Abstract

The peripheral ossifying fibroma (POF) is a relatively uncommon, reactive gingival overgrowth usually composed of cellular fibroblastic tissue containing one or more mineralized tissues, namely bone, cementum-like material, or dystrophic calcification. The aetiology and pathogenesis of POF are yet not clear, but some authors have hypothesized a reaction originating from the periodontal ligament, as a result of irritating agents such as dental calculus, plaque, orthodontic appliances, and ill-fitting restorations. The aim of our study was to report the clinicopathologic features of a case series of POF from a single Italian institution. A total of 27 cases were collected over an 18-year period. Detailed relevant medical history, clinical and histological information were recorded for each patient. The age range of patients (m = 6; f = 21) was 17.2-80.1 years with a mean of 42.9 ± 18.1 years. Occurrence of the lesion in the mandibular and maxillary arches was similar, and 67.0% occurred in the incisor-cuspid region. The lesions ranged in size from 0.3 to 5.0 cm (mean, 1.3 cm ± 1.1 cm). All the different types of mineralization were present, with higher prevalence of lamellar bone. The lesions were treated by surgical excision and four lesions in three patients recurred after surgery. Surgeons should consider the high recurrence rate of POF and remove the lesion down to the bone involving also the adjacent periosteum and the periodontal ligament. Professional prophylaxis should precede any surgical procedure, and periodical dental hygiene recalls are important in order to remove any possible irritating factor.

Keywords: Epulis, gingival diseases, laser, oral surgical procedures

INTRODUCTION

Peripheral ossifying fibroma (POF) is a relatively uncommon, probably reactive gingival overgrowth. POFs consist of one or more mineralized tissues, including bone, cementum-like material, or dystrophic calcification[1] within a matrix of cellular fibroblastic tissue.

Females are more commonly affected than males, and the anterior maxilla is the most common site of occurrence.[2] POFs are diagnosed at any age, with a peak in the second decade of life.

Clinically, POF usually presents as a solitary, slow-growing, pedunculated or sessile, nodular mass. To the best of our knowledge, a unique case of multicentric manifestation has been reported.[3] The surface mucosa can be smooth or ulcerated and pink to red in colour.[2] Migration of teeth with interdental bone destruction has been reported in some cases.[4] POFs usually measure <1.5 cm in diameter even though lesions of 6 cm and 9 cm in diameter are recorded.[5,6] On the clinical level, differential diagnoses include peripheral giant cell granuloma, pyogenic granuloma, and fibrous epulis.[1]

The etiology and pathogenesis of POF are not yet clear. Some authors have hypothesized a reactive lesion originating from the periodontal ligament as a result of irritating agents such as dental calculus, plaque, orthodontic appliances, and ill-fitting restorations.[1]

The presence of oxytalan fibers interspersed among the calcified structures,[7] the almost exclusive occurrence on the gingiva, and the age distribution inversely correlating with the number of lost permanent teeth[2] support the hypothesis of an origin from the periodontal ligament. Moreover, the fibrocellular response of POF is similar to that observed in other reactive gingival lesions originating from the periodontal ligament[8] (e.g. fibrous epulis).

A possible hormonal influence has also been considered mainly because POFs are rare in prepubertal patients.[9] However, a recent study failed to demonstrate the expression of estrogen or progesterone receptors in the proliferating cellular component.[8]

Regezi et al. found a large number of XIIIa+ cells, a subset of monocyte/macrophages, in POF and in other oral fibrovascular reactive lesions; it was hypothesized that these dendrocytes could play a distinct pathogenic role.[10]

An important clinical aspect of POF is the high recurrence rate, which ranges from 8% to 45%.[11]

The purpose of this study is to report the clinicopathologic features of POFs from a single Italian institution, with special emphasis on the histomorphologic features of mineralized tissues.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A total of 27 cases of POF, diagnosed over an 18-year period (1992-2010), were retrieved from the archives of the Unit of Oral Pathology, Oral Medicine and Laser-assisted Oral Surgery of the Academic Hospital of Parma. Medical history and clinical and histological information were obtained for each patient from referral letters, medical dossiers, biopsy request forms, and histopathological reports. Lesions were subclassified according to the following anatomic subsites: (1) Incisor/canine (mesial of central incisor to distal of the canine); (2) premolar/molar (mesial of first premolar to distal of third molar area). A lesion encompassing more than one region was included within the subsite it occupied most.

