Abstract

Peripheral nerve injury-induced changes in gene transcription and translation in primary sensory neurons of the dorsal root ganglion (DRG) are considered to contribute to neuropathic pain genesis. Transcription factors control gene expression. Peripheral nerve injury increases the expression of myeloid zinc finger protein 1 (MZF1), a transcription factor, and promotes its binding to the voltage-gated potassium 1.2 (Kv1.2) antisense RNA gene in the injured DRG. However, whether DRG MZF1 participates in neuropathic pain is still unknown. Here, we report that blocking the nerve injury-induced increase of DRG MZF1 through microinjection of MZF1 siRNA into the injured DRG attenuated the initiation and maintenance of mechanical, cold, and thermal pain hypersensitivities in rats with chronic constriction injury (CCI) of the sciatic nerve, without affecting locomotor functions and basal responses to acute mechanical, heat, and cold stimuli. Mimicking the nerve injury-induced increase of DRG MZF1 through microinjection of recombinant adeno-associated virus 5 expressing full-length MZF1 into the DRG produced significant mechanical, cold, and thermal pain hypersensitivities in naïve rats. Mechanistically, MZF1 participated in CCI-induced reductions in Kv1.2 mRNA and protein and total Kv current and the CCI-induced increase in neuronal excitability through MZF1-triggered Kv1.2 antisense RNA expression in the injured DRG neurons. MZF1 is likely an endogenous trigger of neuropathic pain and might serve as a potential target for preventing and treating this disorder.

Keywords: Myeloid zinc finger protein 1, Kv1.2 mRNA, Kv1.2 antisense RNA, Dorsal root ganglion, Neuropathic pain

1. Introduction

Neuropathic pain is a debilitating clinical condition due to its lancinating quality, unpredictable and spontaneous episodes, and resulting functional and emotional impairment [4;12;42]. It is caused by neurological disorders such as peripheral nerve and spinal cord injury, peripheral neuropathy, multiple sclerosis, and stroke [4]. Although medications currently used to treat neuropathic pain provide symptomatic relief, most of these medications are non-specific with regard to the cause of neuropathic pain [26;40]. Therefore, understanding pathological changes related to neuropathic pain may help shift the treatment strategy from symptomatic relief to neuropathic pain-specific therapies.

One of the common primary causes of peripheral neuropathic pain is hyperexcitability and abnormal ectopic firing that arises in neuromas at the sites of peripheral nerve injury and dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons[4;8]. Voltage-gated potassium (Kv) channels that are critical for establishing resting membrane potential and controlling the excitability of DRG neurons, are key players during neuropathic pain genesis [7;14;44]. In particular, Kv1.2, one of the alpha subunits in the Kv channel family, is highly expressed in most DRG neurons, although it is distributed in other body tissues [14;32;44]. Peripheral nerve injury down-regulates the expression of Kv1.2 mRNA and protein in the injured DRG through the nerve injury-induced promotion of DRG Kv1.2 antisense (AS) RNA expression [13;14;18;21;22;30;32;44]. Mimicking this downregulation by overexpression of DRG Kv1.2 AS RNA decreases total Kv current, depolarizes the resting membrane potential, reduces current threshold for activation of action potentials, increases the number of action potentials in the DRG neurons, and leads to neuropathic pain symptoms [44]. Rescuing this downregulation by blocking the nerve injury-induced increase in DRG Kv1.2 AS RNA impairs mechanical, cold, and heat pain hypersensitivities during the development and maintenance periods of neuropathic pain [14;25;44]. These lines of evidence indicate that Kv1.2 AS RNA is an endogenous instigator of neuropathic pain.

Myeloid zinc finger 1 (MZF-1), a transcription factor, contains 13 zinc finger domains that can bind DNA independently of each other [27]. The promoter region of the Kv1.2 AS RNA gene contains a consensus binding motif of MZF1. Peripheral nerve injury up-regulates the expression of MZF1 in the DRG and increases the binding activity of MZF1 to the promoter region of the Kv1.2 AS RNA gene [44]. MZF1 overexpression decreases the expression of Kv1.2 mRNA and protein through its activation of Kv1.2 AS RNA expression in DRG neurons [44]. Given that Kv1.2 AS RNA is a key player in neuropathic pain [14;25;44], it is very likely that DRG MZF1 contributes to the induction and maintenance of neuropathic pain.

In the present study, we first examined whether blocking the nerve injury-induced increase in DRG MZF1 expression affected neuropathic pain induced by chronic constriction injury (CCI) of the peripheral sciatic nerve. We then observed whether mimicking the nerve injury-induced increase in DRG MZF1 altered DRG Kv1.2 function, DRG neuronal excitability and nociceptive thresholds in naïve rats. Finally, we investigated whether these effects were attributed to changes in the expression of Kv1.2 AS RNA and Kv1.2 mRNA and protein in DRG.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal preparation

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (250–300 g) were housed on a standard 12-h light/dark cycle, with water and food pellets available ad libitum. To minimize intra- and inter-individual variability of behavioral outcome measures, animals were acclimated for 2–3 days before behavioral testing was performed. Animal experiments were conducted with the approval of the Animal Care and Use Committee at New Jersey Medical School and were consistent with the ethical guidelines of the National Institutes of Health and the International Association for the Study of Pain. All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering and to reduce the number of animals used. For behavioral testing, the experimenters were blind to surgical intervention and drug treatment condition. No any outliers were removed from the experiments.

2.2. Chronic constriction injury model

The CCI-induced neuropathic pain model was carried out as described previously [3]. Briefly, the rats were placed under anesthesia with isoflurane. The sciatic nerve was exposed and loosely ligated with 4-0 chromic gut thread at 4 sites with an interval of 1 mm. Sham animals received an identical surgery with the ligation excluded.

2.3. DRG microinjection

MZF1 siRNA (Catalog number: sc-45714) and its control scrambled siRNA (catalog number: sc-37007) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Dallas, TX). TurboFect in vivo transfection reagent (Thermo Scientific Inc., Pittsburgh PA) was used as a delivery vehicle for siRNA as described [19;36;43] to prevent degradation and enhance cell membrane penetration of siRNA. Recombinant adeno-associated virus 5 (rAAV5) plasmid constructs and virus production for full-length MZF1 were prepared as described [44]. The virus expressing enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) was used as a control. All viral particles were produced at the University of North Carolina Vector Core.

DRG microinjection was carried out as described [44]. In brief, a midline incision was made in the lower lumbar back region, and the L4/5 DRGs were exposed. Viral solution (2 μl, 4 × 1012) or siRNA mixed solution (2 μl, 10 μM) was injected into two sites in the L4 and L5 DRGs with a glass micropipette connected to a Hamilton syringe. The pipette was removed after 10 min. After injection, the surgical field was irrigated with sterile saline and the skin incision was closed with wound clips. The injected rats showed no signs of paresis or other abnormalities.

2.4. Behavioral testing

Paw withdrawal thresholds in response to mechanical stimuli were measured with the up–down testing paradigm as described previously [33]. Briefly, the unrestrained rat was placed in a plexiglas chamber on an elevated mesh screen. Von Frey hairs in log increments of force (0.41, 0.69, 1.20, 2.04, 3.63, 5.50, 8.51, 15.14 g) were applied to the plantar surface of the rat's left and right hind paws. The 2.041-g stimulus was applied first. If a positive response occurred, the next smaller von Frey hair was used; if a negative response was observed, the next larger von Frey hair was used. The test ended when (i) a negative response was obtained with the 15.14-g hair and (ii) three stimuli were applied after the first positive response. Paw withdrawal threshold was determined by converting the pattern of positive and negative responses to the von Frey filament stimulation to a 50% threshold value with formula provided by Dixon [6,11].

Paw withdrawal latencies to noxious cold (0°C) were measured with a cold plate, the temperature of which was monitored continuously [14;44]. A differential thermocouple thermometer (Harvard Apparatus, South Natick, MA) attached to the plate provided temperature precision of 0.1°C. Each rat was placed in a Plexiglas chamber on the cold plate, which was set at 0°C. The length of time between the placement of the hind paw on the plate and the animal jumping, with or without paw licking and flinching, was defined as the paw withdrawal latency. Each trial was repeated three times at 10-min intervals for each hindpaw. A cutoff time of 60 s was used to avoid tissue damage of both hindpaws.

