Abstract

Over the past years, a growing number of studies have indicated that patients suffering from inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) have an increased risk of developing cardiovascular disease. Both are chronic inflammatory diseases and share certain pathophysiological mechanisms that may influence each other. High levels of cytokines, C-reactive protein (CRP), and homocysteine in IBD patients may lead to endothelial dysfunction, an early sign of atherosclerosis. IBD patients, in general, do not show the typical risk factors for cardiovascular disease but changes in lipid profiles similar to the ones seen in cardiovascular events have been reported recently. Higher levels of coagulation factors frequently occur in IBD which may predispose to arterial thromboembolic events. Finally, the gut itself may have an impact on atherogenesis during IBD through its microbiota. Microbial products are released from the inflamed mucosa into the circulation through a leaky barrier. The induced rise in proinflammatory cytokines could contribute to endothelial damage, artherosclerosis and cardiovascular events. Although large retrospective studies favor a link between IBD and cardiovascular diseases the mechanisms behind still remain to be determined.

Keywords: Crohn’s disease, Ulcerative colitis, cardiovascular diseases, coronary artery disease, thromboembolism, endotoxins, LPS, dyslipidemia

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs), i.e. Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), are chronic inflammatory diseases of the intestines that bear many venous vascular comorbidities, e.g. deep venous thrombosis or portal vein thrombosis. While the risk of developing venous disease in IBD is well established [1] the question whether IBD patients are also at risk of developing ischemic vascular diseases still remains elusive. A recent meta-review suggested that patients with IBD may indeed be at an increased risk of ischemic vascular diseases [2]. Studies have shown that chronic systemic inflammation can lead to endothelial dysfunction and platelet aggregation, precursors in the development of atherosclerosis and coronary artery disease (CAD) [3]. The weight of the evidence, mechanistically, biologically, and epidemiologically, support the notion that systemic inflammation, either induced experimentally or from what has been observed in chronic inflammatory diseases like rheumatoid arthritis or chronic kidney disease, is associated with a heightened state of cardiovascular risk. High levels of circulating cytokines and C-reactive protein (CRP) are characteristic of IBD and it is therefore expected that they contribute to endothelial dysfunction and atherogenesis. During the dangerous situation of plaque rupture when the thrombogenic core of the plaque is exposed to the blood stream, thrombus formation may occur and cause acute coronary syndrome, a risk for IBD patients who are known to have a deregulated coagulation system [4]. The intestinal microbiom could play an important role in promoting arterial disease. IBD patients have a disrupted mucosal barrier and therefore bacterial products that have translocated through the gut lining may enter the circulation and directly promote inflammation by activating immune cells and endothelial cells, known triggers in the onset or progression of cardiovascular disease. This review will highlight some likely factors and mechanisms that underlie the increased risk of cardiovascular disease in IBD patients.

Clinical studies pro and contra linking IBD with CAD

The occurrence of venous thrombotic events in IBD has been extensively investigated and described in numerous studies [5-8]. All in all, the data indicate that patients with IBD have a 1.7-5.9 fold higher risk of developing venous thromboembolism, such as deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary emboli, portal vein thrombosis and cerebral venous sinus thrombosis [1]. It has been also suggested that venous thromboembolism was pathogenetically more specific to IBD than chronic inflammation itself because chronic inflammatory diseases like rheumatoid arthritis or coeliac disease neither had an increased risk of thromboembolism [9]. For a comprehensive review on IBD and venous disease the reader is referred to Tan et al. [1].

The connection between IBD and arterial thromboembolic events has not yet been clarified but the majority of the larger studies point to a modest increase in a risk for IBD patients to develop CAD. Almost all of these studies are retrospective and heterogeneous in their methodology and subjects were mostly drawn from insurance registers and national patient databases. The results of these studies are briefly summarized here.

Observations that support an association of IBD with cardiovascular diseases

CAD and myocardial infarction

First evidence that IBD may be associated with CAD came from a study by Bernstein et al. who reported an increased risk of CAD in males and females with CD and UC (1.26 incidence rate ratio [IRR]; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.11-1.44) [10]. Later, in a longitudinal cohort study by Yarur et al., in which patients were followed over 50 months, an increased hazard ratio (HR) (2.85 HR unadjusted; 95 % CI,1.82-4.46) for developing CAD was found in IBD patients [11]. Interestingly, the IBD patients in this study had significantly lower rates of traditional risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and obesity but a higher number of white blood cells, a non-traditional risk factor for CAD (1.23 HR; 95 % CI, 1.15-1.33) [11]. Using 2,831 IBD patients recruited from the Finnish National Health insurance register, a different group also reported that CAD was more frequent in IBD patients than in control subjects (p=0.004), especially in women [12]. In a nationwide Danish cohort study, Rungoe et al. observed an increased risk of CAD within the first year after diagnosis with IBD (2.13 IRR; 95% CI, 1.91 to 2.38) [13]. The authors noticed that the risk of CAD was lower among IBD patients that were on 5-ASA treatment (1.16 IRR; 95% CI, 1.06-1.26) as compared to non-users (1.36 IRR; 95% CI, 1.22-1.51). A good indication that IBD may be a risk factor for developing CAD comes from a meta-analysis that pooled maximally adjusted odd ratios (OR) and demonstrated that IBD was associated with an 18% increased risk of CAD (1.18 OR adjusted, 95% CI, 1.08-1.31) [2]. The risk increase was observed in both CD and UC and seemed to be gender-specific, predominantly occurring in females. Similarly, women who suffered from IBD and who were older than 40 had a higher risk of myocardial infarction (1.6 HR, P=0.003) whereas IBD patients as a whole did not [14].