Light microscopic examination of sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin was performed in each case. As proposed by Buchner and Hansen,[2] the different mineralized tissues were divided into following three groups:

Woven and lamellar bone trabeculae

Cementum-like formations: Mineralized bodies that appear circumscribed, amorphous, almost a cellular, basophilic (but sometimes eosinophilic) and range in size from small to very large globules

Dystrophic calcifications: Granular foci of mineralization, which present as a cluster of very small basophilic granules, tiny globules and small, solid irregular masses.

Data were summarized as means and standard deviations.

RESULTS

Peripheral ossifying fibromas (27 cases) comprised 1.1% of all the 2541 oral biopsies performed in our institution from January 1992 to January 2010 and 6.7% of all gingival lesions (n = 403). All lesions reported here were surgically removed from 23 patients.

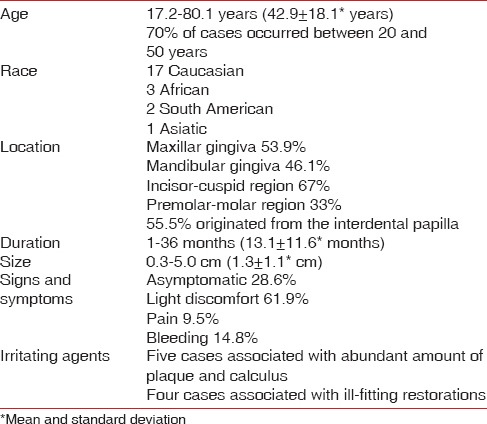

Age at diagnosis ranged from 17.2 to 80.1 years with a mean of 42.9 ± 18.1 years. The highest incidence of lesions was in the third decade (7 cases). About 70% of the cases occurred in patients between 20 and 50 years of age. Six patients were male and 21 were female. Three lesions (11.1%) occurred in African patients [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical features of patients affected by peripheal ossifying fibroma

Data on the location of the lesion was available for 25 cases. Occurrence of the lesions in the lower (53.9%) and upper jaw (46.1%) was similar. Sixteen lesions (67.0%) occurred in the incisor-cuspid region and 8 (33.0%) in the premolar-molar region.

Lesions were exophytic, pedunculated or sessile, nodular masses, and all of them were on the gingiva except for 1 case, which occurred on the retromolar pad. In 15 cases, the clinicians reported an origin from interdental papilla.

Time of onset of lesions was known for 18 cases and ranged from 1 to 36 months (mean, 13.1 ± 11.6 months).

Color ranged from pink to slightly red or bright red, and the surface was described as ulcerated in 2 cases.

Lesions ranged in size from 0.3 to 5.0 cm (mean, 1.3 ± 1.1 cm).

Six patients reported that the lesion was asymptomatic, 13 referred a light discomfort and two patients experienced pain. Bleeding was reported in 4 cases.

In 5 cases, the lesion was associated with presence of significant calculus and dental plaque [Figure 1] and in 4 cases with an ill-fitting fixed prosthesis [Figure 2]. In 3 cases, it was recorded that no irritating agents were present.

Figure 1.

Peripheral ossifying fibroma associated with significant calculus

Figure 2.

Peripheal ossifying fibroma associated with an ill-fitting fixed prosthesis

Radiographic findings highlighted normal underlying bone structure. The lesion was cupping out of the alveolar bone in 1 case.

