Abstract

IGF1R is emerging as an important gene in the pathogenesis of many solid and haematological cancers and its over-expression has been reported as frequently associated with aggressive disease and chemotherapy resistance. In this study we performed an investigation of the role of IGF1R expression in a large and representative prospective series of 217 chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) patients enrolled in the multicentre O-CLL1 protocol (clinicaltrial.gov #NCT00917540). High IGF1R gene expression was significantly associated with IGHV unmutated (IGHV-UM) status (p<0.0001), high CD38 expression (p<0.0001), trisomy 12 (p<0.0001), and del(11)(q23) (p=0.014). Interestingly, higher IGF1R expression (p=0.002) characterized patients with NOTCH1 mutation (c.7541_7542delCT), identified in 15.5% of cases of our series by next generation sequencing and ARMS-PCR. Furthermore, IGF1R expression has been proven as an independent prognostic factor associated with time to first treatment in our CLL prospective cohort. These data suggest that IGF1R may play an important role in CLL biology, in particular in aggressive CLL clones characterized by IGHV-UM, trisomy 12 and NOTCH1 mutation.

Introduction

Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) is a common lymphoproliferative disorder characterized by heterogeneous clinical course. During recent years a number of prognostic markers have been proposed in order to distinguish between aggressive and indolent disease [1–3]. The mutational status of the immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region (IGHV) represents one of the most important prognostic markers in CLL and defines two disease subgroups: the first, characterized by the absence of IGHV somatic mutation (IGHV-UM) in CLL cells, is associated with the worst clinical course and outcome; the second presents IGHV somatic mutations (IGHV-M) and has a more favorable prognosis and outcome [4,5]. However, a significant fraction of IGHV-M patients also progresses and requires treatment, a finding that prompts the identification of novel putative clinical and biological markers able to stratify progression risk among these patients.

Insulin Growth Factor 1 receptor (IGF1R) is emerging as an important gene involved in many solid and haematological cancers. Higher expression of the gene has been associated with more aggressive disease and with pharmacological resistance [6]. Specifically the IGF1R-IGF1/2 interaction is involved in the constitutive activation of many important intracellular cell signalling pathways such as RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK kinases that stimulate cellular proliferation, or the phosphoinositide-3 kinase (PI3K)-Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway that predominantly mediates cell survival. Recently IGF1R was reported to be correlated with the NOTCH1 signalling pathway in T-lymphoblastic leukemia where NOTCH1 activating mutations occur in more than half of patients [7]. In addition, the IGF1R was recently tested as novel therapeutic target in solid malignancies and in multiple myeloma where IGF1R inhibitors appear to overcome bortezomib resistance in the malignant plasma cell [8,9].

Although it has been described that IGF1R is heterogeneously expressed in CLL [10], its role in the disease remains to be fully elucidated. Recently it was shown that IGF1R was generally over-expressed in CLL compared to healthy B-cells, and was implicated in the activation of the PI3K/Akt and MAPK pathways; notably, distinct CLL groups [i.e del(11)(q13), del(17)(p13) and trisomy 12 patients] were found to be associated with a significant higher IGF1R expression compared to other patients [11].

Here we investigate the relevance of IGF1R mRNA expression in a large and representative prospective series of Binet stage A CLL patients. In particular, we addressed its possible correlations with biological, molecular and clinical outcome.

Materials and Methods

Patients

Newly diagnosed Binet stage A CLL patients from several Italian Institutions were prospectively enrolled into the O-CLL1 protocol (clinicaltrial.gov #NCT00917540). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki and the study was approved by the local Ethics Review Committee (Comitato Etico Provinciale, Modena, Italy). Diagnosis was confirmed by the biological review committee according to flow cytometry analysis centralized at the National Cancer Institute (IST) as previously described [12]. Treatment was decided uniformly in all participating centres based on documented progressive and symptomatic disease according to NCI-Working Group guidelines [2]. To date, 463 Binet A CLL patients have been selected according to the inclusion criteria of the protocol. Two hundred and seventeen CLL patients for whom RNA material was available were analysed by means of GeneChip Gene 1.0 ST Array (Affymetrix) as previously described [12] and IGF1R gene expression data have been inferred for each case. Gene expression data has been deposited in the National Centre for Biotechnology Information’s Gene Expression Omnibus database http://www.ncbi.nlm.mih.gov/geo and are accessible through series accession number GSE51529. Biological and molecular analyses were performed in peripheral CD19+ B-cell samples collected from all patients within 12 months after diagnosis as previously described [13,14].