Cerebrovascular events

Only CD, but not UC, was associated with an increased risk of cerebrovascular disease in the study by Bernstein et al. (1.32 IRR; 95% CI, 1.05-1.66) [10] while in another report, female CD and also UC patients under the age of 40 had a significant risk for stroke (2.1 HR, P=0.04) [14]. This finding corroborated results by Andersohn et al. who described that CD patients below the age of 50 had a significantly higher risk of stroke (2.93 OR; 95% CI, 1.44-5.98) than older CD patients (0.99 OR; 95% CI, 0.75-1.30), however, the results were not specific for genders [15]. After adjusting for potential confounders, a meta-analysis of five studies revealed a 18% higher risk of cerebrovascular events in both CD and UC with no significant differences between the two forms but a higher risk for females than men (1.28 OR adjusted, 95% CI,1.17-1.41) [2].

Peripheral arterial events

Only two studies so far addressed the presence of peripheral arterial events in IBD [10, 14]. Meta-analysis did not reveal a significant increase in the risk for peripheral arterial events [2].

The highest arterial thromboembolic events in people with IBD were reported for mesenteric ischemia [14]. In the study which included 17,487 IBD patients and 69,948 controls, IBD patients showed a largely increased risk of acute mesenteric ischemia (11.2 HR, P<0.001) [14]. A similar result was observed in hospitalized IBD patients in a cross sectional study using a nationwide inpatient sample database showing a strong association between IBD and mesenteric ischemia (3.4 OR adjusted; 95% CI, 2.9-4.0) and venous thrombotic diseases (1.38 OR adjusted; 95% CI, 1.25-1.53) [8].

Observations not supporting an association of IBD with cardiovascular diseases

The latter study also investigated other cardiovascular diseases, e.g. CAD, cerebrovascular occlusion and peripheral vascular disease, however, no increased risk due to IBD was observed [8]. They even found an inverse relationship between these diseases and IBD. In a different report using unadjusted analysis, patients with UC had significant higher risk of first time myocardial infarction as compared to control subjects but not after adjusting to traditional cardiovascular risk factors while CD patients did not show an increased risk either unadjusted or adjusted [16]. It should be noted that the IBD group in this study was slightly but significantly older than the control group.

Two meta-analyses covering studies between 1965 and 2006 [17] and between 1941 and 2011 [18] that addressed IBD as a risk factor of cardiovascular mortality did not reveal an association. Rates of death were increased in patients with IBD but the increase was seen in deaths of all causes such as in colorectal-cancer, pulmonary disease, and nonalcoholic liver disease, rather than in cardiovascular diseases [18]. However, this does not necessarily exclude an association between cardiovascular diseases and IBD since the end point “cardiovascular mortality” may only indirectly represent cardiovascular disease. IBD primarily affects young people who would probably be under medical surveillance early in life and would therefore receive anti-ischemic medication promptly which may significantly prolong their survival. Thus, instead of cardiovascular death, ischemic events during life may represent more reliable surrogates. Typical cardiovascular risk factors other than hypertension have not been confirmed in IBD [19], an observation which probably suggests successful anti-ischemic treatment of IBD patients.

Possible links between IBD and cardiovascular diseases

Inflammatory mediators

IBD is associated with deregulation and increase in various cytokines [20]. Higher levels of these inflammatory mediators may play a role in atherogenesis at any stage. Mediators could flood the circulation and impair endothelium-dependent dilation thus favoring atherosclerosis [21]. Among specific downstream markers of inflammation is CRP which is highly elevated in serum of IBD patients in comparison to healthy controls [22]. CRP predicts cardiovascular events as previously shown by Ridker et al. [23] and may contribute to atherogenesis [24]. Although CRP is regarded as a strong biomarker for cardiovascular events convincing data on the role of CRP in atherogenesis are still missing [25].

Other typical proinflammatory mediators involved in IBD are tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). In particular, TNF-α is a proatherogenic cytokine [26] because blockade of TNF-α with infliximab ameliorated severity of CD [27] and improved endothelial dysfunction in CD patients [22]. VEGF is induced in microvascular cells and may contribute to IBD by increasing angiogenesis and inflammation [28]. VEGF worsens atherosclerosis although beneficial effects through collateral vessel formation have been proposed as well [29].

Endothelial dysfunction and carotid intimal media thickness (IMT)

Endothelial dysfunction is an important event in the development of atherosclerosis [30]. In a recent study, Roifman et al. assessed shear stress (in reactive hyperemia), pulse arterial tonometry and brachial artery flow-mediated dilation to determine micro- and macrovascular functions in IBD patients [31]. They found evidence for microvascular dysfunction in both CD and UC patients but for macrovascular dysfunction, no differences were seen between IBD patients and controls. Other groups, however, reported significantly decreased brachial artery flow-mediated vasodilatation in IBD [32, 33]. In UC, endothelial dysfunction was also shown to be dependent on the severity of the disease [32].