All lesions were treated by surgical excision after professional prophylaxis. The surgical technique was known in 17 cases: Four lesions were excised with the use of cold blade (traditional surgery), nine lesions were removed with Nd: YAG laser (laser parameters: 3 W, 40 Hz - 300 μm fiber diameter) and in 4 the quantic molecular resonance (QMR) scalpel was used. Independently of the surgical technique, a scaling of the adjacent dental roots was performed.

Three patients reported that the lesion was previously removed in another institution before recurrence and presentation to our center.

Four lesions in three patients recurred after excision in our clinic. In the first of these three patients the lesions was removed by a surgeon-in-training and then recurred after 5 months, probably for inadequate excision. An experienced surgeon then treated the patient, which remained free of the disease for 6 months.

In the second patient, the lesion recurred 2 times, the first time after 24 months. The patient underwent another excision, but a POF reappeared in the same site after 54 months. The patient was re-operated and remained free from disease for 7 months. In this patient, the lesion was associated with an ill-fitting anterior bridge, which the patient denied to replace. In the third patient, the lesions recurred after 2 years in absence of evident irritating agents.

Recurrence rate in the present series was 30.4%.

In 8 cases (29.6%), the surface of the lesion was partially or completely ulcerated, while in 19 cases (70.4%) the surface was intact; both in ulcerated and nonulcerated lesions an ortho/parakeratinized and often hyperplastic epithelium was present.

The subepithelial tissue (in nonulcerated lesions) or the zone beneath the surface ulceration (in ulcerated lesions) was composed of fibroblastic connective tissue with varying degrees of chronic inflammatory infiltrate, mostly lymphocytes, and plasma cells. The amount of collagen, as well as the grade of cellularity, varied in different specimens from limited to very pronounced. The nuclei of the fibroblasts had a round-to-oval to spindle-shaped morphology and sometimes were arranged in small fascicles. Dispersed dystrophic calcifications represented by clusters of basophilic granules were noted in many specimens.

