Apolipoprotein mimetic peptides have been shown to dramatically reduce atherosclerosis in animal models. Atherosclerosis is an example of an inflammatory disorder. Published studies of apolipoprotein mimetic peptides in models of inflammatory disorders other than atherosclerosis suggest that they may have efficacy in a wide range of inflammatory conditions.

ApoA-I as a Therapeutic Agent

Experiments in animal models of atherosclerosis (Badimon 1990, Plump 1994) and in preliminary human studies (Nissen 2003) make apolipoprotein A-I (apoA-I), which is the main protein in HDL, an attractive therapeutic target. The initial preliminary studies (Nissen 2003) suggested that therapeutic benefit might be achieved by administering weekly intravenous doses over a period of 5 – 6 weeks. However, subsequent larger clinical trials (Tardif 2007) suggest that longer periods of intravenous administration will be required for significant improvements to be achieved, making this an unlikely therapy for the millions of patients with atherosclerosis.

The Search for an Ideal apoA-I-Mimetic Peptide

The laboratories of Segrest and Anantharamaiah designed 18 amino acid peptides that did not have sequence homology with apoA–I but mimicked the class A amphipathic helixes contained in apoA–I (Anantharamaiah 1985, Venkatachalapathi 1993, Yancey 1995). They designed a peptide which they called 18A because it contained 18 amino acids and formed a class A amphipathic helix. When the amino terminus and the carboxy termini were blocked by addition of an acetyl group and amide group, respectively, stability and lipid binding properties were improved and the peptide was named 2F because of the two phenylalanine residues on the hydrophobic face. The 2F peptide mimicked many of the lipid binding properties of apoA-I but failed to alter lesions in a mouse model of atherosclerosis (Datta 2001). Using a human artery wall cell culture assay, a series of peptides were tested for their ability to inhibit LDL-induced monocyte chemotactic activity, which is primarily due to the production of monocyte chemoattractant-1 (MCP-1). A peptide (4F) with the same structure as 2F except for two additional phenylalanine residues on the hydrophobic face of the peptide (replacing two leucine residues) was found to be superior (Datta 2001).

Apolipoprotein Mimetic Peptides in Animal Models of Atherosclerosis

ApoA-I mimetic peptides dramatically reduced the development of atherosclerotic lesions in young mice (Navab 2002, Li 2004) and, when given with a statin, caused regression in old apoE null mice (Navab 2005a). We tested for synergy between pravastatin and D-4F by administering oral doses of each in combination that were predetermined to be ineffective when given as single agents. The combination significantly increased HDL-cholesterol levels, apoA-I levels, paraoxonase activity, rendered HDL antiinflammatory, significantly prevented lesion formation in young and caused regression of established lesions in old apoE null mice, ie, mice receiving the combination for 6 months had lesion areas that were smaller than those before the start of treatment (Navab 2005a). After 6 months of treatment with the combination, en face lesion area was 38% of that in mice maintained on chow alone with a significant 22% reduction in macrophage content in the remaining lesions, indicating an overall reduction in macrophages of 79%. The combination increased intestinal apoA-I synthesis by a significant 60%. In monkeys, the combination also rendered HDL antiinflammatory. These results (Navab 2005a) suggested that the combination of a statin and an HDL-based therapy might be a particularly potent anti atherosclerosis treatment strategy.

The benefit of apolipoprotein mimetic peptides in atherosclerosis was not limited to apoA-I mimetic peptides as, an apoJ mimetic peptide (Navab 2005b) and a peptide too small to form a helical structure (Navab 2005c) were also efficacious. The efficacy of these peptides was recently also demonstrated in a rabbit model of atherosclerosis (Van Lenten 2007).

