Long-acting antiretroviral therapy (LA-ART) could improve survival of human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients, especially those with barriers to adherence and poor outcomes on daily antiretroviral therapy. The costs of future LA-ART regimens should likely play a substantial role in determining their application.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, long-acting antiretroviral therapy, cost-effectiveness, modeling

Abstract

Background. Long-acting antiretroviral therapy (LA-ART) is currently under development and could improve outcomes for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected individuals with poor daily ART adherence.

Methods. We used a computer simulation model to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of 3 LA-ART strategies vs daily oral ART for all: (1) LA-ART for patients with multiple ART failures; (2) second-line LA-ART for those failing first-line therapy; and (3) first-line LA-ART for ART-naive patients. We calculated the maximum annual cost of LA-ART at which each strategy would be cost-effective at a willingness to pay of $100 000 per quality-adjusted life-year. We assumed HIV RNA suppression on daily ART ranged from 0% to 91% depending on adherence, vs 91% suppression on LA-ART regardless of daily ART adherence. In sensitivity analyses, we varied adherence, efficacy of LA-ART and daily ART, and loss to follow-up.

Results. Relative to daily ART, LA-ART increased overall life expectancy by 0.15–0.24 years, and by 0.51–0.89 years among poorly adherent patients, depending on the LA-ART strategy. LA-ART after multiple failures became cost-effective at an annual drug cost of $48 000; in sensitivity analysis, this threshold varied from $40 000–$70 000. Second-line LA-ART and first-line LA-ART became cost-effective at an annual drug cost of $26 000–$31 000 and $24 000–$27 000, vs $28 000 and $25 000 for current second-line and first-line regimens.

Conclusions. LA-ART could improve survival of HIV patients, especially those with poor daily ART adherence. At an annual cost of $40 000–$70 000, LA-ART will offer good value for patients with multiple prior failures. To be a viable option for first- or second-line therapy, however, its cost must approach that of currently available regimens.

Over the past 2 decades, combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) has produced dramatic survival gains among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected patients in the United States [1, 2]. However, these gains are not fully achieved by patients who are poorly adherent to therapy [3, 4]. An ART formulation designed for infrequent, clinician-observed dosing would eliminate the need for daily adherence, providing a means of attaining the full health benefits of ART for these patients [5].

Nanoparticle-based, long-acting ART (LA-ART) formulations—with the potential for dosing via weekly [6], monthly [7], or 3-monthly injections—are in development to address this need [8]. Numerous LA-ART drugs are currently under investigation; individual drugs have been assessed in vitro [9, 10], in animal models [11–13], and in human subjects [6, 8, 14], and promising ones are being evaluated for use in combination therapy [15, 16]. Whether the additional cost of LA-ART compared to daily oral ART might deliver a good value in the US healthcare context is not well understood.

We sought to assess the clinical impact and cost of various strategies for incorporating LA-ART into HIV treatment, taking into account differences in medication adherence among patients. Given uncertainty about the specific characteristics of future LA-ART regimens, we also evaluated the cost and efficacy requirements that an LA-ART regimen would need to meet to become a cost-effective component of US HIV care.

METHODS

Analytic Overview

We used the Cost-Effectiveness of Preventing AIDS Complication (CEPAC) US model, a widely published microsimulation of HIV disease [17–19], to project the clinical impact of LA-ART, and to define the cost thresholds that would make LA-ART cost-effective in the United States. We evaluated 3 LA-ART strategies, compared with daily ART only: (1) LA-ART for patients with multiple prior virologic failures; (2) LA-ART as second-line therapy, for those failing first-line therapy; and (3) LA-ART as first-line therapy for all patients.

For each strategy, we projected several outcomes: mean quality-adjusted survival (in quality-adjusted life-years [QALYs]), mean cumulative healthcare costs (in 2012 United States dollars [USD]), and the maximum annual cost at which each specific LA-ART strategy would be cost-effective, based on a willingness to pay threshold of $100 000/QALY [20, 21]. We measured cost-effectiveness using the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER), defined as the ratio of each strategy's incremental cost to its incremental quality-adjusted survival benefit. All outcomes are reported at present value, using a 3% annual discount rate for future costs and benefits [22].

CEPAC-US Model

Model Overview

The CEPAC-US model is a patient-level microsimulation of HIV disease progression, treatment, and cost. The model simulates a cohort of individual patients by drawing randomly from user-specified distributions of CD4 cell count, HIV RNA, age, sex, and adherence, and then tracks clinical outcomes and costs as these simulated patients transition through various states of disease progression and treatment. In the absence of ART, patients experience a monthly CD4 decline; lower CD4 counts put them at greater risk of opportunistic diseases and HIV-related mortality [23].

