Graphical Abstract

Keywords: Yellow-bellied marmot, Cryptosporidium, Sierra Nevada, Mountains, Elevation, C. parvum

Highlights

-

•

Yellow-bellied marmots of Sierra Nevada Mountain shed Cryptosporidium oocysts.

-

•

Oocysts loads are low compared to other mammals in California.

-

•

Shedding of oocysts is associated with altitude and vegetation type.

-

•

Cryptosporidium oocysts were 99.9%–100% match to Cryptosporidium parvum.

Abstract

Wildlife are increasingly recognized as important biological reservoirs of zoonotic species of Cryptosporidium that might contaminate water and cause human exposure to this protozoal parasite. The habitat range of the yellow-bellied marmot (Marmota flaviventris) overlaps extensively with the watershed boundaries of municipal water supplies for California communities along the foothills of the Sierra Nevada. We conducted a cross-sectional epidemiological study to estimate the fecal shedding of Cryptosporidium oocysts by yellow-bellied marmots and to quantify the environmental loading rate and determine risk factors for Cryptosporidium fecal shedding in this montane wildlife species. The observed proportion of Cryptosporidium positive fecal samples was 14.7% (33/224, positive number relative to total number samples) and the environmental loading rate was estimated to be 10,693 oocysts animal-1 day-1. Fecal shedding was associated with the elevation and vegetation status of their habitat. Based on a portion of the 18s rRNA gene sequence of 2 isolates, the Cryptosporidium found in Marmota flaviventris were 99.88%–100% match to multiple isolates of C. parvum in the GenBank.

1. Introduction

The protozoa of the genus Cryptosporidium are obligate, intracellular parasites affecting a large number of vertebrate species including humans. Cryptosporidium oocysts are resistant to chlorine disinfection and can cause waterborne enteric disease. Even though humans and livestock are considered major biological reservoirs of Cryptosporidium oocysts (Mac Kenzie et al., 1994; Xiao and Ryan, 2004; Atwill et al., 2006a; Feltus et al., 2006; Nichols et al., 2006; Brook et al., 2009; Santin, 2013), wildlife are increasingly recognized as significant sources of water contamination with this parasite (Jiang et al., 2005; Feng et al., 2007; Ruecker et al., 2007, 2012; Chalmers et al., 2010). Wild rodents have been identified as hosts for several Cryptosporidium species, including species causing disease in humans (Morgan et al., 1999; Hajdusek et al., 2004; Feng et al., 2007; Kimura et al., 2007; Meireles et al., 2007; Raskova et al., 2013). Specifically in the Marmota genus, reported Cryptosporidium species include C. andersoni and C. ubiquitum (Ryan et al., 2003; Feng et al., 2007), suspected C. parvum (Atwill et al., 2003), as well as undetermined species (Ziegler et al., 2007).

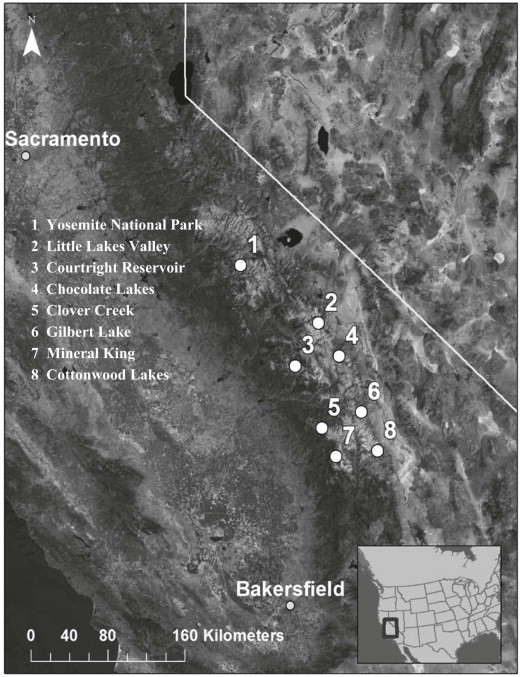

The Sierra Nevada is a mountain range extending along the border between California and Nevada with the Sacramento and San Joaquin Valleys to the west and the Basin and Range region to the east (Fig. 1). The Sierra Nevada Range annual snowpack and the surface water generated from snowmelt constitute major sources of municipal and recreational water for California. Above 6,000 feet (~1830 meters), this mountain range encompasses the habitats of several species of mammals including the yellow-bellied marmot (Marmota flaviventris) (Sumner and Dixon, 1953). Given the extensive spatial overlap between the range of this rodent and the watershed boundaries for municipal water supplies for California communities along the foothills of the Sierra Nevada, we conducted a cross-sectional epidemiological study to estimate the prevalence of Cryptosporidium in yellow-bellied marmots and quantify the Environmental Loading Rate [ELR] (Atwill et al., 2003, 2004) of oocysts from these rodents. Through the construction of a hierarchical Bayesian logistic regression, we tested if habitat characteristics are associated with Cryptosporidium oocyst shedding in these rodents.

Fig. 1.

Locations in the Sierra Nevada Mountains where scat samples from yellow-bellied marmot were collected. The map contains 14 locations, but some locations clustered together due to the shorter distances between them and the scale of the map. The cluster in Yosemite National Park includes Tenaya Creek, Bridaveil Creek, Pothole Dome, and Lembert Dome. The cluster at Mineral King includes Mineral King, Eagle Lake, White Chief Creek, and Elk Kaweah River.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Sample collection

Naturally voided fecal samples were collected opportunistically at 14 different locations between June and July 2012 from sites where yellow-bellied marmots defecate. These locations were in the Sequoia National Park, Inyo National Forest, Sierra National Forest, and Yosemite National Park, extending approximately 200 kilometers from north to south, at the eastern and western sides of the Sierra Nevada, California (Table 1, Fig. 1). These locations were selected as suitable habitat for yellow-bellied marmots or were locations where marmots were previously reported. We visited each location once, collecting fresh scat samples found within 4–5 hours. The recognition of feces as from yellow-bellied marmot was based on sighting individuals at every location and by using descriptions and characterizations of marmot scat (Murie and Elbroch, 2005). Only adult sized scat samples were collected in order to avoid collecting feces from other smaller rodent species. To obtain only fresh fecal samples, samples were selected from scat that were moist and with flies present. In order to minimize the chance of sampling feces from the same animal, only one scat was selected from each site within a location, and no additional samples were collected within 20 m diameter surrounding the scat sampled. Approximately 1.6 g of fecal sample was collected from each sampling site.

