Abstract

Accumulation of amyloid β (Aβ) is a major hallmark in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Bone marrow derived monocytic cells (BMM) have been shown to reduce Aβ burden in mouse models of AD, alleviating the AD pathology. BMM have been shown to be more efficient phagocytes in AD than the endogenous brain microglia. Because BMM have a natural tendency to infiltrate into the injured area, they could be regarded as optimal candidates for cell-based therapy in AD. In this study, we describe a method to obtain monocytic cells from BM-derived haematopoietic stem cells (HSC). Mouse or human HSC were isolated and differentiated in the presence of macrophage colony stimulating factor (MCSF). The cells were characterized by assessing the expression profile of monocyte markers and cytokine response to inflammatory stimulus. The phagocytic capacity was determined with Aβ uptake assay in vitro and Aβ degradation assay of natively formed Aβ deposits ex vivo and in a transgenic APdE9 mouse model of AD in vivo. HSC were lentivirally transduced with enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) to determine the effect of gene modification on the potential of HSC-derived cells for therapeutic purposes. HSC-derived monocytic cells (HSCM) displayed inflammatory responses comparable to microglia and peripheral monocytes. We also show that HSCM contributed to Aβ reduction and could be genetically modified without compromising their function. These monocytic cells could be obtained from human BM or mobilized peripheral blood HSC, indicating a potential therapeutic relevance for AD.

Keywords: monocytes, haematopoietic stem cells, β-amyloid, Alzheimer’s disease, inflammation, phagocytosis, viral transduction

Introduction

The major hallmarks of AD include Aβ deposits and neurofibrillary tangles, accumulating in the brain regions that serve cognition and memory [1]. They are formed by aggregated Aβ peptides and hyperphosphorylated τ protein, respectively. In the amyloidogenic pathway, amyloid precursor protein is cleaved into Aβ peptides Aβ40 and Aβ42, the latter being more prone to aggregation [1-3]. Monomeric Aβ spontaneously aggregates into oligomers and high-molecular weight oligomers, which further aggregate to form insoluble fibrils and Aβ plaques [1]. Aβ-mediated destruction of neuronal integrity is dependent on Aβ aggregation state from which Aβ oligomers are the most neurotoxic [2, 3]. In addition, Aβ signaling in non-neuronal cells and Aβ removal by astrocytes and brain mononuclear phagocytes, including microglia, are also dependent on the Aβ aggregation state [4-7].

The imbalance between Aβ production and clearance is thought to be an initiating factor in AD. Although the clearance mechanisms of excess Aβ are diverse, even a small chronic defect in Aβ clearance may be sufficient to cause AD [2]. There are numerous proteolytic enzymes such as neprilysin, insulin-degrading enzyme and matrix metalloproteases all which degrade Aβ and have been shown to regulate Aβ deposition in mouse models of AD [2]. Brain glial cells, both astrocytes [4,8–10] and microglia [5,6,11–13] have been shown to contribute to Aβ clearance and play a significant role in the control of AD pathogenesis. However, the progressive Aβ accumulation in spite of increased microglia activation and recruitment within the Aβ plaques suggests that the ability of microglia to clear Aβ decreases with age and the progression of AD [14].

How the renewal of brain mononuclear phagocytes occurs has not yet been unanimously interpreted [15,16]. Nevertheless, in addition to self-renewal of brain endogenous microglia, there are populations of peripheral monocytic cells capable of crossing the blood–brain barrier (BBB) and infiltrating into the brain parenchyma [17-24]. Peripheral monocytic cells have also been shown to infiltrate into the brain parenchyma or perivascular area in AD. They associate with Aβ deposits and aid in Aβ clearance by hampering the accumulation of Aβ or reducing pre-formed Aβ deposits [25-28]. It has been shown that a chemokine C-C receptor 2 (CCR2), a receptor for CCL2-mediated leucocyte chemotaxis, is required for early microglia accumulation and delay of the disease progression in AD [29]. Early microglia accumulation in AD before formation of senile plaques involves the recruitment of peripheral monocytic cells [25, 26] and it was previously demonstrated that microglia indeed rise from CCR2+Ly6Chigh monocytes [30].

However, the recruitment of CCR2+Ly6Chigh monocytes may only occur under defined host conditions [30], suggesting that monocyte access into the brain parenchyma in sufficient quantity may require pre-conditioning of the cells and/or of the BBB integrity. A recent study demonstrated that peripherally transplanted CD11b+ BMM migrate into the vicinity of Aβ plaques and that these cells can be utilized as gene delivery vehicles carrying and secreting the proteolytic enzyme neprilysin to substantially reduce Aβ burden in AD [31].

Monocytes originate from BM HSC, reside in BM or spleen as myeloid or monocyte progenitors of various differentiation stages and properties, and are eventually released into the blood on demand [32-34]. In peripheral blood (PB) they exist as two main subsets; inflammatory CCR2+Ly6C+/highCD115+ and resident CCR2−Ly6C−/lowCD115+ monocytes, with CCR2+CD14highCD16− and CCR2−CD14+CD16+ as their human counterparts. These subsets of monocytes have different migration properties and function in inflammatory and steady-state conditions. After their exit from blood, monocytes differentiate into tissue-specific macrophages and dendritic cells. Macrophages, including microglia in the brain represent a spectrum of inflammatory cells ranging from so-called classically to alternatively activated macrophages [33]. It has been demonstrated that inflammatory Ly6C+ monocytes may be recruited into the inflamed or injured area instantly and display classical activation with secretion of inflammatory cytokines and phagocytic activity whereas Ly6C− may be recruited later when alternative activation with wound repair, tissue remodelling and immunomodulation would be required [33].

Because monocytes have been demonstrated (i) to regulate the progression of AD, (ii) to migrate into the damaged areas in AD and (iii) as phagocytic and immunomodulatory cells to alleviate the AD pathology, they appear optimal candidates for cell-mediated therapy in AD. However, because monocytes are short-lived cells, limited in number, and transfection and viral transduction has proven to be difficult [35], there is certainly a need for an infinite pool of monocytic cells originating from stem cells. We have differentiated BM HSC into monocytic lineage cells [27] and herein, we characterize them for possible therapeutic purposes in AD. We demonstrate that long-term HSC can be expanded and differentiated in vitro into monocytic cells with inflammatory responses comparable to peripheral monocytes and microglia. We also show that HSC-derived monocytic cells (HSCM) contribute to Aβ reduction and can be genetically modified without compromising their function. Therefore, these monocytic cells could be obtained from human BM and mobilized PB HSC, and potentially be used for AD cell-based therapy.

Materials and methods

BM cell culture

BM was isolated from 5- to 8-week-old C57BL mice. For HSC mobilization, adult mice were treated s.c. with a single dose of granulocyte colony stimulating factor (GCSF) 500 μg/kg (Pegfilgrastim, Neulasta, Amgen, diluted in sterile 0.15M sodium acetate, pH adjusted to 7.4. with acetic acid) 3–4 days before sacrifice. BM was isolated and cultivated as described earlier [26,27]. Briefly, mononuclear cells were isolated by gradient centrifugation and HSC were isolated by immunomagnetic cell separation using CD117 mouse HSC positive selection kit (EasySep, StemCell Technologies). CD117+ cells were plated at 100,000 cells/cm2 and proliferated in vitro in serum-free conditions as described [27]. The non-adherent cells were replated every 2 days when half of the medium was refreshed. For differentiation into monocytic lineage, non-adherent cells were collected and plated at 100,000 cells/cm2 in the presence of low endotoxin serum (Gibco) and 10 ng/ml MCSF (R&D Systems, Oxon, United Kingdom). After differentiation, the cells were collected in PBS. Adherent cells were detached gently with repeated pipetting in PBS.

