Abstract

Aims

To investigate the histological evolution in the development of pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis (PPFE).

Methods and results

We examined four patients who had undergone surgical lung biopsy twice, or who had undergone surgical lung biopsy and had been autopsied, and in whom the histological diagnosis of the first biopsy was not PPFE, but the diagnosis of the second biopsy or of the autopsy was PPFE. The histological patterns of the first biopsy were cellular and fibrotic interstitial pneumonia, cellular interstitial pneumonia (CIP) with organizing pneumonia, CIP with granulomas and acute lung injury in cases 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively. Septal elastosis was already present in the non-specific interstitial pneumonia-like histology of case 1, but a few additional years were necessary to reach consolidated subpleural fibroelastosis. In case 3, subpleural fibroelastosis was already present in the first biopsy, but only to a small extent. Twelve years later, it was replaced by a long band of fibroelastosis. The septal inflammation and fibrosis and airspace organization observed in the first biopsies were replaced by less cellular subpleural fibroelastosis within 3–12 years.

Conclusions

Interstitial inflammation or acute lung injury may be an initial step in the development of PPFE.

Keywords: acute lung injury, cellular interstitial pneumonia, idiopathic interstitial pneumonia, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, organizing pneumonia, pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis, pulmonary upper lobe fibrosis

Introduction

Pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis (PPFE) is a unique clinicopathological entity that was first described by Frankel et al.1 Idiopathic PPFE is now listed as one of the rare idiopathic interstitial pneumonias (IIPs) in the updated classification of IIPs.2 The concept of PPFE, regarding both clinical features and histopathology, overlaps with that of idiopathic pulmonary upper lobe fibrosis (PULF), which was described initially by Amitani et al.3 According to that description, idiopathic PULF has been considered to progress slowly, with 10–20 years of presentation. Recently, however, it has been disclosed that PPFE or PULF sometimes progresses rapidly, with a poor prognosis.4,5 Its pathogenesis appears to be heterogeneous.6

Regarding the evolution of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), it was once widely accepted that end-stage fibrosis is reached via an inflammatory process that starts at the early stage in the lung parenchyma. However, it is now believed that the inflammatory stage is not absolutely necessary for the development of fibrosis; that is, the fibrotic process that follows epithelial injuries could start in the initial stage of the disease, without inflammation.7 If this is so, what process intervenes in the progression to the established fibroelastosis in PPFE?

In 2013, Ofek et al.8 published an article that described PPFE as a pathological phenotype of restrictive allograft syndrome following lung transplantation. In that report, the authors showed that PPFE was often associated with diffuse alveolar damage (DAD), and their findings suggested a temporal sequence of DAD followed by the development of PPFE. We hypothesized that not only transplantation-associated PPFE, but also other forms of PPFE, idiopathic or secondary, may have an inflammatory or acute lung injury (ALI) process prior to the development of PPFE. In this article, we present four patients with PPFE who showed features of cellular and fibrotic interstitial pneumonia, cellular interstitial pneumonia (CIP) and an ALI pattern in the first biopsy, and subpleural fibroelastosis in the second biopsy or autopsy. Herein, we discuss the evolution of PPFE regarding the relationships between clinical characteristics and imaging and histological findings.

Materials and methods

We reviewed the medical files of all patients admitted to the Departments of Respiratory Medicine at the Fukuoka University Hospital, National Hospital Organization Fukuoka Higashi Medical Centre and Hamanomachi Hospital from 2006 to 2013, and selected four patients who had undergone surgical lung biopsy twice, or who had undergone surgical lung biopsy and had been autopsied, and in whom the main histological feature of the first biopsy was not PPFE, but the diagnosis of the second biopsy or autopsy was PPFE. Histological findings were reviewed in specimens stained with haematoxylin and eosin and with elastica van Gieson (EVG), to determine the histological differences between first biopsy and second biopsy or autopsy. Clinical data, including serum levels of Krebs von den Lungen-6 (KL-6) and imaging findings, were also reviewed. KL-6, a high molecular mass mucin-like glycoprotein, was originally identified by Kohno et al.,9 and has been reported to be a sensitive marker for interstitial lung diseases, such as IPF10 and non-specific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP).11 Serum levels of KL-6 in PPFE patients are reported to be around the normal upper limit, and tend to be elevated during the course of the disease. Alveolar epithelial cells are likely to be involved in the fibrotic process of the disease, as in other fibrosing or cellular IIPs.5,6