Table 1.

The locations where marmot scat samples were collected in Sierra Nevada Mountains.

| Area | Sampling location | Elevation range | Latitude | Longitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sierra National Forest | Courtright Reservoir | 8131-8365 | 37° 10' 8.94'' N | 118° 33' 57.06'' W |

| Sequoia National Park | Mineral King | 7567-8089 | 36° 27' 2.25'' N | 118° 35' 41.1216'' W |

| Eagle Lake | 9319-10144 | 36° 24' 52.6824''N | 118° 36' 22.7664'' W | |

| White Chief Creek | 8980-9561 | 36° 25' 25.1364'' N | 118° 34' 30.2412'' W | |

| Elk Kaweah River | 8316-9380 | 36° 24' 53.1072'' N | 118° 35' 11.0976'' W | |

| Clover Creek | 8801-9286 | 36° 39' 23.5296'' N | 118° 43' 24.7224'' W | |

| Inyo Forest |

Cottonwood Lakes | 11003-11073 | 36° 29' 30.7428'' N | 118° 12' 24.6168'' W |

| Gilbert Lake | 10478-10538 | 36° 46' 11.4492'' N | 118° 21' 20.6928'' W | |

| Chocolate Lakes | 10112a | 37° 6' 1.728'' N | 118° 58' 21.9036'' W | |

| Little Lakes Valley | 10492-10728 | 37° 24' 20.2356'' N | 118° 45' 31.5612'' W | |

| Yosemite National Park | Tenaya Creek | 8421-8696 | 37° 48' 45.6228'' N | 119° 29' 6.7632'' W |

| Bridaveil Creek | 6985-7164 | 37° 39' 41.76'' N | 119° 37' 7.464'' W | |

| Pothole Dome | 8704-9688 | 37° 52' 56.5428'' N | 119° 22' 31.9224'' W | |

| Lembert Dome | 8610-8941 | 37° 52' 49.0008'' N | 119° 21' 2.7756'' W |

Only one sample.

Fecal samples were placed into 50 ml polypropylene sterile centrifuge tubes containing 5 ml of antibiotic storage solution (0.1 ml 10% Tween 20, 0.006 g penicillin G, 0.01 g streptomycin sulfate, 1.0 ml amphotericin B solution in 100 ml reagent-grade water). Tubes were kept on ice at 4 °C until transported to the laboratory at University of California at Davis. For each sampling site, coordinates and elevation (ft) above sea level were obtained using a GPS device GPSMAP® 76Cx (Garmin, Olathe, KS, USA) with an accuracy of ≤ 5 m. Location and date of collection were recorded.

2.2. Environmental parameters

Occurrence of vegetation at the sampling sites was recorded as two categories: no vegetation due to predominately rocky substrate; and vegetation, predominately meadow of grasses and sedges or woody species such as trees. The vegetation category assigned to each sample site was based on direct visual observation and supported by the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index developed by the National Agriculture Imagery Program (California Department of Fish and Wildlife, 2010). Lastly, the mode of human access to each sampling site was recorded as trail, if hiking was necessary to reach the site, or dirt/paved road if the site was accessible by vehicle. We used this variable as an index of human presence in the marmot habitats in order to evaluate its association with Cryptosporidium oocysts in the feces. In sampling locations accessible by a dirt/paved road, people are more likely to pass through the location in vehicles, while the presence of a hiking trail suggests more chances of people walking across the location and potentially defecating.

2.3. Detecting Cryptosporidium oocysts

The detection of Cryptosporidium oocysts from fecal samples was based on published methods (Kuczynska and Shelton, 1999; Pereira et al., 1999) with modifications. Briefly, feces were weighed, resuspended in PBS, and strained into 50 ml centrifuge tubes through 4 layers of cotton gauze. Tubes were centrifuged at 1500 g for 15 min, supernatant was discarded, and pellet was resuspended in 5 ml of deionized water. The fecal solution was mixed with 30 ml of sucrose solution (specific gravity ~1.2) and centrifuged at 1000 g for 25 min. Oocysts were collected from the top of sucrose solution by overlaying 5 ml of deionized water, gently stirring, and pipetting 5 ml from the top. Oocysts were washed by mixing with deionized water and centrifuging at 1500 g for 15 min. The supernatant was discarded by aspiration, leaving a 1:1 ratio of pellet to solution volume. This final solution was weighed and 10 µl was overlaid on commercially prepared slides (Waterborne Inc., New Orleans, LA) and weighed too. Smears were air dried, stained using a direct immunofluorescence antibody kit (Meridian Bioscience, Inc., Cincinnati, OH), and examined using an Olympus BX60 microscope at ×400 magnification. Slides containing one or more oocysts were recorded as positive while those without detectable oocysts were recorded as negative. The crude number of oocysts per gram feces (O), unadjusted by assay percent recovery, was calculated according to the formula: O = [N × (Wsusp/Wsm)] / F, where N is the number of oocysts in the smear, Wsusp and Wsm are the suspension and smear weight respectively, and F is the fecal weight. Assuming daily consistent oocyst shedding, the Environmental Loading Rate [ELR] was calculated using the mean number of oocysts per gram of feces found in this study and a crude estimate for total daily fecal production estimated as ~3% of mean body mass or 0.02 kg feces wet weight per day for a typical adult marmot (Atwill et al., 2003).

