Abstract

Background

It is important to select appropriate targeted therapies for subgroups of patients with lung adenocarcinoma who have specific gene alterations.

Methods

This prospective study was a multicenter project conducted in Taiwan for assessment of lung adenocarcinoma genetic tests. Five oncogenic drivers, including EGFR, KRAS, BRAF, HER2 and EML4-ALK fusion mutations, were tested. EGFR, KRAS, BRAF and HER2 mutations were assessed by MALDI-TOF MS (Cohort 1). EML4-ALK translocation was tested by Ventana method in EGFR-wild type patients (Cohort 2).

Results

From August 2011 to November 2013, a total of 1772 patients with lung adenocarcinoma were enrolled. In Cohort 1 analysis, EGFR, KRAS, HER2 and BRAF mutations were identified in 987 (55.7%), 93 (5.2%), 36 (2.0%) and 12 (0.7%) patients, respectively. Most of these mutations were mutually exclusive, except for co-mutations in seven patients (3 with EGFR + KRAS, 3 with EGFR + HER2 and 1 with KRAS + BRAF). In Cohort 2 analysis, 29 of 295 EGFR-wild type patients (9.8%) were positive for EML4-ALK translocation. EGFR mutations were more common in female patients and non-smokers and KRAS mutations were more common in male patients and smokers. Gender and smoking status were not correlated significantly with HER2, BRAF and EML4-ALK mutations. EML4-ALK translocation was more common in patients with younger age.

Conclusion

This was the first study in Taiwan to explore the incidence of five oncogenic drivers in patients with lung adenocarcinoma and the results could be valuable for physicians in consideration of targeted therapy and inclusion of clinical trials.

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide [1], as well as in Taiwan. To improve the survival for advanced lung adenocarcinoma, strategies to target driver gene alterations are important and currently under intensive investigation.

Several molecular alterations are known to be involved in tumorigenesis of lung adenocarcinoma, such as epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS), v-raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B (BRAF), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), and echinoderm microtubule-associated protein-like 4-anaplastic lymphoma kinase (EML4-ALK) fusion mutations. Mutations in these genes are responsible for both the initiation and maintenance of lung adenocarcinoma [2]. By understanding the biological functions of these driver genes, it may be possible to develop specific therapies for lung cancer with known driver gene mutations.

Recently, Kris et al. demonstrated that patients with an oncogenic driver mutation who received the corresponding targeted therapy had a significantly longer survival time than those with a driver mutation who did not receive the targeted therapy and those without a driver mutation [3]. In comparison with chemotherapy, EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI), including gefitinib, erlotinib and afatinib, have provided a better outcome and quality of life for patients with advanced EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and have become one of the standard first line therapies [4–6]. Similar efficacy was observed in EML4-ALK positive lung cancer patients treated with crizotinib and second-generation ALK inhibitors [7,8].

Many drugs are available now and more will be developed for patients with specific driver gene mutations. Therefore, we decided to conduct a prospective study in five medical centers in Taiwan to explore the incidence of driver gene mutations and to define subgroups of patients in whom candidate driver gene alterations are enriched. Analyses of five driver genes, including EGFR, KRAS, BRAF, HER2 and EML4-ALK, were performed in patients with treatment naïve lung adenocarcinoma.

Materials and Methods

Patients

This multicenter prospective observational study was conducted in five medical centers in Taiwan, including Taichung Veterans General Hospital, National Taiwan University Hospital, China Medical University Hospital, Chung Shan University Hospital and Taichung Tzu Chi Hospital. To be eligible for the study, patients were required to have treatment-naïve and pathologically confirmed lung adenocarcinoma and available tumor specimens for genetic analysis. Patients were excluded if they had lung cancer with histology other than adenocarcinoma, including those with carcinoma not otherwise specified (NOS), or other active malignancy. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the participating institutes, including, Institutional Review Board of Taichung Veterans General Hospital (IRB No. C08197), National Taiwan University Hospital Research Ethics Committee (IRB No. 201111039RIC), Institutional Review Board of Chung Shan Medical University Hospital (IRB No. CS12022), China Medical University and Hospital Research Ethics Committee (IRB No. DMR100-IRB-284[CR-2]) and Taichung Tzu Chi Hospital Research Ethics Committee (IRB No. REC102–7). Written informed consents for genetic testing and clinical data records were obtained from all patients.

Identification of driver mutations

Five oncogenic drivers, including EGFR, KRAS, BRAF, HER2 and EML4-ALK, were tested. EGFR, KRAS, BRAF and HER2 mutations were assessed by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) since August 2011. EML4-ALK translocation was tested by Ventana method in patients with EGFR-wild type lung adenocarcinoma from July 2013. All the tests were performed by ISO15189-certified TR6 Pharmacogenomics Lab (PGL), National Research Program for Biopharmaceuticals (NRPB), the National Center of Excellence for Clinical Trial and Research of NTUH.

