Abstract

Background

Rotavirus infections are a major cause of diarrhea in children in both developed and developing countries. Rotavirus genetics, patient immunity, and environmental factors are thought to be related to the severity of acute diarrhea due to rotavirus in infants and young children. The objective of this study was to provide a correlation between rotavirus genotypes, clinical factors and degree of severity of acute diarrhea in children under 5 years old in Surabaya, Indonesia.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted in children aged 1–60 months with acute diarrhea hospitalized in Soetomo Hospital, Surabaya, Indonesia from April to December 2013. Rotavirus in stool specimens was identified by ELISA and genotyping (G-type and P-type) using multiplex reverse transcription PCR. Severity was measured using the Ruuska and Vesikari scoring system. The clinical factors were investigated included patient’s age (months), hydration, antibiotic administration, nutritional state, co-bacterial infection and co-viral infection.

Results

A total of 88 children met the criteria; 80.7% were aged 6–24 months, watery diarrhea was the most common type (77.3%) and 73.6% of the subjects were co-infected with bacteria, of which pathogenic Escherichia coli was the most common (42.5%). The predominant VP7 genotyping (G-type) was G2 (31.8%) and that of VP4 genotyping (P-type) was P[4] (31.8%). The predominant rotavirus genotype was G2P[4] (19.3%); G1P[4] and G9P[4] were uncommon with a prevalence of 4.5%. There were significant differences between the common genotype and uncommon genotype with respect to the total severity score of diarrhea (p <0.05). G3, G4 and G9 were significantly correlated with severe diarrhea (p = 0.009) in multivariate analyses and with frequency of diarrhea (>10 times a day) (p = 0.045) in univariate analyses, but there was no significant correlation between P typing and severity of diarrhea. For combination genotyping of G and P, G2P[4] was significantly correlated with severe diarrhea in multivariate analyses (p = 0.029).

Conclusions

There is a correlation between rotavirus genotype and severity of acute diarrhea in children. Genotype G2P[4] has the highest prevalence. G3, G4, G9 and G2P[4] combination genotype were found to be associated with severe diarrhea.

Keywords: Genotyping, Clinical factors, Rotavirus diarrhea, Pediatrics

Introduction

Pediatric diarrhea is often fatal since this disease results in severe dehydration [1]. There are several causes of pediatric diarrhea including bacterial or viral infectious diseases. As to the latter, several pathogens such as rotavirus, adenovirus and norovirus are reported [2-4]. Rotavirus is the most commonly isolated viral cause of severe diarrhea in infants, infecting more than 111 million pediatric patients every year and causing an estimated 440,000 deaths [4-6]. Rotavirus genetic factors, patient’s immune factors, and environmental factors are associated with the incidence and severity of acute diarrhea due to rotavirus in infants and toddlers [7].

Viral typing is necessary for characterizing rotavirus strains, especially focusing on different rotavirus seasons in different locations. G-typing is categorized as G1-16, the double combination of G1-16G1-16, and the triple combination G1-16G1-16G1-16 [8]. P-typing is classified to into P1-28, the double combination of P1-28P1-28, and triple combination of P1-28P1-28P1-28 [8]. Moreover, whole genotyping is sometimes shown as the combination of G type and P type [8]. VP7 and VP4 proteins are the basis of the classification of group A rotaviruses by G (VP7) and P (VP4) types; G represents glycoprotein and P represents protease sensitive protein [8,9]. G1P[8], G2P[4], G3P[8], and G4P[8] were the four dominant and most commonly found genotypes worldwide from 1994 to 2003 [10,11]. Generally, in human rotavirus, G1 to G4 and G9 in VP7 and P[4] and P[8] in VP4 are the most common types. Combined G and P typing represents a limited number of genotypes such as G2P[4], G3P[8], G4P[8], G9P[8], and G1P[8] [11]. Those types vary from region to region (e.g. G5 types in Brazil, G10 types in India) [12,13]. Till date 27 G genotypes, 37 P genotypes and 73 different combinations of G and P genotypes have been reported [14,15]. Putnam et al. found G9P [8] to be the most common genotype with a prevalence of 13.57% in 2003–2004 in Indonesia, but Soenarto et al. detected G1P[6] as the dominant genotype (34%) in Indonesia in 2006 [16,17]. New rotavirus genotypes have been found, causing more severe diarrhea than previously identified rotavirus genotypes [18-23].

Flores et al. studying the efficacy of rotavirus vaccine (RIT 4237) on diarrheal disease, formulated a scoring system for the severity of diarrhea in infants and toddlers with or without vaccination [24]. The scoring system was used by Cascio et al. to assess differences in the severity of diarrhea experienced by children in Italy who were infected by rotavirus of different strains [19]. Ruuska and Vesikari [22] developed the scoring system by combining more variables includes episodes of vomiting in 24 hours [25]. Its validity and reliability was verified with a significant correlation between scores and the impact of diarrheal disease on the family [26]. Mota-Hernandez et al. utilized such scoring system to assess the severity of diarrhea in children caused by rotavirus infection with different genotypes of VP4 gene, unidentified P type (new P type) and type P[8] [21]. Zhang et al. also stated that rotavirus diarrhea caused by G1 was associated with higher severity scores than diarrhea caused by G3 in their study of rotavirus genotypes and disease severity [27]. This scoring system was also used to assess the relationship between rotavirus genotypes and the severity of diarrhea in a population of children in India [28].