2.4. Statistical analysis

In order to evaluate the effect of environmental parameters on the likelihood of detecting Cryptosporidium oocysts in marmot feces, a hierarchical Bayesian logistic regression model was constructed using JAGS 3.4.0 (http://mcmc-jags.sourceforge.net, [9–15-10], [Plummer, M.]) in R 2.15.1 (http://www.r-project.org, [10-10-11], [Development Core Team] ), with R2jags 0.03–08 (http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/R2jags/index.html, [11–17-2012], [Yu-Su and Masanao]) as the interface. The outcome yij was the presence of Cryptosporidium oocysts (0 = no oocysts / 1 = oocysts present) in the ni feces collected at the j locations:, where the probability of Cryptosporidium oocysts being present in the ith yellow-bellied marmot feces sampled at location j, pij was related to a suite of q fixed predictors at the feces level: elevation and vegetation.

where αj[i] are random intercepts shared by feces belonging to location j, defined as:

where is the group level predictor mode of human access used to reach each sampling location. We selected a hierarchical model because yellow-bellied marmot fecal samples were grouped by sampling location. This grouping was based on the assumption that the probability of Cryptosporidium infection in marmots from the same location may not be independent from each other and therefore may exhibit a level of positive correlation in and above what is accounted for in a fixed effects regression model. Moreover, a Bayesian approach is preferred over the frequentist because the former can avoid problems of identification when the multilevel model is complicated.

Given the continuous nature of the variable elevation, we evaluated graphically the assumption of linearity with respect to the log odds of a fecal sample testing positive for Cryptosporidium oocysts by categorizing elevation into 4 strata based on quartiles to get an equal number of observations per stratum elevation: 6,985–8,265 (reference level), 8,265–9,068, 9,068–10,057, and >10,057 ft. Across these four strata, there was a non-linear association between elevation and the log odds of Cryptosporidium oocysts shedding, therefore a quadratic term for elevation was considered. Moreover, to determine if effect modification was present between vegetation and elevation, the full dataset was stratified by vegetation status and the relationship reevaluated between elevation and the log odds of Cryptosporidium shedding within each strata.

For model construction, the variable elevation was centered at its mean: 9,068 ft, and the quadratic elevation term was constructed from these centered values. Non-informative priors or hyperpriors were assigned for βq, β0 and and: Normal (0, 25) for the first three parameters and LogNormal (0,1) for the last one. Posterior distributions for all parameters were sampled from each of three chains for 60,000 iterations following a 10,000 iteration burn-in, and thinning set to 5, for a total of 30,000 samples. Each chain was assigned random start values from a Normal (0,1) distribution for β0 and βq and a Uniform (0,1) for σ. Convergence was assessed by the Gelman–Rubin statistic (Gelman and Rubin, 1992). A backward stepping procedure was used to select terms for the final model, starting with a full model containing the random intercepts, the fixed effects, and two-way interactions: among elevation and vegetation, and quadratic elevation and vegetation. Final model selection was based on the deviance information criterion (DIC) (Spiegelhalter et al., 2002) and credibility of parameters. Given the sample size and the sparse nature of data, fixed regression parameters with 90% Credible Intervals [CrI] that excluded 0 were considered to be credible. We assessed potential confounders by examining the change of the mean parameter estimate when they were included to the selected model. If the inclusion generated a change >10%, we kept the variable in the model.

2.5. PCR and sequencing

Fecal solutions of microscopic positive samples were exposed to 5 cycles of freeze (−80 °C) and thaw (+70 °C), then 0.2 g fecal solutions were used for DNA extraction using the DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen®) according to the manufacturer's manual. A nested PCR was performed using primers and reaction conditions amplifying a fragment of ~830 bp of the 18S rRNA gene according to previously described methods (Xiao et al., 1999). A positive control using C. parvum DNA from California dairy calves (GenBank accession no. FJ752165) as template and a negative control without DNA template were included in each PCR. PCR products were verified by electrophoresis in 2% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide. Verified PCR products were purified using a Qiaquick® spin columns (Qiagen®) and sequenced at the University of California DNA Sequencing Facility, where ABI 3730 Capillary Electrophoresis Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems Inc., Foster City, CA) was used for sequencing. Primers of the secondary PCR of the 18s rRNA gene were used for sequencing. A preliminary analysis of sequences was conducted using Vector NTI Advanced 11 software (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA) followed by a BLAST analysis to compare the sequences to existing Cryptosporidium spp. 18S rRNA gene sequences in the GenBank using the National Center for Biotechnology Information [NCBI] online blasting tool (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/).

3. Results

3.1. Fecal shedding of Cryptosporidium oocysts

A total of 224 fecal samples were collected. Thirty three (~15%) fecal samples had detectable levels of Cryptosporidium oocysts (95% CI: 10.0–19.4%). Among these 33 positive fecal samples, 22 had one oocyst, 6 had 2 oocysts, 2 had 4 oocysts and one of each had 8, 26 and 35 oocysts per smear. This distribution of oocyst shedding intensity resulted in a mean of 535 oocysts per gram of feces wet weight (95% CI: 204–865), ranging from 35 to 1,646 and a median value of 129 oocysts per gram of feces. The mean ELR was estimated as 10,693 Cryptosporidium oocysts per adult marmot per day.

Elevations of the sample collection sites ranged from 6,985 to 11,070 ft, with a median elevation of 9,068 ft. Total sample size of sites with and without vegetation was 158 and 66 respectively, with a median elevation of 8,657 and 9,374 ft, respectively. Bridaveil Creek, Chocolate Lakes, Courtright Reservoir, Lembert Dome, Pothole Dome, and Tenaya Creek were accessed from dirt/paved roads and the remaining locations were reached through hiking trails. The prevalences of Cryptosporidium oocysts in fecal samples collected at sites with and without vegetation were 11% and 23%, respectively. A summary of the number of samples collected by location and the positive proportion is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Prevalence of Cryptosporidium oocysts in yellow-bellied marmot feces in locations with different vegetation status (sampling locations are sorted by ascending elevation).