Tumor specimens were procured for EGFR, KRAS, BRAF and HER2 mutation analyses as previously described [9]. Briefly, DNA was extracted from the tumors using a QIAmp DNA Mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The genetic alterations of EGFR, KRAS, BRAF and HER2 were detected by MALDI-TOF MS based on the methods used in our previous reports with modifications [10,11]. Briefly, we expanded the multiplex gene-testing panel to include EGFR, KRAS, BRAF and HER2 genes. We performed the analysis according to manufacturer’s protocol for MassARRAY system (Sequenom, San Diego, CA). In the biochemical reaction, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) followed by single nucleotide extension was performed by using primers and corresponding detection probes to amplify the region containing each target mutation. After SpectroClean Resin clean up, samples were loaded onto the matrix of SpectroCHIP by Nanodispenser (Matrix) and then analyzed by Bruker Autoflex MALDI-TOF MS. Data were collected and analyzed by Typer 4 software (Sequenom, San Diego, CA). The PCR primers and probes used in the present study were summarized in S1 Table.

Because EGFR mutations and EML4-ALK translocations are almost mutually exclusive [12], assessment of EML4-ALK translocations was only performed in patients with EGFR-wild type lung adenocarcinoma in this project by Ventana method [13]. Briefly, the assay (Ventana IHC, Ventana, Tucson, AZ) was a fully automated IHC assay developed by Ventana, using the pre-diluted Ventana anti-ALK (D5F3) Rabbit monoclonal primary antibody, together with the Optiview DAB IHC detection kit and Optiview Amplification kit on the Benchmark XT stainer. Each specimen was also stained with a matched Rabbit Monoclonal Negative Control Immunoglobulin antibody. The manufacture’s scoring algorithm was a binary scoring system (positive or negative for ALK status), which we adopted for evaluating the staining results. Neoplastic cells labeled with the ALK IHC assay were evaluated for presence or absence of the DAB signal. Presence of strong granular cytoplasmic staining in tumor cells (any percentage of positive tumor cells) was deemed to be ALK positive, while absence of strong granular cytoplasmic staining in tumor cells was deemed to be ALK negative.

Data records and response evaluation

Activating mutation of EGFR gene is the most common genetic alteration in lung adenocarcinoma in East Asians [14]. Therefore, in addition to exploration of the incidence of driver mutations, we also evaluated the efficacy of EGFR-TKI in patients with EGFR-mutant lung adenocarcinoma. Clinical data for analysis included patients’ age, gender, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS), tumor stage and smoking status. TNM (tumor, node, and metastases) staging was done according to the 7th edition of the American Joint Committee for Cancer (AJCC) staging system [15]. Chest computed tomographies (CT), including the liver and adrenal glands, and other required imaging studies for response evaluation were reviewed by two chest physicians. Unidimensional measurements as defined by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1 were used in this study [16].

Statistical methods

Univariate analyses by Fisher’s exact test and Pearson Chi-square test were conducted on the frequency of five oncogenic drivers and on the objective response rate (ORR) and disease control rate (DCR) of EGFR-TKI therapy to evaluate the effects of clinical factors relating to patient and disease characteristics. Multivariate analyses of ORR and DCR were performed using logistic regression model. The Kaplan—Meier method was used to estimate progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS). Differences in survival time were analyzed using the log-rank test. Multivariate analyses of PFS and OS were performed using Cox proportional hazard model. All statistical tests were done with SPSS 15.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Two-tailed tests and p values <0.05 for significance were used.

Results

Patient characteristics

From August 2011 to November 2013, a total of 1772 patients with treatment-naïve lung adenocarcinoma were enrolled as Cohort 1 for EGFR, KRAS, BRAF and HER2 genetic analyses. With the development of Ventana method in July 2013 and the availability of tumor tissues, EML4-ALK translocation testing was performed in total 295 patients with EGFR-wild type lung adenocarcinoma, who were enrolled as Cohort 2. The baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Briefly, in Cohort 1, the median age was 58 years (range 21–100), 821 patients (46.3%) were male, 1179 patients (66.5%) were non-smokers and 1248 patients (70.4%) had advanced stage diseases (stage IIIb or IV). In Cohort 2, the median age was 61 yeas (range 21–100), 150 patients (50.8%) were male, 177 patients (60.0%) were non-smokers and 198 patients (67.1%) had advanced stage diseases.

Table 1. Characteristics and demographic data.

| Characteristics | Cohort 1* | Cohort 2** |

|---|---|---|

| (n = 1772) | (n = 295) | |

| Age (years), median (range) | 58 (21–100) | 61 (21–100) |

| Gender | ||

| Male, n (%) | 821 (46.3) | 150 (50.8) |

| Female, n (%) | 951 (53.7) | 145 (49.2) |

| Smoking status | ||

| Non-smokers, n (%) | 1179 (66.5) | 177 (60.0) |

| Current/former smokers, n (%) | 593 (33.5) | 118 (40.0) |

| Stage, n (%) | ||

| I | 290 (16.4) | 49 (16.6) |

| II | 81 (4.6) | 18 (6.1) |

| IIIa | 141 (8.0) | 29 (9.8) |

| IIIb | 121 (6.8) | 17 (5.8) |

| IV | 1127 (63.6) | 181 (61.4) |

| N/A | 12 (0.6) | 1 (0.3) |

*Cohort 1: lung adenocarcinoma.

