Abstract

Background:

The purpose of this study was to assess the clinical and microbiological effects of the local and sub-gingival application of a hyaluronan gel on scaling and root planing (SRP) in the treatment of moderate generalized chronic periodontitis.

Materials and Methods:

In this split mouth study, 72 teeth in 18 patients with generalized chronic periodontitis with moderate severity were chosen for the study. Plaque samples were obtained by paper points at required intervals. Contra-lateral pairs of premolars and canine teeth in the maxilla or the mandible were selected to receive test treatment or serve as controls. Experimental jaw quadrants received sub-gingival administration of 0.2-ml 0.8% hyaluronan gel into selected sites following SRP and 1-week later. Clinical parameters were assessed at baseline, 1st, 4th, and 12th week. Colony-forming units (CFU) per milliliter were assessed at baseline, after SRP and after 2 weeks of drug insertion Student t-test and repeated measure ANOVA (RMANOVA) were used in this study. RMANOVA was used to find the significance in bleeding on probing (BOP) and plaque index (PI) and t-test for probing pocket depth (PPD) and clinical attachment level (CAL).

Results:

The results revealed that there was a significant reduction in BOP (P < 0.001) PI (P < 0.001), PPD (P < 0.001) and CAL (P < 0.001) were also observed in experimental jaw quadrant following SRP and insertion of 0.8% hyaluronan when compared with the control group. A statistically significant reduction of CFUs was also found (P < 0.001) in the experimental site when compared with the control site.

Conclusion:

Sub-gingival placement of 0.2-ml of 0.8% hyaluronan along with SRP resulted in a significant improvement in both clinical and microbiological parameters when compared with the control site.

Keywords: Hyaluronan gel, scaling and root planing, sub-gingival application

INTRODUCTION

Periodontal ligament consists of large amounts of matrix macromolecules such as collagen, glycosaminoglycans, and noncollagenous proteins. Hyaluronan is one major component of extracelluar matrix of periodontium.[1] Chemical usage is widely been practiced to treat oral diseases. Various antibiotics (minocycline, tetracycline, metronidazole, and hexidine) and anti-inflammatory agents, such as flurbiprofen and triclosan, have been trialed in previous studies. However, recent initiatives have started to use chemotherapeutic agents. The side-effects of systemic antibiotic therapy and the possible poor compliance of the patient can be minimized by using antibiotics locally.[2] Hyaluronic acid (HA) is also known as hyaluronan or hyaluronate is a nonsulfated polysaccharide component of glycosaminoglycan family with high molecular weight. In 1950s, Meyer et al. established that hyaluronan is a linear polymer built from repeating disaccharide units with the structure D-glucuronic acid (1-β-3) N-Acetyl –D- glucosamine (1-β4)n.[3]

Hyaluronic acid is a component of the connective tissue and is also found in gingiva. It has been studied as a metabolite or marker of inflammation in the gingival crevicular fluid as well as a significant factor in the growth, development, and repair of tissues. Being high in molecular weight, HA stimulates early healing and reparative dentine formation.[4] Only a few studies have examined the effect of hyaluronan on gingival health. Less is known about the effect of sub-gingival administration of hyaluronan on periodontitis. The aim of the present study is to assess the clinical and microbiological effects of sub-gingival application of 0.8% hyaluronan gel [Figure 1] as an adjunct to scaling and root planing (SRP) in the treatment of generalized chronic periodontitis with moderate severity.

Figure 1.

0.8% hyaluronan gel (gengigel) pack containing prefilled syringes and flexible tips

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Eighteen patients (11 males and 7 females) who visited the Department of Periodontics, SIBAR Institute of Dental Sciences, Guntur were recruited for this study. A total of 72 teeth in 18 patients were included in the study. Written and verbal consent was taken from the patients and ethical approved was attained by the institutional committee prior to study commencement. Patients were aged 30-60 years and not under any antibiotic therapy and dental prophylaxis for last 6 months. Other inclusion criteria included ≥20 teeth present with at least 5 inter proximal sites with probing depth (PD)≥5-mm [Figure 2]. Those not meeting the above inclusion criteria for example, aged below 30 or above 60 years, those whom received periodontal treatment within last 6 months or patients with a history of severe systemic disease, such as a cardiovascular, renal, hepatic, or immunologic disorders were excluded.