| Location | Total | Overall prev. [%] (95% CI) | Vegetation | No vegetation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Pos. | Prev. [%] (95% CI) | Total | Pos. | Prev. [%] (95% CI) | |||

| Bridaveil Creek | 11 | 18 (2–52) | 6 | 2 | 33 (4–78) | 5 | 0 | 0 (0–52) |

| Elk Kaweah River | 11 | 18 (2–52) | 10 | 2 | 20 (3–56) | 1 | 0 | 0 (0–98) |

| Courtright Reservoir | 39 | 10 (3–24) | 29 | 3 | 10 (2–27) | 10 | 1 | 10 (0–45) |

| Tenaya Creek | 20 | 30 (12–54) | 1 | 0 | 0 (0–98) | 19 | 6 | 32 (13–57) |

| Lembert Dome | 12 | 25 (5–57) | 3 | 1 | 33 (1–91) | 9 | 2 | 22 (3–60) |

| Pothole Dome | 7 | 43 (10–82) | 0 | 0 | - | 7 | 3 | 43 (10–82) |

| Mineral King | 16 | 19 (4–46) | 16 | 3 | 19 (4–46) | 0 | 0 | - |

| Clover Creek | 7 | 43 (10–82) | 0 | 0 | - | 7 | 3 | 43 (10–82) |

| White Chief Creek | 25 | 12 (3–31) | 24 | 3 | 12 (3–32) | 1 | 0 | 0 (0–98) |

| Eagle Lake | 23 | 0 (0–15) | 18 | 0 | 0 (0–19) | 5 | 0 | 0 (0–52) |

| Chocolate Lakes | 1 | 0 (0–98) | 1 | 0 | 0 (0–98) | 0 | 0 | - |

| Gilbert Lake | 3 | 0 (0–71) | 1 | 0 | 0 (0–98) | 2 | 0 | 0 (0–84) |

| Little Lakes Valley | 6 | 0 (0–46) | 6 | 0 | 0 (0–46) | 0 | 0 | - |

| Cottonwood Lakes | 43 | 9 (3–22) | 43 | 4 | 9 (3–22) | 0 | 0 | - |

| TOTAL | 224 | 15 (10–20) | 158 | 18 | 11 (7–17) | 66 | 15 | 23 (13–35) |

3.2. Environmental parameters on fecal shedding of oocysts

Parameter estimates and odds ratios [OR] from the final regression model are presented in Table 3. In the final regression model, the estimates for both two-way interactions were evaluated: the centered elevation and vegetation status, and the square of centered elevation with vegetation status, resulting in credible OR. As a consequence of these credible OR, the variables elevation, quadratic elevation and vegetation status were retained in the selected final model. Simpler models without these interaction terms resulted in larger DICs and the non-credibility of the remaining parameters. The mode of human access to the marmot site was kept in the final model as a confounder because it adjusted elevation's mean parameter estimate by approximately 14%.

Table 3.

Estimated Bayesian hierarchical logistic regression coefficients for environmental factors associated with Cryptosporidium oocysts in feces of yellow-bellied marmots in the Sierra Nevada Mountains, California.

| Parameter | Level | Coefficient (90% CrI) | Odds ratio (90% CrI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −2.110 (−2.942, −1.291) | 0.121 (0.053, 0.275) | |

| Vegetation | Absence | 1.111 (−0.363, 2.454) | 3.038 (0.695, 11.638) |

| Presence | 0 | 1 | |

| Elevation | −0.524 (−1.050, −0.018) | 0.592 (0.350, 0.982) | |

| Elevation2 | 0.098 (−0.276, 0.443) | 1.103 (0.759, 1.557) | |

| Elevation × Vegetation | Absence | −3.013 (−6.555, −0.046) | 0.049 (0.001, 0.955) |

| Presence | 0 | 1 | |

| Elevation2 × Vegetation | Absence | −5.208 (−9.357, −1.828) | 0.005 (0.0001, 0.161) |

| Presence | 0 | 1 | |

| Access | Road | −0.346 (−1.549, 0.867) | 1.413 (0.213,2.380) |

| Trail | 0 | 1 | |

| σ2among-locations | 0.473 (−0.659, 0.750) |

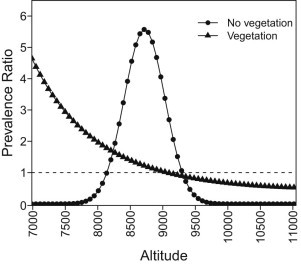

The association between elevation and the odds for Cryptosporidium oocysts in marmot feces was strongly influenced by the presence or absence of vegetation at the sampling sites. When vegetation was present, the odds of detecting oocysts decreased as site elevation increased (Table 3). For example, at sites where access was via a hiking trail, the odds of detecting oocysts in marmot feces was about 5 times more likely at sites at 7,000 ft elevation compared to feces collected at sites of 9,000 ft elevation. In contrast, for fecal samples collected at rocky location with minimal vegetation, it was rare to find fecal samples with Cryptosporidium oocysts from sites at the extreme lower or higher elevations. Instead, positive samples clustered in the middle to upper 8,000 ft range (Fig. 2). The variance among random intercepts was estimated at 0.473; however, the CrI for this estimate covered zero, suggesting that significantly different random intercepts for locations were not present.

Fig. 2.

Association between Cryptosporidium oocyst shedding by yellow-bellied marmots in the Sierra Nevada Mountains and elevation (using 9,068 ft as the reference), stratified by presence or absence of vegetation at sites where scat samples were collected.

3.3. PCR and sequencing

Amplification and sequencing of a fragment of the 18S rRNA gene were successful for two of the microscopic positive samples. The two samples were collected from Bridaveil Creek in Yosemite National Park (isolate 1) and Mineral King in Sequoia National Park (isolate 2). Sequence analysis of the two Cryptosporidium isolates demonstrates that they were 99.76% (828/830 bases) similar to each other. Given that the Cryptosporidium oocysts were isolated from Marmota flaviventris in 2012, the two isolates we named as Mflav12a(1) and Mflav12a(2), respectively. The GenBank accession numbers of the two isolates are KF626380 for Mflav 12a (1) (isolate 1) and KF626381 for Mflav 12a (2) (isolate 2), respectively. Using the NCBI's default algorithm parameters to target maximum 100 sequences in GenBank, the Mflav12a(1) isolate was 100% similar to a C. parvum isolate (KM225275) and 99.88% similar to C. parvum isolates of the most closely related 10 entries in GenBank (Table 4). Similarly, the Mflav12a(2) isolate was 100% identical to two C. parvum isolates (JN247404 and KC476546) and 99.88% similar to C. parvum isolates of the other 8 entries in GenBank (Table 4) (based on BLAST analysis completed on December 29, 2014).