Another surrogate marker for atherosclerosis is intimal media thickening (IMT) of the carotid artery. In two studies the carotid IMT was measured in IBD cohorts vs. controls and both of them revealed a significant increase in carotid IMT [34, 35]. Van Leuven et al. reported increased carotid IMT in a CD cohort and a mixed IBD group (18 UC and 34 CD) [36]. Also Papa et al. demonstrated that the mean carotid IMT value was significantly higher in IBD patients (0.63 ± 0.15 mm) than in controls (0.53 ± 0.08 mm) (P = 0.008) [37]. In line with these results, higher carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity values (parameter indicating arterial stiffness; [38]) were recorded from IBD patients than from controls [39]. The values were independent of traditional cardiovascular risk factors. Although these results favor an association of atherosclerosis and IBD, two studies failed to observe an association between IMT and IBD in a mixed IBD (25 CD and 23 UC) [33] and single CD cohort [40]. Also Maharshak et al. failed to identify IBD as a risk factor for IMT [41]. Thus, a first meta-review on carotid IMT in IBD patients provided only inconclusive results [42].

Endotoxins and the gut microbiom

The idea that atherosclerosis is caused by infection dates back many years [43]. The hypothesis holds that lipoproteins are part of the innate immune system that capture microorganisms and endotoxins by building aggregates that block vasa vasorum which then leads to plaque formation [44]. With the description of the gut microbiom and the awareness of its importance in the development of IBD [45], the idea has now gained more interest [46]. Inflammation of the colon, as in IBD, disrupts the intestinal barrier and allows microbial products such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and other endotoxins to translocate the mucosa and enter the circulation. As a fact, IBD patients do have elevated levels of LPS which correlate with disease activity as demonstrated in patients with UC [47]. High levels of LPS may induce expression of proinflammatory cytokines that contribute to endothelial damage and foam cell formation [48]. Thus, endotoximia has been suggested as a strong risk factor for early atherosclerosis [49]. Among its actions, LPS affects oxidation of LDL [50] by stimulating its oxidation, making it toxic for human endothelial cells [51]. It also activates macrophages thereby accelerating atherosclerosis [52].

The microbial effect on atherogenesis could be mediated via Toll-like receptors 2 (TLR2) and 4 (TLR4) since they are strongly increased in atherosclerotic plaques [53]. Expression of TLR2 and TLR4 are increased on circulating monocytes in acute myocardial infarction and unstable angina patients as compared to healthy control patients [54, 55]. In addition, in vitro studies showed that TLR2 agonists induced significantly higher amounts of TNF-α in monocytes of IBD patients than in control subjects while TLR2 expression was also increased in monocytes of these patients [56]. TLR4 polymorphism was associated with a decreased risk of atherosclerosis [57] suggesting that TLR2 and 4 could be in fact a link between endotoxins and cardiovascular disease. However, in a larger study, no association was found between TLR polymorphism and carotid artery IMT [58]. It is, therefore, still unclear whether TLRs are valuable markers for atherosclerotic risk. Whether a higher endotoxin level in IBD patients may be involved in CAD also remains unclear but a very recent study in rats revealed that antibiotic treatment led to smaller myocardial infarcts and improved recovery of postischemic mechanical function as compared with untreated controls [59].

Lipoproteins

Since oxidized LDL promotes atherosclerosis and cytokine release, studies were conducted to investigate lipids in IBD patients. Pediatric CD patients have highly disturbed lipid profiles together with triacylglycerol depletion and increased protein content in VLDL [60]. In a large retrospective review of medical records of patients diagnosed with IBD between 2000 and 2007 at an academic medical center, significantly lower total cholesterol and HDL-C (cholesterol associated with HDL particles) and higher LDL-C (cholesterol associated with LDL particles) were reported in IBD patients [61]. A persistently low level of HDL-C in chronic infection and inflammation may be undesirable because data from epidemiological studies have shown a greater risk of CAD in subjects with low HDL-C levels and there is mounting evidence that inflammation markedly changes HDL functionality independent of HDL-C levels [62]. Phospholipid depletion and enrichment of HDL with pro-inflammatory proteins like serum amyloid A or apolipoprotein C-III generate dysfunctional or even pro-atherogenic forms of HDL [62]. A study by Ripolles et al. showed that, in subjects with active IBD, inflammation leads to alterations in lipid, apolipoprotein, and lipoprotein profiles and reduced cholesterol efflux capability of serum [63], a metric of HDL functionality and important cardiovascular risk factor [64]. The changes seen in the lipoprotein profile and the reduced cholesterol efflux in adult IBD patients were similar to the changes seen that lead to atherosclerosis and cardiovascular events [63].

The findings of altered lipid profiles from these studies fuel the idea that IBD patients are at higher risk for atherosclerosis than healthy subjects. However, it is presently not clear what the underlying mechanism is and whether malabsorption or systemic inflammation plays a major role in it. High content of inflammatory cytokines in IBD patients may alter de novo synthesis and degradation of lipids and thus would lead to the altered lipoprotein profile [65]. It has been further suggested that lipid-lowering agents such as statins may be beneficial in IBD [66] because they have been shown to reduce CRP levels and thrombus formation [23]. In fact, experimental data on mouse colitis models suggest an anti-inflammatory role of atorvastatin [67]. In a retrospective study of 1,986 statin-exposed and 9,871 unexposed subjects, atorvastatin was found to significantly reduce steroid intake in IBD patients while statin-associated reduction of other hazards (use of anti-TNF agents, abdominal surgery, and hospitalization) failed to reach statistical significance [68].