**Cohort 2: epidermal growth factor receptor-wild type lung adenocarcinoma.

N/A, not applicable.

Incidence of five oncogenic drivers

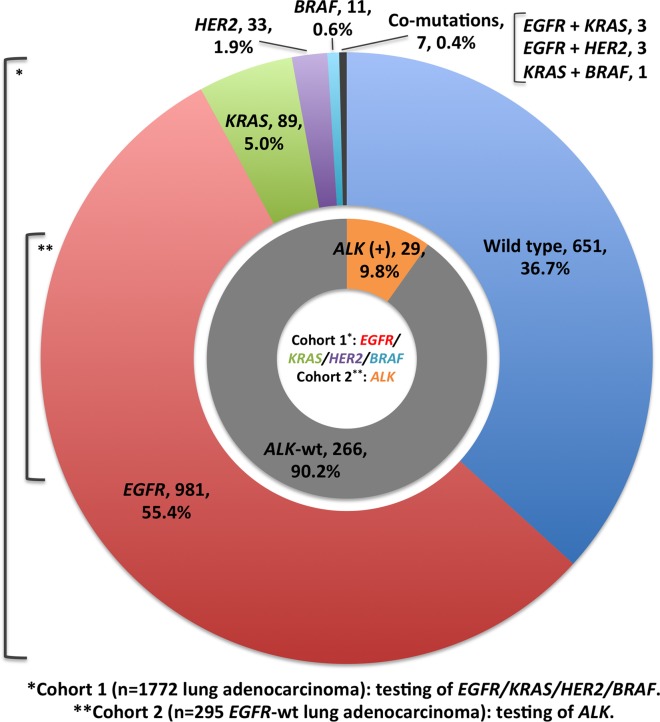

The oncogenic driver mutations detected in the present study are summarized in Table 2. The incidence of five driver gene mutations is shown in Fig. 1 and Table 2. In the Cohort 1 analysis, 987 of 1772 lung adenocarcinoma patients (55.7%) harbored activated EGFR mutations, which accounted for the majority of diver gene mutations. Mutations in KRAS, HER2 and BRAF genes were identified in 93 (5.2%), 36 (2.0%) and 12 (0.7%) patients, respectively. A total of 651 patients (36.7%) had no detectable driver gene mutation. Majority of the genetic alterations were mutually exclusive, except for co-mutations in seven (0.4%) patients (3 with EGFR and KRAS mutations, 3 with EGFR and HER2 mutations and 1 with KRAS and BRAF mutations). In the Cohort 2 analysis, 29 of 295 patients with EGFR-wild type lung adenocarcinoma (9.8%) were found to have EML4-ALK translocation and none of them harbored other driver gene mutations.

Table 2. Characteristics of genetic alterations assessed in the present study.

| Gene* | Exon/Domain | Patient No. | Assessed genetic alterations |

|---|---|---|---|

| EGFR | Exon 18 | 18 | E709A, E709G, E709V |

| G719A, G719C, G719N, G719S | |||

| Exon 19 | 434 | E746-A750del, E746-T751>A, | |

| E746-S752>V, L747-A750>P, L747-T751>P, | |||

| L747-S752del, L747-T751del, L747-P753>S, | |||

| E746-T751>I, E746-T751del, E746-S752>A, | |||

| E746-S752>D, L747-A750>P, L747-T751>Q, | |||

| L747-E749del, L747-P753>Q, L747-T751>S | |||

| Exon 20 | 3 | T790M, S768I | |

| Exon 21 | 483 | L858R, L858Q, L861Q | |

| Exon 18–21 | 49 | Complex mutations | |

| KRAS | Codon 12 | 89 | G12S, G12R, G12C, G12D, G12A, G12V |

| Codon 13 | 4 | G13S, G13C, G13R, G13D, G13V, G13A | |

| HER2 | Exon 20 | 36 | A775-G776insYVMA |

| BRAF | Exon 15 | 12 | V600E |

| ALK | N/A | 29 | EML4-ALK translocation |

EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase; EML4, echinoderm microtubule-associated protein like 4.

*Cohort 1 (1772 patients with lung adenocarcinoma) testing of EGFR, KRAS, HER2 and BRAF mutations and cohort 2 (295 patients with EGFR-wild type lung adenocarcinoma) testing of EML4-ALK translocation.

Fig 1. Spectrum of genetic alterations among patients with lung adenocarcinoma.

