Abstract

Vitamin D is well known for its role in promoting skeletal health. Vitamin D status is determined conventionally by circulating 25-dihydroxyvitamin D (25OHD) concentration. There is evidence indicating that circulating 25OHD concentration is affected by variation in Gc, the gene encoding the vitamin D binding protein (DBP). The composite genotype of two single nucleotide polymorphisms (rs7041 and rs4588) results in different DBP isotypes (Gc1f, Gc1s and Gc2). The protein configurational differences among DBP isotypes affect DBP substrate binding affinity.

The aims of this study were to determine 1) Gc variant frequencies in a population from an isolated rural region of The Gambia, West Africa (n = 3129) with year-round opportunity for cutaneous vitamin D synthesis and 2) the effects of Gc variants on 25OHD concentration (n = 237) in a genetically representative sub-group of children (mean (SD) age: 11.9 (4.8) years).

The distribution of Gc variants was Gc1f: 0.86, Gc1s: 0.11 and Gc2: 0.03. The mean (SD) concentration of 25OHD was 59.6 (12.9) nmol/L and was significantly higher in those homozygous for Gc1f compared to other Gc variants (60.7 (13.1) vs. 56.6 (12.1) nmol/L, P = 0.03). Plasma 25OHD and 1,25(OH)2D concentration was significantly associated with parathyroid hormone in Gc1f-1f but not in the other Gc variants combined.

This study demonstrates that different Gc variants are associated with different 25OHD concentrations in a rural Gambian population. Gc1f-1f, thought to have the highest affinity for 25OHD, had the highest 25OHD concentration compared with lower affinity Gc variants.

The considerable difference in Gc1f frequency observed in Gambians compared with other non-West African populations and associated differences in plasma 25OHD concentration, may have implications for the way in which vitamin D status should be interpreted across different ancestral groups.

Keywords: Vitamin D, Africa, DBP, Gc genotype, 25OHD

Highlights

-

•

We genotyped vitamin D binding protein (Gc) in 3129 rural Gambians.

-

•

GC variant distribution is Gc1f: 0.86, Gc1s: 0.11 and Gc2: 0.03.

-

•

25OHD concentrations are higher in Gc1f-1f compared to the other Gc variants.

Introduction

Vitamin D plays an essential role in maintaining skeletal health. Vitamin D status is typically determined by plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25OHD) concentration because it has a half-life of a couple of weeks, it is an integrated marker of different sources of vitamin D supply and it reflects the balance between supply and expenditure [1,2]. Unlike other vitamins, vitamin D is obtained both through the diet and through endogenous production from skin exposure to UVB. 25OHD status is therefore dependent on a number of non-dietary factors. These include skin pigmentation and skin exposure to UVB, i.e. factors associated with genetic, behavioural and environmental factors. Recent studies have highlighted the importance of genetic variation in vitamin D-regulating genes for vitamin D status [3,4]. Many studies have looked at multi-ethnic populations with diverse ancestry and have shown differences in 25OHD status depending on single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in vitamin D pathway-related genes. However, few studies have looked within a population, which is homogenous with respect to ancestry and to environmental influences relevant to vitamin D status.

Vitamin D binding protein (DBP) is encoded by Gc located on chromosome 4q11–q13 [5]. DBP is an albumin-like protein produced in the liver, which carries vitamin D metabolites in the circulation. DBP also has other physiological roles such as sequestering actin [6], binding fatty acids [7] and as a macrophage activating factor [8].

DBP transports vitamin D metabolites to tissues such as the liver and kidney. The major vitamin D metabolites (i.e. 25OHD and 1,25(OH)2D) are bound to DBP (> 95%) or another circulatory protein such as albumin, leaving only a small percentage circulating in its free form (for 25OHD (< 1%) [5,9,10]. Internalisation of DBP-bound 25OHD by the megalin/cubulin endocytic pathway in the proximal tubule epithelium allows for hydroxylation of 25OHD by 1-ɑ hydroxylase to produce 1,25(OH)2D, the active metabolite of vitamin D for systemic/endocrine functions [9]. It is thought that other tissues (non-renal) which do not express megalin rely largely on the diffusion of free 25OHD through the plasma membrane for subsequent conversion to 1,25(OH)2D for autocrine and paracrine effects. The biological relevance of the DBP-bound vitamin D metabolites versus the DBP-unbound or “free fraction” of vitamin D has not yet been established [9] and the role of DBP in the potential regulation of the free fraction is not fully understood.