Mechanism of Action of Apolipoprotein-Mimetic Peptides

The mechanism of action of the apolipoprotein mimetic peptides in atherosclerosis appears to relate to their ability to remove oxidized lipids from lipoproteins (Navab 2004, 2005d, Datta 2004), render HDL anti-inflammatory (Navab 2004, Navab 2005d) and promote reverse cholesterol transport from macrophages (Navab 2004; 2005d). Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory process that is mediated in part by the oxidation of phospholipids which induce vascular cells to express adhesion molecules, cytokines and pro-coagulant molecules (Berliner 2005, Gargalovic 2006). The mechanism of action of the apolipoprotein mimetic peptides seems to be related to their ability to bind and remove these pro-inflammatory oxidized lipids (Navab 2004, 2005d). As shown below, the apolipoprotein mimetic peptides are efficacious in models of vascular diseases that are not classified as atherosclerosis and in inflammatory processes that have an infectious etiology suggesting that oxidized lipids may be important mediators of a variety of inflammatory conditions other than atherosclerosis.

Apolipoprotein Mimetic Peptides in Models of Infection

Nasal infection of low density lipoprotein receptor null (LDLR−/−) mice with influenza A virus after the mice had been on a high-fat high-cholesterol (Western) diet resulted in viral pneumonia (Van Lenten 2002). Treatment of the mice with the apoA-I mimetic peptide D-4F (administered by intraperitoneal injection) significantly reduced the severity of the viral pneumonia. There was significantly less perivascular infiltration, pneumonia, and lymphoid hyperplasia in the mice treated with the peptide compared to those treated with vehicle without peptide. IL-6 levels in lung lysates and in plasma were dramatically less in the peptide treated mice compared to the controls. The control mice demonstrated a significant increase in plasma LDL-cholesterol levels and a dramatic decrease in HDL-cholesterol levels in during? the nine days following infection. Peptide treatment prevented the increase in LDL-cholesterol levels and actually resulted in a significant increase in HDL-cholesterol levels. The viral pneumonia was accompanied by a significant decrease in the activity of the HDL-associated enzyme paraoxonase (PON) in the control mice. Peptide treatment resulted in increased PON activity. After viral infection HDL taken from control mice was pro-inflammatory while the HDL from the peptide treated mice was anti-inflammatory. Macrophage trafficking into the innominate artery and the aorta were dramatically increased after viral infection in the control mice and peptide treatment completely prevented the increased movement of macrophages into the arteries. Viral titers in the lungs of the peptide treated mice were about half of those seen in the control mice. In vitro, the interaction of human monocytes with human T-cells resulted in increased production of IL-6. There was a dose dependent decrease in IL-6 levels with peptide treatment. Peptide treatment also resulted in a dose dependent decrease in granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) production which was not seen when the cells were treated with a scrambled peptide. While peptide treatment reduced the production of IL-6 and GM-CSF, it d OK dependently increased the production of IL-10 (Van Lenten 2002).

In a follow up study (Van Lenten 2004) human Type II pneumocytes were infected in vitro with influenza A virus. The viral infection caused a significant increase in the cellular content of phospholipids. There was also a significant increase in the cellular content of oxidized phospholipids that were derived from the increased parent non-oxidized phospholipids (e.g. both 1-palmitoyl–2-arachidonyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphorylcholine and oxidized products of 1-palmitoyl-2-arachidonyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphorylcholine increased following the viral infection). Treatment of the pneumocytes with an apoA-I mimetic peptide prevented the viral-induced increase in the oxidized products of the phospholipids but did not prevent the increase in non-oxidized phospholipids. Following viral infection and paralleling the increase in cellular phospholipid content there was a significant increase in the secretion of phospholipids from the cells. Peptide treatment significantly inhibited the increased secretion of oxidized phospholipids without altering the secretion of non-oxidized phospholipids. There was a time dependent increase in the production of interferon α and γ following viral infection that was significantly inhibited by peptide treatment. Similarly, there was a dramatic time dependent increase in the activation of caspase-3, caspase-8, and caspase-9 following viral infection that was significantly prevented by peptide treatment. Viral infection dramatically increased the release of IL-6 from the pneumocytes that was significantly lessened by peptide treatment. As little as 25 nanograms/mL of peptide significantly attenuated IL-6 secretion following viral infection. As was the case in vivo (Van Lenten 2002), in vitro viral titers were significantly reduced with peptide treatment (Van Lenten 2004). Thus, both in vitro and in vivo the apoA-I mimetic peptide D-4F significantly reduced the inflammatory response following infection with influenza A and reduced viral titers. These effects were correlated with a reduction in oxidized (but not non-oxidized) phospholipids that have been previously identified as being pro-inflammatory (Berliner 2005).