Human BM was received from Kuopio University Hospital, as approved by the Board of Research Ethics, Hospital District of Northern Savo, Finland. The research was carried out according to the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki and informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Mononuclear cells were isolated by gradient centrifugation with Ficoll Paque (Amersham). HSC were isolated by immunomagnetic cell separation using human CD34+ selection kit (EasySep, StemCell Technologies). CD34+ cells were used fresh after the isolation or frozen in 10% DMSO, 90% FBS, in liquid nitrogen until use. CD34+ cells were plated at 100,000 cells/cm2 and proliferated in vitro in serum-free conditions [27], supplemented with haematopoietic cytokines (StemSpan Cytokine Cocktail; Stem Cell Technologies, Grenoble, France) including 100 ng/ml stem cell factor, 100 ng/ml Flt-3, 20 ng/ml IL-6, 20 ng/ml IL-3, in humidified atmosphere at 37°C in 5% CO2. Cells were cultivated and differentiated as described earlier. Human PB GCSF-mobilized CD34 cells were obtained from AllCells and cultivated similarly to BM-originated cells.

Mouse BMM were obtained as described [26] and isolated with mouse monocyte enrichment kit (EasySep, Stem Cell Technologies) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Microglia cell culture

Mouse neonatal microglia cultures were prepared as described earlier [36,37]. Microglia types I and II cells were collected as described [38].

Flow cytometry

Cells were counted and stained as described [26] with CCR2 (LifeSpan Technologies, Alpharetta, GA, USA), CD4 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA), CD40, CD49d, CD68, CD86, CD115 (all from Serotec, Oxford, UK), CD3e, CD11a, CD11b, CD11c, CD14, CD16, CD34, CD44, CD45, CD45R, MHCII, Ly6C, Ly6G (all from BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), CD117 and Sca-1 (StemCell Technologies) or isotype controls followed by secondary antibody stain (Alexa Fluor 488; Molecular Probes, Paisley, UK) when needed. A minimum of 10,000 events were acquired on FACSCalibur flow cytometer equipped with a 488 laser (BD) and data analysis was performed using Cellquest Pro software (BD).

Cytokine assay

Cells were treated with 10 ng/ml lipopolysaccharide (LPS; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 24 hrs. Media were collected and cytokine concentration determined with tumour necrosis factor-α (ELISA; R&D Systems). Detection of intracellular cytokine production was performed as described [39]. Briefly, cells were treated with 1 μg/ml LPS for 6 hrs including Brefeldin A (Sigma-Aldrich) for the last 4 hrs of incubation to inhibit protein transport and to enhance the detection of intracellular cytokines. Cells were collected and stained for cell surface markers (Ly6C or CD11b) as described earlier. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 20 min. at room temperature and then permeabilized with 0.05% saponin (Sigma-Aldrich). PE-conjugated TNF-α, IL-6 or IL-10 cytokine antibody or isotype control (all from eBioscience) was applied in PBS, 2% FBS, 0.05% saponin and incubated for 30 min. at RT. Cells were analysed on a flow cytometer as described earlier.

Nitric oxide assay

Cells were treated with 10 ng/ml LPS for 24 hrs in phenol red-free medium. Media were collected and mixed with an equal volume of Griess reagent (2% phosphoric acid, 1% sulfanilamide, 0.1% naphthylethylene dihydrochloride; Sigma-Aldrich), incubated for 10 min. and absorbance was measured at 540 nm with a multiscan reader. Sodium nitrite (Sigma-Aldrich) was used as a standard.

Aβ uptake assay

Aβ uptake assay was modified from Fiala et al. [40]. Cells were incubated with 2 μg/ml Aβ42 (HiLyte Fluor 488; AnaSpec, Fremont, CA, USA) for 24 hrs. Cells were fixed with 4% PFA and stained with CD68 (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) followed by Alexa Fluor 568 (Molecular Probes) staining. Labelling was visualized and observed with a fluorescent microscope (Olympus, Espoo, Finland). For quantification of Aβ uptake, cells were labelled with 0.5 μg/ml Aβ42 for 24 hrs and analysed on a flow cytometer as described earlier.

Ex vivo Aβ degradation assay

The ex vivo Aβ degradation assay was modified from Koistinaho et al. [8]. Brain sections were obtained from aged APdE9 mice [41] expressing human APP695 Swedish mutation and human PS1-dE9 (deletion in exon 9) vector as described [27]. Cells were applied onto the brain sections in differentiation medium. After the incubation, Aβ quantification was performed with Aβ ELISA and pan-Aβ immunostaining as described [27].

Lentiviral transduction

BM HSC were plated in serum-free medium as described earlier. For lentiviral gene transfer, eGFP-expressing lentivirus under the control of human phosphoglycerate kinase promoter was used. The lentivirus was produced and titrated as described [42]. The cells were incubated with the virus overnight (16 hrs) then diluted with a four-fold amount of fresh serum-free medium. Thereafter, the cells were cultivated as described earlier.

Cell viability was tested 1 day post-transduction with 1 μg/ml 7-aminoactino-mycin-D (7-AAD; Sigma-Aldrich). The transduction efficiency was determined after 3 days of cultivation by flow cytometer as described earlier.

Transplantation

BM transplantation to generate chimeric mice was performed as described [26]. Briefly, HSC were obtained from eGFP expressing C57BL mice [43] and cultivated as described earlier. The recipient mice were irradiated with medical linear accelerator (Varian Medical Systems) using 6 or 4 MV photon irradiation. The dose was delivered in two 550 cGy fractions with a 3-hr interval. The next day the mice were transplanted with 200,000 HSC in 200 μl of HBSS, 2% FBS by tail vein injection. The BM engraftment was determined after minimum of 4 weeks post-transplantation by saphenous vein blood collection. Cells were stained for lymphocyte, monocyte and granulocyte markers (CD3, CD45R, CD11b, Gr-1, all from BD) and analysed on a flow cytometer as described [26].

Intrahippocampal transplantation was performed as described [26]. Briefly, 2-year-old transgenic APdE9 mice [41] and their non-transgenic littermates were anaesthetized with isoflurane and placed in a stereotaxis apparatus. BM HSCM (300,000 in 1 μl of HBSS, 2% FBS) were injected with a Hamilton syringe into the right hippocampus and the same amount of vehicle was injected into the left hippocampus according to following coordinates: ±0.25 mm medial/lateral, −0.27 mm anterior/posterior, −0.25 mm dorsal/ventral from bregma. Four days post-transplantation, the brains were collected as described [26], immersion fixed with 4% PFA overnight, cryoprotected with 30% sucrose for 2 days, then snap frozen and stored at −70°C until processed for immunohistochemistry.

All animal experiments were conducted according to the national regulations for the use and welfare of laboratory animals and approved by the Animal Experiment Committee in State Provincial Office of Southern Finland.

Immunohistochemisty

Histological analysis was performed as described [26]. Briefly, 20 μm coronal sections were stained with pan-Aβ (Biosource, Paisley, UK), Iba-1 (Wako, Richmond, VA, USA), CD68 (Serotec) or GFAP (Dako) and followed by incubation with Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated secondary antibody. Staining was visualized with a fluorescent microscope and immunoreactive area was quantified using Image Pro Plus software (Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD, USA) from the hippocampal region. Confocal microscope (Zeiss, Tuusula, Finland) was used for co-localization analysis using ZEN software (Zeiss). The detailed information about antibodies used in this study can be found in Supplementary Data.