Paw withdrawal latencies to noxious heat were measured with a Model 336 Analgesic Meter (IITC Inc./Life Science Instruments, Woodland Hills, CA, USA) [14;44]. Rats were placed in a Plexiglas chamber on a glass plate. A radiant heat was applied by aiming a beam of light through a hole in the light box through the glass plate to the middle of the plantar surface of each hind paw. When the animal lifted its foot, the light beam was turned off. The length of time between the start of the light beam and the foot lift was defined as the paw withdrawal latency. Each trial was repeated five times at 5-min intervals for each side. A cut-off time of 20 s was used to avoid tissue damage to the hind paw.

Locomotor function was examined according to the methods described previously [16;29;33]. The following tests were performed before and after DRG microinjection. (1) Placing reflex: The rat was held with the hind limbs slightly lower than the forelimbs, and the dorsal surfaces of the hind paws were brought into contact with the edge of a table. The experimenter recorded whether the hind paws were placed on the table surface reflexively; (2) Grasping reflex: The rat was placed on a wire grid and the experimenter recorded whether the hind paws grasped the wire on contact; (3) Righting reflex: The rat was placed on its back on a flat surface and the experimenter noted whether it immediately assumed the normal upright position. Scores for placing, grasping, and righting reflexes were based on counts of each normal reflex exhibited in five trials. In addition, the rats’ general behaviors, including spontaneous pain-associated activity, were observed.

2.5. RNA extraction and quantitative real time RT-PCR

After behavioral tests, bilateral L4/5 DRGs were collected. Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). RNA was treated with a DNA-free Kit (Ambion, Austin, TX), and reverse-transcribed using the ThermoScript reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions with either the oligo (dT) primers or specific reverse primers. cDNA was amplified by real-time PCR using the primers listed in Table 1 (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA). GAPDH was used as an internal control for normalization. Each sample was run in triplicate in a 20 μL reaction with 250 nM forward and reverse primers, 10 μL of SsoAdvanced Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) and 20 ng of cDNA. Reactions were performed in a BIO-RAD CFX96 real-time PCR system. The cycle parameters were set as follows: an initial 3 min incubation at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s. Ratios of ipsilateral-side mRNA levels to contralateral-side mRNA levels were calculated by using the ΔCt method (2-ΔΔCt). All data were normalized to GAPDH, which has been demonstrated to be stable even after peripheral nerve injury insult [44].

Table 1.

Primers used for RT-PCR

| Primer names | Sequences |

|---|---|

| GAPDH-RT | TCC TGT TGT TAT GGG GTC TG |

| Kv1.2-RT | GGG TGA CTC TCA TCT TTG GA |

| Kv1.2AS-RT | CTG GCA GCA TCA TAA TAA TAG |

| GAPDH-F | TCG GTG TGA ACG GAT TTG GC |

| GAPDH-R | CCT TCA GGT GAG CCC CAG C |

| Kv1.2-F | CCC ATC TGC AAG GGC AAC GT |

| Kv1.2-R | CAC AGC CTC CTT TGG CTG GC |

| Kv1.2 AS-F | CTG AGG ACA GCC AGG AGG A |

| Kv1.2 AS-R | GCT TGA GGG ACA GTG AGA TG |

| MZF1-F | AAG TAG AAG GCA TCT TGT CGC |

| MZF1-R | CCT GGA TCG CTG GGG AGT |

RT: Reverse-transcription. F: Forward. R: Reverse.

2.6. Western blot analysis

Bilateral L4/5 DRGs were collected after behavioral tests and homogenized with ice-cold lysis buffer (10 mM Tris, 5 mM EGTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, 2 mM benzamidine, 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 40 μM leupeptin, 150 mM NaCl, 1% phosphatase inhibitor cocktail I and cocktail II). The crude homogenate was centrifuged at 4 °C for 15 minutes at 1,000 g. For Kv1.2 and β-actin, the supernatant (membrane and cytosolic fractions) was collected. For MZF1 and H3, the pellet (nuclear fraction) was collected and dissolved in lysis buffer containing 2% SDS and 0.1% Triton X-100. After protein concentration was measured, the samples were heated at 99°C for 5 minutes and loaded onto a 4% stacking/7.5% separating SDS-polyacrylamide gel (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The proteins were then electrophoretically transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Immobilon-P, Millipore). The membranes were blocked with 3% nonfat milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween-20 for 1 hour and then incubated with primary antibodies overnight under gentle agitation. These antibodies included rabbit anti-MZF1 (1:200, gift from Dr. D.Y.H. Tuan, Georgia Regents University), rabbit anti-H3 (1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology), mouse anti-Kv1.2 (1:200, NeuroMab), and mouse anti–β-actin (1:3,000, Sigma-Adrich). H3 and β-actin were used as internal loading controls for MZF1 and Kv1.2, respectively. The proteins were detected by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit secondary antibody and visualized by chemiluminescence regents (ECL; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ). The image signals were captured by a ChemiDoc imaging system and analyzed using Quantity One program (Biorad, Hercules, CA). The blot density from the control group was set as 100%. The relative density values from the other groups were determined by dividing the optical density values from these groups by the control value after each was normalized to the corresponding H3 or β-actin.

2.7. Whole-cell patch clamp recording

Whole-cell patch clamp recording was carried out as described [44] 5 weeks after viral injection into the DRG. Briefly, fresh dissociated rat DRG neurons were first prepared. The recording was carried out 4 to 10 h after plating. Coverslips were placed in the perfusion chamber (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT). Only green-labeled neurons were recorded. The electrode resistances of micropipettes ranged from 2 to 4 MΩ. Cells were voltage-clamped with an Axopatch-700B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). The intracellular pipette solution contained (in mM) potassium gluconate 120, KCl 20, MgCl2 2, EGTA 10, HEPES 10, Mg-ATP 4 (pH 7.3 with KOH, 310 mOsm). To minimize the Na+ and Ca2+ component in voltage-gated potassium current, an extracellular solution was composed of (in mM) choline chloride 150, KCl 5, CdCl2 1, CaCl2 2, MgCl2 1, HEPES 10, glucose 10 (pH 7.4 with Tris base, 320 mOsm). Signals were filtered at 1 kHz and digitized by using a DigiData 1550 with pClamp 10.4 software (Molecular Devices). Series resistance was compensated by 60–80%. Cell membrane capacitances were acquired by reading the value for whole-cell capacitance compensation directly from the amplifier. An online P/4 leak subtraction was performed to eliminate leak current contribution. The data were stored on computer by a DigiData 1550 interface and were analyzed by the pCLAMP 10.4 software package (Molecular Devices).

To record the action potential (AP), we switched the recording mode into current clamp. Coverslips were placed in the chamber and perfused with extracellular solution consisting of (in mM) NaCl 140, KCl 4, CaCl2 2, MgCl2 2, HEPES 10 and glucose 5, with pH adjusted to 7.38 by NaOH. The intracellular pipette solution contained (in mM) KCl 135, Mg-ATP 3, Na2ATP 0.5, CaCl2 1.1, EGTA 2 and glucose 5; pH was adjusted to 7.38 with KOH and osmolarity adjusted to 300 mOsm with sucrose. The resting membrane potential was taken 3 min after a stable recording was first obtained. To determine the incidence of spontaneous activity, individual green cells first were impaled with a recording electrode. If spontaneous activity was absent during the first 1 min of the impaling, AP was evoked by injecting current pulses (100–1400 pA, 200 ms) into the soma through the recording electrode. The injection current threshold was defined as the minimum current required to evoke the first AP. The membrane potential was held at the existing resting membrane potential during the current injection. The AP threshold was defined as the first point on the rapid rising phase of the spike at which the change in voltage exceeded 50 mV/ms. The AP amplitude was measured between the peak and the baseline. The membrane input resistance for each cell was obtained from the slope of a steady-state I–V plot in response to a series of hyperpolarizing currents, 200-ms duration delivered in steps of 100 pA from 200 pA to −2,000 pA. The after-hyperpolarization amplitude was measured between the maximum hyperpolarization and the final plateau voltage, and the AP overshoot was measured between the AP peak and 0 mV. The data were stored on a computer by a DigiData 1500 interface and were analyzed by the pCLAMP 10.4 software package (Molecular Devices). All experiments were performed at room temperature.

