Abstract

The myriad of co-stimulatory signals expressed, or induced, upon T-cell activation suggests that these signalling pathways shape the character and magnitude of the resulting autoreactive or alloreactive T-cell responses during autoimmunity or transplantation, respectively. Reducing pathological T-cell responses by targeting T-cell co-stimulatory pathways has met with therapeutic success in many instances, but challenges remain. In this Review, we discuss the T-cell co-stimulatory molecules that are known to have critical roles during T-cell activation, expansion, and differentiation. We also outline the functional importance of T cell co-stimulatory molecules in transplantation, tolerance and autoimmunity, and we describe how therapeutic blockade of these pathways might be harnessed to manipulate the immune response to prevent or attenuate pathological immune responses. Ultimately, understanding the interplay between individual co-stimulatory and co-inhibitory pathways engaged during T-cell activation and differentiation will lead to rational and targeted therapeutic interventions to manipulate T-cell responses and improve clinical outcomes.

Introduction

Research over the past decade has resulted in substantial evidence that the ultimate outcome of T-cell tolerance versus immunity is critically regulated by the complement of co-stimulatory and co-inhibitory signals received during T-cell activation. These ‘second signals’ serve to fine-tune the T-cell response, both in terms of its magnitude and the appropriateness of the response, based on the context of antigen presentation. The CD28 (T-cell-specific surface glycoprotein CD28) and CTLA-4 (cytotoxic T-lymphocyte protein 4) pathways were first implicated in tipping the balance between T-cell activation or anergy (whereby the immune system cannot elicit a response), although mounting evidence over the past few years has revealed a number of other co-stimulatory pathways that serve to shape the immunological response further. In this Review, we discuss the critical interactions in the provision of T-cell co-stimulation and the functional importance of these interactions in transplantation, tolerance, and autoimmunity. We also describe how therapeutic blockade of these pathways might be harnessed to manipulate the immune response to prevent or attenuate pathological responses.

The immunoglobulin superfamily [H1]

The CD28, CTLA-4, CD80 and CD86 pathways

Balancing signals: mechanistic insights

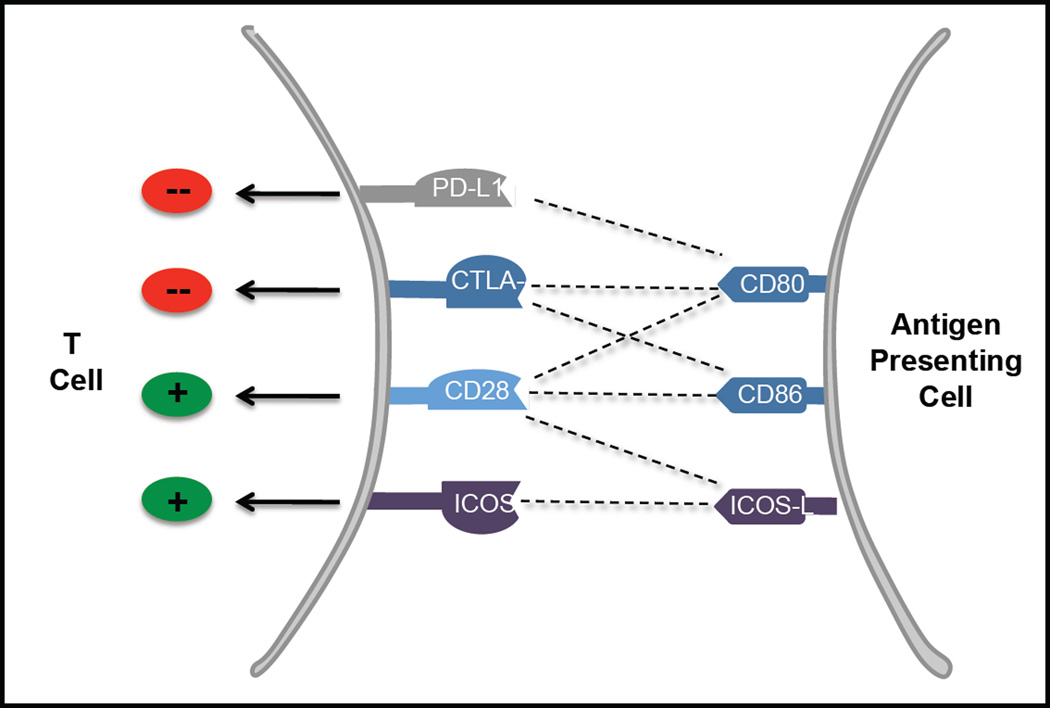

The best studied pathways of the immunoglobulin superfamily are the CD28 and CTLA-4, and the CD80 (T-lymphocyte activation antigen CD80) and CD86 (T-lymphocyte activation antigen CD86) pathways.1,2 CD80 and CD86 are expressed on the surface of antigen presenting cells (APCs) and modulate the activity of responding CD4+ and CD8+ T cells by alternatively binding to the CD28 co-stimulator, which is constitutively expressed on the surface of naive and activated T cells, or the CTLA-4 co-inhibitor, which is inducibly expressed on both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells upon activation (Figure 1). Seminal studies in the early 1990s described the therapeutic blockade of this pathway using an immunoglobulin (Ig) fusion protein, CTLA-4-Ig (abatacept), which binds to CD80 and CD86 and thereby blocks both activating CD28 signals and inhibitory CTLA-4 signals,1,3 in models of transplantation and autoimmunity.3–6 Data from a myriad of studies in the ensuing years revealed further mechanistic insights regarding the effect of CD28 and CTLA-4 blockade on antigen-specific T-cell responses. For example, cell death pathways were shown to be critically involved in T-cell tolerance induced by CD28 and CTLA-4 blockade.7 CD28 and CTLA-4 blockade effectively inhibits naïve antigen-specific CD4+ T-cell responses,8,9 but incompletely controls the expansion of antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell responses.8 In addition, CD8+ memory T-cell responses in both murine and nonhuman primate models are, in most cases, independent of the CD28 pathway during recall immunity10–13 Initial studies using total CD4+ T cells to study CD4+ memory T-cell responses indicated that these cells were effectively attenuated after CTLA-4-Ig administration,10,14 but subsequent in-depth analysis of the effect of co-stimulation blockade on individual CD4+ helper T-cell subsets has suggested a resistance of IL-17 secreting CCR6+ memory type 17 T helper cells (TH17) cells to CD28 and CTLA-4 blockade.15 Furthermore, the initial antigen-specific T-cell precursor frequency was shown to be an important factor in determining the effectiveness of CD28 and CTLA-4 blockade in a murine model of transplantation,16 suggesting that patients with an initially high precursor frequency of autoreactive or alloreactive T cells (as is often the case with poor major histocompatibility complex donor and recipient matching), might be particularly refractory to treatment with CD28 and CTLA-4 blockade.

Figure 1. Complexities of the CD28 co-stimulatory pathway.

The CD28 co-stimulatory receptor can be ligated by CD80, CD86, and ICOS-L (B7-H2). The CTLA-4 co-inhibitor competes with CD28 for binding to CD80 and CD86. However, CD80 can also bind to PD-L1 (B7-H1) and deliver a co-inhibitory signal. ICOS competes with CD28 for binding to B7-H2. Abbreviations: B7-H1, programmed cell death 1 ligand 1; B7-H2, ICOS ligand; CD28, T-cell-specific surface glycoprotein CD28; CD80, T-lymphocyte activation antigen CD80; CD86, T-lymphocyte activation antigen CD86; CTLA-4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte protein 4; ICOS, inducible T-cell costimulator; PD-L1, programmed cell death 1 ligand 1;

Clinical trials for targeting autoimmunity

Given the promising results of CD28 and CTLA-4 blockade in small animal models, strategies to target this pathway were developed in clinical trials for the treatment of autoimmunity. In 2005, CTLA-4-Ig (‘abatacept’) was approved by the FDA for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Clinical trials revealed improvements of RA symptoms in patients treated with abatacept.17,18 Investigators of a seminal study concluded that treatment with abatacept significantly improves symptoms and health-related quality of life in patients with active RA who also receive methotrexate.18 Abatacept is now used as a promising therapy for RA with excellent safety profiles.