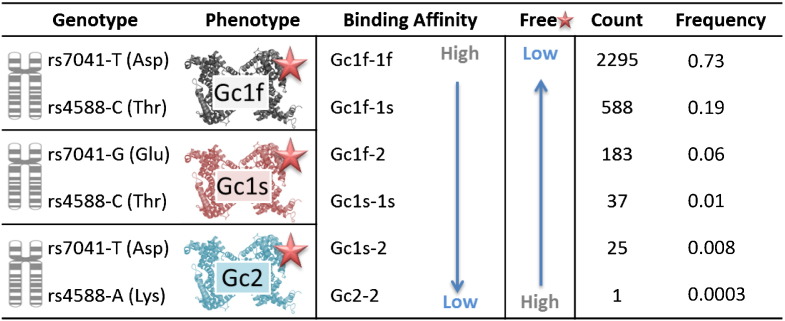

The three common Gc variants, described as Gc1f, Gc1s and Gc2 are determined by two SNPs in Gc; rs7041(Asp432Glu) and rs4588 (Thr436Lys). Combinations of these two SNPs give rise to six DBP isotypes (Gc1f-1f, Gc1f-1s, Gc1f-2, Gc1s-1s, Gc1s-2, Gc2-2). These isotypes have protein configurational differences which may in turn cause differences in the binding affinity of DBP for vitamin D metabolites (see Fig. 1) [9]. However, divergent results have been published that describe either very similar [11,12], or several-fold differences in affinity between 25(OH)D and DBP isoforms [13].

Fig. 1.

Gc composite genotypes; DBP isotype; DBP substrate binding affinities (i.e. vitamin D metabolites  ) and relative free fraction of

) and relative free fraction of  [5] and frequency of Gc variants in this Gambian study population (n = 3129).

[5] and frequency of Gc variants in this Gambian study population (n = 3129).

Gc1f-1f has the highest and Gc2-2 the lowest binding affinity for 25OHD and therefore different Gc variants may also influence the free fraction of 25OHD; the largest free fraction being associated with Gc2-2 and the smallest with Gc1f-1f isotype (see Fig. 1) [9].

The frequency of different DBP isotypes varies by ancestry; Gc1f-1f being most common in West Africans and African Americans and least common in Caucasians [14]. Thus, studies with participants of different ancestries cannot easily distinguish between the genetic versus environmental influences on vitamin D status.

The aim of this study was to determine the Gc variant frequencies in a sample of West-Africans (n = 3129) of predominantly Mandinka origin from the isolated rural West Kiang region of The Gambia using the Infinium HumanExome BeadChip. We investigated the association of variations in DBP isotype with vitamin D metabolites (25OHD and 1,25(OH)2D) and PTH concentration in a population of children from the same region (n = 237). This population has the opportunity for year-round endogenous vitamin D production and has a life-long low dietary calcium intake [15].

Materials & methods

Participants

The Gambia, West Africa, is a tropical country situated at latitude 13°N and has abundant sunshine, in 280–315 nm wavelength range, allowing for endogenous vitamin D production all year. The West Kiang province of The Gambia is a subsistence agricultural society where the majority of time is spent outside and customary dress does not restrict sunshine exposure to arms and face [16]. Samples and data for this study were available for West Kiang residents (collected in 2002–2003 and 2012-2014) as part of the MRC Keneba Biobank (http://www.ing.mrc.ac.uk/research_areas/the_keneba_biobank.aspx). All study participants were self-reported as being well at the time of recruitment (n = 3129; M = 1409). Ethical approval was given by The Gambian Government/MRC Unit Joint Ethics Committee and written informed consent was obtained from participants or their parents or guardians.

Sample collection and biochemical analysis

For a subset of children biochemical data, including plasma 25OHD concentrations, were available from previous studies (n = 237; M = 87; age 11.9 (SD 4.8) years) [17–19]. Briefly, overnight-fasted venous blood samples (5–15 mL) were collected and transferred into pre-cooled lithium heparin (LiHep) and EDTA-coated tubes. The blood was separated by centrifugation at 4 °C within 45 min of collection. The plasma and the plasma depleted cell pellets were frozen at − 80 °C and − 20 °C respectively and were later transported on dry ice to MRC Human Nutrition Research (HNR), Cambridge, for analysis and DNA extraction. 25OHD concentration (DiaSorin, UK; assay performance monitored by DEQAS http://www.deqas.org/), parathyroid hormone (PTH; Immulite, Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, UK; assay performance monitored by NEQAS http://www.ukneqas.org.uk), 1,25(OH)2D (IDS, UK also DEQAS), calcium, phosphate and albumin (Kone Analyser 20i, Finland) were measured. In a smaller number of participants (n = 172) fibroblast growth factor-23 (FGF23; C-terminal Immutopics Inc., CA, USA), total alkaline phosphatase (TALP) and creatinine (Cr) (Kone Analyser 20i, Finland) were also measured.

