomized weight category (normal-weight=0 and obese=1).

We also used the same linear model, but we added the STK33 rs4929949 polymorphism as an additional variable, with a higher score for a higher number of risk alelles (TT=0, TC=1 and CC=2).

The coefficients bkx summarize the correlation between the methylation level and the variables of interest. Moderated t-statistics for each contrast and CpG site were created using an empirical Bayes model as implemented in limma (eBayes command), in order to rank genes in order of evidence for differential methylation [19]. To control the proportion of False Positives, p-values were adjusted for multiple comparisons as proposed by Benjamini and Hochberg (BH). An adjusted p-value > 0.05 was considered non-significant.

RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis

Mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation and the brain and external organs were removed and dissected within 10 minutes. After dissection the tissue was immersed into RNALater solution (Ambion, USA) and kept at room temperature for 1 hour. Individual tissue samples were homogenized using a Bullet Blender (Next Advance, USA) in RNA-later solution. mRNA was extracted from tissues using an Absolutely RNA Miniprep Kit (Agilent Technologies, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA concentration was determined using a NanoDrop ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific,USA). cDNA was synthesized using a First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Fisher Scientific, Sweden) with random hexamers as primers according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Quantitative real-time PCR

cDNA was analyzed with quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) on MyIQ (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Sweden). All primers were designed with Beacon Designer v4.0 (Premier Biosoft, USA). GAPDH and β-actin were used as housekeeping genes. Each real-time PCR reaction with a total volume of 20 μL contained cDNA synthesized from 25 ng of total RNA; 0.25 μmol/L of each primer, 20 μmol/L Tris/HCl (pH 8.4), 50 μmol/L KCl, 4 μmol/L MgCl2, 0.2 μmol/L dNTP, SYBR Green (1: 50 000). Real-time PCR was performed with 0.02 u/μL Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen, Sweden). 30 seconds at 95°C, followed by 50 cycles of 10 seconds at 95°C, 30 seconds at 59-61°C and 30 seconds at 72°C. Lastly, 5 minutes at 72°C and 10 seconds at 55°C. All RT-PCR plates had negative controls included for each primer pair, and triplicates for each sample were used. The RT-PCR experiments were performed twice to confirm the results. For normalization all tissue cDNA were also run with six different primers for mouse housekeeping genes (mGAPDH, mbTUB, mRPL19, mH3b, mCyclo and mActb). A combined normalization factor for all the housekeeping primers was calculated for each tissue using the GeNorm program.

In situ hybridization

Design and synthesis of RNA probes

Antisense probes were generated from commercial mouse cDNA clones (Source BioScience). The clones were sequenced (Eurofins MWG Operon, Germany) and verified to be correct. Plasmids were linearized with appropriate restriction enzymes and the probes were synthesized using 1 μg vector as template with T7, Sp6 or T3 RNA polymerase in the presence of digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled 11-UTP (Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland). Probes were controlled and quantified using the Nanodrop ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, USA).

In situ hybridization on free floating sections

Free floating sections were washed in PBT followed by 6% hydrogen peroxide treatment at room temperature. After successive washing in PBT the sections were treated with 20 μg/ml proteinase K (Invitrogen). The sections were post-fixed in 4% formaldehyde before pre-incubation in the hybridization buffer (50% formamide, 5xSCC pH 4.5, 1% SDS, 50 μg/ml tRNA (Sigma Aldrich, Sweden), and 50 μg/ml heparin (Sigma Aldrich, Sweden) in PBT). Hybridization of sections in presence of 100 ng probe/ml was performed overnight at 58°C. To remove the unbound probe the sections were washed with buffer 1 (50% formamide, 2xSSC ph4.5 and 0.1% Tween-20 in PBT) followed by buffer 2 (50% formamide, 0.2XSSC pH 4.5 and 0.1% Tween-20 in PBT). The sections were incubated in the blocking solution (1% blocking reagent; Roche Diagnostics, Stockholm) followed by overnight incubation combined with 1:5000 diluted anti-digoxigenin alkaline phosphates conjugated antibody (Roche Diagnostics Scandinavia, Sweden). Unbound antibodies were washed away with sequential washes with 0.1% Tween-20 Tris-buffered saline (TBST). The sections were then developed using Fast Red (Roche Diagnostics, Sweden). Sections were photographed using a Zeiss LSM 510 Meta confocal microscope and analyzed with AxioVision Rel. 4.8 software (Zeiss, Germany).

Immunofluorescence

C57/Bl6 adult male mice (n=5) were housed in a controlled environment (21°C, 12:12 LD cycle) with ad libitum access to standard chow and water. Mice were deeply anesthetized by introperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital and perfused through the left heart ventricle with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and 4% formaldehyde. Brains were postfixed overnight in 4% formaldehyde at 4°C followed by embedding in 4% agarose gel and sectioned using a vibratome (Leica vt1200s) at 50 μm. Sections were washed in PBS and 0.5% Triton X-100 (PBT) followed by incubation in 1x blocking reagent (Roche, Germany) and 5% normal donkey serum (Abcam, Cambridge, CA) at room temperature for 1 hour. Primary antibodies: rabbit anti-coronin 7 (Abcam, Cambridge, CA, diluted 1:50 in PBT), mouse anti-PAG (Abcam, UK. diluted 1:200 in PBT) were added onto slides and incubated at 4°C for 72 hours. The sections were then washed with PBT and incubated in the secondary antibodies: Alexa Fluor 594 donkey anti rabbit (1:500, Invitrogen, Sweden), Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-mouse (1:500, Invitrogen, Sweden) combined with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Roche, Germany) for nuclear staining; for 4 hours. Sections were mounted using Mowiol 4–88 (Sigma-Aldrich, Sweden). Sections were photographed using a Zeiss LSM 510 Meta confocal microscope and analyzed with AxioVision Rel. 4.8 software (Zeiss, Germany).

Feeding experiments

Male C57BL/6 J mice housed in macrolon cages, under 12:12 light–dark cycle were used for both feeding experiments. Water and standard chow were available ad libitum during all times unless otherwise specified.