Table 4.

Comparison of Cryptosporidium isolates from yellow-bellied marmots (Marmota flaviventris) to Cryptosporidium isolates in GenBank.

| Location | DNA sequence group (isolate) | GenBank access no. | No. of base pairs | GenBank access no. of closely related isolates | Country of origin | Max. identity a (%) by BLAST |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bridaveil Creek (Yosemite National Park) | Mflav12a(1) (isolate 1) |

KF626380 | 830 | KM225275 (C. parvum Jammu) | USA | 100 |

| AB513857-513863 (C. parvum Sakha 102–108) | Egypt | 99.88 | ||||

| AB441687 (C. parvum strain Cap (C) 197IR) | Iran | 99.88 | ||||

| EF611871 (C. parvum isolate Izatnagar) | India | 99.88 | ||||

| DQ523504 (C. parvum clone 3229T) | Spain | 99.88 | ||||

| DQ656355 (C. parvum isolate IR-C2) | Iran | 99.88 | ||||

| L16996 (C. parvum isolate AUCP-1) | USA | 99.88 | ||||

| AY204238 (C. parvum clone HMa) | USA | 99.88 | ||||

| AF161856 (C. parvum strain MT) | USA | 99.88 | ||||

| AF108864 (C. parvum strain C1) | Australia | 99.88 | ||||

| AF040725 (C. parvum strain KSU-1) | USA | 99.88 | ||||

| Mineral King (Sequoia National Park) | Mflav12a(2) (isolate 2) |

KF626381 | 830 | JN247404 (C. parvum BRAsheep53CII) | Brazil | 100 |

| KC476546 (C. parvum strain 98C) | Poland | 100 | ||||

| JX948126 (C. parvum isolate A23G) | Thailand | 99.88 | ||||

| KM225275 (C. parvum Jammu) | USA | 99.88 | ||||

| AB513857-513863 (C. parvum Sakha 102–108) | Egypt | 99.88 | ||||

| AB441687 (C. parvum strain Cap (C) 197IR) | Iran | 99.88 | ||||

| EF611871 (C. parvum isolate Izatnagar) | India | 99.88 | ||||

| DQ523504 (C. parvum clone 3229T) | Spain | 99.88 | ||||

| DQ656355 (C. parvum isolate IR-C2) | Iran | 99.88 | ||||

| L16996 (C. parvum isolate AUCP-1) | USA | 99.88 | ||||

| AY204238 (C. parvum clone HMa) | USA | 99.88 |

Examples of isolates of Cryptosporidium that represent entries in the GenBank with the highest percentage match of their 18S rRNA gene sequence with the two new isolates from yellow-bellied marmots.

4. Discussion

To standardize the sampling procedure, we searched for scat samples at each location during a similar period of time; however, the number of samples by location varied due to the difference in abundance of marmots at each location. We sampled naturally voided fecal deposits and collected only one scat sample per site so as to minimize repeated sampling of the same animal. The home range of yellow-bellied marmots can vary in size and shape (Armitage, 2009) and they can live in colonies or as satellites (Armitage and Downhower, 1974), thus it is not possible to guarantee that each fecal sample belongs to different individuals. Nevertheless, point prevalence estimated in this study (~15%) is similar to the prevalence reported from studies on related mammalian species (Feng et al., 2007; Ziegler et al., 2007; Feng, 2010). The ELR as reported previously for this host species was 208,000 oocysts animal−1 day−1 (Atwill et al., 2003), which represents a 20-fold higher value compared with the value calculated for this study. However, values reported in the present work are the crude number of oocysts per gram of feces which is unadjusted by percent recovery. In our laboratory, the percent recovery can typically range from 9 to over 30% depending on the vertebrate species being tested (Atwill et al., 2003, 2006a), which results in a 3.3- to 11.1-fold increase in the estimated ERL as reported previously for this host species (Atwill et al., 2003). The estimated ELR from this study is less than the values reported previously for horses (Equus caballus), striped skunks (Mephitis mephitis), coyotes (Canis latrans), and California ground squirrels (Spermophilus beecheyi), but higher than the daily loads reported for adult dairy cattle (Bos taurus) and beef cattle (Bos taurus) (Atwill et al., 2003, 2004).

The role of elevation as a risk factor for Cryptosporidium oocysts fecal shedding could be explained by the effects of variables that vary with elevation, such as temperature, desiccation and ultraviolet (UV) radiation. In general, as elevation increases: a) temperature decreases as a result of the air expansion under lower pressure; b) relative humidity decreases as a consequence of lower air temperature and pressure; and c) UV radiation increases due to decreasing density of molecules and particles in the atmosphere. Temperature is a key factor for the survival of intact oocysts on the ground (Fayer, 1994; Jenkins et al., 1999; Olson et al., 1999; Nasser et al., 2007) and in feces (Jenkins et al., 1999; Olson et al., 1999; Kato et al., 2002; Li et al., 2005, 2010). Exposure to ambient temperatures in excess of 30 °C to 40 °C has been shown to inactivate or reduce oocyst infectivity (Anderson, 1985; Fayer, 1994; Li et al., 2005, 2010). Moreover, oocysts have been shown to be susceptible to freeze/thaw cycles (Jenkins et al., 1999) and freezing (Kato et al., 2002). At high elevations, freeze/thaw cycles might occur, but it seems oocysts are more likely affected by heat than cold (Olson et al., 1999; Nasser et al., 2007). Desiccation has been shown to strongly reduce oocyst viability (Anderson, 1986; Robertson et al., 1992; Deng and Cliver, 1999; Nasser et al., 2007). UV radiation inactivates or reduces infectivity of C. parvum oocysts (Lorenzo-Lorenzo et al., 1993; Campbell et al., 1995; Craik et al., 2001; Drescher et al., 2001; Linden et al., 2001; Shin et al., 2001; Morita et al., 2002; Rochelle et al., 2004; Connelly et al., 2007; King et al., 2008, 2010; Lee et al., 2008). In this cross-sectional study, we did not include variables of temperature, desiccation, or UV radiation, but these should be considered in future studies of fecal shedding of oocysts by yellow-bellied marmots. In addition, it would be necessary to consider other factors potentially influencing these variables, for example, slope direction.