Figure 2.

Probing depth of 6-mm at base line

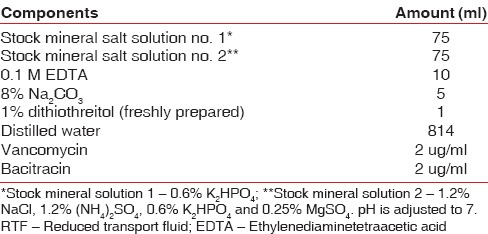

The periodontal plaque samples are collected using sterile paper points (ISO 40 size) at baseline, after SRP and after 2 weeks of drug insertion. These are then transferred into reduced transport fluid (RTF). Each individual contributed microbial samples from periodontal pockets that were ≥5-mm. Sample sites were isolated with cotton rolls and one sterile paper point (Paper Points ISO 40) was inserted to the depth of each periodontal pocket sampled and retained there for 20 s. The paper points were then transferred to a 2-ml screw-cap polyvinyl containing RTF transport medium [Table 1]. Reduced transport fluid to be the most suitable medium for transport and recovery of bacteria from supra-gingival dental plaque. Subzero storage (−196°C and −40°C) did not enhance the survival of bacteria from dental plaque; storage at moderate (5°C and 20°C) temperatures gave better recovery of viable bacteria. Survival after anaerobic or aerobic storage was comparable for total colony-forming units (CFU).[5]

Table 1.

Composition of RTF

Samples were collected and incubated at room temperature for 3-4 h to allow the bacteria adjust to the media, and then vials were refrigerated to control growth. Transportation to laboratory was undertaken with samples at <15°C using icepacks.

Microbial load

Microbial load per sample is estimated by determining the CFU/ml of the sample. Several test runs were performed and 10−4 dilution was selected as most suitable dilution for the CFU determination. Serial dilutions were performed using sterile RTF medium and were plated onto appropriate media plates. These were allowed to incubate under anaerobic conditions of 37°C for 7 days in an anaerobic chamber (80:10:10, N2:H2:CO2). Data were recorded as the count of CFUs/ml on the growth plate. Each sample triplicates of plates were maintained for accuracy and the mean of all three plates were reported.[6]

Processing of samples

For isolation of obligate anaerobes, the samples were plated on nonselective Anaerobic Thioglycolate Medium Base (ATMB) agar plates supplemented with horse serum (5%), kanamycin-vancomycin-bacitracin, used for selective recovery of obligate anaerobic Gram-negative rods.

Culture conditions

In brief, the following plates were inoculated and incubated at 37°C for 7 days in an anaerobic chamber (80/10/10, N2/H2/CO2). Aliquots of 0.1-ml of the appropriate dilution were also spread onto ATMB (+ serum, bacitracin 75 ug/ml, vancomycin 5 ug/ml) or trypticase soy, serum, bacitracin 75 ug/ml, vancomycin 5 ug/ml [TSBV]) agar plates, a selective medium for periodontal microbes and then cultured at 37°C in a microaerophilic environment (5% CO2, 95% N2). After 7 days, the TSBV agar plates were examined for the presence of colonies, adherent to the culture plates.

All patients underwent SRP at baseline. Contra-lateral pairs of premolars and canine teeth in the maxilla or the mandible were randomized to receive the test treatment or to serve as controls. Experimental jaw quadrants received the identical protocol with the addition of sub-gingival administration of 0.2-ml 0.8% hyaluronan gel into selected sites following SRP whereas the control site received only SRP without any placebo gel [Figure 3]. Randomization was done through a coin toss method. Hyaluronan gel was readministered into the selected sites after 1-week at the test site. The periodontal status of patients included in the study was recorded using the following periodontal parameters: Plaque index (PI)[7] by Silness and Loe, bleeding on probing (BOP), probing pocket depth (PPD), clinical attachment level (CAL). PI and BOP were evaluated pretreatment at baseline and at 1, 4, and 12 weeks posttreatment. PD and CAL were evaluated at baseline and after 12 weeks [Figure 4].