-

Experiment 1. mRNA levels following 24 h of food deprivation

Chow was removed before the onset of the dark phase and mice (n=8) were decapitated between 1000 and 1200 on the next day. Control mice (n=8) had ad libitum access to food.

-

Experiment 2. mRNA levels upon increased body weight

Mice received high fat diet in addition to chow for 8 weeks; controls had chow only (n=8/group). During the start of the experiments there were no differences in body weight between the two groups but after 8 weeks the mice on the high-fat diet had increased in weight over the control values.

Mice were decapitated between 1000 and 1200.

-

Experiment 3. Treatment with ethanol

Mice were injected with saline or 2.0 g/kg b. wt [15% (w/v)] ethanol. Mice had water and food taken away just prior to the injection. Perfusion (according to the protocol described above) was performed 1.5 h later.

Ethical statement

All animal procedures were approved by the local ethical committee in Uppsala and follows international guidelines.

Phylogenetic analyses

All known amino acid sequences of coronin gene families present in vertebrate genomes were identified and retrieved from the Ensembl database, release 76. Coronin sequences were retrieved from the following species: Homo sapiens, Mus musculus, Gallus gallus, Anolis carolinensis, Xenopus tropicalis and Takifugu rubripes. In cases where several transcripts were present in the database the longest transcript was used for further analysis. To ensure whether additional sequences are present in these genomes as well as to mine coronin gene families in insects and nematodes, we built a hidden Markov model (HMM) profile using the sequences obtained from the Ensembl database. The HMM profile was then used as a query to identify all coronin like sequences in the genomes of Drosophila melanogaster, Drosophila pseudoobscura, Anopheles gambiae, Caenorhabditis elegans. Also, using the same HMM profile, we performed a secondary search in the vertebrate genomes to ensure a final list of coronin sequences. The final list contained 52 coronin sequences from 10 organisms and was used for further phylogenetic analysis.

Multiple sequence alignment of the coronin sequences were created using the MAFFT program (http://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/server/), with BLOSUM62 as the scoring matrix and using option E-INS-I [24]. The final sequence alignment was used to construct phylogenetic trees employing maximum likelihood (ML) method and Bayesian phylogenetic inference. Maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic trees were estimated by MEGA 5.2 [22] Statistical support for the branches was estimated by performing 500-bootstrap replicates with Jones-Taylor-Thornton (JTT) as amino acid model. Gamma distribution with invariant sites (G + I) was used to model evolutionary rate differences among sites and the number of discrete Gamma categories was set to 5. Bayesian inference trees were estimated with MrBayes version 3.1.2 [23]. Posterior probability of the trees was estimated using Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) analysis with two parallel runs for 300,000 generations and sampling every hundredth tree. Runs were stopped when the average standard deviation of split frequencies of the two parallel runs was <0.01. A consensus tree was built from the 75% of the sampled trees after first 25% burnin samples were discarded.

Drosophila melanogaster

Fly husbandry

Flies were maintained at 25°C with 50% relative humidity in a 12:12 h light:dark cycle. Drosophila stocks and crosses were reared on standard Drosophila medium of sugar-cornmeal-yeast-agar. The following strains were used: w1118, UAS-pod1RNAi (y1sc*v1; P{y[+t7.7] v[+t1.8]=TRiP.HMS02270)attP2) and elav-GAL4;tubGAL80ts (P{GawB}elavC155 w*; P{FRT(whs)}G13 P{tubP-GAL80}LL2), were obtained from Bloomington Drosophila stock center (BDSC, USA).

Genetic crosses

Virgin females from elav-GAL4;tubGAL80ts were collected and crossed with male UAS-pod1RNAi. Two different controls were crossed: virgin females from w1118 with male UAS−pod1RNAi, and virgin females from elav-GAL4;tubGAL80ts with male w1118. To avoid RNAi-inhibition of pod1 during development, the Gal4/UAS/Gal80 conditional system was used. The RNAi block of pod1 was activated after eclosion by incubating adult flies for 4 days at 29°C.

Macronutrient diets

All diets consisted of varing concentrations (g/dl) of sucrose (Sigma, Sweden) or yeast extract (VWR, Sweden) in 1% agarose. Newly eclosed adult males were maintained on these diets for 5 days at 25°C, 60% humidity on a 12:12 h light:dark cycle.

RNA extraction

RNA was extracted by homogenizing 40 fly heads in PBS. An equal volume of phenol: choloroform: isoamyl alcohol solution (25:24:1) was added to the homogenized flies and mixed.

The solution was centrifuged for 5 minutes at 12,000 g at room temperature. The aqueous phase was transferred to a new tube and an equal volume of chloroform was added followed b centrifugation at previously mentioned speed and time.

Ethanol and silica suspension (1 g/ml) was added to the aqueous phase and incubated for 1 min before an additional centrifugation. The pellet was washed with 70% ethanol and let dry. To remove any DNA the sample was treated with DNAse for 30 minutes at 37°C and subsequently at 65°C for 15 minutes.

The pellet was resolved in 50 ul DEPC-H2O and incubated for 5 minutes. To remove the silica suspension the sample was centrifuged and the RNA solution was transferred to new tube. A spectrophotometer (model ND-1000, Nanodrop) was used to measure total RNA concentration.

cDNA synthesis

High capacity RNA to cDNA kit was used for cDNA synthesis (Applied Biosystems, Sweden) and performed accordingly to manufactures instructions.

Starvation assay

Starvation resistance was measured by placing 20 male flies, which were 5 to 7 days old, in a vial containing 5 ml of 1% agarose, which provides water and humidity but no food source. The vials were kept at 25°C in a incubator, on a 12 h:12 h light:dark cycle. The numbers of dead flies was counted every 12 hours. This allowed for the calculation of the median time of death and survival rate. At least 10 replicates for each genotype were conducted.

