Abstract

Regulatory T (Treg) cells suppress the development of inflammatory disease, but our knowledge of transcriptional regulators that control this function remains incomplete. Here we show that expression of Id2 and Id3 in Treg cells was required to suppress development of fatal inflammatory disease. We found that T cell antigen receptor (TCR)-driven signaling initially decreased the abundance of Id3, which led to the activation of a follicular regulatory T (TFR) cell–specific transcription signature. However, sustained lower abundance of Id2 and Id3 interfered with proper development of TFR cells. Depletion of Id2 and Id3 expression in Treg cells resulted in compromised maintenance and localization of the Treg cell population. Thus, Id2 and Id3 enforce TFR cell checkpoints and control the maintenance and homing of Treg cells.

Homeostasis of the immune system requires careful control mechanisms at mucosal barriers, sites exposed to abundant foreign antigens. Immune system cells must provide protection against a broad range of invading pathogens but also ensure tolerance to self antigens and innocuous non-self antigens1–3. Failure of the immune system to enforce tolerance readily leads to the development of autoimmune disease and allergies, including asthma and atopic dermatitis. Allergy is characterized by the expression of TH2 cell cytokines, high concentrations of serum immunoglobulin E (IgE) and eosinophilia4,5. Treg cells are prominent among the cell types that suppress spontaneous inflammation and are characterized by expression of the transcription factor Foxp3 (refs. 6–11). Absence of Foxp3 in mice and FOXP3 in humans rapidly results in the development of multiorgan autoimmunity, inflammatory bowel disease and allergy. Treg cells develop in the thymus (tTreg cells) as well as in the peripheral organs (pTreg cells)1–3. pTreg cells act primarily to control the development of mucosal inflammation12. Treg cells are also essential in regulation of humoral immunity; loss of Treg cells leads to elevated concentrations of autoantibodies, hyper-IgE syndrome, increased numbers of follicular helper T (TFH) cells and spontaneous development of germinal centers (GCs)13. Recent studies have identified a subset of Treg cells named TFR cells that control GC reactions, characterized by the expression of Cxcr5, Bcl6, Pdcd1 and Prdm1 (refs. 14–16).

Members of the helix-loop-helix (HLH) family regulate many developmental trajectories in the thymus17. These include E proteins as well as Id proteins. E proteins function as transcriptional activators or repressors with the ability to bind specific DNA sequences termed E-box sites. Four E proteins have been identified and characterized: E12, E47, HEB and E2-2. E12 and E47 are encoded by the Tcf3 locus and are generated by differential splicing18. HEB and E2-2 are related to the Tcf3 gene products but diverge substantially in the N-terminal transactivation domains. DNA-binding activity of E proteins is regulated by the Id proteins19,20. Four Id proteins named Id1, Id2, Id3 and Id4 contain an HLH dimerization domain but lack the basic DNA-binding region. Interactions between Id proteins and E proteins suppress DNA-binding activity of E proteins. Id2 and Id3 are particularly important in modulating the developmental progression of T lineage cells21–26.

Here we found that depletion of Id2 and Id3 expression in Treg cells resulted in the early onset of fatal TH2 cell–mediated inflammatory disease. We found that upon TCR-mediated signaling in Treg cells, expression of Id2 and Id3 declined, leading to higher binding activity of E proteins and induction of a TFR cell–specific program of gene expression, including Cxcr5 and Il10. Loss of Id2 and Id3 in Treg cells resulted in compromised Treg cell homeostasis, increased susceptibility to cell death upon stimulation and aberrant tissue localization. Taken together, we propose that Id2 and Id3 maintain the Treg cell pool and act as gatekeepers to enforce multiple checkpoints during TFR cell differentiation.

RESULTS

Id2 and Id3 expression in Treg cells

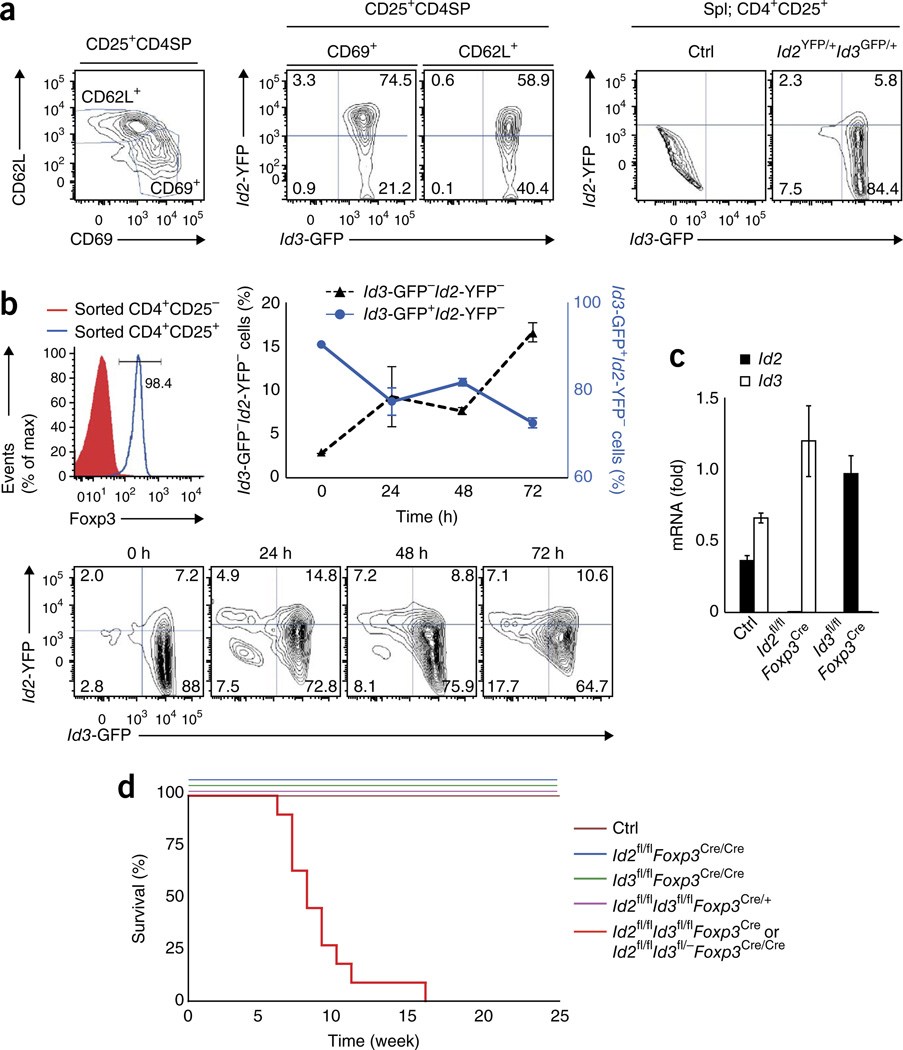

As a first approach to explore potential roles for Id2 and Id3 in Treg cells, we analyzed their expression patterns using Id2-YFP and Id3-GFP reporter mice26,27. We found that the thymic Treg cell population can be segregated into Id2+Id3+ as well as Id2−Id3+ compartments (Fig. 1a). In maturing Treg cells, which first express CD69 and then upregulate CD62L, Id2 expression declined, leading to an increase of the Id2−Id3+ compartment (Fig. 1a). In the peripheral lymphoid organs, the majority of Treg cells consisted of Id2−Id3+ cells (Fig. 1a). To examine the dynamics of Id2 and Id3 expression upon stimulation, sorted Treg cells carrying the Id2-YFP and Id3-GFP reporters were activated in vitro by exposure to anti-CD3e and anti-CD28 in the presence of non–Treg cells as well as antigen-presenting cells (APCs) (Fig. 1b). The most pronounced change occurred in Id3 expression, which declined substantially upon exposure to TCR-mediated signaling (Fig. 1b). Thus, the majority of Treg cells isolated from peripheral organs expressed abundant Id3 but lacked Id2, but upon in vitro stimulation, Id3 expression declined in a fraction of cells, leading to Id2loId3lo and Id2intId3lo Treg cell populations.

Figure 1.

Ablation of Id2 and Id3 expression in Treg cells leads to the early onset of fatal inflammatory disease. (a) Flow cytometric analysis of CD69 versus CD62L expression gated on the CD4+CD25+ Treg cell population derived from the thymus (CD4+CD25+CD8−TCRβhi (left). CD4SP, CD4+CD8−. GFP versus YFP expression, gated on CD69+CD62L− or CD69−CD62L+ Treg cells derived from the thymus (middle). GFP versus YFP expression in CD4+CD25+ Treg cells isolated from the spleens (Spl) of control and Id2YFP/+Id3GFP/+ mice (right). Numbers in quadrants indicate percent cells in each compartment. (b) Flow cytometric analysis of Foxp3 expression on sorted CD4+CD25+ and CD4+CD25− T cells (left; number indicates the percentage of Foxp3+ cells gated on the CD4+CD25+ T cells); sorted CD4+CD25+ Treg cells from Id2YFP/+Id3GFP/+ mouse (CD45.2) were cocultured with CD4+CD25− T cells (CD45.1) and stimulated with anti-CD3ε plus anti-CD28 in the presence of T cell–depleted splenocytes (APCs). Flow cytometric analysis of GFP versus YFP expression gated on CD45.2+CD45.1−CD4+TCRβ+CD25+ cells for the indicated time points (bottom). Percentage of Id3-GFP+Id2-YFP− cells and Id3-GFPId2-YFP−cells (middle). (c) Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of Id2 and Id3 transcript levels in sorted CD4+TCRβ+CD25+YFP+ Treg cells derived from the lymph nodes of Id2+/+Id3+/+Foxp3Cre (Ctrl), Id2fl/flFoxp3Cre or Id3fl/flFoxp3Cre mice. (d) Survival plot of Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre and Id2fl/flId3fl/−Foxp3Cre/CreId2fl/flFoxp3Cre/CreId3fl/flFoxp3Cre/CreId2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre/+ and littermate control (Ctrl) mice, monitored during a 25-week period. Data are representative of two experiments (a,b; error bars in b, s.d.; n = 3 technical replicates), one experiment (c; error bars, s.d.; n = 3 technical replicates) and one experiment (d; n = 11 independent biological replicates per group).

