Abstract

The accumulation of misfolded proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) activates the Unfolded Protein Response (UPRER) to restore ER homeostasis. The AAA+ ATPase p97/CDC-48 plays key roles in ER stress by promoting both ER protein degradation and transcription of UPRER genes. Although the mechanisms associated with protein degradation are now well established, the molecular events involved in the regulation of gene transcription by p97/CDC-48 remain unclear. Using a reporter-based genome-wide RNAi screen in combination with quantitative proteomic analysis in Caenorhabditis elegans, we have identified RUVB-2, a AAA+ ATPase, as a novel repressor of a subset of UPRER genes. We show that degradation of RUVB-2 by CDC-48 enhances expression of ER stress response genes through an XBP1-dependent mechanism. The functional interplay between CDC-48 and RUVB-2 in controlling transcription of select UPRER genes appears conserved in human cells. Together, these results describe a novel role for p97/CDC-48, whereby its role in protein degradation is integrated with its role in regulating expression of ER stress response genes.

Keywords: AAA+ ATPase, proteostasis, UPR

Introduction

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) protein quality control system ensures the correct folding of transmembrane and secretory proteins before their export from this organelle 1. Accumulation of improperly folded proteins in the ER triggers the unfolded protein response (UPRER) to restore ER homeostasis. This is achieved by enhancing ER-Associated Degradation (ERAD), increasing ER protein folding capacity, decreasing protein translation and inducing a defined gene expression profile (UPRER genes) 2. Although most of these molecular events are clearly established, the mechanism leading to the transcriptional regulation of specific genes under ER stress remains poorly understood.

Here, using as a model the nematode C. elegans, we identify a novel functional partner for p97/CDC-48, an AAA+ ATPase involved ER stress response, in the regulation of ER-stress-associated UPRER gene transcription. C. elegans expresses two p97/CDC-48 homologs, cdc-48.1 and cdc-48.2, which share similar functions in ERAD. While simultaneous silencing of both cdc-48.1 and cdc-48.2 leads to ER stress, UPRER gene activation and lethality 3. Inactivation of either cdc-48.1 or cdc-48.2 is viable but abolishes the transcriptional activation of UPRER genes in response to ER stress 4. Using a C. elegans strain mutant for the p97/CDC-48 homolog cdc-48.2(−/−), we performed a genome-wide RNAi screen to identify proteins involved in the activation of UPRER genes during ER stress. We found that the AAA+ ATPase RUVB-2 is a regulator of the ER stress response by repressing the transcription of select UPRER genes in non-stressed conditions in both C. elegans and human cells. In response to ER stress, RUVB-2 is degraded in a CDC-48-dependent manner, thereby relieving repression of UPRER genes. Altogether, our results identify a novel mechanism controlling gene expression downstream of p97/CDC-48 and unveil a novel function for RUVB-2 and its human homolog Reptin as a key regulator of the transcriptional response to ER stress.

Results and Discussion

A genome-wide screen identifies cdc-48 genetic interactors regulating ER-stress-induced gene expression

