Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text.

Keywords: coronary disease, diabetes mellitus, myocardial infarction, secondary prevention

Abstract

Background—

Vorapaxar reduces cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction (MI), or stroke in patients with previous MI while increasing bleeding. Patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) are at high risk of recurrent thrombotic events despite standard therapy and may derive particular benefit from antithrombotic therapies. The Thrombin Receptor Antagonist in Secondary Prevention of Atherothrombotic Ischemic Events-TIMI 50 trial was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of vorapaxar in patients with stable atherosclerosis.

Methods and Results—

We examined the efficacy of vorapaxar in patients with and without DM who qualified for the trial with a previous MI. Because vorapaxar is contraindicated in patients with a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack, the analysis (n=16 896) excluded such patients. The primary end point of cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke occurred more frequently in patients with DM than in patients without DM (rates in placebo group: 14.3% versus 7.6%; adjusted hazard ratio, 1.47; P<0.001). In patients with DM (n=3623), vorapaxar significantly reduced the primary end point (11.4% versus 14.3%; hazard ratio, 0.73 [95% confidence interval, 0.60–0.89]; P=0.002) with a number needed to treat to avoid 1 major cardiovascular event of 29. The incidence of moderate/severe bleeding was increased with vorapaxar in patients with DM (4.4% versus 2.6%; hazard ratio, 1.60 [95% confidence interval, 1.07–2.40]). However, net clinical outcome integrating these 2 end points (efficacy and safety) was improved with vorapaxar (hazard ratio, 0.79 [95% confidence interval, 0.67–0.93]).

Conclusions—

In patients with previous MI and DM, the addition of vorapaxar to standard therapy significantly reduced the risk of major vascular events with greater potential for absolute benefit in this group at high risk of recurrent ischemic events.

Clinical Trial Registration—

URL: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov. Unique identifier: NCT00526474.

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is an important risk factor for atherothrombosis.1 Despite advances in the treatment of both DM and cardiovascular disease, patients with DM are not only at increased risk for cardiovascular events but also have greater morbidity and mortality when such events occur.2,3 As the global population becomes more sedentary and obesity becomes more common, the prevalence of DM is increasing and is likely to continue to do so. As a result, the attributable risk for atherothrombotic events associated with DM is increasing.4

Editorial see p 1041

Clinical Perspective on p 1053

The association between DM and atherothrombosis is likely multifactorial.4 At least in part, enhanced platelet reactivity is believed to predispose patients with DM to thrombosis.5,6 Antithrombotic therapies, such as glycoprotein IIb/IIIa antagonists, enoxaparin, and prasugrel, have shown a consistent pattern of greater absolute and, in some cases, greater relative benefit in patients with DM compared with patients without this condition.7–10

Vorapaxar is a first-in-class protease-activated receptor-1 antagonist that potently inhibits thrombin-induced activation of platelets. Vorapaxar is effective for secondary prevention in patients with a history of atherosclerosis while increasing moderate or severe bleeding.10,11 Because of this tradeoff in potential benefit versus risk, it is of interest to identify patients, in particular among those with a history of myocardial infarction (MI), who may be appropriate candidates for treatment with vorapaxar.11 Therefore, in the present analysis, we examined the efficacy and safety of vorapaxar for secondary prevention of cardiovascular (CV) events in patients with and without DM who were enrolled in a large, randomized trial of vorapaxar versus placebo in the 2 weeks to 1 year after a qualifying MI.

Methods

Study Population

We have previously reported the design and results of the multinational, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of vorapaxar for secondary prevention of atherothrombosis (Thrombin Receptor Antagonist in Secondary Prevention of Atherothrombotic Ischemic Events-TIMI 50 [TRA 2°P-TIMI 50]).12,13 As reported previously, 17 779 patients qualified for the TRA 2°P-TIMI 50 trial on the basis of a history of MI within 2 weeks to 12 months and were randomly assigned to treatment with either vorapaxar sulfate 2.5 mg daily or placebo. Key exclusion criteria included a high risk of bleeding (history of a bleeding diathesis, recent active bleeding, or treatment with a vitamin K antagonist) or active hepatobiliary disease. Vorapaxar is approved for clinical use in the United States but is contraindicated in patients with a history of transient ischemic attack (TIA) or stroke. We therefore focused this analysis on the population of 16 896 patients with a history of a qualifying MI but without a history of stroke or TIA who are eligible for vorapaxar and relevant to clinical practice. Data for the broader population approved for clinical use in the United States (MI and peripheral arterial disease with no previous stroke or TIA) are provided (Tables I and II in the online-only Data Supplement).

The institutional review board or ethics committee for each participating institution trial reviewed and approved the trial. All of the patients gave written informed consent.