Id2 and Id3 expression suppresses fatal inflammation

To evaluate the roles of Id2 and Id3 in Treg cell function, we crossed Id2loxP/loxP (Id2fl/fl) and Id3fl/fl mice with Foxp3Cre mice23,28,29. The Foxp3Cre mice used throughout this study carried an internal ribosomal entry site followed by a sequence encoding a Cre-YFP functional fusion protein located downstream of the Foxp3 termination codon29. The Foxp3 locus is X chromosome–linked, and consequently gender-based differences in excision of the loxP-flanked alleles impact the population of Treg cells present in these mice. Here will refer to male mice carrying the Foxp3-Cre-YFP allele as Foxp3Cre mice and to female mice as Foxp3Cre/Cre or Foxp3Cre/+ mice. Mice deficient for Id2 or Id3 alone in Treg cells did not show evidence of inflammatory disease (Supplementary Fig. 1 and data not shown). To examine whether Id2 and Id3 compensate for each other, we sorted Treg cells from Id2fl/flFoxp3Cre mice as well as Id3fl/flFoxp3Cre mice. We isolated RNA from the sorted populations and examined it by real-time PCR for Id2 and Id3 expression. In the absence of Id2 expression, the abundance of Id3 increased, whereas in Treg cells deficient for Id3 expression, abundance of Id2 increased, as compared to controls (Fig. 1c).

Next, we generated Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre as well as Id2fl/flId3fl/fl Foxp3Cre/Cre mice. Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre and Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre/Cre mice were born with Mendelian frequencies and were healthy up to 4 weeks of age. However, 6–8-week-old mice with no sex bias developed dermatitis with swelling and fur loss across the eyelids, and the majority of Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre and Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre/Cre mice died within ten weeks (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 2a). Neither Id2fl/+Id3fl/flFoxp3Cre nor Id2fl/flId3fl/+Foxp3Cre mice displayed early morbidity (data not shown). Approximately one-third of Id2fl/ flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre and Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre/Cre mice showed intense dermatitis with scaling and fur loss throughout the body but not in the skin of the tail (data not shown). Similar to the case with human atopic dermatitis, Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre mice displayed dermatitis as evidenced by compulsive scratching of the face and back (Supplementary Video 1).

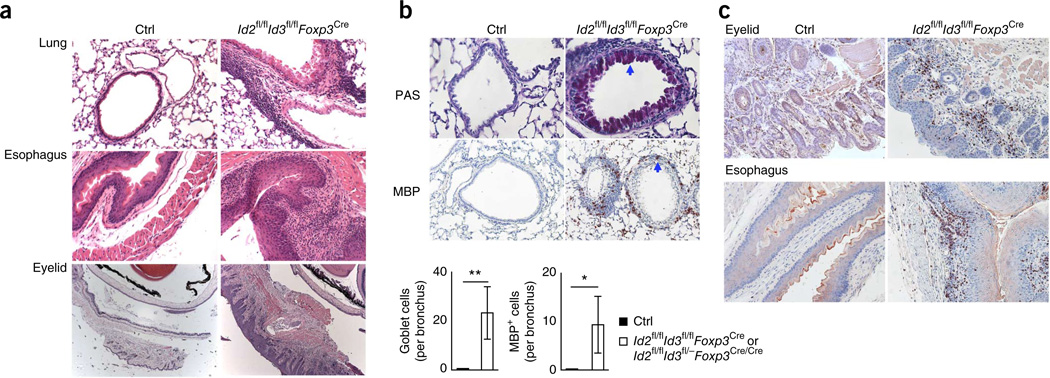

Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre and Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre/Cre mice also showed splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy of subcutaneous lymph nodes accompanied by increasing cell numbers, whereas the size of mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs) was comparable to that of littermate control mice (Supplementary Fig. 2a,b). As the Foxp3 locus is located on the X chromosome, half of the Treg cells in heterozygous female mice that carry one copy of Foxp3Cre express normal amounts of Id2 and Id3 (ref. 30). We found that heterozygous female Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre/+ mice lacked dermatitis across the eyelids, lacked detectable splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy, and had normal percentages of naive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Supplementary Fig. 2c,d and data not shown). Histological analysis of tissue samples from Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre and Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre/Cre mice revealed leukocytic infiltrates in the lung, esophagus and eyelids, with an associated reactive hyperplasia of the adjacent mucosal epithelial cells (Fig. 2a). The inflammatory infiltrates in the eyelid were localized to the subepithelial area and there was no inflammation in the lachrymal gland (Supplementary Fig. 3a). The inflammatory infiltrates in the lungs were peribronchial and perivascular, accompanied by production of mucus in the bronchial mucosal goblet cells (Fig. 2b). Many of the peribronchial and perivascular infiltrates of inflammatory cells in the lungs of Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre and Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre/Cre mice displayed expression of major basic protein (MBP), indicative of eosinophils, accompanied by infiltrating B cells and T cells (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 3b). In a similar fashion, inflammatory infiltrates across subepithelial regions of eyelids and the esophagus of Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre as well as Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre/Cre mice were composed primarily of eosinophils (Fig. 2c). We also found considerable eosinophilic infiltration in the hilar lymph nodes as well in the pancreas but not across the pancreatic islands (Supplementary Fig. 3c,d). We did not observe esophagitis in Foxp3 mutant mice, which indicated that pathologies associated with de pletion of Id2 and Id3 expression differ from that observed in mice lacking Foxp3 (Supplementary Fig. 3e). Notably, the larger bronchioles were filled with denuded epithelial cells and cell debris in dying Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre and Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre/Cre mice (Supplementary Fig. 3a).

Figure 2.

Spontaneous inflammation in the lung, eyelid, skin and esophagus in mice depleted for the expression of Id2 and Id3 in Treg cells. (a) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of the lung, esophagus and eyelid derived from control (Ctrl; female Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre/+) and Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre mice. Original magnification: ×200 (lung), ×200 (esophagus) and ×50 (eyelid). (b) Periodic acid Schiff (PAS) staining and MBP immunostaining of lungs of indicated genotypes (top; arrows indicate muous-producing goblet cell (PAS staining) and MBP-positive eosinophil). Original magnification: ×400 (PAS) and ×200 (MBP). Quantification of PAS-stained epithelial cells per bronchus or MBP-positive eosinophils in peribronchial area (bottom). (c) MBP staining of eyelid and esophagus. Original magnification: ×200 (eyelid) and ×200 (esophagus). Data are representative of six experiments (a), two experiments (b; mean ± s.d. (n = 4 biological replicates) and two experiments (c). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test).

In a minor fraction of mice (<20%), other organs such as liver, kidney, stomach, pancreas and colon displayed low levels of inflammation (data not shown). Notably, three of five Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre mice that survived beyond 12 weeks of age showed evidence of focal pneumonia, characterized by areas in the lung that were filled with eosinophilic foamy macrophages, and had scarring and increased deposition of collagen surrounding the bronchioles (Supplementary Fig. 4). We also observed mild to moderate colitis with an increase in numbers of mucosal MBP-expressing eosinophils (Supplementary Fig. 4).

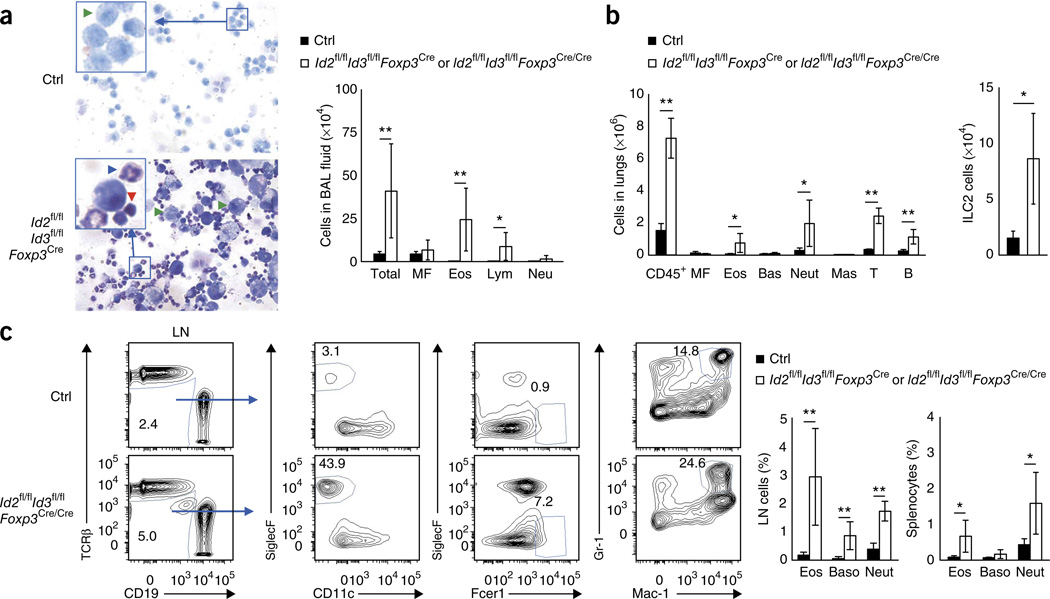

Consistent with the pathology in the lung, we found an increase in the total number of eosinophils and lymphocytes in the bronchial alveolar lavage (BAL) fluid and markedly elevated numbers of eosinophils, neutrophils, T cells and B cells in the lung derived from Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre and Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre/Cre mice (Fig. 3a,b). The increase in eosinophil cellularity in the lung was closely associated with elevated numbers of type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2) (Fig. 3b)31–33. In addition, we observed substantially increased numbers of eosinophils, basophils and neutrophils in the lymph nodes and spleen derived from Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre and Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre/Cre mice as compared to littermate control mice (Fig. 3c). These observations indicate that the absence of Id2 and Id3 expression in Treg cells leads to spontaneous TH2 cell–mediated fatal airway inflammation in the lungs as well as inflammation of the eyelids, the skin and the esophagus.