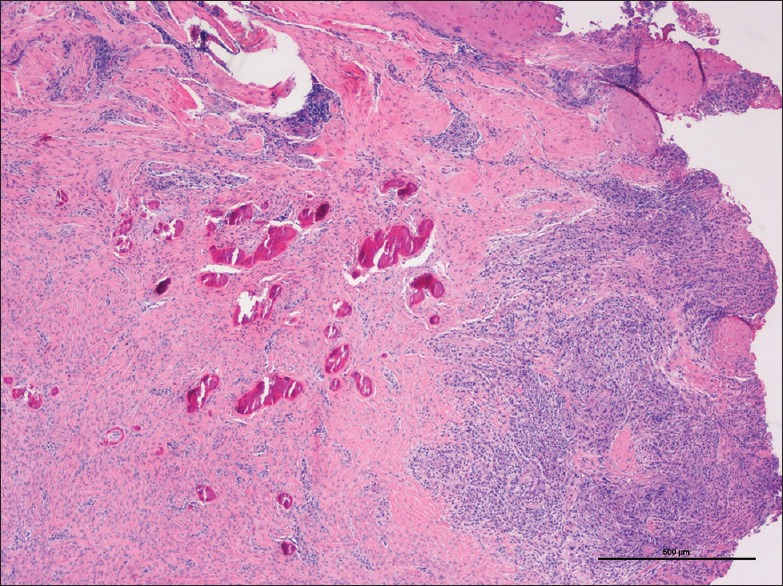

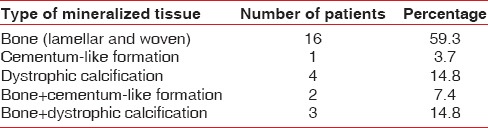

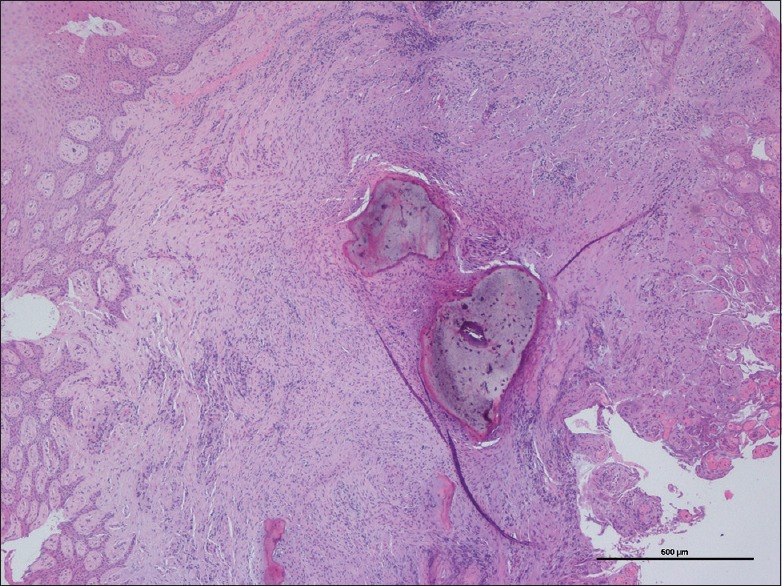

In the deeper parts of some lesions, the connective tissue was more collagenized and the inflammatory infiltrate was diminished. In this area, osteogenesis was often well-represented. In general, vascularity, composed by scattered small capillaries, decreased from the periphery to the center of the lesion. The prevalence of the different types of mineralization [Figures 3–5] is depicted in Table 2.

Figure 3.

Microscopic aspect of mineralized tissue within peripheal ossifying fibroma: Lamellar bone (H and E, ×4)

Figure 5.

Microscopic aspect of mineralized tissue within peripheal ossifying fibroma: Dystrophic calcification (H and E, ×4)

Table 2.

Prevalence of mineralized tissue in 27 cases of peripheal ossifying fibroma

Figure 4.

Microscopic aspect of mineralized tissue within peripheal ossifying fibroma: Cementum-like formation (H and E, ×4)

DISCUSSION

Peripheral ossifying fibroma is a benign proliferation almost exclusively affecting the gingiva, although a case of POF localized on lingual mucosa has been recorded.[12]

Other terms used in the past to define this lesion were peripheral fibroma with calcification, ossifying fibrous epulis, and calcifying fibroblastic granuloma.[11] POF should be distinguished from the (central) ossifying fibroma, which is not the central counterpart of POF but is instead a true neoplasm with significant growth potential.[1] (Central) ossifying fibroma occurs mainly in females in the third and fourth decade of life, and the mandible is more involved than the maxilla. It consists of fibrous tissue that exhibits varying degrees of cellularity and contains mineralized materials.

Apparently, the name POF represents a misnomer and its use could evoke some confusion. In fact, the term fibroma etymologically means tumor of fibrous connective tissue (from Latin fibra, “fiber” + Greek oma, “tumor”), but POF is not considered a true neoplasm.[13]

This study reports a series of 27 POF treated at the Academic Hospital of Parma from 1992 to 2010. In their large series, Eversole and Rovin; Buchner and Hansen and Kenney et al. reported a peak of prevalence of POF in the second decade.[2,9,14] In our patient population, the highest prevalence of lesions was in the third decade. This difference from data published in the literature could be explained by the fact that some patients presented with a recurrent lesion after a first manifestation occurred some years before.

Surgeons should consider the high recurrence rate of POF and remove the lesion down to bone involving also the adjacent periosteum and the periodontal ligament. If the lesion is localized in an esthetic area, reconstructive surgery should be performed to repair the defect.[15] Extraction of neighboring teeth is seldom required. The use of techniques different from traditional surgery with cold blade, such as Nd: YAG laser and QMR scalpel add some advantages (i.e., reduction of intraoperatory bleeding, reduction of postoperative discomfort, improved healing through biostimulation).[16,17] It is still not demonstrated if the surgical technique influences the rate of recurrence, even if better control of the surgical field due to the hemostatic properties of Nd: YAG laser and QMR scalpel could help the operator in the complete removal of the lesion.

