Abstract

Aim:

The aim of this study was to determine whether the addition of an autologous platelet rich fibrin (PRF) membrane to a coronally advanced flap (CAF) would improve the clinical outcome in terms of root coverage, in the treatment of isolated gingival recession.

Materials and Methods:

Systemically healthy 20 subjects each with single Miller's class I or II buccal recession defect were randomly assigned to control (CAF) or test (CAF + PRF) group. Clinical outcome was determined by measuring the following clinical parameters such as recession depth (RD), recession width (RW), probing depth (PD), clinical attachment level (CAL), width of keratinized tissue (WKT), gingival thickness (GTH), plaque index (PI), and gingival index (GI) at baseline, 3rd, and 6th month postsurgery.

Results:

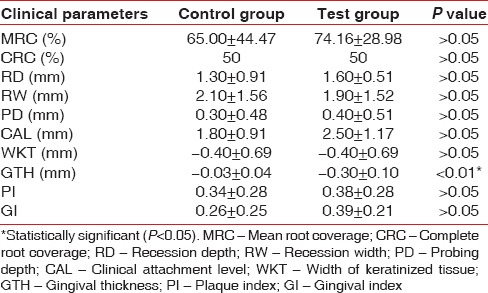

The root coverage was 65.00 ± 44.47% in the control group and 74.16 ± 28.98% in the test group at 6th month, with no statistically significant difference between them. Similarly, CAL, PD, and WKT between the groups were not statistically significant. Conversely, there was statistically significant increase in GTH in the test group.

Conclusion:

CAF is a predictable treatment for isolated Miller's class I and II recession defects. The addition of PRF to CAF provided no added advantage in terms of root coverage except for an increase in GTH.

Keywords: Coronally advanced flap, gingival recession, gingival thickness, platelet rich fibrin, recession coverage

INTRODUCTION

Historically periodontal therapy has been directed primarily at the elimination of disease and maintenance of a functional, healthy dentition and supporting tissues. More recently however it has become increasingly focused on esthetic outcomes, which extend beyond tooth replacement and tooth color to include the soft tissues framing the dentition.[1]

One of the most common esthetic concerns associated with the periodontal tissue is gingival recession. It is the displacement of the gingival margin apical to cemento-enamel junction (CEJ), resulting in higher incidence of attachment loss, root caries, and root hypersensitivity. Its development has been frequently associated with periodontal disease, traumatic tooth brushing, frenal pull, and tooth malposition.[2,3,4,5]

Surgical treatments like free graft and pedicle flap are indicated when the gingival recession causes functional or esthetic problems. With the use of free soft tissue grafts, the esthetic results were often unsatisfactory and also required a second surgical site. Pedicle flaps without tissue grafts have also been used successfully for recession coverage in different modifications.[6,7]

Among these, coronally advanced flap (CAF) technique have shown more predictable recession coverage with apparently satisfactory esthetic results.[7] Nevertheless, CAF when used alone is unstable on long-term, in spite of having the advantage of low morbidity.[8] Furthermore, it does not always result in the regeneration of attachment apparatus such as cementum, periodontal ligament (PDL), and alveolar bone, which is a major risk factor in recurrence of gingival recession. Therefore, CAF have been frequently combined with various regenerative materials aiming at attaining both regeneration of functional attachment apparatus and root coverage.

Several regenerative materials such as guided tissue regeneration membranes,[9,10] enamel matrix proteins derivatives,[11] alloderm,[12] living tissue-engineered human fibroblast derived dermal substitute[13] have been combined with CAF in the treatment of gingival recession and have reported good clinical outcomes. Although these regenerative materials are still used today, the introduction of autologous biomimetic agents like platelet concentrates has given new promise for the better clinical outcomes in periodontal therapy.[14,15]

Platelet rich fibrin (PRF) is an autologous biomimetic agent that belongs to second generation platelet concentrate system, with simplified processing, which requires neither anticoagulant nor bovine thrombin for its preparation.[14] It has a fibrin three dimensional matrices polymerized in a specific structure with the incorporation of platelets, leukocytes, growth factors, and circulating stem cells.[16]

