Abstract

Preterm birth is the leading cause of infant morbidity and mortality. Despite extensive research, the genetic contributions to spontaneous preterm birth (SPTB) are not well understood. Term controls were matched with cases by race/ethnicity, maternal age, and parity prior to recruitment. Genotyping was performed using Affymetrix SNP Array 6.0 assays. Statistical analyses utilized PLINK to compare allele occurrence rates between case and control groups, and incorporated quality control and multiple-testing adjustments. We analyzed DNA samples from mother-infant pairs from early SPTB cases (200/7 to 336/7 weeks, 959 women and 979 neonates) and term delivery controls (390/7 to 416/7 weeks, 960 women and 985 neonates). For validation purposes, we included an independent validation cohort consisting of early SPTB cases (293 mothers and 243 infants) and term controls (200 mothers and 149 infants). Clustering analysis revealed no population stratification. Multiple maternal SNPs were identified with association p-values between 10E-5 and 10E-6. The most significant maternal SNP was rs17053026 on chromosome 3 with an odds ratio (OR) 0.44 with a p-value of 1.0E-06. Two neonatal SNPs reached the genome-wide significance threshold, including rs17527054 on chromosome 6p22 with a p-value of 2.7E-12 and rs3777722 on chromosome 6q27 with a p-value of 1.4E-10. However, we could not replicate these findings after adjusting for multiple comparisons in a validation cohort. This is the first report of a genomewide case-control study to identify single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that correlate with SPTB.

Keywords: Obstetric, Premature Birth, Association Analysis

Introduction

Preterm birth (PTB), defined as birth prior to 37 weeks of gestation, is the leading cause of infant morbidity and mortality. In the United States, approximately 11.5% of all births are preterm [Hamilton, et al. 2013], representing approximately 480,000 preterm infants born annually. Although the overall PTB rate has declined slightly in recent years due to a decrease in the rate late PTB (34 – 36 weeks of gestation), the rate of early PTB (20–34 weeks of gestation) has remained constant since 1990. PTB remains a major public health concern due to increased neonatal and infant mortality and both short-term and long-term neonatal morbidity [Hamilton, et al. 2013]. If congenital malformations are excluded, PTB accounts for approximately 70% of all neonatal deaths and nearly 50% of long-term neurological problems [Hack and Fanaroff 1993; Kramer, et al. 2000; Mathews, et al. 2004; Wood, et al. 2000]. These long-term neurological problems include serious physical and mental disabilities such as cerebral palsy, developmental delay, vision and hearing loss, and chronic lung disease. In 2005, the economic cost for PTB was $26.2 billion in the U.S. [Institute of Medicine 2007]. Most of the infant mortality and morbidity resulting from PTB are associated with the 2% of infants born early preterm (birth at less than 32 weeks gestation) [Martin, et al. 2005].

Despite decades of research, the heterogeneous nature of PTB has made it difficult to study the underlying causes and genetic predisposition of PTB. Approximately 25–30% of PTBs are medically indicated as a result of maternal medical or obstetrical complications. The remaining cases of PTBs are due to spontaneous preterm birth (SPTB). While SPTB is typically attributed to either spontaneous fetal membrane rupture or spontaneous onset of uterine contractions, this is likely an oversimplification. Studies have demonstrated that multiple mechanisms, and risk factors converge to produce a similar end result— preterm parturition. Intrauterine inflammation, genital tract microbial colonization/infection, uterine bleeding, excessive uterine stretch, maternal psychosocial stress, and fetal physiological stress all contribute to SPTB [Institute of Medicine 2007]. Thus, there is a need for better mechanistic insight, mechanism-based classification and risk prediction of SPTB.

Family studies and twin studies have suggested that genetic factors may contribute to about 40 percent of PTBs [Svensson, et al. 2009]. Numerous candidate gene studies have investigated the genetics of SPTB, with investigators demonstrating associations between SPTB and maternal single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in a number of genes believed to be important in diverse SPTB pathways (see [Crider, et al. 2005] and [Giarratano 2006] for examples). To date, however, these candidate gene approaches have had poor reproducibility and a limited impact on our understanding of SPTB. Genomewide association studies (GWAS) have been shown to successfully identify genetic associations with complex traits. This approach can be used to validate previously observed associations and/or to identify new and unexpected associations [Manolio 2010]. One of the largest SPTB genetic studies to date is a candidate gene analysis that examined 426 SNPs for 55 genes in 300 women with SPTB (delivered less than 37 weeks) and 458 term controls in a multi-ethnic population [Hao, et al. 2004]. A limitation of this study was that the population was skewed towards late SPTB, and thus has uncertain relevance to early SPTB. Additionally, only maternal genotype and its association with the SPTB phenotype was examined.

Although other medical conditions with major public health burdens have been the targets of numerous high-throughput genomic analyses [Manolio 2010], these techniques have not been widely utilized for the investigation of SPTB. Moreover, two genetically unique individuals—mother and fetus—contribute to the physiology of normal pregnancy and delivery, and plausibly also to the pathophysiology of SPTB. Thus, the Genomic and Proteomic Network for Preterm Birth Research undertook a large prospective case-control study to determine if early SPTB is associated with specific maternal and fetal genetic polymorphisms.

Materials and Methods

The Genomic and Proteomic Network (GPN) for Preterm Birth Research is composed of three primary clinical sites (University of Alabama at Birmingham, University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, and University of Utah), a laboratory core (University of Pennsylvania), a data management, statistics, and informatics core (Yale University), NICHD, and a steering committee chair.

Study Design

We conducted a case-control study to examine genetic associations with SPTB occurring at less than 34 weeks of gestation. We subsequently formed an independent validation cohort with similar phenotype data.

