Abstract

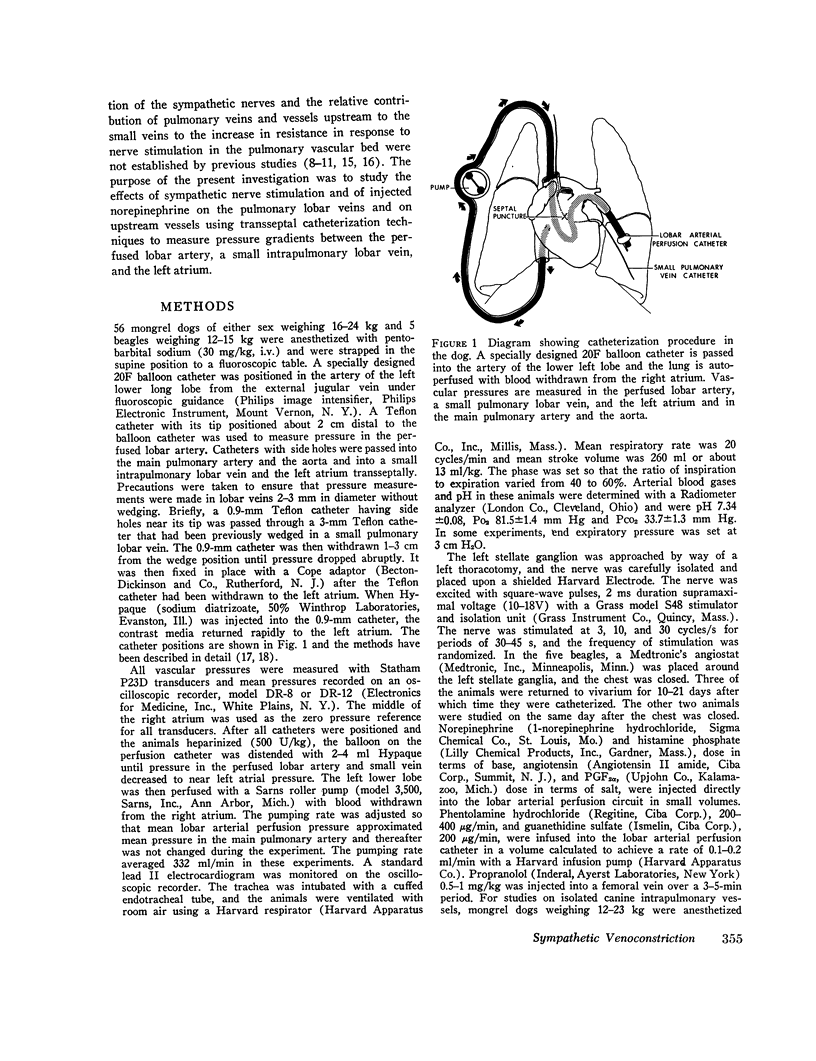

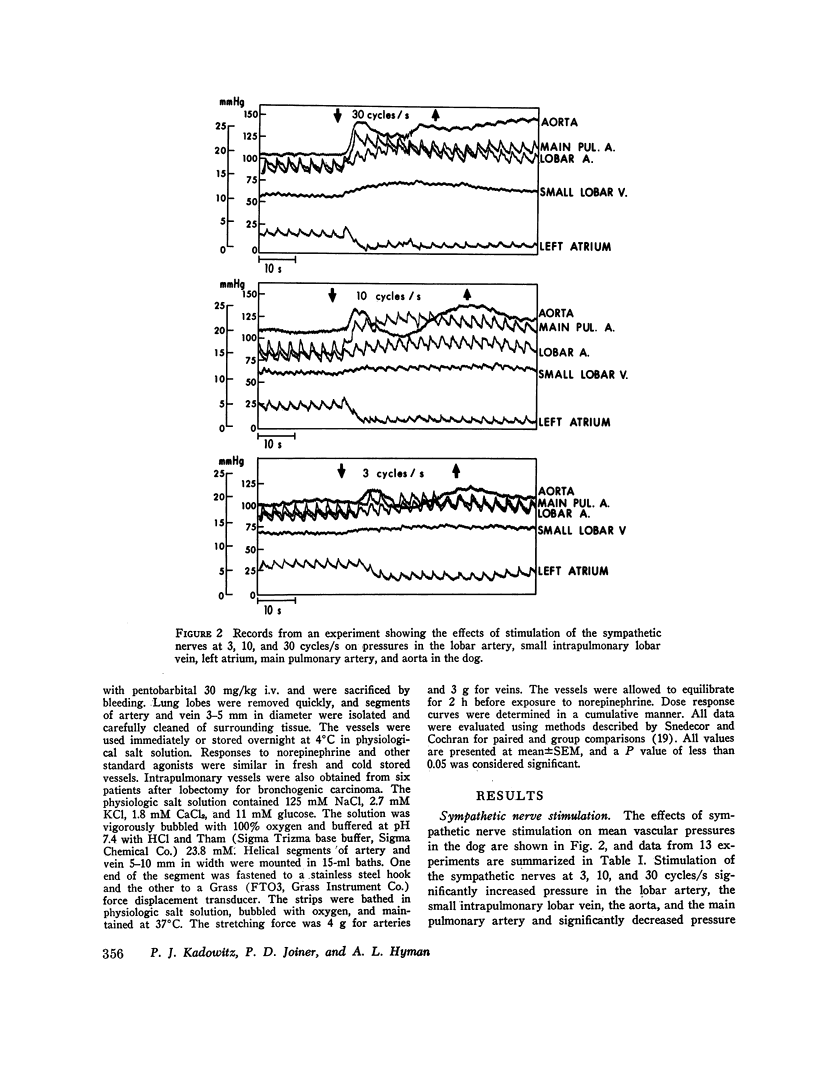

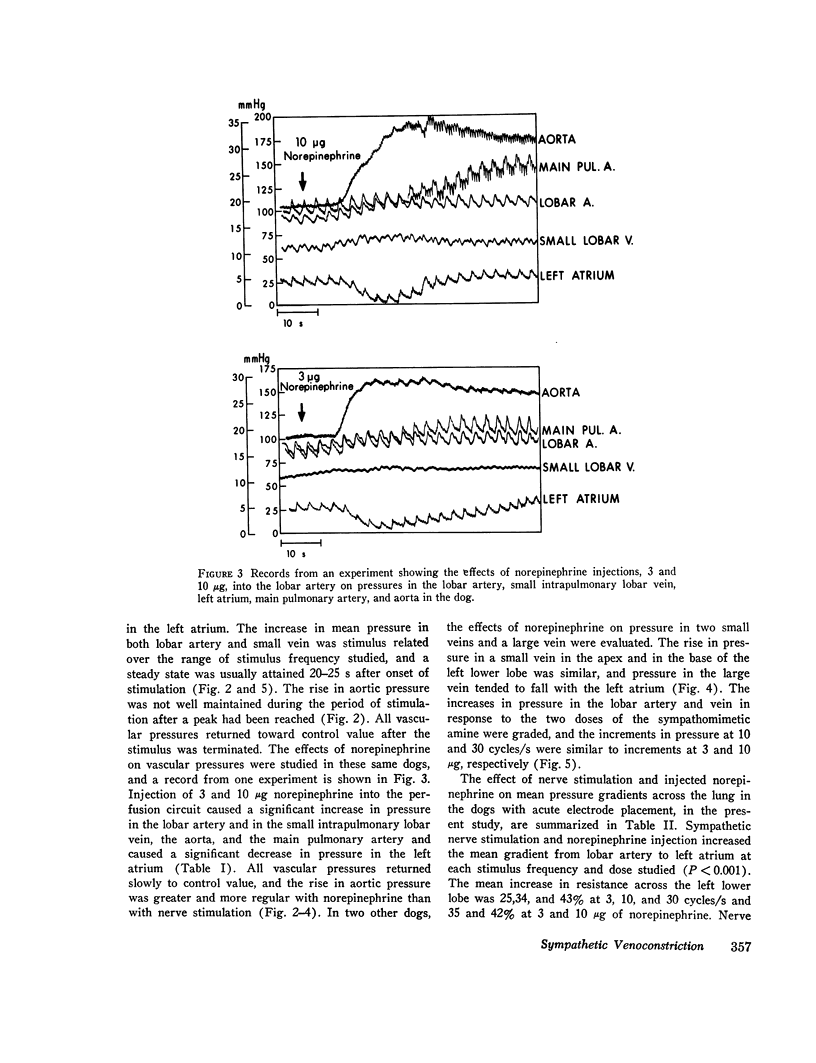

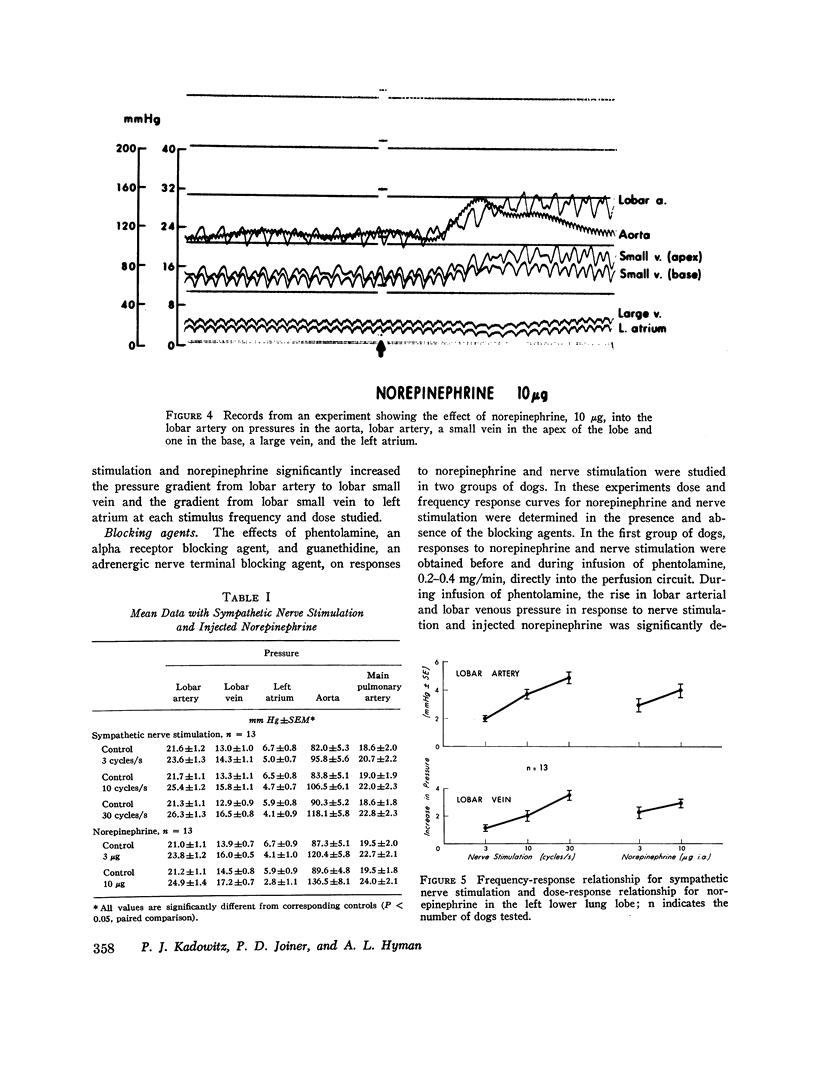

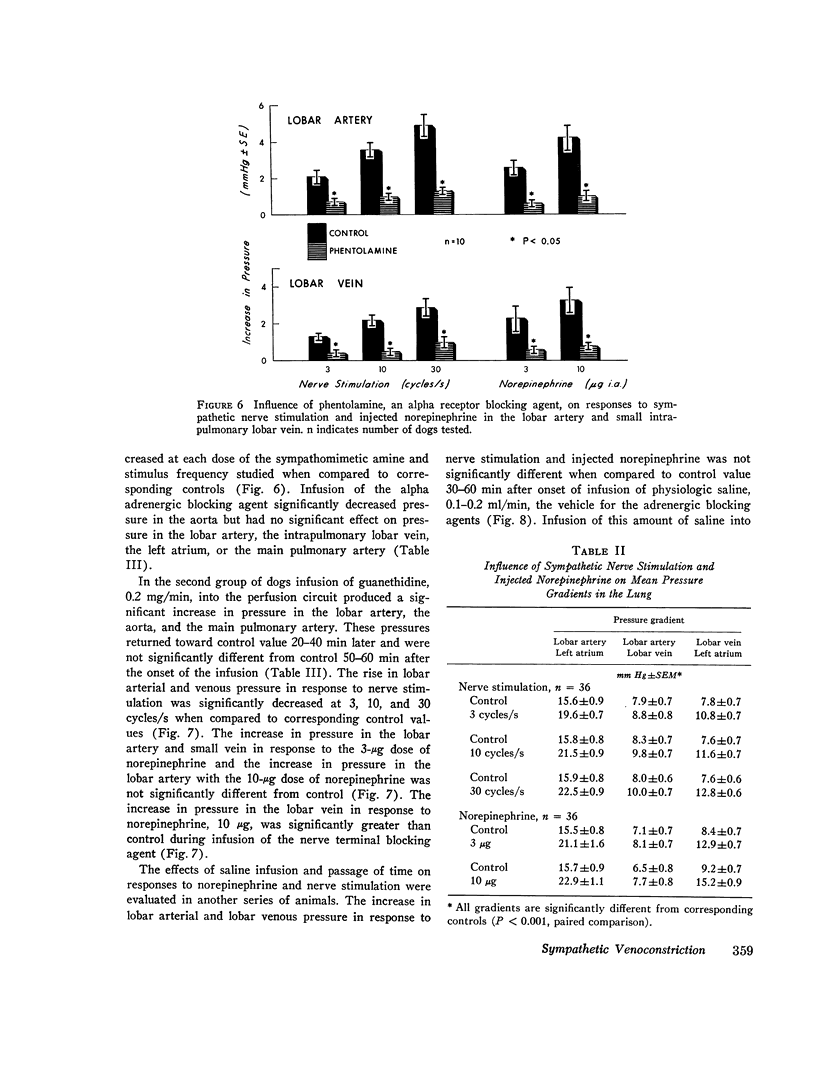

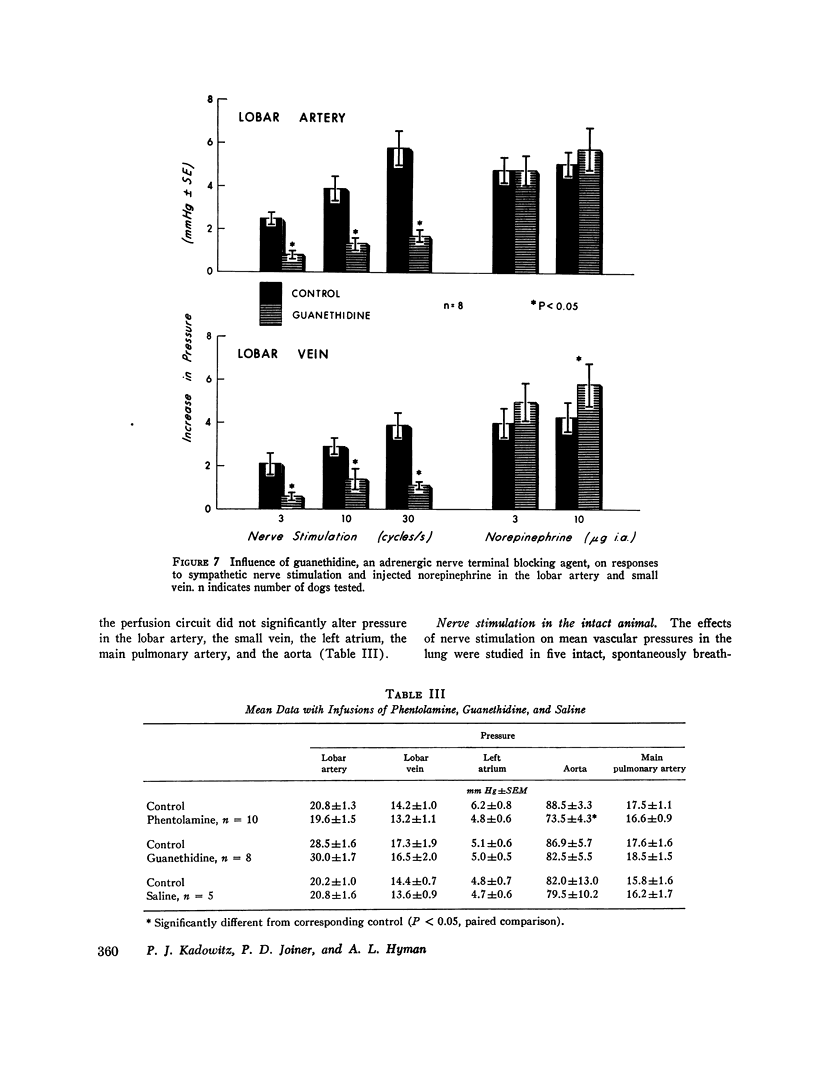

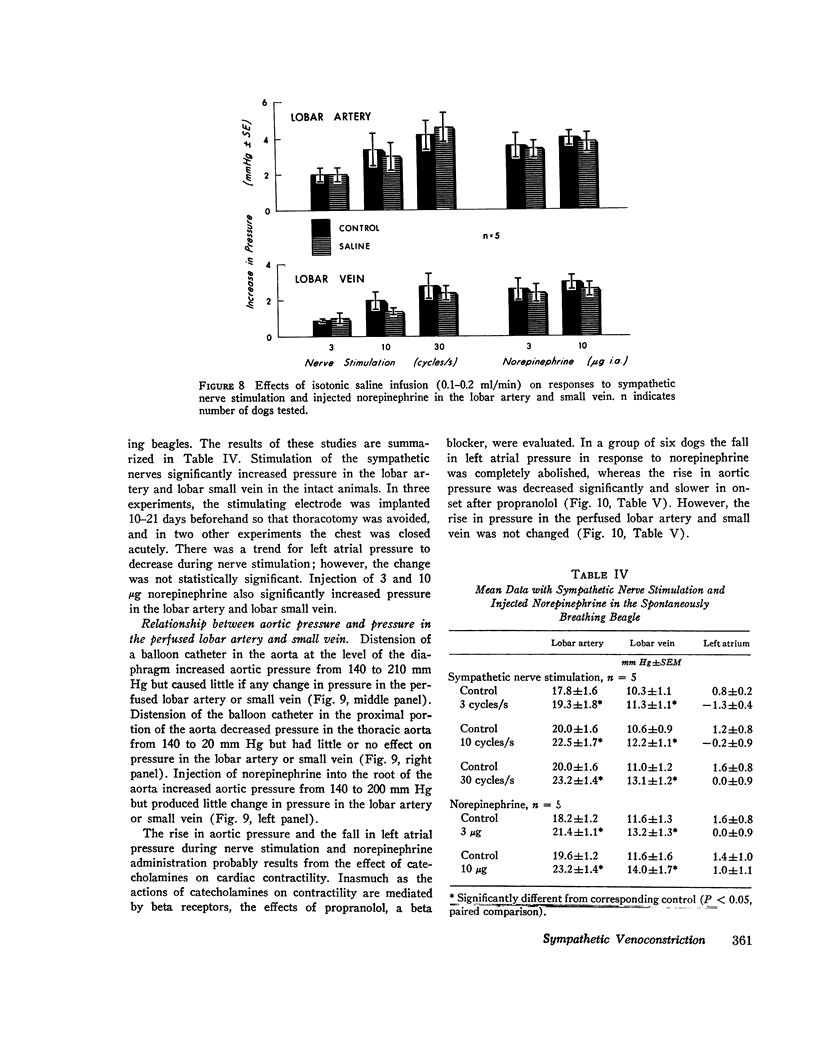

The contribution of the intrapulmonary lobar veins to the increase in pulmonary vascular resistance in response to sympathetic stimulation was studied under conditions of controlled blood flow in the anesthetized dog in which vascular pressures were measured simultaneously in the perfused lobar artery, an intrapulmonary lobar vein 2-3 mm in diameter and in the left atrium. Stimulation of the stellate ganglia at 3, 10, and 30 cycles/s increased pressure in the lobar artery and small vein in a stimulus-related manner but decreased pressure in the left atrium. Injection of norepinephrine into the perfused lobar artery also increased pressure in the lobar artery and small vein but decreased pressure