A subsequent randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial in type 1 diabetes mellitus revealed co-stimulation modulation with abatacept (measured by residual C-peptide levels) slowed loss of β-cell function over 2 years.19 Interestingly, the beneficial effect of inhibiting T-cell co-stimulation using abatacept observed in this trial has taught us that T cell activation in type 1 diabetes is likely to be continuous over the course of disease progression (at least during the period following clinical diagnosis). However, this study also showed that the decrease in β-cell function with abatacept was no different from placebo after 6 months of treatment, which suggests that the potential clinical benefit of inhibiting T-cell activation with abatacept in type 1 diabetes is limited to the period immediately after diagnosis.19

Abatacept was also evaluated in a clinical trial of allergen-induced airway inflammation. The investigators in this placebo-controlled randomized trial concluded that treatment with abatacept did not alter the inflammatory response to allergen challenge, or improve clinical symptoms in people with mild atopic asthma.20 Similarly, early phase clinical trials of abatacept in patients with multiple sclerosis or ulcerative colitis also showed no efficacy in ameliorating disease symptoms.21–23

Taken together, these results suggest that the T-cell responses elicited by specific autoimmune diseases are differentially susceptible to abatacept. Indeed, abatacept might, in fact, be efficacious in the treatment of type 1 T helper cell (TH1)-mediated autoimmune diseases, such as RA, but less so in the treatment of type 2 T helper cell (TH2), or TH17-mediated autoimmune diseases, such as asthma (TH2-mediated), multiple sclerosis (TH17-mediated), and ulcerative colitis (TH17-mediated).

Preventing transplant rejection

Early preclinical studies using abatacept in nonhuman primate models of renal transplantation demonstrated a failure to adequately prolong graft survival owing to incomplete blockade of CD80 and CD86.24 Further modification of the CTLA-4-Ig protein, aimed to decrease the dissociation rates of this reagent from both CD80 and CD86. These modifications resulted in LEA29Y (‘belatacept’), a second-generation derivative of CTLA-4-Ig that contains two amino acid substitutions. Subsequent research revealed this agent to be 10-fold more potent in vitro, and a more effective inhibitor of renal transplant rejection than abacept24 The promising results from belatacept administration in pre-clinical nonhuman primate studies of renal transplantation led to clinical trials of belatacept for the prophylaxis of renal allograft rejection in the mid-2000s.25 The efficacy of this reagent was tested in an open-label, randomized multi-centre phase III trial that demonstrated superior function of renal transplants, and reduced metabolic and cardiovascular toxicities in the patients treated with belatacept compared to the patients treated with calcineurin inhibitor (CNI). However, patients treated with belatacept experienced a higher incidence and severity of acute rejection episodes 1 year after transplantation than those patients treated with CNI26. The results from studies in murine and nonhuman primate models, and in vitro analyses of human cells, have indicated that this breakthrough rejection is likely to be mediated by CD8+ memory T cells,10,27 or by CD4+ TH17 cells.15,28

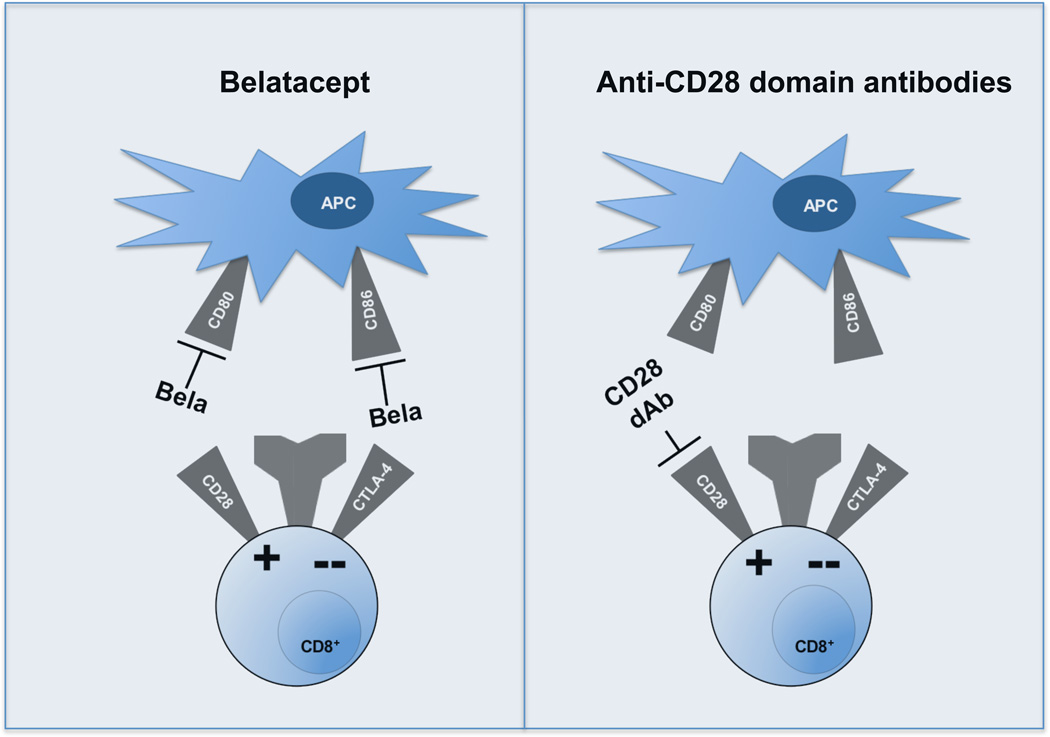

Selectively targeting CD28

Despite the higher incidence of acute rejection episodes in patients who receive belatacept compared with patients who receive CNI therapy, the use of belatacept in CNI-sparing immunosuppressive regimens can [improve both metabolic and cardiovascular profiles—both of which can lead to death in a number of patients— of renal transplant recipients.29 In addition, patients treated with belatacept still exhibit superior kidney function compared with CNI-treated individuals, despite increased incidence of acute rejection. Therefore, the reduced nephrotoxicity afforded by CNI-sparing regimens might outweigh the potential negative impact of acute rejection.29 Long-term follow-up studies of patients treated with belatacept will be important in this regard. However, the immunological effectiveness of the current co-stimulation blockade approaches can clearly be improved and, to this end, the strategy of combined CD28 and CTLA-4 blockade is being re-evaluated. At a mechanistic level, belatacept binds to CD80 and CD86 on APCs and blocks both CD28 and CTLA-4-mediated signals,1,24 inhibiting both co-stimulatory and co-inhibitory signals in responding T cells. Blocking CTLA-4-mediated co-inhibitory signals could detract from the overall goal of attenuating alloreactive T cell responses, in that CTLA-4 signals activate regulatory T (TREG) cells and enhance expression of IDO (Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase), a tryptophan catabolizing pathway implicated in the inhibition of T-cell responses.30–32 Furthermore, CD80 binding to PD-L1 (programmed cell death 1 ligand 1) also inhibits T-cell activation (Figure 1), and this negative regulatory pathway would be blocked by CTLA-4-Ig.33 Thus, at least conceptually, selective blockade of CD28 might alter the balance of co-stimulatory and co-inhibitory molecules engaged during T-cell activation ultimately to improve control of effector differentiation while promoting exhaustion, a process in which T cells gradually lose the ability to divide, make cytokines, and undergo cytolysis, and Treg-mediated suppression (Figure 2). Indeed, selective CD28 blockade was attempted in the phase I trial of the agonistic anti-CD28 monoclonal antibody, TGN1412.34 [The use of TGN1412 in the trial, however, resulted in massive T-cell activation and ‘cytokine storm’—a potentially fatal immunological reaction-- in all six of the patients in this early trial, highlighting the complexities of developing CD28-specific blocking reagents.35,36 Subsequent advances in the production of novel domain antibodies, in which the Fc portion is completely removed, have permitted the development of novel blocking, nonactivating reagents that can safely and specifically block CD28 co-stimulatory signals, while leaving CTLA-4 co-inhibitory signals intact. Along these lines, research in a murine model has shown that the allograft-prolonging effects of selective CD28 blockade with sc28AT, a monovalent CD28-specific fusion antibody, were CTLA-4 dependent,37 providing experimental evidence that blockade of co-inhibitory CTLA-4 signals using CTLA-4-Ig can contribute to incomplete alloreactive T-cell blockade and limit the effectiveness of this drug under some conditions. Translational studies indicated that sc28AT modestly prolongs cardiac and renal allograft survival in a nonhuman primate model (monotherapy, was more effective in combination with CNI than when used as a monotherapy38 and more effectively retains and promotes Foxp3+ TREG cell function. Thus, continued investigation of this pathway might provide the opportunity for further optimization of the therapeutic targeting of the CD28 pathway in transplantation.

Figure 2. Comparison of abatacept and belatacept with selective CD28 blockade, and implications for T-cell activation.

Abatacept and belatacept are both CTLA-4-Ig fusion proteins that bind to both CD80 and CD86 on the surface of APCs, thereby blocking both CD28 co-stimulatory signals as well as CTLA-4 co-inhibitory signals. By contrast, anti-CD28 (dAb) and scFVs each bind selectively to co-stimulatory CD28, inhibiting its binding to CD80 and CD86 while leaving intact the binding of the CTLA-4 co-inhibitor with these ligands. Abbreviations: APCs, antigen presenting cells; CD28, T-cell-specific surface glycoprotein CD28; CD80, T-lymphocyte activation antigen CD80; CD86, T-lymphocyte activation antigen CD86; CTLA-4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte protein 4; dAb, domain antibody; Ig, immunoglobulin; scFV, single-chain variable fragment.