Treatment of human umbilical vein endothelial cells with bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) induced the adhesion of THP-1 monocytes (Gupta 2005). Incubation of the endothelial cells with the apoA-I mimetic peptide L-4F (L-4F is identical to D-4F except that it is synthesized from all L-amino acids instead of D-amino acids as is the case for D-4F) dose dependently reduced THP-1 adhesion. The reduction in LPS-induced monocyte adhesion was accompanied by a decreased expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule- (VCAM-1) and a significant reduction in the release of IL-6, IL-8, IFN-γ, TNFα, and MCP-1 into the culture media. The apoA-I mimetic peptide was shown to reduce the binding of LPS to the LPS binding protein which is required for interaction with cell surface receptors. The ability of L-4F to prevent the binding of LPS to its binding protein was shown to result from a physical interaction between the apoA-I mimetic peptide and LPS. The authors concluded that apoA-I mimetic peptides might be useful in the treatment of endotoxemia (Gupta 2005).

What are the ideal characteristics for an anti-inflammatory agent?

Oxidative stress is an important contributor to the inflammatory response (Fogelman 2005). Stocker and colleagues (Wu 2006, Stocker 2006) have suggested that the ideal agent should be both anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory; i.e. it should inhibit the pro-inflammatory response to oxidative stress but not inhibit the anti-oxidant response to the oxidative stress. Specifically, Stocker and colleagues (Wu 2006, Stocker 2006), have suggested that the ideal agent should inhibit oxidative stress-mediated inflammatory responses such as pro-inflammatory cytokine production while not inhibiting the induction of anti-oxidant enzyme systems such as heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1). It was recently demonstrated that HDL from healthy subjects meets these criteria for an ideal anti-inflammatory agent. HDL from healthy volunteers was shown to inhibit the induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines by human aortic endothelial cells exposed to oxidized phospholipids such as 1-palmitoyl-2-(5,6-epoxyisoprostane E2)-sn-glycero-3-phosphorylcholine (PEIPC) while not inhibiting the induction of HO-1 (Gharavi 2007). As shown below, apoA-I mimetic peptides appear to have similar characteristics.

Apolipoprotein mimetic peptides in models of diabetes

Abraham and colleagues made rats diabetic by administration of streptozotocin (Kruger 2005). The induction of diabetes was accompanied by a significant fall in aortic HO-1 (but not HO-2) levels and a significant fall in aortic extracellular superoxide dismutase (EC-SOD) levels without a fall in Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase levels. However if the rats were treated with the apoA-I mimetic peptide D-4F there was actually a significant increase in aortic HO-1 mRNA, protein and activity and a preservation of EC-SOD levels compared to the control non-diabetic rats. Consistent with the decrease in the aortic content of the anti-oxidant enzymes HO-1 and EC-SOD in the control diabetic rats there was a significant increase in aortic superoxide anion production, which was dramatically improved with peptide treatment. The induction of diabetes resulted in significant endothelial sloughing as measured by the presence of circulating endothelial cells and circulating endothelial cell fragments. Administration of the apoA-I mimetic peptide markedly reduced endothelial sloughing and preserved endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) mediated vascular reactivity (Kruger 2005).

In a follow up study Abraham and colleagues made rats diabetic by administration of streptozotocin resulting in blood glucose levels of 410 ± 35 mg/dL (Peterson 2007). The streptozotocin treated rats were given insulin to maintain blood glucose levels between 240 and 320 mg/dL to prevent ketosis and weight loss. Four groups of animals were studied: control, streptozotocin -insulin treated, streptozotocin-insulin treated plus D-4F, and rats treated with D-4F but without streptozotocin. In these studies D-4F had no effect on glucose levels. However, D-4F treatment significantly increased HO-1 activity in the heart and aorta of the diabetic rats without significantly changing HO-1 activity in the kidney or liver. The reduction of endothelial sloughing in the diabetic rats treated with D-4F seen in the previous study was confirmed in this longer study. One would predict that if D-4F treatment were actually decreasing endothelial sloughing as measured by the levels of circulating endothelial cells and endothelial cell fragments, D-4F treatment should also result in significantly increased CD31+ staining of the endothelium in the diabetic rats. This indeed was the case, CD31+ staining of the aorta was significantly reduced in the diabetic animals and was restored to control levels with D-4F treatment. Additionally, diabetes caused a significant decrease in aortic thrombomodulin expression that was restored to the levels of the control animals with D-4F treatment.