Figure 3.

Insertion of 0.8% hyaluronan gel after scaling and root planing

Figure 4.

Reduction in probing pocket depth to 1-mm after 3 months

Statistical analysis

Descriptive and inferential statistical analyses have been carried out in this study. Results on continuous measurements are presented on mean ± standard deviation (SD) (Min-Max) and results on categorical measurements are presented in number (%). Significance is assessed at 5% level of significance. The statistical software namely SAS 9.2, SPSS 15.0, Stata 10.1, MedCalc 9.0.1, Systat 12.0 and R environment version 2.11.1 were used for the analysis of the data and Microsoft word and Excel have been used to generate graphs and tables. Student t-test (two tailed, dependent) and repeated measure ANOVA (RMANOVA) has been used to find the significance of study parameters.

RESULTS

The age of the patients ranged between 30 and 60 years with a mean ± SD: 45.00 ± 10.12. The average mean age of males was 47.09 and females were 41.71. The percentage of distribution was 61% and 38.9%, respectively.

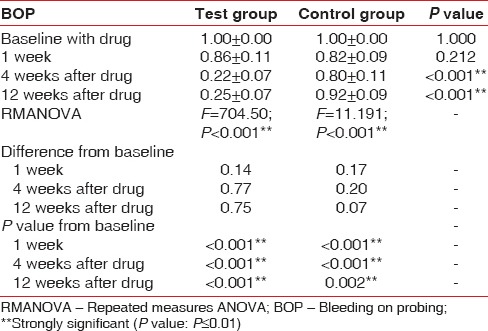

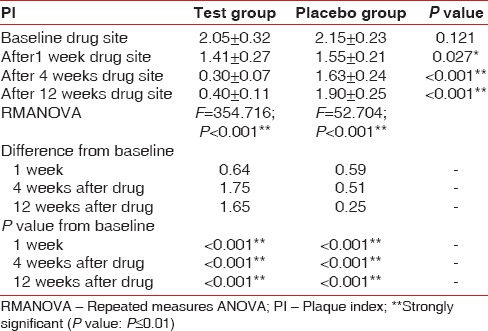

At baseline, the test site and control site had a mean BOP of 1.00 ± 0.00, which reduced to 0.22 ± 0.07 in the test and 0.80 ± 0.11 in the control with a P < 0.001 after 12 weeks. The RMANOVA shows an F = 704.5 in the test site and 11.19 in the control site with a statistical significance of P < 0.001 after 12 weeks [Table 2 and Graph 1].

Table 2.

Comparison of BOP in test group and control group at baseline, 1st, 4th, and 12th week

Graph 1.

Changes in mean bleeding index

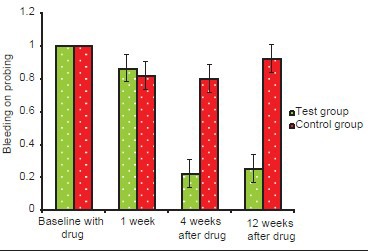

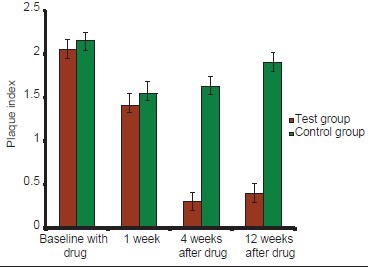

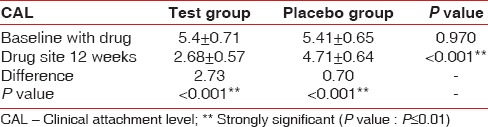

At baseline, the test and control sites have a mean PI of 2.05 ± 0.32 and 2.15 ± 0.23, P = 0.121) which reduced to 0.40 ± 0.11in the test and 1.90 ± 0.25 in control, P < 0.001. The RMANOVA shows an F value of 354.71 in the test site and 52.70 in the control site with a P < 0.001 after 12 weeks [Table 3 and Graph 2]. PI scores are reduced significantly at the end of 3 months in the test group when compared with the control group.

Table 3.

Comparison of PI in test group and control group at baseline, 1st, 4th, and 12th week

Graph 2.