Statistical analysis

The data are expressed as mean ± S.D. and analysed with SPSS software using Student’s t-test or one-way anova when appropriate, followed by Dunnett’s or Tukey’s post-hoc test; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Results

BM HSC differentiate into monocytic cells in the presence of MCSF having a phenotype similar to BMM and partly distinct from microglia

To generate a pool of stem-cell derived monocytic cells, we isolated mouse CD117+ BM HSC and differentiated them into monocytic lineage. Human PB or BM cells are conventionally pre-purifed with a gradient centrifugation to isolate mononuclear leucocytes containing HSC. Similarly, we first pre-purified mouse BM mononuclear cells before proceeding to immunomagnetic isolation of CD117+ HSC. After the HSC purification, >90% of cells were CD117+. Because CD117 may be expressed, to a small extent, in some other cell types as well, we cultivated the CD117+ cells with haematopoietic cytokines in serum-free conditions as non-adherent cells to enhance the growth and proliferation of HSC. When we transplanted a lethally irradiated recipient mouse with 2 weeks in vitro proliferated eGFP-expressing HSC, the cells engrafted the mouse BM and this sustained as long as 1 year after the transplantation.

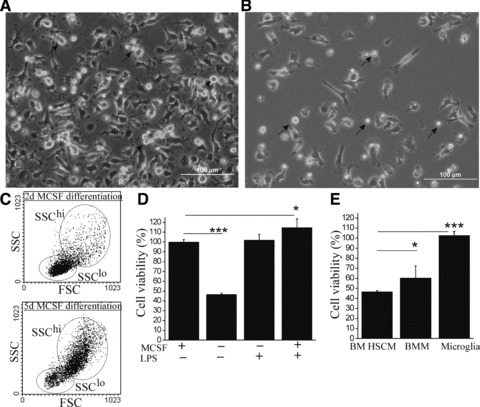

After proliferation, BM HSC were differentiated into monocytic cells in the presence of serum and MCSF. After 1–2 days of differentiation, the cells started gradually adhere forming sub-populations of non-adherent and adherent cells. After an extended period, that is 5 days of differentiation, the non-adherent cell population diminished while the majority of cells appeared adherent (Fig. 1A–C). Non-adherent cells appeared round and bright cells by light microscopy (Fig. 1A and B) and appeared in the low SSC area (SSClo) as analysed by flow cytometry (Fig. 1C). Adherent cells displayed higher SSC properties (SSChi) by flow cytometry (Fig. 1C) and resembled the morphology of more complex cells macrophages and microglia [44]. Microscopically, they appeared as long, rod shape cells; round or amorphous cells with short thick pseudopodic or thin lamellipodic processes; or flattened cells with a membraneous extension (Fig. 1A and B). Non-adherent SSClo HSCM had a higher cell proliferation rate as observed with cell count, cell viability assay based on metabolic activity as well as cell division marker CFSE (data not shown). We studied the properties of these two distinct populations of SSClo and SSChi HSCM in more detail.

Fig 1.

BM HSC differentiate into monocytic cells in the MCSF-dependent manner. Differentiating BM HSC formed sub-populations of monocytic cells with different adherence properties (A) shown after 5 days of MCSF differentiation. When plated in a lower cell concentration (B), the morphology of single cells could be better identified. Although non-adherent cells (depicted with arrows) were round, bright, small-sized cells, the adherent cells had distinct morphology. Non-adherent and adherent cells had also distinct SSC properties in flow cytometry (C). The proportion of non-adherent (SSClo) cells decreased within the time of MCSF differentiation (C). If the MCSF was omitted after the initial trigger of differentiation, cell growth was greatly reduced (D, P < 0.001, n = 6) as determined by cell viability assay measuring cell metabolism. The inflammatory stimulus with LPS (10 ng/ml), however, increased the cell growth to the level of MCSF (D, P < 0.001, n = 6). BM HSCM were more dependent on MCSF for their growth (E, n = 6–8) when compared to BMM and microglia. The results (E) are shown as cell viability in the absence of MCSF in comparison to parallel cultures in the presence of 10 ng/ml MCSF.

We determined the expression profile of BM HSCM in comparison to BMM and brain microglia. Similar to BMM, BM HSCM expressed integrins CD11a, CD11b and CD49d and cell adhesion molecule CD44 (Table 1), which are needed for monocyte migration as formerly reviewed [45]. In previous studies it has been shown that CD115, Ly6C and/or CCR2 expressing monocytes may migrate to the CNS during disease or injury [30,46]. Similar to BMM, we found BM HSCM to express CD115, Ly6C and CCR2. After prolonged MCSF differentiation, SSChi HSCM down-regulated their Ly6C expression and became firmly adherent cells suggesting that they decreased their property as differentiating monocytic cells and started to phenotypically resemble macrophages. Collectively, BM HSCM expressed CD68 similar to the other phagocytic cells, BMM and microglia but the expression was, however, up-regulated in the SSChi HSCM subset. Depending on their attachment property, there are two types of microglia that could be obtained from in vitro preparation of microglial cell culture [38]. These cells, called as microglia types I and II, obtained by shaking and mild trypsinization methods, respectively, display partly distinct properties and function [47]. Because microglia types I and II differences are not well known, we also included these cell types in our studies. Microglia types I and II differed from BM HSCM and BMM by having lower expression of integrins and no expression of CD115 and Ly6C which probably reflects them being more mature, resident cells. These results suggest that MCSF-differentiated BM HSCM resemble the migratory monocytes and have partly distinct phenotype from microglia.

Table 1.

Phenotype of BM HSCM in comparison to BMM and microglia

| Antigen | BM HSCM SSClo/SSChi2d | BM HSCM SSClo/SSChi5d | BMM | Brain MG I | Brain MG II |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD11a | +/+ | +/+ | ++ | 6 | 6 |

| CD11b | +/+ | +/+ | + | + | + |

| CD44 | ++/++ | ++/++ | ++ | + | – |

| CD49d | +/++ | +/++ | + | + | 6 |

| CD68 | +/++ | +/++ | + | + | + |

| CD115 | +/++ | +/++ | + | – | – |

| Ly6C | ++/+ | ++/– | ++ | – | – |

| CCR2 | ±/+ | 6/+ | 6 | + | + |

Phenotype of 2 and 5 days MCSF-differentiated mouse BM HSCM in comparison to BMM and brain microglia. Expression levels of monocyte markers are indicated semi-quantitatively as absent (–), variable (±), positive (+) and positive with high expression level (++). BM HSCM also expressed CD45, MHCII and a co-stimulatory molecule CD86. BM HSCM were devoid of CD3, CD4, CD34, CD40, CD45R, Ly6G, CD117 and Sca-1.

HSCM differentiation was greatly dependent on MCSF. After HSC proliferation, the cells did not start to differentiate nor survived if MCSF was omitted. If MSCF was omitted after an initial trigger of monocytic differentiation with MCSF, overall cell survival was greatly reduced (Fig. 1D). Interestingly, if the HSCM were stimulated with LPS the cell survival increased back to the level with MCSF even though MCSF was not applied (Fig. 1D). This suggests HSCM growth was greatly dependent on MCSF as a growth factor, or on the inflammatory stimulus. The cells could thus adjust to their environment based on the conditions promoting or attenuating HSCM growth. BMM growth was slightly less dependent on MCSF, whereas microglia cell viability was independent of MCSF (Fig. 1E). This is reflected by the expression of MCSF receptor CD115 which was not detected in microglia and had lower expression in BMM than BM HSCM as described in Table 1.