Figure 3.

TH2 cell–mediated inflammation in the lungs of mice depleted for Id2 and Id3 expression in Treg cells. (a) May-Giemsa staining images of cells (left) and cell numbers (right) in BAL fluid derived from 6–8-week-old control (Ctrl) or Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre mice (left). Green, red and blue arrowheads indicate macrophages (MF), lymphocytes (Lym) and eosinophils (Eos), respectively; Neu, neutrophil. Insets show magnification of boxed areas. Original magnification, ×40 (×120 in insets). (b) Numbers of hematopoietic cells (CD45+), macrophages (MF), eosinophils (Eos), basophils (Bas), neutrophils (Neu), mast cells (Mas), T cells (T) and B cells (B) isolated from the left lobes of the lungs derived from Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre mice (left). Numbers of type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2; CD45+LineageCD25+IL7R+Sca1hiThy1.2hi) isolated from the left lobes of the lungs derived from Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre mice (right). (c) Flow cytometric analysis of CD19 versus TCRβ expression of cells derived from the LNs isolated from 6–8-week-old control (Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre/+) or Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre/Cre mice. Adjacent panels indicate CD11c versus SiglecF, Fcer1 versus SiglecF and Mac-1 versus Gr-1 expression, gated on the TCRβ−CD19− compartment derived from 6–8-week-old control (Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre/+) or Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre/Cre lymphocytes isolated from subcutaneous LNs. Numbers in plots indicate percent CD19−TCRβ−, CD11c−SiglecF+, Fcer1+SiglecF− and Mac-1+Gr-1+ cells. Right, percentages of eosinophils (SiglecF+CD11c−), basophils (Baso; Fcer1hiSiglecF−) and neutrophils (Neut; Mac-1hiGr-1hi) in subcutaneous LN cells and splenocytes. Data are representative of four experiments (a,c; mean ± s.d.; in a, n = 8 independent biological replicates; in b, control n = 5, Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cren = 4 independent biological replicates; in c, control n = 6, Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cren = 9 independent biological replicates). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test).

Id2 and Id3 suppress TH2-mediated inflammation

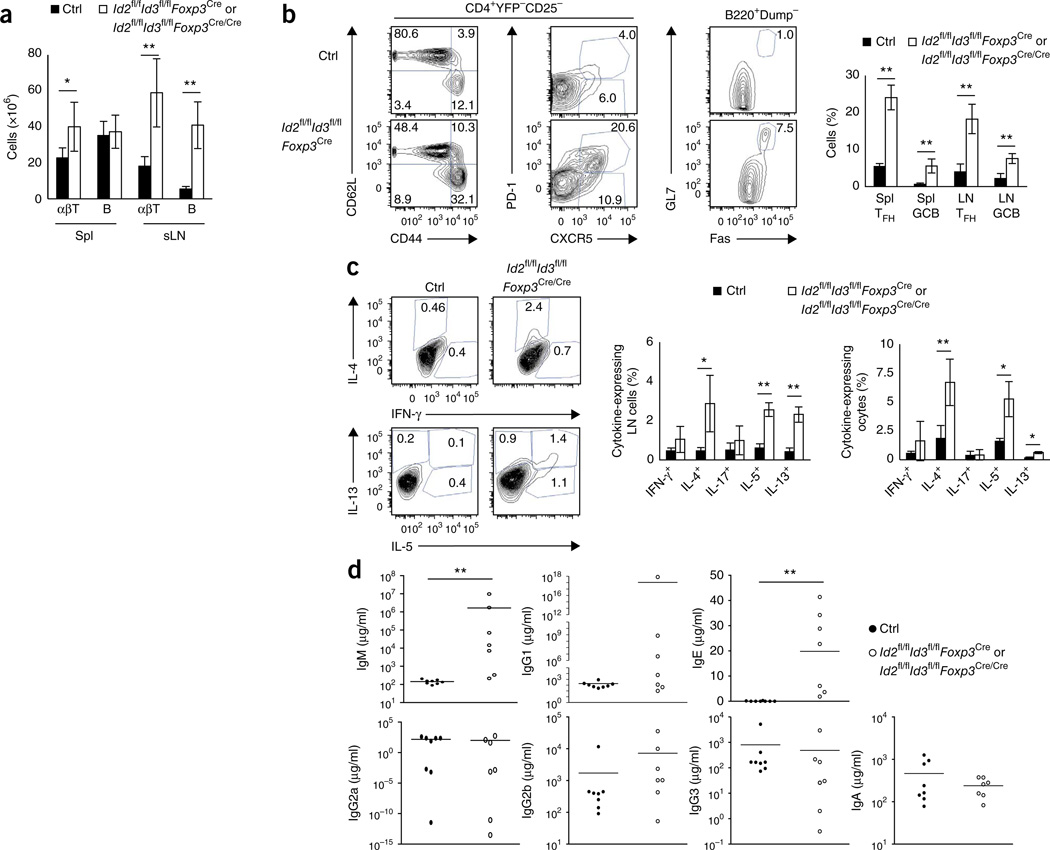

To determine how depletion of Id2 and Id3 expression in Treg cells leads to inflammatory disease, we examined the lymphoid organs. We noticed increased numbers of T cells and B cells in the spleen and subcutaneous LNs, in which we observed lower percentages of CD62LhiCD44lo naive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells as well as a significant increase in the percentages of TFH cells, GC B cells and IgG1 class–switched B cells (Fig. 4a,b and data not shown). We observed a substantial increase in TH2 cell–mediated production of cytokines, such as interleukin 4 (IL-4), IL-5 and IL-13 in the lymph nodes and spleen derived from Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre mice (Fig. 4c). Consistent with the markedly increased numbers of TFH cells and GC B cells, and the augmented expression of TH2 cell cytokines, 6–8-week-old Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre mice exhibited a spontaneous increase in IgM, IgG1 and IgE serum concentrations but not in IgG2b, IgG3 and IgA (Fig. 4d). Titers of anti-nuclear antibodies in serum isolated from Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre mice, however, were comparable to those in the littermate control (data not shown). These data indicate that expression of Id2 and Id3 in Treg cells is required to suppress spontaneous GC development and TH2 cell–mediated inflammatory disease.

Figure 4.

Spontaneous germinal center formation and TH2 cell-mediated inflammation in mice depleted for the expression of Id2 and Id3 in Treg cells. (a) αβ T cell (αβT) and B cell numbers for spleen (Spl) and subcutaneous LN (sLN) isolated from 8-week-old littermate control and Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre mice. (b) Flow cytometric analysis of splenocytes derived from 8-week-old littermate control (Id2fl/+Id3fl/+Foxp3Cre) and Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre mice, showing expression of CD44 versus CD62L and CXCR5 versus PD-1, gated on the CD4+TCR[3+YFP−CD25− population (left). Frequency of germinal center B cells in 8-week-old littermate control (Id2fl/+Id3fl/+Foxp3Cre) and Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre mice (middle). Numbers in quadrants and gates indicate percent cells in each compartment. Frequencies of TFH (CXCR5hiPD-1hi) cells in the CD4+ T cell compartment and GC B (FashiGL7hi) cells (GCB) in the B cell compartment (right). (c) Cytokine expression in CD4+ T cell derived from littermate control (Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre/+) and Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre/Cre mice (left) Percentages of CD4+ T cells producing IL-4, L-5, IL-13, IFN-γ and IL-17 in 7–9-week- old mice for the indicated genotypes (right). (d) Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) of IgM, IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, IgG3, IgA and IgE in serum derived from 6–9-week-old mice for the indicated genotypes. Data are representative of four experiments (a; mean ± s.d.; n = 8 biological replicates), | three independent experiments (b; mean ± s.d.; control n = 4, Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre n = 5 biological replicates), two experiments (c; mean ± s.d.; n = 4 biological replicates), one experiment (d; mean ± s.d.; control n = 8, Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cren = 7 biological replicates) *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test).