CD38 expression was investigated as previously described and a 20% cut-off was chosen to discriminate positive from negative patients [15]. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analyses of the most common cytogenetic deletions, IGHV mutational status and stereotyped HCDR3 analysis were performed as previously described [16,17]. NOTCH1 c.7541_7542delCT mutation was tested in 199 cases by next generation sequencing using the Roche 454 technology and subsequently validated by Amplification Refractory Mutation System (ARMS)-PCR as previously described [18].

According to the 1996 NCI guidelines [19], 162 (74.7%), 40 (18.4%) and 15 (6.9%) patients were classified as Rai 0, Rai I and Rai II, respectively. However, based on the more recent International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia (IWCLL) diagnostic criteria [2], 45 (20.7%) Rai stage 0 patients having less than 5.0x109/L circulating monoclonal B lymphocytes were reclassified as clinical monoclonal B-lymphocytosis (cMBL). Patients’ clinical and biological profiles are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Clinical and biological features of patients enrolled in the O-CLL1 protocol and investigated by gene expression profiling.

| All pts (217) | MBL (45) | CLL (172) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median Monoclonal Lymphocytes | 7789 × 106/L | 3568 × 106/L | 9152 × 106/L |

| CD38>20% | 49/217 (26%) | 12/45 (28%) | 50/172 (29%) |

| IGHV-UM | 84/216 (39%) | 16/45 (35%) | 68/172 (39.5%) |

| Normal Cytogenetic | 79 (36.4%) | 14/45 (31%) | 65/172 (37%) |

| del(13)(q14)* | 88 (40.6%) | 17/45 (37%) | 70/172 (41%) |

| Trisomy 12 | 28 (12.9%) | 13/45 (29%) | 15/172 (9%) |

| del(11)(q23) | 16 (7.4%) | 1/45 (2.2%) | 16/172 (9.2%) |

| del(17)(p13) | 6 (2.7%) | 0/45 (0%) | 6/172 ( |

| NOTCH1 mutation | 31/199 (15.5%) | 8/38 (19%) | 23/161 |

*As sole genomic aberrations

Real-Time Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction

IGF1R gene expression levels were analysed in purified CLL CD19+ cells by means of quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (Q-RT-PCR) assay. Total RNA was converted to cDNA using M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). Inventoried TaqMan Gene Expression Assay (Hs00609566_m1) and the TaqMan Fast Universal Master Mix were used according to manufacturer’s instructions (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). 18S TaqMan Gene Expression Control (Hs99999901_s1) (Applied Biosystems) was used as the internal control. The measurement of transcript expression was performed using the Applied Biosystems StepONE Real-Time PCR System. All the samples were run in duplicate. Data were expressed as 2-ΔCt (Applied User Bulletin No. 2).

Statistical Analysis

All contingency analyses were performed by Fisher’s exact test. Quantitative variables were compared using the Mann-Whitney test. Time to First Treatment (TTFT) was defined as time from diagnosis to first line treatment. Cox proportional hazards model was used in the global test function of R software (under 100,000 permutation) to test the positive or negative association between the IGF1R expression levels (as covariate, assumed as continuous variable) and clinical outcome (as response variable, in terms of TTFT). Kaplan-Meier method was used for TTFT curve estimation. Cox proportional hazard model was used for multivariate analysis. P<0.05 was considered significant for all statistical calculations. All the analyses were performed using appropriate functions in R software (www.r-project.org).

Results

We assessed the expression levels of the IGF1R gene in 217 cases included in a prospective cohort of Binet-A CLL patients. IGF1R expression showed a heterogeneous distribution, but no difference was found between cMBL and other CLLs or Rai 0 patients (data not shown). The levels of IGF1R transcripts were also validated by means of Q-RT-PCR in all samples for which RNA was available (61 cases), and showed very good concordance with microarray data (Pearson correlation, r = 0.82) (S1 Fig.).