Diabetes resulted in a significant decrease in endothelial ?progenitor cell colony formation – in? marrow cultures from the diabetic rats that was restored almost to normal by D-4F treatment of the animals. In the endothelial progenitor cells cultured from the diabetic rats there was a significant reduction in HO-1 (but not HO-2) protein expression and a significant reduction in eNOS expression in the cells from the diabetic rats. D-4F treatment of the animals resulted in levels of HO-1 and eNOS in cultured endothelial progenitor cells equal to controls. Consistent with diabetes causing increased oxidative stress with loss of HO1, there was increased levels oxidized protein in sera from diabetic animals compared to D-4F treated and control animals (Peterson 2007).

Apolipoprotein mimetic peptides in a model of chronic rejection after heart transplantation

Using a transgenic approach it was shown that systemic rather than local (i.e. in the graft) HO-1 expression was more important in reducing cardiac allograft rejection in a mouse model of cardiac transplantation (Araujo 2003). Based in part on these observations (Arajuo 2003) and the reports by Abraham and colleagues that D-4F induced HO-1 expression in a rat model of diabetes (Kruger 2005, Peterson 2007), Ardehali and colleagues studied chronic rejection in a mouse model of heart transplantation in which B6.C-H2bm12 strain donor hearts were transplanted into wild-type C57BL/6 recipient mice (Schnickel 2006, Hsieh 2007). The transplanted mice were treated with vehicle or vehicle containing D-4F. The D-4F treated animals showed a dramatic reduction in cardiac allograft vasculopathy (p<0.009). Treatment with the apoA-I mimetic peptide also significantly reduced the number of graft-infiltrating CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes and CXCR3+ T-lymphocyte subsets. HO-1 mRNA was increased in the donor hearts after D-4F treatment, and HO-1 blockade partially reversed the beneficial effects of D-4F. In vitro studies revealed that D-4F reduced allogenic T-lymphocyte proliferation and effector cytokine production by HO-1 independent mechanisms. The authors concluded that this class of peptides with anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant properties provides a novel strategy for the treatment of cardiac allograft vasculopathy (Schnickel 2006, Hsieh 2007).

Apolipoprotein mimetic peptides in mouse models of hypercholesterolemia, sickle cell disease and scleroderma

Pritchard and colleagues reported that L-4F restored the balance between nitric oxide and superoxide anion production in LDL treated cultured endothelial cells (Ou 2003a). Both nitric oxide and superoxide anion are products of eNOS. LDL treatment of endothelial cells resulted in the production of more superoxide anion compared to the production of nitric oxide. L-4F treatment of LDL prior to presentation to the endothelial cells resulted in significantly more nitric oxide production by eNOS and significantly less production of superoxide anion compared to untreated LDL. By itself L-4F had no effect on superoxide anion production but it did increase nitric oxide production by the endothelial cells. Stimulation of the endothelial cells incubated with LDL decreased the association of heat shock protein 90 with eNOS. Pretreatment of LDL with L-4F prevented a decrease in heat shock protein 90 association with eNOS. The authors concluded that L-4F protects endothelial function by preventing LDL from uncoupling eNOS activity (Ou 2003a).

In a follow up studies, Pritchard and colleagues reported that LDLR−/− mice on a Western diet have impaired eNOS-dependent vasodilation which was normalized by treatment with L-4F (Ou 2003b) or D-4F even in the absence of apoA-I (Ou 2005). Treatment of endothelial cells in culture with 22(R)-hydroxycholesterol decreased nitric oxide production and increased superoxide anion production, increased ATP-binding cassette transporter-1 (ABCA1) and collagen expression. L-4F restored nitric oxide and superoxide anion balance, had little effect on ABCA1 expression, but significantly reduced the oxidized sterol-mediated increase in collagen expression. However, vessel wall thickness was reduced by D-4F treatment but only if the mice expressed apoA-I (Ou 2005).