Id2 and Id3 modulate CXCR5 and Foxp3 expression

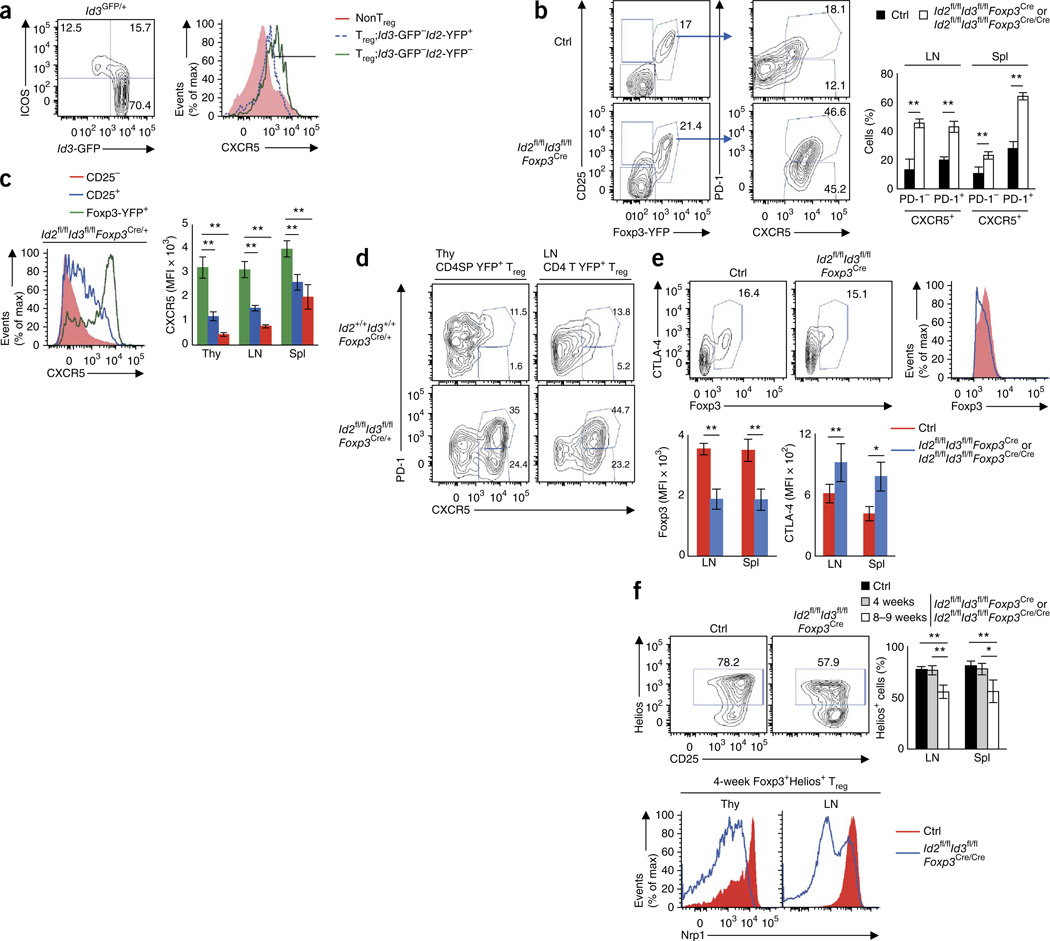

The Treg population can be segregated into distinct functional subsets, including effector Treg (eTreg) cells34. Previously, low Id3 expression has been observed in the Blimp-1+ eTreg cell population35. Consistent with these observations, we found that a fraction of ICOS+ eTreg cells displayed low Id3 expression and Id2loId3lo Treg cells expressed more CXCR5 (Fig. 5a). In line with this, Treg cells that lacked Id2 and Id3 expression exhibited increased expression of CXCR5, PD-1, ICOS, CXCR3, CXCR4 and CTLA-4 but decreased CD62L expression as compared to Id-sufficient Treg cells (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 5a–c)36. Treg cells derived from healthy heterozygous female Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre/+ mice also displayed increased expression of CXCR5 and PD-1, but expression of CXCR3, CXCR4, CD62L and CTLA-4 was comparable to that in wild-type Treg cells (Fig. 5c,d and Supplementary Fig. 5a–c). Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre mice displayed significantly reduced expression of Foxp3 protein (Fig. 5e). We observed this downregulation of Foxp3 even in heterozygous female Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre/+ mice, although abundance of Foxp3 transcript in Treg cells isolated from Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre/+ mice did not differ from that for Id2+/+Id3+/+Foxp3Cre/+ mice (Supplementary Fig. 5d,e). These data indicate that loss of Id2 and Id3 expression in Treg cells leads to decreased abundance of Foxp3 and increased proportions of CXCR5+PD-1+ Treg cells.

Figure 5.

Depletion of Id2 and Id3 expression in Treg cells modulates the expression of CXCR5, Foxp3 and Nrp1. (a) Flow cytometric analysis of Id3-GFP versus ICOS, gated on the CD4+CD25+ Treg cell compartment derived from from Id3gfp/+ splenocytes (left). Numbers in quadrants indicate percent cells in each compartment. Expression of CXCR5 in the Treg compartments as characterized by the expression of Id2 and Id3 (right). (b) Flow cytometric analysis of Treg cells (Foxp3-YFP+CD25+CD4) derived from LNs isolated from 8-week-old control (Id2fl/+Id3fl/+Foxp3Cre) and Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre mice for indicated cell surface markers. Numbers in plots indicate percent Foxp3-YFP+CD25+, CXCR5+PD-1+ and CXCR5+PD-1− cells. Spl, spleen. (c) CXCR5 expression patterns for YFP+Treg, CD25+YFP−Treg and CD25−non-Treg CD4+CD8− thymocytes derived from heterozygous female Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre/+ mice (left). CXCR5 expression derived from Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre/+ mice (bottom). MFI, mean fluorescence intensity. (d) CXCR5 and PD-1 expression in Treg cells derived from the thymus and LNs isolated from control Id2+/+Id3+/+Foxp3Cre/+ and Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre/+ mice. Numbers in plots indicate percent CXCR5+PD-1+ and CXCR5+PD-1− cells. (e) Flow cytometric analysis for Foxp3 and CTLA-4 expression in CD4 T cells derived from littermate control and Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre mice. Numbers in plots indicate percent Foxp3+ cells. (f) Helios and CD25 expression (top) and Nrp1 (bottom) in Foxp3+ or Foxp3+Helios+ Treg cells derived from 8-week-old control and Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre LNs and thymi. Numbers in plots indicate percent Helios+ cells. Percentages of Helios+ cells in Foxp3+ Treg cells isolated from control, 4-week-old or 8–9-week-old Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre mice (right). Data are representative of two experiments (a), three independent experiments (b; mean ± s.d.; control n = 3, Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cren = 5 biological replicates), two experiments (c; mean ± s.d.; n = 3 biological replicates), three experiments (d), three (Foxp3) and five (CTLA-4) experiments (e; mean ± s.d.; Foxp3 n = 3, CTLA-4 control n = 7, Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cren = 9 biological replicates), and three experiments (f; mean ± s.d.; n = 4 biological replicates). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test).

Recent studies have indicated that Treg cells generated in the thymus (tTreg cells) abundantly express Helios or Neuropilin-1 (Nrp1)37,38. We found that the proportions of Helios+ Treg cells were comparable between 4-week-old Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre mice versus control mice but reduced in 8–9-week-old Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre as compared to control mice. These data indicate that Id2 and Id3 maintain the Helios+ Treg cell pool (Fig. 5f). Recent observations also have indicated a critical role for Nrp1 expression in maintaining stability of Treg cells in inflammatory sites39. We found that Nrp1 expression was substantially reduced in Treg cells derived from Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre mice or Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre/+ mice (Fig. 5f and Supplementary Fig. 5f). These data indicate that the expression of a subset of genes associated with Treg cell function, including CXCR5, PD-1, Foxp3 and Nrp1, are directly affected by loss of Id2 and Id3 expression.

Id2 and Id3 expression affects Treg cell localization

Data described above indicate that loss of Id2 and Id3 expression leads to the abnormal proportions of Treg cells that express CXCR5. To explore the possibility that aberrant expression of CXCR5 affects localization and/or homing of Treg cells, we examined the localization of Treg cells in spleens from control or Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre and Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre/Cre mice. Increased numbers of Foxp3+ cells were localized to the B cell area in the spleens derived from Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre mice versus control mice (Supplementary Fig. 6). Treg cells depleted for Id2 and Id3 expression also appeared to home more deeply into the B cell follicles across LNs (Supplementary Fig. 6). To examine how depletion of Id2 and Id3 expression affects Treg localization across the lung tissues, we analyzed Treg cells derived from 4-week-old and 7–8-week-old Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre mice. Whereas the Foxp3+ pool was not significantly affected in the lungs derived from healthy 4-week-old Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre mice, the percentage of Foxp3 Treg cells localized across the lungs in 7–8-week-old Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre mice was significantly decreased (Supplementary Fig. 7a). To compare the abilities of Treg cells deficient for Id2 and Id3 expression to home to the lymphoid organs versus lung tissues, we transferred Treg cells isolated from heterozygous female Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre/+ mice into wild-type CD45.1 recipient mice. We found that the homing potential of Treg cells depleted for Id2 and Id3 expression was reduced in the lung, as compared to the lymph nodes or spleen (Supplementary Fig. 7b).

Roles of Id2 and Id3 in Treg-mediated immunosuppression

To determine whether the development of fatal TH2 cell–mediated inflammation upon depletion of Id2 and Id3 expression in Treg cells was caused by loss of suppressive functions of Treg cells, we examined the in vitro suppressive function of Treg cells sorted from 4-week-old Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre or Foxp3Cre mice. We found that Treg cells depleted for Id2 and Id3 expression displayed normal in vitro immunosuppressive function (Supplementary Fig. 8).