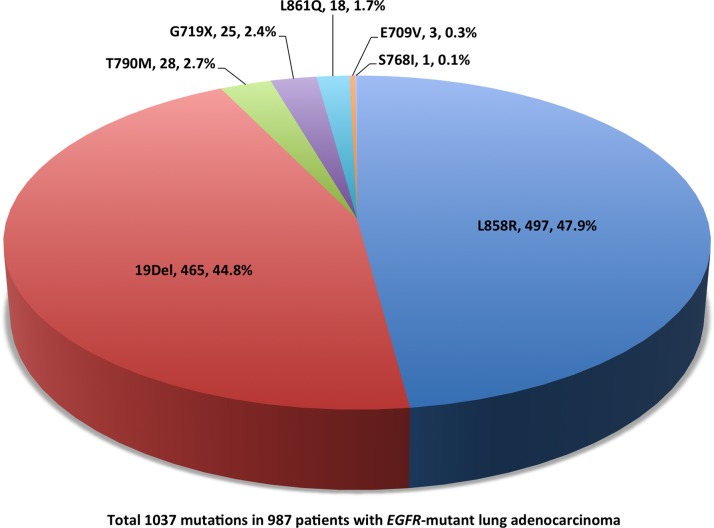

The detail of EGFR mutations is depicted in Fig. 2. A total of 1037 EGFR mutations were detected in 987 patients, including 49 patients (5.0%) who harbored complex mutations. Exon 19 in-frame deletions (44.8%) and exon 21 L858R (47.9%) were the major types of EGFR mutations. Furthermore, a total of 28 patients had primary exon 20 T790M mutation in the treatment-naïve tumor samples, mainly as part of complex mutations.

Fig 2. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation spectrum among patients with EGFR-mutant lung adenocarcinoma (complex mutations are counted as separated mutation types here).

Association between patient characteristics and driver gene mutations

The analysis of association between patient characteristics and driver gene mutations is shown in Table 3. For EGFR mutations, a significantly higher mutation rate was noted in female then in male patients (65.2 vs. 44.7%, P < 0.001) and in non-smokers then in smokers (63.9 vs. 39.5%, P < 0.001). Neither age nor tumor stage was significantly correlated with EGFR mutation.

Table 3. Univariate analysis of genetic alterations and clinical characteristics.

| EGFR * | KRAS * | HER2 * | BRAF * | ALK ** | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | n (%) | P value | n (%) | P value | n (%) | P value | n (%) | P value | n (%) | P value |

| Age (years) | 0.501 | 0.200 | 0.502 | 0.777 | 0.002 | |||||

| ≤ 65 | 536 (55.0) | 45 (4.6) | 22 (2.3) | 6 (0.6) | 25 (14.0) | |||||

| > 65 | 451 (56.6) | 48 (6.0) | 14 (1.8) | 6 (0.8) | 4 (3.4) | |||||

| Gender | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.312 | 0.781 | 0.331 | |||||

| Male | 367 (44.7) | 76 (9.3) | 20 (2.4) | 5 (0.6) | 12 (8.0) | |||||

| Female | 620 (65.2) | 17 (1.8) | 16 (1.7) | 7 (0.7) | 17 (11.7) | |||||

| Smoking status | <0.001 | <0.001 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.167 | |||||

| Non-smokers | 753 (63.9) | 20 (1.7) | 24 (2.0) | 8 (0.7) | 21 (11.9) | |||||

| Current/former smokers | 234 (39.5) | 73 (12.3) | 12 (2.0) | 4 (0.7) | 8 (6.8) | |||||

| Stage, n (%) # | 0.187 | 1.000 | 0.015 | 0.754 | 0.837 | |||||

| I-IIIa | 298 (58.2) | 27 (5.3) | 4 (0.8) | 4 (0.9) | 10 (10.4) | |||||

| IIIb-IV | 682 (54.6) | 66 (5.3) | 32 (2.6) | 8 (0.6) | 19 (9.6) | |||||

EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase.

*Cohort 1 (1772 patients with lung adenocarcinoma) testing of EGFR, KRAS, HER2 and BRAF mutations.

**Cohort 2 (295 patients with EGFR-wild type lung adenocarcinoma) testing of EML4-ALK translocation.

#Exclude 12 patients of cohort 1 and 1 patients of cohort 2 with incomplete data on tumor staging For KRAS mutations, a significantly higher mutation rate was noted in male then in female patients (9.3 vs. 1.8%, P < 0.001) and in smokers then in non-smokers (12.3 vs. 1.7%, P < 0.001). Neither age nor tumor stage were correlated with KRAS mutation. For HER2 mutations, patients with more advanced diseases were associated with a higher mutation rate (2.6% in stage IIIb-IV vs. 0.8% in stage I-IIIa, P = 0.015). For BRAF mutation, there was no significant association between patient characteristics and the mutation rate.

In the Cohort 2 analysis, age was the only factor that correlated significantly with EML4-ALK translocation and patients with younger age (≤ 65 years) had a higher mutation rate than patients aged more than 65 years (14.0 vs. 3.4%, P = 0.002). Moreover, we observed a trend toward a higher mutation rate in non-smokers compared with smokers (11.9 vs. 6.8%) but the trend did not reach a level of significance (P = 0.167). Neither age nor tumor stage was correlated significantly with EML4-ALK translocation.