End Points

The primary end point for this analysis was the composite of CV death, MI, or stroke.13 The key secondary end point was the composite of the primary end point or recurrent ischemia leading to urgent revascularization. Bleeding was classified using the Global Utilization of Streptokinase and t-PA for Occluded Coronary Arteries (GUSTO) definition.14 A blinded clinical events committee adjudicated all elements of the primary and secondary efficacy end points, as well as all bleeding events in the trial.

Statistical Methods

A prespecified analysis was performed based on the patient’s history of DM as recorded by the local investigator at the time of random assignment. Comparisons of baseline characteristics between patients with and without DM were made using the χ2 test for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables. A Cox proportional hazard model was used for the efficacy analyses with the investigational treatment allocation and planned use of a thienopyridine as covariates. The interaction of DM with the randomized treatment was assessed in the overall US approval cohort with the addition of an interaction term (DM × treatment allocation) to the Cox proportional hazard model along with each of the main effects. Interaction P values <0.10 were considered evidence of a possible interaction. Kaplan-Meier 3-year cumulative event rates are presented with patients censored at the occurrence of an end point, death, or at the time of the last visit. Absolute risk differences and associated confidence intervals were generated using the risk reductions and confidence boundaries from the Cox model. Analyses of bleeding were performed in patients who received 1 or more doses of study drug. These analyses included all of the events that occurred from the first dose of study drug until 30 days after a final visit at the conclusion of the trial or 60 days after premature drug discontinuation.13

A Cox proportional hazard survival model was developed to describe the association between DM and the risk of CV death, MI, or stroke. Given the differences in patients with and without DM, the model included covariates that were thought to be potential confounders a priori (treatment allocation, age, sex, race, history of hypertension, history of hyperlipidemia, ongoing tobacco abuse, history of peripheral arterial disease, history of stroke or TIA, history of congestive heart failure, creatinine clearance <60 mL/min, weight <60 kg, and region). The proportional hazard assumption was tested using visual inspection of the Schoenfeld residuals. Analyses were performed with Stata version 12.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

Results

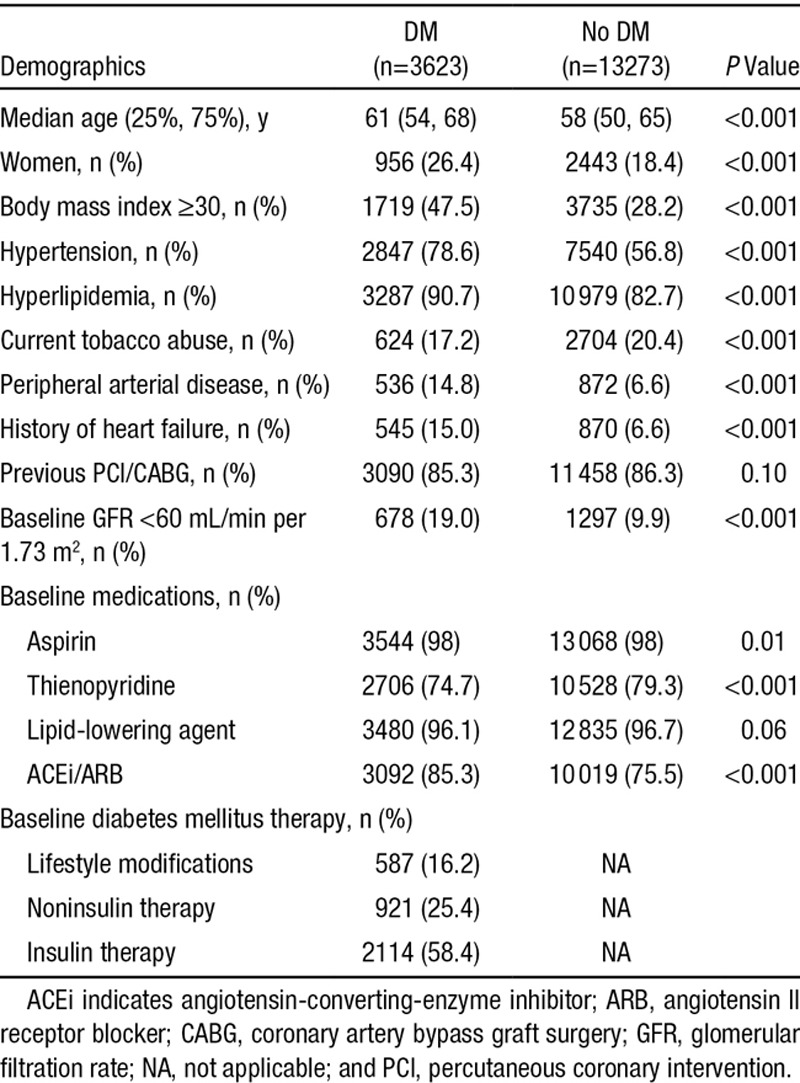

Among the 16 896 patients with a previous MI and no previous stroke or TIA randomly assigned to vorapaxar or placebo, 3623 (21%) had DM. Patients with DM were older, more often women, and were more likely to have hypertension, peripheral arterial disease, renal dysfunction, and obesity (Table 1). The majority (84%) of the patients with DM were being treated with either insulin or noninsulin therapies for hyperglycemia. Evidenced-based therapies for secondary prevention of atherothrombosis were used in a high proportion of both patients with and without DM (Table 1). The baseline characteristics in patients with and without DM stratified by treatment allocation were similar (Table III in the online-only Data Supplement).