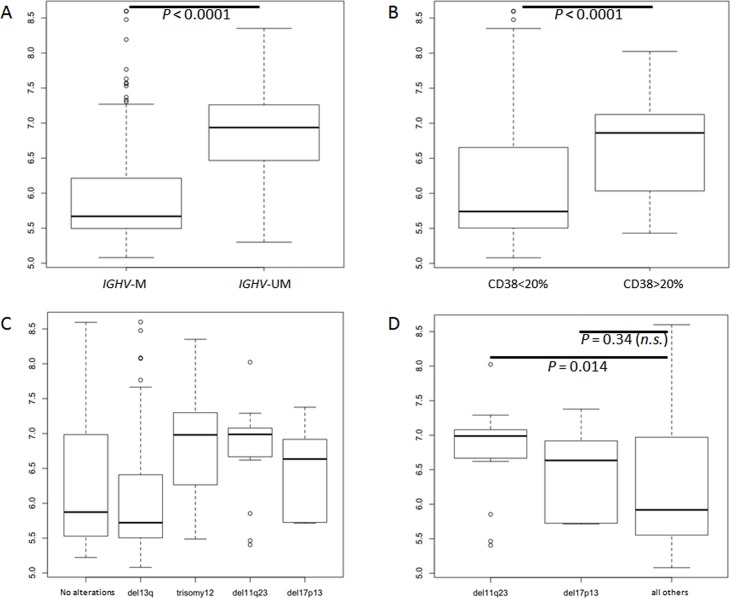

Interestingly among 217 tested patients, IGHV-UM cases were characterized by significantly higher IGF1R expression compared to IGHV-M cases (p<0.0001) (Fig. 1A). This difference was confirmed also if cMBL and CLL patients were considered separately (p = 0.004 and p<0.0001, respectively). Stereotyped HCDR3 was identified in 70 cases (32%) (S1 Table), mainly characterized by IGHV-UM configuration (p<0.0001). Patients with stereotyped HCDR3 sequences showed greater IGF1R expression compared to non-stereotyped HCDR3 (p = 0.001); however, this could in all likelihood be related to the higher frequency of IGHV-UM among stereotyped HCDR patients [45/70; 64%]. Among most frequent stereotyped subset we observed a significant IGF1R overexpression among subset #1, #7, #8 and #10. These last two stereotyped subsets were known to be strictly associated with IGHV-UM, IGHV4–39 utilization and trisomy 12. Of note, subset #4 patients (known to exhibit an indolent clinical course, unique IGHV-M and IGHV4–34 utilization and distinct biological profile [17,20]) were characterized by lower IGF1R expression in all but one (1/10). This patient was the only one who progressed and required treatment among subset #4 subtype. Remarkably, IGF1R expression differed significantly between subset #4 patients and IGHV-M patients (p<0.0001 and p = 0.03 respectively) (S2 Fig.).

Fig 1. Boxplot of IGF1R expression (217 pts) in: A) IGHV-M vs IGHV-UM; B) CD38<20% vs CD38>20%; C) Most common cytogenetic aberrations evaluated by FISH; D) unfavorable cytogenetic deletions (del11q23 and del17p13) vs other patients (favorable/intermediate FISH).

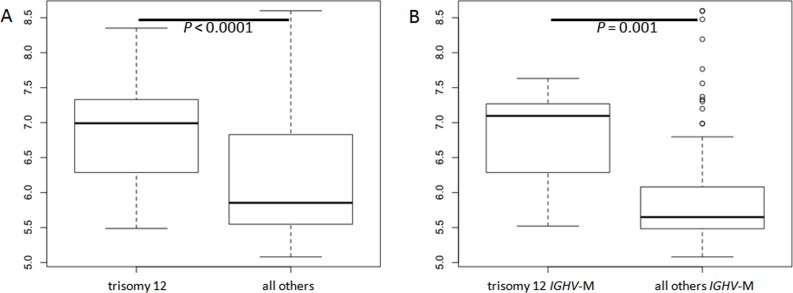

Patients with CD38 positive expression were generally characterized by higher IGF1R expression in almost all cases (p<0.0001) (Fig. 1B). This significant association was confirmed also if 30% was considered as CD38 positivity cut-off (data not shown). Higher IGF1R expression was also associated with unfavorable cytogenetic deletion [i.e. del(11)(q23) and del(17)(p13)], particularly with del(11)(q23) (p = 0.014) (Fig. 1C-D). The association between unfavorable cytogenetic deletions and IGF1R expression was not tested among cMBL due to the lower prevalence of those aberrations in that subgroup of patients. However, cases with del(13)(q14) as unique lesion, were characterized by the lowest IGF1R gene levels considering either all patients (Fig. 1C) and cMBL or CLL separately (p = 0.0004 and p = 0.001, respectively). On the contrary, among the most common cytogenetic aberrations, trisomy 12 showed stronger IGF1R expression compared with the other patients (p<0.0001) (Fig. 2A). IGF1R was highly expressed in almost all patients with trisomy 12 and this association was independent both from cMBL/CLL classification and from IGHV mutational status. In fact considering only IGHV-M patients, the presence of trisomy 12 was associated with a significantly higher IGF1R expression compared to the others (p = 0.001) (Fig. 2B).