BM HSCM respond to inflammatory stimulus by producing and secreting cytokines

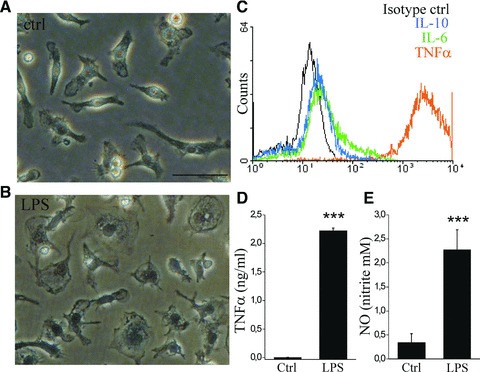

To study the physiology of BM HSCM as inflammatory cells, we stimulated the cells with LPS and determined the capability of cytokine production. LPS stimulation caused a classical change in monocytic cell morphology into an “ameboid” shape (Fig. 2A and B). LPS stimulation caused a high production of TNF-α particularly, whereas the production of other cytokines, IL-6 and IL-10 was low (Fig. 2C and D). LPS stimulation also induced a nitric oxide response (Fig. 2E). In more detail, when measured after 2 days of MCSF-differentiation, HSCM had a moderate TNF-α response to LPS (data not shown) and after 5 days of MCSF-differentiation, the TNF-α response to LPS was greatly increased. The TNF-α response to LPS was more pronounced in SSChi HSCM compared to SSClo, when measured as intracellular TNF-α production as well as when measured as secreted TNF-α assayed by flow cytometry and ELISA, respectively (data not shown). We also detected a similar discrepancy in BMM sub-populations, where monocytes with SSChi properties had high TNF-α production after stimulation with LPS. Furthermore, we detected a higher TNF-α response in type II than in type I microglia, when measured both as intracellular cytokine production and secreted cytokine (data not shown). Because BM HSCM, BMM and microglia had similar cytokine production profiles in respect of (i) very low spontaneous cytokine production without the inflammatory stimulus, (ii) high TNF-α production specifically and (iii) distinct cytokine production capacity in cell sub-populations we suggest BM HCSM to be functional inflammatory cells comparable to BMM and microglia.

Fig 2.

BM HSCM respond to inflammatory stimulus with producing cytokines and nitric oxide. The stimulation of BM HSCM with 10 ng/ml LPS induced a classical change in cell morphology (A,B). LPS-induced intracellular cytokine production was detected with flow cytometry (C), and was order of magnitude higher for TNF-α than other cytokines. TNF-α was also detected as high concentration of secreted cytokine analysed from the cell culture medium with ELISA (D, n = 6). LPS also induced a minor production of NO (E, n = 6). We did not detect a spontaneous cytokine production or a change into ameboid morphology in the absence of LPS. The data are shown after 5 days of MCSF differentiation. Scale bar = 50 μm.

BM HSCM are phagocytic cells and reduce Aβ burden in mouse model of AD

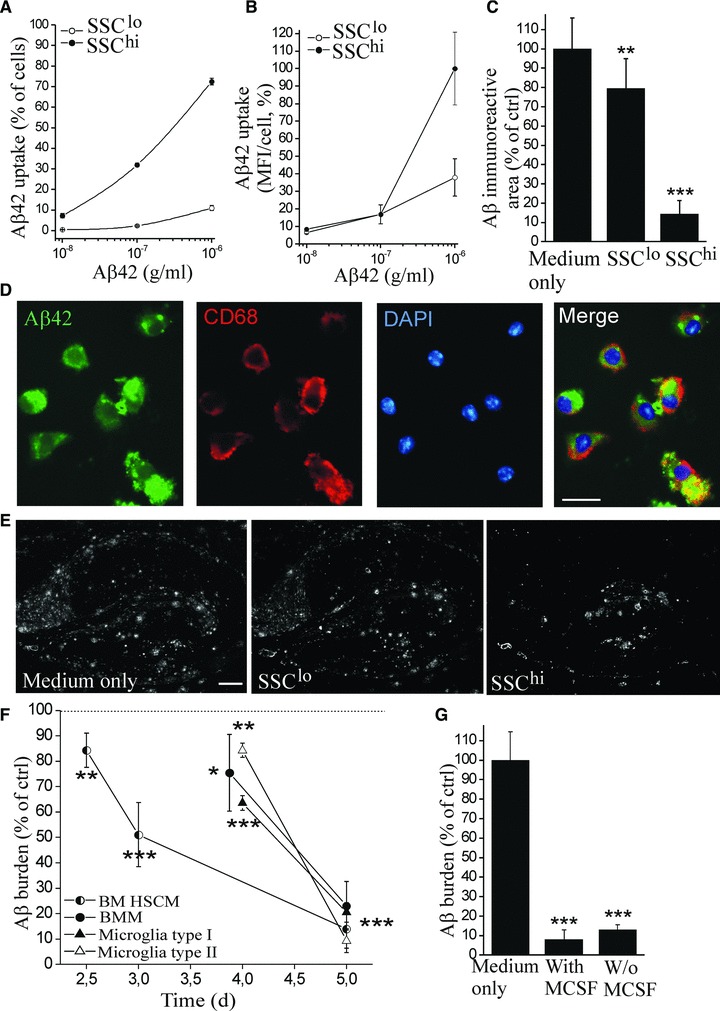

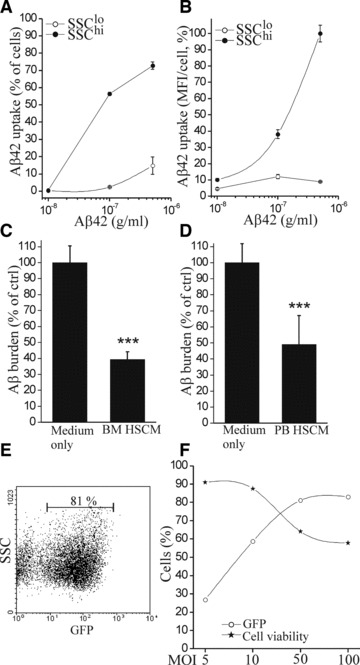

We next examined the potential of BM HSCM to reduce Aβ burden in AD. We have previously shown these cells to be capable of reducing Aβ burden ex vivo, and the reduction was not affected by an anti-inflammatory treatment with minocycline [27]. Here we studied the reduction of Aβ burden in more detail. When we incubated the BM HSCM with a fluorochrome-conjugated Aβ, we discovered that the cells were capable of taking up Aβ and that the uptake was much higher in SSChi HSCM compared to SSClo HSCM (Fig. 3A and B). The Aβ co-localized with CD68, a member of the lysosomal/endosomal-associated membrane glycoprotein family and a marker of lysosomes (Fig. 3D). When we applied BM HSCM on top of brain sections prepared from aged APdE9 mouse that have transgenes designed to accumulate Aβ in the brain, in the ex vivo model for Aβ phagocytosis described previously [8,27,37], we discovered that the clearance of Aβ from the hippocampus was indeed higher by SSChi HSCM compared to SSClo HSCM (Fig. 3C and E). We discovered BM HSCM, BMM and microglia to reduce the Aβ burden as quantified with ELISA (Fig. 3F). Interestingly, the time course of Aβ reduction was favourable to BM HSCM which reduced Aβ faster than BMM and microglia (Fig. 3F).

Fig 3.

BM HSCM reduce Aβ burden by phagocytosis. BM HSCM were incubated for 16 hrs with a fluorochrome-tagged Aβ42 and analysed with flow cytometry. The subpopulation of HSCM, SSChi, had high Aβ uptake as illustrated by percentage of cells with Aβ uptake and the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) in individual cells (A,B). The Aβ co-localized with CD68 in lysosomes (D). Also, SSChi HSCM cleared Aβ from the APdE9 mouse brain sections substantially (C,E, n = 8). To determine the reduction of total Aβ burden, the brain sections were analysed at different time points and quantified for the remaining Aβ42 with ELISA. BM HSCM, BMM and microglia reduced Aβ burden (F, n = 7–14/cell type). However, the BM HSCM reduced Aβ faster than the other cells (F). The phagocytosis of Aβ was not dependent on MCSF (G, n = 5–8). Scale bar = 25 μm (D) and 200 μm (E).