Host factors are also very important in infections. Immune status and nutrition affect host responses to bacterial and viral pathogens [29,30]. Compared to bacteria, the infectious potential of viruses in humans is comparative and the host’s defenses are essential for prevention [31,32]. Environmental issues such as drinking water, hand washing and family income also play a role in the prevention of infectious disease [33].

In this study, we sought the correlation between rotavirus genotypes, clinical factors and degree of severity of acute diarrhea in children under 5 years old in Surabaya, Indonesia.

Methods

Patients

For one year surveillance, the data and the stool samples were gathered from April to December 2013. A total of 220 stool specimens were collected from the inpatients diagnosed with acute diarrhea in the Department of Pediatrics, Soetomo Hospital, Surabaya, Indonesia. The stools samples were from the consecutive patients in this studied time. The children with chronic diarrheas were excluded from the study.

PCR examination was done in 88 patients who had positive immunochromatography tests for virus detection. The study was approved by the Health Research Ethics Committee of Soetomo Hospital. Research subjects were all patients hospitalized in the Gastroenterology Ward in Department of Pediatrics of Soetomo Hospital. Inclusion criteria: children between 1–60 months with positive results from rotavirus antigen examination. Patients were excluded from the study if they were treated with antibiotics, probiotics and zinc before hospitalization, or had a history of rotavirus immunization or were in an immunocompromized condition (eg. from long term steroid therapy or cytostatic agents), who refused to continue the study. All study subjects underwent a physical examination, and parents or caretakers filled out a questionnaire. Stool specimens were collected and sent to the laboratory in Institute of Tropical Disease within 24 hours for bacterial culture and rotavirus molecular biology studies.

Diagnoses of rotavirus

Stool rotavirus was examined by immunochromatographic methods (BD Rota/AdenoExamine™ kit), BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA. Stool samples were selected for rotavirus genotyping by a two-step RT-PCR method and included to the study by randomization from rotavirus positive stool samples [34]. The viral RNA was extracted using Viral Nucleic Acid Extraction Kit II (Geneaid Biotech Ltd., New Taipei) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Two-step reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) was carried out with the ThermoScript™ RT-PCR system to synthesize cDNA corresponding to the genomic segments encoding VP7 and VP4 with the protocol recommendation by the company. Used PCR primers are shown in Table 1. As to G typing, the primers VP7F and VP7R were used in RT-PCR (30 cycles) for an 881-bp VP7 gene segment. Then, VP7F was used in PCR (30 cycles) with type-specific such primers as aBT1 (G1), aCT-2 (G2), G3 (G3), aDT4 (G4), aAT8 (G8) and aFT9 (G9). For P-typing, the primers VP4F and VP4R were used in RT-PCR (30 cycles) for a 663-bp fragment and VP4F was then used in PCR (30 cycles) with such type-specific primers as 1T-1D (P[8]), 2T-1 (P[4]), 3T-1(P[6]), 4T-1 (P[9]) and 5T-1 (P[10]). Primers corresponding to the VP7 and VP4 genes for rotavirus genotyping were obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies, Singapore. All PCR products were separated in 2% agarose gel with a 50-bp DNA ladder as a standard marker and visualized by UV light after ethidium bromide-staining. All these procedures were performed according to the methods of WHO manuals [35].

Table 1.

Primers correspond to VP7 and VP4 genes for rotavirus genotyping

| Primer | Sequence (5′ – 3′) | Position | PCR product (bp) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G-typing (VP7) first amplification | ||||

| VP7-F | ATG TAT GGT ATT GAA TAT ACC AC | nt 51-71 | 881 | |

| VP7-R | AAC TTG CCA CCA TTT TTT CC | nt 914-932 | ||

| G-typing (VP7) second amplification | ||||

| G1 | aBT1 | CAA GTA CTC AAA TCA ATG ATG G | nt 314-335 | 618 |

| G2 | aCT2 | CAA TGA TAT TAA CAC ATT TTC TGT G | nt 411-435 | 521 |

| G3 | mG3 | ACG AAC TCA ACA CGA GAG G | nt 250-269 | 682 |

| G4 | aDT4 | CGT TTC TGG TGA GGA GTT G | nt 480-498 | 452 |

| G8 | aAT8 | GTC ACA CCA TTT GTA AAT TCG | nt 178-198 | 754 |

| G9 | mG9 | CTT GAT GTG ACT AYA AAT AC | nt 757-776 | 179 |

| P-typing (VP4) first amplification | ||||

| VP4-F | TAT GCT CCA GTN AAT TGG | nt 132-149 | 663 | |

| VP4-R | ATT GCA TTT CTT TCC ATA ATG | nt 775-795 | ||

| P-typing (VP4) second amplification | ||||

| P[4] | 2T-1 | CTA TTG TTA GAG GTT AGA GTC | nt 474–494 | 362 |

| P[6] | 3T-1 | TGT TGA TTA GTT GGA TTC AA | nt 259–278 | 146 |

| P[8] | 1T-1 | TCT ACT TGG ATA ACG TGC | nt 339 –356 | 224 |

| P[9] | 4T-1 | TGA GAC ATG CAA TTG GAC | nt 385–402 | 270 |

| P[10] | 5T-1 | ATC ATA GTT AGT AGT CGG | nt 575–594 | 462 |

References: [35].