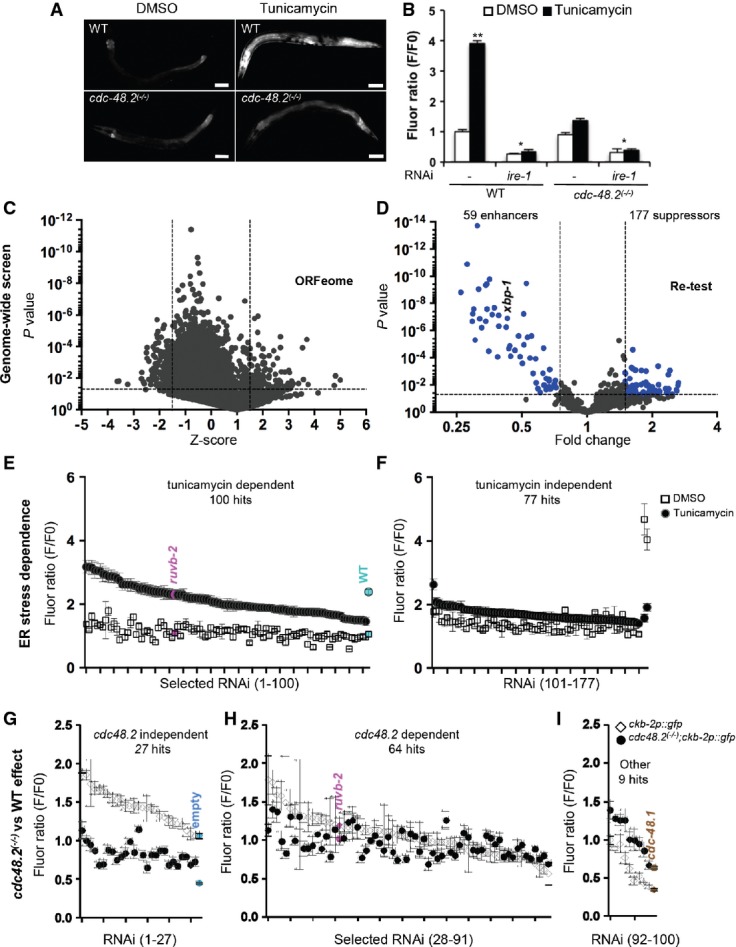

RNAi-mediated knockdown of cdc-48.1 or cdc-48.2 in C. elegans abolishes the ER-stress-induced expression of a set of UPRER genes including ckb-2 4. Using a transcriptional reporter expressing GFP under the control of the ckb-2 promoter, we confirmed the requirement for cdc-48.1 and cdc-48.2 in ER-stress-induced gene transcription (Fig1A). Mutant cdc-48.1(−/−) and cdc-48.2(−/−) worms failed to respond to the ER-stress inducer tunicamycin while ckb-2p::gfp fluorescence was increased more than threefold in wild-type (WT) worms (Fig1B). RNAi inactivation of ire-1, the main sensor of ER stress and mediator of UPRER signaling, resulted in a significant decrease in fluorescence intensity in both ckb-2p::gfp and cdc-48.2(−/−); ckb-2p::gfp worms (Fig1A, Supplementary Table S1). These results confirm that ckb-2p::gfp transcription is IRE1 dependent, as expected of a bona fide UPRER reporter.

Figure 1.

- A cdc-48.2 is required to activate ckb-2p::gfp transcription in response to tunicamycin. Images of adult worms (left) expressing gfp under the control of the ckb-2 gene promoter in WT (upper panels) and in cdc-48.2(−/−) mutants (lower panels) exposed to tunicamycin (5 μg/ml) or DMSO for 16 h. (Scale bar: 50 μm, obj.: 10×).

- B Significant changes in fluorescence intensities were quantified using flow cytometry. L1 larvae (ckb-2p::gfp and cdc-48.2(−/−); ckb-2::pgfp larvae) were fed with bacteria expressing the L4440 empty vector or ire-1RNAi in liquid culture and exposed to tunicamycin (0.5 μg/ml) or DMSO for 16 h. F0 was defined as the fluorescence intensity obtained in ckb-2p::gfp worms fed with the empty vector and treated with DMSO. (Mean ± s.e.m, N + 8, 200 worms/experiment). P-values were calculated using multiple t-test corrected using the Holm–Sidak method **P < 0.001; *P < 0.01.

- C Genome-wide RNAi screen identifies suppressors and enhancers of cdc-48.2(−/−) in ckb-2p::gfp transcription. Volcano plots present results obtained using Caenorhabditis elegansORFeome library.

- D Re-testing of RNAi clones from first round.

- E, F Classification of ER stress dependence of the 177 suppressor RNAi clones able to restore ckb-2p::gfp transcription in cdc-48.2(−/−) mutant background. cdc-48.2(−/−); ckb-2p::gfp synchronized L1 larvae were fed with the dsRNA expressing bacteria in liquid culture, treated with tunicamycin (0.5 μg/ml) or DMSO for 16 h, and fluorescence intensities were measured by flow cytometry. (E) Tunicamycin-dependent RNAi clones were defined as those that significantly increased fluorescence ratio following tunicamycin treatment (Tunicamycin/DMSO F/F0 fold change > 1.5). (F) Tunicamycin-independent RNAi clones were defined as those increasing ckb-2p::gfp fluorescence ratio in both conditions (Tunicamycin/DMSO F/F0 fold change < 1.5, P > 0.05). Fluorescence ratios obtained with ruvb-2RNAi are shown in magenta. Fluorescence ratios obtained with ckb-2p::gfp worms fed with the empty vector and treated with tunicamycin (2.38 ± 0.18) or DMSO (1.05 ± 0.2) are shown in cyan.

- G-I F0 was defined as the fluorescence intensity obtained in cdc-48.2(−/−); ckb-2p::gfp worms fed with the empty vector and treated with tunicamycin or DMSO, respectively. (Mean ± s.e.m, N + 5). Identification of ER-stress-dependent RNAi clones targeting genes involved in the same genetic pathway as cdc-48.2 to increase ckb-2p::gfp transcription. Fluorescence ratio were determined on cdc-48.2(−/−); ckb-2::gfp and ckb-2::gfp worms fed with the suppressor RNAi clones and treated with tunicamycin (0.5 μg/ml) for 16 h. Graphs present the RNAi clones whose effect on ckb-2p::gfp fluorescence was higher ((G), (ckb-2::gfp F/F0/cdc-48.2(−/−); ckb-2::gfp F/F0) fold change > 1.4-fold), similar ((H), (ckb-2::gfp F/F0/cdc-48.2(−/−); ckb-2::gfp F/F0) fold change < 1.4, P > 0.05) or lower ((I), (ckb-2::gfp F/F0/cdc-48.2(−/−); ckb-2::gfp F/F0) fold change < 0.75) in ckb-2p::gfp worms compared to cdc-48.2(−/−); ckb-2p::gfp worms. Fluorescence ratios obtained with ruvb-2RNAi and the two controls empty vector and cdc-48.1 control RNAis are shown in magenta, cyan and brown, respectively. (Mean ± s.e.m, N + 5).