2.8. Statistical analysis

All results are collected randomly and given as means ± SEM. After the data distribution was tested to be normal, the data were statistically analyzed with two-tailed, paired/unpaired Student's t test and a one-way or two-way ANOVA. When ANOVA showed a significant difference, pairwise comparisons between means were tested by the post hoc Tukey method or Fisher's protected LSD post-hoc test (SigmaStat, San Jose, CA). Significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Effect of DRG MZF1 knockdown on neuropathic pain in CCI rats

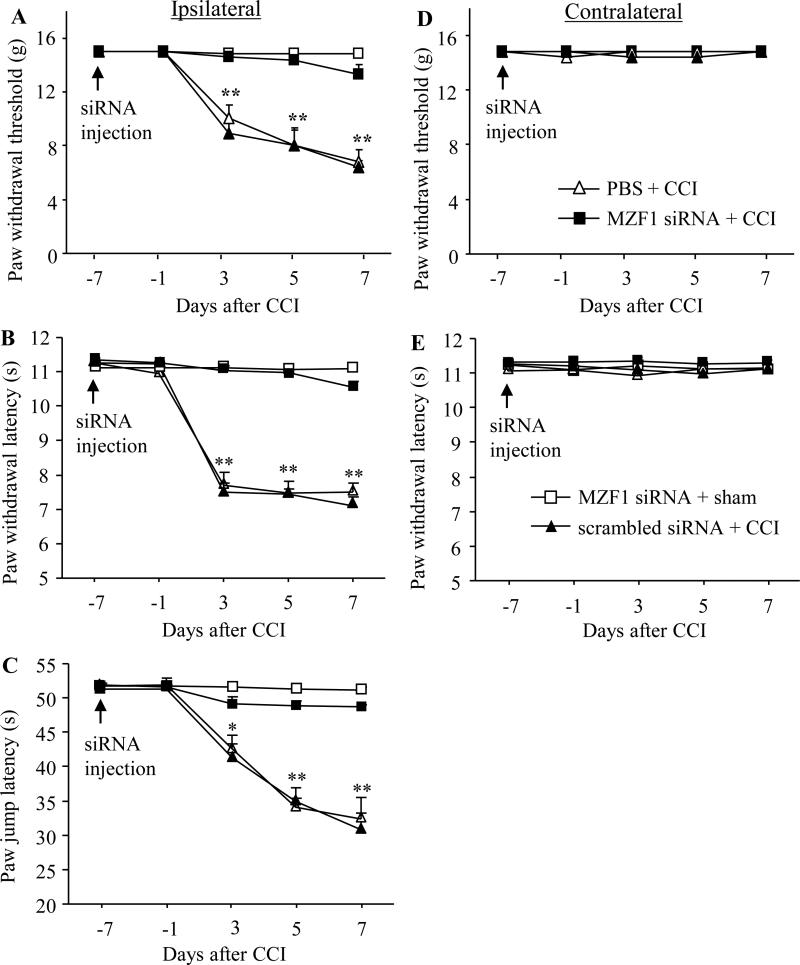

Peripheral nerve injury increased MZF1 expression in injured DRG [44]. To examine whether this increase was involved in neuropathic pain, we used a siRNA strategy to observe whether blocking the increase through microinjection of MZF1 siRNA into ipsilateral L4/5 DRGs affected CCI-induced neuropathic pain. Scrambled siRNA was used as a control. Selectivity and specificity of MZF1 siRNA have been characterized as described [44]. According to the previous reports [19;36;43], significant targeted protein knockdown via the TurboFect-mediated delivery of siRNA was observed on day 7 post-injection and persisted for at least 2 weeks. To examine the role of DRG MZF1 in the development of CCI-induced neuropathic pain, we carried out the CCI model on day 7 post-injection. Consistent with previous studies [3;38], CCI led to long-term mechanical, thermal, and cold pain hypersensitivities on the ipsilateral side in the vehicle-injected rats (n = 8 rats). The paw withdrawal thresholds in response to mechanical stimuli applied to the ipsilateral hind paw were significantly reduced as compared to pre-injury baseline values, a behavioral indication of mechanical pain hypersensitivity (Fig. 1A). Similarly, the paw withdrawal latency and jump latency of the ipsilateral hind paw in response to heat and cold, respectively, were dramatically less than those at baseline, an indication of thermal and cold pain hypersensitivities, respectively (Fig. 1B and C). Pain hypersensitivity appeared at day 3, reached a peak on days 5-7, and lasted for at least 17 days post-surgery (Figs. 1 and 2). Pre-injection of MZF1 siRNA did not alter basal paw responses to mechanical, heat, or cold stimuli on the ipsilateral hind paws of sham rats (n = 8 rats; Fig. 1A, B, and C), but pre-injection of MZF1 siRNA abolished CCI-induced pain hypersensitivities (n = 8 rats; Fig. 1). Compared to the baseline level, there were no significant decreases in paw withdrawal threshold in response to mechanical stimuli and paw latency to heat or cold stimuli on the ipsilateral side of the MZF1 siRNA-treated rats (Fig. 1A, B, and C). As expected, pre-injection of scrambled siRNA did not affect the CCI-induced pain hypersensitivities on the ipsilateral side during the observation period and there was no marked difference in paw withdrawal threshold or latency between the scrambled siRNA-injected (n = 8 rats) and vehicle-injected groups (Fig. 1A, B, and C). Pre-treatment of neither MZF1 siRNA nor scrambled siRNA changed basal paw threshold or latency on the contralateral side (Fig. 1D and E).

Fig. 1.

Effect of pre-injection of MZF1 siRNA into the injured DRG on CCI-induced pain hypersensitivity during the development period. Pre-injection of MZF1 siRNA, but not scrambled siRNA, into the ipsilateral L4/5 DRGs abolished CCI-induced decreases in paw withdrawal threshold in response to mechanical stimuli (A), in paw withdrawal latency in responses to heat stimulation (B), and in paw jump latency in response to cold stimulation (C) on the ipsilateral side on days 3, 5, and 7 post-CCI. Neither MZF1 siRNA nor scrambled siRNA altered basal paw responses to mechanical (D) and heat (E) stimuli on the contralateral side of CCI rats during the observation period. No changes in basal paw responses were observed on either ipsilateral or contralateral side in sham rats injected with MZF1 siRNA (A-E). n = 8 rats/group. *P < 0.05 or **P < 0.01 vs the corresponding baseline.

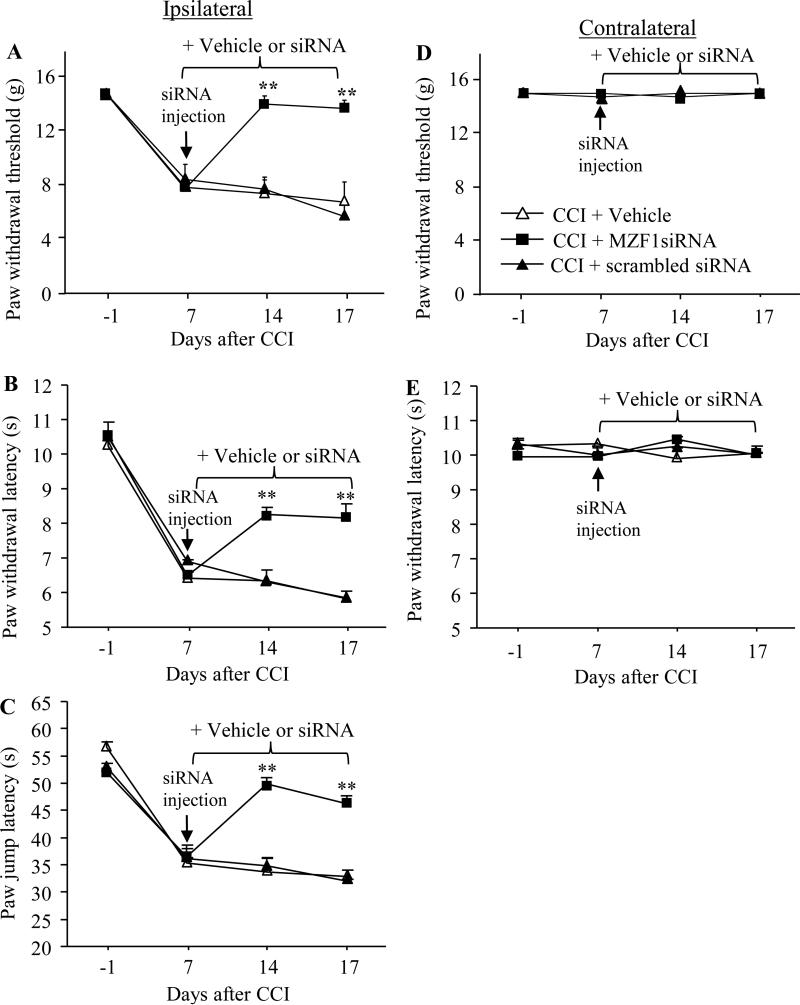

Fig. 2.