We studied the effect of certain co-stimulatory molecules and receptors or application of additional anti-inflammatory or inflammatory cytokines on Aβ reduction by BM HSCM. We did not detect any effect of blockade of CD36, CD40 or prostaglandin EP2 receptors or application of IL-4 or IL-1β cytokines on general cell viability or Aβ reduction capacity (data not shown). However, the cell survival was greatly dependent on function of vacuolar H+-ATPase (V-ATPase). When we blocked the V-ATPase with bafilomycin A1, the cells completely declined (data not shown). These data suggest that BM HSCM are highly phagocytic cells with pronounced lysosomal activity. The reduction of Aβ was not affected by MCSF. MCSF only affected HSCM survival, and when the cell amount was adjusted to obtain the same concentration of cells, the Aβ reduction capacity was identical in the presence and absence of MCSF (Fig. 3G). This suggests MCSF promotes cell growth but is not needed to boost their phagocytic capacity.

Intrahippocampally transplanted BM HSCM reduce Aβ burden in AD mouse model in vivo while retaining their phagocytic character

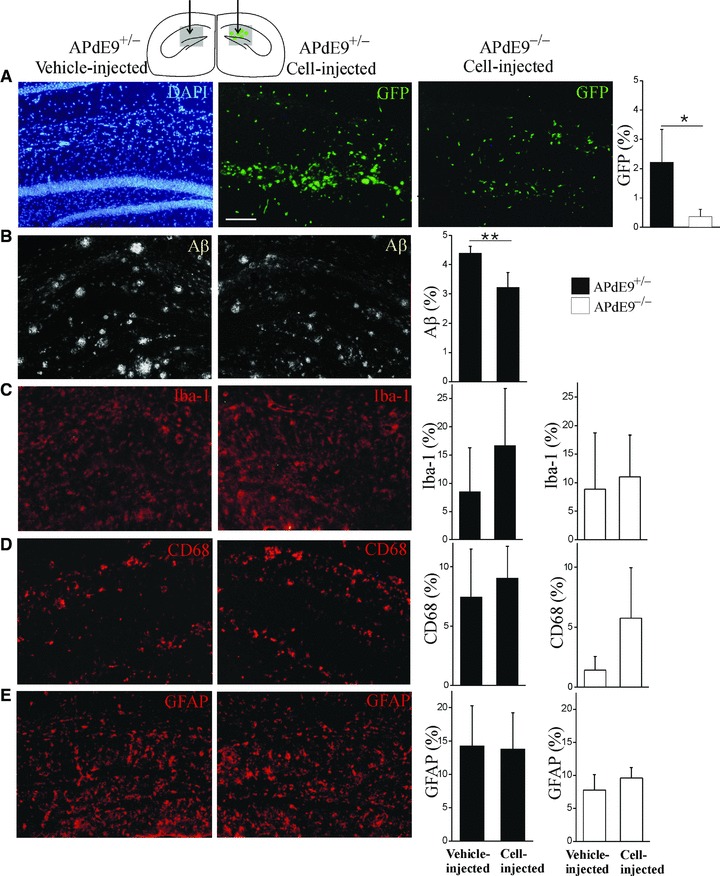

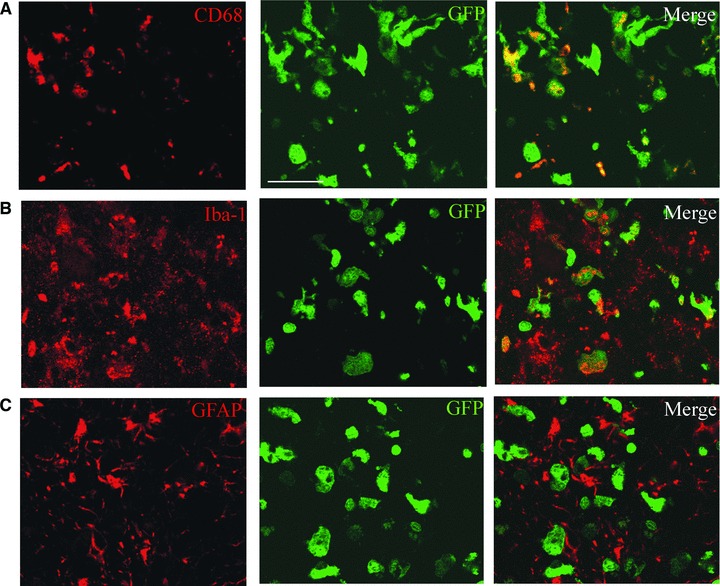

We next determined the therapeutic feasibility and function of BM HSCM in AD mouse model in vivo. We transplanted 300,000 BM HSCM obtained from eGFP-expressing mice unilaterally into the hippocampus, using contralateral vehicle transplantation as an injection control (Fig. 4A). The environment in the AD brain (APdE9+/−) enhanced the growth of HSCM when compared to the non-transgenic littermate (APdE9−/−) brain (Fig. 4A). HSCM reduced Aβ burden from the hippocampus (Fig. 4B) in the area occupied by transplanted cells. When Aβ burden was determined from the areas devoid of the transplanted HSCM, there was no reduction of Aβ (data not shown). HSCM transplantation did not increase the expression of Iba-1, CD68 and GFAP (Fig. 4C–E). Transplantation into non-transgenic littermates is shown as a comparison (Fig. 4A and C–E, open columns). When the brain sections were examined with confocal microscopy, we discovered that transplanted BM HSCM expressed mononuclear phagocyte markers Iba-1 and CD68 but not GFAP (Fig. 5A and C). The cells also expressed CD11b. The majority of HSCM expressed CD45 confirming their haematopoietic origin (data not shown).

Fig 4.

Transplanted BM HSCM integrate into AD model mouse brain and reduce Aβ burden in vivo. BM HSCM obtained from eGFP-mice were injected unilaterally into hippocampus, using contralateral vehicle-injection as a control (schematic figure). The area depicted in grey is enlarged below (A–E). Transplanted HSCM migrated along the granular layer of dentate gyrus and the molecular layer of lacunosum moleculare and invaded the parenchyma with variable extent. AD (APdE9+/−, black columns) brain conditions enhanced the survival of HSCM when compared to their wild-type (APdE9−/−, open columns) littermates (A, P < 0.05, n = 5 for AD and n = 4 for WT mice). BM HSCM reduced Aβ burden at the site of transplanted cells (B, P < 0.001, n = 5). Cell transplantation did not increase CD68, Iba-1 or GFAP immunoreactivity (C–E). Scale bar = 100 μm.

Fig 5.

BM HSCM retain their monocytic properties after transplantation in vivo. Intrahippocampally transplanted BM HSCM expressed CD68 and Iba-1 as detected with confocal microscopy. GFP co-localizes with CD68 and Iba-1 immunoreactivity in majority of the cells (A, B) but not with GFAP in any cells (C). Scale bar = 50 μm.

Lentivirally transduced BM HSC retain their haematopoietic reconstitution capacity and differentiate into functional monocytic cells

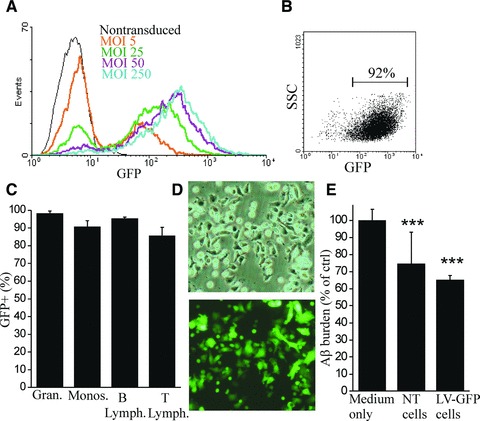

Transduction of BM HSC with a lentivirus construct expressing eGFP as a reporter gene (LV-GFP) was achieved using a low virus concentration. Transduction efficiency was high, reaching the maximum at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 50 (Fig. 6A and B). LV-GFP did not affect cell viability. When lethally irradiated mice were transplanted with LV-GFP transduced BM HSC, the cells engrafted and fully reconstituted the haematopoietic system, showing long-term gene expression (Fig. 6C). This suggests that long-term HSC can be genetically modified, retain their differentiation ability and result in long-lasting gene expression in haematopoietic cells in vivo. We next examined the effect of lentiviral transduction on BM HSC differentiation in vitro. After LV-GFP transduction, BM HSC proliferated and differentiated normally in the presence of MCSF and GFP expression was retained in all cells (Fig. 6D). When we applied the cells into Aβ phagocytosis assay ex vivo, we discovered that LV-GFP transduced BM HSCM reduced Aβ burden similarly to non-transduced cells (Fig. 6E). This suggests that lentivirally transduced cells also retain their functional activity.