Changes in mean plaque index

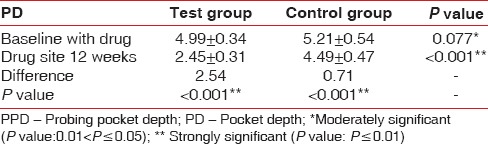

A statistically significant difference was also observed between baseline and at the end of 3 months with respect to PPD scores P < 0.001. The PPD was 4.99 ± 0.34 in test sites at baseline and 5.21 ± 0.54 in control sites at baseline. After 3 months the PPD reduced to 2.45 ± 0.31 in the test and 4.49 ± 0.47 in the control sites [Table 4 and Graph 3].

Table 4.

Comparison of PPD in test group and control group at baseline and 12th week

Graph 3.

Changes in mean probing pocket depth

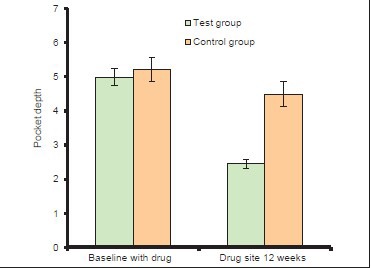

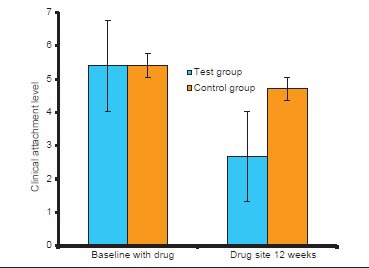

A statistically significant reduction was also observed at the end of 3rd month when compared with baseline bleeding with respect to CAL scores P < 0.001. At baseline, CAL score was 5.4 ± 0.71 in the test sites and 5.41 ± 0.65 in control sites, which reduced to 2.68 ± 0.57 in test sites whereas in control sites it is 4.71 ± 0.64 [Table 5 and Graph 4].

Table 5.

Comparison of CAL in test group and control group at baseline and 12th week

Graph 4.