Because p97/CDC-48 is involved in protein degradation 5, we reasoned that it might modulate ER-stress-induced ckb-2p transcription by eliminating a transcriptional repressor. To address this hypothesis, we designed an RNAi suppressor screen to identify genes whose knockdown could restore tunicamycin ckb-2p::gfp activation following ER stress in a cdc-48.2(−/−) mutant background (4; Fig1C). We performed the screen in liquid culture by feeding cdc-48.2(−/−); ckb-2p::gfp synchronized L1 larvae with double-stranded RNA (dsRNA)-expressing E. coli derived from the C. elegans ORFeome library that targets 11,698 open reading frames covering 62% of C. elegans genes 6). We then exposed the worms to a concentration of tunicamycin (0.5 μg/ml for 16 h) leading to maximal ckb-2p::gfp induction in WT worms grown in liquid culture and analyzed them by flow cytometry 7 to measure their length, number and fluorescence intensity. Each RNAi clone was tested in duplicate, and the mean Z-score was calculated. Two-hundred and forty-one RNAi clones synergized with cdc48.2(−/−) to decrease ckb-2p::gfp expression in our primary screen (mean Z-score value less than −1.5, or one of the two independent Z-scores less than −3) (Fig1C). Of these, 59 clones significantly decreased GFP fluorescence below 0.75-fold (P < 0.05) (Fig1D, Supplementary Table S2). One-hundred and seventy-seven RNAi clones instead reproducibly increased (average Z-score >1.5 or one of the two individual Z-scores >3) GFP fluorescence 1.5-fold above the fluorescence intensity measured with cdc-48.2(−/−); ckb-2p::gfp worms fed with an empty vector and treated with tunicamycin (P < 0.05). These were classified as potential suppressors of the cdc48.2(−/−) phenotype.

To discriminate between ER-stress-dependent and ER-stress-independent activation of ckb-2p::gfp transcription, we measured fluorescence intensity in cdc-48.2(−/−); ckb-2p::gfp worms fed with candidate RNAi clones and treated either with tunicamycin or vehicle (DMSO; Fig1E). Seventy-seven RNAi clones showing a similar increase in the fluorescence ratios under both conditions were considered ER-stress independent and not further analyzed (Fig1F, Supplementary Table S3). By contrast, 100 RNAi clones which restored ckb-2p::gfp activation in the cdc48.2(−/−) mutant background specifically under tunicamycin treatment were identified as ER-stress-dependent suppressors of cdc48.2(−/−) (Fig1E, Supplementary Table S4). We next investigated whether the genes targeted by these RNAi clones could activate gene transcription specifically under ER stress independently of cdc-48.2. If a targeted gene acts exclusively in the same genetic pathway as cdc-48.2, then its knockdown by RNAi should not increase ckb-2p::gfp transcription in a WT background, nor have an additive effect with the cdc-48.2(−/−) mutation on ckb-2p::gfp transcription. We quantified and compared ckb-2p::gfp fluorescence intensities in both WT and cdc-48.2(−/−) mutant worms fed with RNAi and exposed to tunicamycin. Twenty-seven RNAi clones increased fluorescence intensities in WT more than in cdc-48.2(−/−) worms (fold change ≥1.4, Fig1G). Nine other clones showed higher fluorescence in mutant worms compared to WT (fold change ≥1.4, Fig1I), similar to cdc-48.1 RNAi. The corresponding 36 genes (27+9) were therefore not considered as strict suppressor of cdc-48.2 and were not further analyzed. We thus identified 64 suppressor RNAi clones that did not show any synthetic enhancement phenotype in cdc-48.2(−/−) relative to WT (fold change < 1.4 and P < 0.05, Fig1H). Taken together, these results identify genes controlling ckb-2p::gfp expression upon ER stress in a CDC-48 dependent fashion and may provide mechanistic insight for the role of CDC-48 in ER-stress-induced gene expression (Fig2A). Among these candidates, the AAA+ ATPase Ruvb2 was of particular interest.

Figure 2.

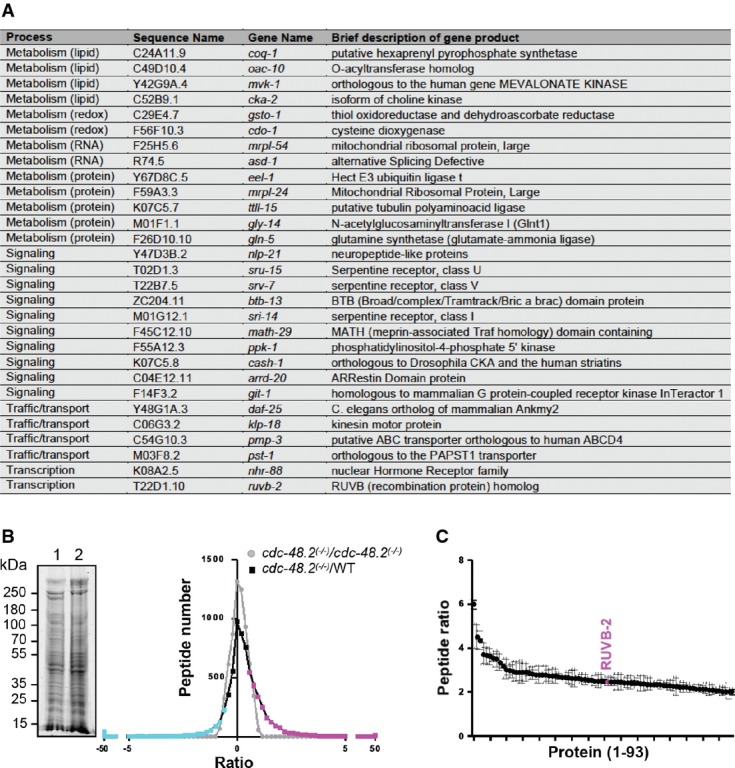

- A List of RNAi clones suppressing the cdc-48.2(−/−) phenotype.