Targeting activated T cells: ICOS and ICOS-L

Another member of the immunoglobulin superfamily of co-stimulatory molecules that has been targeted therapeutically in autoimmunity and transplantation is the inducible T-cell costimulator (ICOS) protein.39 Unlike CD28, ICOS is not expressed on resting CD4+ or CD8+ T cells but is rapidly upregulated upon T-cell activation.40 ICOS is ligated by ICOS ligand (ICOS-L, B7-h2), and can deliver additional co-stimulatory signals to further enhance T-cell activation and differentiation into cytokine-producing effector cells. The expression of ICOS mRNA requires binding of the Jun/Fos heterodimer (AP-1)41 and is regulated by Roquin (probable E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase Roquin), which limits ICOS expression by promoting the degradation of ICOS mRNA.42 A complex relationship exists between the ligands for CD28 and ICOS, in that CD28 can also bind to ICOS-L in humans (albeit with lower affinity than ICOS binds to ICOS-L) (Figure 1).43 The implications of the interaction of these pathways warrant further study.

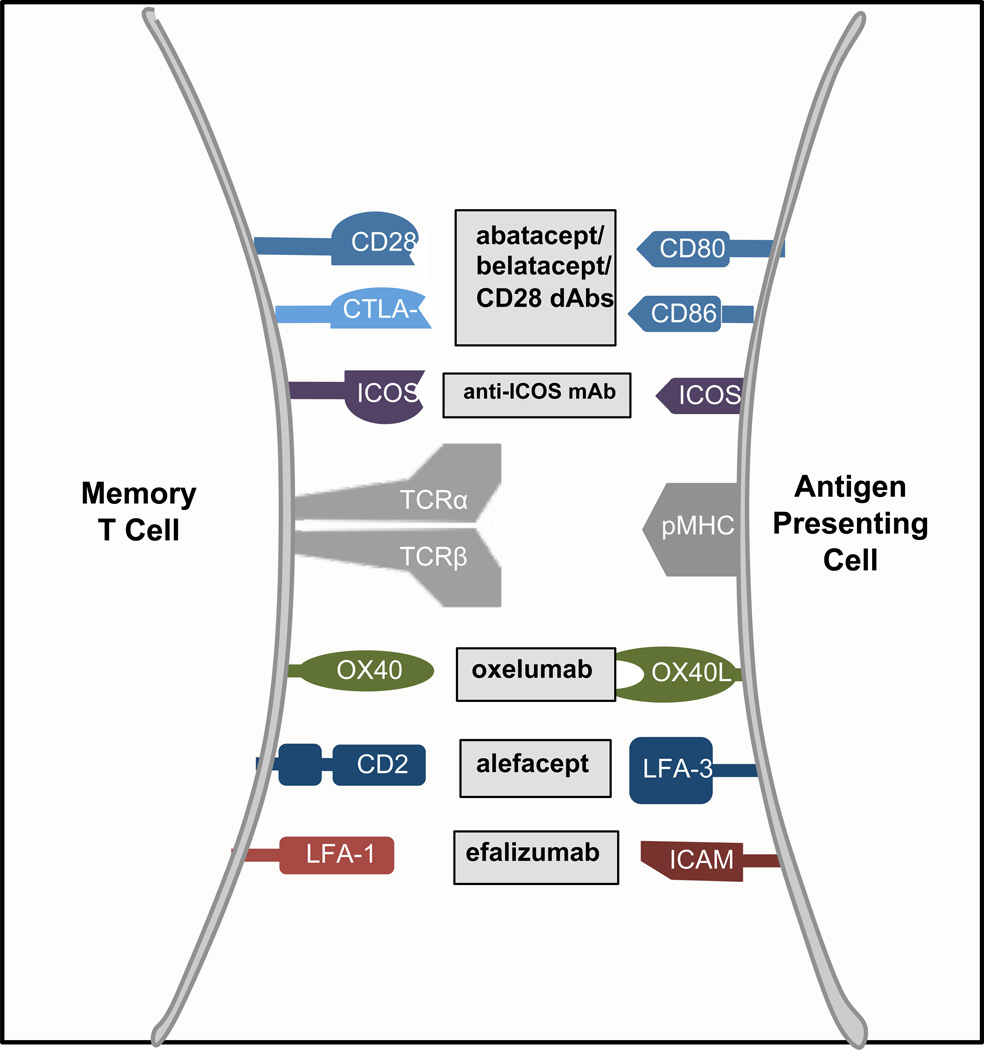

Research using ICOS blockade in models of autoimmunity revealed that co-stimulation through ICOS was actually required for T-cell pathogenesis in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and the development of type 1 diabetes in NOD mice (nonobese diabetic mice—an animal model of type 1 diabetes),44 and that ICOS blockade could be efficacious in inhibiting ongoing activated T-cell responses during autoimmunity.45,46 Likewise, transplant models have revealed that ICOS-mediated signals are crucial for the development of both acute and chronic rejection.47,48 In murine models of transplantation, ICOS antagonism synergized with CTLA-4-Ig to inhibit the effector function of donor-reactive memory T cells and prolong graft survival49 (Figure 3). Inhibition of ICOS interactions with B7h can also ameliorate autoimmune diseases with an antibody-mediated component, such as systemic lupus erythematosus and RA, by interfering with the function of ICOS-expressing follicular helper T cells.50,51 Furthermore, we identified that an important differential effect of selective CD28 blockade compared with CTLA-4-Ig is that selective CD28 blockade results in a profound downregulation of ICOS when compared with untreated or CTLA-4-Ig treated cells, and more effectively inhibits graft rejection in in vivo murine models as compared to CTLA-4 Ig (D. Liu and M. L. Ford, unpublished data). Emerging evidence also suggests that ICOS is critical for the differentiation and co-stimulation of TH17 responses.52–54

Figure 3. Co-stimulatory pathways that might modulate memory T-cell responses in transplantation and autoimmunity.

Some co-stimulatory pathways have been shown to be particularly important for memory T-cell responses in transplantation and autoimmunity. Abatacept and belatacept (both CTLA-4-Ig fusion proteins) and anti-CD28 domain antibodies might target memory T-cell responses by disrupting the CD28 and CTLA-4 pathway. Monoclonal antibodies against ICOS, OX40L (oxelumab), and LFA-1 (efalizumab) target ICOS and ICOS-L, OX40L and OX40, and LFA-1 and ICAM interactions, respectively. Alefacept is LFA-3 Ig fusion protein that competitively inhibits CD2 ligation of LFA-3 on APCs. Abbreviations: APC, antigen presenting cell; CD2, T-cell surface antigen CD2; CD28, T-cell-specific surface glycoprotein CD28; ICAM, Intercellular adhesion molecule 3; CD80, T-lymphocyte activation antigen CD80; CD86, T-lymphocyte activation antigen CD86; ICOS, Inducible T-cell costimulator; CTLA-4, Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte protein 4;LFA-1, Integrin αL (CD11a)/ integrin beta2 (CD18); Ig, immunoglobulin; LFA-3, Lymphocyte function-associated antigen 3; OX40, tumour necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 4; OX40L, tumour necrosis factor ligand superfamily member 4; B7h1, programmed cell death 1 ligand 1; pMHC, peptide/ major histocompatibility complex; TCRα, T-cell receptor alpha chain

Taken together, these findings are clinically relevant in that, as discussed above, pre-existing memory CD8+ T cells and CD4+ TH17 cells might be refractory to the effects of CD28 blockade and mediate breakthrough rejection in recipients treated with CTLA-4-Ig. Thus, these results suggest that adjunct immunomodulatory reagents could attenuate these responses with therapeutic benefit.

TNF family members [H1]

CD154 and CD40 blockade[H2]

Targeting the CD154 (CD40 ligand) and CD40 (Tumour necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 5) pathway is a powerful means of attenuating autoreactive and alloreactive immune responses.55,56 For example, early transplantation and autoimmunity research in NOD mice using an anti-CD154 monoclonal antibody (mAb) revealed a decrease in CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell activation, and in subsequent research, an induction of antigen-specific induced TREG cells.57–59 These results suggest that CD154/CD40 pathway blockade may both inhibit effector T cell responses as well as enhance Treg-mediated immune suppression. Despite these promising preclinical studies, to date, this pathway has not been applied clinically owing to the fact that early clinical trials of Fc-intact CD154 antagonists resulted in unanticipated thromboembolic complications associated with the expression of CD154 on platelets.60

The mechanisms by which CD154 antagonists induce such profound immunomodulation of allospecifc T-cell responses remain controversial. In 2001, Monk and colleagues reported that the tolerogenic effects of anti-CD154 mAb were both Fc-receptor-dependent and complement-dependent because long-term graft survival in Fc-receptor-deficient or complement deficient animals could not be induced.61 However, researchers later suggested that antibody-mediated deletion of CD154-expressing alloreactive cells was not the primary mechanism by which anti-CD154 mAbs induced graft survival. Several reports in both mouse and nonhuman primate models documented the ability of nondepleting anti-CD40 blocking antibodies to exert similar effects to anti-CD154 mAbs.62,63 Daley and colleagues demonstrated that an aglycosylated form of anti-CD154 mAb, which was less able to bind Fc receptors and activate complement, was able to prolong graft survival with a similar efficacy to the wild-type glycosylated form.64 In 2013, we reported on the production and efficacy of a clinically translatable Fc-silent anti-CD154 domain antibody.65 This reagent was generated by fusing a human anti-mouse CD154 Vκ domain antibody to a mutated mouse IgG1 Fc (D265A) to abrogate FcγR interactions and complement activation.66–68 A similar efficacy and ability to attenuate donor-reactive CD8+ T-cell responses, and induce the expansion of a population of graft-specific induced TREG cells compared to traditional Fc-intact anti-CD154 mAb, has been reported.65 Collectively, these results have contributed to a resurgence in the interest in therapeutic targeting of the CD154 and CD40 pathway.