Table 1.

Baseline Demographics Stratified by Diabetes Mellitus (DM) at Randomization

CV Outcomes and Bleeding in DM

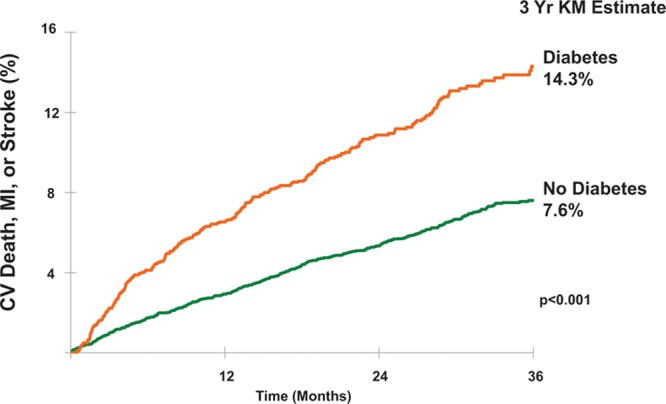

Among placebo-allocated patients, those with DM, when compared with those without, had nearly double the incidence of CV death, MI, or stroke at 3 years (14.3% versus 7.6%; P<0.001). After adjusting for potential confounders (treatment allocation, age, sex, race, history of hypertension, history of hyperlipidemia, ongoing tobacco abuse, history of peripheral arterial disease, history of stroke or TIA, history of congestive heart failure, creatinine clearance <60 mL/min, weight <60 kg, and region), DM was still associated with a 47% higher risk of CV death, MI, or stroke (adjusted hazard ratio [HRadj], 1.47 [95% confidence interval {CI}, 1.24–1.75]; P<0.001; Figure 1). Patients with DM were also at increased risk of the individual end points of CV death (4.4% versus 1.7%; HRadj, 1.58 [95% CI, 1.13–2.21]; P=0.008) and recurrent MI (10.2% versus 5.6%; HRadj, 1.46 [95% CI, 1.20–1.79]; P<0.001), with a trend toward a higher risk of stroke (2.5% versus 1.1%; HRadj, 1.54 [95% CI, 1.00–2.37]; P=0.051). The risk of GUSTO moderate/severe bleeding was similar in patients with and without DM (2.6% versus 1.9%; HRadj, 0.93 [95% CI, 0.63–1.38]; P=0.72).

Figure 1.

Incidence of cardiovascular (CV) death, myocardial infarction (MI), or stroke stratified by diabetes mellitus status (placebo group only). KM indicates Kaplan-Meier.

Efficacy and Safety of Vorapaxar

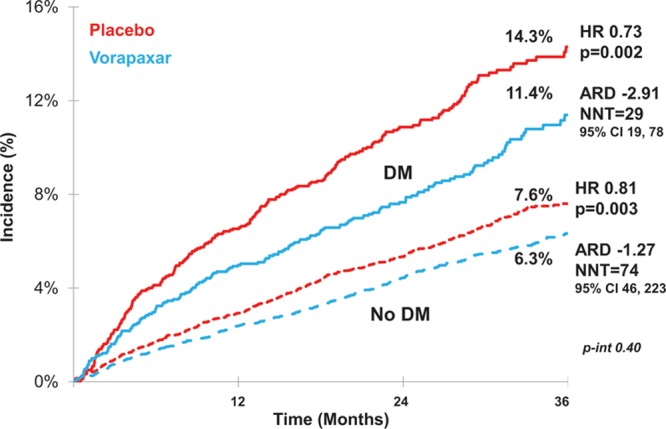

In patients with DM, treatment with vorapaxar reduced CV death, MI, or stroke at 3 years by 27% (hazard ratio [HR], 0.73 [95% CI, 0.60–0.89]; P=0.002; Figure 2). Similar effects were observed both in patients with DM treated with insulin (HR, 0.74 [95% CI, 0.53–1.02]) or without insulin (HR, 0.71 [95% CI, 0.56–0.92]; P for interaction=0.90). The relative effect of vorapaxar was similar among patients without DM (HR, 0.81 [95% CI, 0.71–0.93]; P=0.003; P for interaction=0.40). However, because the rate of major CV events was substantially higher in patients with DM, treatment with vorapaxar had a pattern of greater absolute risk reduction in patients with DM (absolute risk difference, –3.50% [95% CI, –1.28 to –5.36]) than without DM (absolute risk difference, –1.36% [95% CI, –0.45 to –2.15]). The calculated number needed to treat to avoid 1 major CV event over 3 years was 29 (95% CI, 19–78) among patients with DM and 74 (95% CI, 46–223) among those without DM.