- B Graph representing identified peptide number identified in function of peptide quantity ratio. cdc-48.2(−/−); ckb-2::gfp and ckb-2::gfp synchronized L1 larvae were grown to the L4 stage and exposed to tunicamycin (5 μg/ml) for 16 h on plates. Proteins (60 μg) were separated on a 10% SDS gel. A coomassie blue staining image representative of the SDS gel is shown on the left (1: cdc-48.2(−/−); ckb-2::gfp, 2: ckb-2::gfp). Gel lanes were cut into slices before proteins were in-gel-digested. Peptides were then identified and quantified by label-free LC-MS/MS mass spectrometry. Peptides that were more (magenta) or less (cyan) abundant in the cdc-48.2(−/−); ckb-2::gfp than in ckb-2::gfp worms were defined as those having a ratio above 1.5 or below 0.5, respectively. N + 3.

- C Graph representing peptide quantity ratio ((cdc-48.2(−/−); ckb-2::gfp)/(ckb-2::gfp)) for the 93 proteins that are more abundant in cdc-48.2(−/−) mutant background compared to WT background. (Mean ± s.e.m, N + 3).

To confirm the RNAi screen findings, we conducted a quantitative proteomic analysis to identify proteins whose levels are modified in cdc-48.2(−/−); ckb-2p::gfp worms exposed to tunicamycin. We selected proteins represented by at least two peptides and that had a peptide ratio above 2 or below 0.5 between WT and mutant worms exposed to tunicamycin. Ninety-three proteins increased and 15 proteins decreased in abundance in cdc-48.2(−/−) mutants compared to the WT (Fig2B, Supplementary Table S5). RUVB-2 was the only suppressor identified in our RNAi screen for which an increase in protein abundance could be detected in cdc-48.2(−/−); ckb-2p::gfp compared to ckb-2p::gfp worms (2.5 ± 0.5-fold increase, Fig2C). Because the quantity of ruvb-2 mRNA was not increased (Supplementary Fig S4A) under these conditions, the increased abundance of RUVB-2 in cdc-48.2(−/−) mutants is likely due to attenuation of protein degradation rather than to increased transcription.

Conserved RUVB-2 and CDC-48-dependent regulation of UPRER gene expression

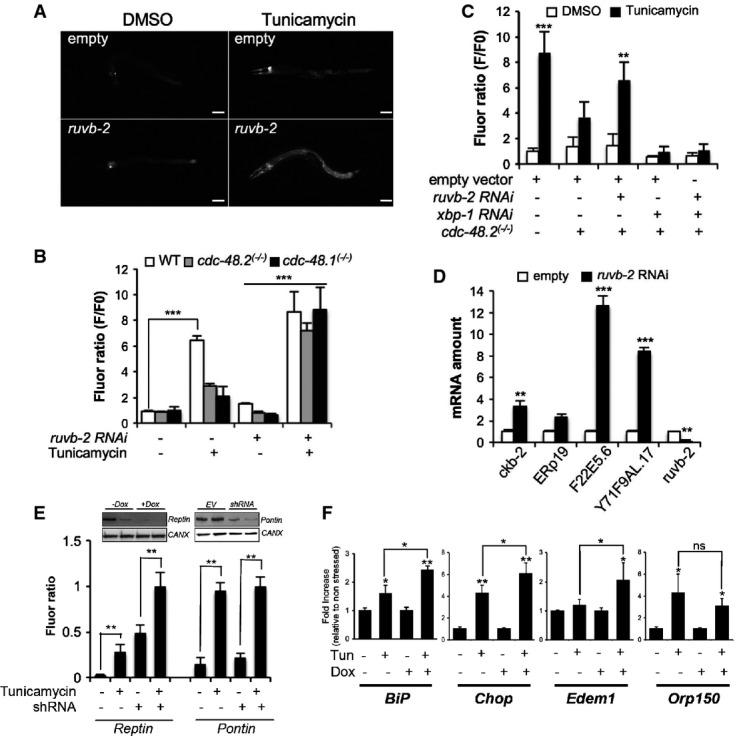

RNAi knockdown of ruvb-2 restored ckb-2p::gfp activation both in cdc-48.2(−/−) and cdc-48.1(−/−) mutant worms exposed to tunicamycin (Fig3A–B). This suggests that, under ER stress, the repressor RUVB-2 is degraded through a CDC-48.1-dependent mechanism to allow full ckb-2p::gfp induction. Moreover, knockdown of xbp-1 reduced ckb-2p::gfp expression in cdc-48.2(−/−); ckb-2p::gfp worms treated with tunicamycin compared to the DMSO-treated ones (Fig3C). Combined RNAi-mediated knock-down of xbp-1 and ruvb-2 decreased ckb-2p::gfp fluorescence to the same level observed using xbp-1 RNAi alone. This suggests that RUVB-2 is degraded through a CDC-48-dependent mechanism in response to tunicamycin, thus allowing XBP-1s to activate ckb-2 expression. Ruvb-2 inactivation also restored the expression of ER homeostasis regulators (CKB-2, F22E5.6, Y71F9AL.17/COPA-1) observed upon ER stress in WT animals 8 in cdc-48.2(−/−) tunicamycin-treated worms (Fig3D and Supplementary Fig S4B). These results suggest that RUVB-2 represses the expression of select UPRER target genes. We next tested whether this function was conserved in human cells. To this end, Huh7 cells transfected with the ER stress response element reporter gene (ERSE::tomato 9) were knocked down for Reptin using stable integration of a doxycycline-inducible short hairpin RNA (shRNA 10) (Fig3E, left). Induction of Reptin shRNA synergized with tunicamycin treatment to activate ERSE::tomato transcription, demonstrating that Reptin can also a repress ER-stress-mediated transcription in human cells. Of note, the silencing of the Reptin homolog Pontin did not affect the transcription of the ERSE::tomato reporter under basal conditions or upon tunicamycin-induced ER stress (Fig3E, right). We next quantified the mRNA amounts of 4 genes whose products are involved in the control of ER homeostasis (BiP, CHOP, EDEM1, ORP150). This revealed that Reptin silencing significantly increased the expression of BiP, CHOP and EDEM1 while did not affect that of ORP150 (Fig3F). Moreover, Reptin overexpression led to the significant repression of select genes (CHOP, EDEM1, ORP150) under basal conditions when compared to control transfected cells (Supplementary Fig S5). Altogether, these results suggest the existence of a conserved role for Reptin in repressing expression of ER stress response genes.