Subjects

A total of 7,215 subjects were screened, 2,072 consented, and 2,040 found eligible. Participants were recruited at each of the three major clinical sites (see above) as well as at additional sites—University of North Carolina, Brown University, Columbia University, the University of Texas – Houston, and Northwestern University—added during the course of the study to enhance recruitment. The protocol was approved by the institutional review board of each participating institution, and a signed informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Cases were defined as women with viable singleton pregnancies between 20 weeks 0 days and 33 weeks 6 days (inclusive) who experienced the spontaneous onset of labor. Controls were defined as women with deliveries between 39 weeks 0 days and 41 weeks 6 days following the spontaneous onset of labor and delivery. The spontaneous onset of labor was defined as either 4 or more contractions in a 20-minute interval or 10 contractions in an hour, along with cervical dilation of at least 2 cm with either documented interval cervical change of 1 cm or cervical effacement of at least 75%. Women with pregnancies complicated by polyhydramnios, uterine anomalies, cervical cerclage, or a fetus with known aneuploidy or lethal anomaly were excluded. In addition, controls with a history of PTB in any prior pregnancy were excluded. Women who presented with premature membrane rupture were eligible for study participation only if they labored spontaneously and delivered before 34 weeks gestation. Whenever possible, cases were 1:1-matched with controls at each site according to race/ethnicity, maternal age (<20, 20–29, 30–39, ≥40 years), and parity (primigravid/multigravid). Gestational age (GA) was determined according to a previously described algorithm [Carey, et al. 2000].

Samples

EDTA-stabilized maternal and umbilical cord blood samples were archived at −20°C within 24 hours of collection. If a blood sample was not available, saliva for DNA extraction was collected using Oragene OG-300 kits (DNA Genotek, Ontario). All samples were stored at −20°C until shipment to the core laboratory.

We obtained DNA samples from an independent replication cohort of 493 mothers who had no history of preterm delivery (before 37 weeks of gestation) before the current pregnancy. Among them, 293 delivered early preterm infants (gestational age at delivery < 34 week) and 200 delivered at term. Purified DNA or serum samples from this cohort were provided by two other NICHD-funded networks [Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network (MFMU) and Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network (SCRN)]. Serum extractions and DNA quality control were conducted as for the GWAS cohort (below).

Genotyping

Genomewide (cases and controls) and targeted (validation study) SNP genotyping was conducted in the University of Pennsylvania Molecular Profiling Facility. The Genome-wide Human SNP Array 6.0 (Affymetrix, Santa Clara CA) assays were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions using GeneChip Fluidics 450 Stations and a GeneChip 3000 7G Scanner. Microarray quality control parameters and genotype calls were generated with Affymetrix Genotyping Console v4.1 software.

For the validation cohort, a panel of 96 SNPs was selected from the genomewide analysis for targeted genotyping to fit in the 96-well format. Highly parallel quantitative PCR using SNP type Assays and 96.96 Dynamic Arrays (Fluidigm, South San Francisco CA) was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocols.

Data Quality Control (QC)

Samples were evaluated to ensure that genotyping information were consistent with reported gender. Discrepancies prompted either further review of clinical data to ensure no entry errors or exclusion of the subject from further analysis if the discrepancy could not be resolved. Identical by descent (IBD) was estimated between each pair of samples. Samples with high pairwise IBD (>0.9) were removed due to potential contamination. Mother-infant pairs were checked using IBD sharing probability of 1 allele (Z1 score by PLINK). Pairs with Z1<0.7 and non-pairs with Z1>0.7 were removed. We performed the gender check using PLINK v1.07 [Purcell; Purcell, et al. 2007] by computing the heterozygosity rates on X chromosome data.

The exclusion thresholds for sample and SNP call rates were 95% for maternal data and 90% for neonatal data. Because the neonatal genotype data have an overall lower quality than the maternal genotype data, we used a lower call rate threshold for these data thus avoiding the removal of an excessive number of SNPs. SNPs were removed if their minor allele frequencies were below 0.01 or if they failed the Hardy-Weinberg disequilibrium test at the significance level of 0.0001 in controls. We performed clustering and multidimensional scaling analyses based on the pairwise identity-by-state distance in PLINK v1.07 to assess population stratification.

We tested for potential Mendelian errors in the genotypes by identifying incompatible genotypes between a mother and her infant. Four mother-infant pairs showed such errors at rates greater than 0.1. Hence, these four infant subjects were removed from the neonatal data.

Maternal QC

For maternal data, 1,920 individuals were attempted to be genotyped, and 1,919 individuals (959 cases and 960 controls) were successfully genotyped. The overall call rate is 99.4%. After check pairwise IBD, 10 individuals (6 cases and 4 controls) were removed for high IBD, and 26 individuals (17 cases and 9 controls) were removed for inconsistent mother-infant relationship. After QC, 17,148 SNPs and 2 individuals (1 cases and 1 control) were excluded for low call rates. 15,483 SNPs with low minor allele frequencies and 96,260 SNPs exceeding the Hardy-Weinberg disequilibrium cutoff were excluded. After these quality control steps, 935 cases, 946 controls, and 779,326 SNPs remained and were included in the statistical analysis.

Neonatal QC

For neonatal data, 1,967 individuals were attempted to be genotyped and 1,964 individuals (979 cases and 985 controls) were successfully genotyped. The overall call rate is 97.4%. After checking IBD, 6 individuals (all cases) were removed for high IBD, and 25 individuals (16 cases and 9 controls) were removed for inconsistent mother-infant relationship. After checking for gender discrepancies and Mendelian errors, 24 individuals (12 cases and 12 controls) were removed (20 for gender discrepancies, 2 for high Mendelian errors and 2 for both). After QC, 33,622 SNPS and 58 individuals (29 cases and 29 controls) were removed for low call rates, and 16,548 SNPs were removed for minor allele frequencies below 1%. We excluded 65,288 SNPs in the neonatal data for failing the Hardy-Weinberg disequilibrium test. Analysis of neonatal genotypes was performed on 916 cases, 935 controls, and 797,196 SNPs after all of the QC steps.

MFMU and SCRN Validation Cohort QC

We obtained genotypes from the 493 mothers for 96 targeted SNPs, and their 243 early SPTB or 149 term infants in the validation cohort. All reported assays passed the 95% call rate threshold.

Validation Cohort with History of PTB QC

We genotyped (Affymetrix SNP 6.0) a longitudinal cohort of 329 women with a history of PTB at 37 weeks of gestational age. QC parameters for GWAS and phenotypic data were measured using the same study protocol as for the maternal and neonatal samples described above.