The institutional review board of Fukuoka University Hospital approved this retrospective study (#14-5-16).

Results

The clinical characteristics and laboratory data of the four patients are shown in Table1. Three of the four patients never smoked, and all patients were lean, with a body mass index of 16.9 ± 0.8 kg/m2 (mean ± standard error). The serum levels of KL-6 were 510 ± 104 U/ml, which is around the normal upper limit.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics and laboratory data

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at first onset (years) | 69 | 56 | 49 | 32 |

| Gender | Male | Male | Female | Female |

| Age at first surgical lung biopsy (years) | 69 | 56 | 49 | 32 |

| Age at second surgical lung biopsy (years) | – | – | 61 | – |

| Age at autopsy (years) | 73 | 62 | 35 | |

| Smoking status (pack-years) | Never-smoker | Smoker (40) | Never-smoker | Never-smoker |

| History of pneumothorax | No | No | No | Yes |

| Past history | NP | NP | NP | IPAH |

| Family history of interstitial pneumonia | No | No | No | No |

| Occupational history | Medical technologist | Welder for >25 years | Manager at a sushi bar | No occupational history |

| Administration of steroids | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 15.6 | 18.9 | 15.6 | 17.5 |

| First symptoms | Chest pain | Cough | Chest pain | Exercise dyspnoea |

| Crackles | Audible | Audible | Not audible | Not audible |

| Autoantibodies | No | No | No | No |

| KL-6 (U/ml) | 506 | 793 | 295 | 446 |

IPAH, Post-lung-transplanted state owing to idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension; KL-6, Krebs von den Lungen-6; NP, nothing particular.

Case 1

A 69-year-old man with chest pain visited our hospital. Chest computed tomography (CT) revealed ill-defined nodular opacities attached to the pleura in both the upper and lower lung fields. Six months later, one of the lesions in the right S5 was biopsied by video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS). Although alveolar architectures were mostly preserved histologically, alveolar septa were diffusely thickened, with fibrosis and a mild degree of mononuclear cell infiltration (Figure1A,B). The patient was then observed in the outpatient clinic. However, his general condition became gradually worse, with increasing dyspnoea. Multiple nodular opacities with fibrosis on chest CT were also advanced.