Fig 2. Boxplot of IGF1R expression in: A) Trisomy 12 vs no trisomy 12 patients; and B) Trisomy 12 vs no trisomy 12 considering only IGHV-M patients.

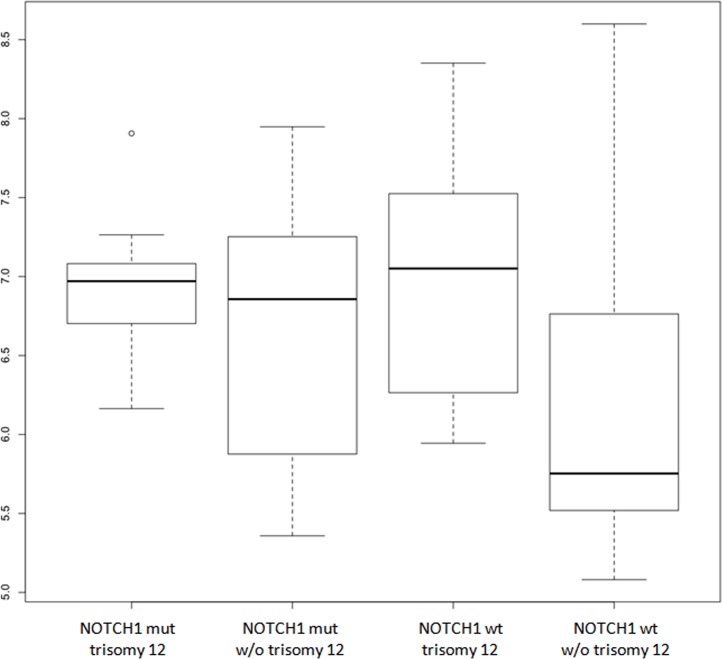

NOTCH1 c.7541_7542delCT mutation was previously investigated by next generation sequencing Roche 454 technology in 199 (91.7%) patients included in the present study [18]. We considered as mutated only those patients (31 cases; 15.5%) in whom the presence of the dinucleotide deletion was confirmed by ARMS-PCR [18]. In our present series, NOTCH1 mutation was confirmed to be strongly associated with trisomy 12, IGHV4–39 gene usage and with shorter TTFT in univariate analysis, whereas no difference in NOTCH1 mutation prevalence was observed comparing cMBL, with CLL or Rai 0 patients (data not shown). Interestingly, patients with NOTCH1 mutation showed a greater IGF1R expression compared with wild type cases (p = 0.002). In addition, high IGF1R expression was not significantly different comparing patients with low and high NOTCH1 mutation burden (data not shown). IGF1R was significantly higher in NOTCH1 mutated patients, either with or without trisomy 12, and in NOTCH1 wt patients with trisomy 12, than in NOTCH1 wt cases without trisomy12 patients (p = 0.0035, p = 0.0031 and p = 0.0002 respectively); no differences in IGF1R expression levels were observed comparing any of the NOTCH1 wt without trisomy 12 counterpart groups (Fig. 3). The correlation between NOTCH1 and IGF1R was also confirmed considering CLL patients only (p = 0.001), conversely, among cMBL the association between IGF1R expression and NOTCH1 mutation did not reach statistical significance, although a partial trend was demonstrated (data not shown).

Fig 3. Boxplot of IGF1R expression in patients stratified according to trisomy 12 and NOTCH1 mutation (mut: mutation; wt: wild-type; w/o: without).

IGF1R was significant higher among the NOTCH1 mut/trisomy12, NOTCH1 mut/NOtrisomy12 and NOTCH1,wd/trisomy12 compared to other patients (p = 0.0035, p = 0.0031 and p = 0.0002 respectively).