in the left atrium. The increase in lobar arterial and venous pressure in response to either injected norepinephrine or to nerve stimulation was antagonized by an alpha receptor blocking agent. The rise in pressure in both labor artery and small vein with nerve stimulation but not administered norepinephrine was inhibited by an adrenergic nerve terminal blocking agent. The results suggest that under conditions of steady flow, sympathetic nerve stimulation increases the resistance to flow in the lung by constricting pulmonary veins and vessels upstream to the small veins, and that at each stimulus-frequency studied approximately 50% of the total increase in resistance may be due to venoconstriction. It is concluded that the increase in resistance to flow in the lung in response to nerve stimulation is thre result of activation of alpha adrenergic receptors by norephinephrine liberated from adrenergic nerve terminals in venous segments and in vessels upstream to samll veins, presumed to be small arteries.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- DALY I. D. An analysis of active and passive effects on the pulmonary vascular bed in response to pulmonary nerve stimulation. Q J Exp Physiol Cogn Med Sci. 1961 Jul;46:257–271. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1961.sp001542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DE DALY I B. Intrinsic mechanisms of the lung. Q J Exp Physiol Cogn Med Sci. 1958 Jan;43(1):2–26. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1958.sp001304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly I. de B., Ramsay D. J., Waaler B. A. The cite of action of nerves in the pulmonary vascular bed in the dog. J Physiol. 1970 Aug;209(2):317–339. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1970.sp009167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ELIAKIM M., AVIADO D. M. Effects of nerve stimulation and drugs on the extrapulmonary portion of the pulmonary vein. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1961 Sep;133:304–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillenz M. Innervation of pulmonary and bronchial blood vessels of the dog. J Anat. 1970 May;106(Pt 3):449–461. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman A. L. Effects of large increases in pulmonary blood flow on pulmonary venous pressure. J Appl Physiol. 1969 Aug;27(2):179–185. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1969.27.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman A. L., Woolverton W. C., Guth P. S., Ichinose H. The pulmonary vasopressor response to decreases in blood pH in intact dogs. J Clin Invest. 1971 May;50(5):1028–1043. doi: 10.1172/JCI106574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram R. H., Jr, Szidon J. P., Fishman A. P. Response of the main pulmonary artery of dogs to neuronally released versus blood-borne norepinephrine. Circ Res. 1970 Feb;26(2):249–262. doi: 10.1161/01.res.26.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram R. H., Szidon J. P., Skalak R., Fishman A. P. Effects of sympathetic nerve stimulation on the pulmonary arterial tree of the isolated lobe perfused in situ. Circ Res. 1968 Jun;22(6):801–815. doi: 10.1161/01.res.22.6.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadowitz P. J., Hyman A. L. Effect of sympathetic nerve stimulation on pulmonary vascular resistance in the dog. Circ Res. 1973 Feb;32(2):221–227. doi: 10.1161/01.res.32.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadowitz P. J., Joiner P. D., Hyman A. L. Differential effects of phentolamine and bretylium on pulmonary vascular responses to norepinephrine and nerve stimulation. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1973 Oct 1;144(1):172–176. doi: 10.3181/00379727-144-37550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern S., Braun K. Effect of chemoreceptor stimulation on the pulmonary veins. Am J Physiol. 1966 Mar;210(3):535–539. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1966.210.3.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern S., Braun K. Pulmonary arterial and venous response to cooling: role of alpha-adrenergic receptors. Am J Physiol. 1970 Oct;219(4):982–985. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1970.219.4.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szidon J. P., Fishman A. P. Participation of pulmonary circulation in the defense reaction. Am J Physiol. 1971 Feb;220(2):364–370. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1971.220.2.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VON EULER U. S., LISHAJKO F. Catechol amines in the vascular wall. Acta Physiol Scand. 1958 Jun 2;42(3-4):333–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1958.tb01567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verity M. A., Bevan J. A. Fine structural study of the terminal effecror plexus, neuromuscular and intermuscular relationships in the pulmonary artery. J Anat. 1968 Jun;103(Pt 1):49–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]