Figure 2.

Incidence of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke with vorapaxar vs placebo stratified by diabetic status. ARD indicates absolute risk difference; HR, hazard ratio; and NNT, number needed to treat.

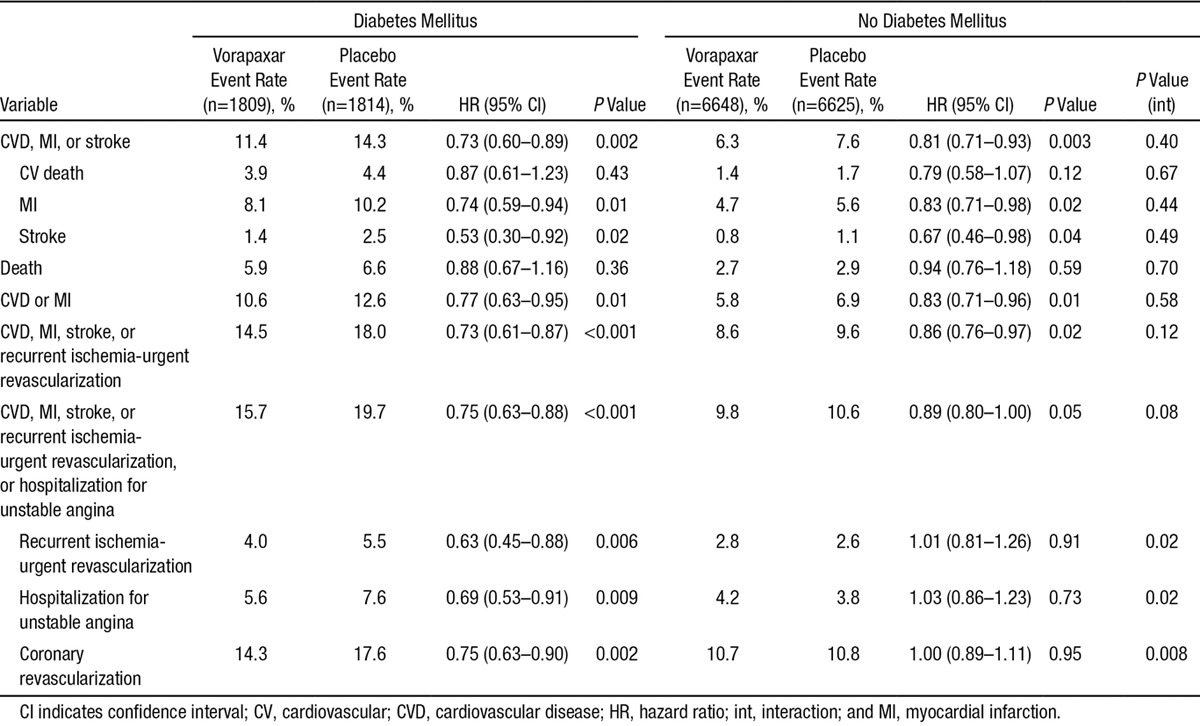

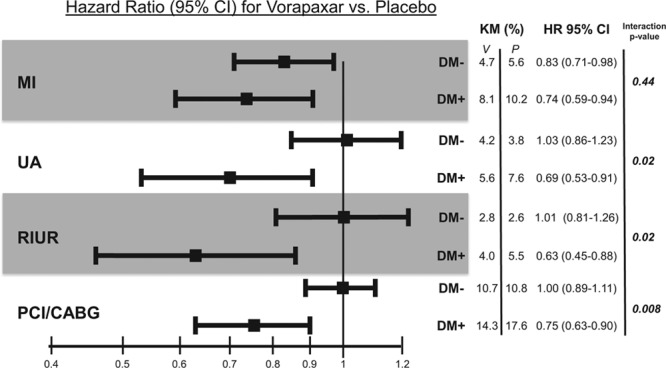

This pattern of a consistent relative risk reduction and greater absolute benefit in patients with DM was apparent across all components of the primary end point (Table 2). The relative effect of vorapaxar on ischemic end points was nominally greater in patients with than without DM, including recurrent ischemia leading to urgent revascularization (P for interaction=0.02) and coronary revascularization with either percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass graft surgery (P for interaction=0.008; Figure 3).

Table 2.

Efficacy of Vorapaxar in Patients With and Without Diabetes Mellitus

Figure 3.