Platelet rich fibrin is considered to be a healing biomaterial, which is now used in periodontal plastic and implant surgical procedures to enhance bone regeneration and soft tissue wound healing. Thus, this study was conducted to clinically evaluate the effectiveness of autologous PRF membrane with CAF in the treatment of isolated gingival recession.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A total of 20 subjects aging 21-47 years including 18 males and 2 females attending the Department of Periodontics were recruited for the study. Institutional Ethical Committee approval was obtained. The procedures were explained to patients and written informed consent was obtained.

The inclusion criteria was the presence of Miller's class I or II (confirmed by radiographic analysis of involved tooth) recession defect in maxillary or mandibular incisors, canines, or premolars. The patients should be above 18 years old with an ability to maintain good oral hygiene (full-mouth plaque index (PI) <20%).[17]

Patients with any of the following were excluded: (1) Systemic illness known to affect the outcome of periodontal therapy, (2) allergic to medications, (3) pregnant and lactating women, (4) use of tobacco in any form, (5) patients under anticoagulation treatment, bleeding disorder, and (6) patients with caries or restorations in the area to be treated.[18]

The subjects were randomly assigned to two treatment groups by drawing envelops, including notes stating either test or control. The control group included ten defects (six maxillary teeth, four mandibular teeth), which were treated with CAF, whereas the test group with 10 defects (four maxillary teeth and six mandibular teeth) was treated with CAF with PRF.

For all the enrolled patients routine radiographic and blood investigations were done. The initial therapy consisted of scaling, root planing, oral hygiene instructions, and occlusal adjustments as indicated. Three weeks following phase I therapy, a periodontal re-evaluation was performed. All clinical parameters were recorded by a single examiner at baseline (BL), 3rd, and 6th month who is masked about the treatment groups.

In order to standardize probe placement and angulations, during measurement an acrylic stent was fabricated for each surgical site with vertical groove placed at the mid-buccal region. All measurements were obtained with a standardized Williams graduated probe (Hu-Friedy) and rounded up to the nearest millimeter.

The following are the parameters measured: (1) Probing depth (PD), (2) clinical attachment level (CAL), (3) recession depth (RD), (4) recession width (RW), (5) width of keratinized tissue (WKT), and (6) gingival thickness (GTH) was measured 3 mm below the gingival margin at the attached gingiva or the alveolar mucosa using a #15 endodontic reamer with a silicon disk stop. The mucosal surface was pierced at a 90° angle with slight pressure until hard tissue was reached. The silicon stop on the reamer was slid until it was in close contact with the gingiva. After removal of the reamer, the distance between the tip of the reamer and the inner border of the silicon stop was measured to the nearest millimeter using a caliper with 0.1 mm calibration.[18] (7) PI was recorded according to Silness and Loe (1964). (8) Gingival index (GI) was recorded according to Loe and Silness (1963). (9) Percentage of mean root coverage (MRC %) was calculated as ([RD preoperative - RD postoperative]/RD preoperative) × 100%.[17]

The PRF was prepared following the protocol developed by Choukroun et al.[19] Prior to surgery, 10 ml of intravenous blood (by a venipuncture of the antecubital vein) was collected in test tubes without anticoagulant and immediately centrifuged at 3000 revolutions/min for 10 min. At the end of centrifugation, three layers were seen, the top layer containing supernatant serum, the fibrin clot at the middle layer, and the bottom layer containing the red blood corpuscles (RBC). The fibrin clot was easily separated from the RBC base (preserving a small RBC layers) using sterile tweezers and scissors, and placed in a sterile metal cup and was left aside to release their serum slowly into the metal cup (soft exudate extraction).[20]