Hypercoagulability and the CD40/CD40L system

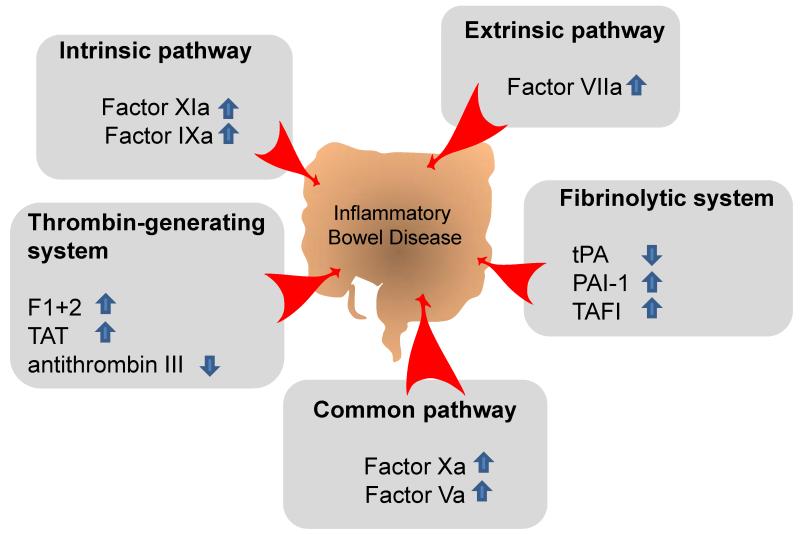

One important factor linking IBD with cardiovascular disease is hypercoagulability. Many abnormalities of the coagulation system and its cellular elements have been described in IBD [4]. Fig. 1 summarizes coagulation abnormalities found in IBD patients. Because of the formation of thrombi at sites of atherosclerotic plaque ruptures, abnormalities in the coagulation cascade and their cellular components are not only important for the development of venous but also arterial thromboemboli [3]. Prothrombin fragments, thrombin-antithrombin complexes, fibrinogen, activated factor XI, IX, VIII and V were all significantly elevated in patients with active UC as compared to patients in quiescent phase [69]. A decrease in the thrombin inhibitor antithrombin III is also prevalent in IBD patients [70] and occurs together with a diminished ability of fibrinolysis. The question of fibrinolysis has been addressed by DeJong et al. and others who showed that levels of tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) were reduced but those of plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI) were increased in IBD [71, 72]. From platelets it is known that they cooperate with leukocytes during leukocyte recruitment into inflamed tissue. Platelet-leukocyte aggregates that are sensitive to thiopurine treatment form during IBD [73]. These aggregates are thought to provide a surface for both coagulation and inflammation. Activated platelets express adhesion proteins such as P-selectin that may support leukocyte rolling on surface-adherent platelets [74]. IBD patients exhibit an increased amount of activated circulating platelets and platelet aggregates that could contribute to an increased risk of thromboembolism [75]. This is of considerable interest regarding the CD40 ligand which is expressed on activated platelets and immune cells [76]. CD40 ligand induces inflammation of the endothelium [77] and blockade of the CD40/CD40L system has been shown to reduce atherogenesis in mice [78]. IBD patients have increased plasma levels of soluble CD40 ligand which reflects increased release of CD40 ligand from platelets [79]. Taken together, platelet-leukocyte interaction and an increased CD40/CD40L system may be important links in the generation of atherosclerosis and IBD. For an in depth review on coagulability and IBD see Scaldaferri et al. [4].

Fig. 1. Abnormalities in the coagulation cascade in inflammatory bowel diseases(IBD).

Aberrant levels of coagulation factors are found in IBD patients that may lead to hypercoagulability. The coagulation cascade can be devided in an intrinsic, extrinsic and common pathway. Fibrinolysis (Fibrinolytic system) and thrombin generation (Thrombin-generating system) takes also part in the coagulation system [4]. Within the extrinsic pathway, higher levels of factor VIIa has been been found in IBD patients vs. quiescent patients [69] while in the intrinsic pathway, Factors XIa and IXa were found elevated in ulcerative colitis (UC) patients vs. patients with inactive UC [69]. Additionally, Factors Va and Xa of the common pathway showed higher levels in active vs. inactive UC [69]. Within the thrombin generating system, prothrombin fragments 1+2 (F1+2) and the thrombin-antithrombin complex (TAT) were also significantly elevated in IBD patients vs. patients in quiescent phase [69] whereas thrombin inhibitor antithrombin III was decreased [70]. Within the fibrinolytic system, inhibitor of plasminogen activator-1 (PAI-1) and thrombin-activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor (TAFI) were increased while tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) was decreased in IBD patients vs. healthy controls [71, 72, 94] suggesting promotion of prothrombotic mechanisms in IBD.

Homocysteine

A deranged homocysteine metabolism has been implicated in atherogenesis [80]. In a population-based prospective cohort study, plasma homocysteine was found to be higher in subjects with preexisting cardiovascular disease than in subjects without it [81]. Homocysteine is produced from methionine and a study by Kanani et al. shows that experimentally-increased homocysteinemia by oral methionine overload leads to endothelial dysfunction as measured by forearm blood flow [82]. Homocysteine may damage the endothelium through generation of oxidative stress, by inhibition of vasodilator properties of nitric oxide synthase and by inciting the release of cytokines [83]. IBD patients typically have high levels of homocysteine in plasma [84] and colon mucosa [85] where it may contribute to colon inflammation [86]. Plasma homocysteine levels were also found to be higher in IBD patients with active disease than in those in remission [87]. These observations suggest a role for homocysteine in atherogenesis of IBD patients. In support of this idea, homocysteine levels in patients with a history of arterial and venous thromboembolic events were investigated before and after methionine loading [88]. The group found a significant increase in homocysteine after methionine loading in the IBD arterial thrombosis group as compared to IBD controls. The results have been challenged by a meta-review that did not indicate a higher risk of hyperhomocysteinemia among IBD patients who had a history of thromboembolic complications [84]. Because of the low number of studies (only four) and IBD patients included in the meta-review, the authors rightfully pointed out that, regarding the risk of hyperhomocysteinemia-related thrombosis in IBD, firm evidence-based conclusions could not have been drawn from the available data [84].