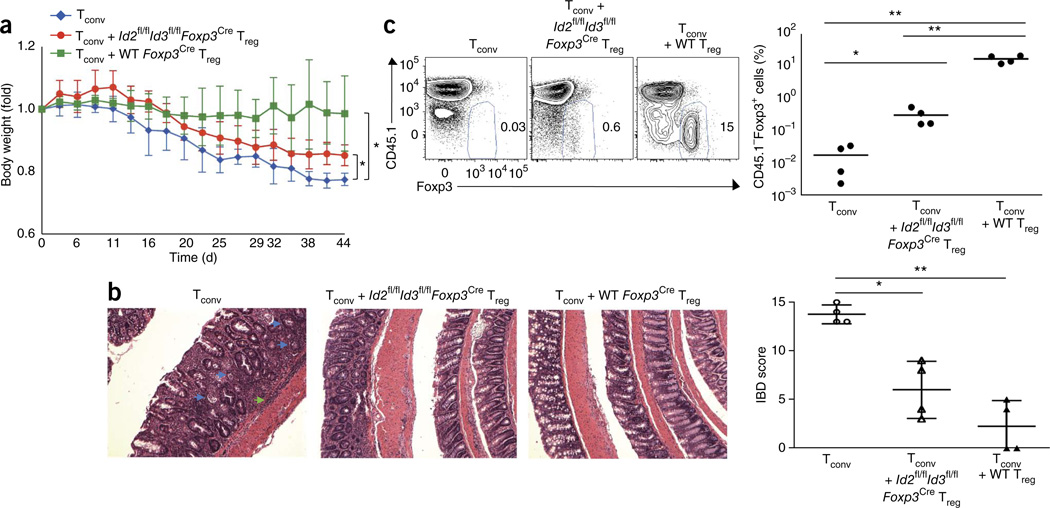

To examine whether Treg cells depleted for Id2 and Id3 expression have the ability to suppress T cell–mediated inflammation in vivo, we injected sorted CD4+CD25−CD45RBhi T cells (Tconv cells) derived from CD45.1 mice into Rag1−/− recipient mice with or without purified Treg cells isolated from 4-week-old Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre or Foxp3Cre mice (Fig. 6a). As expected, Rag1−/− recipient mice transferred with Tconv cells alone showed severe colitis accompanied by body-weight loss (Fig. 6a,b). Cotransfer of Treg cells isolated from Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre mice resulted in partially impaired suppressive activity (Fig. 6a,b). As expected, we found a large fraction of CD45.1−Foxp3+ Treg cells in the MLNs of recipient mice but fewer Id-deficient Treg cells in the MLNs of recipient mice (Fig. 6c). These findings are consistent with the notion that expression of Id2 and Id3 is required to maintain the Treg pool. Overall these data indicate that Treg cells depleted for Id2 and Id3 expression have the ability to suppress, albeit partially, T cell– mediated inflammation in a transfer colitis model.

Figure 6.

Impaired homeostasis of Treg cells deleted for Id2 and Id3 expression after transfer into Rag1−/− mice. (a) Body weight in indicated populations of mice after CD4+CD25−CD45RBhi T cell (Tconv) from CD45.1 mice were intravenously injected into Rag1−/− recipient mice with or without CD4+CD25+Foxp3-YFP+ T cell (Treg) from 4-week-old Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre or wild-type Foxp3Cre mice (CD45.2) (n = 4 each group). WT, wild type. (b) H&E staining of large intestine (left). Blue and green arrowheads indicate crypt abscess and infiltration of inflammatory cells in the submucosal muscle layer, respectively. IBD score50 in large intestine on day 44 after transfer (right). Original magnification, ×100 (c) Flow cytometric analysis of Foxp3 and CD45.1 expression gated on CD4+TCRβ+ cells in mesenteric LNs (left) and analysis of CD45.1Foxp3+ cells (right). Data are representative of one experiment (a–c; error bars, s.d.; n = 4 independent biological replicates). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test).

Id2 and Id3 maintain Treg cell homeostatic potential

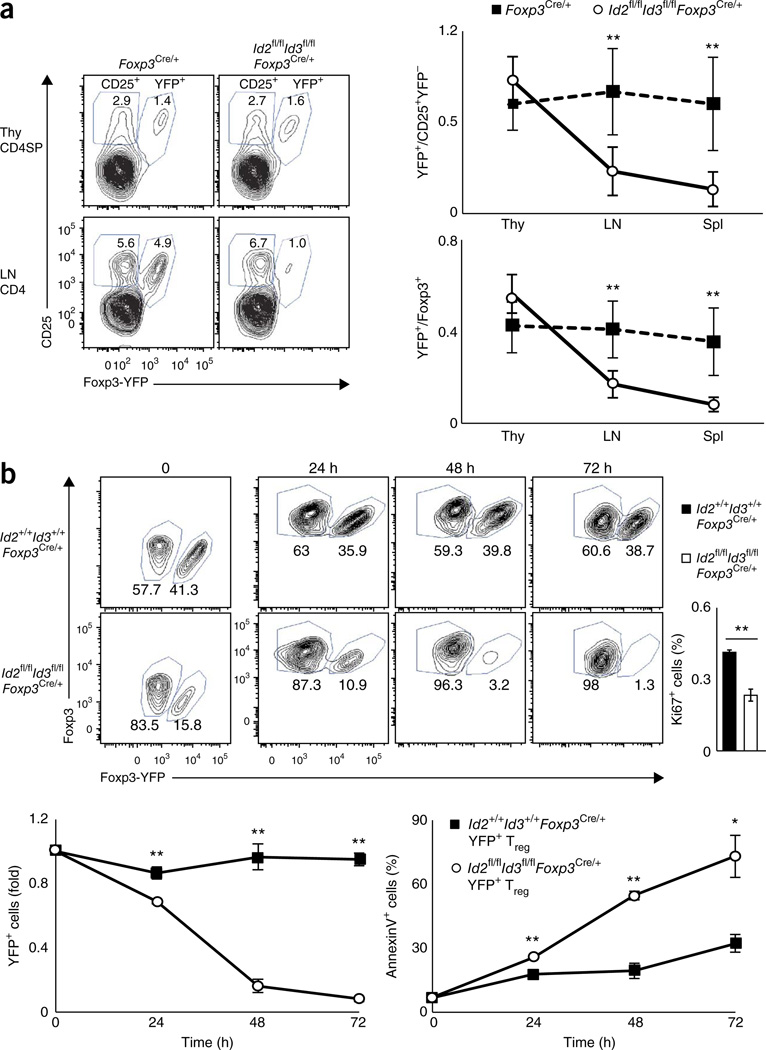

To assess directly the roles of Id2 and Id3 under noninflammatory conditions, we analyzed heterozygous female Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre/+ mice carrying the IRES-YFP reporter as described above. As inactivation of the X chromosome can occur on either allele, 50% of the Treg cells in heterozygous female Foxp3Cre-YFP/+ mice expressed the Foxp3Cre-YFP marker, whereas the rest of the Treg cell population lacked expression of Foxp3Cre-YFP. This setting allows for a direct functional comparison of Treg cells that are deficient for Id2 and Id3 expression versus wild-type cells under noninflammatory conditions. In the thymi derived from female Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre/+ mice, the YFP+/CD25+ ratio of the CD4+ T cell population was comparable to that of Id2+/+Id3+/+ Foxp3Cre/+ mice, whereas the YFP+/CD25+ ratio in the spleen and LNs was substantially reduced (Fig. 7a). Similarly, the fraction of YFP+ cells as compared to the proportion of Foxp3+ cells was substantially lower in spleen and LNs, indicating that the Id-sufficient Foxp3+ population outcompeted the Id-deficient population (Fig. 7a). We did not detect obvious differences in CD25, Annexin-V or Ki67 expression in Id2- and Id3-deficient YFP+ Treg cells derived from Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre/+ versus Foxp3Cre/+ mice (data not shown). Notably, we found that when cultured in the presence of anti-CD3 and anti-CD28, the fraction of Treg cells depleted for Id2 and Id3 expression (YFP+ cells) among Foxp3+ populations declined progressively over time and was accompanied by elevated numbers of apoptotic cells and decreased numbers of Ki67+ cells at 24 h (Fig. 7b). These observations indicate that in the absence of Id2 and Id3, Treg cells are more susceptible to cell death upon TCR stimulation. Collectively, these data indicate that Id2 and Id3 expression is required to maintain the peripheral Treg cell pool.

Figure 7.