Antiretroviral Therapy

To determine the efficacy of an ART regimen, defined by likelihood of virologic suppression, patients are stratified by adherence: higher rates of adherence are associated with higher probabilities of achieving virologic suppression (Supplementary Appendix).

Patients with virologic suppression experience an increase in CD4 count, reducing their risk of HIV-related morbidity and mortality. After achieving virologic suppression, patients are subject to a risk of treatment failure. This risk is inversely correlated with adherence; highly adherent patients have the lowest probability of treatment failure. Patients with observed viral rebound may be switched to a subsequent ART regimen. Many patients, however, who experience viral rebound on a particular regimen are able to regain viral suppression without needing to switch to a new class of drugs. Our model accounts for this by allowing patients multiple opportunities to regain suppression after rebound on protease inhibitor– or integrase inhibitor–based regimens; we model these resuppression opportunities as additional “lines” of therapy.

Loss to Follow-up

Patients are also at risk for being lost to follow-up (LTFU). While LTFU, patients discontinue ART and experience HIV RNA rebound and CD4 decline. As with ART efficacy, the risk of LTFU depends on adherence, with highly adherent patients at lower risk of being LTFU. Patients have a specified monthly probability of returning to care following LTFU.

Additional model specifications are described in detail elsewhere [19].

Input Parameters

Cohort Characteristics

We simulated a cohort representative of HIV-infected patients at the time of presentation to care in the United States (Table 1): 84% were male, the mean age was 43 years, and mean CD4 count was 320 cells/µL [24]. This reflects a group that is somewhat older and more likely to be male than patients at the time of HIV diagnosis in the United States [32]. The initial viral load distribution was from a recent clinical trial [25].

Table 1.

Base Case Input Parameters

| Parameter | Base Case Value | Range | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial cohort characteristics | |||

| CD4 count, cells/μL, mean (SD) | 320 (280) | 200–500 | [24] |

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 43 (12) | 35–50 | [24] |

| Male/female sex, % | 84/16 | [24] | |

| HIV RNA setpoint, log10 copies/mL, median (IQR) | 4.7 (4.3–5.0) | [25] | |

| Baseline adherence | |||

| Proportion with MPR <50% | 0.03 | [26, 27] | |

| Proportion with MPR 50%–95% | 0.51 | a | |

| Proportion with MPR >95% | 0.46 | ||

| Daily ART | |||

| HIV RNA suppression at 6 mo, overall, % | 83b | 73–92 | |

| Adherence >95% | 91 | 80–100 | [28] |

| Adherence 50% | 46 | ||

| Adherence <5% | 0 | ||

| Virologic failure rate after 6 mo, per 100 PY | |||

| Adherence >95% | 1.6 | ±50% | [28] |

| Adherence 50% | 71.9 | ||

| Adherence <5% | 146.6 | ±50% | |

| Cost per patient-year, 2012 USD | |||

| First-line (NNRTI/PI/INI-based) | $25 000 | [29] | |

| Second- to fourth-line (boosted PI-based) | $28 000 | ||

| Fifth-line (INI-based) | $40 000 | ||

| Sixth-line (INI + MVC or ENF salvage) | $41 000 | ||

| Long-acting ART | |||

| HIV RNA suppression at 6 mo, % | |||

| All adherence levels | 91 | 60–100 | Assumptionc |

| Virologic failure rate after 6 mo, per 100 PY | |||

| All adherence levels | 1.6 | 0–18.1 | Assumptionc |

| Retention in care | |||

| Loss to follow-up rate, per 100 PY | |||

| Adherence >95% | 0.1 | ±50% | [30] |

| Adherence <50% | 84.5 | ±50% | |

| Return to care rate, per 100 PY | 18.1 | ±50% | [31]d |

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; ENF, enfuvirtide; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; INI, integrase inhibitor; IQR, interquartile range; MPR, medication possession ratio; MVC, maraviroc; NNRTI, nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; PI, protease inhibitor; PY, person-year; REACH, research in the access of care among the homeless; SD, standard deviation; STARTMRK, MK-0158 Protocol 021; USD, United States dollars.

a Two distinct adherence distributions were modeled, representing the REACH cohort of marginally housed HIV patients and the STARTMRK clinical trial.

b Overall suppression rates will differ slightly for later lines of ART, as the distribution of adherence levels among patients who fail multiple lines of ART will differ from the initial distribution.

c We assume that all patients receiving long-acting ART will observe an efficacy equal to the efficacy of daily ART among the most highly adherent patients.

d We assume that US HIV patients return to care at approximately half the rate of patients in the Danish HIV Cohort Study.