Efficacy of EGFR-TKI in EGFR-mutant lung adenocarcinoma

In total, 352 patients who had EGFR-mutations and lesions that could be measured for treatment responses received EGFR-TKI therapy as the first line treatment (336 with gefitinib and 16 with erlotinib). The drug prescribed was chosen by the physicians in charge. Three patients achieved complete response, 203 patients achieved partial response, 95 patients had stable disease and 51 patients had progressive disease. The ORR and DCR were 58.5% and 85.5%, respectively. Univariate analyses of ORR and DCR are shown in Table 4. Patients with exon 19 deletions were associated with a higher ORR than those with L858R and other uncommon mutations (68.2 vs. 51.2 vs. 48.0%, P = 0.004). No other factors correlated significantly with ORR. In DCR analysis, females, non-smokers, patients with better ECOG PS (0–1) and those with exon 19 deletions were associated with a significantly higher DCR (P = 0.001, 0.013, <0.001 and 0.004, respectively). In multivariate logistic regression model, the exon 19 deletion was the only factor that predicted both a higher ORR (odds ratio 2.04, 95% CI 1.31–3.17, P = 0.002) and a higher DCR (odds ratio 2.40, 95% CI 1.21–4.77, P = 0.012). Gender and ECOG PS (0–1) remained significantly correlated with DCR in multivariate analysis (data not shown).

Table 4. Univariate analysis of objective response rate and disease control rate in patients harboring EGFR mutations (n = 352).

| Patient No. | ORR (%) | P value* | DCR (%) | P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 0.449 | 0.880 | |||

| ≤ 65 | 189 | 56.6 | 85.2 | ||

| > 65 | 163 | 60.7 | 85.9 | ||

| Gender | 0.147 | 0.001 | |||

| Male | 131 | 53.4 | 77.1 | ||

| Female | 221 | 61.5 | 90.5 | ||

| Smoking | 0.208 | 0.013 | |||

| Non-smokers | 266 | 60.5 | 88.3 | ||

| Current/former smokers | 86 | 52.3 | 76.7 | ||

| ECOG PS # | 0.660 | <0.001 | |||

| 0–1 | 289 | 58.5 | 88.6 | ||

| ≥ 2 | 57 | 54.4 | 68.4 | ||

| Stage | 0.564 | 0.393 | |||

| IIIb | 12 | 50.0 | 75.0 | ||

| IV | 340 | 58.8 | 85.9 | ||

| Mutation types | 0.004 | 0.004 | |||

| Exon 19 deletions | 157 | 68.2 | 91.1 | ||

| Exon 21 L858R | 170 | 51.2 | 82.9 | ||

| Others | 25 | 48.0 | 68.0 | ||

| EGFR-TKIs | 0.448 | 0.142 | |||

| Gefitinib | 336 | 58.0 | 84.8 | ||

| Erlotinib | 16 | 68.8 | 100 |

EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; ORR, objective response rate; DCR, disease control rate; ECOG PS, ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status.

*Mutation types by Pearson Chi-square test; otherwise by Fisher’s exact test.

#Exclude 6 cases with missing ECOG PS data.

The median PFS and OS were 11.6 (95% CI 10.0–13.2) and 39.4 (95% CI not applicable) months, respectively. In the univariate analysis, non-smokers and patients with ECOG PS 0–1 were associated with a significant longer PFS and ECOG PS (0–1) was the only factor that predicted a longer OS significantly (data not shown). Although patients harbored exon 19 deletions were associated with both a higher ORR and DCR, neither PFS (HR 0.74, 95% CI 0.55–1.00, P = 0.053) nor OS (HR 0.70, 95% CI 0.42–1.16, P = 0.163) was significantly correlated with EGFR mutation types in multivariate analysis. In multivariate Cox proportional hazard model, ECOG PS (0–1) was the only factor that independently predicted both a longer PFS (HR 0.67, 95% CI 0.46–0.97, P = 0.034) and OS (HR 0.46, 95% CI 0.27–0.79, P = 0.005).

Discussion

The success of EGFR and ALK inhibitor therapies in lung cancer patients with EGFR mutations and EML4-ALK translocations initiated the era of targeted therapy in advanced NSCLC [5,8] and shifted treatment from platinum-based chemotherapy to molecularly targeted therapy. Recent genomic studies in lung adenocarcinoma have identified other potential therapeutic targets, such as mutations in KRAS, HER2 and BRAF, ROS1 rearrangements, RET fusions and MET amplification [17,18]. As the current trend of NSCLC treatment, especially lung adenocarcinoma, has been shifted from tumor stage-based to more individualized therapies based on histological and molecular characteristics [19], the increasing importance of genomic information should prompt physicians to obtain adequate tissue specimens when planning diagnostic procedures [20].