Results

DNA methylation profiling and analysis of genetic association to obesity

To establish if there is a correlation between weight category and methylation levels of CpG sites/islands we investigated the genome-wide methylation profile using whole blood obtained from obese and normal-weight participants. From the first linear model, which was adjusted for age, sex, Tanner stage and white blood cell count, we selected the top 15 sites/islands whose methylation levels correlated with a particular weight category (Table 1). Next, a second linear model was used, adjusted for the same confounders and weight category, where we selected the top 15 sites/islands whose methylation levels correlated with the obesity-linked gene STK33 rs4929949 polymorphism (Table 2), which we previously demonstrated is associated with obesity in two independent children cohorts [25]. This SNP data was consequently used to stratify the methylation data in order to determine if there was a common gene designated by both linear models. Interestingly, only one CpG site in the top 15 for weight category (chr 16:4465731) and another that correlated with the STK33 rs4929949 polymorphism (chr16:4466650), corresponded to the same gene, CORO7 (Tables 1 and 2). Even though these sites were distinct they displayed a consistent pattern. The site found for weight category was less methylated in obese children, and the site found for rs4929949 was less methylated in children with a higher number of obesity risk alleles. Given that CORO7 was the only gene retrieved by both linear models and from a functional perspective it was not as well characterized as the other significant genes, we decided to perform further functional tests to clarify a potential role for CORO7 in metabolic regulation. Furthermore, such a study would be proof of concept if such a genome wide methylation measurement approach could be useful in identifying novel mechanisms regulating body weight.

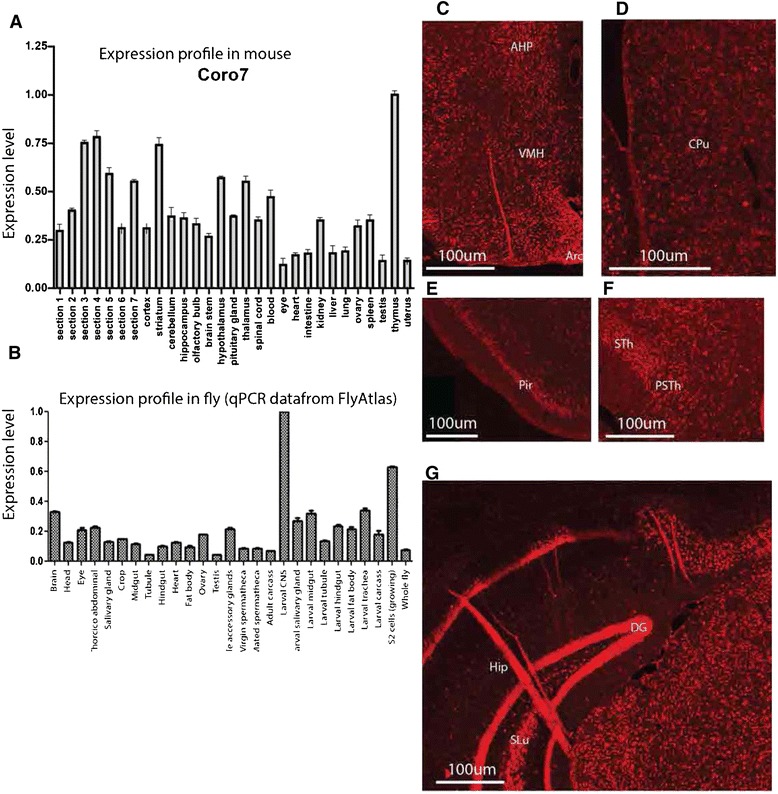

High mRNA expression of Coro7 in the central nervous system

The expression pattern of Coro7 mRNA was investigated in a wide range of mouse tissues using quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR), in total 18 different tissues were examined, including 8 brain slices representing the entire brain. The value of the tissue with the highest expression, the thymus, was set to 1 and relative expression values were displayed as changes in relation to this tissue. As mentioned, the highest expression was found in the thymus, this was followed by expression levels in the striatum, hypothalamus and thalamus (Figure 1A). Moderate mRNA levels were found in the entire brain and the intestine, while blood cells had the lowest level of Coro7 expression (Figure 1A). As a comparison, microarray expression data for the Drosophila melanogaster Coro7 homologue pod1 was downloaded from FlyAtlas [26]. Similar to mouse Coro7, pod1 expression was ubiquitous, but had higher expression levels in the brain (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Coro7 mRNA expression and tissue distribution in mouse periphery and brain. (A,B) Relative mRNA expression of the Coro7 gene was investigated in two species using real-time PCR. (A) Means are relative to tissue with the highest expression (set to 1) in mouse. (B) The expression of the CORO7 fly homolog pod1 was received from FlyAtlas microarray database, the expression is relative to the whole fly. Error bars represent SEM. (C-G) Floating fluorescent in situ hybridization on coronal sections using digoxigenin-labelled mouse Coro7 antisense probe to detect Coro7 mRNA expression patter. (C) hypothalamus, anterior hypothalamic part, posterior part (AHP), arcuate hypothalamic nucleus (Arc), ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus (VMH), (D) striatum, caudate putamen (CPu), (E) Piriform cortex (pir), (F) thalamus, subthalamic nucleus (STh), parasubthalamic nucleus (PSTh), (G) dentate gyrus (DG), stratum lucidum (SLu) hippocampus (hip). Scale bar: 0.2 mm.

A detailed characterization of the Coro7 expression pattern in adult mouse brain was accomplished using in situ hybridization on a large number of coronal sections. The widespread Coro7 mRNA distribution observed in the CNS correlated well with results obtained from the qPCR expression profile, Coro7 was highly expressed throughout the CNS. Intriguingly, Coro7 expression was found in food intake and energy homeostasis regulation areas, such as the arcuate nucleus, the anterior hypothalamic area, posterior part and ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus (Figure 1C). The caudate putamen also showed strong expression (Figure 1D). Furthermore, high expression levels were observed in all cortical layers except 1, as well as in the piriform cortex (Figure 1E). Furthermore, the subthalamic nucleus and hippocampus had widespread expression levels with strong intensity (Figure 1F and G).