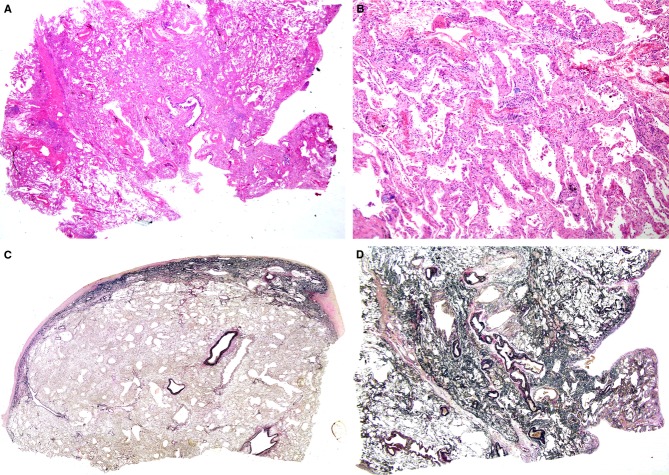

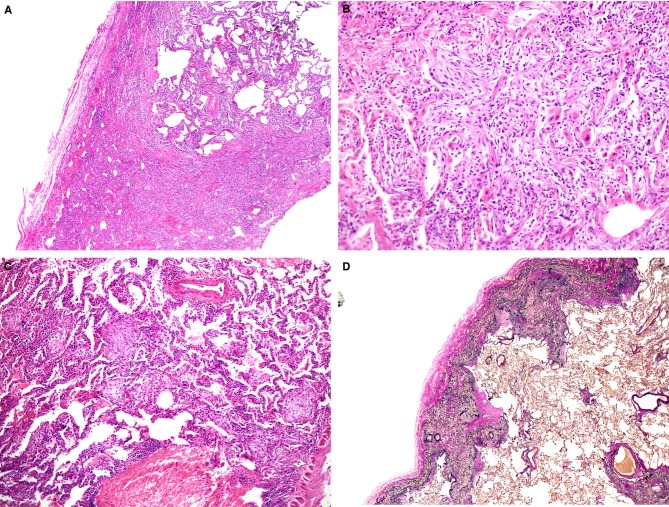

Figure 1.

A, A biopsy specimen from right S5 taken from a patient aged 69 years. Alveolar septa were diffusely thickened, with preservation of lung structure [haematoxylin and eosin (H&E)]. B, Alveolar septa were widened with septal fibrosis and a mild degree of inflammatory infiltration (H&E). C, An autopsy specimen taken from the right middle lobe, showing a fibroelastotic band just beneath the fibrously thickened pleura [elastica van Gieson (EVG)]. D, EVG staining of right S5 at biopsy. Lung parenchyma was rich in elastic fibres, with localized aggregates of elastic fibres and alveolar septal elastosis.

Three years and 7 months after the biopsy, the patient was admitted to our hospital. Corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide were administered, but without any beneficial effect. The patient died of rapidly progressive respiratory failure at 41 hospital days, and was autopsied. Autopsy revealed DAD, which seemed to be the direct cause of death. Just beneath the pleura thickened with collagen, there was a band-like gathering of elastic fibres. The border between the elastosis and the normal-appearing lung parenchyma was sharply demarcated (Figure1C). These features were consistent with those of PPFE. PPFE features were observed in all lobes of both lungs. We reviewed the biopsy specimen, and added another specimen stained with EVG, which demonstrated that alveolar septal elastosis was already present (Figure1D), albeit without band-like consolidated elastosis along the visceral pleura, which is a histological prototype of PPFE, as observed in the autopsy.

Case 2

A 56-year-old man presenting with cough and mild fever for 2 months underwent right lung biopsies (right S3, S6, and S9) by VATS. Chest CT showed small nodular opacities attached to the pleura in the bilateral apex, and subpleural ground-glass or reticular opacities mainly in the bilateral lower lobes (Figure2A). The patient had worked as a welder for >25 years, including stainless steel welding for 19 years. He had smoked 20 cigarettes a day for 37 years.