Conclusion and future perspectives

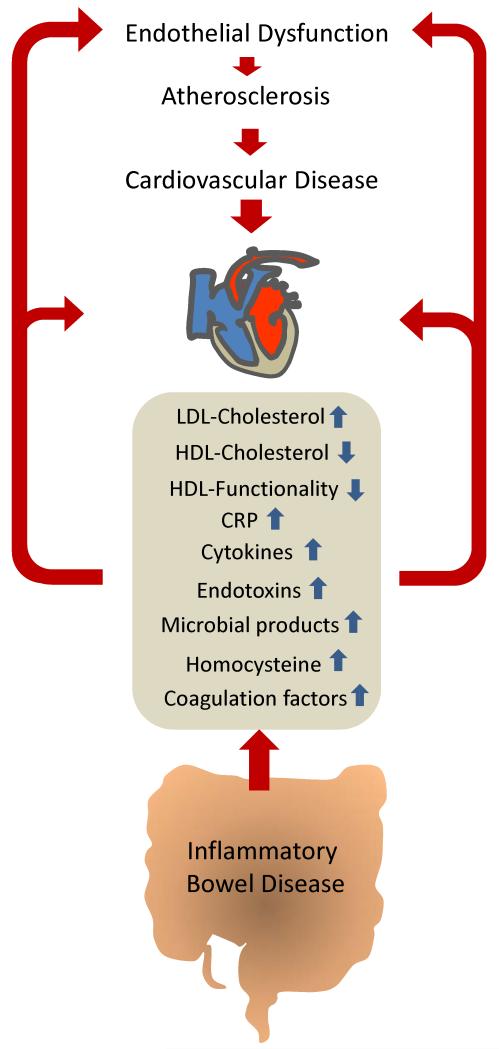

In summary, there is convincing evidence that IBD is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events. Though the number of publications on this topic is limited and despite the lack of prospective studies, the evidence is multifold and strong. The available evidence supports that IBD is associated with CAD, myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular ischemic events and mesenteric ischemia. Stronger epidemiological data and timely prospective studies are needed to substantiate the risk, since depending on the risk increase, special attention or even surveillance may be necessary. The mechanisms behind the increased cardiovascular risk associated with IBD are still unknown. Most of the presently available data suggests that inflammation or consequences of the systemic inflammation may contribute. Pivotal studies demonstrate endothelial dysfunction and increased IMT are involved. The role of systemic inflammatory mediators seems self-evident but clarifying studies are necessary to reveal the involved mechanisms. Further attention is also required to detail the mechanisms behind the dyslipidemia in IBD since dyslipidemia is a well-established cardiovascular risk factor and IBD patients may benefit from medications altering the lipoprotein profile. Additional changes in IBD like hypercoagulability and hyperhomocysteinemia may contribute to the increased cardiovascular risk but these associations are less well established. Fig. 2 summarizes potential links between IBD and cardiovascular disease.

Fig. 2. Potential factors linking inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) with cardiovascular disease.

Cytokines, C-reactive protein (CRP) and LDL-cholesterol are increased in patients with IBD and may promote atherogenesis and cardiovascular disease. Decreased levels of HDL-cholesterol observed in IBD patients and impaired HDL functionality may contribute as well. A further characteristic of IBD is a leaky mucosal barrier. Microbial products and endotoxins could translocate through the colon mucosa and enter the circulation to directly activate immune cells and endothelial cells thus contributing to atherosclerosis. IBD patients also exhibit high levels of homocysteine and coagulation factors known to be implicated in atherosclerosis and thrombus formation.

With regard to cardiovascular diseases, commonalities with other chronic inflammatory diseases like rheumatoid arthritis (RA), for which a strong link to cardiovascular diseases has been established [89], exist. Similar to IBD, RA patients display elevated levels of inflammatory markers, such as TNF-α, IL-6 and, in particular, CRP [90]. RA patients also show increased arterial stiffness [91] and elevated levels of homocysteine [92]. A recent literature analysis has revealed findings of coagulation abnormalities and increased platelet masses in RA patients suggesting similar mechanisms in the generation of cardiovascular disease between IBD and RA [93].

Finally it has to be considered that also short and long term medications used in the treatment of IBD may contribute to the increased cardiovascular risk. Future studies on the impact of IBD on cardiovascular disease and the underlying mechanisms are imperative since with a better understanding we may be able to proactively avoid cardiovascular events in this patient population.

Acknowledgements

RS and GM are supported by grants from the Austrian Science Fund (FWF P 22771 and P 25633 to RS; P22976 to GM). MS is supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG).