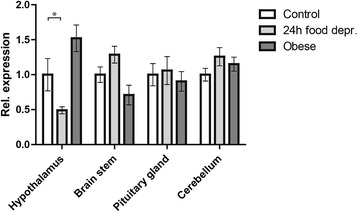

The effect of food restriction on CNS Coro7 expression

Next, using qPCR, the expression level of Coro7 mRNA was investigated in mice maintained under different dietary regimes. Depriving adult male mice of food for 24-hours resulted in a statistically significant decrease in Coro7 hypothalamic expression (34%, SD ± 3.1%, P < 0.05). Although, diet-induced obese mice had a 29% increase of Coro7 expression in the hypothalamus it was not statistically significant (SD ± 5.5%, P > 0.1) (Figure 2). Other areas investigated included the pituitary gland, brain stem and cerebellum, where no significant change in either food-deprived or diet-induced obese mice was observed.

Figure 2.

Changes in Coro7 expression levels in mice under different nutritional states. The levels of Coro7 were analyzed in mice using three different dietary parameters: control, deprived and obese mice. Expression levels were analyzed in 29 different brain structures and peripheral organs as well as seven brain sections encompassing the entire brain. The one with significant changes are shown. All data where normalized to the mean value of the control group and significance levels were obtained by one-way ANOVA. Error bars indicate SD. Each group contained eight different male C57BL/6 mice. Significance levels are indicated: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P <0.001. Each group contained eight male mice.

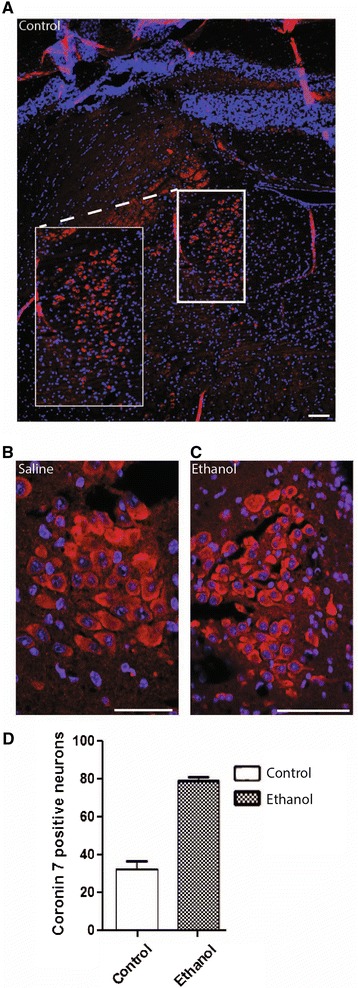

Increase in the number of Coro7 locus coeruleus neurons in ethanol-treated mice

The locus coeruleus is a noradrenergic site involved in the regulation of complex behavioral and physiological processes, including appetite, arousal and stress homeostasis [27]. Neurons in the locus coeruleus are known to respond to the appetite suppressant ethanol [12,13] (Figure 3A-C). Intriguingly, treating mice with ethanol resulted in an 84% (SD ± 7.5%, P < 0.005) increase in the number of Coro7 positive neurons within the locus coeruleus, compared to mice injected with saline (Figure 3B-D).

Figure 3.

Expression of Coro7 in locus coeruleus (LC) in mouse treated with ethanol. Mice were treated with saline or ethanol and cells expressing Coro7 in the locus coeruleus was visualized using Coro7 antibody. (A) Brain was cut coronal and the locus coeruleus is shown as overview. (B) close up from saline treated and (C) ethanol-treated mice. (D) The number of positive cells were counted in LC and displayed as a column chart. Error bars indicate SD. Significance levels are indicated: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P <0.001. Each group contained eight male mice. Scale bar: 0.1 mm.

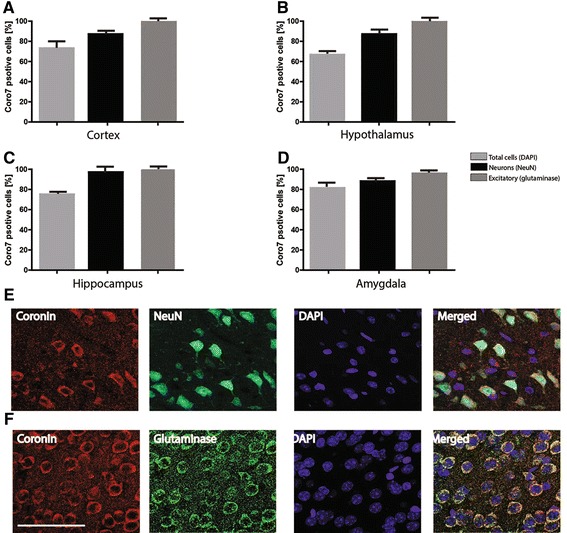

Immunohistochemical detection of coronin 7 in the mouse brain

Double immunofluorescent stainings were used to identify which cell types express Coro7 in the mouse brain (Figure 4A-B). All regions investigated showed a wide distribution of Coro7 positive neurons. In fact, 72% of all the cells in the CNS were found to express Coro7 (Figure 4C-F). The regions with the highest distribution were the hippocampus and hypothalamus, where coronin 7 expression had a 97% overlap with the Neuronal Nuclei (NeuN) antibody, followed by the cortex (88%) and the amygdala (87%) (Figure 4C-F). Furthermore, a subset of neurons was visualized using a marker for phosphoactivated glutaminase, an antibody which is commonly used as a marker for excitatory neurons. In the hypothalamus and hippocampus, 98% and 97% of the excitatory neurons expressed Coro7, respectively (Figure 4D and E).

Figure 4.

Distribution of Coro7 in different regions and cells in mouse brain. Expression of Coro7 protein using immunofluorescence with an anti-coronin 7 antibody was performed in order to investigate the distribution of Coro7 in different cell types and brain regions in mouse brain. Four different brain regions were investigated and the averaged percentages of different cell types positive for coronin 7 were calculated: A. Cortex, B. Hypothalamus, C. Hippocampus and D. Amygdala. (E) Sections were co-stained with DAPI (blue) a nuclear marker, NeuN antibody (green) for neurons and the anti-coronin 7 antibody (red). F. Sections were co-stained with DAPI (blue) a nuclear marker, anti-Glutaminase antibody (green) for excitatory neurons and the anti-coronin 7 antibody (red). Scale bar: 0.1 mm. Error bars indicate SD.