The impairment of eNOS-dependent vasodilation was very severe in a mouse model of sickle cell disease and was dramatically improved with L-4F treatment. The sickle cell mice appeared lethargic and made little attempt to avoid handling. In contrast the sickle cell mice treated with L-4F became mobile and actively avoided handling similar to the normal control mice (Ou 2003b).

Pritchard and colleagues also studied tight-skin mice, which are a mouse model of scleroderma (Weihrauch 2007). Scleroderma is an autoimmune, connective tissue disorder that is characterized by impaired vascular function, increased oxidative stress, inflammation, and impaired angiogenesis. Tight skin mice have a defect in fibrillin-2, resulting in many of the myocardial and vascular features seen in scleroderma patients. The tight skin mice demonstrated impaired eNOS-mediated vasodilation that was significantly improved by treatment with D-4F. The tight skin mice had elevated levels of plasma triglycerides which were normalized with D-4F treatment. The hearts from the tight skin mice contained significantly higher levels of angiostatin and autoantibodies against oxidized phospholipids. D-4F treatment reduced angiostatin levels in the hearts of the tight skin mice and reduced the levels of autoantibodies against oxidized phospholipids by >50%. The authors concluded that apoA-I mimetic peptides might have promise in the treatment of vascular complications in patients with scleroderma (Weihrauch 2007).

Apolipoprotein mimetic peptides in a mouse model of brain arteriole inflammation and dementia

In large and medium sized arteries there are always a few macrophages in the subendothelial space even in perfectly normal vessels. These are thought to be sentinel macrophages that “patrol” the subendothelial space and remove cellular debris that accumulates from time to time. Atherosclerosis is a dramatic amplification of this process characterized by an influx of monocytes into the subendothelial space in response to the production of chemokines such as MCP-1. After entering the subendothelial space of these large and medium sized arteries the monocytes might? convert into macrophages and become foam cells. Arterioles are the smallest arterial vessels ranging in size from 10 to 100 μm in diameter. Unlike the case for large and medium sized arteries the sentinel macrophages associated with brain arterioles are found intimately associated with the adventitial aspect of the vessels. The macrophages associated with brain arterioles are referred to as microglia. On feeding LDLR−/− mice a Western diet there was a marked increase in microglia associated with brain arterioles (Buga 2006). Adding the apoA-I mimetic peptide D-4F to the drinking water of the mice on the Western diet dramatically reduced microglia association with brain arterioles to levels seen in wild-type and LDLR−/− mice on a low fat chow diet. The brain arterioles of the mice that received D-4F expressed significantly less of the pro-inflammatory chemokines MCP-1 and MIP-1α compared to mice on the Western diet that received the inactive control peptide scrambled D-4F. Consistent with the diffusible nature of MCP-1 and MIP-1α, the neuronal cells surrounding the brain arterioles of the mice on the Western diet receiving the inactive control scrambled peptide had significantly higher levels of MCP-1 and MIP-1α protein associated with them compared to mice receiving the active peptide D-4F. Neuronal cells are known to have surface receptors for MCP-1 and MIP-1α and one might expect that neuronal/brain function might change as a result of the increased association of these chemokines with these brain cells. Indeed, feeding the Western diet to the LDLR−/− l mice resulted in significantly impaired cognitive function in two different tests, the T-maze continuous alternation task and the Morris Water Maze test. Significant improvements of cognitive function was seen in both tests upon addition of the active peptide (but not the inactive control scrambled peptide) to the drinking water of the mice. Treatment with the apoA-I mimetic peptides did not significantly alter plasma lipids or lipoprotein levels and did not alter blood pressure. It was concluded that hyperlipidemia can induce brain arteriole inflammation resulting in increased levels of soluble chemokines that can diffuse from the vessels and interact with surrounding brain cells and cause cognitive impairment. It was also concluded that an apoA-I mimetic peptide could significantly reduce the inflammation of brain arterioles and significantly improve cognitive function in this mouse model (Buga 2006). In light of the fact that vascular dementia afflicts approximately 15% of Americans 65 years of age or older- second only to Alzheimer’s disease as the leading cause of dementia- and in the Medicare population has cost that are twice that of Alzheimer’s management in the Ambulatory settings (Hill 2005). Current shortcomings exist in effective outpatient management that could ultimately reduce morbidity and healthcare costs. As such, the novel activities of apoA-I mimetics in CNS arteriole and brain cell inflammation and performance in pre-clinical models could be important. Future clinical studies of apoA-I mimetics that would address the unmet needs in vascular medicine could thus be important and informative.