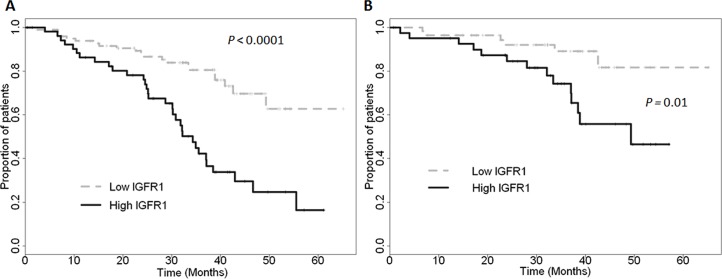

Finally, in CLL patients (cMBL not included), increased IGF1R expression level was strongly associated with aggressive clinical course and shorter TTFT (Fig. 4A).

Fig 4. Kaplan-Meier estimated curves of time to first treatment according to IGF1R expression considering all CLL patients (A) and only IGHV-M patients (B).

Interestingly, IGF1R expression was also correlated with disease aggressiveness among IGHV-M patients (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, none of the biological prognostic factors (i.e CD38, ZAP-70, FISH) were able to predict clinical outcome in this group. Cox’s proportional hazard model built including the most important biological variables revealed that IGF1R expression represented an independent prognostic factor of TTFT in early stage CLL considering either all CLL patients (Table 2) or only IGHV-M (Table 3). Among cMBL, IGF1R did not show a significant association with TTFT.

Table 2. Cox multivariate analysis results considering only CLL patients.

| Covariate | p | HR | 95% CI of HR |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD38 > 20% | 0.1037 | 1.6591 | 0.9045 to 3.0434 |

| del(11)(q23) and del(17)(p13) | 0.0783 | 1.8636 | 0.9353 to 3.7132 |

| IGF1R expression | 0.0258 | 1.0033 | 1.0004 to 1.0062 |

| IGHV mutational status | 0.0128 | 2.3390 | 1.2019 to 4.5519 |

HR: hazard ratio. CI: confidence interval.

Table 3. Cox multivariate analysis results considering only IGHV-M CLL patients.

| Covariate | p | HR | 95% CI of HR |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD38 > 20% | 0.070 | 1.3253 | 0,3075 to 5,7119 |

| del(11)(q23) and del(17)(p13) | 0.1446 | 4.5572 | 0,6002 to 34,5990 |

| IGF1R expression | 0.0094 | 1.0043 | 1,0011 to 1,0075 |

HR: hazard ratio. CI: confidence interval.

Discussion

IGF1R gene is known to regulate normal cell growth and contribute to transformation and proliferation of malignant cells in many cell contexts [6]. This gene has been reported to play an important role in haematological malignancies such as multiple myeloma, mantle cell lymphoma and T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (T-ALL) [7–9,21]. IGF1R was associated also with favorable prognosis in breast cancer, non small cell lung cancer, soft tissue sarcoma and classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma [22–27].

In CLL, it was recently reported that IGF1R is involved in the activation of phosphorylation cascades such as Ras/Raf/MAPK and PI3K-Akt [28].These pathways are emerging as important survival and proliferation signals in CLL and represent an attractive target of novel drugs (i.e ibrutinib and idelasilib) [29–31]. In concordance with a previous study [11], we report the strong association of IGF1R with unfavorable/intermediate cytogenetic aberrations, mainly trisomy 12. This association seemed independent of IGHV-UM, NOTCH1 mutation or cMBL status. Based on this data IGF1R could represent a potential novel candidate for specific targeted therapy in this cluster of patients.

Our data showed a strong association between IGF1R up-regulation and other unfavorable biological features such as IGHV-UM and CD38 expression, differently from what reported by Yaktapour et al [11]. In agreement with these biological associations, high IGF1R expression was independently correlated with shorter TTFT among CLL patients and this association retained its significance also considering only IGHV-M cases. Interestingly IGF1R did not showed a unique association with the most common unfavorable prognostic factors, but its high expression emerged both within trisomy 12 patients, known to have a intermediate clinical course, and IGHV-M cases or other apparently favorable subgroups (i.e del13q14 as single lesion) [3–5]. In fact, IGHV-M patients are generally characterized by indolent clinical course, even if a significant fraction of these patients progressed and required treatment. To date, no prognostic factor has proven to predict effectively clinical aggressiveness in these patients, and this observation was confirmed in our data set where no standard biological and clinical features were able to predict clinical outcome in terms of TTFT among early stage IGHV-M CLL patients (data not shown). In this context, IGF1R might represent a potentially useful prognostic marker of TTFT among patients with theoretically indolent biological (IGHV-M) and favorable clinical profile at diagnosis (Binet stage A). This suggestion is reinforced by the evidence that IGF1R retained its significant correlation in multivariate analysis. Among cMBL, IGF1R expression could be an important indicator of disease aggressiveness albeit this needs to be validated in larger cohort with longer follow up.