In East Asia, there are several unique characteristics of lung cancer [21], including the predominance of adenocarcinoma over other cell types and a large proportion of never smoker and female patients. Such features may provide keys to further investigate the treatment or prevention of lung cancer in East Asians. Moreover, the incidences of activating mutations of oncogenic drivers in Western and Asian populations are different, especially the EGFR and KRAS mutations [3,18,22,23]. In the present study, we showed that the incidence of EGFR mutations in Taiwanese lung adenocarcinoma patients was 55.7%, which was similar to the results of PIONEER study [14]. EGFR mutation is the most important biomarker for predicting the outcome of EGFR-TKI therapy. In the present study, the ORR of EGFR-TKI therapy was 58.5%, which was slightly lower than that of randomized controlled trials. However, we also enrolled patients with poor ECOG PS (2 or more) and outcome with regard to DCR, PFS and OS was similar to previous studies [4,5]. The incidence of KRAS mutation in the present study was only 5.0%, much lower than that reported in Caucasians and even lower than that in other Asian countries [18,22]. Since there is a significant association between KRAS mutations and smoking behaviors [22,24], the relatively high rate of non-smoking lung cancers in Taiwan might be one reason for the lower KRAS mutation rate in the present study. Herein, our results disclosed the higher EGFR mutation rate in female and non-smokers and higher KRAS mutation rate in male and smokers, which were in line with the results of previous studies [24,25].

KRAS mutations in lung adenocarcinoma consist of single amino acid substitutions in hotspots located mostly in codon 12 and rarely in codons 13 and 61 [26,27]. In our study, codon 12 and codon 13 mutations were detected, with much higher mutation rate in codon 12 than in codon 13 (95.7% vs. 4.3%). There is evidence that different KRAS mutant proteins have differing clinical significance. In previous study, either G12C or G12V-mutant KRAS predicted shorter progression free survival to EGFR-TKI compared to wild type or other KRAS mutations [28]. Despite the lack of effective KRAS-targeted agents currently, detection of KRAS mutations could be considered to apply in clinical practice for its prognostic value [29,30].

The rate of BRAF V600E mutation was 0.7% (12/1772) in the present study with eight non-smokers and four smokers. In the study by An et al., BRAF mutation rate was 2.3% (7/307) in lung adenocarcinoma, while BRAF exon 15 mutation rate was 0.98% (3/307) [31]. The BRAF V600E mutation rate was similar to that in our study. Our results showed that there was no significant association of BRAF V600E mutation with patients’ age, gender, smoking status or tumor stage. This differs from a recent meta-analysis by Chen et al. [32], showing that BRAF V600E mutation was significantly correlated with female gender and non-smoking history. Because different cohorts of patients and detection methods potentially confound the screening of uncommon mutations, further studies are needed to clarify the nature of BRAF mutations. Although BRAF mutations are uncommon, they represent an important therapeutic target due to the availability of individualized therapies in clinical use for melanoma and the promising results reported in ongoing clinical trials for NSCLC patients [33].

HER2 mutations consist of in-frame insertions in exon 20, especially HER2YVMA mutant, leading to constitutive activation of the receptor and downstream AKT and MEK pathways [34]. HER2 mutations meet the definition of genetic driver and the concept of transforming property of such a genetic alteration has been proved in preclinical models [35]. In the study by Mazieres et al., HER2 mutation was identified in 65 (1.7%) of 3800 patients tested with a high proportion of women (69%) and never-smokers (52.3%) [36]. In our study, similar HER2 mutation rate (2.0%) was found with a higher mutation rate in patients with advanced stage diseases. As several agents might be active in HER2-mutant lung adenocarcinoma, it is important to screen for HER2 mutations for the potential efficacy of HER2-targeted medications.

ALK rearrangement has been demonstrated to be a potent oncogenic driver and a promising therapeutic target in NSCLC. The rate of ALK rearrangements ranged from 3 to 7% of unselected patients with NSCLC [37–39]. Similar to EGFR mutations, ALK rearrangements are associated with distinct clinical features, including younger age at diagnosis, never of light smokers and adenocarcinoma histology. Phase 3 study of crizotinib in previously treated patients with ALK-rearranged advanced NSCLC showed an ORR of 65% and a PFS of 7.7 months, which was significantly superior to the results with standard chemotherapy [8].

FISH analysis is the only approved diagnostic test to detect break-apart signals in ALK rearrangement. However, the apparatuses required for FISH analysis may not be available in all diagnostic laboratories. IHC can be an alternative to FISH and using the highly sensitive detection methods in combination with high affinity antibodies, IHC can effectively detect ALK fusion protein in lung adenocarcinoma with high sensitivity and specificity [40,41]. Automated IHC assay system devised by Ventana was used in this study. Ying et al. assessed 196 lung adenocarcinomas using Ventana IHC, FISH, Cell Signaling Technology (CST) IHC and RT—PCR and the results showed that 65 (33%), 63 (32%), 70 (36%) and 69 (35%) cases were ALK positive, respectively [13]. The sensitivity and specificity of Ventana IHC were 100% and 98%. The automated Ventana IHC system is desirable to be considered as a guide to prescribe ALK inhibitors treatment, as IHC is a routine methodology in most pathology laboratories to detect a protein of interest. In the case of the availability of tumor tissues, our results may be slightly skewed due to the small sample size tested for ALK rearrangements.