All surgical procedures as well as PRF preparation were done by a single investigator. Both test and control groups were treated with CAF using the technique described by Pini-Prato et al.[21] except for the placement of PRF in the test group. After preoperative oral antisepsis the surgical area was anaesthetized, the exposed root surface was scaled and planed followed by root conditioning with a fresh tetracycline (125 mg tetracycline/ml of saline) [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Preoperative view at (a) control site (#11); (b) test site (#23). Note the Miller's class I gingival recession

A full thickness trapezoidal flap was elevated on the buccal aspect of the tooth being treated, using an intrasulcular incision extending horizontally to dissect the buccal aspect of adjacent papilla and two vertical incisions starting from its mesial and distal extremities extending beyond the muco-gingival junction. This is followed apically with a partial thickness dissection. The papillae adjacent to the involved tooth were de-epithelialized.

At the test sites, previously prepared PRF membrane was placed over the recession defect, just coronal to the CEJ and held in position with single independent sling suture [Figure 2]. The serum exudate from the fibrin clot was applied over the surgical site. The control groups received no further treatment. Flaps were then coronally advanced, with its margin located on the enamel, interposed with the PRF membrane and sutured using nonresorbable sutures.[22] Gentle pressure was applied at the surgical site with moistened gauze to achieve hemostasis and a close adaptation of the flap followed by periodontal dressing.

Figure 2.

Operative view showing flap elevation with platelet rich fibrin membrane sutured over the test site (#23)

All patients were prescribed with antibiotics and analgesics. Post-operative instructions were given and patients were informed to report after 10 days for suture removal.[18] Professional scaling and oral hygiene reinforcement were provided at each follow-up visit whenever indicated till 6th month [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Postoperative view after 6th month, note the root coverage at (a) control site (#11); (b) test site (#23)

Statistical analysis

A subject level analysis was performed for each parameter. The significance of the difference within and between groups before and after treatment was evaluated with paired sample t-test. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05. The statistical analysis was performed using commercially available software (SPSS for Windows version 16.0).

RESULTS

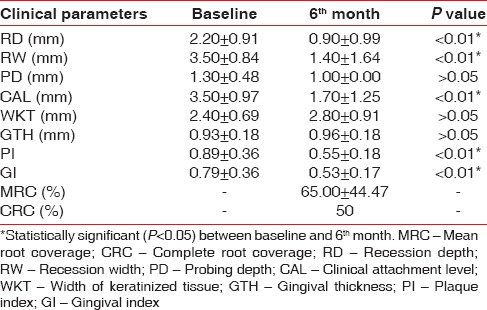

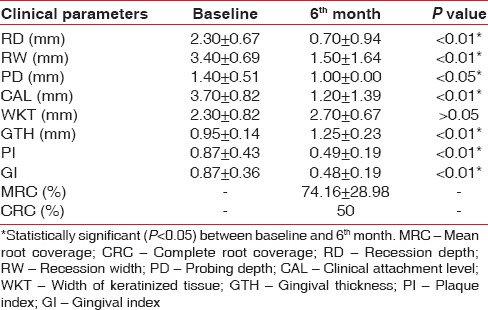

All subjects who were enrolled completed the study. The comparison of clinical parameters between the groups at BL showed no statistically significant difference [Table 1]. The comparison of clinical parameters within the control and test group at BL and 6th month are summarized in Tables 2 and 3. The comparison of clinical parameters between the control and test group at 6th month is shown in Table 4.

Table 1.

Comparison of different clinical parameters between control and test groups at baseline

Table 2.

Comparison of different clinical parameters within control group at baseline and 6th month

Table 3.

Comparison of different clinical parameters within test group at baseline and 6th month

Table 4.

