Dear. Editor,

A 17-year-old primigravida attended the service at the 31st gestational week for evaluation of monochorionic, monoamniotic twin gestation. First trimester sonographic images were not available. Morphological ultrasonography (US) demonstrated the fetuses joined at the level of their abdomen and pelvis, and presence of a diaphragmatic hernia in the second twin. The woman denied previous history of health problems or use of medicines and illicit drugs. Her 25-year-old husband was healthy, with negative history of consanguinity. No family history of genetic diseases and malformations was reported. Fetal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a dicephalus tetrabrachius-dipus conjoined twin. The fetus at right presented with a left diaphragmatic hernia containing stomach, small bowel and colon. The twins shared a single liver and a urinary bladder. Two kidneys connected each other at the level of their lower poles, and two vertebral spines were fused at the level of the sacrum (Figure 1). Echocardiography was normal.

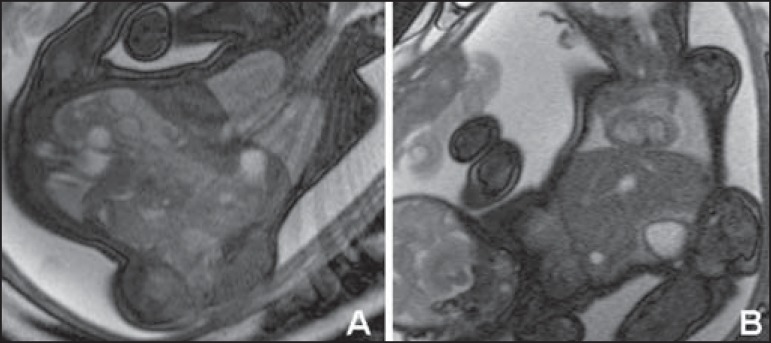

Figure 1.

Fetal MRI T2-weighted image showing the dicephalus tetrabrachiusdipus conjoined twin. The fetus at right presents with a left diaphragmatic hernia. Mediastinal structures (heart and large vessels) and pulmonary hypoplasia (A) are identified. Hepatic fusion is also visualized (B).

The conjoined twin was born by Cesarean section at the 35th gestational week, weighting 3,765 grams. Upper eyelid coloboma was found in the twin with diaphragmatic hernia. Radiographic evaluation demonstrated vertebral spines fusion at the level of the lumbar region, besides the presence of bowel loops in the thoracic cavity of the twin at right (Figure 2). Surgery for the diaphragmatic hernia could not be performed. The conjoined twin died at the 17th day of life.

Figure 2.

Postnatal image of the dicephalus tetrabrachius-dipus twin (A). Radiographic evaluation showing vertebral spines fusion at the L4 level and a single pelvis. A diaphragmatic hernia is observed in the fetus at right (there is evidence of the presence of bowel loops within the thoracic cavity), without identification of the heart and airways (B).

Imperfect twinning occurs in approximately one per 250,000 live births(1,2) and is classified according to the fusion site added by the term pagus(3). "Parapagus" twins (meaning "extensive lateral fusion") correspond to 28% of cases of conjoined twins(4). The subtype dicephalus tetrabrachius-dipus, as observed in the present case, is considered rare (4/10,000,000 births)(5).

US has shown to be the best method for initial evaluation of the gestation, and can identify imperfect twinning as early as at the 12th gestational week(1). However, US is subjected to limitations such as maternal biotype and presence of either oligohydramnios or anhydramnios. On the other hand, MRI represents a good complementary tool since it does not present such limitations, while providing images with better resolution(6). Additionally, it serves as support for a possible surgical planning, since it allows for visualization and detection of abnormalities which otherwise would be missed or inconclusive at US(2). In the present case, MRI was relevant, particularly in the determination of the type of imperfect twinning as well as of the extent of fusion and sharing of organs.

Congenital abnormalities not related to the fusion site are observed in 10% to 20% of cases of conjoined twins. Diaphragmatic hernia such as the one observed in the present case is one of the described findings(7). Upper eyelid coloboma that was also identified in the present case is considered to be a rare abnormality(8).

Thus, the correct determination of the type of imperfect twinning as well as of the fusion extent may be useful in the evaluation of the condition severity and in the postnatal surgical planning. Determining the severity of the condition is of paramount importance considering that the Brazilian laws allows for gestation termination in cases where the extrauterine life is not possible(3).

REFERENCES

- 1.McHugh K, Kiely EM, Spitz L. Imaging of conjoined twins. Pediatr Radiol. 2006;36:899–910. doi: 10.1007/s00247-006-0121-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denardin D, Telles JA, Betat RS, et al. Imperfect twinning: a clinical and ethical dilemma. Rev Paul Pediatr. 2013;31:384–391. doi: 10.1590/S0103-05822013000300017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nomura RM, Brizot ML, Liao AW, et al. Conjoined twins and legal authorization for abortion. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2011;57:205–210. doi: 10.1590/s0104-42302011000200020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spencer R. Theoretical and analytical embryology of conjoined twins: part I: embryogenesis. Clin Anat. 2000;13:36–53. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2353(2000)13:1<36::AID-CA5>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martínez-Frías ML, Bermejo E, Mendioroz J, et al. Epidemiological and clinical analysis of a consecutive series of conjoined twins in Spain. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44:811–820. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hibbeln JF, Shors SM, Byrd SE. MRI: is there a role in obstetrics? Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2012;55:352–366. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e3182487d04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mackenzie TC, Crombleholme TM, Johnson MP, et al. The natural history of prenatally diagnosed conjoined twins. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37:303–309. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2002.30830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mansour AM, Mansour N, Rosenberg HS. Ocular findings in conjoined (Siamese) twins. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1991;28:261–264. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-19910901-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]