Given the emergence of clinically applicable reagents that block both CD40 and CD154, we now need to better understand the roles of CD154 expressed on dendritic cells and CD40 expressed on CD8+ T cells, and the effect of these pathways on transplant acceptance, or amelioration of autoimmunity. The current dogma is that the CD154 and CD40 pathway contributes to an enhancement of cellular immune responses by virtue of an interaction between CD154 expressed on activated antigen-specific CD4+ T cells and CD40 expressed on dendritic cells.69–71 CD40 signalling into dendritic cells thereby transmits a signal to license the APC, which results in upregulation of CD80, CD86, and other co-stimulatory molecules for the optimal stimulation of CD8+ antigen-specific T-cell responses.72 However, new aspects of CD154 and CD40 biology are unfolding, including a newly appreciated role for CD154 expressed on dendritic cells,73 and studies in models of pathogen infection and autoimmunity suggesting that CD40 might also be expressed on activated T cells.74–76 In a model of transplant rejection, we have also shown that CD40 deficiency on all APCs (donor and host) did not recapitulate the effects of treatment with anti-CD154 mAb, thus indicating a potentially similar effect for alloreactive T cell responses.77 Remarkably, graft survival was prolonged, and the donor-reactive CD8+ T-cell response was attenuated in recipients in which only the donor-reactive CD8+ T cells were deficient in CD40.77 These results suggest that in the setting of transplantation, CD40 functions in a cell-intrinsic manner to augment donor-reactive CD8+ T-cell responses.

On the basis of these advances in our understanding of the biology of CD154 and CD40 pathway blockade, and technological developments in the generation of potentially clinically translatable reagents for targeting this pathway, a number of translational studies with novel CD154 and CD40 antagonists have emerged. Early studies of CD40 blockade employed CD40-depleting reagents that functioned at the level of depleting APCs in vivo.63,78,79 Nondepleting CD40 blockade agents have now been developed that show efficacy in nonhuman primate models of bone marrow, islet, and renal transplantation.80–87 These studies further solidify the notion that pathway blockade, and not antibody-mediated depletion of CD40-expressing cells, underlies the therapeutic effect of these reagents. A phase IIa clinical trial (NCT01780844) of the anti-CD40 monoclonal antibody, ASKP1240, in renal transplantation is currently underway. The results of this trial will be very informative in evaluating the potential of harnessing this pathway to improve clinical outcomes in transplantation, and potentially autoimmunity.

The OX40 and OX40L pathway

The tumour necrosis factor (TNF) receptor family member, OX40, has also been shown to have a key role in the survival and homeostasis of effector and memory T cells in transplantation and autoimmunity. OX40 is not expressed by resting T cells, but is upregulated relatively late after T-cell activation. OX40 is ligated by OX40L when activated T cells bind to APCs.88 Quantitative and qualitative aspects of antigen-specific T-cell responses, including cytokine production, cytolytic function, expansion, and survival, are augmented by OX40-mediated co-stimulatory signals.88 In particular, research indicates that donor-reactive memory T cells, which are resistant to CD28 and CD154 blockade in murine models of transplant rejection, are sensitive to OX40 blockade,89 thus supporting the idea that the OX40 pathway might be a promising therapeutic target for the attenuation of memory T-cell-mediated rejection (Figure 3). An additional interesting aspect of OX40 biology is the accumulating evidence that OX40 signals are critical for controlling the suppressive capacity of Foxp3+ TREG cells. For example, ligation of OX40 on Foxp3+ TREG cells results in a loss of the ability of the Foxp3+ TREG cells to suppress effector T-cell proliferation and IFN-γ production, and precipitates allograft rejection,90 thus implicating OX40 as an important negative regulator of Foxp3+ TREG activity.

However, OX40 is perhaps best appreciated for its critical role in the development of airway inflammation and asthma. OX40−/− mice exhibit reduced lung inflammation and airway hyper-reactivity compared with wild type control mice,91 possibly because of the requirement for OX40 in the development of allergenic TH2 and TH9 responses.92 This work highlights the importance of OX40 in the development of allergic asthma, and indicates that targeting OX40 could prove therapeutically useful. To date, one clinical trial (a phase II study NCT00983658) has been completed using a humanized anti-OX40L mAb (oxelumab) for the prevention of allergen-induced airway inflammation and disease in adults with mild asthma, although the results have not yet been reported. If oxelumab is beneficial to patients with mild asthma, this trial would spur the development of OX40L blockers for other indications in transplantation and autoimmunity. However, clinical trials of abatacept have taught us that distinct autoimmune pathologies might be differentially responsive to inhibition of individual co-stimulatory pathways and that assessment of OX40L blockers in patients with other autoimmune diseases and transplantation is warranted.

Adhesion molecule blockade

Other co-stimulatory pathways, including adhesion molecule pathways, have also been therapeutically targeted in transplantation and autoimmunity. In addition to the ability to deliver co-stimulatory signals into responding T-cell populations, these receptors are intimately involved in the trafficking of activated autoreactive or alloreactive T cells into sites of inflammation.

Preventing trafficking and effector function

The best studied of the adhesion molecule pathways is the LFA-1 (Lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1, a heterodimer of integrin alpha-L (CD11a) and integrin beta-2 (CD18)) pathway. LFA-1 is constitutively expressed on both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells but its expression is increased upon activation and remains high on memory T cells.93 Originally identified as a critically important mediator of T-cell cytolytic function, LFA-1 is now recognized as an important factor in the immunological synapse (the interface between the target cell and the lymphocyte), where it localizes to the centre of the supramolecular activation cluster and stabilizes the transmission of T cell receptor mediated signals.94 In addition, binding of LFA-1 to its ligand ICAM (intercellular adhesion molecule) on inflamed endothelial cells results in the transmigration of activated T cells into sites of inflammation. Interruption of LFA-1 interactions can also blunt natural killer cell responses by inhibiting cytolytic activity. Blockade of these interactions is effective in inhibiting both priming of naive autoreactive and alloreactive T-cell responses, preventing rejection of allogeneic heart grafts, and the development and progression of type 1 diabetes.93 LFA-1 antagonism has also been demonstrated in murine transplant models to inhibit both the trafficking and effector function of donor-reactive memory T cells95, 96 (Figure 3) that are resistant to blockade of both the CD28, and CD154 and CD40 pathways. For this reason, LFA-1 antagonism is a clinically attractive, especially for use in highly sensitized individuals, such as patients undergoing a repeat transplant, or those individuals with high numbers of memory T cells owing to a persistent inflammatory state associated with chronic kidney disease, or underlying autoimmunity.

Translational research in nonhuman primate models has confirmed the hypothesis that LFA-1 antagonism can effectively inhibit donor-reactive memory T-cell populations, and thereby confer a therapeutic advantage.97–99 In a rhesus macaque model of alloislet transplantation, LFA-1 antagonism synergized with belatacept, and prolonged graft survival.99 Associated in vitro analyses confirmed an inhibitory effect on the CD8+ memory T-cell compartment.99 In most studies, LFA-1 antagonism is not ‘tolerance-inducing’, meaning that weaning patients off the drug invariably leads to allograft rejection. However, the combination of LFA-1 antagonism in the presence of sirolimus (also known as rapamycin) can lead to prolonged graft survival even after cessation of all immunosuppression.99 This observed long-term graft survival could have been the result of an increased frequency or functionality of Foxp3+ TREG cells, as both LFA-1 antagonism and sirolimus have been shown to have pro-TREG effects, by increasing the ratio of TREG to effector T cells in secondary lymphoid organs, and enhancing the survival of TREG, respectively,100,101 although more work is needed to confirm this hypothesis.