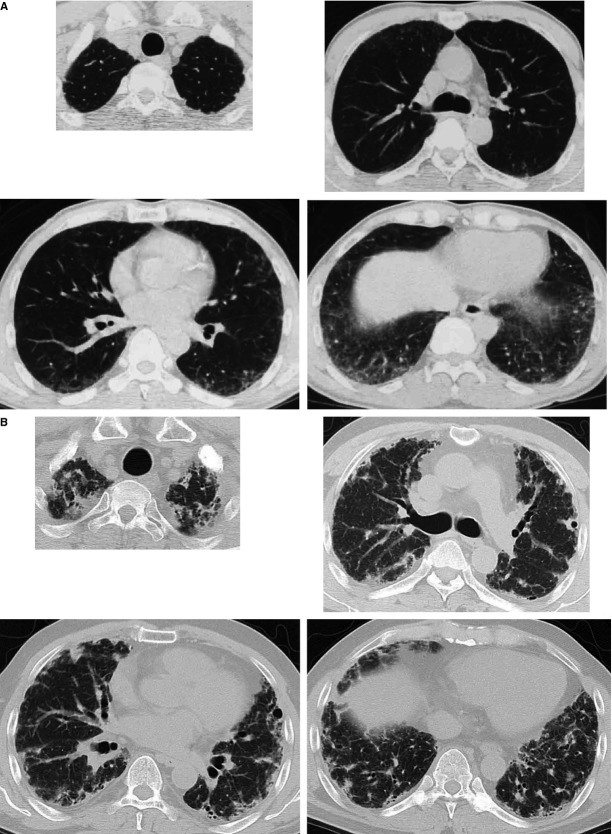

Figure 2.

A, Chest computed tomography (CT) scan taken at the age of 56 years, just before the biopsy. B, Chest CT scan taken at the age of 59 years, 3 years and 5 months after the biopsy.

A biopsy specimen taken from S3 showed that alveolar septa were uniformly thickened, with mononuclear cell infiltration; however, the lung architecture was preserved. S6 showed similar microscopic findings. However, in another biopsy specimen taken from S9, alveolar septa were more prominently infiltrated by mononuclear cells. In addition, septal fibrosis and airspace organization were present (Figure3A,B). The patient was treated with prednisolone and cyclosporine, without a favourable effect. Three years and 5 months after the biopsy, chest CT showed nodular, reticular and linear opacities with bullae distributed mainly in the subpleural areas of bilateral lungs (Figure2B). The patient's physical condition worsened gradually to severe respiratory failure.

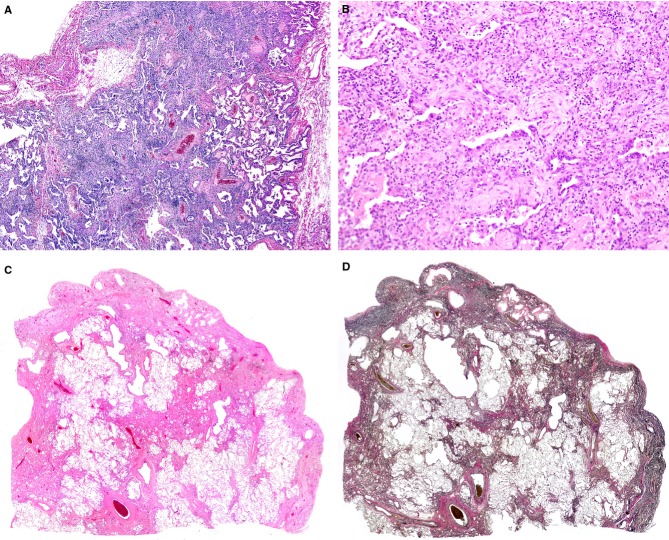

Figure 3.

A, A biopsy specimen from right S9 taken from a patient aged 56 years. Alveolar septa were densely infiltrated by mononuclear cells and widened [haematoxylin and eosin (H&E)]. B, Septal fibrosis and airspace organization (H&E). C, A histological specimen taken from the superior segment of the left upper lobe resected for lung transplantation at the age of 60 years (H&E). Lung parenchyma was less cellular than it was at the first biopsy. D, elastica van Gieson staining of the sample depicted in (C), showing subpleural fibroelastosis.

Four years and 2 months after the biopsy, the patient received a left lung transplant from a brain-dead donor. A histological specimen taken from the superior segment of the left upper lobe showed less cellular fibrosis located in the subpleural area, partly extending inside the lung parenchyma (Figure3C). EVG staining revealed that the fibrosis was coincident with the aggregation of elastic fibres, together with alveoli filled with mature collagen. Visceral pleurae were locally thickened with collagen (Figure3D). Other specimens taken from both the left upper and lower lobes showed similar findings. These histological features were compatible with those of PPFE.