Comparison of different clinical parameters between control and test groups at 6th month

DISCUSSION

Platelet rich fibrin has been claimed to enhance soft tissue healing, promote initial stabilization, revascularization of flaps and grafts in root coverage.[18] However, limited evidence is currently available verifying these claims. Therefore, this study was designed to investigate the effects of PRF on CAF root coverage procedure. In this study, the clinical outcomes were evaluated over a period of 6 months, which is sufficient to evaluate the stability of the gingival margin after a CAF.[23] The mean PI and GI score in this study showed a marked improvement (P < 0.05) for both treatment groups [Tables 2 and 3]. This might be due to the reinforcement of oral hygiene and regular monitoring of the patients undergoing periodontal therapy.[24]

The MRC obtained in the control group at 3rd month (data not shown) reduced at the end of 6th month follow-up [Table 2], which is similar to Pini-Prato et al.[25] who attributed it to the thin marginal tissue and amount of keratinized tissue achieved postsurgically, leading to a possible relapse of the gingival margin during the maintenance phase.

MRC obtained in the test group was stable between 3rd (data not shown) and 6th month [Table 3] when PRF was used. This is in agreement with Shepherd et al.[26] where no change in the MRC postoperatively was observed, between 2nd and 4th month follow-up, when PRP (platelet rich plasma) was used. This may suggest that, platelet concentrates promotes more rapid attachment to the tooth with stable result. Furthermore, it was proposed that PRF as a healing material stimulates the gingival connective tissue on its whole surface with growth factors. Moreover, the fibrin matrix itself shows mechanical adhesive properties and biologic functions like fibrin glue, which maintains the flap in a high and stable position, enhances neoangiogenesis, reduces necrosis, resulting in maximum recession coverage.[27] As an interpositional matrix PRF layers prevents the early invagination of the gingival epithelium.[27] In this study, although clinically significant, there was no statistically significant (P > 0.05) difference in MRC between the groups at 3rd and 6th month [Table 4].

However, an earlier study by Aroca et al.[18] have reported an inferior recession coverage using PRF membrane, when compared with CAF alone in multiple recession defects. This inferior result was attributed to the use of a single PRF membrane for a multiple recession defect.[27] Since PRF membrane is an inhomogeneous matrix with leukocytes and platelet aggregates concentrated within different ends, it is appropriate to use more than one membrane placed in an opposite direction to have a uniform effect over the entire recession defects.[28] The present study involved the treatment of isolated recession defects and hence a single PRF membrane was used.

Both the treatment groups resulted in a statistically significant gain in CAL and reduction in PD (in test group) [Tables 2 and 3]; however, it was not significant between the groups at 6th month (P > 0.05) [Table 4]. Both the groups showed a nonsignificant increase in mean WKT when compared both within and between the groups [Tables 2–4].

The control group showed a nonsignificant GTH increase of 0.03 ± 0.04 mm [Table 2] which is similar to other studies.[18] Interestingly, the addition of PRF to CAF in test group resulted in a 0.30 ± 0.10 mm GTH increase, which was statistically significant when compared both within and between the groups [Tables 3 and 4] and concurs well with Aroca et al. study.[18] The increase in soft tissue thickness might be due to the influence of growth factors from PRF membrane on the proliferation of gingival and PDL fibroblasts or to a spacing effect of PRF membrane.[18] This gain in GTH should be considered clinically significant since abundant empirical evidence suggests that thick tissue, resists trauma and subsequent recession, enables tissue manipulation, promotes creeping attachment and exhibits less clinical inflammation.[29] In agreement with this Woodyard et al.[12] reported a greater number of sites with CRC when treated with Alloderm, which increased the marginal soft tissue thickness.

Similarly, Pini-Prato et al.[25] have reported a creeping attachment post-surgically at sites where GTH was increased using connective tissue graft. Contradicting to these Wenstrom and Zucchelli[30] reported that the stability of the gingival margin obtained post-surgically is determined by an altered tooth brushing technique, which reduces tissue trauma rather than to the gingival dimensions. However, the proper evaluation of the effect of GTH on recession coverage stability (i.e. no change, further recession, or creeping attachment) necessitates more investigations with greater follow-up visits.