DNA extraction & genotyping

DNA was extracted from fresh or frozen plasma-depleted whole blood using standard methodology (QIAamp DNA kits, Qiagen, Manchester, UK; Nucleon Bacc2 DNA extraction kits, Scientific Laboratory Supplies Ltd, Nottingham, UK; or salting-out [20]). Samples (n = 3129) were then processed on the Infinium 240 k Human Exome Beadchip v1.0 and v1.1 (Illumina, CA, USA), which captures putative functional variation genome-wide. Genotypes were called using data-driven clustering (Genome Studio, Illumina, CA, USA).

The Exome Beadchip includes the two SNPs that determine DBP isotype, rs7041 and rs4588 [4,21], which were the focus of this study. The SNPs of interest were not in linkage disequilibrium (r2 = 0.004) as determined using genotype data on the whole sample (n = 3129) in Haploview using default criteria [22]. KING kinship analysis software [23] was used to estimate relatedness. This information was then used to generate family clusters based on 1st and 2nd degree relatives (i.e. 50% of genetic information shared (sibling) and 25% of genetic information shared (cousins)) and a family ID was allocated to each participant [23].

Statistical analysis

Biochemical analytes were compared between those homozygous for Gc1f-1f vs. other Gc variants (Gc1f-1s, Gc1s-1s, Gc1f-2, Gc1s-2 & Gc2-2) using DataDesk 6.3.1 (Data Description Inc, Ithaca, NY, USA) with Student's 2-sample t-tests. Data are reported as mean and standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed or geometric mean (+ 1SD, − 1SD) for negatively skewed data. Regression was used to identify relationships between vitamin D metabolites and PTH in univariate models unadjusted for age and sex, since their inclusion made no material difference to the results. Family groupings (family ID) were not significantly associated with 25OHD concentration and so was not adjusted for in any of the models. The inclusion of “study” as a covariate made no material difference to the DBP genotype effect on 25OHD concentration and so was not included in the analyses. The beta (β) coefficients of the ln-ln univariate regression analysis multiplied by 100 provide a sympercentage [24] which reflects the percentage change in the y variable based on one percentage change in the x variable. A DBP isotype group × variable interaction term was included to identify differences in the association between variables by DBP isotype group. P ≤ 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

DBP isotype/Gc variant distribution

The distribution of DBP isotype in the complete cohort (n = 3129) was Gc1f-1f: 73.3% (n = 2295), Gc1f-1s: 18.8% (n = 588), Gc1f-2: 5.8% (n = 183), Gc1s-1s: 1.2% (n = 37), Gc1s-2: 0.8% (n = 25) and Gc2-2: 0.03% (n = 1) (Fig. 1), which corresponds to Gc variants of Gc1f: 86.0%, Gc1s: 11.0% and Gc2: 3.0%.

The distribution of DBP isotypes was comparable in the subset with biochemistry (n = 237); Gc1f-1f: 73.8% (n = 175), Gc1f-1s: 20.7% (n = 49), Gc1f-2: 4.2% (n = 10), Gc1s-1s: 0.8% (n = 2). Gc1s-2: 0.4% (n = 1) and Gc2-2: 0% (n = 0). There were no differences in age or sex between DBP isotype groups (Gc1f-1f vs. other Gc variants together, Table 1).

Table 1.

Biochemistry by Gc variation; Gc1f-1f n = 175 vs. other: Gc1s-1f n = 49, Gc1s-1s n = 2, Gc2-1f n = 10, Gc2-1s n = 1, Gc2-2 n = 0. Data are mean (SD) apart from C-FGF23, PTH and 1,25(OH)2D which are geometric mean (− 1SD, + 1SD). P-value determined by unadjusted linear regression. Adjusting for age and sex made no material difference and so is not presented. Variables denoted with ⁎ were measured in a smaller sample set (n = 172).