Effects of vorapaxar on ischemic events stratified by diabetes mellitus (DM) status. CABG indicates coronary artery bypass graft surgery; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; KM, Kaplan–Meier; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; RIUR, recurrent ischemia leading to urgent revascularization; and UA, unstable angina.

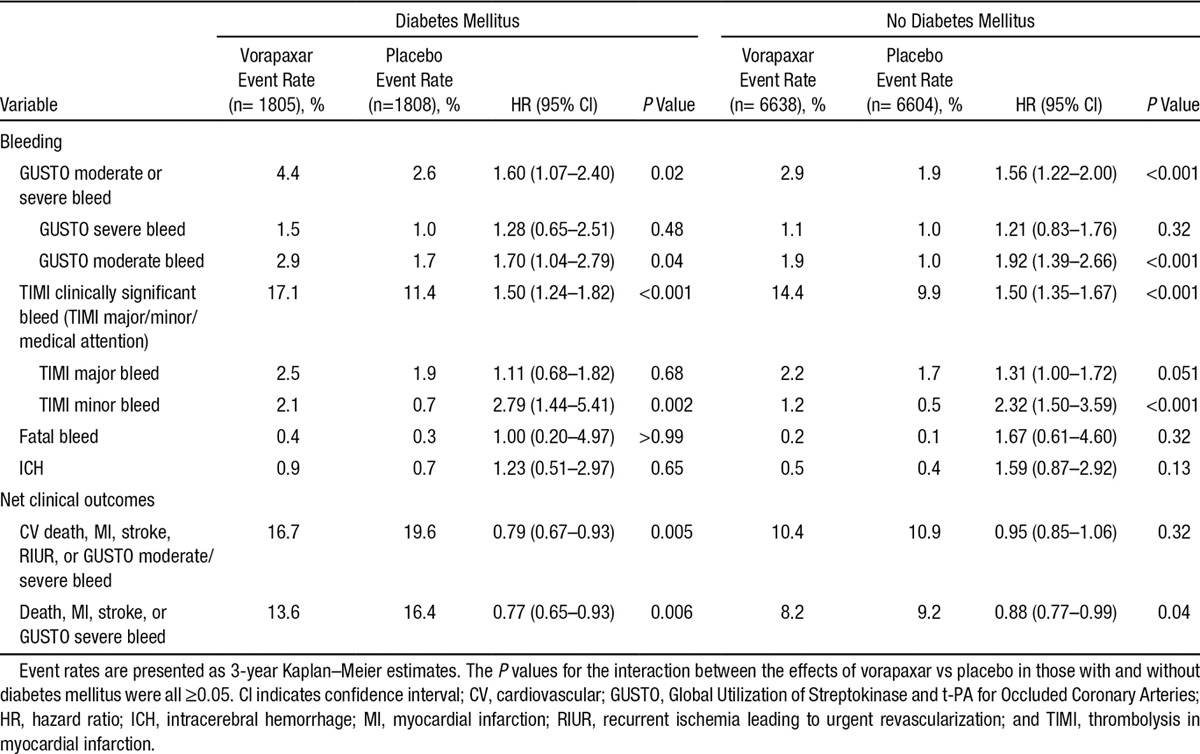

An increase in moderate or severe bleeding with vorapaxar in patients with DM (4.4% versus 2.6%; HR, 1.60 [95% CI, 1.07–2.40]) was similar to that for patients without DM (P for interaction=0.93; Table 3). Two prespecified composite end points of net clinical outcome were evaluated (Table 3). Among patients with DM, vorapaxar improved the net clinical outcome of CV death, MI, stroke, or recurrent ischemia leading to revascularization plus GUSTO moderate/severe bleeding (HR, 0.79 [95% CI, 0.67–0.93]; P=0.005), as well as the composite of death, MI, stroke, or GUSTO severe bleeding (HR, 0.77 [95% CI, 0.65–0.93]). Notably, the absolute risk difference for CV death, MI, stroke, recurrent ischemia requiring urgent revascularization, or GUSTO moderate/severe bleed in patients with DM was –3.89% (95% CI, –1.34 to –6.11) and in those without DM was –0.53% (95% CI, 0.61 to –1.57).

Table 3.

Bleeding and Net Clinical Outcomes in Patients With and Without Diabetes Mellitus

Discussion

Vorapaxar is a novel platelet inhibitor that is effective for the secondary prevention of atherothrombosis. As with other potent antiplatelet agents, its clinical use should take into account an individualized assessment of the potential antithrombotic benefits and risk of bleeding. Our findings from the TRA2°P-TIMI 50 trial showed a higher risk of recurrent major CV events in diabetic versus nondiabetic patients with established atherosclerosis despite standard medical therapy. When added to these standard therapies, treatment with vorapaxar reduced CV death, MI, or stroke in this high-risk group. Because of their higher cumulative risk, patients with DM had a potential greater absolute risk reduction than patients without DM, which translates into fewer patients needed to treat to prevent a major CV event (Figure 2).