Fig 6.

Lentivirally transduced BM HSC differentiate into functional monocytic cells. BM HSC were transduced with LV-GFP. BM HSC were transduced with high efficiency with low MOI (A, B). The blot is gated according to non-transduced (NT) cells, which had ≤1% of the events on gated area (B, indicated with a bar). LV-GFP did not decrease cell viability (data not shown). When LV-GFP transduced BM HSC were transplanted into lethally irradiated mice, the cells engrafted and fully reconstituted the haematopoietic system, showing long-term gene expression 7–9 months after the transplantation (C, n = 4). The expression of GFP was determined with flow cytometry from peripheral blood granulocytes, monocytes, B and T lymphocytes with Gr-1, CD11b, CD45R and CD3 antibodies, respectively. After lentiviral transduction, BM HSC differentiated normally into monocytic cells in the presence of MCSF in vitro and GFP expression was retained in all cells (D). When LV-GFP transduced cells were applied into Aβ phagocytosis assay ex vivo, BM HSCM reduced Aβ burden from APdE9 mouse hippocampus similar to non-transduced cells (E, n = 4–7), showing normal functional activity.

Human HSCM capable of Aβ phagocytosis can be obtained from BM as well as GCSF-mobilized PB HSC

When we applied the protocol described earlier to human PB or BM HSC, they behaved in a similar manner to mouse HSC. The cells differentiated in a similar time course as mouse HSC and they also formed dual subpopulations of cells with different adherence and SSC properties. The cells were morphologically identical to corresponding HSCM of mouse origin. Because of discrepancies in the expression profile between human and mouse monocytes [33], we stained human HSCM with a slightly different set of markers. We determined human HSCM to express CD14, CD11b, CD11c, CD68 and CCR2. Differentiated cells did not express CD34 or CD16.

Similarly to mouse cells, we discovered that the Aβ uptake of human BM HSCM was much higher in SSChi HSCM compared to SSClo HSCM (Fig. 7A and B). Intracellular Aβ co-localized with CD68 in lysosomes (data not shown). When we applied BM HSCM on top of brain sections prepared from aged APdE9 mouse, we found that human BM HSCM indeed reduce Aβ burden (Fig. 7C). The insufficient number of transplantable cells is considered as one of the major limiting factors in cell therapy. In addition to cell proliferation in vitro, we tested whether the mobilization of HSC can be utilized for increasing the yield of stem cells. After administration of GCSF to mice, the number of CD117+ HSC in BM rose over three-fold. When GCSF-mobilized mouse BM HSC were transplanted into irradiated mouse, they fully reconstituted the haematopoietic system and was sustained for at least 6 months (data not shown). This suggests that GCSF-mobilized HSC are long-term stem cells and capable of multi-lineage differentiation in vivo. Furthermore, the GCSF-mobilized HSC proliferated and differentiated normally into monocytic cells displaying similar characteristics to naive BM HSCM in vitro (data not shown). Finally, we differentiated human HSC originated from GCSF-mobilized PB into monocytic cells and examined their ability to phagocytose Aβ with the ex vivo assay. Human PB HSCM were fully functional in reduction of Aβ burden (Fig. 7D).

Fig 7.

Human BM and PB HSC differentiate into monocytic cells and reduce Aβ burden by phagocytosis. Human BM HSCM SSChi cells had high uptake of Aβ (A, B). When BM HSCM were applied on top of brain sections prepared from aged APdE9 mouse, they reduced Aβ burden (C, P < 0.001, n = 6). Similarly, human HSC originated from GCSF-mobilized PB differentiated into monocytic cells and reduced Aβ burden when assayed ex vivo (D, P < 0.001, n = 8). Human HSC were transduced with LV-GFP with high efficiency (E). The excess concentration of virus decreased the cell viability. For optimal cell integrity, the transduction efficiency is ought to be compromised with lowering the virus concentration to <50 MOI.

To investigate the feasibility of using human HSCM in potential cell therapy, we also studied whether they can be lentivirally modified similar to mouse HSC. Human HSC could be lentivirally transduced with high efficiency (Fig. 7E and F) and reached the maximum with low virus concentration of 50 MOI. When we assessed cell survival, we noticed that the virus transduction started to lower cell viability at 10 MOI. Therefore, a balance needs to be met in order to use the lowest—but sufficient—virus concentration to have minimum impact on HSC viability.

Discussion

BM-derived cells have been shown to potentially alleviate Aβ burden in AD [25-28]. Currently, the particular BM cells that can migrate to the brain parenchyma have not been definitively identified, although the involvement of Ly6C, CD11b and CCR2 has been suggested [29-31]. In this study we demonstrate a method to obtain monocytic cells from BM HSC and characterize them in vitro. These cells express the factors suggested to be necessary for cell migration and they are functional monocytic cells with response to inflammation and capacity for Aβ reduction as we demonstrated in vitro and in vivo. HSC could be lentivirally modified with high efficiency and without compromising monocytic differentiation and function. Finally, we show that monocytic cells can be obtained from human BM and also GCSF-mobilized PB HSC, which suggests a potential cellular therapy for AD.

It has been recently demonstrated that BM progenitors obtained by lineage depletion differentiate into small round microglia-type cells with high proliferative capacity in a primary mixed glia co-culture and can also transform into large flat microglia-type cells in the presence of MCSF without glia co-culture [48]. Thus, co-culturing with glial cells enhanced the round cell versus flat cell phenotype. In this study, we demonstrate that BM HSC obtained by positive selection differentiate into both round and flat phenotypes, in the presence of MCSF without the additional support from glial cells. We therefore suggest that differentiation into subtypes is an intrinsic property of monocytic differentiation and does not require additional factors provided by glia. Early differentiating BM HSC displayed subpopulations of non-attached round cells and attached flat cells, but favoured the attached phenotype after a longer differentiation period. Because non-attached and attached HSCM had differing Ly6C expression, this factor potentially plays a role in cell motility and differentiation processes but is not directly needed for cell activation and function: attached HSCM with low Ly6C expression exhibited higher phagocytic capacity than non-attached HSCM with high Ly6C expression.

BM HSC differentiation into monocytic cells and the monocytic cell survival was highly dependent on MCSF. It has been shown previously that long-term MCSF treatment in early AD increases the number of microglia in the brain, enhances Aβ phagocytosis and improves cognitive impairment [49] suggesting a promoting effect of MCSF on microglia or monocytic cell growth in vivo. Also, lower plasma levels of MCSF were found in AD patients and in people with mild cognitive impairment who developed AD within few years [50]. The effect of MCSF on monocyte and macrophage differentiation is well acknowledged [51, 52] when obtained from HSC or induced pluripotent stem cells [53, 54]. HSC as a monocytic cell origin is currently a more accessible approach for potential stem cell therapy: HSC mobilization and collection is a current clinical procedure approved and applied in haematological malignancies.

BM HSCM reduced Aβ burden by phagocytosis because the internalized Aβ peptide was found in co-localization with the lysosomal protein CD68. Lysosomal activity was crucial for HSCM cell viability: the blockade of the membrane pump maintaining low lysosomal pH and proper lysosomal function eventually lead to cell degeneration. On the other hand, HSCM’s resistance to unfavourable conditions such as Aβ-laden brain parenchyma or inflammatory stimulus was remarkably good. The HSCM cell viability was actually enhanced under inflammatory stimulus in vitro as well as in the AD brain environment in vivo. Furthermore, BM HSCM phagocytosed natively formed brain Aβ deposits and indeed, degraded internalized Aβ. They did not, however, contribute to formation of Aβ plaques preceded by Aβ internalization and accumulation into intracellular vesicles [55], as suggested for some phagocytosis-competent monocytes.