In the present study, around 35% of lung adenocarcinoma patients did not have detectable oncogenic drivers. The comprehensive molecular profiling of 230 resected lung adenocarcinomas reported recently by Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network also showed that 24.4% of patients had no detectable driver oncogenic mutations at initial identification of candidate driver genes [17].

In summary, our study demonstrates that lung adenocarcinoma defined by specific driver gene alterations could be considered as different diseases. The identification of driver mutations has heralded a new era of targeted therapy in lung adenocarcinoma with currently available and potentially targetable genetic aberrations.

Supporting Information

(PDF)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Comprehensive Cancer Center of Taichung Veterans General Hospital for the assistance in data collection and management and Pharmacogenometics Lab of National Research Program for Biopharmaceuticals for technical service support.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1. Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64: 9–29. 10.3322/caac.21208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bronte G, Rizzo S, La Paglia L, Adamo V, Siragusa S, Ficorella C, et al. Driver mutations and differential sensitivity to targeted therapies: a new approach to the treatment of lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Treat Rev. 2010;36 Suppl 3: S21–29. 10.1016/S0305-7372(10)70016-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kris MG, Johnson BE, Berry LD, Kwiatkowski DJ, Iafrate AJ, Wistuba II, et al. Using multiplexed assays of oncogenic drivers in lung cancers to select targeted drugs. JAMA. 2014;311: 1998–2006. 10.1001/jama.2014.3741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lee CK, Brown C, Gralla RJ, Hirsh V, Thongprasert S, Tasi CM, et al. Impact of EGFR inhibitor in non-small cell lung cancer on progression-free and overall survival: a meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105: 595–605. 10.1093/jnci/djt072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, Yang CH, Chu DT, Saijo N, et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2009;361: 947–957. 10.1056/NEJMoa0810699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Thongprasert S, Duffield E, Saijo N, Wu YL, Yang JC, Chu DT, et al. Health-related quality-of-life in a randomized phase III first-line study of gefitinib versus carboplatin/paclitaxel in clinically selected patients from Asia with advanced NSCLC (IPASS). J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6: 1872–1880. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31822adaf7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shaw AT, Kim DW, Mehra R, Tan DS, Felip E, Chow LQ, et al. Ceritinib in ALK-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;370: 1189–1197. 10.1056/NEJMoa1311107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shaw AT, Kim DW, Nakagawa K, Seto T, Crino L, Ahn MJ, et al. Crizotinib versus chemotherapy in advanced ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368: 2385–2394. 10.1056/NEJMoa1214886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tseng JS, Wang CL, Huang MS, Chen CY, Chang CY, Yang TY, et al. Impact of EGFR Mutation Detection Methods on the Efficacy of Erlotinib in Patients with Advanced EGFR-Wild Type Lung Adenocarcinoma. PLoS One. 2014;9: e107160 10.1371/journal.pone.0107160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Su KY, Chen HY, Li KC, Kuo ML, Yang JC, Chan WK, et al. Pretreatment epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) T790M mutation predicts shorter EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor response duration in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30: 433–440. 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.3224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tsai TH, Su KY, Wu SG, Chang YL, Luo SC, Jan IS, et al. RNA is favourable for analysing EGFR mutations in malignant pleural effusion of lung cancer. Eur Respir J. 2012;39: 677–684. 10.1183/09031936.00043511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sasaki T, Rodig SJ, Chirieac LR, Janne PA. The biology and treatment of EML4-ALK non-small cell lung cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46: 1773–1780. 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ying J, Guo L, Qiu T, Shan L, Ling Y, Liu X, et al. Diagnostic value of a novel fully automated immunochemistry assay for detection of ALK rearrangement in primary lung adenocarcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2013;24: 2589–2593. 10.1093/annonc/mdt295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shi Y, Au JS, Thongprasert S, Srinivasan S, Tsai CM, Khoa MT, et al. A prospective, molecular epidemiology study of EGFR mutations in Asian patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer of adenocarcinoma histology (PIONEER). J Thorac Oncol. 2014;9: 154–162. 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Handbook. 7th ed New York: Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45: 228–247. 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;511: 543–550. 10.1038/nature13385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Seo JS, Ju YS, Lee WC, Shin JY, Lee JK, Bleazard T, et al. The transcriptional landscape and mutational profile of lung adenocarcinoma. Genome Res. 2012;22: 2109–2119. 10.1101/gr.145144.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. West H, Harpole D, Travis W. Histologic considerations for individualized systemic therapy approaches for the management of non-small cell lung cancer. Chest. 2009;136: 1112–1118. 10.1378/chest.08-2484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cardarella S, Johnson BE. The impact of genomic changes on treatment of lung cancer. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188: 770–775. 