DM and Secondary Prevention

Patients with established atherosclerosis who have DM have a high residual risk of recurrent events despite treatment with intensive medical therapy.15–18 This increased risk is related to the high prevalence of other risk factors in patients with DM (eg, hypertension and obesity), as well as the direct adverse pathological consequences of DM, including endothelial dysfunction, vascular inflammation, abnormal platelet reactivity, and decreased responsiveness to commonly used therapies.19 Notably, we found that, after adjusting for potential confounders, despite the use of aspirin in 98%, lipid-lowering agents in 97%, and renin-angiotensin pathway antagonists in 78%, patients with DM were still at 47% increased risk of major CV events. As the prevalence of DM increases, the secondary prevention of atherothrombosis will assume heightened importance in this high-risk group.

Vorapaxar and Secondary Prevention

In light of the increased reactivity of platelets that contributes to the adverse CV outcomes in patients with DM,6 this group of patients was identified at the initiation of TRA 2°P-TIMI 50 as a population of particular interest.6,18,20 We have shown previously that potent inhibition of the platelet P2Y12 receptor pathway with prasugrel in patients presenting with an acute coronary syndrome offers a greater benefit in patients with DM compared with nondiabetics.9 Similarly, patients with hemoglobin A1c ≥6% had evidence of a greater benefit from treatment with ticagrelor.18 Our data raise the possibility that vorapaxar, which inhibits platelets via a pathway separate from that of aspirin and P2Y12 inhibitors, similarly offers a particular advantage for patients with DM.

First, we found that there was a consistent reduction in major CV events with vorapaxar added to standard therapy among patients with DM. Second, because of their higher rate of recurrent CV events, patients with DM had a higher absolute risk reduction and a number needed to treat of 29 compared with 74 in patients without diabetes mellitus. Third, a nominal treatment interaction was observed such that, compared with patients without DM, patients with DM had a significantly greater relative reduction in hospitalization for unstable angina or coronary revascularizations. Although exploratory in nature, this observation that more potent antithrombotic therapy with vorapaxar provided a more pronounced reduction in ischemic events is consistent with what is known about the platelet pathobiology, as well as previous studies of antithrombotic agents in patients with DM (eg, patients treated with glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors at the time of acute coronary syndrome).7 In light of these findings, when weighing the risk of bleeding with the antithrombotic benefits of vorapaxar, patients with DM appear to be particularly appropriate candidates for consideration for treatment with this new therapy.

Limitations

These findings should be considered in the context of the limitations of the study. First, our observations are based on subgroups in the overall trial. However, this analysis was prespecified and the subgroups were large. Patients with DM can differ in the duration of the disease, degree of glycemic control, and presence of other medical comorbidities. Given the randomized nature of the study, these characteristics were likely balanced between the vorapaxar and placebo groups and thus not expected to influence the treatment comparison. However, it is possible that the magnitude of our observed effect may not apply to the entire spectrum of manifestations of DM. Second, the nominally significant interaction in the efficacy of vorapaxar with regard to ischemic end points should be regarded as hypothesis generating. Third, because the data were not captured in this trial, we are unable to perform additional exploratory analyses based on glycemic control or length of time in which patients have had DM.

Conclusions

Vorapaxar is an additional treatment option for long-term secondary prevention in patients with DM who have had a previous MI, in the absence of a previous stroke or TIA. DM is a high-risk indicator that identifies patients who appear to have a particularly favorable balance of antithrombotic efficacy and bleeding with vorapaxar.

Sources of Funding

The TRA2°P-TIMI 50 Trial was sponsored by Merck and Co.