Id2 and Id3 modulate the homeostasis and survival of Treg cells. (a) Flow cytometric analysis for YFP and CD25 expression on cells isolated from thymocytes (Thy) and LNs (LN) derived from Id2+/+Id3+/+Foxp3Cre/+ or Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre/+ mice (left; cells were gated on the CD4+CD8−TCRβhi, CD4+CD8− or CD4+ populations). Numbers in plots indicate percent YFP+CD25+ and YFP−CD25+ cells. Ratios of YFP+ Treg cells versus CD25+YFP−Treg cells and YFP+Foxp3+ Treg versus Foxp3+ Treg cells in indicated tissues (right). (b) Flow cytometric analysis of the Foxp3+CD4+ population in splenocytes derived from heterozygous female Id2+/+Id3+/+Foxp3Cre/+ or Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre/+ mice cultured and stimulated with anti-CD3ε plus anti-CD28 antibodies in the presence of human IL-2 (top left). Numbers indicate the fraction of YFP+Foxp3+ and YFP−Foxp3+ cells. Percentages of Ki67+ cells in the YFP+ Treg cell populations analyzed 24 h after stimulation for the indicated genotypes (top right). Ratios of YFP+ cells for the indicated time points as compared to the zero time point (bottom left). Percentages of annexin-V+ cells gated on the YFP+ Treg cell population (right). Data are representative of three independent experiments (a; mean ± s.d.; Id2+/+Id3+/+Foxp3cre/+n = 5, Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3cre/+n = 7 biological replicates) and one experiment (b; mean ± s.d.; n = 3 technical replicates). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test).

Id2 and Id3 regulate TFR cell–specific transcription signatures

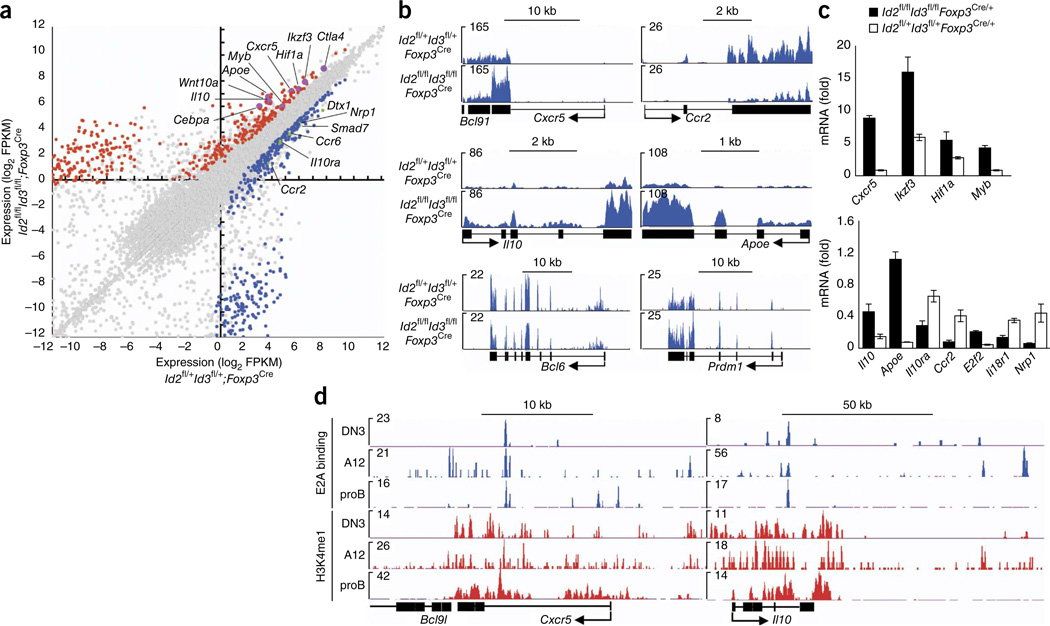

As a first approach to identify critical target genes affected by the depletion of Id2 and Id3 in Treg cells, we isolated by cell sorting YFP+ Treg cells from subcutaneous LNs derived from 3-week-old Id2fl/flId3fl/fl Foxp3Cre or Id2fl/+Id3fl/+Foxp3Cre mice. 792 genes were differentially expressed (greater than twofold; fragments per kilobase of exons per million fragments mapped; FPKM) in YFP+ Treg cells derived from Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre mice when compared to those in Id2fl/+Id3fl/+Foxp3Cre mice (Fig. 8a). Hierarchical clustering showed that a large fraction of transcripts that were differentially expressed were associated with genes encoding for metabolic process, transcription, T cell lymphocyte activation, cytokine/chemokine inflammation, cell cycle and cell death by Gene Ontology (GO) analysis (Supplementary Fig. 9). Prominent among the putative targets were Cxcr5, Ikzf3, Cebpa, Hif1a, Pparg, Il10, Il10ra, Ccr2, Nrp1 and Ccr6 (Fig. 8a–c and Supplementary Fig. 10a). However, expression of genes encoding transcriptional regulators, such as Tbx21, Irf4, Gata3, Stat3, Prdm1 and Sh2d1a, was not affected (data not shown). Similarly, cytokine genes including Il2, Il4, Il5, Il13, Ifng, Il17 and Il21 were not modulated upon depletion of Id2 and Id3 expression in the Treg cell pool (data not shown). Similar to the case in TFR cells, we found elevated expression of Gzma, Il10 and Ctla4. On the other hand, expression of Bcl6 and Prdm1 was not altered15 (Fig. 8a,b and Supplementary Fig. 10a).

Figure 8.

Unique patterns of gene expression in Treg cells depleted for Id2 and Id3. (a) RNA-seq analysis of mRNA expression in sorted Treg cells isolated from Id2fl/+Id3fl/+Foxp3Cre versus Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre mice (log2; FPKM values for RefSeq genes). Points represent genes upregulated in Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre Treg cells > twofold (red; P < 0.05 (calculated by Cuffdiff)), genes downregulated in Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre Treg cells > twofold (blue; P < 0.05) and not significantly changed (gray) as compared to control cells. Selected genes are labeled. (b) RNA-seq analysis at Cxcr5, Ccr2, Il10, Apoe, Bcl6 and Prdm1 loci, presented in reads per million reads aligned (RPM). Arrows indicate transcription start site and direction of transcription. (c) Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of genes in sorted Foxp3-YFP+ Treg cells derived from LNs isolated from heterozygous female Id2+/+Id3+/+Foxp3Cre/+ or Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre/+ mice, presented normalized by the abundance of Hprt1 transcript. (d) E2A occupancy (E2A binding) and deposition of H3K4me1 across the Cxcr5 and Il10 loci in DN3, A12 and proB cells. Numbers in plots indicate total tags observed. DN3 cells; Rag2−/− thymocytes, A12 cells; E2a/ E47-reconstituted T cell line, pro-B cells; Rag2−/− bone marrow B cells. Arrows indicate transcriptional start site and direction of transcription. Data are representative of three experiments (a,b), one experiment (c; mean ± s.d.; n = 3 technical replicates) and one experiment (d).

To identify target genes directly affected by depletion of Id2 and Id3 expression rather than genes affected by inflammatory disease, we isolated RNA from YFP+ Treg cells from heterozygous female Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre/+ and Id2+/+Id3+/+Foxp3Cre/+ mice and examined it by real-time PCR. We found that ablation of Id2 and Id3 expression in the Treg cell pool in healthy mice affected Cxcr5, Ikzf3, Hif1a, Myb, Apoe, Il10, Il10ra, Ccr2, E2f2, Nrp1 and Il18r1 transcript abundance (Fig. 8c). In contrast, Ikzf4, Ccr6, Cebpa, Pparg1 and S1pr1 transcript abundance was not altered in Treg cells depleted of Id2 and Id3 (data not shown). To determine whether the differences in transcript abundance directly relate to transcription factor occupancy across putative enhancer elements, we inspected previous genome-wide studies for E2A occupancy as well as deposition of monomethylation of histone H3K4 (H3K4me1) in CD4−CD8−double-negative (DN3) thymocytes, pro-B cells and T cell lymphomas26,40. Notably, E2A-bound sites were closely associated with putative enhancer regions across the Cxcr5, IL10, Hif1a, Ikzf3, Myb, Il10ra, Nrp1, E2f2 and Bmp7 loci, which indicated that this ensemble of loci is directly regulated by E proteins (Fig. 8d and Supplementary Fig. 10b). These data indicate that a subset of genes associated with TFR cells, including Il10 and Cxcr5, but not Bcl6 and Prdm1, are directly regulated by the expression of Id2 and Id3 in Treg cells to orchestrate the developmental progression of the TFR cell population (Supplementary Fig. 10c).

DISCUSSION

Here we demonstrated that expression of the antagonist HLH proteins, Id2 and Id3, in Treg cells is required for suppression of early onset inflammation at mucosal barriers. How does depletion of Id2 and Id3 expression in Treg cells lead to the development of severe inflammation? Our data indicate that expression of Id2 and Id3 is essential to maintain the Treg cell population. In 3– 4-week-old mice that lacked expression of Id2 and Id3, we observed Treg cells in near wild-type numbers. However, in 7–8-week-old mice, the Treg cell population depleted for expression of Id2 and Id3 was severely reduced across the lung tissues. Homing of Treg cells to the lung in transfer experiments was also compromised in the absence of Id2 and Id3 expression. Finally, we found that activated Treg cells depleted for expression of Id2 and Id3 displayed decreased viability and impaired proliferation upon stimulation. Collectively, these data indicate that Id2 and Id3 coordinate the survival, expansion and homing of Treg cells under inflammatory conditions.

In addition to the roles of Id2 and Id3 in suppressing TH2 cell– mediated inflammation, our observations also point to a role for Id2 and Id3 in TFR cell development. How may Id2 and Id3 regulate TFR differentiation? We suggest that Id2 and Id3 expression enforces distinct TFR checkpoints. Upon TCR-mediated signaling, Id2 and Id3 levels readily decline permitting increased E-protein binding activity and the induction of a TFR-specific transcription signature, including the activation of Cxcr5 and IL-10 expression. We propose that abundance of Id2 and/or Id3 is elevated and required again in differentiating TFR cells to indirectly modulate Bcl-6 and Blimp-1 protein abundance, which ultimately leads to the development of a mature TFR cell population.