Effect of post-injection of MZF1 siRNA into the injured DRG on CCI-induced pain hypersensitivity during the maintenance period. Microinjection of MZF1 siRNA, but not scrambled siRNA, into the ipsilateral L4/5 DRGs on day 7 post-CCI significantly reversed CCI-induced decreases in paw withdrawal threshold in response to mechanical stimuli (A), in paw withdrawal latency in responses to heat stimulation (B), and in paw jump latency in response to cold stimulation (C) on the ipsilateral side on days 14 and 17 post-CCI. Neither MZF1 siRNA nor scrambled siRNA altered basal paw responses to mechanical (D) and heat (E) stimuli on the contralateral side of CCI rats during the observation period. n = 5 rats/group. **P < 0.01 vs the CCI plus vehicle group at the corresponding time points.

To further examine the role of DRG MZF1 in the maintenance of CCI-induced neuropathic pain, we microinjected vehicle or siRNA on 7 day post-CCI and carried out the behavioral test 14 and 17 days post-CCI. Post-injection of MZF1 siRNA (n = 5 rats), but not scrambled siRNA (n = 5 rats), significantly reduced CCI-induced pain hypersensitivities on the ipsilateral side during the maintenance period (Fig. 2A, B, and C). On 14 and 17 days post-CCI, paw withdrawal threshold in response to mechanical stimuli increased by 3.0-fold and 2.9-fold, respectively (Fig. 2A), paw withdrawal latency in response to heat stimuli increased by 1.3-fold and 1.4-fold, respectively (Fig. 2B), and paw jump latency in response to cold stimuli increased by 1.5-fold and 1.4-fold, respectively (Fig. 2C), compared with the corresponding vehicle-injected group (n = 5 rats). As expected, post-injection of vehicle, MZF1 siRNA, or scrambled siRNA did not alter basal paw responses to mechanical, heat, and cold stimuli applied to the contralateral hind paw during the maintenance period (Fig. 2D and E).

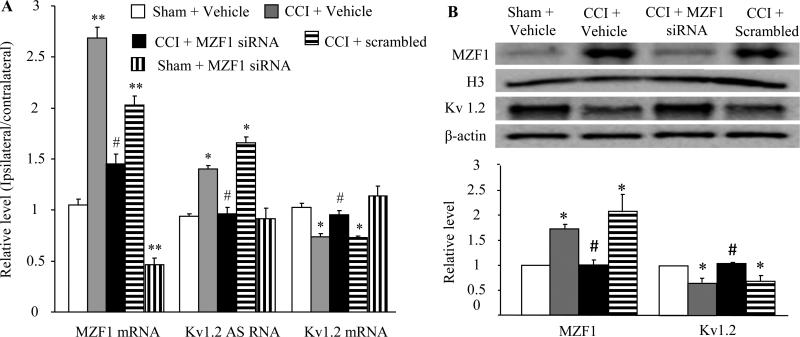

3.2. Effect of DRG MZF1 knockdown on the expression of Kv1.2 AS RNA and Kv1.2 mRNA and protein in DRG after CCI

In in vitro cultured HEK-293T cells or in in vitro cultured DRG neurons, MZF1 regulated the expression of Kv1.2 mRNA and protein through its activation of the Kv1.2 AS RNA gene [44]. We further examined whether microinjection of MZF1 siRNA into the ipsilateral L4/5 DRGs affected the expression of Kv1.2 AS RNA and Kv1.2 mRNA and protein in the injured DRG of CCI rats in vivo. As expected, CCI significantly increased the expression of MZF1 mRNA and protein and Kv1.2 AS RNA and reduced the expression of Kv1.2 mRNA and protein in the ipsilateral (but not contralateral) L4/5 DRGs on day 7 (Fig. 3) and day 14 (data not shown) post-CCI. The levels of MZF1 mRNA and protein in the CCI plus vehicle-treated group increased by 2.6-fold (Fig. 3A) and 1.7-fold (Fig. 3B), respectively, compared with the corresponding sham plus vehicle-treated group. The amount of Kv1.2 AS RNA in the CCI plus vehicle-treated group increased by 1.5-fold of the value in the sham plus vehicle-treated group (Fig. 3A). In contrast, the levels of Kv1.2 mRNA and protein decreased by 28% (Fig. 3A) and 35% (Fig. 3B), respectively, compared with the corresponding sham plus vehicle-treated group. MZF1 siRNA significantly blocked CCI-induced increases in MZF1 mRNA and protein and Kv1.2 AS RNA and rescued CCI-induced reductions in Kv1.2 mRNA and protein in the ipsilateral L4/5 DRGs on day 7 (Fig. 3) and day 14 (data not shown) post-CCI. The level of MZF1 mRNA in the MZF1 siRNA plus CCI-treated group decreased by 46% of the value in the CCI plus vehicle-treated group (Fig. 3A). The amounts of MZF1 protein, Kv1.2 AS RNA, and Kv1.2 mRNA and protein in the MZF1 siRNA plus CCI-treated group almost returned to the level in the sham plus vehicle-treated group (Fig. 3). As a control, MZF1 scrambled siRNA did not markedly affect CCI-induced increases in MZF1 mRNA and protein and Kv1.2 AS RNA and CCI-induced decreases in Kv1.2 mRNA and protein (Fig. 3). MZF1 siRNA also reduced the basal expression of MZF1 mRNA in the sham plus MZF1 siRNA-treated group (Fig. 3A). However, there were no significant differences in the levels of Kv1.2 AS RNA and Kv1. 2 mRNA between the sham plus MZF1 siRNA-treated and sham plus vehicle-treated groups (Fig. 3A). It is likely that a low basal level of Kv1.2 AS RNA cannot be further decreased even if the basal level of MZF1 is decreased in the DRG under normal conditions.

Fig. 3.

Effect of microinjection of MZF1 siRNA into the injured DRG on the expression of MZF1 mRNA and protein, Kv1.2 AS RNA, and Kv1.2 mRNA and protein in the injured DRG on day 7 post-CCI or sham surgery. (A) CCI increased the expression of MZF1 mRNA and Kv1.2 AS RNA and decreased the expression of Kv1.2 mRNA in the ipsilateral L4/5 DRGs. These effects were significantly blocked by pre-injection of MZF1 siRNA, but not scrambled siRNA. The level of MZF1 mRNA was reduced in the sham rats pre-injected with MZF1 siRNA. (B) CCI increased the expression of MZF1 protein and decreased the expression of Kv1.2 protein the ipsilateral L4/5 DRGs. These effects were markedly blocked by pre-injection of MZF1 siRNA, but not scrambled siRNA. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs the corresponding sham plus vehicle group. n = 3 rats/assay. #P < 0.05 vs the corresponding CCI plus vehicle group.