Detection of co-infection with norovirus: xTAG® GPP assay

The xTAG® Gastrointestinal Pathogen Panel (xTAG®GPP) (Luminex corporation, Austin, TX) is a qualitative multiplex PCR assay to detect simultaneously 15 different pathogens including norovirus in human stool samples. Solid stool (100-150 μg), or 100 μl of liquid stool was added to a Bertin SK38 Soil Mix Bead tube (BioAmerica Inc., Miami, FL) containing 900 μl of NucliSENS lysis buffer (bioMérieux, Durham, NC) [36]. RNA isolation for the xTAG® GPP assay was performed on the QIAamp MinElute Virus Spin kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) [37]. A multiplex PCR was prepared by adding the xTAG GPP Primer Mix (Luminex corporation). PCR amplification cycling parameters were a reverse transcription (RT) step at 53°C for 20 min followed by an enzyme activation step at 95°C for 15 min and then 38 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 58°C for 30 s and 72°C for 30 s, and followed by a final elongation step at 72°C for 2 min [38]. Following the incubation of the RT-PCR products with the xTAG GPP bead mix, streptavidin-PE conjugate and xTAG reporter buffer (Luminex corporation), the mixture was allowed to hybridize in the thermocycler for 3 min at 63°C followed by 45 min at 45°C. Data acquisition and analysis was performed on the MAGPIX instrument using xPONENT 4.2 software: positive and negative results were linked to a ratio between the target median fluorescence intensity and the threshold. An internal control (bacteriophage MS2) was included in each specimen [39].

Detection of co-infection with bacteria

Regarding the method of detection of co-infection with bacteria, we performed conventional bacterial culture method using all the stool samples according to the previous work [35,40-44].

Clinical factors

Clinical factors that were associated with the rotavirus genotyping included patient’s age (months), parents’ education, source of drinking water, duration of diarrhea before hospitalization, type of diarrhea, family income (monthly), type of milk, frequency of diarrhea, cough, fever, antibiotic administration, body temperature, nutritional state, co-bacterial infection, co-infection of upper respiratory tract infection (URTI), results of bacterial culture, and co-viral infection.

Severity of diarrhea

The severity of diarrheal disease is related to clinical symptoms such as vomiting, the frequency of diarrhea, increase in body temperature, dehydration requiring intravenous rehydration fluid administration, the need for hospitalization, and the number of days the patient has been suffering from diarrhea. The diagnosis of the severity of diarrhea in this study was done at the time of recruitment of study subjects, which was when the diarrhea patients were admitted to the hospital. The severity of diarrhea was measured through the scoring system designed by Ruuska and Vesikari, which was tested for reliability and internal validity by Freedman, with Cronbach’s α = 0.7 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Parameters and Vesikari clinical scoring system

| Score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Diarrhea | ||||

| Frequency, per days | 1-3 | 4-5 | ≥6 | |

| Duration (days) | 1-4 | 5 | ≥6 | |

| Vomiting | ||||

| Frequency, per days | 0 | 1 | 2-4 | ≥5 |

| Duration (days) | 1 | 2 | ≥3 | |

| Body temperature (°C) | <37.0 | 37.1-38.4 | 38.5-38.9 | ≥39.0 |

| Dehydration | None (<5%) | 5-10% | >10% | |

| Treatment | None | ORS | Hospitalized | |

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS statistics 17.0 (WinWrap® Basic, Polar Engineering and Consulting). Descriptive statistics using means, medians, standard deviation and confidence intervals were performed on all variables where appropriate. Inferential analysis was performed using the chi square and t-test.

Results

Eighty-eight samples positive for rotavirus out of the 220 fecal samples were analyzed using immunochromatographic methods.

Patient characteristics

Patient characteristics are shown in Tables 3 and 4. In brief, 51 (58%) were male and 37 (42%) were female. The age (months) was 14.6 ± 11.0. The most prevalent family income was US$ 90–179 in 41 patients (46.6%), followed by US$ 45–89 in 31 patients (35.2%). The prevalent source of drinking water was mineral water in 50 patients (56.8%), followed by tap water in 33 patients (37.5%). Frequency of diarrhea was 6.22 ± 3.85 times a day. Cough was seen in 25 patients (28.4%) and fever was seen in 72 patients (81.8%). Type of milk was predominantly formula milk (48.9%) followed by breast feeding + formula milk (31.8%). Antibiotics were administered in 20 patients (22.7%). Nutrition status was assessed as normal (55.7%), wasted (17.0%) and severely wasted (21.6%).

Table 3.

Overview of clinical characteristics

| Variable | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age (months) | ||

| 1-5 | 8 | 9.1 |

| 6-23 | 71 | 80.7 |

| 24-60 | 9 | 10.2 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 51 | 58 |

| Female | 37 | 42 |

| Nutritional state | ||

| Severly wasted | 19 | 21.6 |

| Wasted | 15 | 17.0 |

| Normal | 50 | 56.9 |

| Overweight | 4 | 4.5 |

| Maternal education | ||

| Low | 11 | 12.5 |

| Mid | 65 | 73.9 |

| High | 12 | 13.6 |

| Breastfeeding state | ||

| Never | 13 | 14.8 |

| <6 months | 42 | 47.7 |

| 6-12 months | 15 | 17.0 |

| >12 months | 18 | 20.5 |

Table 4.