There are interesting parallels between the roles of E and Id proteins in development of TFR cells and TFH cells. Differentiation of TFH cells is characterized by distinct developmental stages. First, upon activation, effector TFH cells induce the expression of CXCR5 to migrate to the border that separates the T cell areas from the B cell follicles. Followed by ICOS-ICOSL interaction with B cells, TFH cells continue to differentiate, acquire Bcl-6 expression and migrate to GCs41,42. Two critical factors control the early developmental progression of naive CD4+ T cells toward the effector TFH cell type: Id3 and a heterodimeric complex involving the basic HLH protein Ascl2 and E proteins to activate the expression of CXCR5 and other critical target genes26,43,44. Based on these observations, we suggest that a common genetic circuitry that involves the E-Id protein module controls the homing of both TFR cells and TFH cells.

In sum, higher Id2 and Id3 expression enforces the early TFR cell checkpoint, whereas at intermediate developmental stages the abundance of E protein versus Id protein controls developmental progression toward a fully mature TFR cell fate. We note this property of Id proteins and E proteins is not unique to Treg cells. Previous studies have demonstrated critical roles for E and Id proteins acting as gatekeepers at the pre-TCR, TCR and B cell antigen receptor checkpoints21,23,45–47. During the developmental progression of the CD8+ and TFH cell lineages, the Id proteins also control key developmental transitions27,48,49. Each of these checkpoints involves the regulation of Id protein expression by antigen receptor–mediated signaling. Thus, a picture is now emerging in which antigen receptors directly connect to the E protein and Id protein machinery to orchestrate the developmental transitions of cells that comprise the adaptive immune system under healthy as well as inflammatory conditions.

ONLINE METHODS

Mice

C57BL/6, Id3fl/fl, Id2fl/fl Id3−/−, Foxp3 Cre-YFP and Id3GFP/+ Id2YFP/+ mice were bred and housed in specific pathogen-free conditions in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Guidelines of the University of California, San Diego.

Flow cytometry

Single-cell suspensions from thymus, lymph nodes and spleen were stained with the following: FITC-, PE-, APC-, APC-Cy7-, Pacific Blue-, Alexa Fluor 700-, Alexa Fluor 780-, PerCP-Cy5.5-, PE-Cy7- or biotin-labeled monoclonal antibodies were purchased from BD PharMingen including CD11c (HL3), CD44 (IM7), CXCR5 (2G8), CD95 (Jo-2), GL-7 (GL7), SiglecF (E50–2440), IL-5 (TRFK5). CD8 (53-6.7), CD19 (ID3), CD38 (90), CD62L (MEL-14), CD44 (IM7), B220 (RA3–6B2), Mac1 (M1/70), Gr1 (RB6–8C5), Nk1.1 (PK136), Ter119 (TER119), TCRβ (H57), TCRγδ (GL3), PD-1 (J43), ICOS (7E.17G9), CXCR4 (2B11), IL-4 (11B11), IL-13 (eBio13A), IL-17 (eBio17B7), IFN-γ(XMG1.2), FOXP3 (FJK-16s) and TBR2 (Dan11mag) were purchased from eBioscience. FceR1 (MAR-1), CD3e (2C11), CD4 (GK1.5), CD8 (53-6.7), CD11b (M1/70), CD25 (PC61), CD122 (TMb1), CTLA4 (UC10-4B9), CCR6 (29-2L17), Helios (22F6) and PD-1 (RMP1–30) were obtained from BioLegend. Anti-Nrp1 (AF566) was purchased from R&D Systems. Biotinylated antibodies were labeled with streptavidin-conjugated Qdot-665 or Qdot-605 (Invitrogen). Clone 2.4 G2 anti-CD32:CD16 (eBioscience) was used to block Fc receptors. Dead cells were removed from analysis and sorting by staining with propidium iodide (PI) (Sigma-Aldrich). Isolation of lung single cells was performed as described51. Mouse Treg cell staining kit (eBioscience) was used for intracellular Foxp3, CTLA4 and Helios staining. Samples were collected on a LSRII (BD Biosciences) and were analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star). Cells were sorted on a FACSAria (BD). For intracellular staining of IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-5, IL-13 and IL-17, isolated cells from spleen and lymph nodes were treated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) plus ionomycin (4 h) and Golgi stop (2 h). After culture, cells were stained with anti-CD4, CD8, TCRβ and CD3e. Intracellular staining was performed with the BD Biosciences Cytofix/Cytopermkit.

RNA sequencing

Total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy-Mini Kit (Qiagen) and was processed for deep sequencing as described previously with slight modifications. Briefly, mRNA was purified from total RNA using Dynabeads mRNA purification kit (Invitrogen). The mRNA was then subjected to first-strand cDNA synthesis using a combination of random hexamers and oligo(dT). Second-strand synthesis was performed using dUTP instead of dTTP. The double-stranded cDNA was sonicated using S220 Focused-ultrasonicator (Covaris). Sonicated cDNA was next ligated to adaptors and size-selected. The size-selected cDNA was treated with uracil-N-glycosylase and then multiplex-amplified by PCR. cDNA libraries were sequenced with a HiSeq 2000 sequencer (Illumina). Sequence reads from each cDNA library were analyzed with Galaxy (http://galaxyproject.org/). They were mapped to mouse genome build NCBI37 mm9 using TopHat. The expression values were obtained using Cufflink and Cuffdiff. GO analyses were performed using Homer (http://homer.salk.edu/homer/index.html). Visualization files were generated using Homer and read pile-ups visualized using the University of California Santa Cruz Genome Browser.

Histology and immunostaining

Tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences). Fixed tissues were embedded in paraffin and sliced, followed by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, periodic acid Schiff (PAS) staining and MBP staining. For MBP immunostaining, we used a monoclonal antibody directed against MBP51. For quantification of MBP+ or PAS+ cells, we chose five bronchioles and count positive cells in one mouse. For Foxp3 staining, spleen and lymph nodes were embedded in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound and snap-frozen. 5-µm serial sections were stained with anti-CD45R (B220; supernatant isolated from the medium of cultured hybridomas) or anti-Foxp3 (FJK-16s). Secondary antibody used was donkey anti-rat IgG Alexa Fluor 488 (Molecular Probes). The images were captured by Olympus Provis AX80 microscopy. The digital images were acquired using RETIGA EXi (Nippon Rooper). Image process was done by Photoshop (Adobe). IBD scores were calculated as described50.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Serum IgM, IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, IgG3 and IgA were done as described52. For IgE, ELISA was performed using Mouse IgE Standard Set Module (BioLegend).

RNA isolation and reverse transcriptase PCR

First, cDNA was obtained from purified YFP+ or CD25+ Treg cells from Id2+/+Id3+/+Foxp3Cre/+ or Id2fl/flId3fl/flFoxp3Cre/+ mice. Total RNA was isolated from sorted cells with RNeasy kit (Quagen), followed by reverse transcription with the SuperScript III RT-PCR system (Invitrogen) and quantitative real-time reverse transcription (RT)-PCR.

In vitro and in vivo suppression and in vitro stimulation

For in vitro suppression assay, YFP+ Treg cells and responder CD4+CD25− T cells were purified by sorting. 2 × 104 Responder CD4+ T cells were cocultured with Treg cells at indicated ratios and were stimulated with soluble anti-CD3 antibody (1 µg/ml) in the presence of T cell–depleted splenocytes treated with mitomycin C (1 × 105) in 96-well plates for 72 h. Cells were pulsed with [3H]thymidine deoxyribose (1 µCi/well) for the last 12 h. In vivo suppression assay was performed as described53. For in vitro stimulation, total lymphocytes were cultured in vitro and stimulated with anti-CD3ε (0.5 µg/ml) plus anti-CD28 (1 µg/ml) antibodies in the presence of human IL-2 (100 U/ml) as described30.

Statistical analysis

P values were calculated with the two-tailed Student’s t-test for two-group comparison as applicable with Microsoft Excel software. The statistical significance level was 0.05.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank A. Bortnick for critical reading of the manuscript, S. Kuan, B. Lin and Z. Ye for help with Illumina DNA sequencing, B. Ren for access to the Illumina Hi-Seq instrumentation, A. Goldrath (University of California San Diego) for Id2-YFP mice, Y. Zhuang for Id3fl/fl mice (Duke University), A. Lasorella (Columbia University) for Id2fl/fl mice, Y. Zheng (Salk Institute) for Foxp3-deficient organs, C. Katayama, M. Suzukawa, L. Deng, P. Rosenthal, T. Katakai, A. Beppu and A. Coddington for technical advice, J. Lee (Mayo Clinic) for providing the MBP antibodies, and members of the University of California, San Diego Histology Core for performing histology. This work was supported by US National Institutes of Health (AI 38425, AI 70535 and AI 7211 to D.H.B. and CA054198, CA78384 and 1P01AI102853 to C.M.).

Footnotes

Accession codes. Gene Expression Ominibus: GSE57682.