Conclusions

ApoA-I has been shown in animal models and humans to have therapeutic potential for reversing atherosclerosis. However, apoA-I itself is large and must be administered intravenously, making manufacture difficult and expensive. 4F is an apoA-I mimetic peptide that can be produced economically and it is currently undergoing clinical trials. On the basis of work in animals, 4F might have much the same therapeutic potential in humans as apoA-I. In the future other apoA-I mimetic peptides might become useful and some are already being investigated, such as trimeric apoA-I, and small peptides associated with HDL and apoA-I Milano, which is in advanced clinical development. ApoA-I mimetic 4F in addition to being anti atherogenic, it reduces the effect of proinflammatory molecules generated by oxidized lipids. In the present review the anti-inflammatory properties of apolipoprotein mimetic peptides has been demonstrated in a number of animal models other than atherosclerosis.

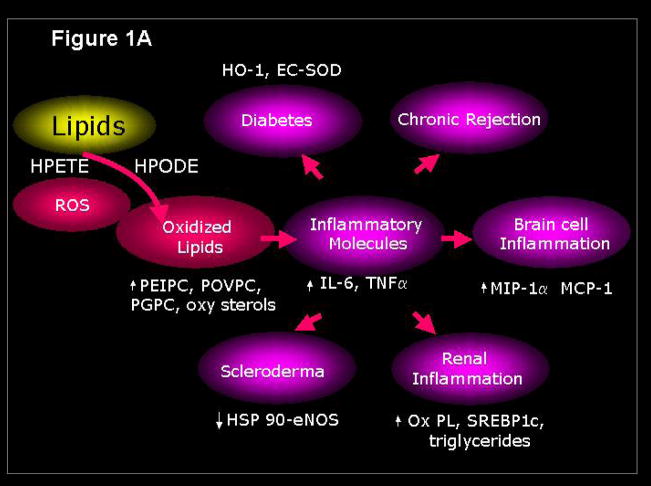

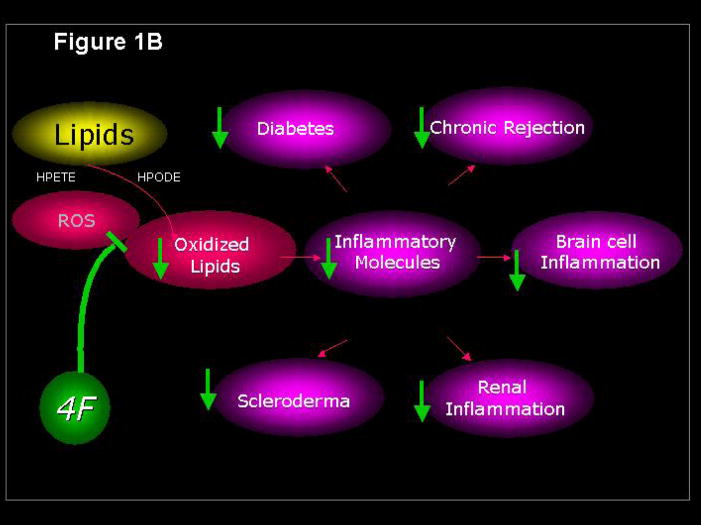

Figure 1.