Clinical Data and Phenotypes

Demographics and outcomes data were collected by certified research nurses through chart reviews and patient interviews. Extensive demographic data and medical, social and obstetric histories were obtained. Detailed information on all prior pregnancies was collected as were data on the current pregnancy, including any signs of preterm labor, evaluation for pregnancy complications, and medication use. Information on the delivery of the current pregnancy, including neonatal outcomes, was also abstracted. In addition, detailed data on family history of preterm birth were collected.

Statistical Analysis

After the quality control procedure, we performed logistic regression tests on the dataset in PLINK v1.07. Age group, race, study site, and parity were considered as confounders to remove potential bias. Specifically, age was grouped into four categories (<20, 20–29, 30–39, and >39), and race and ethnicity were also grouped into four categories (Hispanic, Non-Hispanic white, Non-Hispanic black, and other). We obtained the quantile-quantile plots of the test statistic, and calculated the inflation factor λ to assess the quality of case-control matching and the genotyping heterogeneity between cases and controls.

Gene-based association analyses were also performed to account for the fact that there are more SNPs than genes and that SNPs can cluster within or around a specific gene. Therefore, if there are multiple SNPs within a gene that display an association, the gene-based analysis provided a way to consider the effect of variation within the gene as a whole. For maternal data, we used PLINK v1.07 to examine the top 20 SNPs. For the neonatal data, these analyses were conducted using Knowledge-Based Mining System for Genome-wide Genetic Studies (KGG, version 2.0) based on the association test results and linkage disequilibrium files obtained from PLINK v1.07.

We reported the p-values without adjustments for multiple comparisons. However, when we state a potentially significant association, the threshold for the level of significance is determined after using the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

Results

Maternal Data

Table 1 summarizes relevant demographic variables including maternal age, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, income, and insurance type. Women in the case group were less likely to be married and to have private insurance than were those in the control group. Table 2 compares obstetric outcomes in cases and controls. As expected, the cases had significantly (p<0.05) more complications in preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, chorioamnionitis and abruption than the controls.

Table 1.

Demographic variables of the maternal cohort

| Variables | Cases (N=1025) | Controls (N=1015) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age, years | 25.6 (6.0) | 25.7 (5.6) | 0.61 |

| Maternal race | |||

| Caucasian | 696 (67.9) | 690 (68.0) | 0.72 |

| African American | 234 (22.8) | 225 (22.2) | |

| Other | 95 (9.3) | 100 (9.8) | |

| Maternal Hispanic ethnicity | 210 (20.5) | 206 (20.3) | 0.96 |

| Paternal race | |||

| Caucasian | 675 (65.9) | 654 (64.4) | 0.99 |

| African American | 241 (23.5) | 244 (24.0) | |

| Other | 109 (10.6) | 117 (11.6) | |

| Paternal Hispanic ethnicity | 223 (21.8) | 222 (21.9) | 0.99 |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married, living with partner | 511 (49.9) | 577 (56.8) | |

| Divorced/widowed/separated, living w/partner | 19 (1.9) | 14 (1.4) | |

| Divorced/widowed/separated, NOT living w/partner | 26 (2.5) | 11 (1.1) | 0.007 |

| Never married, living with partner | 217 (21.2) | 187 (18.4) | |

| Never married, NOT living with partner | 250 (24.4) | 226 (22.3) | |

| Unknown or Missing | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Maternal education, highest level completed | |||

| Elementary school (K-5) | 8 (0.8) | 5 (0.5) | |

| Middle school (6–8) | 86 (8.4) | 71 (7.0) | 0.13 |

| High school / GED (9–12) | 514 (50.1) | 478 (47.1) | |

| College (13–16) | 411 (40.1) | 456 (44.9) | |

| Unknown or Missing | 6 (0.6) | 5 (0.5) | |

| Household income | |||

| $0 – $12,000 | 180 (17.6) | 169 (16.7) | |

| $12,001 – $24,000 | 163 (15.9) | 171 (16.8) | |

| $24,001 – $50,000 | 186 (18.1) | 176 (17.3) | 0.16 |

| $50,001 – $100,000 | 125 (12.2) | 161 (15.9) | |

| >$100,001 | 53 (5.2) | 70 (6.9) | |

| Unknown or declined to answer | 318 (31.0) | 268 (26.4) | |

| Insurance type | |||

| None/self-pay | 81 (7.9) | 57 (5.6) | |

| Public | 559 (54.5) | 530 (52.2) | 0.06 |

| Private | 382 (37.3) | 425 (41.9) | |

| Other | 2 (0.2) | 3 (0.3) | |

| Unknown or Missing | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

For numerical variables, the mean and the standard deviation (in parentheses) are listed; differences were tested using t-test. For categorical variables, the numbers of subjects and the corresponding percentages (in parentheses) are listed; and the differences tested using chi-squared test or using Fisher’s exact test if the observed value in any cell of the contingency table was less than 10.

Table 2.

Obstetric variables of the maternal cohort

| Delivery Status | Cases (n=1025) | Controls (n=1015) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preeclampsia | 16 (1.6) | 4 (0.4) | 0.01 |

| Gestational diabetes | 82 (8.0) | 21 (2.1) | <0.001 |

| Oligohydramnios | 43 (4.2) | 5 (0.5) | <0.001 |

| Chorioamnionitis | 72 (7.0) | 27 (2.7) | <0.001 |

| Suspected abruption | 84 (8.2) | 1 (0.1) | <0.001 |

| Gestational age at membrane rupture, weeks | 29.7 (3.4) | 39.9 (1.3) | <0.001 |

| Delivery gestational age, weeks | 30.0 (3.2) | 39.9 (0.6) | <0.001 |

| Birthweight, grams | 1536 (571) | 3427 (390) | <0.001 |

| Cesarean delivery | 243 (23.7) | 78 (7.7) | <0.001 |

| Male fetus | 571 (55.7) | 513 (50.5) | 0.02 |

| NICU admission | 1003 (97.9) | 32 (3.2) | <0.001 |

The numbers of infants and the corresponding percentages (in parentheses) are listed; and the differences were tested using chi-squared test or using Fisher’s exact test if the observed value in any cell of the contingency table was less than 10.