Thus, in this study, both treatment techniques resulted in a favorable clinical outcome in terms of root coverage obtained. While comparing the two groups, there was no statistically significant difference for any of the clinical parameters except for an increase in GTH in the test group. Thus, future studies with larger sample size and greater follow-up period are needed to determine the advantage of using PRF in CAF for root coverage. Factors such as PRF consistency, platelet concentration were not tested in this study, which may have affected the final clinical outcome. In addition, no histologic evaluation was performed to assess the type of healing. Therefore, the effect of PRF on the establishment of a connective tissue attachment remains to be determined.

CONCLUSION

The ease of applying PRF in the dental clinic and its beneficial outcomes, including reduction of bleeding and rapid healing, holds promise even though the mechanisms involved are still poorly understood. More well-designed and properly controlled studies are needed to provide solid evidence of PRF's capacity for and impact on wound healing, soft tissue reconstruction and augmentation procedures, especially in periodontal therapy.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kontovazainitis G, Griffin TJ, Cheung WS. Treatment of gingival recession using platelet concentrate with a bioabsorbable membrane and coronally advanced flap: A report of two cases. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2008;28:301–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zucchelli G, Amore C, Sforza NM, Montebugnoli L, De Sanctis M. Bilaminar techniques for the treatment of recession-type defects. A comparative clinical study. J Clin Periodontol. 2003;30:862–70. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2003.00397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Susin C, Haas AN, Oppermann RV, Haugejorden O, Albandar JM. Gingival recession: Epidemiology and risk indicators in a representative urban Brazilian population. J Periodontol. 2004;75:1377–86. doi: 10.1902/jop.2004.75.10.1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheung WS, Griffin TJ. A comparative study of root coverage with connective tissue and platelet concentrate grafts: 8-month results. J Periodontol. 2004;75:1678–87. doi: 10.1902/jop.2004.75.12.1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kassab MM, Cohen RE. The etiology and prevalence of gingival recession. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134:220–5. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2003.0137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paolantonio M. Treatment of gingival recessions by combined periodontal regenerative technique, guided tissue regeneration, and subpedicle connective tissue graft. A comparative clinical study. J Periodontol. 2002;73:53–62. doi: 10.1902/jop.2002.73.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hägewald S, Spahr A, Rompola E, Haller B, Heijl L, Bernimoulin JP. Comparative study of Emdogain and coronally advanced flap technique in the treatment of human gingival recessions. A prospective controlled clinical study. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29:35–41. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2002.290106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jankovic S, Aleksic Z, Milinkovic I, Dimitrijevic B. The coronally advanced flap in combination with platelet-rich fibrin (PRF) and enamel matrix derivative in the treatment of gingival recession: A comparative study. Eur J Esthet Dent. 2010;5:260–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee EJ, Meraw SJ, Oh TJ, Giannobile WV, Wang HL. Comparative histologic analysis of coronally advanced flap with and without collagen membrane for root coverage. J Periodontol. 2002;73:779–88. doi: 10.1902/jop.2002.73.7.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pini Prato G, Tinti C, Vincenzi G, Magnani C, Cortellini P, Clauser C. Guided tissue regeneration versus mucogingival surgery in the treatment of human buccal gingival recession. J Periodontol. 1992;63:919–28. doi: 10.1902/jop.1992.63.11.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pilloni A, Paolantonio M, Camargo PM. Root coverage with a coronally positioned flap used in combination with enamel matrix derivative: 18-month clinical evaluation. J Periodontol. 2006;77:2031–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.050390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woodyard JG, Greenwell H, Hill M, Drisko C, Iasella JM, Scheetz J. The clinical effect of acellular dermal matrix on gingival thickness and root coverage compared to coronally positioned flap alone. J Periodontol. 2004;75:44–56. doi: 10.1902/jop.2004.75.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilson TG, Jr, McGuire MK, Nunn ME. Evaluation of the safety and efficacy of periodontal applications of a living tissue-engineered human fibroblast-derived dermal substitute. II. Comparison to the subepithelial connective tissue graft: A randomized controlled feasibility study. J Periodontol. 2005;76:881–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.6.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choukroun J, Diss A, Simonpieri A, Girard MO, Schoeffler C, Dohan SL, et al. Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF): A second-generation platelet concentrate. Part IV: Clinical effects on tissue healing. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:e56–60. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Su CY, Kuo YP, Tseng YH, Su CH, Burnouf T. In vitro release of growth factors from platelet-rich fibrin (PRF): A proposal to optimize the clinical applications of PRF. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;108:56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dohan DM, Choukroun J, Diss A, Dohan SL, Dohan AJ, Mouhyi J, et al. Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF): A second-generation platelet concentrate. Part II: Platelet-related biologic features. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:e45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang LH, Neiva RE, Soehren SE, Giannobile WV, Wang HL. The effect of platelet-rich plasma on the coronally advanced flap root coverage procedure: A pilot human trial. J Periodontol. 2005;76:1768–77. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.10.1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aroca S, Keglevich T, Barbieri B, Gera I, Etienne D. Clinical evaluation of a modified coronally advanced flap alone or in combination with a platelet-rich fibrin membrane for the treatment of adjacent multiple gingival recessions: A 6-month study. J Periodontol. 2009;80:244–52. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.080253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choukroun J, Adda F, Schoeffler C, Vervelle A. An opportunity in perio-implantology: The PRF (in French) Implantodontie. 2001;42:55–62. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dohan Ehrenfest DM, Del Corso M, Diss A, Mouhyi J, Charrier JB. Three-dimensional architecture and cell composition of a Choukroun's platelet-rich fibrin clot and membrane. J Periodontol. 2010;81:546–55. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.090531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pini-Prato G, Baldi C, Pagliaro U, Nieri M, Saletta D, Rotundo R, et al. Coronally advanced flap procedure for root coverage. Treatment of root surface: Root planning versus polishing. J Periodontol. 1999;70:1064–76. doi: 10.1902/jop.1999.70.9.1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Allen EP, Miller PD., Jr Coronal positioning of existing gingiva: Short term results in the treatment of shallow marginal tissue recession. J Periodontol. 1989;60:316–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.1989.60.6.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheng YF, Chen JW, Lin SJ, Lu HK. Is coronally positioned flap procedure adjunct with enamel matrix derivative or root conditioning a relevant predictor for achieving root coverage. A systemic review? J Periodontal Res. 2007;42:474–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2007.00971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gürgan CA, Oruç AM, Akkaya M. Alterations in location of the mucogingival junction 5 years after coronally repositioned flap surgery. J Periodontol. 2004;75:893–901. doi: 10.1902/jop.2004.75.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pini-Prato GP, Cairo F, Nieri M, Franceschi D, Rotundo R, Cortellini P. Coronally advanced flap versus connective tissue graft in the treatment of multiple gingival recessions: A split-mouth study with a 5-year follow-up. J Clin Periodontol. 2010;37:644–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2010.01559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shepherd N, Greenwell H, Hill M, Vidal R, Scheetz JP. Root coverage using acellular dermal matrix and comparing a coronally positioned tunnel with and without platelet-rich plasma: A pilot study in humans. J Periodontol. 2009;80:397–404. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.080438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Del Corso M, Sammartino G, Dohan Ehrenfest DM. Re: “Clinical evaluation of a modified coronally advanced flap alone or in combination with a platelet-rich fibrin membrane for the treatment of adjacent multiple gingival recessions: A 6-month study”. J Periodontol. 2009;80:1694–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.090253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leknes KN, Amarante ES, Price DE, Bøe OE, Skavland RJ, Lie T. Coronally positioned flap procedures with or without a biodegradable membrane in the treatment of human gingival recession. A 6-year follow-up study. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32:518–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hwang D, Wang HL. Flap thickness as a predictor of root coverage: A systematic review. J Periodontol. 2006;77:1625–34. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.060107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wennström JL, Zucchelli G. Increased gingival dimensions. A significant factor for successful outcome of root coverage procedures?. A 2-year prospective clinical study. J Clin Periodontol. 1996;23:770–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1996.tb00608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]