IGF1R gene and protein levels and activity were recently reported to be strongly associated with the NOTCH1 pathway in patients affected by T-ALL, in which it is frequently involved and activated by mutations or molecular aberrations [7]. Activating NOTCH1 mutations have recently been reported by many groups as one of the most frequent aberrations in refractory and transformed CLL [32–35]; NOTCH1 c.7541_7542delCT allelic variant represents the most frequent aberration, accounting for more than 80% of all mutations [18,32–35]. According to NOTCH1 mutation data in our cohort, we observed that patients harboring NOTCH1 c.7541_7542delCT mutation were characterized by a significant IGF1R up-regulation. Thus, it may suggest the existence of potentially altered signalling pathway, such as IGF1R, in CLL patients harboring NOTCH1 mutation. Based on these data, IGF1R activity may provide an important growth and survival advantage to CLL cells, similar to what has recently been reported in T-ALL [7].

Trisomy 12 was historically described as intermediate cytogenetic aberration characterized by heterogeneous clinical course [3]. This was confirmed also in our prospective series where a fraction of trisomy 12 patients showed an indolent clinical course, whereas the others had a more aggressive evolution and short TTFT. This latter group was generally characterized by IGHV-UM and/or high CD38, NOTCH1 mutation, high IGF1R. In fact, patients with trisomy 12 showing low IGF1R expression, and IGHV-M and NOTCH1 wt status were generally characterized by indolent clinical course. These data strengthen the potential role of IGF1R to discriminate aggressive entities among “apparently intermediate” and/or “favorable CLL”.

Recent improvements in gene sequencing have demonstrated the importance of subclones in cancer development. As reported in our previous study, NOTCH1 mutation was defined as subclonal in all patients with positive ARMS-PCR and negative by Sanger sequencing [18]. All these patients were characterized by a mutation allele burden between 0.7 and 7%. Comparing subclonal vs. clonal mutated NOTCH1 patients, no significant clinical or biological difference was observed [18], and this was true also for IGF1R expression (data not shown). The potential prognostic and biological role of subclonal gene mutations in CLL is a matter of debate [18,36,37]; available data suggest that clonal and subclonal mutations share common clinical and biological features, thus suggesting a potential perturbation of the same signalling pathways.

Overall, our study shows the importance of IGF1R expression in CLL and its strong association with specific adverse clinical and biological features, confirming the interest for the study of this gene as a potential prognostic factor and its possible role as a therapeutic target in a specific group of CLL patients carrying trisomy 12 and NOTCH1 mutations.

Supporting Information

The correlation coefficients of expression levels were assessed for all transcripts and are shown in the chart. Both the microarray and Q-RT-PCR data have been scaled in the range 0–1.

(TIF)

(TIF)

(DOCX)