Table 3 lists the top 20 maternal SNPs with smallest p-values from the association tests. The most significant SNP was rs17053026 on chromosome 3, exhibiting an odds ratio (OR) of 0.44. This SNP is located in the region of the DCP1A gene which encodes an RNA decapping enzyme that plays a role in transcription regulation. Also noted among the top 20 maternal SNPs are 4 SNPs on chromosome 8p21.1 that are located in the CCDC25 gene, with ORs ranging from 1.53 to 1.60. While the function of this gene is poorly understood, it appears to be highly conserved across species. Another SNP, rs12066169, is located near the PAX7 gene on chromosome 1p36.13, and has a high OR of 5.22. PAX7 is a member of the paired box family of transcription factors, and involves in the fetal development and cancer growth.

Table 3.

Top 20 maternal SNPs from the genomewide association study

| Chr. | SNP | Map Coordinate* | Minor Allele | MAF | P-value | OR | Gene |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | rs17053026 | 53418798 | T | 0.05 | 1.0E-06 | 0.44 | DCP1A |

| 12 | rs12830013 | 16677532 | T | 0.21 | 1.1E-06 | 1.52 | LMO3 |

| 4 | rs17001970 | 77370038 | T | 0.08 | 5.6E-06 | 1.80 | SHROOM3 |

| 9 | rs501631 | 3943125 | T | 0.48 | 5.9E-06 | 1.37 | GLIS3 |

| 8 | rs6989497 | 27612891 | A | 0.12 | 6.2E-06 | 1.60 | CCDC25 |

| 8 | rs6987111 | 27600450 | A | 0.12 | 8.0E-06 | 1.58 | CCDC25 |

| 8 | rs7823365 | 27601594 | A | 0.12 | 1.0E-05 | 1.57 | CCDC25 |

| 2 | rs12995518 | 50880025 | T | 0.36 | 1.1E-05 | 1.36 | NRXN1 |

| 5 | rs2047075 | 4109621 | C | 0.43 | 1.4E-05 | 1.35 | IRX1 |

| 17 | rs7211542 | 4374569 | C | 0.13 | 2.1E-05 | 1.51 | SPNS3 |

| 8 | rs6989156 | 27604550 | C | 0.13 | 2.2E-05 | 1.53 | CCDC25 |

| 17 | rs17746268 | 63315317 | A | 0.08 | 2.6E-05 | 1.65 | RGS9 |

| 4 | rs6858750 | 56090836 | A | 0.04 | 2.7E-05 | 0.46 | LOC100128865 |

| 22 | rs737627 | 45259574 | A | 0.03 | 3.0E-05 | 2.44 | PHF21B |

| 10 | rs6480306 | 69935235 | T | 0.02 | 3.3E-05 | 3.14 | MYPN |

| 8 | rs9314355 | 27699168 | T | 0.11 | 3.3E-05 | 1.56 | PBK |

| 1 | rs12066169 | 19070568 | T | 0.01 | 3.3E-05 | 5.22 | PAX7 |

| 12 | rs11046680 | 23042553 | A | 0.05 | 3.7E-05 | 1.95 | ETNK1 |

| 10 | rs17531466 | 36350381 | T | 0.06 | 4.0E-05 | 1.86 | FZD8 |

| 11 | rs1025888 | 99747329 | C | 0.48 | 4.1E-05 | 1.32 | CNTN5 |

Genome build GRCh37

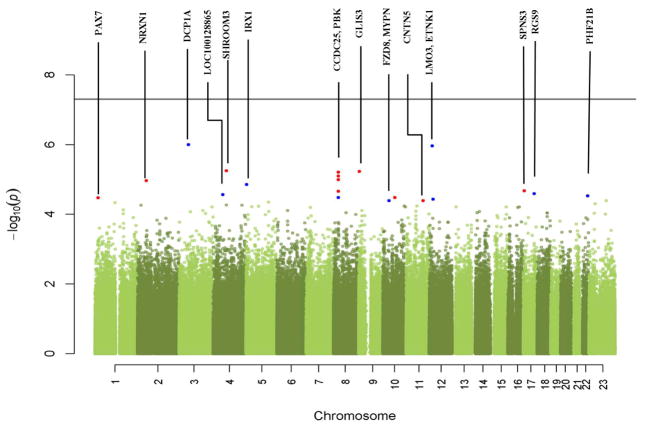

Figure 1 presents a Manhattan plot for the overall maternal genomewide analysis. None of the SNPs reached the genomewide significance threshold (5E-8). Interestingly gene CCDC25 appears to contain the greatest number of SNPs with the smallest p-values. We also performed a gene-based analysis (Guo et al. 2013). The lowest p-value of the gene-based analysis was in the order of 10−3. The most significant genes are CCDC25, TMEM2, and MYPN. Among them, CCDC25 overlaps with the top SNPs rs6989497, rs6987111, rs7823365, and rs6989156, and MYPN overlaps with the top SNP rs6480306.

Figure 1. Manhattan plot from the maternal genome-wide association tests.

The -log10(p-value) of each SNP from the association test is plotted relative to its position on each chromosome. Red dots represent top candidate SNPs within known genes (labeled). Blue dots represent top SNPs near known genes. The horizontal line indicates the threshold for genome-wide significance (5E-8).