The patient's forced expiratory volume in 1 s transiently recovered from 1160 to 1910 ml after the lung transplantation. However, bilateral diffuse ground-glass opacities appeared gradually, and the fibrotic shrinkage of his right lung progressed, with deterioration in his general condition. Two years and 7 months after lung transplantation, he died of respiratory failure and was autopsied. The autopsy confirmed the histological diagnosis of PPFE in the right lung. In addition, diffuse alveolar proteinosis was found. EVG staining was additionally performed for the biopsy specimens, but significant elastosis was not found.

Case 3

A 56-year-old woman visited our hospital complaining of left chest pain. Chest CT showed irregular pleural thickening or parenchymal nodular opacities attached to the pleura in the bilateral apex. During the subsequent 5-year follow-up without any treatment, nodular opacities gradually expanded, and her body weight decreased by 7 kg over a period of 10 years.

The patient underwent VATS biopsies of the superior and lingular segments of the upper lobe and lower lobes of the left lung at the age of 61 years. In the biopsied specimen of the superior segment of the upper lobe, a band-like aggregate of elastic fibres was observed just beneath the pleura, with a sharp demarcation with less-involved lung parenchyma (Figure4A) and with intra-alveolar collagenous fibrosis around the elastosis. These features were identical to those of PPFE. In the histological specimens taken from the lingular segment and the lower lobe, subpleural elastosis was minimal, with micro-honeycombing associated with the intervening deposition of collagen, consistent with the pattern of usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) rather than PPFE.

Figure 4.

A, A biopsy specimen from the superior segment of the left upper lobe taken from a patient aged 61 years, showing a typical feature of pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis [elastica van Gieson (EVG)]. B, A biopsy specimen from right S2 taken at the age of 49 years, showing cellular interstitial pneumonia with localized areas of subpleural fibrosis [haematoxylin and eosin (H&E)]. C, Higher magnification of (B) (indicated by a black arrow), showing a granuloma with giant cells adjacent to the subpleural fibrosis (H&E). D, EVG staining of the sample shown in (B), revealing subpleural fibrosis consisting of fibroelastosis.

The patient's past history revealed that she had undergone VATS biopsy at the age of 49 years in another hospital. Those biopsy specimens and their paraffin blocks were obtained, and additional histological specimens stained with EVG were prepared to compare the findings of the two biopsies. Biopsied specimens of right S2 showed CIP associated with a localized subpleural band of connective tissue (Figure4B). Small granulomas with giant cells were sparsely scattered at the border of the connective tissue band (Figure4C) and in the alveolar septa infiltrated by mononuclear cells. The histological findings of S4 were similar to those of S2, although they were less prominent in cellularity and without subpleural connective tissue bands. Although hypersensitivity pneumonitis was suspected, causative antigens were not identified. The fibrotic band was shown to be fibroelastosis by EVG staining (Figure4D).

Case 4

A 30-year-old woman with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension underwent living-donor lung transplantation, receiving a right lower lobe from her younger sister and a left lower lobe from her mother. Twenty-one months after the lung transplantation, the transplanted right lung was surgically biopsied because of progressive dyspnoea and the presence of ground-glass opacities in the upper lung field and interlobular septal thickening with peribronchiolar consolidation in the lower lung field of the right lung on chest CT. Open lung biopsy was performed from the lower parts of the transplanted lung. The biopsy specimen showed massive fibrosis and alveoli with septal thickening (Figure5A). Organizing connective tissues almost obliterated peripheral airways, intermingled with atypical epithelial cells with an eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure5B). These features were consistent with an ALI pattern. In another area, intra-alveolar organizing connective polyps were observed, with CIP (Figure5C).