Clinical manifestations

| Variable | N | % | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of diarrhea (hours) | 55.54 | 30.73 | ||

| Diarrhea frequency over 24 hours (each) | 6.26 | 3.85 | ||

| Vomiting | 67 | 77.0 | ||

| Duration of vomiting (days) | 1.82 | 1.10 | ||

| Vomiting frequency over 24 hours (each) | 4.76 | 3.64 | ||

| Temperature (°C) | 37.45 | 0.73 | ||

| Type of diarrhea | ||||

| Watery | 68 | 77.3 | ||

| Loose | 19 | 21.6 | ||

| Bloody | 0 | 0 | ||

| Mucous | 1 | 1.1 | ||

| With URTI* (cough/cold) | 25 | 28.7 | ||

| Dehydration | ||||

| No dehydration | 0 | 0 | ||

| Some dehydration | 78 | 88.6 | ||

| Severe dehydration | 10 | 11.4 | ||

| Coinfections | 64 | 72.7 | ||

| Concomitant pathogens | ||||

| Eschelichia coli | 37 | 42.5 | ||

| Klebsiella spp. | 24 | 27.6 | ||

| Enterobacter spp. | 3 | 3.4 |

*URTI: Upper respiratory tract infection.

Co- infection pathogens

Co-bacterial infection was seen in 64 patients (72.7%). The most prevalent bacteria was Escherichia coli (37/64, 57.8%) followed by Klebsiella (24/64, 37.5%). Co-viral infection was seen in 20 patients (22.7%) with rota + noro seen in 17 patients (85.0%) and rota + adeno + noro seen in 3 patients (15.0%).

Rotavirus typing

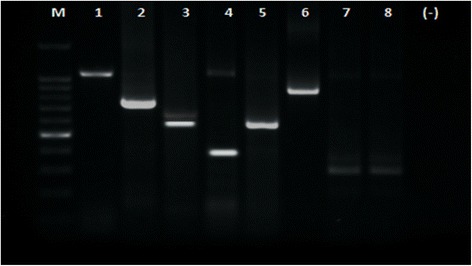

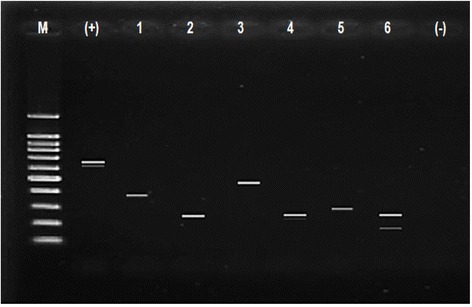

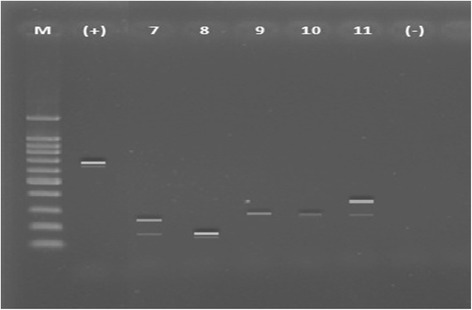

Rotavirus typing in VP7 and VP4 was classified as common (G1, G2, G3, G4 and G9 (VP7) and P[4], P[6] and P[8] (VP4)) and uncommon (others) typing. Common typing was detected in 68.2% in VP7 and in 85.2% in VP4. The predominant VP7 genotyping (G type) was G2 (31.8%), followed by G1 (29.5%), G9 (11.4%), G4G9 (8.0%), and G1G2 (4.6%). As to VP4 genotyping (P typing), P[4] was predominant (31.8%), followed by P[6] (27.3%), P[8] (26.1%), P[9] (4.5%) and P[6]P[8] (4.5%). The typing was confirmed by PCR (Figures 1, 2 and 3). Combinations of G and P typing were classified as common (G1P[6], G1P[8], G2P[4], G2P[6], G3P[6], G4P[6] and G4P[8]) or uncommon types as well. Common typing was detected in 52.3% (Table 5). Uncommon typing data are also shown in Table 5. The predominant common type was G2P[4] (19.3%), followed by G1P[6] (12.5%) and G1P[8] (11.4%). and the predominant uncommon types were G9P[4] (4.6%) and G1P[4] (4.5%).

Figure 1.

Gel electrophoreses from stool samples. PCR amplification result for G-type. Lane M: DNA Step Ladder marker, lane 1 (881 bp, full length VP7 RT-PCR product: positive control), lane 2 (G1, 618 bp), lane 4 (G4, 452 bp), lane 5 (G2, 521 bp), lane 6 (G3, 682 bp), lanes 7 and 8 (G9, 179 bp). (−): negative control.

Figure 2.

Gel electrophoreses from stool samples. PCR amplification result for P-type. Lane M (DNA Step Ladder), lane (+): positive control (663 bp, full length VP4 gene), lanes 1 (P[4], 362 bp), lanes 2 and 4 (P[8], 224 bp), lane 3 (P[10], 462 bp), lane 5 (P[9], 270 bp) and lane 6 (P[6]P[8], 146 bp and 224 bp). Lane (−): negative control.

Figure 3.

Gel electrophoreses from stool samples. PCR amplification result for P-type. Lane M (DNA Step Ladder), lane (+): positive control (663 bp, full length VP4 gene), lane 7 (P[6]P[8], 146 bp and 224 bp), lane 8 (P[6], 146 bp) , lane 9 and 10 (P[9], 270 bp), and lane 11 (P[4]P[9], 362 bp and 270 bp). Lanes (−): negative control.