Figure 3.

- A Images of cdc-48.2(−/−); ckb-2::gfp adult worms fed with either the L4440 empty vector (upper panel) or ruvb-2RNAi (lower panel) and treated with tunicamycin (5 μg/ml) or DMSO for 16 h on NGM agar plates. (Scale bar: 50 μm, obj: 10×).

- B Fluorescence was quantified by flow cytometry on ckb-2::gfp,cdc-48.1(−/−); ckb-2::gfp and cdc-48.2(−/−); ckb-2::gfp worms fed with ruvb-2RNAi or empty vector starting at the L1 stage in liquid culture and exposed to tunicamycin (0.5 μg/ml) or DMSO for 16 h. Fluorescence (F) was normalized to the basal fluorescence obtained with empty vector and DMSO in the WT background (F0). (Mean ± SD,N + 5) ***P < 0.001.

- C Fluorescence (F) was quantified by flow cytometry on ckb-2::gfp and cdc-48.2(−/−); ckb-2::gfp worms fed with either ruvb-2 and empty vector (1:1), xbp-1 and empty vector (1:1), ruvb-2 and xbp-1RNAi (1:1), or empty vector alone and treated with tunicamycin (0.5 μg/ml) or DMSO for 16 h. Fluorescence (F) was normalized to the basal fluorescence obtained with the empty vector and DMSO in the WT background (F0). (Mean ± s.e.m, N + 3). P-values were calculated using multiple t-test corrected using the Holm-Sidak method. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

- D RT–qPCR quantification of the relative expression levels of 3 endogenous ER homeostasis genes (ERp19, F22E5.6, Y71F9AL.17/COPA-1), Ckb-2 and Ruvb-2 following tunicamycin treatment in cdc-48.2(−/−) worms subjected or not to ruvb-2RNAi. Bars represent the mean of three biological replicates. (Mean ± s.e.m, N + 3) **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

- E Fluorescence was quantified in HuH7 cells expressing the ERSE::Tomato construct and either the Reptin shRNA induced with doxycycline (left) or the Pontin shRNA (transient, right). Cells were exposed to tunicamycin (5 μg/ml) for 4 h prior to measurement. Data are presented as mean ± SD of three independent experiments. Note that Reptin levels were decreased upon Tunicamycin treatment (see also Fig4A). **P < 0.01.

- F RT–qPCR analysis of four ER homeostasis control genes under basal conditions or upon tunicamycin treatment (5 μg/ml, 16 h) in HuH7 cells subjected or not to doxycycline-induced Reptin silencing. Data are presented as mean ± SD of three independent biological triplicates. (Mean ± s.e.m, N + 3) P-value was calculated using multiple t-test corrected using the Holm-Sidak method. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Post-translational control of Reptin expression by p97/CDC-48 impacts on ER stress response in human cells