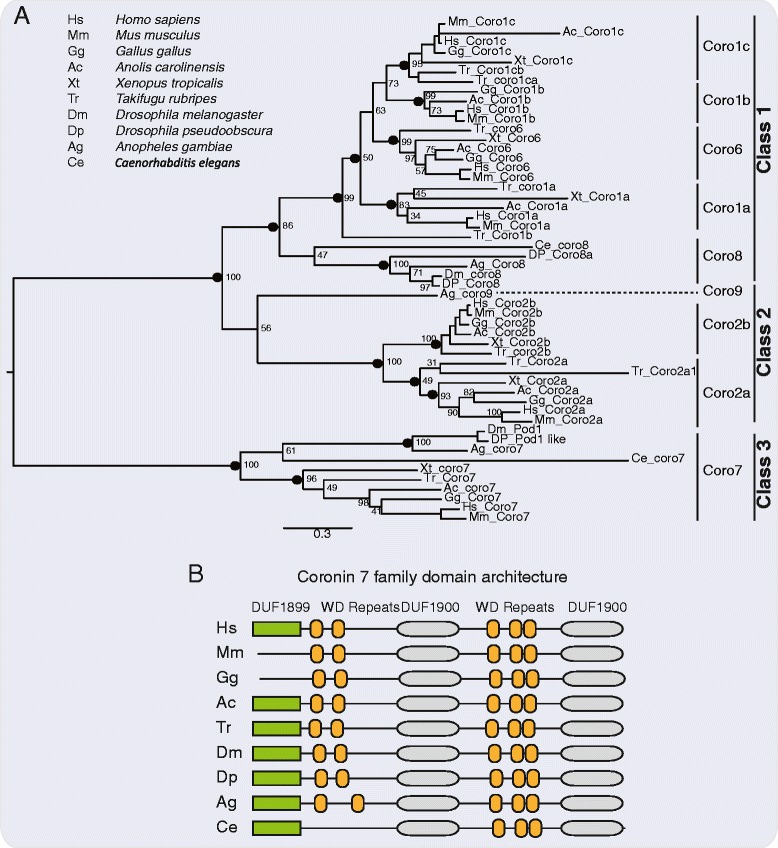

Phylogenetic relationships of CORO7 and other paralogous gene families

To gain insights into the phylogenetic relationships of the coronin 7 family with respect to other paralogous coronin families; we performed phylogenetic analysis using sequences obtained from selected vertebrates and insects, as well as a nematode genome (see Methods for the list of sampled species). Amino acid sequences of the coronin 7 family and other coronin families from vertebrate, insects and nematode genomes were identified (see Methods) and a final list of 52 sequences was utilized to perform phylogenetic analysis. The resulting phylogenetic tree (Figure 5A) showed well defined clusters in accordance with previously defined coronin gene families and classes [28], with high confidence support (Figure 5A). The coronin7-like Pod1 found in D. melanogaster and D. pseudoobscura, as well as the coronin 7-like found in A. gambiae and C. elegans formed a monophyletic clade with the vertebrate coronin 7 gene family (100% PP and 100% BS support; see Figure 5A). This is in accordance with previous observations [8,28], showing further evidence for that D. melanogaster Pod1 is homologous to vertebrate coronin 7. The coronin 7 gene family belongs to class 3 coronins, which seem to have diverged considerably from class I and class II coronins (Figure 5A). This is possibly because coronin 7 proteins are relatively longer than class I and class II coronins, containing two WD-repeat domains (Figure 5B). Also, it is worth mentioning that a recent evolutionary mining of coronins showed that coronin 7 is the most widespread family among all coronins, suggesting a crucial role of coronin 7 in most eukaryotes.

Figure 5.

Maximum likelihood tree showing phylogenetic relationships of the coronin 7 and other paralogous families. (A) Coronin families and classes are indicated as previously defined [28]. Nodal support was obtained using MEGA 5.2 with 500 bootstrap replicates and posterior probability (PP) was estimated using MrBayes version 3.1.2. Support values are shown for all major nodes defining the clusters. Nodes with PP > 0.9 are shown as black circles and the corresponding percentage bootstrap values are shown. (B) Predicted domain architectures using Pfam search (default settings) are shown for the coronin 7 family.