Table 5.

Common and uncommon combination genotyping (G-type and P-type)

| Common genotyping | N | % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1P[8] | 10 | 11.4 | |||

| G1P[6] | 11 | 12.5 | |||

| G2P[4] | 17 | 19.3 | |||

| G2P[6] | 3 | 3.4 | |||

| G3P[6] | 2 | 2.3 | |||

| G4P[6] | 2 | 2.3 | |||

| G4P[8] | 1 | 1.1 | |||

| Subtotal | 46 | 52.3 | |||

| Uncommon genotyping | N | % | N | % | |

| G1P[4] | 4 | 4.5 | G2P[4]P[8] | 1 | 1.1 |

| G1G2P[6] | 2 | 2.3 | G2P[6]P[8] | 2 | 2.3 |

| G1G2P[8] | 2 | 2.3 | G4P[4] | 1 | 1.1 |

| G1G4G9P[8] | 1 | 1.1 | G4G9P[4] | 1 | 1.1 |

| G1G4P[4] | 1 | 1.1 | G4G9P[6] | 1 | 1.1 |

| G1G4P[6] | 1 | 1.1 | G4G9P[8] | 3 | 3.4 |

| G1G9P[8] | 1 | 1.1 | G4G9P[10] | 1 | 1.1 |

| G1P[4]P[8] | 1 | 1.1 | G4G9P[4]P[9] | 1 | 1.1 |

| G2P[8] | 2 | 2.3 | G9P[4] | 4 | 4.5 |

| G2P[9] | 2 | 2.3 | G9P[6] | 2 | 2.3 |

| G2G4P[8] | 1 | 1.1 | G9P[8] | 2 | 2.3 |

| G2G4P[9] | 2 | 2.3 | G9P[6]P[8] | 2 | 2.3 |

| G2P[10] | 1 | 1.1 | |||

| Subtotal | n = 42 | (47.7) | |||

Common genotype combination groups included 7 genotype variations and uncommon genotype groups included 25 genotype variations. G2P[4] genotypes predominated among the common genotype groups. The highest number of uncommon genotype groups found were G1P[4] and G9P[4]. Twenty-five variations of uncommon genotype combinations were found in small quantities (Table 5).

The total severity score for uncommon GP-type and uncommon G-type rotaviruses was higher than for common GP-type and common G-type with statistically significant differences. P-types showed no significantly differences in total severity score between common and uncommon genotype groups (Table 6).

Table 6.

Correlation of total severity score to rotavirus genotypes

| Variable | Type | N | Mean total score | SD | p-values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GP-type | Uncommon | 41 | 11.56 | 1.58 | 0.000 |

| Common | 47 | 9.06 | 1.82 | ||

| G-type | Uncommon | 28 | 12.00 | 1.41 | 0.000 |

| Common | 60 | 9.40 | 1.87 | ||

| P-type | Uncommon | 13 | 10.85 | 1.73 | 0.256* |

| Common | 75 | 10.12 | 2.17 |

*Mann–Whitney test, p < 0.05 (significant); bold: statistically significant.

Rotavirus typing and diarrhea

G3, G4 and G9 were significantly correlated with severe diarrhea (p = 0.009) in our multivariate analyses and with frequency of diarrhea (>10 times a day) (p = 0.045) in univariate analyses, but there was no significant correlation between P typing and severity of diarrhea. Regarding the combination of G and P typing, G2P[4] was significantly correlated with severe diarrhea in multivariate analyses (p = 0.029) (Tables 7, 8 and 9).

Table 7.

Correlation of severity of diarrhea with genotypes

| Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | N (%) | OR | p | OR | p |

| G1 | 34 (38.6) | 2.08 | 0.100 | ||

| G2 | 33 (37.5) | 0.25 | 0.004 | 0.36 | 0.089 |

| G3, G4, G9 | 30 (34.1) | 5.22 | 0.001 | 10.75 | 0.009 |

| P4 | 31 (35.2) | 0.85 | 0.722 | ||

| P6 | 28 (31.8) | 0.61 | 0.281 | ||

| P8 | 29 (33.0) | 1.93 | 0.154 | ||

| P9, P10 | 7 ( 8.0) | 1.51 | 0.605 | ||

Bold: statistically significant. OR: odds ratio.

Table 8.

Correlation of severity of diarrhea with combination genotypes

| Univariable | Multivariable | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | N (%) | OR | p | OR | p |

| G1P4 | 6 (6.8) | 6.08 | 0.106 | ||

| G1P6 | 14 (15.9) | 1.11 | 0.853 | ||

| G1P8 | 15 (17.0) | 1.31 | 0.634 | ||

| G1P9, G1P10 | 0 ( 0.0) | ||||

| G2P4 | 18 (20.5) | 0.94 | 0.003 | 0.95 | 0.029 |

| G2P6 | 7 ( 8.0) | 0.41 | 0.303 | ||

| G2P8 | 8 ( 9.1) | 3.67 | 0.125 | ||

| G2P9, G2P10 | 5 ( 5.7) | 0.72 | 0.723 | ||

| G3P4, G4P4, G9P4 | 10 (11.4) | 5.18 | 0.046 | 9.22 | 0.087 |

| G3P6, G4P6, G9P6 | 10 (11.4) | 1.11 | 0.879 | ||

| G3P8, G4P8, G9P8 | 11 (12.5) | 3.37 | 0.089 | ||

| G3P9, G3P10, G4P9, G4P10, G9P9, G9P10 | 4 (4.5) | 9.68 | 0.134 | ||

Bold: statistically significant. OR: odds ratio.