Disclosures

The TIMI Study Group has received significant research grant support from Amgen, Astra-Zeneca, Athera, Beckman Coulter, BG Medicine, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Buhlmann Laboratories, Daiichi Sankyo, Eli Lilly and Co, Eisai, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson, Merck and Co, Nanosphere, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Ortho-Clinical Diagnostics, Pfizer, Randox, Roche Diagnostics, Sanofi-Aventis, Siemens, and Singulex. Dr Cavender reports consulting fees from AstraZeneca and Merck and Co. Dr Scirica reports consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Gilead, GE Healthcare, Lexicon, Arena, Eisai, St Jude’s Medical, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Forest Pharmaceuticals, Boston Clinical Research Institute, University of Calgary, Elsevier Practice Update Cardiology, and Forest Pharmaceuticals. Dr Bonaca was supported by a Research Career Development Award (K12 HL083786) from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and consulting fees for Merck and Co, AstraZeneca, Bayer, and Roche Diagnostics. Dr Angiolillo reports receiving payments as an individual for consulting fee or honorarium from Bristol Myers Squibb, Sanofi-Aventis, Eli Lilly, Daiichi-Sankyo, The Medicines Company, AstraZeneca, Merck and Co, Abbott Vascular, and PLx Pharma; participation in review activities from CeloNova, Johnson & Johnson, St Jude’s Medical, and Sunovion; and institutional payments for grants from Bristol Myers Squibb, Sanofi-Aventis, Glaxo Smith Kline, Eli Lilly, Daiichi-Sankyo, The Medicines Company, and AstraZeneca. Dr Dalby reports consulting fees and honoraria from Sanofi-Aventis, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Aspen. Dr Morais reports honoraria for lectures and consulting activities for Astra Zeneca, Boehringer Ingheleim, Bayer Healthcare, BMS/Pfizer, Lilly/Daiichi Sankyo, Jaba Recordati, and Merck, Sharp, and Dohme. Dr Oude Ophuis reports consultancy fees for Merck and Co. Dr Braunwald reports consulting fees/honoraria from Merck and Co (no compensation), Amorcyte, The Medicines Co, Medscape, Bayer, Daiichi Sankyo, and Menarini International. Dr Morrow reports consulting fees from BG Medicine, Eli Lilly, Gilead, Instrumentation Laboratory, Konica Minolta, Merck and Co, Novartis, Roche Diagnostics, and Servier. The other authors report no conflicts.

Footnotes

Guest Editor for this article was Emily B. Levitan, ScD.

The online-only Data Supplement is available with this article at http://circ.ahajournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.013774/-/DC1.

CLINICAL PERSPECTIVE

Vorapaxar is a first-in-class inhibitor of the platelet protease-activated receptor-1 pathway that is activated by thrombin. Vorapaxar is established to be effective for the secondary prevention of atherothrombosis and, like other potent antiplatelet agents, increases bleeding. The findings from this analysis of the TRA2°P-TIMI 50 show that, in high-risk patients with diabetes mellitus, the addition of vorapaxar to standard therapy significantly reduced the risk of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke with a favorable effect on net clinical outcomes. Although the relative benefit of vorapaxar was similar in patients with or without diabetes mellitus, there was a greater absolute risk reduction in cardiovascular events with vorapaxar in patients with diabetes mellitus such that only 29 patients needed to be treated to prevent one occurrence of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke over the period of follow-up (3 years). The use of vorapaxar in clinical practice should weigh the potential reductions in ischemic events with the concomitant risk of bleeding. These findings indicate that patients with diabetes mellitus have a particularly favorable balance between the risk of bleeding and reduction in thrombotic events with vorapaxar.