| Variable | Gc1f-1f (n = 175) | Other (n = 62) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 12.1 (4.9) | 11.5 (4.9) | 0.4 |

| Sex (M/F) | 63/112 | 24/38 | 0.7 |

| 25OHD (nmol/L) | 60.7 (13.1) | 56.6 (12.1) | 0.03 |

| PTH (pg/mL) | 65.3 (39.6, 101.0) | 69.6 (44.2, 109.7) | 0.1 |

| 1,25(OH)2D (pmol/L) | 268.0 (196.0, 366.4) | 275.4 (206.8, 366.8) | 0.5 |

| C-FGF23 (RU/mL)⁎ | 267.7 (196.1, 366.4) | 275.4 (206.8, 366.8) | 0.1 |

| Phosphate (mmol/L) | 1.49 (0.23) | 1.52 (0.20) | 0.4 |

| Calcium (mmol/L) | 2.29 (0.14) | 2.30 (0.12) | 0.8 |

| Albumin (g/L)⁎ | 38.6 (3.4) | 38.7 (2.9) | 0.8 |

| Total alkaline phosphatase (U/L)⁎ | 312.4 (103.5) | 331.2 (103.7) | 0.3 |

| Creatinine (μmol/L)⁎ | 56.6 (8.9) | 55.9 (9.5) | 0.6 |

Bold data indicates statistical significance.

Biochemistry

The mean (SD) concentration of plasma 25OHD was 59.6 (12.9) nmol/L. The geometric mean (− 1SD, + 1SD) of PTH and 1,25(OH)2D were 64.9 (40.6, 103.5) pg/mL and 269.9 (198.8, 366.5) pmol/L respectively.

Biochemistry by Gc variation

25OHD concentration was higher in those homozygous for Gc1f (n = 175) compared to all other variants combined (n = 62) (25OHD: 60.7 (13.1) vs. 56.6 (12.1) nmol/L, P = 0.03) (Table 1). PTH tended to be lower in those homozygous for Gc1f compared to all other variants combined (PTH: 65.3 (39.6, 101.0) vs. 69.6 (44.2, 109.7) pg/mL, P = 0.10). 1,25(OH)2D was not different between Gc variant groups (1,25(OH)2D: 268.0 (196.0, 366.4) vs. 275.4 (206.8, 366.8) pmol/L, P = 0.5). There were no significant differences in other markers of bone mineral metabolism between Gc variant group.

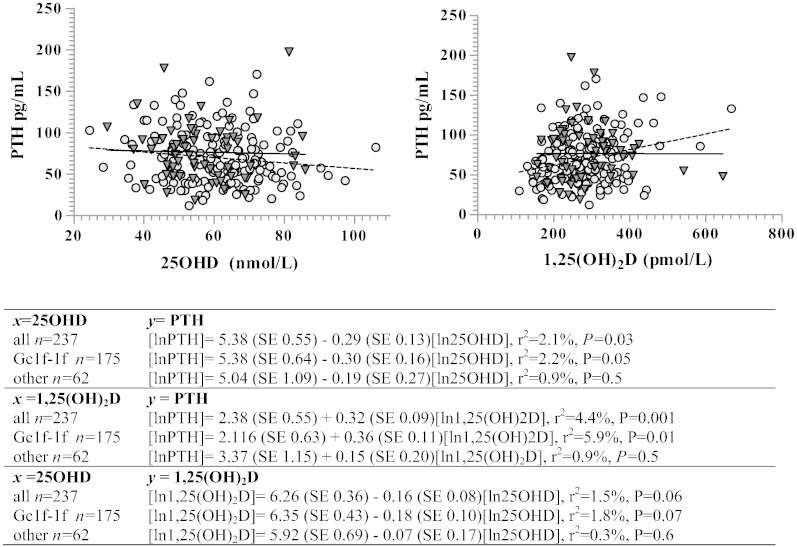

Correlations between vitamin D metabolites and PTH by Gc variation

In univariate models 25OHD was significantly negatively associated with PTH (beta coefficient (β) = − 29%, P = 0.03), 1,25(OH)2D significantly positively associated with PTH (β = 32%, P = 0.001) and 25OHD tended to be negatively associated with 1,25(OH)2D (β = −16%, P = 0.06) (Fig. 2). Gc1f homozygotes had significant associations between both 25OHD and 1,25(OH)2D with PTH whereas this was not seen in the other Gc variant groups (Fig. 2.) This Gc variant group difference was also reflected in the relationship between 25OHD and 1,25(OH)2D although this did not reach statistical significance. There were no significant Gc variant group × vitamin D metabolite interactions suggesting that the slopes were not statistically significantly different between variant groups.

Fig. 2.