Neonatal Data

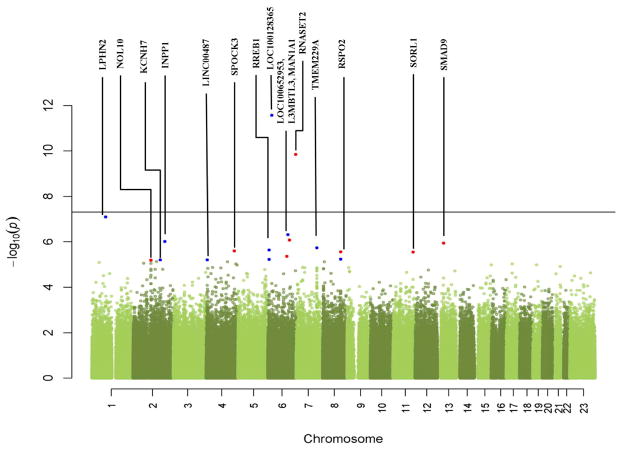

Table 4 lists the top 20 neonatal SNPs with smallest p-values from the association tests. Figure 2 is the Manhattan plot of these data. In contrast to the maternal GWAS data, two neonatal SNPs passed the genome-wide significance threshold. The most significant neonatal SNP was rs17527054 on chromosome 6p22 with a p-value of 2.7E-12. This SNP is located in the area of the major histocompatability complex. The second-most significant neonatal SNP, with a p-value of 1.4E-10, was rs3777722, located in the RNASET2 gene in the chromosome 6q27 region. This gene encodes a ribonuclease, and its variants have been associated with malignancies and leukoencephalopathy. Other SNPs of interest, although not reaching the threshold of significance, include rs184270 (OR of 2.49) and rs563538 (OR of 2.47). SNP rs184270 is located close to the KCNH7 gene on chromosome 2, which encodes a member of the potassium voltage-gated channel, subfamily H. SNP rs563538 is located in the SMAD9 gene on chromosome 13. This gene is a member of the SMAD family, which transduces signals from TGF-β family members. Three of the top 20 SNPs, all with OR of 0.72, are located in the NOL10 gene on chromosome 2p25.1, which encodes a nucleolar protein and is highly conserved across species. Two of the 20 SNPs, rs16877149 and rs11780793, both with OR 0.67, are located respectively in and close to the RSPO2 gene on chromosome 8q23.1, which encodes a secreted protein. Another two of the 20 SNPs, rs560131 and rs3863225, with OR of 1.41 and 1.38, are located close to the RREB1 gene, which encodes a zinc finger transcription factor. Another intragenic SNP, rs4429972, is located in the L3MBTL3 gene on chromosome 6. The function of this gene is not fully known but several studies demonstrated an association with height. SNP rs11892526 on chromosome 2 is located close to the INPP1 gene. This gene encodes the enzyme inositol polyphosphate-1-phosphatase. The lowest p-value of gene-based analysis was in the order of 10−9. The most significant genes are RNASET2, MFSD6, and L3MBTL3. Among them, RNASET2 overlaps with the top SNP rs3777722, and L3MBTL3 overlaps with the top SNP rs4429972.

Table 4.

Top 20 neonatal SNPs obtained from the genomewide association study

| Chr. | SNP | Map Coordinate * | Minor Allele | MAF | P-value | OR | Gene |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | rs17527054 | 23925921 | G | 0.08 | 2.7E-12 | 0.39 | LOC100128365 |

| 6 | rs3777722 | 167352104 | A | 0.21 | 1.4E-10 | 0.57 | RNASET2 |

| 1 | rs480745 | 83269970 | A | 0.09 | 8.0E-08 | 0.51 | LPHN2 |

| 6 | rs2794256 | 119943401 | A | 0.27 | 4.8E-07 | 1.48 | MAN1A1 |

| 6 | rs4429972 | 130395304 | T | 0.03 | 8.3E-07 | 0.33 | L3MBTL3 |

| 2 | rs11892526 | 191255883 | C | 0.23 | 9.7E-07 | 0.65 | INPP1 |

| 13 | rs563538 | 37433721 | T | 0.04 | 1.1E-06 | 2.47 | SMAD9 |

| 7 | rs17553718 | 123731276 | G | 0.31 | 1.8E-06 | 0.69 | TMEM229A |

| 6 | rs560131 | 7047411 | G | 0.41 | 2.3E-06 | 1.41 | RREB1 |

| 4 | rs17703512 | 168137719 | C | 0.28 | 2.5E-06 | 0.69 | SPOCK3 |

| 8 | rs16877149 | 109090197 | A | 0.21 | 2.8E-06 | 0.67 | RSPO2 |

| 11 | rs10892761 | 121497884 | C | 0.36 | 2.8E-06 | 0.71 | SORL1 |

| 6 | rs6927568 | 114025900 | A | 0.03 | 4.4E-06 | 0.35 | LOC100652953 |

| 8 | rs11780793 | 109154752 | T | 0.19 | 5.7E-06 | 0.67 | RSPO2 |

| 6 | rs3863225 | 7032317 | A | 0.41 | 5.9E-06 | 1.38 | RREB1 |

| 2 | rs184270 | 163710934 | T | 0.03 | 6.2E-06 | 2.49 | KCNH7 |

| 4 | rs13130860 | 6530193 | G | 0.27 | 6.2E-06 | 0.70 | LINC00487 |

| 2 | rs1651151 | 108083239 | G | 0.30 | 6.4E-06 | 0.72 | NOL10 |

| 2 | rs266174 | 108050854 | A | 0.30 | 6.5E-06 | 0.72 | NOL10 |

| 2 | rs266236 | 108078636 | G | 0.30 | 6.5E-06 | 0.72 | NOL10 |

Genome build GRCh37

Figure 2. Manhattan plot from the neonatal genome-wide association tests.

The -log10(p-value) of each SNP from the association test is plotted relative to its position on each chromosome. Red dots represent top candidate SNPs within known genes (labeled). Blue dots represent top SNPs near known genes. The horizontal line indicates the threshold for genome-wide significance (5E-8).

Validation Data

Table 5 describes the main demographic variables for the maternal validation cohort. Similarly, Table 6 describes the demographic variables for the neonatal validation cohort. We found no significant difference between cases and controls in both cohorts for demographic variables including maternal age, race and ethnicity, and parity.

Table 5.

Demographic variables of the maternal validation cohort

| Variables | Cases (N=293) | Controls (N=200) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study source | |||

| MFMU | 215 (73.4) | 121 (60.5) | 0.004 |

| SCRN | 78 (26.6) | 79 (39.5) | |

| Maternal age, years | 24.6 (6.0) | 24.4 (5.6) | 0.66 |

| Maternal race/ethnicity | |||

| Caucasian | 66 (22.5) | 37 (18.5) | |

| African American | 110 (37.5) | 84 (42.0) | 0.68 |

| Hispanic | 110 (37.5) | 74 (37.0) | |

| Other | 7 (2.4) | 5 (2.5) | |

| Maternal parity | |||

| Nulliparous | 98 (33.4) | 64 (32.0) | 0.81 |

| Multiparous | 195 (66.6) | 136 (68.0) | |

Table 6.