Note: Any Supplementary Information and Source Data files are available in the online version of the paper.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.Miy., K.M. and S.C. performed the majority of experiments. K.M. performed RNA-seq analysis. M.I. performed immunostaining of spleen and lymph nodes. N.V. contributed to the analysis of pathology. M.Mil. contributed to the analysis of lung tissue. L.-F.L. suggested key experiments and edited the manuscript. A.N.C. analyzed RNA-seq data. M.Miy. and C.M. wrote the manuscript. D.H.B. and C.M. supervised the study.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Josefowicz SZ, Lu LF, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cells: mechanisms of differentiation and function. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2012;30:531–564. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sakaguchi S, Yamaguchi T, Nomura T, Ono M. Regulatory T cells and immune tolerance. Cell. 2008;133:775–787. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vignali DAA, Collison LW, Workman CJ. How regulatory T cells work. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008;8:523–532. doi: 10.1038/nri2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Locksley RM. Asthma and allergic inflammation. Cell. 2010;140:777–783. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rothenberg ME, Hogan SP. The eosinophil. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2006;24:147–174. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sakaguchi S, et al. Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by activated T cells expressing Il2-receptor alpha-chains (CD25). Breakdown of a single mechanism of self-tolerance causes various autoimmune diseases. J. Immunol. 1995;155:1151–1164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bennett CL, et al. The immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopahty, X-linked syndrome (IPEX) is caused by mutations of Foxp3. Nat. Genet. 2001;27:20–21. doi: 10.1038/83713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wildin RS, et al. X-linked neonatal diabetes, emteropathy and endocrinopathy syndrome is the human equivalent of mouse scurfy. Nat. Genet. 2001;27:18–20. doi: 10.1038/83707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hori S, Nomura T, Sakaguchi S. Control of regulatory T cell development by the transcription factor Foxp3. Science. 2003;299:1057–1061. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fontenot JD, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. Foxp3 programs the development and function of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2003;4:330–336. doi: 10.1038/ni904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khattri R, Cox T, Yasayko SA, Ramsdell F. An essential role for Scurfin in CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells. Nat. Immunol. 2003;4:337–342. doi: 10.1038/ni909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Josefowicz SZ, et al. Extratymically generated regulatory T cells control mucosal Th2 inflammation. Nature. 2012;482:395–399. doi: 10.1038/nature10772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wing JB, Sakaguchi S. Foxp3+ Treg cells in humoral immunity. Int. Immunol. 2014;26:61–69. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxt060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chung Y, et al. Follicular regulatory T cells expressing Foxp3 and Bcl-6 suppress germinal center reactions. Nat. Med. 2011;17:983–988. doi: 10.1038/nm.2426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Linterman MA, et al. Foxp3 follicular regulatory T cells control the germinal center response. Nat. Med. 2011;17:975–982. doi: 10.1038/nm.2425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sage PT, Francisco LM, Carman CV, Sharpe AH. The receptor PD-1 controls follicular regulatory T cells in the lymph nodes and blood. Nat. Immunol. 2013;14:152–161. doi: 10.1038/ni.2496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murre C. Helix-loop-helix proteins and lymphocyte development. Nat. Immunol. 2005;6:1079–1086. doi: 10.1038/ni1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murre C, McCaw PS, Baltimore D. A new DNA binding and dimerization motif. Cell. 1989;56:777–783. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90682-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benezra R, Davis RL, Lockshon D, Turner DL, Weintraub H. The protein Id: A negative regulator of helix-loop-helix DNA binding proteins. Cell. 1990;61:49–59. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90214-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yokota Y, et al. Development of peripheral lymphoid organs and natural killer cells depends on the helix-loop-helix protein Id2. Nature. 1999;397:702–706. doi: 10.1038/17812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rivera RR, Johns CP, Quan J, Johnson RS, Murre C. Thymocyte selection is regulated by the helix-loop-helix inhibitor protein, Id3. Immunity. 2000;12:17–26. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80155-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Verykokakis M, Boos MD, Bendelac A, Kee BL. SAP protein-dependent natural killer T-like cells regulate the development of CD8(+) T cells with innate lymphocyte characteristics. Immunity. 2010;33:203–215. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones-Mason ME, et al. E protein transcription factors are required for the development of CD4(+) lineage T cells. Immunity. 2012;36:348–361. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li H, Dai M, Zhuang YA. T cell intrinsic role of Id3 in a mouse model for primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Immunity. 2004;21:551–560. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maruyama T, et al. Control of the differentiation of regulatory T cells and TH17 cells by the DNA-binding inhibitor Id3. Nat. Immunol. 2011;12:86–95. doi: 10.1038/ni.1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miyazaki M, et al. The opposing roles of the transcription factor E2A and its antagonist Id3 that orchestrate and enforce the naive fate of T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2011;12:992–1001. doi: 10.1038/ni.2086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang CY, et al. The transcriptional regulators Id2 and Id3 control the formation of distinct memory CD8+ T cell subsets. Nat. Immunol. 2011;12:1221–1229. doi: 10.1038/ni.2158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Niola F, et al. Id proteins synchronize stemness and anchorage to the niche of neural stem cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012;14:477–487. doi: 10.1038/ncb2490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rubtsov YP, et al. Regulatory T cell-derived interleukin-10 limits inflammation at environmental interfaces. Immunity. 2008;28:546–558. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liston A, Lu LF, O’Carroll D, Tarakhovsky A, Rudensky AY. Dicer-dependent microRNA pathway safeguards regulatory T cell function. J. Exp. Med. 2008;205:1993–2004. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nussbaum JC, et al. Type 2 Innate lymphoid cells control eosinophil homeostasis. Nature. 2013;502:245–248. doi: 10.1038/nature12526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Monticelli LA, Sonnenberg GF, Artis D. Innate lymphoid cells: critical regulators of allergic inflammation and tissue repair in the lung. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2012;24:284–289. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2012.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang YJ, et al. Innate lymphoid cells mediate influenza-induced airway hyper-reactivity independently of adaptive immunity. Nat. Immunol. 2011;12:631–638. doi: 10.1038/ni.2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cretney E, Kallies A, Nutt SL. Differentiation and function of Foxp3+ effector regulatory T cells. Trends Immunol. 2013;34:74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cretney E, et al. The transcription factors, Blimp-1 and IRF4 jointly control the differentiation and function of effector regulatory T cells. Nat. Immunol. 2011;12:304–311. doi: 10.1038/ni.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smigiel KS, et al. CCR7 provides localized access to IL-2 and defines homeostatically distinct regulatory T cell subsets. J. Exp. Med. 2014;211:121–136. doi: 10.1084/jem.20131142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thornton AM, et al. Expression of Helios, an Ikaros transcription factor family member, differentiates thymic-derived from peripherally induced Foxp3+ T regulatory cells. J. Immunol. 2010;184:3433–3441. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0904028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weiss JM, et al. Neuropilin 1 is expressed on thymus-derived natural regulatory T cells, but not mucosa-generated induced Foxp3+ Treg cells. J. Exp. Med. 2012;209:1723–1742. doi: 10.1084/jem.20120914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Delgoffe GM, et al. Stability of regulatory T cells is maintained by a neuropilin-1-semaphorin-4a axis. Nature. 2013;501:252–256. doi: 10.1038/nature12428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin YC, et al. A global network of transcription factors, involving E2A, EBF1, and Foxo1, that orchestrates B cell fate. Nat. Immunol. 2010;11:635–643. doi: 10.1038/ni.1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu H, et al. Follicular T-helper cell recruitment governed by bystanding B cells and ICOS-driven motility. Nature. 2013;496:523–527. doi: 10.1038/nature12058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Choi YS, et al. ICOS receptor instructs T follicular helper cell versus effector cell differentiation via induction of the transcriptional repressor Bcl6. Immunity. 2011;34:932–946. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu X, et al. Transcription factor achaete-scute homologue 2 initiates follicular T-helper-cell development. Nature. 2014;507:513–518. doi: 10.1038/nature12910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Murre C, et al. Interactions between heterologous helix-loop-helix proteins generate complexes that bind specifically to a common DNA sequence. Cell. 1989;58:537–544. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90434-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bain G, et al. Thymocyte maturation is regulated by the activity of the helix-loop-helix protein, E47. J. Exp. Med. 1999;190:1605–1616. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.11.1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Engel I, Johns C, Bain G, Rivera RR, Murre C. Early thymocyte development is regulated by modulation of E2A protein activity. J. Exp. Med. 2001;194:733–745. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.6.733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Quong M, et al. Receptor editing and marginal zone B cell development are regulated by the helix-loop-helix protein, E2A. J. Exp. Med. 2004;199:1101–1112. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Masson F, et al. Id2-mediated inhibition of E2A represses memory CD8+ T cell differentiation. J. Immunol. 2013;190:4585–4594. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Knell J, et al. Id2 influences differentiation of killer cell lectin-like receptor G1(hi) short-lived CD8+ effector T cells. J. Immunol. 2013;190:1501–1509. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Burich A, et al. Helicobacter-induced inflammatory bowel disease in IL-10- and T cell-deficient mice. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2001;281:G764–G778. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.281.3.G764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Suzukawa M, et al. Sialyltransferase ST3Gal-III regulates SiglecF ligand formation and eosinophilic lung inflammation in mice. J. Immunol. 2013;190:5939–5948. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith KGC, et al. bcl-2 transgene expression Inhibits apoptosis in the germinal center and reveals differences in the selection of memory B cells and bone marrow antibody-forming cells. J. Exp. Med. 2000;191:475–484. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.3.475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miyazaki K, et al. The role of the basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor Dec1 in the regulatory T cells. J. Immunol. 2010;185:7330–7339. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.