Changes in mean clinical attachment level

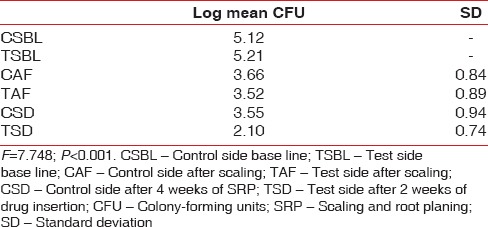

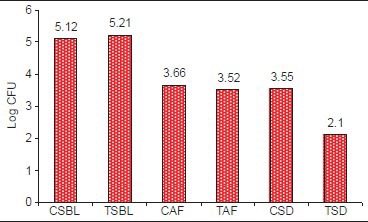

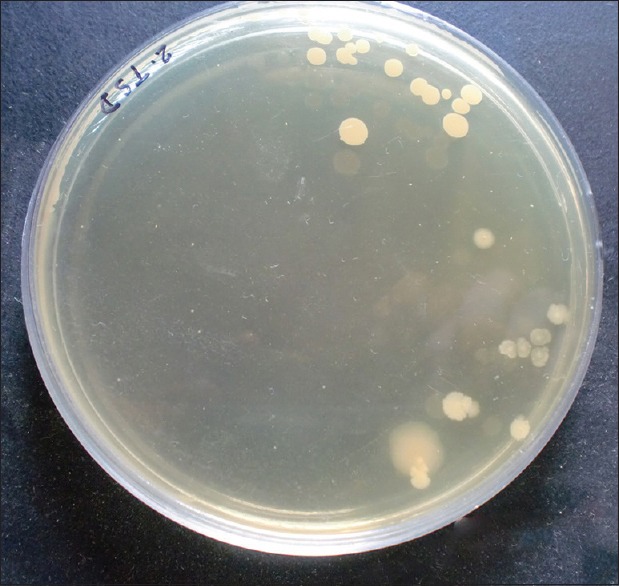

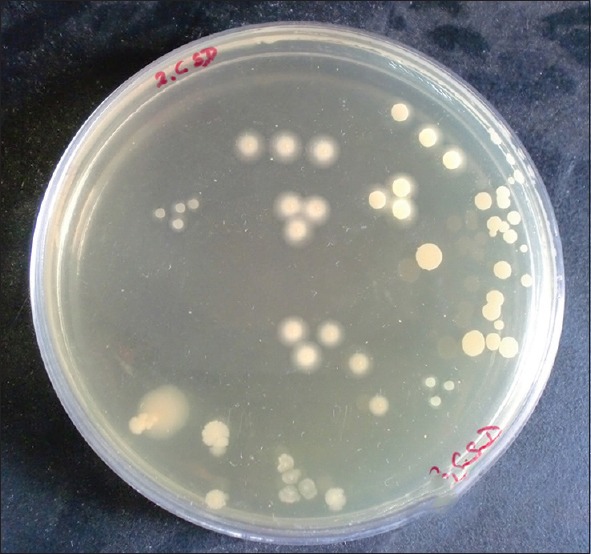

Statistically significant reduction was also observed in the CFU from baseline at test site when compared with control site with a P < 0.001 [Table 6 and Graph 5]. At baseline, the CFU/ml was 5.21 × 106 CFU/ml in test site and 5.12 × 106 CFU/ml in control site which reduced to 2.10 × 105 [Figure 5] in test site whereas in control site 3.55 × 105 CFU/ml [Figure 6].

Table 6.

Comparison of CFU level in test group and control group at baseline and after SRP 12th and 2 weeks after drug insertion

Graph 5.

Changes in the colony-forming units

Figure 5.

Colony-forming units in test site after 2 weeks of drug insertion

Figure 6.

Colony-forming units in control site after 4 weeks of scaling and root planing

DISCUSSION

Hyaluronic acid is used in the restoration of periodontal integrity due to its complex interactions with the extracellular matrix and its components.[8] This study analyzed the effects of additional sub-gingival application of HA gel after SRP in 18 patients with generalized moderate chronic periodontitis. Clinical variables and CFUs were examined after 2 weeks and 3 months after drug insertion. Unlike other studies where CFUs were not assessed, in this study CFUs were assessed at baseline, after SRP and 2 weeks after drug insertion. A statistically significant reduction in the CFUs was observed in the test site when compared with the control site after 2 weeks of drug insertion because HA has bacteriostatic effect on certain periodontopathic pathogens and HA also decreased the growth rate of these organisms. Hyaluronan was shown to have antibacterial action upto certain extent, in particular on Aggregatibacter actinomycetencomitans, Prevotella intermedia, Staphylococcus aureus and Propionibacterium strains.[9]

Certain bacterial species, e.g. Treponema denticola, have a hyaluronidase action. Consequently, saturation of the bacterial hyaluronidases, which are needed to break through the physiologic HA network, may have prevented bacterial spread. Furthermore, effective pretreatment of periodontitis patients before SRP may have some influence.[10] Hyaluronan seemed to be able to stabilize these low counts for a longer period and prevent the early regrowth of these bacterial species. A significant reduction in the microbiological load was also reported in the sites treated with HA gel and SRP when compared with SRP alone in this study which are in accordance with other studies conducted by Pirnazar et al.[9] [INLINE:4] [INLINE:5]

In this split mouth study, SRP with HA gel treated test sites showed improvement in all clinical parameters such as BOP, PI, PPD, and CAL when compared with the control sites. These results are consistent with the studies of Eick et al.[10] and Pilloni et al.[11] where a positive change in all the clinical parameters like PD and CAL were reported. The improvement in PPD and CAL was more noticeable in test group in comparison with control group suggesting a positive effect of HA gel on wound healing.

The study conducted by Johannsen et al.[12] who also applied 0.8% HA gel sub-gingivally demonstrated reduction in BOP, PD and PI in test site when compared with the SRP alone. An improvement in CAL and recession was also reported in 14 patients with intra bony defects who were treated with HA gel along with periodontal surgery.[13]

A statistically significant reduction in BOP was presented in the study. This observation is in concert with the previous results of improved gingival health after supra-gingival application of hyaluronan in gingivitis.[4,14,15] The reduction in the gingival inflammation is attributed to the antiinflammatory and antiedematous effect of Hyaluronan.