In the literature, it is not clear how long should be the follow-up to define a patient is cured.

The rapid recurrence of the lesion in one of our cases could be related to its incomplete excision.

To minimize the possibility of recurrence, it is necessary to remove all putative risk factors, including plaque, calculus and plaque-retentive restorations.

In some of our patients, clear irritating factors were lacking. One of the three patients with a recurrent lesion after surgical removal in our institution had excellent oral hygiene and did not wear dental, orthodontic appliances or have ill-fitting restorations. The time between the surgery and the recurrence (2 years) was sufficiently long enough to exclude the presence of residual pathologic tissue left from the first intervention. Some doubts on the reactive nature of POF could arise from this observation. The etiopathogenesis of this lesion is still not clear, and further studies are needed to elucidate the mechanisms of POF development.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Bouquot JE. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2002. Soft tissue tumors; pp. 451–2. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buchner A, Hansen LS. The histomorphologic spectrum of peripheral ossifying fibroma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1987;63:452–61. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(87)90258-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumar SK, Ram S, Jorgensen MG, Shuler CF, Sedghizadeh PP. Multicentric peripheral ossifying fibroma. J Oral Sci. 2006;48:239–43. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.48.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yadav R, Gulati A. Peripheral ossifying fibroma: A case report. J Oral Sci. 2009;51:151–4. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.51.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bodner L, Dayan D. Growth potential of peripheral ossifying fibroma. J Clin Periodontol. 1987;14:551–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1987.tb00998.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poon CK, Kwan PC, Chao SY. Giant peripheral ossifying fibroma of the maxilla: Report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995;53:695–8. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(95)90174-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wright BA, Jennings EH. Oxytalan fibers in peripheral odontogenic fibromas. A histochemical study of eighteen cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1979;48:451–3. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(79)90077-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.García de Marcos JA, García de Marcos MJ, Arroyo Rodríguez S, Chiarri Rodrigo J, Poblet E. Peripheral ossifying fibroma: A clinical and immunohistochemical study of four cases. J Oral Sci. 2010;52:95–9. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.52.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kenney JN, Kaugars GE, Abbey LM. Comparison between the peripheral ossifying fibroma and peripheral odontogenic fibroma. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989;47:378–82. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(89)90339-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Regezi JA, Nickoloff BJ, Headington JT. Oral submucosal dendrocytes: Factor XIIIa+and CD34+dendritic cell populations in normal tissue and fibrovascular lesions. J Cutan Pathol. 1992;19:398–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1992.tb00612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cuisia ZE, Brannon RB. Peripheral ossifying fibroma – A clinical evaluation of 134 pediatric cases. Pediatr Dent. 2001;23:245–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thierbach V, Quarcoo S, Orlian AI. Atypical peripheral ossifying fibroma. A case report. N Y State Dent J. 2000;66:26–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Subramanyam RV. Misnomers in oral pathology. Oral Dis. 2010;16:740–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2010.01695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eversole LR, Rovin S. Reactive lesions of the gingiva. J Oral Pathol. 1972;1:30–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walters JD, Will JK, Hatfield RD, Cacchillo DA, Raabe DA. Excision and repair of the peripheral ossifying fibroma: A report of 3 cases. J Periodontol. 2001;72:939–44. doi: 10.1902/jop.2001.72.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vescovi P, Manfredi M, Merigo E, Fornaini C, Rocca JP, Nammour S, et al. Quantic molecular resonance scalpel and its potential applications in oral surgery. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;46:355–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parker S. Lasers and soft tissue: ‘fixed’ soft tissue surgery. Br Dent J. 2007;202:247–53. doi: 10.1038/bdj.2007.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]