Data Availability

Gene expression data has been deposited in the National Centre for Biotechnology Information’s Gene Expression Omnibus database http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/ and are accessible through series accession number GSE51529.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by Associazione Italiana Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC, AN-IG10136, MF464 IG10492, and FM-RG6432), AIRC–Special Program Molecular Clinical Oncology (5 per Mille, grant 9980, 2010-15; Antonino Neri, Manlio Ferrarini, and Fortunato Morabito), Ricerca Finalizzata from the Italian Ministry of Health 2006 (Giovanna Cutrona, Fortunato Morabito, and Manlio Ferrarini) and 2007 (Giovanna Cutrona), Fondo Investimento per la Ricerca di Base (grant RBIP06LCA9; Manlio Ferrarini), progetto Compagnia San Paolo (G.C.). Sabrina Bossio was supported by fellowships from the AIRC. Marta Lionetti was supported by a fellowship from the Fondazione Italiana Ricerca sul Cancro (FIRC). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Crespo M, Bosch F, Villamor N, Bellosillo B, Colomer D, Rozman M, et al. ZAP-70 expression as a surrogate for immunoglobulin-variable-region mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2003;348: 1764–1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hallek M, Cheson BD, Catovsky D, Caligaris-Cappio F, Dighiero G, Dohner H, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a report from the International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia updating the National Cancer Institute-Working Group 1996 guidelines. Blood 2008;111: 5446–5456. 10.1182/blood-2007-06-093906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dohner H, Stilgenbauer S, Benner A, Leupolt E, Krober A, Bullinger L, et al. Genomic aberrations and survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2000;343: 1910–1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Damle RN, Wasil T, Fais F, Ghiotto F, Valetto A, Allen SL, et al. Ig V gene mutation status and CD38 expression as novel prognostic indicators in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 1999;94: 1840–1847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hamblin TJ, Davis Z, Gardiner A, Oscier DG, Stevenson FK. Unmutated Ig V(H) genes are associated with a more aggressive form of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 1999;94: 1848–1854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pollak M. The insulin and insulin-like growth factor receptor family in neoplasia: an update. Nat Rev Cancer 2012;12: 159–169. 10.1038/nrc3215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Medyouf H, Gusscott S, Wang H, Tseng JC, Wai C, Nemirovsky O, et al. High-level IGF1R expression is required for leukemia-initiating cell activity in T-ALL and is supported by Notch signaling. J Exp Med. 2011;208: 1809–1822. 10.1084/jem.20110121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kuhn DJ, Berkova Z, Jones RJ, Woessner R, Bjorklund CC, Ma W, et al. Targeting the insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor to overcome bortezomib resistance in preclinical models of multiple myeloma. Blood 2012;120: 3260–3270. 10.1182/blood-2011-10-386789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Moreau P, Cavallo F, LeLeu X, Hulin C, Amiot M, Descamps G, et al. Phase I study of the anti insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF-1R) monoclonal antibody, AVE1642, as single agent and in combination with bortezomib in patients with relapsed multiple myeloma. Leukemia 2011;25: 872–874. 10.1038/leu.2011.4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schillaci R, Galeano A, Becu-Villalobos D, Spinelli O, Sapia S, Bezares RF. Autocrine/paracrine involvement of insulin-like growth factor-I and its receptor in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2005;130: 58–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yaktapour N, Ubelhart R, Schuler J, Aumann K, Dierks C, Burger M, et al. Insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF1R) as a novel target in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 2013;122: 1621–1633. 10.1182/blood-2013-02-484386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Morabito F, Mosca L, Cutrona G, Agnelli L, Tuana G, Ferracin M, et al. Clinical monoclonal B lymphocytosis versus Rai 0 chronic lymphocytic leukemia: A comparison of cellular, cytogenetic, molecular, and clinical features. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19: 5890–5900. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cutrona G, Colombo M, Matis S, Reverberi D, Dono M, Tarantino V, et al. B lymphocytes in humans express ZAP-70 when activated in vivo. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36: 558–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cutrona G, Colombo M, Matis S, Fabbi M, Spriano M, Callea V, et al. Clonal heterogeneity in chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells: superior response to surface IgM cross-linking in CD38, ZAP-70-positive cells. Haematologica 2008;93: 413–422. 10.3324/haematol.11646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Morabito F, Cutrona G, Gentile M, Matis S, Todoerti K, Colombo M, et al. Definition of progression risk based on combinations of cellular and molecular markers in patients with Binet stage A chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2009;146: 44–53. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07703.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fabris S, Mosca L, Todoerti K, Cutrona G, Lionetti M, Intini D, et al. Molecular and transcriptional characterization of 17p loss in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2008;47: 781–793. 10.1002/gcc.20579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Maura F, Cutrona G, Fabris S, Colombo M, Tuana G, Agnelli L, et al. Relevance of stereotyped B-cell receptors in the context of the molecular, cytogenetic and clinical features of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. PLoS One 2011;6: e24313 10.1371/journal.pone.0024313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lionetti M, Fabris S, Cutrona G, Agnelli L, Ciardullo C, Matis S, et al. High-throughput sequencing for the identification of NOTCH1 mutations in early stage chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: biological and clinical implications. Br J Haematol. 