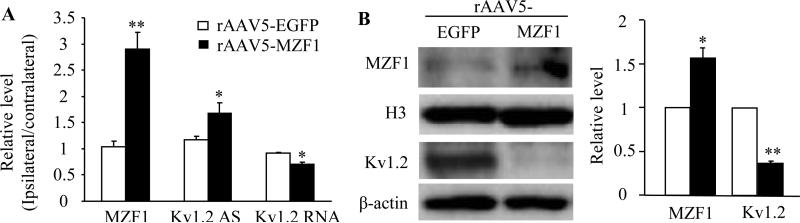

3.3. Effect of DRG MZF1 overexpression on Kv1.2 AS RNA and Kv1.2 mRNA and protein in naïve rats

We next examined whether mimicking the CCI-induced increase in DRG MZF1 through microinjection of rAAV5-MZF1 into unilateral L4/5 DRGs altered the expression of Kv1.2 AS RNA and Kv1.2 mRNA and protein in the DRGs of naïve rats in vivo. As expected, the levels of MZF1 mRNA and protein in the injected DRGs of the rAAV5-MZF1-injected group significantly increased by 2.9-fold and 1.6-fold, respectively, of the values in the injected DRGs of the rAAV5-EGFP-injected group, (Fig. 4A and B). Injection of rAAV5-MZF1 into unilateral L4/5 DRGs activated the expression of Kv1.2 AS RNA and down-regulated the expression of Kv1.2 mRNA and protein in the injected DRGs (Fig. 4A and B). The amount of Kv1.2 AS RNA in the injected DRGs of the rAAV5-MZF1-injected group increased by 1.4-fold compared to the rAAV5-EGFP-injected group. The levels of Kv1.2 mRNA and protein decreased by 20% and 64%, respectively, of the value in the rAAV5-EGFP-injected group.

Fig. 4.

Effect of microinjection of rAAV5-MZF1 into the DRG on the expression of MZF1 mRNA and protein, Kv1.2 AS RNA, and Kv1.2 mRNA and protein in the DRG of naïve rats. (A) Injection of rAAV5-MZF1 into unilateral L4/5 DRGs produced increases in the levels of MZF1 mRNA and Kv1.2 AS RNA and a decrease in the amount of Kv1.2 mRNA in the ipsilateral L4/5 DRGs. (B) Injection of rAAV5-MZF1 into unilateral L4/5 DRGs produced an increase in the level of MZF1 protein and a decrease in the amount of Kv1.2 protein in the ipsilateral L4/5 DRGs. N = 3 rats/assay. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs the corresponding AAV5-EGFP group.

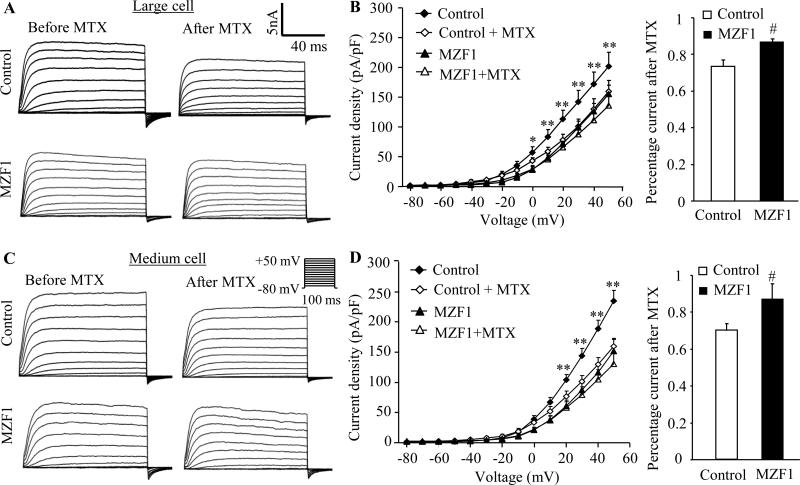

3.4. Effect of DRG MZF1 overexpression on total Kv current and excitability in DRG neurons of naïve rats

Using patch clamp recording, we further observed the changes of total Kv current and excitability in DRG neurons 5-6 weeks after rAAV5-MZF1 injection. To increase the recording efficiency, we injected rAAV5-EGFP alone (control group) or a mixed viral solution of rAAV5-MZF1 plus rAAV5-EGFP (MZF1-injected group). Given that contribution of small (< 25 μm) DRG neurons to neuropathic pain is still a puzzle [1;2;20;28;31;34] and that rAAV was transduced predominantly in large (>35 μm) and medium (25~35 μm) DRG neurons [44], only large and medium green DRG neurons were recorded. The voltage-clamp recording showed that total Kv current density in the MZF1-injected group was significantly reduced in large and medium DRG neurons compared to the control group (Fig. 5). Bath application of 100 nM maurotoxin (MTX), a selective Kv1.2 current inhibitor [5;15;39], was used to identify whether this reduction was due to the MZF1-induced DRG Kv1.2 decrease. MTX produced a significant reduction in total Kv current in large (n = 11 neurons in control group from 8 DRGs of 4 rats; n = 14 neurons in the MZF1-treated group from 8 DRGs of 4 rats) and medium (n = 17 neurons in control group from 8 DRGs of 4 rats; n = 16 neurons in the MZF1-treated group from 8 DRGs of 4 rats) neurons from the control group, but not from the MZF1–treated group, at depolarizing voltages (Fig. 5A-D). When tested at +50 mV, large and medium neurons in the control group retained 74% and 70% of current after MTX treatment, however, large and medium neurons from the MZF1-treated group retained 88% and 87% of current (Fig. 5B and D).

Fig. 5.

Effect of microinjection of rAAV5-MZF1 into the DRG on total Kv current in large and medium DRG neurons. (A) Representative traces of total Kv current in large DRG neurons from control (rAAV5-EGFP)- and MZF1(rAAV5-MZF1 plus rAAV5-EGFP)-treated rats before or after bath perfusion of 100 nM maurotoxin (MTX). (B) Left: I-V curve for control- and MZF1-treated large DRG neurons before or after 100 nM MTX treatment. The current density was plotted against each step testing voltage. Right: at +50 mV, the reduction in total Kv current after MTX treatment in large DRG neurons was greater in the control group than in the MZF1-treated group. n = 11 cells for control group (8 DRGs from 4 rats) and n = 14 for MZF1-treated group (8 DRGs from 4 rats). (C) Representative traces of total Kv current in medium DRG neurons from control- and MZF1-treated rats before or after bath perfusion of 100 nM MTX. (D) Left: I-V curve for control- and MZF1-treated medium DRG neurons before or after 100 nM MTX treatment. The current density was plotted against each step testing voltage. Right: at +50 mV, the reduction in total Kv current after MTX treatment in medium DRG neurons was greater in the control group (8 DRGs from 4 rats) than in the MZF1-treated group (8 DRGs from 4 rats). n = 17 cells for control group and n = 16 for MZF1-treated group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.1 vs the corresponding the MZF1-treated group. #P < 0.05 vs the corresponding control group.

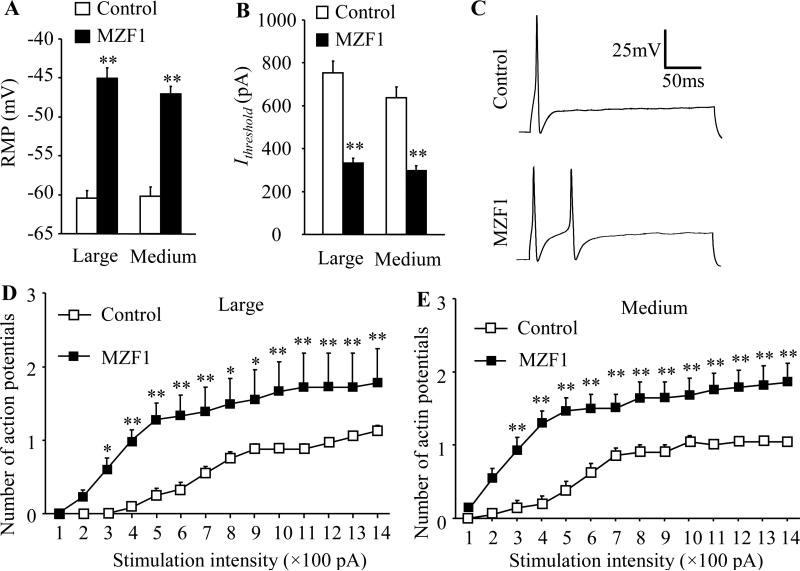

Whole-cell current-clamp recording was further used to assess DRG neuronal excitability. Spontaneous firing was seen in 6% (1/18) of large neurons and 14% (4/28) of medium neurons from the MZF1-injected group. No spontaneous firing was detected in both large and medium neurons from the control group. The resting membrane potentials in the MZF1-injected group were significantly increased by 15.4 mV and 13.2 mV, respectively, in large and medium neurons compared to the control group (Fig. 6A). The current thresholds in the MZF1-injected group were decreased by 56% and 54% of the values in the control group in large and medium neurons, respectively (Fig. 6B). The average number of APs evoked by stimulation of ≥300 pA in the MZF1–injected group was greater than that in the control group in large and medium neurons (Fig. 6C-E). Additionally, compared to the control group, MZF1 injection significantly reduced AP amplitude by 19% and 24% in large and medium neurons, respectively, and AP overshoot by 41% in medium neurons (Table 2). There were no significant differences between the two groups in membrane input resistances or other AP parameters, such as AP threshold, duration and after-hyperpolarization amplitude (Table 2).