Table 9.

Correlation of G3, G4, and G9 genotypes with risk factors except for severity of diarrhea

| Univariate | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Risk factor | N (%) | OR | p |

| Gender (female) | 37 (42.0) | 1.08 | 0.860 |

| Age >10 years | 56 (63.6) | 1.53 | 0.374 |

| Co-infection with other virus | 20 (22.7) | 0.40 | 0.139 |

| Temperature (>38°C) | 26 (29.5) | 1.31 | 0.576 |

| Co-infection with bacteria | 64 (72.7) | 0.64 | 0.360 |

| Cough | 26 (29.5) | 1.31 | 0.576 |

| Type of diarrhea | 68 (77.3) | 1.74 | 0.333 |

| Frequency of diarrhea (>10 times a day) | 16 (18.2) | 3.12 | 0.045 |

| Hand-washing | 3 ( 3.4) | - | - |

| Mother hand-washing | 8 ( 9.1) | 1.18 | 0.831 |

| Vomiting | 68 (77.3) | 1.27 | 0.661 |

| Lavatory | 11 (12.5) | 1.73 | 0.399 |

| Fever | 72 (81.8) | 1.17 | 0.791 |

Bold: statistically significant.

Discussion

Rotavirus infection is a common cause of pediatric acute diarrhea especially in developing countries [4-6], and the most common cause of non-bacterial gastroenteritis in children not only in developing countries but also in developed countries. The positive rate for rotavirus varies between countries and regions, and the different detection rates may be explained by different study conditions, such as the season of the year or sampling methods.

We characterized the VP7 (G genotype) and VP4 (P genotype) gene segments in this study along with patients’ backgrounds and symptoms, and then identified the most common rotavirus combinations in our study. The rotavirus genotypes identified were very diverse. Genotypic variations were classified as common and uncommon based on descriptions by Kobayashi et al. [8]. We found genotype G2P[4] to be the dominant genotype with an overall prevalence of 19.3% in the subjects studied. As mentioned above, G1P[8], G2P[4], G3P[8], and G4P[8] were the four most common dominant genotypes in the world previously. The prevalence of each genotype was 52%, 11%, 3%, and 8% [10,11] respectively. These results differ from the studies by Sunarto et al. who found G1P[6] genotype as the dominant genotype [17]. Putnam et al. identified G2P[4] as the predominant genotype in the common genotype group, followed by G1P[6] [14]. Assuming a similarity in identification techniques, the difference in results may indicate that genotype prevalence in circulating rotaviruses may change periodically subject to natural fluctuations as reported by Gentsch et al. It is recommended that rotavirus vaccination programs conduct surveillance on an ongoing basis, including before and after implementation of vaccination programs [45]. Tate et al. suggested that the genotypes found to be circulating before the vaccination period should be used as a reference for the composition of the rotavirus vaccine, in order to produce vaccines with high efficacy [46]. Monitoring of genotypic variability after rotavirus vaccination makes it possible to identify genotypes that evolve in response to the selection pressure of the vaccine to emerge as new phenotypes that are immune to older vaccines. The emergence of immune genotypes has to be watched for and accommodated in the design of the next vaccines [31].

In this study, 64 subjects (72.7%) were found to be co-infected with bacteria. The commonest pathogen found concomitantly with rotavirus infection was E. coli. A systematic review by Grimprel et al. drawing on 173 English language journals from 1989 to 2006 reporting research in various countries around the world stated that the co-occurrence of diarrhea pathogen in the studied populations ranged from 0.3%–45.5%, and this range may reflect local epidemiology, economic development, and hygiene conditions [32]. A cohort study by Souza et al. in 154 children under 5 years suffering from acute diarrhea in Brazil revealed that 16.2% of rotavirus infections had co-infection with bacteria, particularly pathogenic E. coli [31].

Genotyping results were significantly associated with the severity of diarrhea using Vesikari symptom scores. In multivariate analyses, G3, G4 and G9 correlated significantly with severe diarrhea and frequent diarrhea and G2P[4] showed a significant correlation with severity of diarrhea. Further examination with longer periods of surveillance should be continued to monitor trends in this disease.

We would like to emphasize the limitations of this study. First, the number of cases and the study period are not enough to draw definitive conclusions. Nonetheless, these data are of importance since the studies in eastern Indonesia are lacking despite the prevalence of this disease in this region and its standing as a social issue in Indonesia. Secondly, seasonal data on viral isolation may show the trends in the spread of pathogens. Long-term regional surveillance is needed to overcome these limitations.

Conclusions

The present study reports the current situation for acute diarrhea caused by rotavirus in infants or younger children in east Indonesia, Surabaya. Genotype G2P[4] has the highest prevalence, and G3, G4 and G9 and G2P[4] combination genotype were found to be associated with severe and frequent diarrhea. Further long-term studies as well as surveillance programs are necessary for overcoming rotaviral disease.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the program of the Japan Initiative for Global Research Network on Infectious Diseases (J-GRID); by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

SS: carried out taking samples. KS: carried out drafting manuscripts. AA: carried out PCR and taking patients’ data. KO: carried out statistical analysis. OW: carried out taking samples. AD: carried out PCR and taking patients’ data. RR: carried out taking patients’ data. DR: carried out PCR. SA and MF: supervision. TS: supervision and taking samples. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Subijanto Marto Sudarmo, Email: subijantoms@gmail.com.