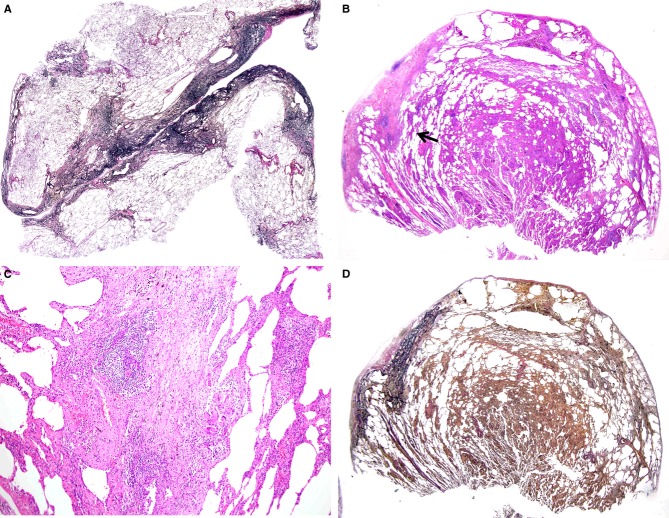

Figure 5.

A, A biopsy specimen from the lower part of the transplanted right lung, showing fibrosis and cellular interstitial pneumonia [haematoxylin and eosin (H&E)]. B, Higher-magnification view of the biopsied sample, showing an organizing diffuse alveolar damage pattern (H&E). C, Another area of the biopsied lung at higher magnification, showing an organizing pneumonia pattern (H&E). D, Lower part of the left lung at the autopsy showing subpleural fibroelastosis [elastica van Gieson (EVG)].

In spite of the high doses of corticosteroids administered, the patient's general condition worsened gradually, with increased bilateral interstitial opacities. She died 52 months after lung transplantation. At autopsy, both lungs showed a PPFE pattern (Figure5D). The autopsy findings have been reported elsewhere.12 Additional EVG staining for the biopsy specimens failed to reveal significant elastosis.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated four patients with PPFE confirmed by second biopsy or autopsy; however, the histological features of the first biopsies were considerably different from those of the final biopsies or autopsies.

In case 1, the interval between the biopsy and autopsy was 3 years and 7 months. As the PPFE pattern was observed in all lobes of bilateral lungs at autopsy, it is probable that the NSIP-like pattern observed in the biopsy evolved to subpleural bands of fibroelastosis; that is, alveoli with septal elastosis were gradually compressed, consolidated, and shifted to subpleural areas. Fibroelastosis was already present in the first biopsy, but another few years were required for completion of subpleural fibroelastosis, which is a histological hallmark of PPFE.

In case 2, clinical observations revealed the gradual, but seamless, exacerbation of the disease without imaging improvement, and a PPFE pattern was observed in all specimens taken from the resected left lung. Therefore, it is unlikely that PPFE occurred independently of the histological pattern, i.e. cellular and fibrotic interstitial pneumonia with organizing pneumonia (OP), observed in the biopsy. Prednisolone and cyclosporine seemed to cure the interstitial inflammation, but were unable to prevent disease progression.

Subpleural fibroelastosis was identified in both the first and second biopsies in case 3, but it was more widely distributed in the second biopsy. CIP with granulomas in the first biopsy was not present in the second biopsy. Although it cannot be denied that CIP with granulomas and PPFE arose independently, granulomas were often found at the edge of fibroelastosis, and were associated with the OP pattern observed in the first biopsy. It is possible that CIP, OP and granulomas were incorporated into the PPFE pattern. Reddy et al.4 reported a patient with coexistent PPFE and hypersensitivity pneumonitis in the lower lobe. Mycobacterial infection, such as that with Mycobacterium avium–intracellulare, is another possible explanation for the histology. However, repeated sputum examinations failed to identify the organisms. We previously reported a patient with PPFE complicated by M. avium infection.5

It is apparent that there was a close relationship between the ALI pattern observed in the biopsy and the PPFE pattern observed in the autopsy in case 4. Clinical observation proved that there was serial exacerbation of symptoms and signs in the period between the biopsy and the autopsy. In addition, repeated examination by CT demonstrated that ground-glass opacities at the apex were transformed into multiple cysts with nodular, reticular and interseptal linear opacities. These findings suggest a temporal sequence of ALI followed by the development of PPFE in the lung-transplanted patient, and were coincident with those observed by Ofek et al.8

We have shown in the present study that there is a possible temporal continuity in the histological features from interstitial inflammation and fibrosis or ALI to the development of PPFE. These histological alterations suggest that some inflammatory or lung injury processes might constitute the first step in the occurrence and progression of PPFE.