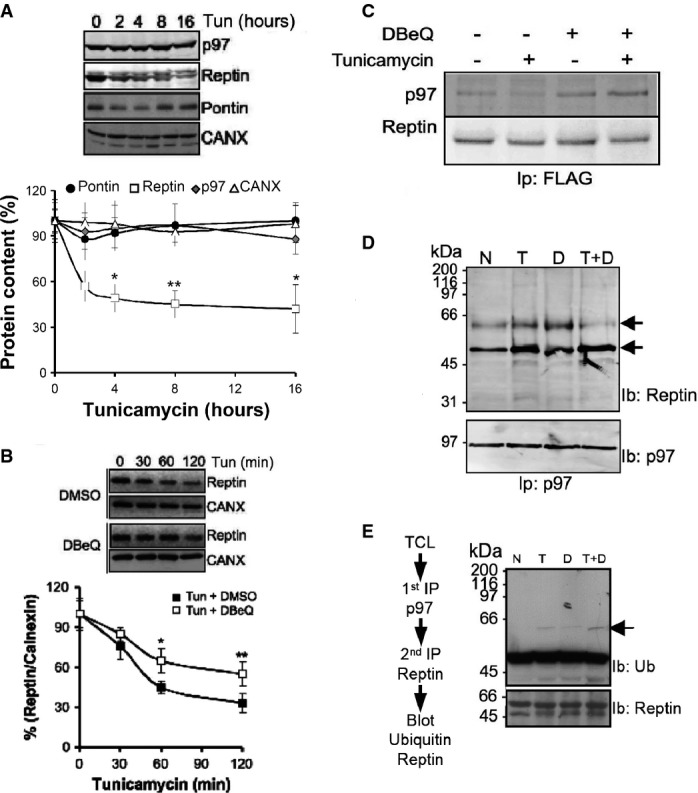

Further, we examined whether p97/CDC-48 could also acted by triggering the degradation of Reptin in response to ER stress as observed in C. elegans (Fig2). Reptin protein levels were significantly decreased upon tunicamycin treatment, whereas p97/CDC-48, Pontin and Calnexin protein expression remained unaffected (Fig4A). Conversely, addition of the p97/CDC-48 inhibitor DBeQ stabilized Reptin levels under ER stress (Fig4B). We then tested whether p97 and Reptin interacted physically using co-immunoprecipitation. These results were confirmed by determining Reptin's half-life upon stress (Supplementary Table S6), and the values obtained under basal conditions were in the range of those determined in S. cerevisiae or S. pombe 11. Reptin immunoprecipitates contained p97/CDC-48, and the interaction was modulated by tunicamycin-induced ER stress, DBeQ or both (Fig4C). Interestingly, when the reverse experiment was carried out, Reptin was found in the p97/CDC-48 immunoprecipitate as well as a slower migrating Reptin immunoreactive species (Fig4D, arrow). Sequential immunoprecipitation with p97/CDC-48 and Reptin antibodies suggested that the latter corresponds to an ubiquitylated form of Reptin (Fig4E). Hence, p97/CDC-48 might control Reptin levels through an ubiquitin-dependent mechanism.

Figure 4.

- A Reptin, Pontin, calnexin and quantification by immunoblot. Values are expressed as a percentage of the initial protein abundance in total HuH7 cell lysate before addition of tunicamycin (5 μg/ml), (Mean ± SD,N + 5). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

- B Immunoblot analysis of Reptin in total protein extracts from HuH7 cells exposed to tunicamycin (5 μg/ml) for 0–2 h. Protein levels were normalized to Calnexin (mean ± SD,N + 3). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

- C HuH7 cells expressing FLAG tagged Reptin were treated either with the p97/CDC-48 inhibitor DBeQ (20 μM, D), the ER stress inducer tunicamycin (2 μg/ml; T) or both for 4 h. FLAG tagged Reptin was immunoprecipitated from total protein extracts using anti-FLAG antibodies, and p97/CDC-48 association was analyzed by immunoblot.

- D HuH7 cells were treated either with DBeQ (20 μM, D), (2 μg/ml; T) or both for 4 h. P97/CDC-48 was immunoprecipitated from total protein extracts using an antibody specific for p97/CDC-48, and reptin association was analyzed by immunoblotting.

- F HuH7 cells were treated either with DBeQ (20 μM, D), tunicamycin (2 μg/ml; T) or both for 4 h. P97/CDC-48 was immunoprecipitated from total protein extracts using anti-p97/CDC-48 antibodies. P97/CDC-48 immunoprecipitate was disrupted with 50 μl of 1% SDS and heated at 95°C for 5 min. Beads were removed and the supernatant quenched with PBS containing 1% TX-100. Reptin was then sequentially immunoprecipitated and the resulting immunoprecipitate immunoblotted with anti-Ubiquitin or anti-Reptin antibodies.

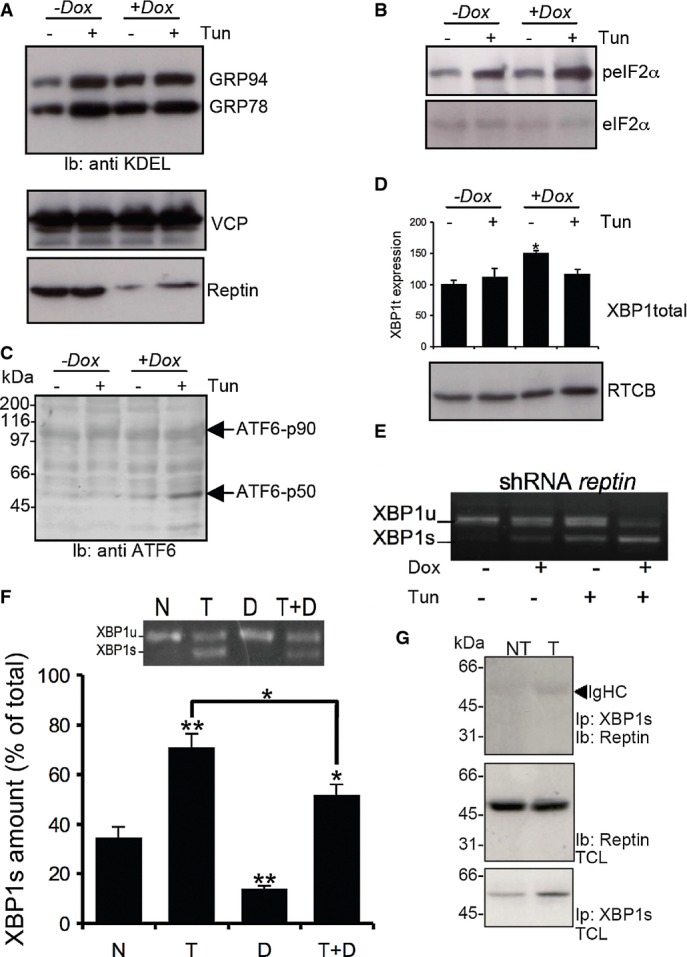

XBP1 mRNA splicing and ATF6 activation are partly regulated by a p97/reptin signaling axis