Katsumi Shigemura, Email: yutoshunta@hotmail.co.jp.

Alpha Fardah Athiyyah, Email: alpha-f-a@fk.unair.ac.id.

Kayo Osawa, Email: osawak@kobe-u.ac.jp.

Oktavian Prasetia Wardana, Email: droktavian97@gmail.com.

Andy Darma, Email: andarma@gmail.com.

Reza Ranuh, Email: rezagunadi@gmail.com.

Dadik Raharjo, Email: dadik_tdc@yahoo.co.id.

Soichi Arakawa, Email: soichi@med.kobe-u.ac.jp.

Masato Fujisawa, Email: masato@med.kobe-u.ac.jp.

Toshiro Shirakawa, Email: toshiro@med.kobe-u.ac.jp.

References

- 1.UNICEF/WHO . Diarrhoea: Why children are still dying and what can be done. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kosek M, Bern C, Guerrant RL. The global burden of diarrhoeal disease, as estimated from studies published between 1992 and 2000. Bull World Health Organ. 2003;81(3):197–204. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilhelmi I, Roman E, Sanchez-Fauquier A. Viruses causing gastroenteritis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2003;9(4):247–62. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2003.00560.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fodha I, Chouikha A, Peenze I, Beer MD, Dewar J, Geyer A, et al. Identification of viral agents causing diarrhea among children in the Eastern Center of Tunisia. J Med Virol. 2006;78(9):1198–203. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parashar UD, Hummelman EG, Bresee JS, Miller MA, Glass RI. Global illness and deaths caused by rotavirus disease in children. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9(5):565–72. doi: 10.3201/eid0905.020562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO . Diarrhoeal disease: fact sheets. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Listiyaningsih E. Role of rotavirus genetic factors to severity of acute infectious diarrhea in infants and toddlers on Indonesia [Indonesian] Jakarta: Digilib Universitas Indonesia; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kobayashi N, Ishino M, Wang Y-H, Chawla-Sarkar M, Krishnan T, Naik TN. Diversity of G-type and P-type of human and animal rotaviruses and its genetic background. Communicating Curr Res Educ Top Trends Appl Microbiol. 2007;FORMATEX:847–58. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rahman M, Matthijnssens J, Nahar S, Podder G, Sack DA, Azim T, et al. Characterization of a novel P[25], G11 human group A rotavirus. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(7):3208–12. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.7.3208-3212.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Santos N, Hoshino Y. Global distribution of rotavirus serotypes/genotypes and its implication for the development and implementation of an effective rotavirus vaccine. Rev Med Virol. 2005;15(1):29–56. doi: 10.1002/rmv.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Endara P, Trueba G, Solberg OD, Bates SJ, Ponce K, Cevallos W, et al. Symptomatic and subclinical infection with rotavirus P[8]G9, rural Ecuador. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13(4):574–80. doi: 10.3201/eid1304.061285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carmona RC, Timenetsky Mdo C, Morillo SG, Richtzenhain LJ. Human rotavirus serotype G9, São Paulo, Brazil, 1996–2003. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(6):963–8. doi: 10.3201/eid1206.060307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mukherjee A, Ghosh S, Bagchi P, Dutta D, Chattopadhyay S, Kobayashi N, et al. Full genomic analyses of human rotavirus G4P[4], G4P[6], G9P[19] and G10P[6] strains from North-eastern India: evidence for interspecies transmission and complex reassortment events. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17(9):1343–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matthijnssens J, Ciarlet M, McDonald SM, Attoui H, Bányai K, Brister JR, et al. Uniformity of rotavirus strain nomenclature proposed by the Rotavirus Classification Working Group (RCWG) Arch Virol. 2011;156(8):1397–413. doi: 10.1007/s00705-011-1006-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trojnar E, Sachsenröder J, Twardziok S, Reetz J, Otto PH, Johne R. Identification of an avian group A rotavirus containing a novel VP4 gene with a close relationship to those of mammalian rotaviruses. J Gen Virol. 2013;94(Pt 1):136–42. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.047381-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Putnam SD, Sedyaningsih ER, Listiyaningsih E, Pulungsih SP, Komalarini Soenarto Y, et al. Group A rotavirus-associated diarrhea in children seeking treatment in Indonesia. J Clin Virol. 2007;40(4):289–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soenarto Y, Aman AT, Bakri A, Waluya H, Firmansyah A, Kadim M, et al. Burden of severe rotavirus diarrhea in Indonesia. J Infect Dis. 2009;200(s1):S188–94. doi: 10.1086/605338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bern C, Unicomb L, Gentsch JR, Banul N, Yunus M, Sack RB, et al. Rotavirus diarrhea in Bangladeshi children: correlation of disease severity with serotypes. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30(12):3234–8. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.12.3234-3238.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cascio A, Vizzi E, Alaimo C, Arista S. Rotavirus gastroenteritis in Italian children: can severity of symptoms be related to the infecting virus? Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32(8):1126–32. doi: 10.1086/319744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iturriza-Gomara M, Isherwood B, Desselberger U, Gray J. Reassortment in vivo:driving force for diversity of human rotavirus strains isolated in the united kingdom between 1995 and 1999. J Virol. 2001;75(8):3696–705. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.8.3696-3705.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mota-Hernandez F, Jose Calva J, Gutierrez-Camacho C, Villa-Contreras S, Arias CF, Padilla-Noriega L, et al. Rotavirus diarrhea severity is related to the VP4 type in Mexican children. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41(7):3158–62. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.7.3158-3162.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Linhares AC, Verstraeten T, Bosch JW-v, Clemens R, Breuer T. Rotavirus serotype G9 is associated with more-severe disease in Latin America. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43(3):312–4. doi: 10.1086/505493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rahman M, Sultana R, Ahmed G, Nahar S, Hassan ZM, Saiada F, et al. Prevalence of G2P[4] and G12P[6] rotavirus, Bangladesh. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13(1):18–24. doi: 10.3201/eid1301.060910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Flores J, Gonzales M, Perez M, Cunto W, Perez-Schael I, Garcia D, et al. Protection against severe rotavirus diarrhea by rhesus rotavirus vaccine in Venezuelan infants. Lancet. 1987;1(8538):882–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(87)92858-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruuska T, Vesikari T. Rotavirus disease in Finnish children: use of numerical scores for clinical severity of diarrhoeal episodes. Scand J Infect Dis. 1990;22(3):259–67. doi: 10.3109/00365549009027046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Freedman SB, Eltorky M, Gorelick M. Evaluation of a gastroenteritis severity score for use in outpatient settings. Pediatrics. 2010;125(6):e1278–85. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang LJ, Fang ZY, Zeng G, Steele D, Jiang BM, Kilgore PR. Relationship between severity of rotavirus diarrhea and serotype G and genotype. Zhonghua Shi Yan He Lin Chuang Bing Du Xue Za Zhi. 2007;21(2):144–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kang G. Rotavirus genotypes and severity of diarrheal disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43(3):315–6. doi: 10.1086/505500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Masrizal MA. Effects of protein-energy malnutrition on the immune system. Makara, Sains. 2003;7(2):69–73. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Janssen R, Krogfelt KA, Cawthraw SA, van Pelt W, Wagenaar JA, Owen RJ. Host-pathogen interactions in campylobacter infections: the host perspective. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21(3):505–18. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00055-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Souza EC, Martinez MB, Taddei CR, Mukai L, Gilio AE, Racz ML, et al. Etiologic profile of acute diarrhea in children in São Paulo. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2002;78(1):31–8. doi: 10.2223/JPED.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grimprel E, Rodrigo C, Desselberger U. Rotavirus disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27(Supplement):S3–10. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31815eedfa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wagstaff A, Bustreo F, Bryce J, Claeson M. WHO–World Bank Child Health. Child health: reaching the poor. Am J Public Health (N Y) 2004;94(5):726–36. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.94.5.726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murray PR, Baron EJ, Jorgensen JH, Landry ML, Pfaller MA. Manual of Clinical Microbiology. 9. Washington DC: ASM Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manual of rotavirus detection and characterization methods, Immunization, Vaccines and Biologicals, WHO, WHO/IVB/08.17. Geneva, Switzerland; 2009.