Scatterplot of PTH and 25OHD and 1,25(OH)2D by Gc variant group: Gc1f-1f (n = 175) vs. other  (n = 62; Gc1s-1f, Gc1s-1s, Gc1f-2, Gc1s-2). Regression lines indicate the two different genotype groups (Gc1f-1f = broken line, other = solid line). Table indicates the equations of the lines for the association between 25OHD and 1,25(OH)2D with PTH and 25OHD with 1,25(OH)2D in all participants and divided into Gc variant group.

(n = 62; Gc1s-1f, Gc1s-1s, Gc1f-2, Gc1s-2). Regression lines indicate the two different genotype groups (Gc1f-1f = broken line, other = solid line). Table indicates the equations of the lines for the association between 25OHD and 1,25(OH)2D with PTH and 25OHD with 1,25(OH)2D in all participants and divided into Gc variant group.

Conclusions

To our knowledge this study reports the frequency of DBP isotypes in the largest cohort of rural West Africans (n = 3129) to date with frequencies of Gc1f 86.0%, Gc1s 11.0% and Gc2 3.0%.

This study adds to the body of evidence that Gc variation appears to influence vitamin D status [4] and may be associated with differences in plasma 1,25(OH)2D and PTH, potentially reflecting differences in the association between vitamin D metabolites and PTH by DBP isotypes. Gc1f homozygotes, suggested to have the highest affinity for 25OHD, had the highest plasma 25OHD concentration compared with the lower affinity DBP isotypes. There was a tendency for PTH to be lower in Gc1f homozygotes and the relationship between PTH and 25OHD or 1,25(OH)2D was stronger in Gc1f homozygotes than in other Gc variants.

These findings suggest that DBP isotype may influence vitamin D metabolism through multiple pathways. We speculate that this may be associated with a) differences in plasma 25OHD directly suppressing PTH production and secretion in the parathyroid gland [25] and/or b) differences in the free fraction of 25OHD which may modulate the availability for renal hydroxylation into 1,25(OH)2D which in turn suppresses PTH through the calcium-PTH-1,25(OH)2D axis. However, the renal internalisation of 25OHD has been reported to be dependent on the megalin/cubulin pathway [9] and may be independent of the free fraction of 25OHD. The influence of DBP isotype on free 25OHD needs further investigation.

A strength of this study is that the participants were subject to relatively uniform environmental exposures and all participants were rural Gambian of predominantly Mandinka ancestry with a dark skin type. Although we did not monitor skin exposure to the sun we anticipate that skin exposure allowing for endogenous vitamin D synthesis is likely to have been similar among participants due to similar day to day outdoor activities in year-round tropical sunshine and similar cultural dress. Similarly, previous studies in the region have demonstrated consistently low dietary calcium intakes in otherwise healthy rural Gambian children and we do not anticipate that dietary habits were different among the study participants. Other studies which have looked at differences between different Gc genotypes may have been confounded by other genetic factors (e.g. influencing skin type), ethnicity, environmental factors, particularly UVB exposure, lifestyle and different dietary habits that may have influenced plasma 25OHD and PTH concentrations. An analytical limitation of the study is the uneven group sizes of different DBP isotypes in our sample. An additional limitation is the small number of biochemical markers available for analysis. Analytes such as DBP concentration, free 25OHD, albumin and calculated free 25OHD would have provided some additional mechanistic insight into the role of DBP genotype on vitamin D metabolism and these should be included in future studies. These small but significant DBP isotype-dependent difference in 25OHD concentration, and subsequent effects on PTH may have a longer term implications on bone and other health outcomes.

In conclusion, this study shows that in a population with a relatively high vitamin D status, differences in 25OHD concentration are present between carriers of different DBP isotypes. This may have implications for the way in which circulating 25OHD concentration is interpreted across groups differing in predominant DBP isotypes.

Funding sources

This research was jointly funded by the MRC & the Department for International Development (DFID) under the MRC/DFID Concordat agreement. MRC programmes: U105960371, U123261351 & MC-A760-5QX00

Conflicts of interest

All authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We should like to thank all of the participants; the staff at MRC Keneba; the laboratory staff at MRC HNR; Ms K Pearce at the Core Genomics of the Institute of Child Health, UCL; our colleagues of the Mal-ED consortium at the Centre for Public Health Genomic, University of Virginia, USA, in particular Drs J Mychaleckyj and U Nayak, University of Virginia; and Prof AM Prentice, MRC ING. Dr VS Braithwaite would like to thank Corpus Christi College Cambridge, UK for their support.

References

- 1.Jones K.S. 25(OH)D2 half-life is shorter than 25(OH)D3 half-life and is influenced by DBP concentration and genotype. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(9):3373–3381. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-1714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones K.S. Plasma appearance and disappearance of an oral dose of 25-hydroxyvitamin D2 in healthy adults. Br J Nutr. 2012;107(8):1128–1137. doi: 10.1017/S0007114511004132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang T.J. Common genetic determinants of vitamin D insufficiency: a genome-wide association study. Lancet. 2010;376(9736):180–188. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60588-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moy K.A. Genome-wide association study of circulating vitamin D-binding protein. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99(6):1424–1431. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.080309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooke N.E. Direct regional assignment of the gene for vitamin D binding protein (Gc-globulin) to human chromosome 4q11–q13 and identification of an associated DNA polymorphism. Hum Genet. 1986;73(3):225–229. doi: 10.1007/BF00401232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanger J.M. Disruption of microfilament organization in living nonmuscle cells by microinjection of plasma vitamin D-binding protein or DNase I. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87(14):5474–5478. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.14.5474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bouillon R. The vitamin D binding protein DBP. In: Feldman D., Pike J.W., Adams J.S., editors. Vitamin D. Academic Press; 2011. pp. 57–72. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamamoto N., Naraparaju V.R. Role of vitamin D3-binding protein in activation of mouse macrophages. J Immunol. 1996;157(4):1744–1749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chun R.F. Vitamin D and DBP: the free hormone hypothesis revisited. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2013;144:132–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2013.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bikle D.D. Assessment of the free fraction of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in serum and its regulation by albumin and the vitamin D-binding protein. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1986;63(4):954–959. doi: 10.1210/jcem-63-4-954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bouillon R., van Baelen H., de Moor P. Comparative study of the affinity of the serum vitamin D-binding protein. J Steroid Biochem. 1980;13(9):1029–1034. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(80)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boutin B., Galbraith R.M., Arnaud P. Comparative affinity of the major genetic variants of human group-specific component (vitamin D-binding protein) for 25-(OH) vitamin D. J Steroid Biochem. 1989;32(1A):59–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(89)90014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arnaud J., Constans J. Affinity differences for vitamin D metabolites associated with the genetic isoforms of the human serum carrier protein (DBP) Hum Genet. 1993;92(2):183–188. doi: 10.1007/BF00219689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kamboh M.I., Ferrell R.E. Ethnic variation in vitamin D-binding protein (GC): a review of isoelectric focusing studies in human populations. Hum Genet. 1986;72(4):281–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00290950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Braithwaite V. Follow-up study of Gambian children with rickets-like bone deformities and elevated plasma FGF23: possible aetiological factors. Bone. 2012;50(1):218–225. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prentice A. Maternal plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration and birthweight, growth and bone mineral accretion of Gambian infants. Acta Paediatr. 2009;98(8):1360–1362. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01352.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braithwaite V. Iron status and fibroblast growth factor-23 in Gambian children. Bone. 2012;50:1351–1356. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jarjou L.M.A. Randomized, placebo-controlled, calcium supplementation study in pregnant Gambian women: effects on breast-milk calcium concentrations and infant birth weight, growth, and bone mineral accretion in the first year of life1–3. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:657–666. doi: 10.1093/ajcn.83.3.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hawkesworth S. Dietary supplementation of rural Gambian women during pregnancy does not affect body composition in offspring at 11–17 years of age1,2. J Nutr. 2008;138:2468–2473. doi: 10.3945/jn.108.098665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller S.A., Dykes D.D., HF. P. A simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16(1215) doi: 10.1093/nar/16.3.1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hirschfeld J. A simple method of determining haptoglobin groups in human sera by means of agar-gel electrophoresis. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1959;47:169–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1959.tb04845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gabriel S.B. The structure of haplotype blocks in the human genome. Science. 2002;296(5576):2225–2229. doi: 10.1126/science.1069424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manichaikul A. Robust relationship inference in genome-wide association studies. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(22):2867–2873. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cole T.J. Sympercent: symmetric percentage differences on the 100 loge scale simplify the presentation of log transformed data. Stat Med. 2000;19:3109–3125. doi: 10.1002/1097-0258(20001130)19:22<3109::aid-sim558>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adams J.S. Redefining human vitamin D sufficiency: back to the basics. Bone Res. 2013;1(1):2–10. doi: 10.4248/BR201301002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]