Demographic variables of the neonatal validation cohort

| Variables | Cases (N=243) | Controls (N=149) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study source | |||

| MFMU | 220 (90.5) | 90 (60.4) | <0.001 |

| SCRN | 23 (9.5) | 59 (39.6) | |

| Maternal age, years | 23.9 (5.8) | 24.5 (5.7) | 0.34 |

| Maternal race/ethnicity | |||

| Caucasian | 60 (24.7) | 23 (15.4) | |

| African American | 98 (40.3) | 57 (38.3) | 0.07 |

| Hispanic | 81 (33.3) | 66 (44.3) | |

| Other | 4 (1.6) | 3 (2.0) | |

| Maternal parity | |||

| Nulliparous | 82 (33.7) | 47 (31.5) | 0.73 |

| Multiparous | 161 (66.3) | 102 (68.5) | |

Table 7 presents the validation results for 14 of the top 20 SNPs obtained from the maternal GWAS. None of the top candidate SNPs were found to be significantly associated with SPTB in the validation cohort. SNP rs17746268 exhibited a raw p-value of 0.03, but its corresponding OR in the replication cohort was in the opposite direction to the OR in the GWAS cohort.

Table 7.

Odds ratios and p-values for 14 of the top 20 maternal SNPs measured in the validation cohort and combined with the initial GWAS

| SNP | OR Replication | P-value Replication | OR Combined | P-value Combined |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs17053026 | 0.88 | 0.61 | 0.53 | 4.9E-06 |

| rs17001970 | 0.89 | 0.52 | 1.43 | 7.5E-04 |

| rs501631 | 1.13 | 0.44 | 1.33 | 6.7E-06 |

| rs6989497 | 0.81 | 0.29 | 1.38 | 4.7E-04 |

| rs7823365 | 0.84 | 0.37 | 1.37 | 4.9E-04 |

| rs2047075 | 1.02 | 0.91 | 1.27 | 1.1E-04 |

| rs7211542 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.43 | 8.0E-05 |

| rs6989156 | 1.06 | 0.77 | 1.41 | 1.1E-04 |

| rs17746268 | 0.52 | 0.03 | 1.41 | 1.6E-03 |

| rs6858750 | 0.94 | 0.86 | 0.55 | 1.4E-04 |

| rs737627 | 0.74 | 0.18 | 1.43 | 1.7E-02 |

| rs9314355 | 0.98 | 0.93 | 1.42 | 2.5E-04 |

| rs12066169 | 0.80 | 0.35 | 1.43 | 5.1E-02 |

| rs1025888 | 1.19 | 0.22 | 1.29 | 3.0E-05 |

Table 8 presents the validation results for 14 of the top 20 SNPs from the neonatal GWAS. SNP rs3863225 produced a p-value of 0.05 but its ORs were in opposite directions in the GWAS and replication neonatal cohorts.

Table 8.

Odds ratios and p-values for 14 of the top 20 neonatal SNPs measured in the replication cohort and combined with the initial GWAS

| SNP | OR Replication | P-value Replication | OR Combined | P-value Combined |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs3777722 | 1.04 | 0.87 | 0.61 | 1.3E-09 |

| rs480745 | 1.14 | 0.69 | 0.57 | 6.7E-07 |

| rs2794256 | 0.99 | 0.94 | 1.39 | 4.5E-06 |

| rs11892526 | 1.31 | 0.20 | 0.72 | 4.6E-05 |

| rs563538 | 1.20 | 0.56 | 2.05 | 7.7E-06 |

| rs560131 | 0.87 | 0.44 | 1.31 | 6.3E-05 |

| rs17703512 | 1.07 | 0.75 | 0.74 | 2.0E-05 |

| rs10892761 | 0.89 | 0.53 | 0.73 | 3.3E-06 |

| rs11780793 | 0.98 | 0.93 | 0.69 | 1.0E-05 |

| rs3863225 | 0.69 | 0.05 | 1.25 | 6.6E-04 |

| rs184270 | 0.95 | 0.90 | 2.14 | 3.1E-05 |

| rs13130860 | 1.20 | 0.40 | 0.75 | 9.6E-05 |

| rs1651151 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.75 | 2.0E-05 |

| rs266236 | 1.07 | 0.70 | 0.76 | 4.8E-05 |

Validation Cohort of Women with History of PTB

All women in this cohort had a history of PTB. The racial distribution was 195 (59.3%) Caucasian, 105 (31.9%) African American, and 29 (8.8%) others; 83 (25.2%) have Hispanic or Latino ethnicity. Mean maternal age was 27.6 ± 5.2. Because we lacked controls for this cohort, association tests were not performed. We instead examined allele frequencies for the top SNPs identified by GWAS, with the rationale that an allele associated with PTB may occur with a frequency in this cohort that is closer to that of the GWAS SPTBs than observed in controls.

Table 9 compares the allele frequencies among maternal samples in the GWAS cases, GWAS controls, MFMU/SCRN replication cases, MFMU/SCRN replication controls, and validation cohort with history of PTB. Similarly, Table 10 compares the allele frequencies among neonatal samples in the GWAS cases, GWAS controls, MFMU/SCRN replication cases, and MFMU/SCRN replication controls. The allele frequency patterns observed did not appear consistent.

Table 9.

Comparison of MAFs in cases, controls, replication cases, replication controls, and validation cohort with history of PTB for 14 of the top 20 maternal SNPs

| SNP | Case | Control | Case replication | Control replication | Cohort with history |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs17053026 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.03 |

| rs17001970 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.21 | 0.08 |

| rs501631 | 0.51 | 0.44 | 0.56 | 0.56 | 0.51 |

| rs6989497 | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.14 |

| rs7823365 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.14 |

| rs2047075 | 0.47 | 0.40 | 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.45 |

| rs7211542 | 0.16 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.10 |

| rs6989156 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.16 |

| rs17746268 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.08 |

| rs6858750 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.04 |

| rs737627 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.04 |

| rs9314355 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.12 |

| rs12066169 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.02 |

| rs1025888 | 0.52 | 0.45 | 0.52 | 0.48 | 0.52 |

Table 10.