Buffer strips of vegetation have been shown to retain Cryptosporidium oocysts (Davies et al., 2004; Tate et al., 2004; Trask et al., 2004; Atwill et al., 2006b; McLaughlin et al., 2013); therefore, sites with vegetation could potentially have higher oocyst loads to which marmots could become exposed and infected. Vegetation could also influence oocyst inactivation rates by protecting them from higher temperatures, desiccation and UV radiation. We speculate that the negative association between the odds for oocyst shedding and elevation for marmots located in vegetated habitat (Fig. 2) may be the consequence of vegetation reducing oocyst exposure to UV radiation at lower elevation. The effect of vegetation protection is probably related with changes of plant species as elevation increases which lead to higher inactivation rates of oocysts in the environment. With respect to sites with no vegetation, oocysts in fecal material can be removed by the runoff from precipitation, thus reducing oocysts loads (Davies et al., 2004; Tate et al., 2004; Trask et al., 2004); McLaughlin et al., 2013; Davidson et al., 2014). Therefore in these areas, infection of susceptible individuals would likely occur in zones with higher density of marmots and closer contact between animals. According to our results, clusters of positive fecal samples existed at locations harboring a higher density of individuals.

This work describes what we believe to be the first detection of Cryptosporidium from yellow-bellied marmots in the unique high elevation locations in Sierra Nevada Mountains. PCR amplification of DNA of Cryptosporidium oocysts from fecal samples is frequently hampered due to the many inhibitors present in fecal samples, as experienced by our laboratory and reported by others (Kostrzynska et al., 1999; Xiao et al., 2003; Adamska et al., 2012; Elmore et al., 2013). Although only two isolates were successfully sequenced, our results demonstrate that some of these oocysts recovered are likely to be C. parvum. Because C. parvum is a species that infects humans and a wide range of vertebrate animals (Fayer, 2010), there is the potential of transmission between mammal species in the Sierra Nevada Mountains, such as marmots, horses, wildlife, and humans. In addition, Cryptosporidium shed by yellow-bellied marmots could potentially contaminate water sources used for drinking or recreation in the mountains. However, a valid risk assessment of waterborne outbreaks needs to take into consideration the density of the local yellow-bellied marmot population, the low loads of oocysts shed by these animals, the environmental factors that influence the survival and viability of the oocysts, and hydrological transport of oocysts in the environment.

In summary, yellow-bellied marmots in the Sierra Nevada Mountains are hosts of Cryptosporidium spp. with estimated prevalence of 10–20%. Some of the marmots in these populations are likely the hosts of C. parvum. The estimated ELR for these animals is lower than values reported for other mammals in California. Fecal shedding of Cryptosporidium oocysts by yellow-bellied marmots is associated with elevation and strongly influenced by the presence or absence of vegetation.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that there is no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Danielle Pederson for her assistance in laboratory procedures of detecting Cryptosporidium oocysts from fecal samples in this study.

References

- Adamska M., Leonska-Duniec A., Sawczuk M., Maciejewska A., Skotarczak B. Recovery of Cryptosporidium from spiked water and stool samples measured by PCR and real time PCR. Vet. Med. (Praha) 2012;57:224–232. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson B.C. Moist heat inactivation of Cryptosporidium sp. Am. J. Public Health. 1985;75:1433–1434. doi: 10.2105/ajph.75.12.1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson B.C. Effect of drying on the infectivity of cryptosporidia-laden calf feces for 3-to 7-day-old mice. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1986;47:2272–2273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armitage K.B. Home range area and shape of yellow-bellied marmots. Ethol. Ecol. Evol. 2009;21:195–207. [Google Scholar]

- Armitage K.B., Downhower J.F. Demography of yellow-bellied marmot populations. Ecology. 1974;55:1233–1245. [Google Scholar]

- Atwill E.R., Phillips R., Rulofson F. Estimating environmental loading rates of the waterborne pathogenic protozoa, Cryptosporidium parvum, in certain domestic and wildlife species in California. 2003. http://escholarship.ucop.edu/uc/item/0c5054fm Sierra Foothill Research & Extension Center, Agriculture and Natural Resources Research and Extension Centers, UC Davis. accessed 13.07.03.

- Atwill E.R., Phillips R., Pereira M.D., Li X., McCowan B. Seasonal shedding of multiple Cryptosporidium genotypes in California ground squirrels (Spermophilus beecheyi) Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004;70:6748–6752. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.11.6748-6752.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atwill E.R., Pereira M.D., Alonso L.H., Elmi C., Epperson W.B., Smith R. Environmental load of Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts from cattle manure in feedlots from the central and western United States. J. Environ. Qual. 2006;35:200–206. doi: 10.2134/jeq2005.0099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atwill E.R., Tate K.W., das Gracas Cabral Pereira M., Bartolome J., Nader G. Efficacy of natural grassland buffers for removal of Cryptosporidium parvum in rangeland runoff. J. Food Prot. 2006;69:177–184. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-69.1.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook E.J., Anthony Hart C., French N.P., Christley R.M. Molecular epidemiology of Cryptosporidium subtypes in cattle in England. Vet. J. 2009;179:378–382. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2007.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- California Department of Fish and Wildlife Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) applied to the source National Agriculture Imagery Program 2010 imagery. 2010. https://map.dfg.ca.gov/arcgis/rest/services/Base_Remote_Sensing/NAIP_2010_NDVI/ImageServer accessed 05.05.2013.