The LFA-1 antagonist, efalizumab, was successfully translated into the clinic, first for the treatment of plaque psoriasis,102,103 where it was used successfully for a number of years. Efalizumab has also been studied in pilot clinical trials of renal and islet transplantation (NCT00737763, NCT00672204, NCT00729768).104–106 These trials revealed promising results in terms of preventing graft rejection. In the two islet transplant trials, 100% of the patients treated with efalizumab maintained insulin independence for the duration of treatment. Interestingly, investigators in one study also noted a striking TREG signature in patients treated with efalizumab in combination with sirolimus—the number of TREG cells in peripheral blood was dramatically increased in all six patients monitored, relative to TREG levels before the transplant,105 again suggesting a very interesting biology with regard to the effect of LFA-1 antagonism on TREG cells. These results support the hypothesis that LFA-1 antagonists might be effectively paired with sirolimus in order to enhance T-cell regulation and inhibit rejection. Unfortunately, further development of efalizumab in transplantation, and its clinical use for psoriasis, was halted when the drug was withdrawn from the market after three of ~40,000 treated patients (0.008%) presented with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy—a rare but potentially fatal John Cunningham polyomavirus-associated disease.107,108 While the future of clinical development of LFA-1 antagonists remains uncertain, the large number of patients treated with LFA-1 antagonists combined with a side effect profile not dissimilar to those immunosuppressants already in clinical practice suggests that, for transplantation in particular, blockade of the LFA-1 pathway could be an efficacious and safe method of attenuating transplant rejection, while avoiding the nephrotoxicity and other adverse effects associated with current CNI-based immunosuppressive regimens. In order to assess LFA-1 pathway blockade and its potential utility for the attenuation of pathological immune responses, we must increase our understanding of the mechanisms of action of LFA-1 blockade, particularly with regard to effects on TREG cells and donor-reactive memory T cells.

Targeting CD2 and LFA-3 interactions [H2]

Co-stimulatory and adhesion molecule blockade strategies have also targeted CD2 (T-cell surface antigen CD2) and LFA-3 (lymphocyte function-associated antigen 3) interactions. Like LFA-1, CD2 is constitutively expressed on both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells but is increased upon activation,109 and is more highly expressed on effector memory T-cells than central memory T-cells110 Effector memory cells are those that constantly traffic through peripheral tissues and are poised to rapidly exert effector function upon encounter with cognate antigen, and thus may represent the first wave of effector cells during an immune attack on a transplanted organ. Also, like LFA-1, ligation of the receptor has multiple effects including direct transmission of co-stimulatory signals as well as facilitating T cell to APC adhesion.111,112 In vitro mechanistic research revealed that inhibition of CD2 and LFA-3 interactions using an LFA-3 fusion protein (alefacept) preferentially targeted CD2hi memory T cells (Figure 3) and inhibited the proliferation of belatacept-resistant CD8+ memory T cells.113 Alefacept has been successfully used clinically to treat plaque psoriasis mediated by effector memory T cells,114,115 and the results from translational studies in nonhuman primate models of renal transplantation indicate that alefacept synergizes with belatacept and anti-CD154 mAb in prolonging allograft survival.110 However, subsequent research in anti-CD154-sparing models of both renal and islet allotransplantation revealed no additional beneficial effect of alefacept over belatacept and sirolimus alone. In fact, the addition of alefacept was associated with an increase in the incidence of cytomegalovirus reactivation and afforded no benefit in terms of graft survival.116,117 Clearly, a improved understanding of CD2 biology in transplantation and autoimmunity is needed, and further preclinical mechanistic studies are required in order to ascertain the utility of CD2 blockers in the antirejection armamentarium.

Synergistic effects

A number of studies, many of which have been mentioned above, have provided evidence that simultaneous blockade of multiple co-stimulatory pathways leads to more efficacious inhibition of autoreactive and alloreactive T-cell responses, and better outcomes in experimental models of autoimmunity and transplantation than inhibition of any one pathway alone. In particular, research in murine models of both transplantation (skin and heart)6 and autoimmunity (type 1 diabetes),118 and nonhuman primate models of transplantation (renal and islet),83,119,120 has revealed that combined blockade of the CD28, and CD154 and CD40 pathways results in superior outcomes relative to blockade of either pathway in isolation. The FDA approval of belatacept has thus spurred interest in developing a clinically translatable strategy to inhibit the CD154 and CD40 pathway in order to harness this synergy to achieve maximum benefit in clinical application. At a mechanistic level, work from our group now indicates that, whereas classical natural TREG cells are reduced after treatment with CTLA-4-Ig, frequencies of CD154 blockade-induced antigen-specific induced TREG cells are actually enhanced in the presence of CTLA-4-Ig.65 This work provides at least one mechanism by which blockade of these two pathways synergizes in inhibiting T cell activation and effector function.

Synergistic increases in efficacy are also observed after blockade of additional co-stimulatory pathways. Blockade of CD28 and ICOS pathways synergize in preventing effector function of donor-reactive memory T cells.49 Blockade of OX40 signalling synergizes with blockade of the CD28 and CD154 pathways in preventing T-cell activation and prolonging graft survival.121 LFA-1 antagonism has also been shown to synergize with both CD2899 and CD154 blockade alone,122,123 and combined CD154 and CD28 blockade96,124 to inhibit memory T-cell activation in models of type 1 diabetes and transplantation. The observed synergistic effects of blocking multiple co-stimulatory pathways is likely to be indicative of the redundancy that exists within T-cell co-stimulatory mechanisms, in that, blockade of multiple pathways with overlapping effects will be required in order to maximize efficacy and improve outcomes clinically.

Future research

While each of the co-stimulation pathways described in this Review attenuates autoreactive and alloreactive T-cell responses by blocking the signals required for optimal activation and differentiation, most have shown efficacy only under conditions in which the drug is administered continuously, with the re-emergence of pathological immune responses (such as autoimmunity or graft rejection) with cessation of treatment. However, the original hypothesis held that co-stimulatory signal blockade invoked during the initial antigen encounter would enable the deletion, or induction, of a permanent state of anergy selectively in antigen-specific T cells. Under these conditions, the remainder of the T-cell repertoire would be left fully functional, thereby maintaining immune competence against microbial antigens.125 However, the emergence of new thymic emigrants months after cessation of therapy would potentially break this tolerant state and result in graft rejection, or the return of autoimmunity. With these issues in mind, several groups have attempted haematopoietic stem cell transplantation under the cover of co-stimulation blockade with the idea that durable mixed chimerism would facilitate the continuous negative selection of alloreactive T cells in the thymus and, thus, allow a permanent state of tolerance via this central tolerance based mechanism.126–128 This therapeutic strategy continues to be actively investigated, although whether the induction of haematopoietic chimerism is either necessary, or sufficient, for the establishment of the tolerant state remains controversial.

In the absence of haematopoietic stem cell transplantation, and the establishment of mixed chimerism, blockade of the majority of the pathways discussed above has resulted in prolonged graft survival but failed to induce tolerance. One notable exception is the CD154 and CD40 pathway—blockade of which, has been shown in some mouse models to induce long-term allograft survival after cessation of treatment.129–133 Data from numerous studies show that blockade of the CD154 and CD40 pathway is associated with an expansion of Foxp3+ TREG cells that traffic to the graft,57,58,134–136 and that Foxp3+ TREG cells are required for the establishment and maintenance of tolerance.135 In addition, CD154 and CD40 induced tolerance can be transferred to a naive recipient who has never received CD154 or CD40 blockade by adoptively transferring CD4+ Foxp3+ T cells.136 Interestingly, evidence now suggests that, whereas inflammatory cytokines elicited after pathogen infection can break this tolerance, once infection is cleared and the host can accept a repeat graft from the same donor, tolerance is spontaneously re-established.132,133 Blockade of the CD154 and CD40 pathway, in particular, has the potential to induce tolerance through peripherally-induced TREG cell based mechanisms in immunologically naive mice. However, tolerance after CD154 and CD40 blockade is not induced in all models, including models of skin transplantation in naive animals,58 transplantation into immunologically experienced hosts,137 and, importantly, in nonhuman primate models of kidney and islet transplantation.83,84 Improved understanding of the mechanisms underlying the immunological nonresponsiveness observed after blockade of this pathway is required for translational research in large animal models and, ultimately, clinical application.

Conclusions [H1]

From the panoply of co-stimulatory signals expressed, either constitutively or upon activation, co-stimulatory molecules clearly have the potential to critically effect, and shape, the magnitude and character of resulting autoreactive or alloreactive T-cell responses. Whereas this Review focuses on the well-investigated co-stimulatory pathways, much less is known about many other pathways (such as the 4-1BB [tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 9] and 4-1BBL[tumor necrosis factor ligand superfamily member 9] pathway, and the CD27 [CD27 antigen] and CD70 [CD70 antigen] pathway) that are likely to also have important and context-dependent roles in orchestrating the generation of pathological T-cell responses in transplantation and autoimmunity. Furthermore, an equally complex complement of co-inhibitory receptors (including PD-1 [programmed cell death protein 1], BTLA [B- and T-lymphocyte attenuator], and LAG-3 [lymphocyte activation gene 3 protein] can function to further fine-tune responding T-cell populations. Ultimately, understanding the interplay between individual co-stimulatory and co-inhibitory pathways engaged during T-cell activation and differentiation might lead to rational and targeted therapeutic interventions in order to attenuate unwanted T-cell responses and improve outcomes in autoimmunity and transplantation.