Reactive oxygen species generate lipid mediators of inflammation (Figure 1A) that are inhibited by the apoA-I mimetic peptide 4F (Figure 1B). HPETE, hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid; HPODE, hydroperoxyoctadecadienoic acid; PEIPC, 1-palmitoyl–2-epoxyisoprostane-sn-glycero-3-phosphorylcholine; POVPC, 1-palmitoyl-2-oxovaleroyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphorylcholine; PGPC, 1-palmitoyl-2-glutaroyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphorylcholine; 4F, apoA-I mimetic peptide containing four phenylalanines.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by USPHS grants HL-30568 (AMF) and HL-34343 (GMA) and the Laubisch, Castera, and M.K. Grey Funds (AMF) at UCLA.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anantharamaiah GM, Jones JL, Brouillette CG, et al. Studies of synthetic peptide analogs of amphipathic helix I: Structure of peptide/DMPC complexes. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:10248–10255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo JA, Meng L, Tward AD, et al. Systemic rather than local heme oxygenase-1 overexpression improves cardiac allograft outcomes in a new transgenic mouse. J Immunol. 2003;171:1572–1580. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.3.1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badimon JJ, Badimon L, Fuster V. Regression of atherosclerotic lesions by high density lipoprotein plasma fraction in the cholesterol-fed rabbit. J Clin Invest. 1990;85:1234–1241. doi: 10.1172/JCI114558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berliner JA, Watson AD. A role for oxidized phospholipids in atherosclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:9–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp058118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buga GM, Frank JS, Mottino GA, et al. D-4F decreases brain arteriole inflammation and improves cognitive performance in LDL receptor-null mice on a Western diet. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:2148–2160. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600214-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta G, Chaddha M, Hama S, et al. Effects of increasing hydrophobicity on the physical-chemical and biological properties of a class A amphipathic helical peptide. J Lipid Res. 2001;42:1096–1104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogelman AM. When pouring water on the fire makes it burn brighter. Cell Metabolism. 2005;2:6–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gargalovic PS, Imura M, Zhang B, et al. Identification of inflammatory gene modules based on variations of human endothelial cell responses to oxidized lipids. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2006;103:12741–12746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605457103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gharavi NM, Gargalovic PS, Chang I, et al. High-density lipoprotein modulates oxidized phospholipid signaling in human endothelial cells from proinflammatory to anti-inflammatory. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:1346–1353. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.141283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta H, Dai L, Datta G, et al. Inhibition of lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory responses by an apolipoprotein AI mimetic peptide. Circ Res. 2005;97:236–243. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000176530.66400.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh GR, Schnickel GT, Garcia C, et al. Inflammation/oxidation in chronic rejection: apolipoprotein A-I mimetic peptide reduces chronic rejection of transplanted hearts. Transplantation. 2007;84:238–243. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000268509.60200.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill J, Fillit H, Shah SN, et al. Patterns of healthcare utilization and costs for vascular dementia in a community-dwelling population. J Alzheimer Dis. 2005;8:43–50. doi: 10.3233/jad-2005-8105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger AL, Peterson S, Turkseven S, et al. D-4F induces heme oxygenase-1 and extracellular superoxide dismutase, decreases endothelial cell sloughing, and improves vascular reactivity in rat model of diabetes. Circulation. 2005;111:3126–3134. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.517102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Chyu K-Y, Faria JR, et al. Differential effects of apolipoprotein A-I-mimetic peptide on evolving and established atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-null mice. Circulation. 2004;110:1701–1705. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000142857.79401.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navab M, Anantharamaiah GM, Hama S, et al. Oral administration of an apo A-I mimetic peptide synthesized from D-amino acids dramatically reduces atherosclerosis in mice independent of plasma cholesterol. Circulation. 2002;105:290–292. doi: 10.1161/hc0302.103711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navab M, Anantharamaiah GM, Reddy ST, et al. Oral D-4F causes formation of pre-β high-density lipoprotein and improves high-density lipoprotein-mediated cholesterol efflux and reverse cholesterol transport from macrophages in apolipoprotein E-null mice. Circulation. 2004;109:3215–3220. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000134275.90823.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navab M, Anantharamaiah GM, Hama S, et al. D-4F and statins synergize to render HDL anti-inflammatory in mice and monkeys and cause lesion regression in old apolipoprotein E-null mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005a;25:1426–1432. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000167412.98221.