Fig. 6.

Effect of microinjection of rAAV5-MZF1 into the DRG on excitability in large and medium DRG neurons. n = 24 large, 21 medium for control group (8 DRGs from 4 rats) and n = 18 large, 28 medium for MZF1-treated group (8 DRGs from 4 rats). (A, B) Resting membrane potential (RMP; A) and current threshold for pulses (Ithreshold; B). **P < 0.01 vs the corresponding control group. (C) Representative traces of the evoked action potentials in large DRG neurons. (D, E) Numbers of evoked action potentials from large (D) and medium (E) DRG neurons of control and MZF1-treated rats after application of different currents. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs the corresponding same stimulation intensity in the control group.

Table 2.

Effect of MZF1 on membrane input resistance and other action potential parameters in the DRG

| n | Large cell | Medium cell | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | MZF1 | t/p value | Control | MZF1 | t/p value | |

| 24 cells, 4 rats | 18 cells, 4 rats | 21 cells, 4 rats | 28 cells, 4 rats | |||

| Rin, mQ | 45.03±2.67 | 43.86±3.61 | 0.27/0.79 | 43.30±3.53 | 42.07±2.53 | 0.29/0.77 |

| APT, mV | −15.18±1.31 | −13.36±0.94 | −1.06/0.30 | −14.88±1.00 | −14.46±1.07 | −0.28/0.78 |

| APO, mV | 46.56±4.20 | 36.33±3.69 | 1.76/0.09 | 44.51±2.83 | 26.32±1.95 | 5.46/<0.001 |

| APA, mV | 100.60±3.19 | 81.69±4.14 | 3.68/<0.001 | 98.67±3.93 | 75.44±2.12 | 5.54/<0.001 |

| AHPA, mV | −19.97±1.02 | −19.04±1.62 | −0.51/0.62 | −19.42±1.23 | −17.31±1.55 | −1.02/0.313 |

Values are mean ± SEM. Rin: membrane input resistance. APA: action potential amplitude. APT: action potential threshold. APO: action potential overshoot. AHPA: afterhyperpolarization amplitude.

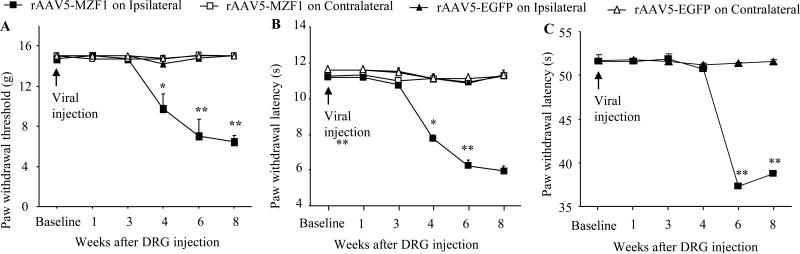

3.5. Effect of DRG MZF1 overexpression on nociceptive thresholds in naïve rats

We also examined whether microinjection of rAAV5-MZF1 into unilateral L4/5 DRGs produced changes in nociceptive thresholds. Injection of rAAV5-MZF1 (n = 5 rats), but not of control rAAV5-EGFP (n = 6 rats), led to mechanical, thermal, and cold pain hypersensitivities as demonstrated by ipsilateral decreases in paw withdrawal threshold in response to mechanical stimuli (Fig. 7A), paw withdrawal latencies in response to heat (Fig. 7B), and paw jump latencies in response to cold (Fig. 7C). These hypersensitivities developed between 4 to 6 weeks and persisted for at least 8 weeks (Fig. 7), which is consistent with the fact that rAAV5 takes 3-4 weeks to become expressed in in vivo and that this expression lasts for at least 3 months [14;44]. Neither rAAV5-MZF1 nor rAAV-EGFP altered basal paw responses to mechanical, heat, and cold stimuli on the contralateral side (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Effect of microinjection of rAAV5-MZF1 into the DRG on nociceptive threshold in naïve rats. Paw withdrawal responses to mechanical (A), heat (B), and cold (C) stimuli from the rAAV5-EGFP-injected (n = 6 rats) and rAAV5-MZF1-injected (n = 5 rats) groups. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs the rAAV5-EGFP-injected group on the ipsilateral side at the corresponding time points.

3.6. Effect of DRG MZF1 knockdown or overexpression on locomotor function

To exclude the possibility that the effect of DRG MZF1 knockdown or overexpression on behavioral responses described above was caused by impaired locomotor functions (or reflexes), we finally examined locomotor functions of experimental rats after pain behavioral tests as described above. As shown in Table 3, the rats injected with either vehicle, MZF1 siRNA, scrambled siRNA, rAAV5-MZF1, or rAAV5-EGFP displayed normal locomotor functions, including placing, grasping, and righting reflexes. Convulsions and hypermobility were not observed in any of the injected rats.

Table 3.

Mean (SEM) changes in locomotor function

| Group | Functional test Placing | Grasping | Righting |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle + CCI | 5 (0) | 5 (0) | 5 (0) |

| MZF1 siRNA + CCI | 5 (0) | 5 (0) | 5 (0) |

| MZF1 siRNA + sham | 5 (0) | 5 (0) | 5 (0) |

| Scrambled siRNA + CCI | 5 (0) | 5 (0) | 5 (0) |

| rAAV5-EGFP | 5 (0) | 5 (0) | 5 (0) |

| rAAV5-MZF1 | 5 (0) | 5 (0) | 5 (0) |

n = 5 rats/group. 5 trials. CCI: chronic constriction injury. EGFP: enhanced green fluorescent protein. MZF1: myeloid zinc finger protein 1. rAAV5: recombinant adeno-associated virus 5.

4. Discussion

CCI-induced peripheral nerve injury produces long-term pain hypersensitivity in a rat model that mimics trauma-induced neuropathic pain observed in the clinic. Exploring the mechanisms that underlie pain hypersensitivity may lead to novel therapeutic strategies for its prevention and treatment. Abnormal ectopic firing that arises from neuromas at the sites of peripheral nerve injury and DRG neurons is critical for neuropathic pain genesis [23;35], but how this firing develops following peripheral nerve injury is still elusive. Here, we report that DRG MZF1 may participate in a CCI-induced increase in DRG neuronal excitability and pain hypersensitivity. MZF1 may be a new target for the prevention and treatment of peripheral neuropathic pain.

The present study showed that DRG MZF1 knockdown caused by microinjection of MZF1 siRNA into the injured DRG significantly reduced mechanical, thermal, and cold pain hypersensitivities during both the development and maintenance of CCI-induced neuropathic pain. This anti-hyperalgesic effect may be related to the functional role of MZF1 in nerve injury-induced down-regulation of Kv1.2 mRNA and protein triggered by Kv1.2 AS RNA in the injured DRG. The promoter region of the Kv1.2 AS RNA gene, but not the Kv1.2 sense RNA gene, contains the consensus binding motif of MZF1 [44]. Once bound to this motif, MZF1 promotes transcription of target genes, including the Kv1.2 AS RNA gene in in vitro cultured cell lines or cultured DRG neurons [17;24;44]. It has been demonstrated previously that peripheral nerve injury alters the expression in the levels of thousands of RNA transcripts, including an increase in Kv1.2 AS RNA, in the neurons of the injured DRG [4;8;14;44]. Kv1.2 AS RNA up-regulation may be responsible for spinal nerve ligation (SNL) or CCI-induced down-regulation of Kv1.2 mRNA and protein in the injured DRG, resulting in a reduction in total Kv current and an increase in excitability in the injured large and medium DRG neurons [14;44]. The latter is associated with initiation and maintenance of pain hypersensitivity on the injured side following SNL or CCI [23;35]. The results in the present study further demonstrate that MZF1 is required for the CCI-induced increase in Kv1.2 AS RNA and the reduction in Kv1.2 mRNA and protein in the injured DRG, as these effects were abolished by DRG MZF1 knockdown. In addition, DRG MZF1 overexpression increased Kv1.2 AS RNA and reduced Kv1.2 mRNA and protein in the injected DRG. Given that MZF1 mRNA is co-localized with Kv1.2 AS RNA and Kv1.2 mRNA in the large and medium DRG neurons and that SNL or CCI increased the expression of MZF1 and its binding to the Kv1.2 AS RNA gene in the injured DRG [44], it is very likely that the anti-hyperalgesic effect caused by blocking the nerve injury-induced increase in DRG MZF1 might result from the failure of Kv1.2 AS RNA expression to increase following nerve injury. Without the increase in Kv1.2 AS RNA expression, no changes would occur in Kv1.2 mRNA and protein levels and subsequent total Kv current and neuronal excitability in the DRG neurons. It should be noted that peripheral nerve injury also produces long-lasting ongoing pain. Whether DRG MZF1 is required for nerve injury-induced ongoing pain is unknown and remains to be examined in the future. Taken together, our findings suggest that DRG MZF1 is a key player in neuropathic pain induction and maintenance although the role of many other molecules in neuropathic pain cannot be ruled out [4;8].