2014;165: 629–639. 10.1111/bjh.12800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cheson BD, Bennett JM, Grever M, Kay N, Keating MJ, O'Brien S, et al. National Cancer Institute-sponsored Working Group guidelines for chronic lymphocytic leukemia: revised guidelines for diagnosis and treatment. Blood 1996;87: 4990–4997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stamatopoulos K, Belessi C, Moreno C, Kay N, Keating MJ, O'Brien S, et al. Over 20% of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia carry stereotyped receptors: Pathogenetic implications and clinical correlations. Blood 2007;109: 259–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Vishwamitra D, Shi P, Wilson D, Manshouri R, Vega F, Schlette EJ, et al. Expression and effects of inhibition of type I insulin-like growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase in mantle cell lymphoma. Haematologica 2011;96: 871–880. 10.3324/haematol.2010.031567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liang Z, Diepstra A, Xu C, van IG, Plattel W, Van Den BA, et al. Insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor is a prognostic factor in classical hodgkin lymphoma. PLoS One 2014;9: e87474 10.1371/journal.pone.0087474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hartog H, Horlings HM, van der Vegt B, Kreike B, Ajouaou A, van de Vijver MJ, et al. Divergent effects of insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor expression on prognosis of estrogen receptor positive versus triple negative invasive ductal breast carcinoma. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;129: 725–736. 10.1007/s10549-010-1256-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Papa V, Gliozzo B, Clark GM, McGuire WL, Moore D, Fujita-Yamaguchi Y, et al. Insulin-like growth factor-I receptors are overexpressed and predict a low risk in human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 1993;53: 3736–3740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fu P, Ibusuki M, Yamamoto Y, Hayashi M, Murakami K, Zheng S, et al. Insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor gene expression is associated with survival in breast cancer: a comprehensive analysis of gene copy number, mRNA and protein expression. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;130: 307–317. 10.1007/s10549-011-1605-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dziadziuszko R, Merrick DT, Witta SE, Mendoza AD, Szostakiewicz B, Szymanowska A, et al. Insulin-like growth factor receptor 1 (IGF1R) gene copy number is associated with survival in operable non-small-cell lung cancer: a comparison between IGF1R fluorescent in situ hybridization, protein expression, and mRNA expression. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28: 2174–2180. 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.6611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ahlén J, Wejde J, Brosjö O, von Rosen A, Weng WH, Girnita L, et al. Insulin-like growth factor type 1 receptor expression correlates to good prognosis in highly malignant soft tissue sarcoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11: 206–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yousfi MM, Giudicelli V, Chaume D, Lefranc MP. IMGT/JunctionAnalysis: the first tool for the analysis of the immunoglobulin and T cell receptor complex V-J and V-D-J JUNCTIONs. Bioinformatics 2004;20 Suppl 1: i379–i385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Byrd JC, Furman RR, Coutre SE, Flinn IW, Burger JA, Blum KA, et al. Targeting BTK with ibrutinib in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2013;369: 32–42. 10.1056/NEJMoa1215637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gopal AK, Kahl BS, de Vos S, Wagner-Johnston ND, Schuster SJ, Jurczak WJ, et al. PI3Kdelta Inhibition by Idelalisib in Patients with Relapsed Indolent Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Furman RR, Sharman JP, Coutre SE, Cheson BD, Pagel JM, Hillmen P, et al. Idelalisib and Rituximab in Relapsed Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fabbri G, Rasi S, Rossi D, Trifonov V, Khiabanian H, Ma J, et al. Analysis of the chronic lymphocytic leukemia coding genome: role of NOTCH1 mutational activation. J Exp Med. 2011;208: 1389–1401. 10.1084/jem.20110921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Puente XS, Pinyol M, Quesada V, Trifonov V, Khiabanian H, Ma J, et al. Whole-genome sequencing identifies recurrent mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Nature 2011;475: 101–105. 10.1038/nature10113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rossi D, Rasi S, Fabbri G, Spina V, Fangazio M, Forconi F, et al. Mutations of NOTCH1 are an independent predictor of survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 2012;119: 521–529. 10.1182/blood-2011-09-379966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wang L, Lawrence MS, Wan Y, Stojanov P, Sougnez C, Stevenson K, et al. SF3B1 and other novel cancer genes in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2011;365: 2497–2506. 10.1056/NEJMoa1109016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Landau DA, Carter SL, Stojanov P, McKenna A, Stevenson K, Lawrence MS, et al. Evolution and impact of subclonal mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cell 2013;152: 714–726. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rossi D, Khiabanian H, Spina V, Ciardullo C, Bruscaggin A, Fama R, et al. Clinical impact of small TP53 mutated subclones in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 2014;123: 2139–2147. 10.1182/blood-2013-11-539726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The correlation coefficients of expression levels were assessed for all transcripts and are shown in the chart. Both the microarray and Q-RT-PCR data have been scaled in the range 0–1.

(TIF)

(TIF)

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

Gene expression data has been deposited in the National Centre for Biotechnology Information’s Gene Expression Omnibus database http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/ and are accessible through series accession number GSE51529.