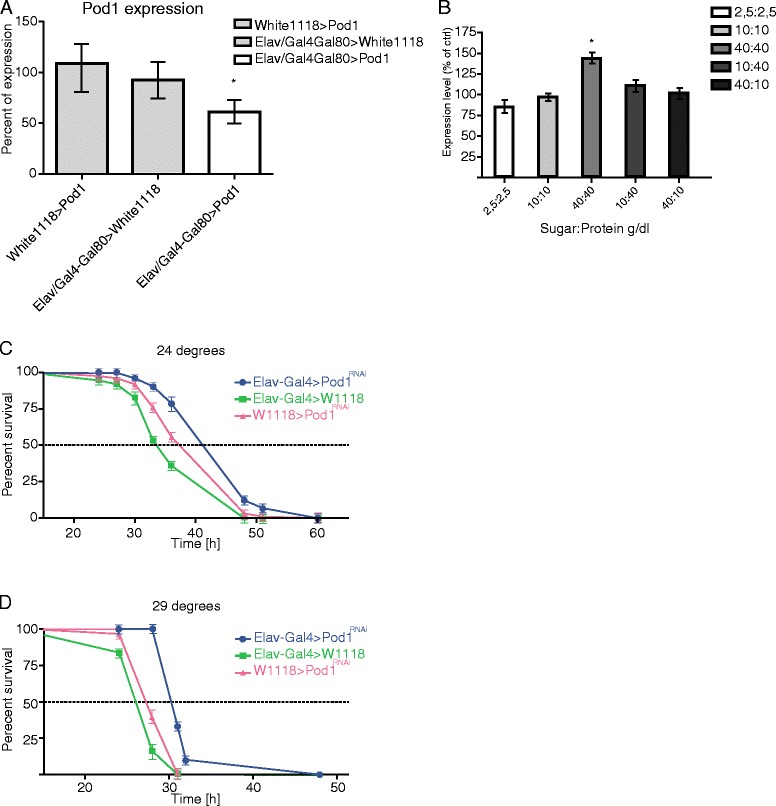

Pod1 affects starvation survival rate in Drosophila melanogaster

To better understand if CORO7 could be involved in regulating metabolic homeostasis we also used the genetically-tractable Drosophila system. Before beginning any assays we clarified whether UAS-pod1RNAi (referred to as pod1RNAi) was functional. Since pod1 was highly expressed in the Drosophila central nervous system [26], we crossed pod1RNAi flies to the elav-GAL4 driver, which expresses in all neurons and performed qPCR to measure pod1 transcript levels. Compared to heterozygous controls, elav-Gal4 > w1118 and w1118 > pod1RNAi, pod1 knockdown flies had only 57% (SEM ± 7.4%, P < 0.05) of normal pod1 expression levels (Figure 6A), confirming that the pod1 RNAi construct is effective.

Figure 6.

Pod1 increases survival to starvation in pod1 KD flies. (A) Relative transcript levels of pod1 were measured using real-time PCR in male flies kept at 29°C to verify the efficiency reduced levels of pod1 mRNA in homozygous pod1 −/− and heterozygous pod1 +/− flies. Flies were aged 5–7 days at 29°C after eclosion. Real-time PCR was repeated 5 times. Statistical significance was validated using one-way ANOVA where *P < 0.05. (B,C) We tested the effect of pod1-knockdown in flies on survival assay. Pod1 +/–and pod1 −/− were placed in a vial containing 1% agarose and maintained at both 24°C (B) and 29°C (C). Percent survival was calculated every 12 h (n=75-95 flies per genotype); *P < 0.05 validated through one-way ANOVA with appropriate post-hoc test for multiple comparisons. (D) To validate how nutritional state affects the expression levels of pod1 mRNA in flies they RNA was extracted from flies during different nutritional states. Error bars indicate SEM. Significance levels are indicated: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P <0.001.

We employed the starvation assay to begin to clarify a role for pod1 in Drosophila metabolic regulation, as it is a simple way to determine if a gene has an influence on metabolism. Any disruption if feeding behavior, lipogenesis, lipolysis or gluconeogenesis will be uncovered using this assay. To investigate whether pod1 influences starvation resistance we knocked it down in all adult neurons using RNAi. UAS-pod1RNAi flies were crossed to the pan-neuronal GAL4 driver elav-GAL4;tubGAL80ts [29]. Since the allele of the GAL4 inhibitor GAL80 is temperature sensitive, with the non-permissive temperature being 29°C [29], this allowed us to control when pod1 RNAi was expressed. Equally aged male flies that were kept on standard lab food were placed in a vial containing 1% agarose, ensuring access to water. The vials were maintained at either 24°C or 29°C and the number of dead flies was counted every 12 hours. Flies deficient for pod1 displayed a resistance to starvation at 24°C compared to controls (p < 0.001 compared to controls) (Figure 6B). There was also a significant increase to resistance when the flies were maintained at 29°C during the starvation assay (p < 0.05 compared to controls) (Figure 6C).

Finally, in order to ascertain if pod1 expression could be affected by macronutrient content, we maintained flies on different diets (see Methods) for 5 days and then used qPCR to determine pod1 expression levels. Subjecting adult male Drosophila to a diet rich in both protein and sugar revealed a 44% increase in pod1 expression levels (SEM ± 4.1%, P < 0.05) compared to normal fed flies. Other diets analyzed did not show any altered levels (Figure 6D).

Discussion

By comparing the top 15 methylation sites/islands associated with weight with the top 15 sites/islands associated with the obesity-related STK33 rs4929949 SNP, we found two CpG sites located near the promoter of CORO7: one CpG site displayed lower methylation levels in obese children and the other site displayed lower methylation levels in carriers of the rs4929949 risk allele. Our data suggests that the epigenetic regulation of CORO7 could be associated with body weight, with decreased promoter methylation in obese subjects, which commonly leads to higher gene expression [30].

To investigate coronin 7 further, we performed a comprehensive characterization of Coro7 expression throughout the mouse body and brain using qPCR and in situ hybridization. Intriguingly, Coro7 is expressed in important food-regulation areas within the brain such as the hypothalamus, ventral striatum and amygdala. These results are in good agreement with other studies, which demonstrated that Coro7 is expressed in the hypothalamus of murine embryos [8]. Furthermore, our immunohistochemical results demonstrated that Coro7 is found in all major brain areas, including the hypothalamus and hippocampus that had Coro7 expression in 97% of all neurons. The distribution of Coro7 positive staining in all neurons within the CNS was 77%. These data confirm a ubiquitous expression of coronin 7 and overlap with the qPCR and the in situ hybridization data. The hypothalamus is a major part of the energy homeostasis network [31], considering that CORO7 was presented as a gene that is associated with obesity, it is very interesting that we find Coro7 positive neurons to such a high degree within the hypothalamus.

The immunohistochemical stainings also revealed Coro7 to be highly expressed in the locus coeruleus. Axons of neurons whose cell bodies are located within the locus coeruleus act on adrenergic receptors in a whole variety of brain regions including: the amygdala, hippocampus, thalamus, striatum, spinal cord, as well as the hypothalamus [32]. As the locus coeruleus is the major noradrenaline synthesizing site, and many of its noradrenergic neurons project to the hypothalamus [32], the fact that Coro7 is expressed therein suggests a link between Coro7 and the noradrenergic regulation of the hypothalamus.