The most important aspect of our speculation is whether the histology of the autopsies or second biopsies of lungs truly reflects the ‘evolutionary process’ of the histology of lung tissues obtained in the first biopsy. The combination of upper lobe PPFE and lower lobe UIP4,5 patterns, and the combination of UIP and NSIP patterns in chronic fibrosing interstitial pneumonia,2,13 are not rare. As the sampling sites of the second biopsy or autopsy in our patients included the upper lobes, where initial lesions had existed, we think that histology at the second biopsy or autopsy was the result of the ‘evolutionary process’ of the first biopsy. Serial imaging findings also supported our hypothesis.

The second question is whether such a histological evolution is applicable to all types of PPFE generally. Our study was performed on the basis of clinical and histological analyses of only four patients, which is the major limitation of the present study. As PPFE is a rare interstitial pneumonia, large-scale studies of PPFE patients are necessary to confirm our results.

Honeycomb lung is a non-specific end-stage fibrosis of lung diseases such as IIPs, including UIP.14,15 Interstitial inflammation and fibrosis with or without granulomas and an ALI pattern as an initial stage might progress to honeycomb lung as an end-stage fibrosis of the interstitial lung diseases. Similarly, we propose subpleural fibroelastosis, considered to be a histological prototype of PPFE, as an end-stage fibrosis of PPFE, idiopathic or secondary, such as transplantation-associated PPFE. As we demonstrated in the present study that interstitial inflammation and fibrosis with or without granulomas and ALI were replaced by subpleural fibroelastosis at various time intervals, we speculate that these lesions could represent an initial step in the development of PPFE.

Pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis may be a healing reaction. However, PPFE is a distinctive form of chronic scarring in the lung that differs from the common scarring seen in IPF.16 PPFE lungs contain twice as much elastin as IPF lungs.17 Also, a histological healing reaction in PPFE does not necessarily mean clinical healing of PPFE. Extensive subpleural elastosis causes serious clinical problems, such as progressive restrictive ventilatory impairment associated with exertional dyspnoea. In that sense, PPFE is a disease entity.

The histological finding of elastosis is not exclusive to PPFE. Other IIPs also have increased amounts of elastic fibres. In the analysis of fibrosing process of IIPs, little attention has been directed to the elastic tissue.18,19 Idiopathic PPFE is now a member of the rare IIPs.2 We have to pay more attention to elastosis in IIPs, in order to determine any differences in elastosis between idiopathic PPFE and other IIPs, and to distinguish PPFE as a histological pattern from PPFE as a disease entity. PPFE as a histological pattern, which is true of the apical cap, does not require clinical symptoms and signs. On the other hand, PPFE as a true IIP is a clinical disease with characteristic clinical and physiological findings.

Reddy et al.4 showed underlying conditions in PPFE: recurrent pulmonary infections, and genetic and autoimmune mechanisms. However, we were unable to identify any of the predisposing causes or diseases described above or a previous history of malignancy1 (Table1).

In clinical practice, a diagnosis of PPFE is established only at an advanced stage, when subpleural fibroelastosis develops. At present, we cannot distinguish interstitial inflammation and ALI as initial lesions of PPFE from other inflammatory diseases until a typical PPFE pattern emerges. PPFE has been widely recognized among pulmonologists since the revised classification of IIPs appeared in 2013.2 Large-scale and long-term accumulation of patients with PPFE may be needed to elucidate the evolution of PPFE.

Acknowledgments

This work was partly supported by a grant to the Diffuse Lung Diseases Research Group from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan.