Abbreviations

- 5-ASA

5-aminosalicylic acid

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- CD

Crohn’s disease

- CI

confidence interval

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- HDL

high-density lipoprotein

- HDL-C

HDL-cholesterol

- HR

hazard risk

- IBD

inflammatory bowel disease

- IRR

incidence rate ratio

- IL-6

interleukin 6

- IL-1β

interleukin 1 beta

- IMT

intimal media thickness

- LDL

low-density lipoprotein

- LDL-C

LDL-cholesterol

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- OR

odds ratio

- P

probability

- PAI-1

inhibitor of plasminogen activator-1

- TAFI

thrombin-activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor

- TAT

thrombin-antithrombin complex

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor alpha

- TLR2

Toll-like receptor 2

- TLR4

Toll-like receptor 4

- tPA

tissue plasminogen activator

- UC

ulcerative colitis

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- VLDL

very low density lipoprotein

Footnotes

Conflict of interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Tan VP, Chung A, Yan BP, Gibson PR. Venous and arterial disease in inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:1095–113. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Singh S, Singh H, Loftus EV, Jr, Pardi DS. Risk of Cerebrovascular Accidents and Ischemic Heart Disease in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:382–93.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hansson GK. Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1685–95. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Scaldaferri F, Lancellotti S, Pizzoferrato M, De Cristofaro R. Haemostatic system in inflammatory bowel diseases: new players in gut inflammation. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:594–608. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i5.594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Novacek G, Weltermann A, Sobala A, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease is a risk factor for recurrent venous thromboembolism. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:779–87. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Grainge MJ, West J, Card TR. Venous thromboembolism during active disease and remission in inflammatory bowel disease: a cohort study. Lancet. 2010;375:657–63. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61963-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Saleh T, Matta F, Yaekoub AY, Danescu S, Stein PD. Risk of venous thromboembolism with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2011;17:254–8. doi: 10.1177/1076029609360528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Sridhar AR, Parasa S, Navaneethan U, Crowell MD, Olden K. Comprehensive study of cardiovascular morbidity in hospitalized inflammatory bowel disease patients. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:287–94. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Miehsler W, Reinisch W, Valic E, et al. Is inflammatory bowel disease an independent and disease specific risk factor for thromboembolism? Gut. 2004;53:542–8. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.025411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Bernstein CN, Wajda A, Blanchard JF. The incidence of arterial thromboembolic diseases in inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:41–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Yarur AJ, Deshpande AR, Pechman DM, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease is associated with an increased incidence of cardiovascular events. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:741–7. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Haapamäki J, Roine RP, Turunen U, Färkkilä MA, Arkkila PE. Increased risk for coronary heart disease, asthma, and connective tissue diseases in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:41–7. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Rungoe C, Basit S, Ranthe MF, et al. Risk of ischaemic heart disease in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a nationwide Danish cohort study. Gut. 2013;62:689–94. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Ha C, Magowan S, Accortt NA, Chen J, Stone CD. Risk of arterial thrombotic events in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1445–51. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Andersohn F, Waring M, Garbe E. Risk of ischemic stroke in patients with Crohn’s disease: a population-based nested case-control study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:1387–92. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Osterman MT, Yang YX, Brensinger C, et al. No increased risk of myocardial infarction among patients with ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:875–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Dorn SD, Sandler RS. Inflammatory bowel disease is not a risk factor for cardiovascular disease mortality: results from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:662–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.01018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Bewtra M, Kaiser LM, TenHave T, Lewis JD. Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis are associated with elevated standardized mortality ratios: a meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:599–613. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e31827f27ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Gandhi S, Narula N, Marshall JK, Farkouh M. Are patients with inflammatory bowel disease at increased risk of coronary artery disease? Am J Med. 2012;125:956–62. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Roberts-Thomson IC, Fon J, Uylaki W, Cummins AG, Barry S. Cells, cytokines and inflammatory bowel disease: a clinical perspective. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;5:703–16. doi: 10.1586/egh.11.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Hingorani AD, Cross J, Kharbanda RK, et al. Acute systemic inflammation impairs endothelium-dependent dilatation in humans. Circulation. 2000;102:994–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.9.994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Schinzari F, Armuzzi A, De Pascalis B, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonism improves endothelial dysfunction in patients with Crohn’s disease. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;83:70–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Ridker PM, Danielson E, Fonseca FA, et al. JUPITER Study Group Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C-reactive protein. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2195–207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Jialal I, Devaraj S, Venugopal SK. C-reactive protein: risk marker or mediator in atherothrombosis? Hypertension. 2004;44:6–11. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000130484.20501.df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Grad E, Danenberg HD. C-reactive protein and atherothrombosis: Cause or effect? Blood Rev. 2013;27:23–9. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Sprague AH, Khalil RA. Inflammatory cytokines in vascular dysfunction and vascular disease. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;78:539–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Danese S, Sans M, Scaldaferri F, et al. TNF-alpha blockade down-regulates the CD40/CD40L pathway in the mucosal microcirculation: a novel anti-inflammatory mechanism of infliximab in Crohn’s disease. J Immunol. 2006;176:2617–24. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.4.2617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Scaldaferri F, Vetrano S, Sans M, et al. VEGF-A links angiogenesis and inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease pathogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:585–95.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.09.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Testa U, Pannitteri G, Condorelli GL. Vascular endothelial growth factors in cardiovascular medicine. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2008;9:1190–221. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0b013e3283117d37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Anderson TJ. Nitric oxide, atherosclerosis and the clinical relevance of endothelial dysfunction. Heart Fail Rev. 2003;8:71–86. doi: 10.1023/a:1022199021949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Roifman I, Sun YC, Fedwick JP, et al. Evidence of endothelial dysfunction in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:175–82. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Kocaman O, Sahin T, Aygun C, Senturk O, Hulagu S. Endothelial dysfunction in patients with ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:166–71. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000217764.88980.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Principi M, Mastrolonardo M, Scicchitano P, et al. Endothelial function and cardiovascular risk in active inflammatory bowel diseases. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:e427–33. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Dagli N, Poyrazoglu OK, Dagli AF, et al. Is inflammatory bowel disease a risk factor for early atherosclerosis? Angiology. 2010;61:198–204. doi: 10.1177/0003319709333869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Theocharidou E, Gossios TD, Griva T, et al. Is There an Association Between Inflammatory Bowel Diseases and Carotid Intima-media Thickness? Preliminary Data. Angiology. 2013 doi: 10.1177/0003319713489876. doi: 10.1177/0003319713489876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Van Leuven SI, Hezemans R, Levels JH, et al. Enhanced atherogenesis and altered high density lipoprotein in patients with Crohn’s disease. J Lipid Res. 2007;48:2640–6. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700176-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Papa A, Danese S, Urgesi R, et al. Early atherosclerosis in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2006;10:7–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Laurent S, Cockcroft J, Van Bortel L, et al. European Network for Non-invasive Investigation of Large Arteries Expert consensus document on arterial stiffness: methodological issues and clinical applications. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2588–605. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Zanoli L, Cannavò M, Rastelli S, et al. Arterial stiffness is increased in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Hypertens. 2012;30:1775–81. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3283568abd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Broide E, Schopan A, Zaretsky M, et al. Intima-media thickness of the common carotid artery is not significantly higher in Crohn’s disease patients compared to healthy population. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:197–202. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1235-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Maharshak N, Arbel Y, Bornstein NM, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease is not associated with increased intimal media thickening. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1050–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Theocharidou E, Gossios TD, Giouleme O, Athyros VG, Karagiannis A. Carotid Intima-Media Thickness in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review. Angiology. 2014;65:284–93. doi: 10.1177/0003319713477471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Valtonen VV. Infection as a risk factor for infarction and atherosclerosis. Ann Med. 1991;23:539–43. doi: 10.3109/07853899109150515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Ravnskov U, McCully KS. Infections may be causal in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Am J Med Sci. 2012;344:391–4. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31824ba6e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Manichanh C, Borruel N, Casellas F, Guarner F. The gut microbiota in IBD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;9:599–608. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2012.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Rogler G, Rosano G. The heart and the gut. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:426–30. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].McDonnell M, Liang Y, Noronha A, et al. Systemic Toll-like receptor ligands modify B-cell responses in human inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:298–307. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Howell KW, Meng X, Fullerton DA, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 mediates oxidized LDL-induced macrophage differentiation to foam cells. J Surg Res. 2011;171:e27–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2011.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Wiedermann CJ, Kiechl S, Dunzendorfer S, et al. Association of endotoxemia with carotid atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease: prospective results from the Bruneck Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34:1975–81. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00448-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Maziere C, Conte MA, Dantin F, Maziere JC. Lipopolysaccharide enhancesoxidative modification of low density lipoprotein by copper ions, endothelial and smooth muscle cells. Atherosclerosis. 1999;143:75–80. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(98)00277-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Morel DW, DiCorleto PE, Chisolm GM. Modulation of endotoxin-induced endothelial cell toxicity by low density lipoprotein. Lab Invest. 1986;55:419–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Wiesner P, Choi SH, Almazan F, et al. Low doses of lipopolysaccharide and minimally oxidized low-density lipoprotein cooperatively activate macrophages via nuclear factor kappa B and activator protein-1: possible mechanism for acceleration of atherosclerosis by subclinical endotoxemia. Circ Res. 2010;107:56–65. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.218420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Edfeldt K, Swedenborg J, Hansson GK, Yan ZQ. Expression of toll-like receptors in human atherosclerotic lesions: a possible pathway for plaque activation. Circulation. 2002;105:1158–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Ashida K, Miyazaki K, Takayama E, et al. Characterization of the expression of TLR2 (toll-like receptor 2) and TLR4 on circulating monocytes in coronary artery disease. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2005;12:53–60. doi: 10.5551/jat.12.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Satoh M, Shimoda Y, Maesawa C, et al. Activated toll-like receptor 4 in monocytes is associated with heart failure after acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 2006;109:226–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Cantó E, Ricart E, Monfort D, et al. TNF alpha production to TLR2 ligands in active IBD patients. Clin Immunol. 2006;119:156–65. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Kiechl S, Lorenz E, Reindl M, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 polymorphisms and atherogenesis. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:185–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Labrum R, Bevan S, Sitzer M, Lorenz M, Markus HS. Toll receptor polymorphisms and carotid artery intima-media thickness. Stroke. 2007;38:1179–84. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000260184.85257.2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Lam V, Su J, Koprowski S, et al. Intestinal microbiota determine severity of myocardial infarction in rats. FASEB J. 2012;26:1727–35. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-197921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Levy E, Rizwan Y, Thibault L, et al. Altered lipid profile, lipoprotein composition, and oxidant and antioxidant status in pediatric Crohn disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;71:807–15. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.3.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Sappati Biyyani RS, Putka BS, Mullen KD. Dyslipidemia and lipoprotein profiles in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Lipidol. 2010;4:478–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2010.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Marsche G, Saemann MD, Heinemann A, Holzer M. Inflammation alters HDL composition and function: implications for HDL-raising therapies. Pharmacol Ther. 2013;137:341–51. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Ripollés Piquer B, Nazih H, Bourreille A, et al. Altered lipid, apolipoprotein, and lipoprotein profiles in inflammatory bowel disease: consequences on the cholesterol efflux capacity of serum using Fu5AH cell system. Metabolism. 2006;55:980–8. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Khera AV, Cuchel M, de la Llera-Moya M, et al. Cholesterol efflux capacity, high-density lipoprotein function, and atherosclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:127–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Feingold KR, Grunfeld C. Role of cytokines in inducing hyperlipidemia. Diabetes. 1992;41(Suppl 2):97–101. doi: 10.2337/diab.41.2.s97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Karaahmet F, Basar O, Coban S, Yuksel I. Dyslipidemia and inflammation in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:1806–7. doi: 10.1007/s10620-013-2614-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Aktunc E, Kayhan B, Arasli M, Gun BD, Barut F. The effect of atorvastatin and its role on systemic cytokine network in treatment of acute experimental colitis. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2011;33:667–75. doi: 10.3109/08923973.2011.559475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Crockett SD, Hansen RA, Stürmer T, et al. Statins are associated with reduced use of steroids in inflammatory bowel disease: a retrospective cohort study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:1048–56. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Kume K, Yamasaki M, Tashiro M, Yoshikawa I, Otsuki M. Activations of coagulation and fibrinolysis secondary to bowel inflammation in patients with ulcerative colitis. Intern Med. 2007;46:1323–9. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.46.0237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Souto JC, Martínez E, Roca M, et al. Prothrombotic state and signs of endothelial lesion in plasma of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:1883–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02208650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].De Jong E, Porte RJ, Knot EA, Verheijen JH, Dees J. Disturbed fibrinolysis in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. A study in blood plasma, colon mucosa, and faeces. Gut. 1989;30:188–94. doi: 10.1136/gut.30.2.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Koutroubakis IE, Sfiridaki A, Tsiolakidou G, et al. Plasma thrombin-activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 levels in inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20:912–6. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3282faa759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Irving PM, Macey MG, Shah U, et al. Formation of platelet-leukocyte aggregates in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2004;10:361–72. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200407000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].von Hundelshausen P, Weber C. Platelets as immune cells: bridging inflammation and cardiovascular disease. Circ Res. 2007;100:27–40. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000252802.25497.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Collins CE, Cahill MR, Newland AC, Rampton DS. Platelets circulate in an activated state in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:840–5. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90741-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Davì G, Patrono C. Platelet activation and atherothrombosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2482–94. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra071014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Henn V, Slupsky JR, Gräfe M, et al. CD40 ligand on activated platelets triggers an inflammatory reaction of endothelial cells. Nature. 1998;391:591–4. doi: 10.1038/35393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Mach F, Schönbeck U, Sukhova GK, Atkinson E, Libby P. Reduction of atherosclerosis in mice by inhibition of CD40 signalling. Nature. 1998;394:200–3. doi: 10.1038/28204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Danese S, Katz JA, Saibeni S, et al. Activated platelets are the source of elevated levels of soluble CD40 ligand in the circulation of inflammatory bowel disease patients. Gut. 2003;52:1435–41. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.10.1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Fruchart JC, Nierman MC, Stroes ES, Kastelein JJ, Duriez P. New risk factors for atherosclerosis and patient risk assessment. Circulation. 2004;109(23 Suppl 1):III-15–III-19. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000131513.33892.5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Nurk E, Tell GS, Vollset SE, et al. Plasma total homocysteine and hospitalizations for cardiovascular disease: the Hordaland Homocysteine Study. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1374–81. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.12.1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Kanani PM, Sinkey CA, Browning RL, et al. Role of oxidant stress in endothelial dysfunction produced by experimental hyperhomocyst(e)inemia in humans. Circulation. 1999;100:1161–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.11.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].McCully KS. Homocysteine, vitamins, and vascular disease prevention. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:1563S–8S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.5.1563S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Oussalah A, Guéant JL, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Meta-analysis: hyperhomocysteinaemia in inflammatory bowel diseases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:1173–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Morgenstern I, Raijmakers MT, Peters WH, Hoensch H, Kirch W. Homocysteine, cysteine, and glutathione in human colonic mucosa: elevated levels of homocysteine in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:2083–90. doi: 10.1023/a:1026338812708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Danese S, Sgambato A, Papa A, et al. Homocysteine triggers mucosal microvascular activation in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:886–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41469.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Drzewoski J, Gasiorowska A, Malecka-Panas E, Bald E, Czupryniak L. Plasma total homocysteine in the active stage of ulcerative colitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:739–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Oldenburg B, Van Tuyl BA, van der Griend R, Fijnheer R, van Berge Henegouwen GP. Risk factors for thromboembolic complications in inflammatory bowel disease: the role of hyperhomocysteinaemia. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:235–40. doi: 10.1007/s10620-005-1588-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].del Rincón ID, Williams K, Stern MP, Freeman GL, Escalante A. High incidence of cardiovascular events in a rheumatoid arthritis cohort not explained by traditional cardiac risk factors. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:2737–45. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200112)44:12<2737::AID-ART460>3.0.CO;2-%23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Fan F, Galvin A, Fang L, et al. Comparison of inflammation, arterial stiffness and traditional cardiovascular risk factors between rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease. J Inflamm (Lond) 2014;11:29. doi: 10.1186/s12950-014-0029-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Mäki-Petäjä KM, Hall FC, Booth AD, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis is associated with increased aortic pulse-wave velocity, which is reduced by anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha therapy. Circulation. 2006;114:1185–92. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.601641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Roubenoff R, Dellaripa P, Nadeau MR, et al. Abnormal homocysteine metabolism in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:718–22. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Beinsberger J, Heemskerk JW, Cosemans JM. Chronic arthritis and cardiovascular disease: Altered blood parameters give rise to a prothrombotic propensity. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014;44:345–352. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Saibeni S, Bottasso B, Spina L, et al. Assessment of thrombin-activatable fibrinolysis inhibitor (TAFI) plasma levels in inflammatory bowel diseases. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004t;99:1966–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]