It is well known that locus coeruleus neurons respond to appetite changing treatments, including ethanol injections [33,34]. In our study, we noted a significant increase in the number of Coro7 positive neurons within the locus coeruleus in ethanol-injected mice. Depletion of Coro7 in cell culture results in breakdown of the Golgi apparatus, as well as an accumulation of arrested proteins [35]. This suggests that Coro7 is involved in the later stages of cargo sorting and export of proteins from the Golgi complex, where Coro7 acts as a mediator of cargo vesicle formation and protein sorting [35].

Given that Coro7 is expressed to such a high degree in the locus coeruleus, Coro7 might be involved in the transport of noradrenaline in the brain and thus regulate central feeding circuits that receive noradrenergic input. Interestingly, it was reported that depriving rats of food reduces the volume and number of neurons in the locus coeruleus [36]. Studies have demonstrated that exogenous injection of noradrenaline can both suppress, as well as to induce feeding, acting via a1-and a2-adrenoceptors to modulate eating [37,38]. Furthermore, changes in body weight affect gene expression in mice [39]. Changes in energy needs of an organism, as well as body weight, affect gene expression. The fact that Coro7 expression was significantly down-regulated in the hypothalamus of mice under food deprivation provides further support that this gene could have a regulatory role in the central feeding circuits.

The homologue to CORO7 in D. melanogaster is called pod1. In Drosophila, Pod1 is located at the tip of growing axons, where it is involved in the crosslinking of actin and microtubules [11]. The human CORO7 shows a similar molecular architecture to its homologues in Drosophila and C. elegans (see Figure 5B). More specifically it has 46% and 47% similarity and 30% and 29% identical to Drosophila Pod1 and C. elegans Pod1, respectively. Using the GAL4-UAS system we reduced pod1 expression specifically in neurons and performed a starvation assay. We found pod1 mutant flies displayed significantly more resistance to starvation than control flies. The decrease in susceptibility to starvation could be due to change in feeding behavior, lipogenesis, lipolysis or gluconeogenesis in the fly making it able to survive starvation. Flies being subjected to a diet rich in both protein and sugar had significantly increased levels of pod1 mRNA expression, compared to normal fed flies; this links the role of the CORO7 homolog with both energy-and macronutrient/reward-driven feeding. These data, combined with the human and mouse studies, suggest a conserved function involving coronin 7 to homeostatic control and regulation of energy and food intake. In mammals this could be, for example, due to an interplay between the hypothalamus, striatum and the locus coeruleus, with noradrenaline as the neurotransmitter. We find Coro7 mRNA in sites important for energy balance but also in regions involved in reward.

Conclusion

In conclusion, several strengths and limitations apply to the findings of this study. We do not provide a full explanation on how Coro7 might alter the metabolism in mice or how the CORO7 DNA methylation levels affect the obese/normal-weight individuals, we merely show an association. Furthermore, in regards to the findings in this study it is evident that we need to expand the line of experiments in order to be able to provide a complete functional and molecular characterization of coronin 7 in terms of energy homeostasis. This will also further prove the importance of coronin 7 in respect to metabolism in both humans and mice, as well as in the fruit fly.

Acknowledgements

The methylation array was performed at the Genotyping Technology Platform, Uppsala, Sweden (http://www.genotyping.se), with support from Uppsala University and the Knut and Alice Wallenberg foundation, and at the Uppsala Genome Centre. This study was supported by the Swedish Research Council, as well as the Åhléns Foundation, The Swedish Brain Research Foundation, Carl Tryggers Stiftelse, Stiftelsen Olle Engkvist Byggmästare and Stiftelsen Lars Hiertas Minne.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

AE carried out molecular genetic studies drafted the manuscript; MJW carried out molecular genetic studies drafted the manuscript; SV performed human genetic studies and helped draf that section of the manuscript; ID carried out molecular genetic studies; AK performed phylogenetic studies and drafted that section of the manuscript; GP carried out molecular genetic studies; OY carried out molecular genetic studies; FM carried out molecular genetic studies; GP provided human genetic data; YM provided human genetic data; GPC provided human genetic data; PKO carried out molecular genetic studies and helped draft the manuscript; RF helped draft the manuscript; HBS helped draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Anders Eriksson, Email: anders.eriksson@neuro.uu.se.

Michael J Williams, Email: Michael.Williams@neuro.uu.se.

Sarah Voisin, Email: sarah.voisin.aeris@gmail.com.

Ida Hansson, Email: idaehansson@gmail.com.

Arunkumar Krishnan, Email: arunkumar.krishnan@neuro.uu.se.

Gaetan Philippot, Email: gaetan.philippot@ebc.uu.se.

Olga Yamskova, Email: olga.yamskova@gmail.com.

Florence M Herisson, Email: florence.herisson@gmail.com.

Rohit Dnyansagar, Email: rohit.dnyansagar@gmail.com.

George Moschonis, Email: gmoschi@hua.gr.

Yannis Manios, Email: manios@hua.gr.

George P Chrousos, Email: chrousge@med.uoa.gr.

Pawel K Olszewski, Email: pawel@waikato.ac.nz.

Robert Frediksson, Email: robert.fredriksson@neuro.uu.se.

Helgi B Schiöth, Email: helgi.schioth@neuro.uu.se.