- Campbell A.T., Robertson L.J., Snowball M.R., Smith H.V. Inactivation of oocysts of Cryptosporidium parvum by ultraviolet irradiation. Water Res. 1995;29:2583–2586. [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers R.M., Robinson G., Elwin K., Hadfield S.J., Thomas E., Watkins J. Detection of Cryptosporidium species and sources of contamination with Cryptosporidium hominis during a waterborne outbreak in North West Wales. J. Water Health. 2010;8:311–325. doi: 10.2166/wh.2009.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connelly S.J., Wolyniak E.A., Williamson C.E., Jellison K.L. Artificial UV-B and solar radiation reduce in vitro infectivity of the human pathogen Cryptosporidium parvum. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007;41:7101–7106. doi: 10.1021/es071324r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craik S.A., Weldon D., Finch G.R., Bolton J.R., Belosevic M. Inactivation of Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts using medium-and low-pressure ultraviolet radiation. Water Res. 2001;35:1387–1398. doi: 10.1016/s0043-1354(00)00399-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson P.C., Kuhlenschmidt T.B., Bhattarai R., Kalita P.K., Kuhlenschmidt M.S. Effects of soil type and cover condition on Cryptosporidium parvum transport in overland flow. Water Air Soil Poll. 2014;225:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Davies C.M., Ferguson C.M., Kaucner C., Krogh M., Altavilla N., Deere D.A. Dispersion and transport of Cryptosporidium Oocysts from fecal pats under simulated rainfall events. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004;70:1151–1159. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.2.1151-1159.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng M.Q., Cliver D.O. Cryptosporidium parvum studies with dairy products. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 1999;46:113–121. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(98)00187-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drescher A.C., Greene D.M., Gadgil A.J. Cryptosporidium inactivation by low-pressure UV in a water disinfection device. J. Environ. Health. 2001;64:31–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmore S.A., Lalonde L.F., Samelius G., Alisauskas R.T., Gajadhar A.A., Jenkins E.J. Endoparasites in the feces of arctic foxes in a terrestrial ecosystem in Canada. Int. J. Parasitol. Wildl. 2013;2:90–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ijppaw.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fayer R. Effect of high temperature on infectivity of Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts in water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1994;60:2732–2735. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.8.2732-2735.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fayer R. Taxonomy and species delimitation in Cryptosporidium. Exp. Parasitol. 2010;124:90–97. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltus D.C., Giddings C.W., Schneck B.L., Monson T., Warshauer D., McEvoy J.M. Evidence supporting zoonotic transmission of Cryptosporidium spp. in Wisconsin. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2006;44:4303–4308. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01067-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y. Cryptosporidium in wild placental mammals. Exp. Parasitol. 2010;124:128–137. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y., Alderisio K.A., Yang W., Blancero L.A., Kuhne W.G., Nadareski C.A. Cryptosporidium genotypes in wildlife from a New York watershed. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007;73:6475–6483. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01034-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman A., Rubin D.B. Inference from iterative simulation using multiple sequences. Stat. Sci. 1992;7:457–472. [Google Scholar]

- Hajdusek O., Ditrich O., Slapeta J. Molecular identification of Cryptosporidium spp. in animal and human hosts from the Czech Republic. Vet. Parasitol. 2004;122:183–192. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins M., Walker M., Bowman D., Anthony L., Ghiorse W. Use of a sentinel system for field measurements of Cryptosporidium parvum oocyst inactivation in soil and animal waste. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999;65:1998–2005. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.5.1998-2005.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J., Alderisio K.A., Xiao L. Distribution of Cryptosporidium genotypes in storm event water samples from three watersheds in New York. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005;71:4446–4454. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.8.4446-4454.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato S., Jenkins M.B., Fogarty E.A., Bowman D.D. Effects of freeze-thaw events on the viability of Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts in soil. J. Parasitol. 2002;88:718–722. doi: 10.1645/0022-3395(2002)088[0718:EOFTEO]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura A., Edagawa A., Okada K., Takimoto A., Yonesho S., Karanis P. Detection and genotyping of Cryptosporidium from brown rats (Rattus norvegicus) captured in an urban area of Japan. Parasitol. Res. 2007;100:1417–1420. doi: 10.1007/s00436-007-0488-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King B.J., Hoefel D., Daminato D., Fanok S., Monis P. Solar UV reduces Cryptosporidium parvum oocyst infectivity in environmental waters. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2008;104:1311–1323. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2007.03658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King B.J., Hoefel D., Wong P.E., Monis P.T. Solar radiation induces non-nuclear perturbations and a false start to regulated exocytosis in Cryptosporidium parvum. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e11773. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostrzynska M., Sankey M., Haack E., Power C., Aldom J.E., Chagla A.H. Three sample preparation protocols for polymerase chain reaction based detection of Cryptosporidium parvum in environmental samples. J. Microbiol. Methods. 1999;35:65–71. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7012(98)00106-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczynska E., Shelton D.R. Method for detection and enumeration of Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts in feces, manures, and soils. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999;65:2820–2826. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.7.2820-2826.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.U., Joung M., Yang D.J., Park S.H., Huh S., Park W.Y. Pulsed-UV light inactivation of Cryptosporidium parvum. Parasitol. Res. 2008;102:1293–1299. doi: 10.1007/s00436-008-0908-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Atwill E.R., Dunbar L.A., Jones T., Hook J., Tate K.W. Seasonal temperature fluctuations induces rapid inactivation of Cryptosporidium parvum. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005;39:4484–4489. doi: 10.1021/es040481c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Atwill E.R., Dunbar L.A., Tate K.W. Effect of daily temperature fluctuation during the cool season on the infectivity of Cryptosporidium parvum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010;76:989–993. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02103-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden K.G., Shin G., Sobsey M.D. Comparative effectiveness of UV wavelengths for the inactivation of Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts in water. Water Sci. Technol. 2001;43:171–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo-Lorenzo M.J., Ares-Mazas M.E., De Maturana I.V.M., Duran-Oreiro D. Effect of ultraviolet disinfection of drinking water on the viability of Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts. J. Parasitol. 1993;79:67–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mac Kenzie W.R., Hoxie N.J., Proctor M.E., Gradus M.S., Blair K.A., Peterson D.E. A massive outbreak in Milwaukee of Cryptosporidium infection transmitted through the public water supply. N. Engl. J. Med. 1994;331:161–167. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199407213310304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin S.J., Kalita P.K., Kuhlenschmidt M.S. Fate of Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts within soil, water, and plant environment. J. Environ. Manage. 2013;131:121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2013.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meireles M.V., Soares R.M., Bonello F., Gennari S.M. Natural infection with zoonotic subtype of Cryptosporidium parvum in Capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris) from Brazil. Vet. Parasitol. 2007;147:166–170. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2007.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan U.M., Sturdee A.P., Singleton G., Gomez M.S., Gracenea M., Torres J. The Cryptosporidium “mouse” genotype is conserved across geographic areas. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1999;37:1302–1305. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.5.1302-1305.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita S., Namikoshi A., Hirata T., Oguma K., Katayama H., Ohgaki S. Efficacy of UV irradiation in inactivating Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002;68:5387–5393. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.11.5387-5393.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murie O.J., Elbroch M. 2005. A field guide to animal tracks. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. [Google Scholar]