Comparison of MAFs in cases, controls, replication cases and replication controls for 14 of the top 20 neonatal SNPs

| SNP | Case | Control | Case replication | Control replication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs3777722 | 0.16 | 0.26 | 0.14 | 0.17 |

| rs480745 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.07 |

| rs2794256 | 0.31 | 0.23 | 0.26 | 0.27 |

| rs11892526 | 0.19 | 0.26 | 0.30 | 0.28 |

| rs563538 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.07 |

| rs560131 | 0.45 | 0.38 | 0.33 | 0.34 |

| rs17703512 | 0.25 | 0.32 | 0.20 | 0.18 |

| rs10892761 | 0.32 | 0.40 | 0.26 | 0.29 |

| rs11780793 | 0.16 | 0.22 | 0.13 | 0.13 |

| rs3863225 | 0.44 | 0.38 | 0.31 | 0.36 |

| rs184270 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| rs13130860 | 0.24 | 0.30 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

| rs1651151 | 0.27 | 0.33 | 0.29 | 0.31 |

| rs266236 | 0.26 | 0.33 | 0.30 | 0.30 |

Discussion

To identify genetic changes that might underlie heightened risk for preterm birth, we performed GWAS analyses on large sets of well- characterized maternal and neonatal data. Our data show that no maternal SNPs achieved a genomewide significance level, but several neonatal SNPs passed the genome-wide threshold. Using an independent cohort, we found that none of the results were conclusive. No overlap was found between the top 10 maternal and neonatal SNP sets.

A main strength of our study is that it is based on a large cohort of carefully phenotyped, clinically-significant early SPTB cases and matched controls. We employed a strict protocol and documented in a detailed manual of operation strict definitions of preterm labor, PPROM as well other important covariates to allow for uniform ascertainment across sites and ensure well phenotyped cases of early SPTB. The cohort is ethnically/racially and any relevant findings have the potential to be broadly applicable, but genetic diversity may also confound association tests. We used a series of quality control steps including data and sample validation by multiple teams within the GPN to ensure the quality of genotypes and phenotypes, and removed data that did not meet commonly accepted quality thresholds. Furthermore, we gathered an independent cohort that met the same inclusion and exclusion criteria. Despite these strengths, the significant SNPs discovered in our GWAS cohort were not replicated in the validation cohort. Although we defined the primary outcome carefully to improve the power of our study, it may improve the power further to further consider the heterogeneity of preterm delivery and refine the outcome definition.

Our case-control study was powered to detect an OR of 2.0 or greater. However, SPTB is a complex syndrome, reflecting interacting genomic and non-genomic factors and potentially rare genetic variants. Since this may mean that any one, or few genes, have a relatively small individual effect on SPTB this could be a major reason that we did not detect any significant SNP in the analysis of maternal and neonatal data. While we obtained an independent cohort from reliable resources, it was likely too small to confirm a relatively small OR, especially after adjusting for the number of tested SNPs.

In light of our overall negative findings, we believe that there is a need to increase the statistical power by pooling together a larger cohort using a meta-analysis approach. Enlarging the sample population may reveal some statistically significant SNPs, but the likelihood of measuring a greater effect (e.g. OR) is low, because our cohort is large enough to provide a rather accurate point estimate of the effect size. Therefore, while the chance that a much larger GWAS would contribute to our understanding of SPTB is not expected to be high, a meta-analysis approach may allow for identification of genetic variants with smaller effect sizes than we had the power to interrogate in our cohort. In addition, we analyzed maternal and neonatal SNPs separately. It might be helpful to examine potential maternal-neonatal gene interactions, and such data may be used to interrogate potential functional pathways that might shed light on the process of SPTB. We believe this is an important effort although it is beyond the scope of this report.

While the genetic variants with the highest significance levels did not replicate in our validation cohorts, many of the top SNPs we identified were located in genes or genomic regions involved in pathways that have been previously implicated in preterm birth, such as inflammation and immunity, or play a significant role in overall gene expression. This further highlights the fact that while variation in one gene alone is unlikely to have a major impact in the occurrence of SPTB, variation in several genes could lead to a different cascade of events or result in a significant alteration of epistatic effects. Therefore, analysis of gene-gene and gene-environment interactions might reveal clinically relevant associations.

In summary, despite the fact that we conducted the largest GWAS study of SPTB in an extremely well characterized and high-risk case group, our study failed to identify any maternal SNPs that in isolation appeared to be associated with SPTB. Interestingly, when we compared our top SNPs with those from the MFMU and SCRN validation cohort there was little overlap in specific SNPs or gene involvement, although mechanisms and pathways demonstrated some degree of concurrence. Similarly, although two neonatal SNPs reached the genome-wide significance level, they did replicate in our validation cohort. The lack of overlap between the cohorts in terms of significant findings reaffirms the complexity and heterogeneity of the syndrome of preterm birth and further emphasizes the need for future investigations of gene-gene, gene-environment, and maternal-fetal interactions. The size of our study allows us to conclude that common genetic variants with large effect sizes, OR of 2 or more, are unlikely to contribute to the mechanism of spontaneous preterm birth. Clear involvement of genetic factors in the mechanism of preterm birth suggests that the mechanism comprises common variants with low effect sizes or rare variants. Moreover, our findings reiterate the long-held belief that there is not one specific genetic etiology that can be identified and targeted as a cause of SPTB.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Genomic and Proteomic Network for Preterm Birth Research (U01-HD-050062; U01-HD-050078; U01-HD-050080; U01-HD-050088; U01-HD-050094).