To follow up on the role of Reptin degradation upon ER stress in the expression of ER stress genes, we sought to test whether artificial modulation of Reptin expression also impacted the activation of the three UPR signaling arms. Reptin silencing slightly increased the expression of the ER-stress-upregulated chaperones GRP78 and GRP94, which are canonical targets of ATF6 and XBP1s signaling, under basal conditions (Fig5A), but did not affect tunicamycin-induced phosphorylation of eIF2α (Fig5B). ATF6 cleavage activation was increased after Reptin silencing in HuH7 cells (Fig5C). In accordance with this observation, reptin silencing also enhanced the expression of XBP1u mRNA under basal conditions, as could be expected since XBP1u is a target gene of ATF6 (Fig5D). Moreover, this occurred without affecting the expression levels of the newly discovered XBP1 mRNA ligase RtcB 12 (Fig5D). XBP1 mRNA splicing was also increased when Reptin was silenced both in basal conditions and ER stress (Fig5E). Conversely, DBeQ-mediated p97/CDC-48 inhibition (Fig5F) or siRNA-mediated p97/CDC-48 silencing (Supplementary Fig S6) and the subsequent stabilization of Reptin led to reduced XBP1 mRNA splicing. Hence, partial stabilization of Reptin has a major impact on XBP1 mRNA splicing, which in turn impacts dramatically on the expression of various UPRER genes. However, we could not detect an interaction between Reptin and XBP1s protein (Fig5G). Altogether, these results might indicate that Reptin is degraded through ubiquitin and p97/CDC-48-dependent mechanisms under ER stress and further support the role of Reptin in the control of select UPRER genes through repression of XBP1 mRNA splicing and of ATF6 activation.

Figure 5.

- A GRP78 and GRP94 expression was detected using anti-KDEL antibodies (top blot) in HuH7 cells treated or not with tunicamycin and/or doxycycline (Dox) to induce reptin silencing (bottom blot). Expression of p97 was also monitored (middle blot).

- B eIF2α phosphorylation was monitored using specific antibodies (top blot) and reported to the total expression (bottom blot) in HuH7 cells treated or not with tunicamycin and/or doxycycline (Dox).

- C ATF6 activation was monitored in the same experimental conditions using antibodies against the N-terminal domain of ATF6.

- D Expression of unspliced XBP1 mRNA as determined by RT–PCR and expression of the XBP1s ligase RTCB as determined by immunoblot using anti-RTCB antibodies in HuH7 cells treated or not with tunicamycin and/or doxycycline (Dox).

- E XBP-1 mRNA splicing as determined by RT–PCR under basal conditions or upon tunicamycin treatment (5 μg/ml for 16 h) in HuH7 cells subjected or not to doxycycline-induced Reptin silencing. Three independent experiments were performed, and a representative image is shown.

- F HuH7 cells were treated either with DBeQ (20 μM, D), tunicamycin (2 μg/ml; T) or both for 4 h. XBP-1 mRNA splicing was determined by RT–PCR (Mean ± SD,N + 3). P-values were calculated using multiple t-test corrected using the Holm-Sidak method. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

- G HuH7 cells were treated with tunicamycin (2 μg/ml; T) for 1 h. XBP1s was immunoprecipitated, and the complex was immunoblotted with anti-Reptin antibodies (top blot). Total cell lysate (TCL) was immunoblotted with anti-Reptin (middle blot) or anti-XBP1s (bottom blot).

In the present work, we have uncovered a novel regulatory mechanism of UPRER genes expression in response to ER stress conserved throughout metazoan evolution involving two AAA+ ATPases, RUVB-2 (or Reptin) and CDC-48 (or p97). In this model, RUVB-2, which mostly localizes to the cytoplasm and the nucleus, plays an important role in the regulation of XBP1 mRNA splicing by a yet unknown mechanism. Upon ER stress, RUVB-2 is degraded through an ubiquitin and p97/CDC-48-dependent mechanism, thereby allowing the ER-stress-specific transcription factors ATF6 and XBP-1 to activate the transcription of UPRER genes. Beyond unravelling a novel UPRER regulatory network, our data point toward the putative role of Reptin in non-conventional mRNA splicing. Our findings suggest that p97/CDC-48-induced degradation of target proteins plays an important role in the ER homeostasis control both, in the cytoplasm, to influence ERAD and to modulate UPRER gene transcription 13.

Materials and Methods

RNAi screen

The RNAi feeding screen was performed in liquid culture using EM2 animals and carried out as previously described with some modifications 4. RNAi clones from the Worm ORFeome version 1.1 library 6 were grown overnight at 37°C in 96-well plates. Each RNAi plate included a positive control (Y37D8A.10 encoding for a signal peptidase identified in a preliminary screen or BC14636 worms fed with the L4440 empty vector) and a negative control (gfp RNAi). RNAi expression was induced with 1 mM IPTG for 1 h before bacteria were added to the L1 larvae. Adult worms were bleached,and the obtained L1 larvae (200) were added to each well of 96-well plates along with the induced bacteria and S-Medium, 50 μg/ml ampicillin, 1 mM IPTG buffer with a final well volume of 150 μl. The 96-well plates were incubated at 20°C with shaking. Forty-eight hours later, ER stress was induced by tunicamycin (0.5 μg/ml) for 16 h, and measurements were taken using the COPAS Biosort flow cytometer (Union Biometrica, Holliston, MA, USA). Experiments for each 96-well plate from the RNAi library were performed in duplicate. Fluorescence average value for each plate was calculated and used to calculate the individual RNAi fold change. Plates showing no fluorescence induction in the positive control, no fluorescence decrease in negative control, or a high fluorescence mean were discarded and retested.