Key Points.

T-cell co-stimulatory signals, expressed either constitutively or upon activation, critically affect the magnitude and character of autoreactive or alloreactive T-cell responses

Targeting T-cell co-stimulation pathways to reduce pathological T-cell responses has met with therapeutic success in many instances, but challenges remain

Efficacy of co-stimulatory blockade with abatacept or belatacept could be further optimized to improve inhibition of alloreactive and autoreactive T-cell responses by leaving co-inhibitory signals intact

Clinical application of CD154 pathway blockade has, thus far, been limited, but novel reagents in development might allow for therapeutic manipulation of this pathway to achieve immunological tolerance

Several other T-cell co-stimulatory pathways also hold promise as therapeutic targets for the treatment of autoimmunity and transplant rejection

Understanding the interplay between individual co-stimulatory and co-inhibitory pathways will lead to rational and targeted therapeutic interventions to manipulate T-cell responses and improve clinical outcomes

Review criteria.

The articles on which this review is based were selected by searching the PubMed database; all years covered in the database were included. Search terms used were the following: CTLA-4 Ig autoimmunity, CTLA-4 Ig transplantation, CD154 autoimmunity, CD154 transplantation, ICOS autoimmunity, ICOS transplantation, OX40L autoimmunity, OX40L transplantation, LFA-1 autoimmunity, LFA-1 transplantation, alefacept autoimmunity, alefacept transplantation. To identify clinical trials the “clinical trial” filter in PubMed was used. References selected for further perusal were in English and were full-length articles and not abstracts. After selecting and reading individual papers identified by these search terms, additional manuscripts referenced within these works were reviewed and some of those manuscripts are referred to in this article as well.

Acknowledgements

MLF is supported by R01 AI073707 and R01 AI104699. ABA and TCP are supported by U19 AI1051731.. The authors acknowledge Scott M. Krummey, Emory University for help with conceptualization and design of figures.

Footnotes

Competing interests

M. L. Ford and A. B. Adams declare an association with the following company: Bristol-Myers Squibb. T. C. Pearson declares an association with the following companies: Bristol-Myers Squibb and Astellas. See the article online for full details of the relationships.

Author contributions

M. L. Ford researched the data for the article. T. C. Pearson and M. L. Ford provided substantial contribution to discussions of the content. T. C. Pearson and M. L. Ford contributed to writing the article. T. C. Pearson, M. L. Ford and A. B. Adams contributed substantially to review and/or editing of the manuscript before submission.