There are two main subsets of monocytes in the blood; inflammatory CCR2+Ly6C+/highCD115+ and resident CCR2−Ly6C−/lowCD115+, which display different migration properties and function in inflamed and non-inflamed tissues [56]. Ly6C+ monocytes may be recruited to the injured area with phagocytic and inflammatory cytokine activity, whereas Ly6C− may participate in patrolling the blood vessels in steady-state conditions and be recruited to injured area later than Ly6C+ monocytes and contribute to wound repair, tissue remodelling and immunomodulation [33]. Because Ly6C+ monocytes can lose their expression of Ly6C [57-60], it is not easy to categorize BM HSCM into these two classes. HSCM had higher Ly6C expression in early differentiation which nearly ceased during differentiation and the phenotype changed into macrophage-like cells. However, our Ly6C− HSCM appeared to have higher phagocytic capacity indicating that Ly6C expression was not associated with the observed classical pro-inflammatory phenotype. Infiltrating anti-inflammatory monocytes have been shown to facilitate Aβ clearance [61]. It remains to be shown how the BM HSCM sub-populations based on SSC or Ly6C properties, migrate into the brain and whether these cells represent the parenchymal and perivascular [62] cell populations involved in AD [25-28].

BM HSC could be lentivirally modified with long-term transgene expression without compromising cell differentiation or function as also shown in PB HSC [63]. Recently, lentivirally mediated gene therapy was shown to provide clinical benefits in an inheritable fatal demyelinating disease X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy [64]. HSC were transduced ex vivo to restore dysfunctional protein function and proper myelin maintenance and transplanted after myeloablative treatment. Even though less than 15% of leucocytes expressed the transgene, the progressive cerebral demyelination ceased. This suggests that introducing genetically modified leucocytes may work as a therapeutic approach, potentially also for other diseases. Microglia [14] and monocyte function [40,65] may be defective in AD. Introducing fresh monocytic cells into the circulation, whether migrating into the brain and acting as BM-derived microglia in the CNS or circulating in the periphery, may contribute to inflammatory activities in AD, reduction of Aβ and ameliorating AD pathology. It is still under debate which conditions are needed for cell migration: compromised BBB integrity or disease-induced conditions in the brain parenchyma [30,66] and to which extent the migration may occur [67, 68]. Gene modification may be utilized not only to enhance the migration of HSCM into the target area and promote their survival and function as cell-based therapy, but HSCM could also work as carriers for the therapeutic gene. We suggest HSCM to be utilized in future studies and novel therapeutics for AD.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Academy of Finland and the Finnish Funding Agency for Technology and Innovation. We thank Ms. Mirka Tikkanen for technical assistance with immunohistochemistry, Ms. Laila Kaskela for technical assistance with cell cultures and Ms. Sara Wojciechowski for assistance with flow cytometry. J.M. performed in vitro experiments and wrote the paper. E.S., T.M., T.R., E.P. and J.A. performed in vivo studies. E.S., P.V. and S.L. participated in in vitro studies. E.J. and P.L. provided essential tools and expertise on human cells. A.M., M.K. and J.K. designed the study and contributed to the writing.

Conflicts of interest

The authors confirm that there are no conflicts of interest.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

List of primary antibodies used in flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell is not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