COPAS measurements

The COPAS biosort analyzer was purchased from Union Biometrica (Holliston, MA, USA). Photomultiplicator tube control (PMT1) was set up at 600 so that the green fluorescence emission was not saturated in BC14636 worms exposed to tunicamycin (maximum signal) and still detectable in EM2 worms exposed to gfp RNAi (minimum signal). Plates were read through a ReFLx module. Raw data extracted from COPAS included worm axial length (time of flight), worm number (extinction) and fluorescence (green fluorescence emission). Raw data were processed as previously described 14 and used for quantitative analyses.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. R. Pedeux for help with the post-translational modifications of reptin, E Attebi and K Rebora for help with C. elegans screens, Drs E. Snapp and F. Schoenen for the ERSE::Tomato construct and DBeC, respectively, Dr. S. Mitani for the cdc-48.1(tm544) and cdc-48.2(tm659) strains. This work was funded by grants from “Institut National du Cancer” to EC and JR. EM was funded by a scolarship from Association Française contre les Myopathies.

Author contributions

EM, AAR, ST, KB, EC, JWD and NPL performed experiments. LG and DD developed the bioinformatics tools. MB supervised the proteomics analysis. JR and FP provided tools. EM, DD and EC coordinated the study. EM, MFZ, DD and EC wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supporting Information

Supplementary Figures

Supplementary Table S1

Supplementary Table S2

Supplementary Table S3

Supplementary Table S4

Supplementary Table S5

Supplementary Table S6

Review Process File

References

- Ellgaard L, Helenius A. Quality control in the endoplasmic reticulum. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:181–191. doi: 10.1038/nrm1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetz C, Chevet E, Harding HP. Targeting the unfolded protein response in disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12:703–719. doi: 10.1038/nrd3976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouysset J, Kähler C, Hoppe T. A conserved role of Caenorhabditis elegans CDC-48 in ER-associated protein degradation. J Struct Biol. 2006;156:41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caruso ME, Jenna S, Bouchecareilh M, Baillie DL, Boismenu D, Halawani D, Latterich M, Chevet E. GTPase-mediated regulation of the unfolded protein response in Caenorhabditis elegans is dependent on the AAA+ ATPase CDC-48. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:4261–4274. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02252-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantuma NP, Hoppe T. Growing sphere of influence: Cdc48/p97 orchestrates ubiquitin-dependent extraction from chromatin. Trends Cell Biol. 2012;22:483–491. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reboul J, Vaglio P, Rual JF, Lamesch P, Martinez M, Armstrong CM, Li S, Jacotot L, Bertin N, Janky R, et al. Caenorhabditis elegans ORFeome version 1.1: experimental verification of the genome annotation and resource for proteome-scale protein expression. Nat Genet. 2003;34:35–41. doi: 10.1038/ng1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squiban B, Belougne J, Ewbank J, Zugasti O. Quantitative and automated high-throughput genome-wide RNAi screens in C. elegans. J Vis Exp. 2012;pii:3448. doi: 10.3791/3448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen X, Ellis RE, Sakaki K, Kaufman RJ. Genetic interactions due to constitutive and inducible gene regulation mediated by the unfolded protein response in C. elegans. PLoS Genet. 2005;1:e37. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lajoie P, Snapp EL. Changes in BiP availability reveal hypersensitivity to acute endoplasmic reticulum stress in cells expressing mutant huntingtin. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:3332–3343. doi: 10.1242/jcs.087510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haurie V, Ménard L, Nicou A, Touriol C, Metzler P, Fernandez J, Taras D, Lestienne P, Balabaud C, Bioulac-Sage P, et al. Adenosine triphosphatase pontin is overexpressed in hepatocellular carcinoma and coregulated with reptin through a new posttranslational mechanism. Hepatology. 2009;50:1871–1883. doi: 10.1002/hep.23215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiano R, Nagaraj N, Fröhlich F, Walther TC. Global Proteome Turnover Analyses of the Yeasts S. cerevisiae and S. pombe. Cell Rep. 2014;9:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.10.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosmaczewski SG, Edwards TJ, Han SM, Eckwahl MJ, Meyer BI, Peach S, Hesselberth JR, Wolin SL, Hammarlund M. The RtcB RNA ligase is an essential component of the metazoan unfolded protein response. EMBO Rep. 2014;15:1278–1285. doi: 10.15252/embr.201439531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fessart D, Marza E, Taouji S, Delom F, Chevet E. P97/CDC-48: Proteostasis control in tumor cell biology. Cancer Lett. 2013;337:26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupuy D, Bertin N, Hidalgo CA, Venkatesan K, Tu D, Lee D, Rosenberg J, Svrzikapa N, Blanc A, Carnec A, et al. Genome-scale analysis of in vivo spatiotemporal promoter activity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:663–668. doi: 10.1038/nbt1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures

Supplementary Table S1

Supplementary Table S2

Supplementary Table S3

Supplementary Table S4

Supplementary Table S5

Supplementary Table S6

Review Process File