- Nasser A., Tweto E., Nitzan Y. Die-off of Cryptosporidium parvum in soil and wastewater effluents. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2007;102:169–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.03048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols R.A., Campbell B.M., Smith H.V. Molecular fingerprinting of Cryptosporidium oocysts isolated during water monitoring. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006;72:5428–5435. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02906-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson M.E., Goh J., Phillips M., Guselle N., McAllister T.A. Giardia cyst and Cryptosporidium oocyst survival in water, soil, and cattle feces. J. Environ. Qual. 1999;28:1991–1996. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira M.D., Atwill E.R., Jones T. Comparison of sensitivity of immunofluorescent microscopy to that of a combination of immunofluorescent microscopy and immunomagnetic separation for detection of Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts in adult bovine feces. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999;65:3236–3239. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.7.3236-3239.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raskova V., Kvetonova D., Sak B., McEvoy J., Edwinson A., Stenger B. Human cryptosporidiosis caused by Cryptosporidium tyzzeri and C. parvum isolates presumably transmitted from wild mice. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2013;51:360–362. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02346-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson L., Campbell A., Smith H. Survival of Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts under various environmental pressures. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1992;58:3494–3500. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.11.3494-3500.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochelle P.A., Fallar D., Marshall M.M., Montelone B.A., Upton S.J., Woods K. Irreversible UV inactivation of Cryptosporidium spp. despite the presence of UV repair genes. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 2004;51:553–562. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2004.tb00291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruecker N.J., Braithwaite S.L., Topp E., Edge T., Lapen D.R., Wilkes G. Tracking host sources of Cryptosporidium spp. in raw water for improved health risk assessment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007;73:3945–3957. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02788-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruecker N.J., Matsune J.C., Wilkes G., Lapen D.R., Topp E., Edge T.A. Molecular and phylogenetic approaches for assessing sources of Cryptosporidium contamination in water. Water Res. 2012;46:5135–5150. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2012.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan U., Xiao L., Read C., Zhou L., Lal A.A., Pavlasek I. Identification of novel Cryptosporidium genotypes from the Czech Republic. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003;69:4302–4307. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.7.4302-4307.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santin M. Clinical and subclinical infections with Cryptosporidium in animals. N. Z. Vet. J. 2013;61:1–10. doi: 10.1080/00480169.2012.731681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin G.A., Linden K.G., Arrowood M.J., Sobsey M.D. Low-pressure UV inactivation and DNA repair potential of Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001;67:3029–3032. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.7.3029-3032.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegelhalter D.J., Best N.G., Carlin B.P., Van Der Linde A. Bayesian measures of model complexity and fit. J. R. Stat. Soc. B. 2002;64:583–639. [Google Scholar]

- Sumner L., Dixon J.S. Univ. of California Press; Berkeley: 1953. Birds and Mammals of the Sierra Nevada: With Records from Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks. [Google Scholar]

- Tate K.W., Pereira M.D., Atwill E.R. Efficacy of vegetated buffer strips for retaining Cryptosporidium parvum. J. Environ. Qual. 2004;33:2243–2251. doi: 10.2134/jeq2004.2243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trask J.R., Kalita P.K., Kuhlenschmidt M.S., Smith R.D., Funk T.L. Overland and near-surface transport of Cryptosporidium parvum from vegetated and nonvegetated surfaces. J. Environ. Qual. 2004;33:984–993. doi: 10.2134/jeq2004.0984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao L., Ryan U.M. Cryptosporidiosis: an update in molecular epidemiology. Curr. Opin. Infec. Dis. 2004;17:483–490. doi: 10.1097/00001432-200410000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao L., Escalante L., Yang C., Sulaiman I., Escalante A.A., Montali R.J. Phylogenetic analysis of Cryptosporidium parasites based on the small-subunit rRNA gene locus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999;65:1578–1583. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.4.1578-1583.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao L., Bern C., Sulaima I.M., Lal A.A. Molecular epidemiology of human cryptosporidiosis. In: Thompson R.C.A., Armson A., Ryan U.M., editors. Cryptosporidium from molecules to disease. ELSEVIER B. V.; Amsterdam, the Netherlands: 2003. pp. 121–140. [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler P.E., Wade S.E., Schaaf S.L., Stern D.A., Nadareski C.A., Mohammed H.O. Prevalence of Cryptosporidium species in wildlife populations within a watershed landscape in southeastern New York State. Vet. Parasitol. 2007;147:176–184. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2007.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]