Author contributions

T. Hirota acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting and final approval of the manuscript. Y. Yoshida, M. Yoshimi, T. Harada, N. Tsuruta and H. Ishii acquisition of data and final approval of the manuscript. Y. Kitasato and M. Masato acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, and final approval of the manuscript. T. Koga, K. Nabeshima and N. Nagata analysis and interpretation of data, and final approval of the manuscript. M. Fujita acquisition and analysis of data, and final approval of the manuscript. K. Watanabe conception and design of the study, acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting and final approval of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Frankel SK, Cool CD, Lynch DA, Brown KK. Idiopathic pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis. Description of a novel clinicopathologic Entity. Chest. 2004;126:2007–2013. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.6.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travis WD, Costable U, Hansell DM, et al. An Official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Statement: update of the international multidisciplinary consensus classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2013;188:733–748. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201308-1483ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amitani R, Niimi A, Kuze F. Idiopathic pulmonary upper lobe fibrosis. Kokyu. 1992;11:693–699. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy TL, Tominaga M, Hansell DM, et al. Pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis; a spectrum of histopathological and imaging phenotypes. Eur. Respir. J. 2012;40:377–385. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00165111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe K, Nagata N, Kitasato Y, et al. Rapid decrease in vital capacity in patients with idiopathic pulmonary upper lobe fibrosis. Respir. Investig. 2012;50:88–97. doi: 10.1016/j.resinv.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe K. Pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis: its clinical characteristics. Curr. Respir. Med. Rev. 2013;9:229–237. doi: 10.2174/1573398X0904140129125307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher TM, Wells AU, Laurent GL. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: multiple causes and multiple mechanisms? Eur. Respir. J. 2007;30:835–839. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00069307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ofek E, Sato M, Saito T, et al. Restrictive allograft syndrome post lung transplantation is characterized by pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis. Mod. Pathol. 2013;26:350–356. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohno N, Akiyama M, Kyoizumi S, et al. A novel method for screening monoclonal antibodies reacting with antigenic determinants on soluble antigens; a reversed indirect-enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (RI-ELISA) Hiroshima J. Med. Sci. 1987;36:319–323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama A, Kohno N, Hamada H, et al. Circulating KL-6 predicts the outcome of rapidly progressive idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1998;158(5 Pt 1):1680–1684. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.5.9803115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii H, Mukae H, Kadota J, et al. High serum concentrations of surfactant protein A in usual interstitial pneumonia compared with non-specific interstitial pneumonia. Thorax. 2003;58:52–57. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.1.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirota T, Fujita M, Matsumoto T, et al. Pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis as a manifestation of chronic lung rejection? Eur. Respir. J. 2013;41:243–245. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00103912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flacherty KR, Travis WD, Colby TV, et al. Histopathologic variability in usual interstitial and nonspecific interstitial pneumonias. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2001;164:1722–1727. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.9.2103074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzenstein AA. Katzenstein and Askin's surgical pathology of non-neoplastic lung disease. 4th ed. Philadelpia: Saunders Elsevier; 2006. pp. 75–78. [Google Scholar]

- Corrin B, Nicholson AG. Pathology of the lungs. 3rd ed. London: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2011. p. 149. [Google Scholar]

- Camus P, Thüsen J, Hansell DM, et al. Pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis: one more walk on the wild side of drugs? Eur. Respir. J. 2014;44:289–296. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00088414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enomoto N, Kusagaya H, Oyama Y, et al. Quantitative analysis of lung elastic fibers in idiopathic pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis (IPPFE): comparison of clinical, radiological, and pathological findings with those of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) BMC Pulm. Med. 2014;14:91. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-14-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negri EM, Montes GS, Saldiva PHN, et al. Architectural remodelling in acute and chronic interstitial lung disease: fibrosis or fibroelastosis? Histopathology. 2000;37:393–401. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2000.00992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozin GF, Gomes MM, Parra ER, et al. Collagen and elastic system in the remodeling process of major types of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia (IIP) Histopathology. 2005;46:413–421. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2005.02103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]