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navab M, Anantharamaiah GM, Reddy ST, et al. An oral apoJ peptide renders HDL anti-inflammatory in mice and monkeys and dramatically reduces atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-null mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005b;25:1932–1937. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000174589.70190.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navab M, Anantharamaiah GM, Reddy ST, et al. Oral small peptides render HDL anti-inflammatory in mice and monkeys and reduce atherosclerosis in apoE null mice. Circ Res. 2005c:524–532. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000181229.69508.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navab M, Anantharamaiah GM, Reddy ST, et al. Apolipoprotein A-I mimetic peptides. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005d;25:1325–1331. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000165694.39518.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nissen SE, Tsunoda T, Tuzcu EM, et al. Effect of recombinant apoA-I Milano on coronary atherosclerosis in patients with acute coronary syndromes: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290:2292–22300. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.17.2292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou Z, Ou J, Ackerman AW, et al. L-4F, an apolipoprotein A-1 mimetic, restores nitric oxide and superoxide anion balance in low-density lipoprotein-treated endothelial cells. Circulation. 2003a;107:1520–1524. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000061949.17174.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou J, Ou Z, Jones DW, et al. L-4F, an apolipoprotein A-1 mimetic, dramatically improves vasodilation in hypercholesterolemia and sickle cell disease. Circulation. 2003b;107:2337–2341. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000070589.61860.A9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou J, Wang J, Xu H, et al. Effects of D-4F on vasodilation and vessel wall thickness in hypercholesterolemic LDL receptor-null and LDL receptor/apolipoprotein A-I double knockout mice on Western diet. Circ Res. 2005;97:1190–1197. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000190634.60042.cb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson SJ, Husney D, Kruger AL, et al. Long-term treatment with the apolipoprotein A1 mimetic peptide increases antioxidants and vascular repair in type I diabetic rats. J Pharmacol Exp Therap. 2007;322:514–520. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.119479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plump AS, Scott CJ, Breslow JL. Human apolipoprotein A-I gene expression increases high density lipoprotein and suppresses atherosclerosis in the apolipoprotein E-deficient mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:9607–9611. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.20.9607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnickel GT, Hsieh GR, Kachikwu EL, et al. Cytoprotective gene HO-1 and chronic rejection in heart transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2006;38:3259–3262. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2006.10.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocker R, Perrella MA. Heme oxygenase-1: A novel drug target for atherosclerotic diseases? Circulation. 2006;114:2178–2189. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.598698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tardif JC, Gregoire J, L’Allier PL, et al. Effect of rHDL on atherosclerosis-safety and efficacy (ERASE) investigators. JAMA. 2007;297:1675–1682. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.15.jpc70004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Lenten BJ, Wagner AC, Anantharamaiah GM, et al. Influenza infection promotes macrophage traffic into arteries of mice that is prevented by D-4F, an apolipoprotein A-I mimetic peptide. Circulation. 2002;106:1127–1132. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000030182.35880.3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Lenten BJ, Wagner AC, Navab M, et al. D-4F, an apolipoprotein A-I mimetic peptide, inhibits the inflammatory response induced by influenza A infection of human type II pneumocytes. Circulation. 2004;110:3252–3258. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000147232.75456.B3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatachalapathi YV, Phillips MC, Epand RM, et al. Effect of end group blockage on the properties of a class A amphipathic helical peptide. Proteins Struct Funct Genet. 1993;15:349–359. doi: 10.1002/prot.340150403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Lenten BJ, Wagner AC, Navab M, et al. Lipoprotein inflammatory properties and serum amyloid A levels but not cholesterol levels predict lesion area in cholesterol-fed rabbits. J Lipid Res. 2007;48:2344–53. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700138-JLR200. Epub 2007 Aug 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weihrauch D, Xu H, Shi Y, et al. Effects of D-4F on vasodilation, oxidative stress, angiostatin, myocardial inflammation, and angiogenic potential in tight-skin mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H1432–H1441. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00038.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu BJ, Kathir K, Witting PK, et al. Antioxidants protect from atherosclerosis by a heme oxygenase-1 pathway that is independent of free radical scavenging. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1117–1127. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yancey PG, Bielicki JK, Lund-Katz S, et al. Efflux of cellular cholesterol and phospholipid to lipid-free apolipoproteins and class A amphipathic peptides. Biochemistry. 1995;34:7955–7965. doi: 10.1021/bi00024a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]