References

- 1.Bhatt DL, Eagle KA, Ohman EM, Hirsch AT, Goto S, Mahoney EM, Wilson PW, Alberts MJ, D’Agostino R, Liau CS, Mas JL, Röther J, Smith SC, Jr, Salette G, Contant CF, Massaro JM, Steg PG REACH Registry Investigators. Comparative determinants of 4-year cardiovascular event rates in stable outpatients at risk of or with atherothrombosis. JAMA. 2010;304:1350–1357. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1322. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donahoe SM, Stewart GC, McCabe CH, Mohanavelu S, Murphy SA, Cannon CP, Antman EM. Diabetes and mortality following acute coronary syndromes. JAMA. 2007;298:765–775. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.7.765. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.7.765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haffner SM, Lehto S, Rönnemaa T, Pyörälä K, Laakso M. Mortality from coronary heart disease in subjects with type 2 diabetes and in nondiabetic subjects with and without prior myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:229–234. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807233390404. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807233390404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fox CS, Coady S, Sorlie PD, D’Agostino RB, Sr, Pencina MJ, Vasan RS, Meigs JB, Levy D, Savage PJ. Increasing cardiovascular disease burden due to diabetes mellitus: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2007;115:1544–1550. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.658948. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.658948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sabatine MS, Braunwald E. Will diabetes save the platelet blockers? Circulation. 2001;104:2759–2761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferreiro JL, Angiolillo DJ. Diabetes and antiplatelet therapy in acute coronary syndrome. Circulation. 2011;123:798–813. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.913376. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.913376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhatt DL, Marso SP, Lincoff AM, Wolski KE, Ellis SG, Topol EJ. Abciximab reduces mortality in diabetics following percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:922–928. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00650-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roffi M, Chew DP, Mukherjee D, Bhatt DL, White JA, Heeschen C, Hamm CW, Moliterno DJ, Califf RM, White HD, Kleiman NS, Théroux P, Topol EJ. Platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors reduce mortality in diabetic patients with non-ST-segment-elevation acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2001;104:2767–2771. doi: 10.1161/hc4801.100029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wiviott SD, Braunwald E, Angiolillo DJ, Meisel S, Dalby AJ, Verheugt FW, Goodman SG, Corbalan R, Purdy DA, Murphy SA, McCabe CH, Antman EM TRITON-TIMI 38 Investigators. Greater clinical benefit of more intensive oral antiplatelet therapy with prasugrel in patients with diabetes mellitus in the trial to assess improvement in therapeutic outcomes by optimizing platelet inhibition with prasugrel-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 38. Circulation. 2008;118:1626–1636. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.791061. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.791061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morrow DA, Antman EM, Murphy SA, Qin J, Ruda M, Guneri S, Jacob AJ, Budaj A, Braunwald E TIMI Study Group. Effect of enoxaparin versus unfractionated heparin in diabetic patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction in the Enoxaparin and Thrombolysis Reperfusion for Acute Myocardial Infarction Treatment-Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction study 25 (ExTRACT-TIMI 25) trial. Am Heart J. 2007;154:1078–84, 1084.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.07.027. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scirica BM, Bonaca MP, Braunwald E, De Ferrari GM, Isaza D, Lewis BS, Mehrhof F, Merlini PA, Murphy SA, Sabatine MS, Tendera M, Van de Werf F, Wilcox R, Morrow DA TRA 2°P-TIMI 50 Steering Committee Investigators. Vorapaxar for secondary prevention of thrombotic events for patients with previous myocardial infarction: a prespecified subgroup analysis of the TRA 2°P-TIMI 50 trial. Lancet. 2012;380:1317–1324. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61269-0. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61269-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morrow DA, Scirica BM, Fox KA, Berman G, Strony J, Veltri E, Bonaca MP, Fish P, McCabe CH, Braunwald E TRA 2°P-TIMI 50 Investigators. Evaluation of a novel antiplatelet agent for secondary prevention in patients with a history of atherosclerotic disease: design and rationale for the Thrombin-Receptor Antagonist in Secondary Prevention of Atherothrombotic Ischemic Events (TRA 2°P)-TIMI 50 trial. Am Heart J. 2009;158:335–341.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.06.027. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morrow DA, Braunwald E, Bonaca MP, Ameriso SF, Dalby AJ, Fish MP, Fox KA, Lipka LJ, Liu X, Nicolau JC, Ophuis AJ, Paolasso E, Scirica BM, Spinar J, Theroux P, Wiviott SD, Strony J, Murphy SA TRA 2P–TIMI 50 Steering Committee and Investigators. Vorapaxar in the secondary prevention of atherothrombotic events. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1404–1413. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200933. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cavender MA, Rao SV, Ohman EM. Major bleeding: management and risk reduction in acute coronary syndromes. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2008;9:1869–1883. doi: 10.1517/14656566.9.11.1869. doi: 10.1517/14656566.9.11.1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mora S, Wenger NK, Demicco DA, Breazna A, Boekholdt SM, Arsenault BJ, Deedwania P, Kastelein JJ, Waters DD. Determinants of residual risk in secondary prevention patients treated with high- versus low-dose statin therapy: the Treating to New Targets (TNT) study. Circulation. 2012;125:1979–1987. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.088591. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.088591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cannon CP, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, Rader DJ, Rouleau JL, Belder R, Joyal SV, Hill KA, Pfeffer MA, Skene AM Pravastatin or Atorvastatin Evaluation and Infection Therapy-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 22 Investigators. Intensive versus moderate lipid lowering with statins after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1495–1504. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040583. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mehta SR, Yusuf S, Peters RJ, Bertrand ME, Lewis BS, Natarajan MK, Malmberg K, Rupprecht H, Zhao F, Chrolavicius S, Copland I, Fox KA Clopidogrel in Unstable angina to prevent Recurrent Events trial (CURE) Investigators. Effects of pretreatment with clopidogrel and aspirin followed by long-term therapy in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: the PCI-CURE study. Lancet. 2001;358:527–533. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)05701-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.James S, Angiolillo DJ, Cornel JH, Erlinge D, Husted S, Kontny F, Maya J, Nicolau JC, Spinar J, Storey RF, Stevens SR, Wallentin L PLATO Study Group. Ticagrelor vs. clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes and diabetes: a substudy from the PLATelet inhibition and patient Outcomes (PLATO) trial. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:3006–3016. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq325. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Angiolillo DJ, Jakubowski JA, Ferreiro JL, Tello-Montoliu A, Rollini F, Franchi F, Ueno M, Darlington A, Desai B, Moser BA, Sugidachi A, Guzman LA, Bass TA. Impaired responsiveness to the platelet P2Y12 receptor antagonist clopidogrel in patients with type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:1005–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.06.1170. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.06.1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Colwell JA, Nesto RW. The platelet in diabetes: focus on prevention of ischemic events. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:2181–2188. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.7.2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]