References

- 1.Querfurth HW, LaFerla FM. Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:329–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0909142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Strooper B. Proteases and proteolysis in Alzheimer disease: a multifactorial view on the disease process. Physiol Rev. 2010;90:465–94. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00023.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aguzzi A, O’Connor T. Protein aggregation diseases: pathogenicity and therapeutic perspectives. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:237–48. doi: 10.1038/nrd3050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nielsen HM, Mulder SD, Belien JA, et al. Astrocytic A beta 1–42 uptake is determined by A beta-aggregation state and the presence of amyloid-associated proteins. Glia. 2010;58:1235–46. doi: 10.1002/glia.21004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D’Andrea MR, Cole GM, Ard MD. The microglial phagocytic role with specific plaque types in the Alzheimer disease brain. Neurobiol Aging. 2004;25:675–83. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2003.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mandrekar S, Jiang Q, Lee CY, et al. Microglia mediate the clearance of soluble Abeta through fluid phase macropinocytosis. J Neurosci. 2009;29:4252–62. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5572-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Michelucci A, Heurtaux T, Grandbarbe L, et al. Characterization of the microglial phenotype under specific pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory conditions: effects of oligomeric and fibrillar amyloid-beta. J Neuroimmunol. 2009;210:3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koistinaho M, Lin S, Wu X, et al. Apolipoprotein E promotes astrocyte colocalization and degradation of deposited amyloid-beta peptides. Nat Med. 2004;10:719–26. doi: 10.1038/nm1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wyss-Coray T, Loike JD, Brionne TC, et al. Adult mouse astrocytes degrade amyloid-beta in vitro and in situ. Nat Med. 2003;9:453–7. doi: 10.1038/nm838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pihlaja R, Koistinaho J, Malm T, et al. Transplanted astrocytes internalize deposited beta-amyloid peptides in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Glia. 2008;56:154–63. doi: 10.1002/glia.20599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rogers J, Strohmeyer R, Kovelowski CJ, Li R. Microglia and inflammatory mechanisms in the clearance of amyloid beta peptide. Glia. 2002;40:260–9. doi: 10.1002/glia.10153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Floden AM, Combs CK. Beta-amyloid stimulates murine postnatal and adult microglia cultures in a unique manner. J Neurosci. 2006;26:4644–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4822-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilcock DM, Munireddy SK, Rosenthal A, et al. Microglial activation facilitates Abeta plaque removal following intracranial anti-Abeta antibody administration. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;15:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2003.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hickman SE, Allison EK, El KhouryJ. Microglial dysfunction and defective beta-amyloid clearance pathways in aging Alzheimer’s disease mice. J Neurosci. 2008;28:8354–60. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0616-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ransohoff RM, Perry VH. Microglial physiology: unique stimuli, specialized responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:119–45. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Polazzi E, Monti B. Microglia and neuroprotection: from in vitro studies to therapeutic applications. Prog Neurobiol. 2010;92:293–315. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2010.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eglitis MA, Mezey E. Hematopoietic cells differentiate into both microglia and macroglia in the brains of adult mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:4080–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.4080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kennedy DW, Abkowitz JL. Mature monocytic cells enter tissues and engraft. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:14944–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Priller J, Flugel A, Wehner T, et al. Targeting gene-modified hematopoietic cells to the central nervous system: use of green fluorescent protein uncovers microglial engraftment. Nat Med. 2001;7:1356–61. doi: 10.1038/nm1201-1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Asheuer M, Pflumio F, Benhamida S, et al. Human CD34+ cells differentiate into microglia and express recombinant therapeutic protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:3557–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306431101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simard AR, Rivest S. Bone marrow stem cells have the ability to populate the entire central nervous system into fully differentiated parenchymal microglia. FASEB J. 2004;18:998–1000. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1517fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davoust N, Vuaillat C, Cavillon G, et al. Bone marrow CD34+/B220+ progenitors target the inflamed brain and display in vitro differentiation potential toward microglia. FASEB J. 2006;20:2081–92. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5593com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ladeby R, Wirenfeldt M, Dalmau I, et al. Proliferating resident microglia express the stem cell antigen CD34 in response to acute neural injury. Glia. 2005;50:121–31. doi: 10.1002/glia.20159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stalder AK, Ermini F, Bondolfi L, et al. Invasion of hematopoietic cells into the brain of amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2005;25:11125–32. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2545-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simard AR, Soulet D, Gowing G, et al. Bone marrow-derived microglia play a critical role in restricting senile plaque formation in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron. 2006;49:489–502. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malm TM, Koistinaho M, Parepalo M, et al. Bone-marrow-derived cells contribute to the recruitment of microglial cells in response to beta-amyloid deposition in APP/PS1 double transgenic Alzheimer mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2005;18:134–42. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malm TM, Magga J, Kuh GF, et al. Minocycline reduces engraftment and activation of bone marrow-derived cells but sustains their phagocytic activity in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Glia. 2008;56:1767–79. doi: 10.1002/glia.20726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hawkes CA, McLaurin J. Selective targeting of perivascular macrophages for clearance of beta-amyloid in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:1261–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805453106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.El KhouryJ, Toft M, Hickman SE, et al. Ccr2 deficiency impairs microglial accumulation and accelerates progression of Alzheimer-like disease. Nat Med. 2007;13:432–8. doi: 10.1038/nm1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mildner A, Schmidt H, Nitsche M, et al. Microglia in the adult brain arise from Ly-6ChiCCR2+ monocytes only under defined host conditions. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1544–53. doi: 10.1038/nn2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lebson L, Nash K, Kamath S, et al. Trafficking CD11b-positive blood cells deliver therapeutic genes to the brain of amyloid-depositing transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2010;30:9651–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0329-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gordon S, Taylor PR. Monocyte and macrophage heterogeneity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:953–64. doi: 10.1038/nri1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Auffray C, Sieweke MH, Geissmann F. Blood monocytes: development, heterogeneity, and relationship with dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:669–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Swirski FK, Nahrendorf M, Etzrodt M, et al. Identification of splenic reservoir monocytes and their deployment to inflammatory sites. Science. 2009;325:612–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1175202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burke B, Sumner S, Maitland N, et al. Macrophages in gene therapy: cellular delivery vehicles and in vivo targets. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;72:417–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hanisch UK, van Rossum D, Xie Y, et al. The microglia-activating potential of thrombin: the protease is not involved in the induction of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:51880–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408318200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Magga J, Puli L, Pihlaja R, et al. Human intravenous immunoglobulin provides protection against Abeta toxicity by multiple mechanisms in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuroinflammation. 2010;7:1–15. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-7-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saura J, Tusell JM, Serratosa J. High-yield isolation of murine microglia by mild trypsinization. Glia. 2003;44:183–9. doi: 10.1002/glia.10274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wojciechowski S, Tripathi P, Bourdeau T, et al. Bim/Bcl-2 balance is critical for maintaining naive and memory T cell homeostasis. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1665–75. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fiala M, Liu PT, Espinosa-Jeffrey A, et al. Innate immunity and transcription of MGAT-III and Toll-like receptors in Alzheimer’s disease patients are improved by bisdemethoxycurcumin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:12849–54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701267104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jankowsky JL, Fadale DJ, Anderson J, et al. Mutant presenilins specifically elevate the levels of the 42 residue beta-amyloid peptide in vivo: evidence for augmentation of a 42-specific gamma secretase. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:159–70. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kanninen K, Heikkinen R, Malm T, et al. Intrahippocampal injection of a lentiviral vector expressing Nrf2 improves spatial learning in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:16505–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908397106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Okabe M, Ikawa M, Kominami K, et al. ‘Green mice’ as a source of ubiquitous green cells. FEBS Lett. 1997;407:313–9. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00313-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dobrenis K. Microglia in cell culture and in transplantation therapy for central nervous system disease. Methods. 1998;16:320–44. doi: 10.1006/meth.1998.0688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Imhof BA, Aurrand-Lions M. Adhesion mechanisms regulating the migration of monocytes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:432–44. doi: 10.1038/nri1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shechter R, London A, Varol C, et al. Infiltrating blood-derived macrophages are vital cells playing an anti-inflammatory role in recovery from spinal cord injury in mice. PLoS Med. 2009;6:1–17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shimizu E, Kawahara K, Kajizono M, et al. IL-4-induced selective clearance of oligomeric beta-amyloid peptide(1–42) by rat primary type 2 microglia. J Immunol. 2008;181:6503–13. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.6503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Noto D, Takahashi K, Miyake S, Yamada Y. In vitro differentiation of lineage-negative bone marrow cells into microglia-like cells. Eur J Neurosci. 2010;31:1155–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boissonneault V, Filali M, Lessard M, et al. Powerful beneficial effects of macrophage colony-stimulating factor on beta-amyloid deposition and cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2009;132:1078–92. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ray S, Britschgi M, Herbert C, et al. Classification and prediction of clinical Alzheimer’s diagnosis based on plasma signaling proteins. Nat Med. 2007;13:1359–62. doi: 10.1038/nm1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stec M, Weglarczyk K, Baran J, et al. Expansion and differentiation of CD14+CD16(−) and CD14++CD16+ human monocyte subsets from cord blood CD34+ hematopoietic progenitors. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;82:594–602. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0207117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Way KJ, Dinh H, Keene MR, et al. The generation and properties of human macrophage populations from hemopoietic stem cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;85:766–78. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1108689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Senju S, Haruta M, Matsunaga Y, et al. Characterization of dendritic cells and macrophages generated by directed differentiation from mouse induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells. 2009;27:1021–31. doi: 10.1002/stem.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Choi KD, Yu J, Smuga-Otto K, et al. Hematopoietic and endothelial differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells. 2009;27:559–67. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Friedrich RP, Tepper K, Ronicke R, et al. Mechanism of amyloid plaque formation suggests an intracellular basis of Abeta pathogenicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:1942–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904532106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Geissmann F, Jung S, Littman DR. Blood monocytes consist of two principal subsets with distinct migratory properties. Immunity. 2003;19:71–82. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00174-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sunderkotter C, Nikolic T, Dillon MJ, et al. Subpopulations of mouse blood monocytes differ in maturation stage and inflammatory response. J Immunol. 2004;172:4410–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.7.4410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Arnold L, Henry A, Poron F, et al. Inflammatory monocytes recruited after skeletal muscle injury switch into antiinflammatory macrophages to support myogenesis. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1057–69. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Varol C, Landsman L, Fogg DK, et al. Monocytes give rise to mucosal, but not splenic, conventional dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:171–80. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Landsman L, Varol C, Jung S. Distinct differentiation potential of blood monocyte subsets in the lung. J Immunol. 2007;178:2000–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.4.2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Town T, Laouar Y, Pittenger C, et al. Blocking TGF-beta-Smad2/3 innate immune signaling mitigates Alzheimer-like pathology. Nat Med. 2008;14:681–7. doi: 10.1038/nm1781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hess DC, Abe T, Hill WD, et al. Hematopoietic origin of microglial and perivascular cells in brain. Exp Neurol. 2004;186:134–44. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tesio M, Gammaitoni L, Gunetti M, et al. Sustained long-term engraftment and transgene expression of peripheral blood CD34+ cells transduced with third-generation lentiviral vectors. Stem Cells. 2008;26:1620–7. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cartier N, Hacein-Bey-Abina S, Bartholomae CC, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy with a lentiviral vector in X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy. Science. 2009;326:818–23. doi: 10.1126/science.1171242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zaghi J, Goldenson B, Inayathullah M, et al. Alzheimer disease macrophages shuttle amyloid-beta from neurons to vessels, contributing to amyloid angiopathy. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;117:111–24. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0481-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ajami B, Bennett JL, Krieger C, et al. Local self-renewal can sustain CNS microglia maintenance and function throughout adult life. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1538–43. doi: 10.1038/nn2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Soulet D, Rivest S. Bone-marrow-derived microglia: myth or reality? Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2008;8:508–18. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Prinz M, Mildner A. Microglia in the CNS: immigrants from another world. Glia. 2011;59:177–87. doi: 10.1002/glia.21104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

List of primary antibodies used in flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry