Abstract

Real-time imaging coupled with a permeabilized cell system presents a very versatile platform to visualize the dynamic and intricate nature of nuclear envelope breakdown, one of the major morphological changes of mitosis. Here, we describe such a strategy in which the plasma membrane of cells expressing fluorescently tagged nucleoporin POM121 and Histone H2B is permeabilized with digitonin. These cells are then incubated with mitotic Xenopus egg extract to create conditions that recapitulate the major events of mitotic nuclear remodeling seen in live-cell imaging, providing the opportunity to probe mechanisms and pathways that coordinate nuclear disassembly.

Keywords: Permeabilized cells, Live-imaging, Nuclear envelope, Xenopus egg extracts, GFP, POM121, Histone 2B mCherry

1. Introduction

Nuclear envelope breakdown at mitosis involves the coordination of many events, including dispersal of nuclear pore complexes, disassembly of the nuclear lamina, and global remodeling of nuclear membranes (1, 2). The rapid nature of these processes makes them difficult to capture and interpret in static images, although important clues have come from analysis of fixed samples examined by light and electron microscopy (3–6). More recently, experimental systems amenable to tracking dynamics of these events have pushed our knowledge further forward (7–10). In some cases, the experimental system has been the Xenopus egg extract, in which mitosis can be triggered in a very synchronous manner, allowing nuclear envelope breakdown to be assessed at specific time points. A main advantage of this cell-free system is its accessibility to biochemical manipulation. The addition of antibodies, interfering protein fragments, and small molecule inhibitors can be used to acutely block a particular pathway in order to probe its contribution. Another major strategy has been time-lapse imaging of intact cells that express a marker protein fused with green fluorescent protein or other variant. This approach has the advantage of yielding rich spatiotemporal information about the dynamics of specific events being tracked. Such a live-imaging experiment is shown in Fig. 1, which illustrates the rapid and dramatic nature of nuclear membrane rearrangements at the prophase to prometaphase transition.

Fig. 1.

Live-imaging of nuclear envelope breakdown in intact cells. HeLa cells stably expressing POM121-3GFP were plated on a chambered cover glass slide. After ~16 h, the DMEM medium was aspirated and replaced with DMEM-F12 (which is buffered with HEPES and lacks phenol red) and the chamber was set up for live-imaging on a heated (37°C) automated microscope stage. DNA was visualized by adding DAPI, a cell permeable DNA dye, to the culture medium. Nuclear membrane remodeling and DNA condensation, two key features of early mitosis, were tracked to assess progression from interphase to prometaphase. Images were acquired using a ×60 objective in 3 min intervals. Scale bar, 10 μM.

As with all techniques there are caveats to keep in mind. In cell-free systems, there is the possibility that cellular processes are not perfectly recapitulated, although the Xenopus egg extract system has been a reliable and rich source for discovery of fundamental mechanisms involved in cell cycle, DNA replication, nuclear transport, and more (11–14). When intact cells express a tagged protein, it is possible that the tag or the expression level alters the function of that protein or its environment. Certainly in the case of proteins targeted to the nuclear envelope, this latter point must be kept in mind as the over-expression of such proteins can lead to proliferation and deformation of the nuclear membranes (15, 16). When stable lines are selected, it is important to choose ones that do not have distortions in nuclear contour (Fig. 1). Overall, however, both cell-free and live-imaging approaches have been very useful in providing insight into mitotic remodeling of the nucleus.

To learn more about how nuclear envelope breakdown is executed and regulated, we and others have been interested in combining the advantages of real-time cell-based imaging with the experimental manipulation possible in a cell-free system. Kutay and colleagues pioneered such a combined strategy to study the role of the small GTPase Ran in nuclear disassembly (7). To do so, they permeabilized the plasma membrane of cells expressing the inner nuclear membrane protein LAP2β fused to GFP and added mitotic (cytostatic factor arrested) Xenopus egg extract to induce nuclear envelope breakdown. In conjunction, they added fluorescently labeled dextran to track changes in nuclear permeability. Here, we detail a similar strategy, with some important differences (Fig. 2). Namely, we use a cell line expressing POM121-3GFP and histone H2B-mCherry, as this allows visualization of a marker of the nuclear pore complex itself during disassembly and simultaneously provides information on chromatin condensation, which confirms the presence of proper mitotic signaling. We also mix interphase and mitotic extracts to adjust the potency of the mitotic trigger, as slowing the process enables detailed changes of nuclear membrane dispersal to be studied.

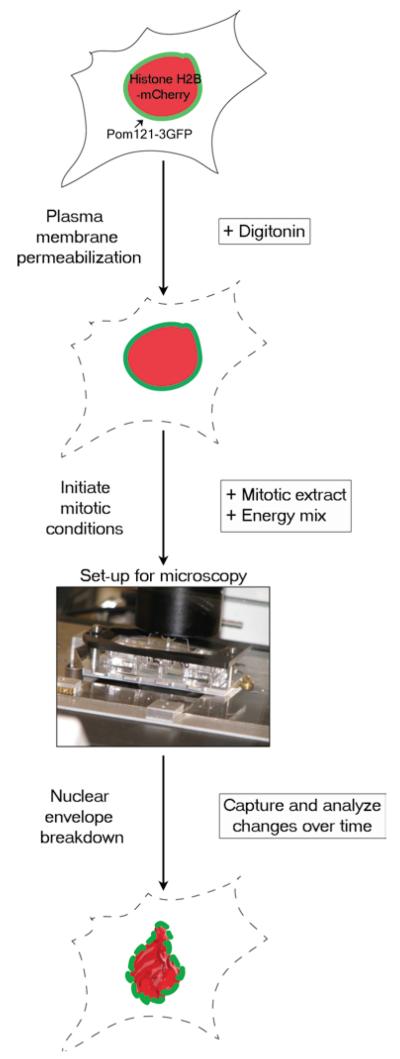

Fig. 2.

Experimental set-up for real-time nuclear envelope breakdown assay.HeLa cells stably expressing POM121-3GFP (green) and HistoneH2B-mCherry (red) are plated and allowed to grow on a chambered cover glass slide for 16–24 h (see Subheading 3.1). The cells are then treated with digitonin, which preferentially permeabilizes the plasma membrane, leaving the nuclear membrane intact (see Subheading 3.3). To initiate mitotic conditions, Xenopus mitotic extract and energy mix (see Subheading 3.2) are added to the permeabilized cells. The chambered cover glass slide is then placed in a slide holder and imaged as described in Subheading 3.4. As mitosis progresses, the mCherry-labeled chromatin condenses and POM121-3GFP tracks nuclear membrane remodeling.

2. Materials

All solutions are prepared using autoclaved double-distilled or filtered water. All stock solutions except autoclaved 1 M sucrose are prepared and stored at room temperature. Working solutions are pre-mixed and stored temporarily at 4°C.

2.1. Solutions for Xenopus Egg Extract Preparation

Egg lysis buffer (ELB): 2.5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl, 10 mM HEPES, 250 mM sucrose. Autoclave and adjust pH to 7.6.

Mitotic buffer: 240 mM β-glycerophosphate, 60 mM EGTA, 45 mM MgCl, 1 mM DTT, pH 7.3.

1× MMR: 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4, 2 mM CaCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.8.

2% cysteine—make fresh, dissolve in water, pH to 7.8–8.0 with NaOH. 10 mg/mL cycloheximide stock stored at 4°C (can be used for a few days).

1 M DTT dissolved in DMSO, stored at −20°C; 5 mg/mL cytochalasin B, stored at −20°C; 5 mg/mL aprotinin and leupeptin stocks, stored at −80°C.

2.2. Cell Culture and Preparation

HeLa cell lines stably expressing POM121-3GFP and Histone H2B, cultured under standard conditions (DMEM, 10% FBS, and antibiotics used to maintain stable expression of integrated constructs).

Lab Tek II Chambered Coverglass #1.5 Borosilicate (8 well).

Prepare or purchase commercially prepared tissue-culture grade poly-l-lysine (0.01%) and fibronectin (10 μg/mL) solutions.

1× PBS: 1.06 mM KH2PO4, 155.17 mM NaCl, 2.97 mM Na2HPO4-7H2O. Adjust pH to 7.4 and autoclave.

2.3. Preparing Reaction Mix for Nuclear Envelope Breakdown Assay

Make a master mix of energy regeneration reagents at a 1:1:2 (volume) ratio from the following stocks: ATP (0.2 M); creatine kinase (5 mg/mL); phosphocreatine (1 M).

2.4. Reagents for Permeabilization

Permeabilization buffer (PB): 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.3, 110 mM potassium acetate, 5 mM magnesium acetate, 0.5 mM EGTA, pH 8.0, 250 mM sucrose, 2 mM DTT. Prepare fresh each time, and store on ice.

Digitonin solution: from a stock solution of 10 mg/mL digitonin dissolved in DMSO (Calbiochem; see Note 1), make a fresh working solution of 40 μg/mL in 1× PB. Store on ice.

3. Methods

All steps are carried out at room temperature unless otherwise indicated.

3.1. Xenopus Egg Extract Preparation (17, 18)

Xenopus frogs are induced to lay eggs by a priming injection of 160 U human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG), followed ~7 days later with 500 U HCG. After the second injection, frogs lay eggs overnight into 100 mM NaCl. The eggs are collected the following morning in glass beakers.

After removing excess liquid, the eggs are dejellied in 2% cysteine solution for a total of 5 min (swirl and replace with fresh solution one to two times; 100 mL of 2% cysteine is used for 25 mL of eggs).

The cysteine is poured off and the eggs are washed three times with ¼ X MMR buffer and once with 1× MMR buffers.

The eggs are rinsed once with ELB (if preparing an interphase extract) or with Mitotic Buffer (if preparing a mitotic extract) and any eggs that are not clearly demarcated by light and dark hemispheres are removed with a plastic transfer pipette.

Rinse two times more with ELB/Mitotic buffer. In the last wash for interphase extract, use ELB supplemented with stocks of DTT (at 1:1,000) and cycloheximide (at 1:200 ratio).

The eggs are poured gently into a 15 mL round-bottom Falcon tube(s) and centrifuged in a clinical centrifuge set at 170 × g for 15 s, which compacts the eggs without breaking them. All excess buffer that collects on the top is then removed.

Aprotinin, leupeptin, and cytochalasin B are added to the top of the tube (at 1:1,000), which is then centrifuged in a Beckman JS 13.1 swinging bucket rotor at 15,680 × g for 15 min at 4°C. For interphase extracts, the rotor and centrifuge start at room temperature, whereas for mitotic extracts both are prechilled.

The yellowish/milky fraction, referred to as the S-fraction, immediately below a top layer of lipid is collected by puncturing the side of the falcon tube with an 18-gauge needle attached to a 10 mL syringe. The S-fraction is then transferred to a chilled 15 mL round-bottom falcon tube.

Aprotinin, leupeptin, and cytochalasin B are again added to the top surface and this tube is then centrifuged in Beckman JS13.1 rotor at 15,680 × g for 15 min at 4°C.

The lipid layer which collects on top is then carefully removed by suction and the remaining S-fraction is mixed well with glycerol to a final 5% volume.

The extract is aliquoted (~100 μL) and then flash frozen in liquid N2, followed by prolonged storage at −80°C. (see Note 2).

3.2. Plating Cells

Add 500 μL of poly-lysine solution per well to the chambered coverglass (see Notes 3 and 4) and leave inside the cell culture hood.

After 5 min, aspirate the poly-lysine and add 500 μL of fibronectin solution.

After 10 min, aspirate fibronectin and wash with sterile 1× PBS at least three times.

Plate HeLa cells stably expressing POM121-3GFP and Histone H2B-mCherry (see Note 5) at 4–8 × 104 cells per well and culture for 16–24 h, with ~40–50% confluency being optimal for imaging (see Note 6).

3.3. Preparing Soluble Components for Addition to HeLa Cells in Imaging Chamber

Thaw egg extract tubes at room temperature on bench top. For mitotic conditions, interphase and mitotic extracts are mixed at a ratio of 60:40.

For each reaction, add 6 μL energy regeneration mix per 200 μL extract.

Aliquot samples into respective 1.5 mL tubes, supplement with recombinant protein/inhibitors as desired (see Note 7), and incubate for 10–30 min.

3.4. Digitonin Permeabilization

Incubate imaging chamber slide with cells on ice for 5 min.

Aspirate medium, add 500 μL of ice-cold PB for 5 min.

Aspirate PB and add 400 μL of ice-cold digitonin solution, incubate for 5 min on ice (see Note 8).

Aspirate digitonin and wash gently with 400 μL of ice-cold PB three times.

After the last PB wash, add Xenopus extract mixture.

3.5. Setting Up and Analyzing Time-Lapse Microscopy

Place a drop of oil on the ×60 oil immersion lens of an inverted fluorescence microscope equipped with an automated stage. Mount the imaging chamber and position it in the middle of the slide holder (see Fig. 2). The refractive index of the oil used is 1.518.

In each well of interest, select 2–4 fields of 6–10 cells (see Note 9).

In addition to positions being set in the XY plane, set a series of Z positions to be acquired above and below the plane of focus (see Note 10).

Set up the software (an analytical package such as softWorx) so that images are acquired at 5-min intervals for 4–5 h (see Note 11).

After images are acquired, create a montage of relevant time points (for example, see Fig. 3).

To quantify nuclear envelope breakdown and determine whether particular treatments have altered its kinetics, score nuclei (see Note 12) for the presence of broken/discontinuous nuclear rim staining as visualized by POM121-3GFP (Fig. 3 and see Note 13) and graph totals over time (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Real-time imaging of nuclear envelope breakdown in permeabilized cells.HeLa cells stably expressing POM121-3GFP and Histone H2B-mCherry were permeabilized and incubated under mitotic (left panels) or interphase (right panels) conditions. Cells incubated with mitotic extract exhibited nuclear envelope breakdown and chromatin condensation characteristic of mitosis as time proceeded; arrows indicate when a particular nuclear envelope is first observed to lose continuity. The exact kinetics depends on the potency and quality of the batch of mitotic extract. In contrast, cells incubated with interphase extract maintain stable morphology over time, although the nuclei enlarge somewhat over time likely due to ongoing import. Scale bar, 20 μM.

Fig. 4.

Quantification of nuclear envelope breakdown in permeabilized cells The cumulative percentage of cells displaying broken/discontinuous POM121-3GFP-labeled nuclear envelope is plotted in a graph. Error bars indicate mean ± SD of four independent experiments in which >40 cells were counted in total.

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. Don Ayer, Einer Hallberg, Mary Dasso, and Maureen Powers for reagents and Drs. Mark Smith and Chris Rodesch and the University of Utah Fluorescence Microscopy Core Facility for assistance. Core facilities are supported in part by a grant (P30 CA042014) awarded to the Huntsman Cancer Institute. This work was funded by the National Institute of Health (grant R01 GM61275) and the Huntsman Cancer Foundation (to K.S.U.). D.R.M. is supported by an NIH Developmental Biology Training Grant (5T32 HD07491).

4. Notes

Digitonin stock should be aliquoted and stored at −20°C, avoiding repeated freeze-thaw cycles.

The interphase and mitotic Xenopus egg extracts can be quality tested by immunoblotting to detect whether the cell cycle stages are robustly preserved. We track Nup153 and look for a shift to a slower migrating form in mitotic conditions, as well as phospho-Histone H3, which should be readily detected only in the mitotic extract. The ratio of interphase to mitotic extract is empirically determined for the purpose of the assay. While egg extract provides a robust and plentiful source of cell cycle staged material that works optimally at room temperature, the assay is amenable to other sources such as mammalian cell lysates as well.

Coating chamber slides with a mixture of polylysine and fibronectin solution enhances cell attachment. Different cell types and imaging chamber surfaces may require different combinations of surfactants for optimal cell adherence.

With some microscope stages, only the middle four wells of the chambered coverglass can be used conveniently for imaging purposes.

The cell line used in Fig. 3 expresses POM121 tagged with three GFP moieties (19, 20) and Histone H2B-mCherry, for the reasons described in the Introduction. Other proteins, such as lamins, would also be interesting to tag and track using this method. One can also add soluble markers, such as fluorescently labeled proteins or dextrans of different sizes to track changes in nuclear permeability (9, 21).

Sufficient time in culture (at least 16–24 h) following plating onto the chambered coverglass slide is required for cells to spread and attach in order to prevent cell detachment during permeabilization. Cell numbers can be further optimized according to the requirements of the experiment.

To elucidate molecular pathways, this assay can be paired with small molecule enzymatic inhibitors or recombinant protein fragments that interfere with a particular protein function. In some cases, antibodies can also be used to block specific protein function. It may be necessary to pre-incubate the permeabilized cells with inhibitors as well.

Optimal digitonin concentrations are those that enable plasma membrane permeabilization while leaving the nuclear membrane intact. For every batch of digitonin and for different cell lines, both time and concentration should be tested and titrated to determine optimal conditions. We test the efficacy of the conditions by incubating permeabilized cells with interphase extract, energy mix, and rhodamine-labeled BSA-NLS-conjugated import substrate. This should result in robust nuclear levels of import cargo if the plasma membrane is permeable and the nuclear membrane has maintained its integrity.

Restricting the distance between XY points prevents the ×60 lens from “whipping around” and thinning the oil layer, which in the course of time can lead to focal drift.

Z sections can be useful if the plane of focus for a cell changes. Reducing the number of fields (XY positions) will enable more Z positions to be imaged in the same given time frame.

Values for intensity of light and time of exposure for each required filter set are adjusted keeping in mind that imaging works optimally with lower light intensity for longer exposure intervals, to reduce phototoxicity and photobleaching.

Zooming in on original images on screen and alternative Z sections (not just the selected images in the montage) may be necessary to evaluate morphological changes.

Different parameters can be tracked and, depending on the stage affected by the experimental conditions, this might be necessary in the evaluation. For instance, rather than tracking discontinuity in the nuclear rim, clearance of POM121 from the chromatin surface could be scored.

References

- 1.Guttinger S, Laurell E, Kutay U. Orchestrating nuclear envelope disassembly and reassembly during mitosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:178–191. doi: 10.1038/nrm2641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prunuske AJ, Ullman KS. The nuclear envelope: form and reformation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2006;18:108–116. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cotter L, Allen TD, Kiseleva E, Goldberg MW. Nuclear membrane disassembly and rupture. J Mol Biol. 2007;369:683–695. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Georgatos SD, Pyrpasopoulou A, Theodoropoulos PA. Nuclear envelope breakdown in mammalian cells involves stepwise lamina disassembly and microtubule-drive deformation of the nuclear membrane. J Cell Sci. 1997;110(pt 17):2129–2140. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.17.2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beaudouin J, Gerlich D, Daigle N, Eils R, Ellenberg J. Nuclear envelope breakdown proceeds by microtubule-induced tearing of the lamina. Cell. 2002;108:83–96. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00627-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salina D, Bodoor K, Eckley DM, Schroer TA, Rattner JB, Burke B. Cytoplasmic dynein as a facilitator of nuclear envelope breakdown. Cell. 2002;108:97–107. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00628-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muhlhausser P, Kutay U. An in vitro nuclear disassembly system reveals a role for the RanGTPase system and microtubule-dependent steps in nuclear envelope breakdown. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:595–610. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200703002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dultz E, Zanin E, Wurzenberger C, Braun M, Rabut G, Sironi L, Ellenberg J. Systematic kinetic analysis of mitotic dis- and reassembly of the nuclear pore in living cells. J Cell Biol. 2008;180:857–865. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200707026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lenart P, Rabut G, Daigle N, Hand AR, Terasaki M, Ellenberg J. Nuclear envelope breakdown in starfish oocytes proceeds by partial NPC disassembly followed by a rapidly spreading fenestration of nuclear membranes. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:1055–1068. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200211076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu J, Prunuske AJ, Fager AM, Ullman KS. The COPI complex functions in nuclear envelope breakdown and is recruited by the nucleoporin Nup153. Dev Cell. 2003;5:487–498. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00262-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murray AW, Kirschner MW. Cyclin synthesis drives the early embryonic cell cycle. Nature. 1989;339:275–280. doi: 10.1038/339275a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blow JJ, Laskey RA. A role for the nuclear envelope in controlling DNA replication within the cell cycle. Nature. 1988;332:546–548. doi: 10.1038/332546a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Newmeyer DD, Forbes DJ. Nuclear import can be separated into distinct steps in vitro: nuclear pore binding and translocation. Cell. 1988;52:641–653. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90402-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hetzer M, Meyer HH, Walther TC, Bilbao-Cortes D, Warren G, Mattaj IW. Distinct AAA-ATPase p97 complexes function in discrete steps of nuclear assembly. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:1086–1091. doi: 10.1038/ncb1201-1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Volkova EG, Kurchashova SY, Polyakov VY, Sheval EV. Self-organization of cellular structures induced by the overexpression of nuclear envelope proteins: a correlative light and electron microscopy study. J Electron Microsc (Tokyo) 2011;60:57–71. doi: 10.1093/jmicro/dfq067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Polychronidou M, Hellwig A, Grosshans J. Farnesylated nuclear proteins Kugelkern and lamin Dm0 affect nuclear morphology by directly interacting with the nuclear membrane. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:3409–3420. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-03-0230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higa MM, Ullman KS, Prunuske AJ. Studying nuclear disassembly in vitro using Xenopus egg extract. Methods. 2006;39:284–290. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kornbluth S, Yang J, Powers M, editors. Current protocols in cell biology. Wiley; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kihlmark M, Imreh G, Hallberg E. Sequential degradation of proteins from the nuclear envelope during apoptosis. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:3643–3653. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.20.3643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mackay DR, Makise M, Ullman KS. Defects in nuclear pore assembly lead to activation of an Aurora B-mediated abscission checkpoint. J Cell Biol. 2010;191:923–931. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201007124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lenart P, Ellenberg J. Monitoring the permeability of the nuclear envelope during the cell cycle. Methods. 2006;38:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]