- 36.Boom R, Sol CJ, Salimans MM, Jansen CL, Wertheim-van Dillen PM, van der Noordaa J. Rapid and simple method for purification of nucleic acids. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28(3):495–503. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.3.495-503.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gibson KE, Schwab KJ. Detection of bacterial indicators and human and bovine enteric viruses in surface water and groundwater sources potentially impacted by animal and human wastes in lower Yakima valley, Washington. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77(1):355–62. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01407-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Freeman MM, Kerin T, Hull J, McCaustland K, Gentsch J. Enhancement of detection and quantification of rotavirus in stool using a modified real-time RT-PCR assay. J Med Virol. 2008;80(8):1489–96. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Navidad JF, Griswold DJ, Gradus MS, Bhattacharyya S. Evaluation of luminex xTAG gastrointestinal pathogen analyte specific reagents for high-throughput, simultaneous detection of bacteria, viruses, and parasites of clinical and public health importance. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51(9):3018–24. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00896-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Atlas RM. Handbook of Microbiological Media. 2. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press Inc.; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Forbes BA, Sahm DF, Weissfeld AS. Bailey & Scott’s Diagnostic - Microbiology. 11. St. Louis, Missouri: Mosby Elsevier Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Isenberg HD. Clinical Microbiology Procedures Handbook. Washington DC: ASM press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mahon CR, Manuselis G. Textbook of Diagnostic Microbiology. 2. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Saunders; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Murray PR, Baron EJ, Jorgrnsen JH, Pfaller MA, Yoken RH. Manual of Clinical Microbiology. 8. Washington DC: ASM Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gentsch JR, Parashar UD, Glass RI. Impact of rotavirus vaccination: the importance of monitoring strains. Future Microbiol. 2009;4(10):1231–4. doi: 10.2217/fmb.09.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tate JE, Patel MM, Cortese MM, Lopman BA, Gentsch JR, Fleming J, et al. Remaining issues and challenges for rotavirus vaccine in preventing global childhood diarrheal morbidity and mortality. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2012;11(2):211–20. doi: 10.1586/erv.11.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]