10.1164/rccm.201305-0843PP [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bell DW, Brannigan BW, Matsuo K, Finkelstein DM, Sordella R, Settleman J, et al. Increased prevalence of EGFR-mutant lung cancer in women and in East Asian populations: analysis of estrogen-related polymorphisms. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14: 4079–4084. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Serizawa M, Koh Y, Kenmotsu H, Isaka M, Murakami H, Akamatsu H, et al. Assessment of mutational profile of Japanese lung adenocarcinoma patients by multitarget assays: a prospective, single-institute study. Cancer. 2014;120: 1471–1481. 10.1002/cncr.28604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Barlesi F, Blons H, Beau-Faller M, Rouquette I, Quafik L, Mosser J, et al. Biomarkers (BM) France: Results of routine EGFR, HER2, KRAS, BRAF, PI3KCA mutations detection and EML4-ALK gene fusion assessment on the first 10,000 non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients (pts). J Clin Oncol. 2013;31: (suppl; abstr 8000). [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tam IY, Chung LP, Suen WS, Wang E, Wong MC, Ho KK, et al. Distinct epidermal growth factor receptor and KRAS mutation patterns in non-small cell lung cancer patients with different tobacco exposure and clinicopathologic features. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12: 1647–1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ding L, Getz G, Wheeler DA, Mardis ER, McLellan MD, Cibulskis K, et al. Somatic mutations affect key pathways in lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2008;455: 1069–1075. 10.1038/nature07423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Downward J. Targeting RAS signalling pathways in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3: 11–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rodenhuis S, Slebos RJ. Clinical significance of ras oncogene activation in human lung cancer. Cancer Res. 1992;52: 2665s–2669s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ihle NT, Byers LA, Kim ES, Saintigny P, Lee JJ, Blumenschein GR, et al. Effect of KRAS oncogene substitutions on protein behavior: implications for signaling and clinical outcome. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104: 228–239. 10.1093/jnci/djr523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Izar B, Zhou H, Heist RS, Azzoli CG, Muzikansky A, Scribner EE, et al. The prognostic impact of KRAS, its codon and amino acid specific mutations, on survival in resected stage I lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2014;9: 1363–1369. 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sun JM, Hwang DW, Ahn JS, Ahn MJ, Park K. Prognostic and predictive value of KRAS mutations in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. PLoS One. 2013;8: e64816 10.1371/journal.pone.0064816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. An SJ, Chen ZH, Su J, Zhang XC, Zhong WZ, Yang JJ, et al. Identification of enriched driver gene alterations in subgroups of non-small cell lung cancer patients based on histology and smoking status. PLoS One. 2012;7: e40109 10.1371/journal.pone.0040109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chen D, Zhang LQ, Huang JF, Liu K, Chuai ZR, Yang Z, et al. BRAF mutations in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9: e101354 10.1371/journal.pone.0101354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Planchard D, Kim TM, Mazieres J, Quoix E, Riely GJ, Barlesi F, et al. Dabrafenib in patients with BRAF V600E-mutant advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): A multicenter, open-label, phase II trial (BRF113928). Ann Oncol. 2014;25: 1–41. 10.1093/annonc/mdu438 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Perera SA, Li D, Shimamura T, Raso MG, Ji H, Chen L, et al. HER2YVMA drives rapid development of adenosquamous lung tumors in mice that are sensitive to BIBW2992 and rapamycin combination therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106: 474–479. 10.1073/pnas.0808930106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shimamura T, Ji H, Minami Y, Thomas RK, Lowell AM, Shan K, et al. Non-small-cell lung cancer and Ba/F3 transformed cells harboring the ERBB2 G776insV_G/C mutation are sensitive to the dual-specific epidermal growth factor receptor and ERBB2 inhibitor HKI-272. Cancer Res. 2006;66: 6487–6491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mazieres J, Peters S, Lepage B, Cortot AB, Barlesi F, Beau-Faller M, et al. Lung cancer that harbors an HER2 mutation: epidemiologic characteristics and therapeutic perspectives. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31: 1997–2003. 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.6095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Koivunen JP, Mermel C, Zejnullahu K, Murphy C, Lifshits E, Holmes AJ, et al. EML4-ALK fusion gene and efficacy of an ALK kinase inhibitor in lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14: 4275–4283. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kwak EL, Bang YJ, Camidge DR, Shaw AT, Solomon B, Maki RG, et al. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibition in non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363: 1693–1703. 10.1056/NEJMoa1006448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Soda M, Choi YL, Enomoto M, Takada S, Yamashita Y, Ishikawa S, et al. Identification of the transforming EML4-ALK fusion gene in non-small-cell lung cancer. Nature. 2007;448: 561–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mino-Kenudson M, Chirieac LR, Law K, Hornick JL, Lindeman N, Mark EJ, et al. A novel, highly sensitive antibody allows for the routine detection of ALK-rearranged lung adenocarcinomas by standard immunohistochemistry. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16: 1561–1571. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Murakami Y, Mitsudomi T, Yatabe Y. A Screening Method for the ALK Fusion Gene in NSCLC. Front Oncol. 2012;2: 24 10.3389/fonc.2012.00024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.