References

- 1.Lewis CE, McTigue KM, Burke LE, Poirier P, Eckel RH, Howard BV, et al. Mortality, health outcomes, and body mass index in the overweight range: a science advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2009;119:3263–3271. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maes HH, Neale MC, Eaves LJ. Genetic and environmental factors in relative body weight and human adiposity. Behav Genet. 1997;27:325–351. doi: 10.1023/A:1025635913927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thorleifsson G, Walters GB, Gudbjartsson DF, Steinthorsdottir V, Sulem P, Helgadottir A, et al. Genome-wide association yields new sequence variants at seven loci that associate with measures of obesity. Nat Genet. 2009;41:18–24. doi: 10.1038/ng.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hofker M, Wijmenga C. A supersized list of obesity genes. Nat Genet. 2009;41:139–140. doi: 10.1038/ng0209-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Speliotes EK, Willer CJ, Berndt SI, Monda KL, Thorleifsson G, Jackson AU, et al. Association analyses of 249,796 individuals reveal 18 new loci associated with body mass index. Nat Genet. 2010;42:937–948. doi: 10.1038/ng.686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Youngson NA, Morris MJ. What obesity research tells us about epigenetic mechanisms. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2013;368:20110337. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McArdle B, Hofmann A. Coronin structure and implications. Subcell Biochem. 2008;48:56–71. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-09595-0_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rybakin V, Stumpf M, Schulze A, Majoul IV, Noegel AA, Hasse A. Coronin 7, the mammalian POD-1 homologue, localizes to the Golgi apparatus. FEBS Lett. 2004;573:161–167. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.07.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rybakin V. Role of Mammalian coronin 7 in the biosynthetic pathway. Subcell Biochem. 2008;48:110–115. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-09595-0_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rybakin V, Rastetter RH, Stumpf M, Uetrecht AC, Bear JE, Noegel AA, et al. Molecular mechanism underlying the association of Coronin-7 with Golgi membranes. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:2419–2430. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8278-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rothenberg ME, Rogers SL, Vale RD, Jan LY, Jan YN. Drosophila pod-1 crosslinks both actin and microtubules and controls the targeting of axons. Neuron. 2003;39:779–791. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00508-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blackburn RE, Stricker EM, Verbalis JG. Acute effects of ethanol on ingestive behavior in rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1994;18:924–930. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1994.tb00061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fujita N, Sakamaki H, Uotani S, Takahashi R, Kuwahara H, Kita A, et al. Acute effects of ethanol on feeding behavior and leptin-induced STAT3 phosphorylation in rat hypothalamus. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27:55–59. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moschonis Social, economic and demographic correlates of overweight and obesity in primary-school children: preliminary data from the Healthy Growth Study. Public Health Nutr. 2010;13:1693–1700. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010002247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Almén MS, Jacobsson JA, Moschonis G, Benedict C, Chrousos GP, Fredriksson R, et al. Genome wide analysis reveals association of a FTO gene variant with epigenetic changes. Genomics. 2012;99:132–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2011.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobsson Major gender difference in association of FTO gene variant among severely obese children with obesity and obesity related phenotypes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;368:476–82. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.01.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bibikova Genome-wide DNA methylation profiling using Infinium (R) assay. Epigenomics. 2009;1:177–200. doi: 10.2217/epi.09.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Du lumi: a pipeline for processing Illumina microarray. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:1547–1548. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smyth Linear models and empirical Bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2004;3:1–25. doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang IMA: An R package for high-throughput analysis of Illumina’s 450K Infinium methylation data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:729–730. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Du Comparison of Beta-value and M-value methods for quantifying methylation levels by microarray analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:587. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1572–1574. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katoh K, Standley DM. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rask-Andersen M, Moschonis G, Chrousos GP, Marcus C, Dedoussis GV, Fredriksson R, et al. The STK33-linked SNP rs4929949 is associated with obesity and BMI in two independent cohorts of Swedish and Greek children. PLoS One. 2013;8:e71353. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chintapalli VR, Wang J, Dow JAT. Using FlyAtlas to identify better Drosophila melanogaster models of human disease. Nat Genet. 2007;39:715–720. doi: 10.1038/ng2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berridge CW, Waterhouse BD. The locus coeruleus-noradrenergic system: modulation of behavioral state and state-dependent cognitive processes. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2003;42:33–84. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0173(03)00143-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eckert C, Hammesfahr B, Kollmar M. A holistic phylogeny of the coronin gene family reveals an ancient origin of the tandem-coronin, defines a new subfamily, and predicts protein function. BMC Evol Biol. 2011;11:268. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-11-268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fujimoto E, Gaynes B, Brimley CJ, Chien CB, Bonkowsky JL. Gal80 intersectional regulation of cell-type specific expression in vertebrates. Dev Dyn. 2011;240:2324–2334. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sunahori K, Juang YT, Kyttaris VC, Tsokos GC. Promoter hypomethylation results in increased expression of protein phosphatase 2A in T cells from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol. 2011;186:4508–4517. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Woods SC, Schwartz MW, Baskin DG, Seeley RJ. Food intake and the regulation of body weight. Annu Rev Psychol. 2000;51:255–277. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Delaville C, Deurwaerdère PD, Benazzouz A. Noradrenaline and Parkinson’s disease. Front Syst Neurosci. 2011;5:31. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2011.00031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maier SE, West JR. Alcohol and nutritional control treatments during neurogenesis in rat brain reduce total neuron number in locus coeruleus, but not in cerebellum or inferior olive. Alcohol. 2003;30:67–74. doi: 10.1016/S0741-8329(03)00096-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Selvage D. Roles of the locus coeruleus and adrenergic receptors in brain-mediated hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis responses to intracerebroventricular alcohol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36:1084–1090. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01707.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rybakin V, Clemen CS. Coronin proteins as multifunctional regulators of the cytoskeleton and membrane trafficking. Bioessays. 2005;27:625–632. doi: 10.1002/bies.20235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pinos H, Collado P, Salas M, Pérez-Torrero E. Undernutrition and food rehabilitation effects on the locus coeruleus in the rat. Neuroreport. 2004;15:1417–1420. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000132772.64590.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leibowitz SF. Hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus: interaction between alpha 2-noradrenergic system and circulating hormones and nutrients in relation to energy balance. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1988;12:101–109. doi: 10.1016/S0149-7634(88)80002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wellman PJ, Davies BT, Morien A, McMahon L. Modulation of feeding by hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus alpha 1- and alpha 2-adrenergic receptors. Life Sci. 1993;53:669–679. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(93)90243-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Muthulakshmi S, Chakrabarti AK, Mukherjee S. Gene expression profile of high-fat diet-fed C57BL/6J mice: in search of potential role of azelaic acid. J Physiol Biochem 2015. doi:10.1007/s13105-014-0376-6. [DOI] [PubMed]