References

- 1.Salomon B, Bluestone JA. Complexities of CD28/B7: CTLA-4 costimulatory pathways in autoimmunity and transplantation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:225–252. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bour-Jordan H, et al. Intrinsic and extrinsic control of peripheral T-cell tolerance by costimulatory molecules of the CD28/ B7 family. Immunol Rev. 2011;241:180–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01011.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Linsley PS, et al. Immunosuppression in vivo by a soluble form of the CTLA-4 T cell activation molecule. Science. 1992;257:792–795. doi: 10.1126/science.1496399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lenschow D, et al. Long-term survival of xenogeneic pancreatic islet grafts induced by CTLA4Ig. Science. 1992;257:789–792. doi: 10.1126/science.1323143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Finck BK, Linsley PS, Wofsy D. Treatment of murine lupus with CTLA4Ig. Science. 1994;265:1225–1227. doi: 10.1126/science.7520604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larsen CP, et al. Long-term acceptance of skin and cardiac allografts after blocking CD40 and CD28 pathways. Nature. 1996;381:434–438. doi: 10.1038/381434a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wells AD, et al. Requirement for T-cell apoptosis in the induction of peripheral transplantation tolerance. Nature Medicine. 1999;5:1303–1307. doi: 10.1038/15260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trambley J, et al. Asialo GM1(+) CD8(+) T cells play a critical role in costimulation blockade-resistant allograft rejection. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:1715–1722. doi: 10.1172/JCI8082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ford ML, et al. A critical precursor frequency of donor-reactive CD4+ T cell help is required for CD8+ T cell-mediated CD28/CD154-independent rejection. J Immunol. 2008;180:7203–7211. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adams AB, et al. Heterologous immunity provides a potent barrier to transplantation tolerance. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1887–1895. doi: 10.1172/JCI17477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Floyd TL, et al. Limiting the amount and duration of antigen exposure during priming increases memory T cell requirement for costimulation during recall. J Immunol. 2011;186:2033–2041. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bingaman AW, Farber DL. Memory T cells in transplantation: generation, function, and potential role in rejection. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:846–852. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamada Y, et al. Overcoming memory T-cell responses for induction of delayed tolerance in nonhuman primates. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:330–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03795.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ndejembi MP, et al. Control of memory CD4 T cell recall by the CD28/B7 costimulatory pathway. J Immunol. 2006;177:7698–7706. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.11.7698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yuan X, et al. A novel role of CD4 Th17 cells in mediating cardiac allograft rejection and vasculopathy. J Exp Med. 2008;205:3133–3144. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ford ML, et al. Antigen-specific precursor frequency impacts T cell proliferation, differentiation, and requirement for costimulation. J Exp Med. 2007;204:299–309. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Genovese MC, et al. Abatacept for rheumatoid arthritis refractory to tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibition. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1114–1123. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kremer JM, et al. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis by selective inhibition of T-cell activation with fusion protein CTLA4Ig. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1907–1915. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Orban T, et al. Co-stimulation modulation with abatacept in patients with recent-onset type 1 diabetes: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;378:412–419. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60886-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parulekar AD, et al. A randomized controlled trial to evaluate inhibition of T-cell costimulation in allergen-induced airway inflammation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:494–501. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201207-1205OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linsley PS, Nadler SG. The clinical utility of inhibiting CD28-mediated costimulation. Immunol Rev. 2009;229:307–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Merrill JT, et al. The efficacy and safety of abatacept in patients with non-life-threatening manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus: results of a twelve-month, multicenter, exploratory, phase IIb, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:3077–3087. doi: 10.1002/art.27601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sandborn WJ, et al. Abatacept for Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:62–69. e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Larsen CP, et al. Rational development of LEA29Y (belatacept), a high-affinity variant of CTLA4-Ig with potent immunosuppressive properties. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:443–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vincenti F, et al. Costimulation blockade with belatacept in renal transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:770–781. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vincenti F, et al. A Phase III Study of Belatacept-based Immunosuppression Regimens versus Cyclosporine in Renal Transplant Recipients (BENEFIT Study) Am J Transplant. 2010;10:535–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.03005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nadazdin O, et al. Host alloreactive memory T cells influence tolerance to kidney allografts in nonhuman primates. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:86ra51. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burrell BE, Csencsits K, Lu G, Grabauskiene S, Bishop DK. CD8+ Th17 mediate costimulation blockade-resistant allograft rejection in T-bet-deficient mice. J Immunol. 2008;181:3906–3914. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.3906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vincenti F, et al. Five-year safety and efficacy of belatacept in renal transplantation. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2010;21:1587–1596. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009111109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mellor AL, et al. Specific subsets of murine dendritic cells acquire potent T cell regulatory functions following CTLA4-mediated induction of indoleamine 2,3 dioxygenase. Int Immunol. 2004;16:1391–1401. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mellor AL, Munn DH. IDO expression by dendritic cells: tolerance and tryptophan catabolism. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:762–774. doi: 10.1038/nri1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Munn DH, Sharma MD, Mellor AL. Ligation of B7-1/B7-2 by human CD4+ T cells triggers indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase activity in dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2004;172:4100–4110. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.7.4100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Butte MJ, Keir ME, Phamduy TB, Sharpe AH, Freeman GJ. Programmed death-1 ligand 1 interacts specifically with the B7-1 costimulatory molecule to inhibit T cell responses. Immunity. 2007;27:111–122. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suntharalingam G, et al. Cytokine storm in a phase 1 trial of the anti-CD28 monoclonal antibody TGN1412. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1018–1028. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Waibler Z, et al. Toward experimental assessment of receptor occupancy: TGN1412 revisited. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:890–892. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Waibler Z, et al. Signaling signatures and functional properties of anti-human CD28 superagonistic antibodies. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1708. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang T, et al. Selective CD28 blockade attenuates acute and chronic rejection of murine cardiac allografts in a CTLA-4-dependent manner. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:1599–1609. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03624.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Poirier N, et al. Inducing CTLA-4-dependent immune regulation by selective CD28 blockade promotes regulatory T cells in organ transplantation. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:17ra10. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hutloff A, et al. ICOS is an inducible T-cell co-stimulator structurally and functionally related to CD28. Nature. 1999;397:263–266. doi: 10.1038/16717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dong C, et al. ICOS co-stimulatory receptor is essential for T-cell activation and function. Nature. 2001;409:97–101. doi: 10.1038/35051100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Watanabe M, et al. AP-1 is involved in ICOS gene expression downstream of TCR/CD28 and cytokine receptor signaling. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42:1850–1862. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yu D, et al. Roquin represses autoimmunity by limiting inducible T-cell co-stimulator messenger RNA. Nature. 2007;450:299–303. doi: 10.1038/nature06253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yao S, et al. B7-h2 is a costimulatory ligand for CD28 in human. Immunity. 2010;34:729–740. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ansari MJ, et al. Role of ICOS pathway in autoimmune and alloimmune responses in NOD mice. Clin Immunol. 2008;126:140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2007.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sporici RA, et al. ICOS ligand costimulation is required for T-cell encephalitogenicity. Clin Immunol. 2001;100:277–288. doi: 10.1006/clim.2001.5074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sporici RA, Perrin PJ. Costimulation of memory T-cells by ICOS: a potential therapeutic target for autoimmunity? Clin Immunol. 2001;100:263–269. doi: 10.1006/clim.2001.5093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ozkaynak E, et al. Importance of ICOS-B7RP-1 costimulation in acute and chronic allograft rejection. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:591–596. doi: 10.1038/89731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nanji SA, et al. Costimulation blockade of both inducible costimulator and CD40 ligand induces dominant tolerance to islet allografts and prevents spontaneous autoimmune diabetes in the NOD mouse. Diabetes. 2006;55:27–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schenk AD, Gorbacheva V, Rabant M, Fairchild RL, Valujskikh A. Effector functions of donor-reactive CD8 memory T cells are dependent on ICOS induced during division in cardiac grafts. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:64–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02460.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hu YL, Metz DP, Chung J, Siu G, Zhang M. B7RP-1 blockade ameliorates autoimmunity through regulation of follicular helper T cells. J Immunol. 2009;182:1421–1428. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.3.1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nurieva RI, Treuting P, Duong J, Flavell RA, Dong C. Inducible costimulator is essential for collagen-induced arthritis. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:701–706. doi: 10.1172/JCI17321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 52.Park H, et al. A distinct lineage of CD4 T cells regulates tissue inflammation by producing interleukin 17. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1133–1141. doi: 10.1038/ni1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Paulos CM, et al. The inducible costimulator (ICOS) is critical for the development of human T(H)17 cells. Science translational medicine. 2010;2:55ra78. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Garaude J, Blander JM. ICOStomizing immunotherapies with T(H)17. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:55ps52. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kirk AD, et al. Treatment with humanized monoclonal antibody against CD154 prevents acute renal allograft rejection in nonhuman primates. Nat Med. 1999;5:686–693. doi: 10.1038/9536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Larsen CP, et al. Long-term acceptance of skin and cardiac allografts after blocking CD40 and CD28 pathways. Nature. 1996;381:434–438. doi: 10.1038/381434a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ochando JC, et al. Alloantigen-presenting plasmacytoid dendritic cells mediate tolerance to vascularized grafts. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:652–662. doi: 10.1038/ni1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ferrer IR, et al. Antigen-specific induced Foxp3+ regulatory T cells are generated following CD40/CD154 blockade. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:20701–20706. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105500108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kendal AR, et al. Sustained suppression by Foxp3+ regulatory T cells is vital for infectious transplantation tolerance. J Exp Med. 208:2043–2053. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kawai T, Andrews D, Colvin RB, Sachs DH, Cosimi AB. Thromboembolic complications after treatment with monoclonal antibody against CD40 ligand. Nat Med. 2000;6:114. doi: 10.1038/72162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Monk NJ, et al. Fc-dependent depletion of activated T cells occurs through CD40L-specific antibody rather than costimulation blockade. Nat Med. 2003;9:1275–1280. doi: 10.1038/nm931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gilson CR, et al. Anti-CD40 monoclonal antibody synergizes with CTLA4-Ig in promoting long-term graft survival in murine models of transplantation. J Immunol. 2009;183:1625–1635. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Haanstra KG, et al. Prevention of kidney allograft rejection using anti-CD40 and anti-CD86 in primates. Transplantation. 2003;75:637–643. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000054835.58014.C2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Daley SR, Cobbold SP, Waldmann H. Fc-disabled anti-mouse CD40L antibodies retain efficacy in promoting transplantation tolerance. Am J Transplant. 2008;8:2265–2271. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pinelli DF, et al. An Anti-CD154 Domain Antibody Prolongs Graft Survival and Induces FoxP3+ iTreg in the Absence and Presence of CTLA-4 Ig. Am J Transplant. 2013 doi: 10.1111/ajt.12417. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Clynes RA, Towers TL, Presta LG, Ravetch JV. Inhibitory Fc receptors modulate in vivo cytotoxicity against tumor targets. Nat Med. 2000;6:443–446. doi: 10.1038/74704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nimmerjahn F, Bruhns P, Horiuchi K, Ravetch JV. FcgammaRIV: a novel FcR with distinct IgG subclass specificity. Immunity. 2005;23:41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Baudino L, et al. Crucial role of aspartic acid at position 265 in the CH2 domain for murine IgG2a and IgG2b Fc-associated effector functions. J Immunol. 2008;181:6664–6669. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.6664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bennett SRM, et al. Help for cytotoxic-T-cell responses is mediated by CD40 signalling. Nature. 1998;393:478–480. doi: 10.1038/30996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ridge JP, Di Rosa F, Matzinger P. A conditioned dendritic cell can be a temporal bridge between CD4+ T-helper and a T-killer cell. Nature. 1998;393:474–478. doi: 10.1038/30989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schoenberger SP, Toes RE, van der Voort EI, Offringa R, Melief CJ. T-cell help for cytotoxic T lymphocytes is mediated by CD40-CD40L interactions. Nature. 1998;393:480–483. doi: 10.1038/31002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Elgueta R, et al. Molecular mechanism and function of CD40/CD40L engagement in the immune system. Immunol Rev. 2009;229:152–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00782.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Johnson S, et al. Selected Toll-like receptor ligands and viruses promote helper-independent cytotoxic T cell priming by upregulating CD40L on dendritic cells. Immunity. 2009;30:218–227. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bourgeois C, Rocha B, Tanchot C. A role for CD40 expression on CD8+ T cells in the generation of CD8+ T cell memory. Science. 2002;297:2060–2063. doi: 10.1126/science.1072615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Munroe ME. Functional roles for T cell CD40 in infection and autoimmune disease: the role of CD40 in lymphocyte homeostasis. Semin Immunol. 2009;21:283–288. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bhadra R, Gigley JP, Khan IA. Cutting edge: CD40-CD40 ligand pathway plays a critical CD8-intrinsic and -extrinsic role during rescue of exhausted CD8 T cells. J Immunol. 2011;187:4421–4425. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liu D, Ferrer IR, Konomos M, Ford ML. Inhibition of CD8+ T Cell–Derived CD40 Signals Is Necessary but Not Sufficient for Foxp3+ Induced Regulatory T Cell Generation In Vivo. J Immunol. 2013 doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300267. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pearson TC, et al. Anti-CD40 therapy extends renal allograft survival in rhesus macaques. Transplantation. 2002;74:933–940. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200210150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Adams AB, et al. Development of a chimeric anti-CD40 monoclonal antibody that synergizes with LEA29Y to prolong islet allograft survival. J Immunol. 2005;174:542–550. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.1.542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Thompson P, et al. CD40-specific costimulation blockade enhances neonatal porcine islet survival in nonhuman primates. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:947–957. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03509.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Badell IR, et al. CTLA4Ig prevents alloantibody formation following nonhuman primate islet transplantation using the CD40-specific antibody 3A8. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:1918–1923. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04029.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Page A, et al. CD40 blockade combines with CTLA4Ig and sirolimus to produce mixed chimerism in an MHC-defined rhesus macaque transplant model. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:115–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03737.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lowe M, et al. A novel monoclonal antibody to CD40 prolongs islet allograft survival. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:2079–2087. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04054.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Badell IR, et al. Nondepleting anti-CD40-based therapy prolongs allograft survival in nonhuman primates. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:126–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03736.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Oura T, et al. Long-term hepatic allograft acceptance based on CD40 blockade by ASKP1240 in nonhuman primates. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:1740–1754. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Aoyagi T, et al. A human anti-CD40 monoclonal antibody, 4D11, for kidney transplantation in cynomolgus monkeys: induction and maintenance therapy. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:1732–1741. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Imai A, et al. A novel fully human anti-CD40 monoclonal antibody, 4D11, for kidney transplantation in cynomolgus monkeys. Transplantation. 2007;84:1020–1028. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000286058.79448.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Croft M. The role of TNF superfamily members in T-cell function and diseases. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:271–285. doi: 10.1038/nri2526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Vu MD, et al. Critical, but Conditional, Role of OX40 in Memory T Cell-Mediated Rejection. J Immunol. 2006;176:1394–1401. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.3.1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Vu MD, et al. OX40 costimulation turns off Foxp3+ Tregs. Blood. 2007;110:2501–2510. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-070748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Jember AG, Zuberi R, Liu FT, Croft M. Development of allergic inflammation in a murine model of asthma is dependent on the costimulatory receptor OX40. J Exp Med. 2001;193:387–392. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.3.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Xiao X, et al. OX40 signaling favors the induction of T(H)9 cells and airway inflammation. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:981–990. doi: 10.1038/ni.2390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Nicolls MR, Gill RG. LFA-1 (CD11a) as a therapeutic target. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:27–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Springer TA, Dustin ML. Integrin inside-out signaling and the immunological synapse. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2012;24:107–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Setoguchi K, et al. LFA-1 Antagonism Inhibits Early Infiltration of Endogenous Memory CD8 T Cells into Cardiac Allografts and Donor-Reactive T Cell Priming. Am J Transplant. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03492.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kitchens WH, et al. Integrin Antagonists Prevent Costimulatory Blockade-Resistant Transplant Rejection by CD8(+) Memory T Cells. Am J Transplant. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03762.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Thompson P, et al. Alternative immunomodulatory strategies for xenotransplantation: CD40/154 pathway-sparing regimens promote xenograft survival. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:1765–1775. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04031.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Poston RS, et al. Effects of humanized monoclonal antibody to rhesus CD11a in rhesus monkey cardiac allograft recipients. Transplantation. 2000;69:2005–2013. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200005270-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Badell IR, et al. LFA-1-specific therapy prolongs allograft survival in rhesus macaques. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:4520–4531. doi: 10.1172/JCI43895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Reisman NM, et al. LFA-1 blockade induces effector and regulatory T-cell enrichment in lymph nodes and synergizes with CTLA-4Ig to inhibit effector function. Blood. 2011;118:5851–5861. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-347252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Singh K, et al. Regulatory T cells exhibit decreased proliferation but enhanced suppression after pulsing with sirolimus. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:1441–1457. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03963.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lebwohl M, et al. A novel targeted T-cell modulator, efalizumab, for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2004–2013. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Leonardi CL, et al. Extended efalizumab therapy improves chronic plaque psoriasis: results from a randomized phase III trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:425–433. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Vincenti F, et al. A phase I/II randomized open-label multicenter trial of efalizumab, a humanized anti-CD11a, anti-LFA-1 in renal transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:1770–1777. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Posselt AM, et al. Islet transplantation in type 1 diabetics using an immunosuppressive protocol based on the anti-LFA-1 antibody efalizumab. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:1870–1880. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03073.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Turgeon NA, et al. Experience with a Novel Efalizumab-Based Immunosuppressive Regimen to Facilitate Single Donor Islet Cell Transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03212.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Carson KR, et al. Monoclonal antibody-associated progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy in patients treated with rituximab, natalizumab, and efalizumab: a Review from the Research on Adverse Drug Events and Reports (RADAR) Project. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:816–824. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70161-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Tan CS, Koralnik IJ. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy and other disorders caused by JC virus: clinical features and pathogenesis. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:425–437. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70040-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Sanders ME, et al. Human memory T lymphocytes express increased levels of three cell adhesion molecules (LFA-3, CD2, and LFA-1) and three other molecules (UCHL1, CDw29, and Pgp-1) and have enhanced IFN-gamma production. J Immunol. 1988;140:1401–1407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Weaver TA, et al. Alefacept promotes co-stimulation blockade based allograft survival in nonhuman primates. Nat Med. 2009;15:746–749. doi: 10.1038/nm.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Moingeon P, et al. CD2-mediated adhesion facilitates T lymphocyte antigen recognition function. Nature. 1989;339:312–314. doi: 10.1038/339312a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.van der Merwe PA. A subtle role for CD2 in T cell antigen recognition. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1371–1374. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.10.1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Lo DJ, et al. Selective targeting of human alloresponsive CD8+ effector memory T cells based on CD2 expression. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:22–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03317.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ellis CN, Krueger GG Alefacept Clinical Study, G. Treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis by selective targeting of memory effector T lymphocytes. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:248–255. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107263450403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Brimhall AK, King LN, Licciardone JC, Jacobe H, Menter A. Safety and efficacy of alefacept, efalizumab, etanercept and infliximab in treating moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:274–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Lowe MC, et al. Belatacept and sirolimus prolong nonhuman primate islet allograft survival: adverse consequences of concomitant alefacept therapy. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:312–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04341.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Lo DJ, et al. Belatacept and sirolimus prolong nonhuman primate renal allograft survival without a requirement for memory T cell depletion. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:320–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04342.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Rigby MR, Trexler AM, Pearson TC, Larsen CP. CD28/CD154 blockade prevents autoimmune diabetes by inducing nondeletional tolerance after effector t-cell inhibition and regulatory T-cell expansion. Diabetes. 2008;57:2672–2683. doi: 10.2337/db07-1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Kirk AD, et al. CTLA4Ig and anti-CD40 ligand prevent renal allograft rejection in primates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:8789–8794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Badell IR, et al. Nondepleting Anti-CD40-Based Therapy Prolongs Allograft Survival in Nonhuman Primates. Am J Transplant. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03736.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Demirci G, et al. Critical role of OX40 in CD28 and CD154-independent rejection. J Immunol. 2004;172:1691–1698. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.3.1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Murakawa T, et al. Simultaneous LFA-1 and CD40 ligand antagonism prevents airway remodeling in orthotopic airway transplantation: implications for the role of respiratory epithelium as a modulator of fibrosis. J Immunol. 2005;174:3869–3879. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.7.3869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Arefanian H, et al. Combination of anti-CD4 with anti-LFA-1 and anti-CD154 monoclonal antibodies promotes long-term survival and function of neonatal porcine islet xenografts in spontaneously diabetic NOD mice. Cell Transplant. 2007;16:787–798. doi: 10.3727/000000007783465244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Kitchens WH, Haridas D, Wagener ME, Song M, Ford ML. Combined Costimulatory and Leukocyte Functional Antigen-1 Blockade Prevents Transplant Rejection Mediated by Heterologous Immune Memory Alloresponses. Transplantation. 2012 doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31824e75d7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Gibbons C, Sykes M. Manipulating the immune system for anti-tumor responses and transplant tolerance via mixed hematopoietic chimerism. Immunol Rev. 2008;223:334–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00636.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Wekerle T, et al. Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation with co-stimulatory blockade induces macrochimerism and tolerance without cytoreductive host treatment. Nat Med. 2000;6:464–469. doi: 10.1038/74731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Sykes M. Mixed chimerism and transplant tolerance. Immunity. 2001;14:417–424. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00122-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Kean LS, et al. Induction of Chimerism in Rhesus Macaques through Stem Cell Transplant and Costimulation Blockade-Based Immunosuppression. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:320–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Parker DC, et al. Survival of mouse pancreatic islet allografts in recipients treated with allogeneic small lymphocytes and antibody to CD40 ligand. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:9560–9564. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Markees TG, et al. Long-term survival of skin allografts induced by donor splenocytes and anti-CD154 antibody in thymectomized mice requires CD4(+) T cells, interferon-gamma, and CTLA4. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:2446–2455. doi: 10.1172/JCI2703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Taylor PA, Friedman TM, Korngold R, Noelle RJ, Blazar BR. Tolerance induction of alloreactive T cells via ex vivo blockade of the CD40:CD40L costimulatory pathway results in the generation of a potent immune regulatory cell. Blood. 2002;99:4601–4609. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.12.4601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Wang T, et al. Prevention of allograft tolerance by bacterial infection with Listeria monocytogenes. J Immunol. 2008;180:5991–5999. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.9.5991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Wang T, et al. Infection with the intracellular bacterium, Listeria monocytogenes, overrides established tolerance in a mouse cardiac allograft model. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:1524–1533. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03066.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Taylor PA, Lees CJ, Waldmann H, Noelle RJ, Blazar BR. Requirements for the promotion of allogeneic engraftment by anti-CD154 (anti-CD40L) monoclonal antibody under nonmyeloablative conditions. Blood. 2001;98:467–474. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.2.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Taylor PA, Noelle RJ, Blazar BR. CD4(+)CD25(+) immune regulatory cells are required for induction of tolerance to alloantigen via costimulatory blockade. J Exp Med. 2001;193:1311–1318. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.11.1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Kendal AR, et al. Sustained suppression by Foxp3+ regulatory T cells is vital for infectious transplantation tolerance. J Exp Med. 2011;208:2043–2053. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Zhai Y, Meng L, Gao F, Busuttil RW, Kupiec-Weglinski JW. Allograft rejection by primed/memory CD8+ T cells is CD154 blockade resistant: therapeutic implications for sensitized transplant recipients. J Immunol. 2002;169:4667–4673. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.8.4667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]