We are indebted to our medical and nursing colleagues and the infants and their parents who agreed to take part in this study. The following investigators, in addition to those listed as authors, participated in this study:

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development – Stephanie Wilson Archer, MA.; University of Alabama at Birmingham Health System (U01 HD50094, UL1 RR25777) – Rachel L. Copper, MSN CRNP; Pamela B. Files, MSN CRNP; Stacy L. Harris, BSN RN.; University of Pennsylvania (U01 HD5088) – Ian Blair, PhD; Rita Leite, MD.; University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston (U01 HD50078) – Margaret L. Zimmerle, BSN; Janet L. Brandon, RN MSN; Sonia Jordan, RN BSN; Angela Jones, RN BSN.; University of Utah Medical Center, Intermountain Medical Center, LDS Hospital, McKay-Dee Hospital, and Utah Valley Regional Medical Center (U01 HD50080) – Kelly Vorwaller, RN BSN; Sharon Quinn, RN; Valerie S. Morby, RN CCRP; Kathleen N. Jolley, RN BSN; Julie A. Postma, RN BSN CCRP.; Yale University (U01 HD50062) – Kei-Hoi Cheung, PhD; Donna DelBasso; Xiaobo Guo, PhD; Buqu Hu, MS; Hao Huang, MD MPH; Lina Jin, PhD; Analisa L. Lin, MPH; Charles C. Lu, MS; Laura Ment, M.D., Lauren Perley, MA; Laura Jeanne Simone, BA; Feifei Xiao, PhD; Yaji Xu, PhD.; Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Women & Infants Hospital of Rhode Island – Dwight J. Rouse, MD MSPH; Donna Allard, RNC.; Columbia University Hospital, Drexel University, Christiana Care Health Systems, and St. Peter’s University Hospital – Ronald Wapner, MD; Michelle Divito, RN MSN; Sabine Bousleiman, RN MSN MsPH; Vilmarie Carmona, MA; Rosely Alcon, RN BSN; Katty Saravia, MA; Luiza Kalemi, MA; Mary Talucci, RN MSN; Lauren Plante, MD MPH; Zandra Reid, RN BSN; Cheryl Tocci, RN BSN; Marge Sherwood; Matthew Hoffman, MD; Stephanie Lynch, RN; Angela Bayless, RN; Jenny Benson, RN; Jennifer Mann, RN; Tina Grossman, RN; Stephanie Lort, RN; Ashley Vanneman; Elisha Lockhart; Carrie Kitto; Edwin Guzman, MD; Marian Lake, RN; Shoan Davis; Michele Falk; Clara Perez, RN.; Northwestern University – Alan M Peaceman MD, Lara Stein RN, Katura Arego, Mercedes Ramos-Brinson B.S., Gail Mallett RN BSN.; University of North Carolina – John M. Thorp, Jr, MD MPH; Karen Dorman, RN MS; Seth Brody, MD MPH.; University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston and Lyndon Baines Johnson General Hospital/Harris County Hospital District – Sean C. Blackwell, MD; Maria Hutchinson, MPH.

GPN Advisory Board – Anthony Gregg (chair), MD, University of South Carolina School of Medicine; Reverend Phillip Cato, PhD; Traci Clemons, PhD, The EMMES Corporation; Alessandro Ghidini, MD, Inova Alexandria Hospital; Emmet Hirsch, MD, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University; Jeff Murray, MD, University of Iowa; Emanuel Petricoin, PhD, George Mason University; Caroline Signore, MD MPH, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; Charles F. Sing, PhD, University of Michigan; Xiaobin Wang, MD, Children Memorial Hospital.

In addition, the NICHD Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network and the Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network provided specimen samples for the validation analysis.

Footnotes

Data collected at participating sites of the GPN were transmitted to Yale University, the data coordinating center (DCC) for the network, which stored, managed and analyzed the data for this study. On behalf of the GPN, Drs. Heping Zhang (DCC Principal Investigator) and Yaji Xu (DCC Statistician) had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Andrews, Baldwin, Biggio, Bukowski, Ilekis, Parry, Reddy, Song, Varner, Xu, and Zhang declare no conflicts of interest for conducting or interpreting the work described.

References

- Carey JC, Klebanoff MA, Hauth JC, Hillier SL, Thom EA, Ernest JM, Heine RP, Nugent RP, Fischer ML, Leveno KJ, et al. Metronidazole to prevent preterm delivery in pregnant women with asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Network of Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;342:534–540. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002243420802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crider KS, Whitehead N, Buus RM. Genetic variation associated with preterm birth: a HuGE review. Genetics in Medicine: Official Journal of the American College of Medical Genetics. 2005;7:593–604. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000187223.69947.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giarratano G. Genetic influences on preterm birth. MCN. The American journal of maternal child nursing. 2006;31:169–175. doi: 10.1097/00005721-200605000-00008. quiz 176–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X, Liu Z, Wang X, Zhang H. Genetic association test for multiple traits at gene level. Genet Epidemiol. 2013;37:122–9. doi: 10.1002/gepi.21688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hack M, Fanaroff AA. Outcomes of extremely immature infants--a perinatal dilemma. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1993;329:1649–1650. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199311253292210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Ventura SJ. Births: preliminary data for 2012. National Vital Statistics Reports: From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. 2013;62:1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao K, Wang X, Niu T, Xu X, Li A, Chang W, Wang L, Li G, Laird N, Xu X. A candidate gene association study on preterm delivery: application of high-throughput genotyping technology and advanced statistical methods. Human Molecular Genetics. 2004;13:683–691. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine, Committee on Understanding Premature Birth and Assuring Healthy Outcomes. Preterm Birth: Causes, Consequences, and Prevention. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer MS, Demissie K, Yang H, Platt RW, Sauvé R, Liston R. The contribution of mild and moderate preterm birth to infant mortality. Fetal and Infant Health Study Group of the Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System. JAMA. 2000;284:843–849. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.7.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manolio TA. Genomewide association studies and assessment of the risk of disease. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363:166–176. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0905980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD, Ventura SJ, Menacker F, Munson ML. Births: final data for 2003. National Vital Statistics Reports: From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. 2005;54:1–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews TJ, Menacker F, MacDorman MF Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Infant mortality statistics from the 2002 period: linked birth/infant death data set. National Vital Statistics Reports: From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. 2004;53:1–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell S. PLINK. Version 1.07. http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/purcell/plink/

- Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MAR, Bender D, Maller J, Sklar P, de Bakker PIW, Daly MJ, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson AC, Sandin S, Cnattingius S, Reilly M, Pawitan Y, Hultman CM, Lichtenstein P. Maternal effects for preterm birth: a genetic epidemiologic study of 630,000 families. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2009;170:1365–1372. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood NS, Marlow N, Costeloe K, Gibson AT, Wilkinson AR. Neurologic and developmental disability after extremely preterm birth. EPICure Study Group. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;343:378–384. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200008103430601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]