Pistorius et al.[14] showed that HA gel produced a significant improvement in plaque induced gingivitis compared with placebo. A 5-time daily application of HA spray over a week or twice-daily topical application of hyaluronan gel adjunctive to conventional oral hygiene over 3 weeks significantly reduced gingivitis. Though there is appreciable clinical and microbiological results with the use of HA gel few limitations have been observed in the study. The study was done for a short duration with a small sample size and confined to bilateral canine and premolar teeth exhibiting similar disease pattern. Since it is not possible to identify the exact periodontal pathogens by using CFUs use of polymerase chain reaction would have been an additional benefit to this study to determine the effects of HA on specific organism. Further longitudinal studies with large sample size are required to assess the action of hyaluronan in periodontitis patients.

CONCLUSION

Within the limitations of the current study sub-gingival placement of 0.8% HA gel along with SRP provided a significant improvement in periodontal parameters in the test site after a 3-month period when compared with control site. HA showed positive effects in influencing inflammation and wound healing.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ohno S, Ijuin C, Doi T, Yoneno K, Tanne K. Expression and activity of hyaluronidase in human periodontal ligament fibroblasts. J Periodontol. 2002;73:1331–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.2002.73.11.1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sapna N, Vandana KL. Evaluation of hyaluronan gel (gengigel) as a topical applicant in the treatment of gingivitis. J Investig Clin Dent. 2011;2:162–70. doi: 10.1111/j.2041-1626.2011.00064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meyer K, Palmer JW. The polysaccharide of the vitreous humor. J Biol Chem. 1934;107:629–34. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jentsch H, Pomowski R, Kundt G, Göcke R. Treatment of gingivitis with hyaluronan. J Clin Periodontol. 2003;30:159–64. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2003.300203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoover C, Newbrun E. Survival of bacteria from human dental plaque under various transport conditions. J Clin Microbiol. 1977;6:212–8. doi: 10.1128/jcm.6.3.212-218.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slots J. Selective medium for isolation of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. J Clin Microbiol. 1982;15:606–9. doi: 10.1128/jcm.15.4.606-609.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silness J, Loe H. Periodontal disease in pregnancy. II. Correlation between oral hygiene and periodontal condtion. Acta Odontol Scand. 1964;22:121–35. doi: 10.3109/00016356408993968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moseley R, Waddington RJ, Embery G. Hyaluronan and its potential role in periodontal healing. Dent Update. 2002;29:144–8. doi: 10.12968/denu.2002.29.3.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pirnazar P, Wolinsky L, Nachnani S, Haake S, Pilloni A, Bernard GW. Bacteriostatic effects of hyaluronic acid. J Periodontol. 1999;70:370–4. doi: 10.1902/jop.1999.70.4.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eick S, Renatus A, Heinicke M, Pfister W, Stratul SI, Jentsch H. Hyaluronic Acid as an adjunct after scaling and root planing: A prospective randomized clinical trial. J Periodontol. 2013;84:941–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.2012.120269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pilloni A, Annibali S, Dominici F, Di Paolo C, Papa M, Cassini MA, et al. Evaluation of the efficacy of an hyaluronic acid-based biogel on periodontal clinical parameters. A randomized-controlled clinical pilot study. Ann Stomatol (Roma) 2011;2:3–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johannsen A, Tellefsen M, Wikesjö U, Johannsen G. Local delivery of hyaluronan as an adjunct to scaling and root planing in the treatment of chronic periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2009;80:1493–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.090128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fawzy El-Sayed KM, Dahaba MA, Aboul-Ela S, Darhous MS. Local application of hyaluronan gel in conjunction with periodontal surgery: A randomized controlled trial. Clin Oral Investig. 2012;16:1229–36. doi: 10.1007/s00784-011-0630-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pistorius A, Martin M, Willershausen B, Rockmann P. The clinical application of hyaluronic acid in gingivitis therapy. Quintessence Int. 2005;36:531–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gontiya G, Galgali SR. Effect of hyaluronan on periodontitis: A clinical and histological study. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2012;16:184–92. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.99260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]