It is interesting that overexpression of DRG MZF1 and Kv1.2 AS RNA had distinct effects on AP amplitude and overshoot in DRG neurons. Microinjection of MZF1 siRNA into DRG significantly reduced AP amplitude in large and medium DRG neurons and AP overshot in medium DRG neurons, whereas microinjection of rAAV5-Kv1.2 AS RNA into DRG did not alter either AP amplitude or overshoot in large and medium DRG neurons [44]. The reason for the discrepancy between the effects of MZF1 and Kv1.2 AS RNA is unclear but may be related to the effect of MZF1 on other targets besides Kv1.2 AS RNA. For example, MZF1 as a transcription factor has been reported to also promote the expression of PKCα [17], p55PIK (regulatory subunit of class IA phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase) [8], fibroblast growth factor-2 [24], and matrix metalloproteinase-2 [37]. Action potetial amplitude and overshoot are determined predominantly by sodium channels. Whether and how sodium channels are regulated directly by MZF1 or indirectly by MZF-1-promoted genes is unknown and merits further investigation.

Expression of the transcription factor MZF1, like that of non-transcription factor proteins, can be regulated under neuropathic pain conditions. The present study showed that CCI produced an increase in the level of MZF1 protein in the injured DRG, an observation that is consistent with our previous study in a SNL model [44]. We further demonstrated that CCI also markedly up-regulated the expression of MZF1 mRNA in the injured DRG. This suggests that MZF1 gene transcription is activated in the DRG neurons following peripheral nerve injury. The nerve injury-induced increase in MZF1 mRNA is likely triggered by other transcription factors and/or caused by epigenetic modifications or increases in RNA stability. These possibilities will be addressed in our future studies.

The molecular mechanisms that underlie neuropathic pain genesis are still elusive. A nerve injury-induced increase in spontaneous ectopic activity was detected in injured myelinated afferents (but not unmyelinated fibers) and the corresponding large and medium DRG neurons [23;35]. In human and mouse peripheral axons, the cooling induced bursts of action potentials in myelinated A, but not unmyelinated C-fibers, in oxaliplatin-induced neuropathic pain [34]. Consistently, the use of diphtheria toxin to selectively delete most of mouse small DRG neurons did not affect nerve injury-induced mechanical and thermal pain hypersensitivity [1]. Moreover, substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide in the injured myelinated fibers and in large and medium DRG neurons are significantly increased as early as 2 d after nerve injury [10;41]. It is very likely that the increase in excitability of large and medium DRG neurons drives the release of these neurotransmitters/neuromodulators from their primary afferent terminals and produces spinal central sensitization. The latter contributes to the induction and maintenance of neuropathic pain. This conclusion is supported by the fact that mimicking the CCI-induced increase in DRG MZF1 increased the excitability of large and medium DRG neurons and that blocking this increase attenuated CCI-induced neuropathic pain development and maintenance. MZF1 mRNA is also expressed in small DRG neurons [44]. MZF1 protein may regulate the expression of other genes in addition to Kv1.2 AS RNA gene [9;17;24;37;44]. Although Kv1.2 AS RNA overexpression did not affect the excitability of small DRG neurons [44] and the involvement of small DRG neurons in neuropathic pain is still a puzzle, whether MZF1 in small DRG neurons alters their excitability will be investigated in our future studies.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that blocking the CCI-induced DRG MZF1 increase through microinjection of MZF1 siRNA into the injured DRG impaired pain hypersensitivities during initiation and maintenance of CCI-induced neuropathic pain, without affecting basal/acute nociceptive responses and locomotor function. Mimicking the CCI-induced DRG MZF1 increase through microinjection of rAAV5-MZF1 into the DRGs produced neuropathic pain symptoms. Mechanistically, MZF1 participated in CCI-induced reductions in Kv1.2 mRNA and protein and total potassium current and in the CCI-induced increase in neuronal excitability through MZF1-triggered Kv1.2 AS RNA expression in the injured DRG neurons. Thus, MZF1 is likely an endogenous trigger of neuropathic pain. Microinjection of virus expressing MZF1 siRNA into the injured primary sensory neurons may be a potential strategy for preventing and treating this disorder.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland (NS072206, HL117684, and DA033390) and the Rita Allen Foundation, Princeton, New Jersey.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Y.X.T. and W.Z. conceived the project and supervised most experiments. Z.L., X.G., S.W., L.S., L.L., J.C., B.M.L., A.B., and Y.X.T. designed the project. Z.L. performed the animal model, conducted behavioral experiments, and carried out microinjection. X.G. carried out electrophysiological recording. L.S. performed Western blot and behavioral testing. S.W. performed real-time RT-PCR. L.L., B.M.L., and J.C. were involved in parts of animal model conductance, behavioral testing, or microinjection. Z.L., X.G., S.W., L.S., W.Z. and Y.X.T. analyzed the data. Y.X.T. wrote the manuscript. All of the authors read and discussed the manuscript.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests

References

- 1.Abrahamsen B, Zhao J, Asante CO, Cendan CM, Marsh S, Martinez-Barbera JP, Nassar MA, Dickenson AH, Wood JN. The cell and molecular basis of mechanical, cold, and inflammatory pain. Science. 2008;321:702–705. doi: 10.1126/science.1156916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amaya F, Wang H, Costigan M, Allchorne AJ, Hatcher JP, Egerton J, Stean T, Morisset V, Grose D, Gunthorpe MJ, Chessell IP, Tate S, Green PJ, Woolf CJ. The voltage-gated sodium channel Na(v)1.9 is an effector of peripheral inflammatory pain hypersensitivity. J Neurosci. 2006;26:12852–12860. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4015-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennett GJ, Xie YK. Af peripheral mononeuropathy in rat that produces disorders of pain sensation like those seen in man. Pain. 1988;33:87–107. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90209-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell JN, Meyer RA. Mechanisms of neuropathic pain. Neuron. 2006;52:77–92. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castle NA, London DO, Creech C, Fajloun Z, Stocker JW, Sabatier JM. Maurotoxin: a potent inhibitor of intermediate conductance Ca2+-activated potassium channels. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63:409–418. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.2.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaplan SR, Bach FW, Pogrel JW, Chung JM, Yaksh TL. Quantitative assessment of tactile allodynia in the rat paw. J Neurosci Methods. 1994;53:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(94)90144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chien LY, Cheng JK, Chu D, Cheng CF, Tsaur ML. Reduced expression of A-type potassium channels in primary sensory neurons induces mechanical hypersensitivity. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9855–9865. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0604-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Costigan M, Scholz J, Woolf CJ. Neuropathic pain: a maladaptive response of the nervous system to damage. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2009;32:1–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deng Y, Wang J, Wang G, Jin Y, Luo X, Xia X, Gong J, Hu J. p55PIK transcriptionally activated by MZF1 promotes colorectal cancer cell proliferation. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:868131. doi: 10.1155/2013/868131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devor M. Ectopic discharge in Abeta afferents as a source of neuropathic pain. Exp Brain Res. 2009;196:115–128. doi: 10.1007/s00221-009-1724-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dixon WJ. Efficient analysis of experimental observations. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxical. 1980;20:441–462. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.20.040180.002301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dworkin RH. An overview of neuropathic pain: syndromes, symptoms, signs, and several mechanisms. Clin J Pain. 2002;18:343–349. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200211000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Everill B, Kocsis JD. Nerve growth factor maintains potassium conductance after nerve injury in adult cutaneous afferent dorsal root ganglion neurons. Neuroscience. 2000;100:417–422. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00263-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fan L, Guan X, Wang W, Zhao JY, Zhang H, Tiwari V, Hoffman PN, Li M, Tao YX. Impaired neuropathic pain and preserved acute pain in rats overexpressing voltage-gated potassium channel subunit Kv1.2 in primary afferent neurons. Mol Pain. 2014;10:8. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-10-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fulton S, Thibault D, Mendez JA, Lahaie N, Tirotta E, Borrelli E, Bouvier M, Tempel BL, Trudeau LE. Contribution of Kv1.2 voltage-gated potassium channel to D2 autoreceptor regulation of axonal dopamine overflow. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:9360–9372. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.153262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guan X, Zhu X, Tao YX. Peripheral nerve injury up-regulates expression of interactor protein for cytohesin exchange factor 1 (IPCEF1) mRNA in rat dorsal root ganglion. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2009;380:459–463. doi: 10.1007/s00210-009-0451-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsieh YH, Wu TT, Tsai JH, Huang CY, Hsieh YS, Liu JY. PKCalpha expression regulated by Elk-1 and MZF-1 in human HCC cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;339:217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishikawa K, Tanaka M, Black JA, Waxman SG. Changes in expression of voltage-gated potassium channels in dorsal root ganglion neurons following axotomy. Muscle Nerve. 1999;22:502–507. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4598(199904)22:4<502::aid-mus12>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawasaki Y, Xu ZZ, Wang X, Park JY, Zhuang ZY, Tan PH, Gao YJ, Roy K, Corfas G, Lo EH, Ji RR. Distinct roles of matrix metalloproteases in the early- and late-phase development of neuropathic pain. Nat Med. 2008;14:331–336. doi: 10.1038/nm1723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kerr BJ, Souslova V, McMahon SB, Wood JN. A role for the TTX-resistant sodium channel Nav 1.8 in NGF-induced hyperalgesia, but not neuropathic pain. Neuroreport. 2001;12:3077–3080. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200110080-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim DS, Choi JO, Rim HD, Cho HJ. Downregulation of voltage-gated potassium channel alpha gene expression in dorsal root ganglia following chronic constriction injury of the rat sciatic nerve. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2002;105:146–152. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(02)00388-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim DS, Lee SJ, Cho HJ. Differential usage of multiple brain-derived neurotrophic factor promoter in rat dorsal root ganglia following peripheral nerve injuries and inflammation. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2001;92:167–171. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(01)00154-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu CN, Wall PD, Ben-Dor E, Michaelis M, Amir R, Devor M. Tactile allodynia in the absence of C-fiber activation: altered firing properties of DRG neurons following spinal nerve injury. Pain. 2000;85:503–521. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00251-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luo X, Zhang X, Shao W, Yin Y, Zhou J. Crucial roles of MZF-1 in the transcriptional regulation of apomorphine-induced modulation of FGF-2 expression in astrocytic cultures. J Neurochem. 2009;108:952–961. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lutz BM, Bekker A, Tao YX. Noncoding RNAs: New Players in Chronic Pain. Anesthesiology. 2014;121:409–417. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mao J, Gold MS, Backonja MM. Combination drug therapy for chronic pain: a call for more clinical studies. J Pain. 2011;12:157–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morris JF, Hromas R, Rauscher FJ., III Characterization of the DNA-binding properties of the myeloid zinc finger protein MZF1: two independent DNA-binding domains recognize two DNA consensus sequences with a common G-rich core. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:1786–1795. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.1786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nassar MA, Levato A, Stirling LC, Wood JN. Neuropathic pain develops normally in mice lacking both Na(v)1.7 and Na(v)1.8. Mol Pain. 2005;1:24. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-1-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park JS, Voitenko N, Petralia RS, Guan X, Xu JT, Steinberg JP, Takamiya K, Sotnik A, Kopach O, Huganir RL, Tao YX. Persistent inflammation induces GluR2 internalization via NMDA receptor-triggered PKC activation in dorsal horn neurons. J Neurosci. 2009;29:3206–3219. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4514-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park SY, Choi JY, Kim RU, Lee YS, Cho HJ, Kim DS. Downregulation of voltage-gated potassium channel alpha gene expression by axotomy and neurotrophins in rat dorsal root ganglia. Mol Cells. 2003;16:256–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Priest BT, Murphy BA, Lindia JA, Diaz C, Abbadie C, Ritter AM, Liberator P, Iyer LM, Kash SF, Kohler MG, Kaczorowski GJ, MacIntyre DE, Martin WJ. Contribution of the tetrodotoxin-resistant voltage-gated sodium channel NaV1.9 to sensory transmission and nociceptive behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:9382–9387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501549102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rasband MN, Park EW, Vanderah TW, Lai J, Porreca F, Trimmer JS. Distinct potassium channels on pain-sensing neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:13373–13378. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231376298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singh OV, Yaster M, Xu JT, Guan Y, Guan X, Dharmarajan AM, Raja SN, Zeitlin PL, Tao YX. Proteome of synaptosome-associated proteins in spinal cord dorsal horn after peripheral nerve injury. Proteomics. 2009;9:1241–1253. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sittl R, Lampert A, Huth T, Schuy ET, Link AS, Fleckenstein J, Alzheimer C, Grafe P, Carr RW. Anticancer drug oxaliplatin induces acute cooling-aggravated neuropathy via sodium channel subtype Na(V)1.6-resurgent and persistent current. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:6704–6709. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118058109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tal M, Wall PD, Devor M. Myelinated afferent fiber types that become spontaneously active and mechanosensitive following nerve transection in the rat. Brain Res. 1999;824:218–223. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01190-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tan PH, Yang LC, Shih HC, Lan KC, Cheng JT. Gene knockdown with intrathecal siRNA of NMDA receptor NR2B subunit reduces formalin-induced nociception in the rat. Gene Ther. 2005;12:59–66. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsai SJ, Hwang JM, Hsieh SC, Ying TH, Hsieh YH. Overexpression of myeloid zinc finger 1 suppresses matrix metalloproteinase-2 expression and reduces invasiveness of SiHa human cervical cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;425:462–467. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.07.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Urtikova N, Berson N, Van SJ, Doly S, Truchetto J, Maroteaux L, Pohl M, Conrath M. Antinociceptive effect of peripheral serotonin 5-HT2B receptor activation on neuropathic pain. Pain. 2012;153:1320–1331. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2012.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Visan V, Fajloun Z, Sabatier JM, Grissmer S. Mapping of maurotoxin binding sites on hKv1.2, hKv1.3, and hIKCa1 channels. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;66:1103–1112. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.002774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vorobeychik Y, Gordin V, Mao J, Chen L. Combination therapy for neuropathic pain: a review of current evidence. CNS Drugs. 2011;25:1023–1034. doi: 10.2165/11596280-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weissner W, Winterson BJ, Stuart-Tilley A, Devor M, Bove GM. Time course of substance P expression in dorsal root ganglia following complete spinal nerve transection. J Comp Neurol. 2006;497:78–87. doi: 10.1002/cne.20981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Woolf CJ, Mannion RJ. Neuropathic pain: aetiology, symptoms, mechanisms, and management. Lancet. 1999;353:1959–1964. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01307-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xu JT, Zhao JY, Zhao X, Ligons D, Tiwari V, Atianjoh FE, Lee CY, Liang L, Zang W, Njoku D, Raja SN, Yaster M, Tao YX. Opioid receptor-triggered spinal mTORC1 activation contributes to morphine tolerance and hyperalgesia. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:592–603. doi: 10.1172/JCI70236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhao X, Tang Z, Zhang H, Atianjoh FE, Zhao JY, Liang L, Wang W, Guan X, Kao SC, Tiwari V, Gao YJ, Hoffman PN, Cui H, Li M, Dong X, Tao YX. A long noncoding RNA contributes to neuropathic pain by silencing Kcna2 in primary afferent neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:1024–1031. doi: 10.1038/nn.3438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.