Adherence and ART Efficacy

The distribution of adherence levels was from studies of HIV-infected patients in the United States, including both commercially insured and Medicaid patients (Supplementary Appendix) [26, 27]. We approximated the reported medication possession ratio levels (mean 89%, standard deviation [SD] 14%) using a logit-normal distribution.

We derived the relationship between adherence and virologic suppression from the long-term virological outcomes on ART cohort (Supplementary Appendix) [28]. HIV RNA suppression at 6 months ranged from 0% to 91% depending on adherence; subsequent rates of treatment failure and viral rebound ranged from 1.6 to 146.6/100 person-years (PY).

Loss to Follow-up

Adherence-specific rates of LTFU were derived to match retention-in-care data from the HIV Research Network [30]. Depending on adherence, LTFU varied from 0.1 to 84.5/100 PY. Starting 6 months after LTFU, patients have a 1.5% monthly probability of returning to care (a rate of 18.1/100 PY); this probability increases to 50% in the month of an acute opportunistic disease [31].

Long-Acting ART

Because LA-ART would eliminate the need for strict adherence to daily dosing, we model LA-ART's efficacy as independent of adherence: all patients on LA-ART have the same suppression probability (91%) and subsequent failure rate (1.6/100 PY) as the most highly adherent patients on daily ART. However, patients must be retained in care to achieve suppression; patients with low adherence are more likely to be LTFU, which puts them at higher risk for LA-ART failure.

Cost

Treatment regimens for the model were consistent with options in current US Department of Health and Human Services ART treatment guidelines [33]. We used a first-line oral ART cost of $25 000/patient-year, based on the average wholesale prices of commonly used nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor–, protease-, and integrase-based regimens from the Red Book Online [29], discounted by 23% to reflect actual prices paid [34]. For subsequent regimens, we used a yearly cost of $28 000, based on the average cost of atazanavir- and darunavir-based regimens [29]. Later regimens represented integrase inhibitor–based therapy and salvage therapy and cost $40 000 and $41 000/patient-year, respectively [29]. We assumed that patients with less than full adherence incur an ART cost proportional to their adherence, defined by medication possession ratio.

Because no LA-ART regimens are currently licensed, we did not assign one cost to LA-ART. Instead, we evaluated the cost-effectiveness of LA-ART at costs ranging from $20 000 to $80 000 to determine the maximum cost at which each LA-ART strategy would be cost-effective at a willingness to pay of $100 000/QALY. A higher value of this maximum cost indicates a more attractive LA-ART strategy.

Sensitivity Analyses

To assess the robustness of the results with respect to parameter uncertainty, we conducted sensitivity analyses on numerous model parameters (Table 1). Due to the absence of data from actual clinical studies—and in keeping with the exploratory nature of this analysis—we defined broad but plausible ranges for sensitivity analysis on some of our input parameters (eg, LTFU due to toxicities and the potential for improved retention in care due to LA-ART). For adherence parameters, we evaluated 2 additional distinct populations with low and high adherence: (1) the research in the access of care among the homeless (REACH) cohort of marginally housed HIV-infected individuals in San Francisco, with mean adherence of 73% (SD, 23%) [35], and (2) participants in the MK-0158 Protocol 021 (STARTMRK) trial, in which approximately 85% of participants had perfect adherence, and approximately 98% had ≥90% adherence [36].

We conducted further sensitivity analyses to assess potential additional benefits and harms of LA-ART. These included: 20% decreases or increases in the rate of LTFU on LA-ART to account for potential increase due to toxicity or improved retention due to the health benefits of therapy; 10% or 20% decreases in the efficacy of subsequent ART regimens following LA-ART, to account for the possible risk of developing drug resistance from sustained residual drug concentrations after regimen discontinuation; and 5% increases or decreases in health-related quality of life on LA-ART, to account for potential benefits of reduced pill burden or toxicity. We also assessed the value of LA-ART in the context of patients presenting to care with very low CD4 counts (mean, 50 cells/µL).

Finally, we tested several modeling assumptions in the analysis, including increasing or decreasing the number of available daily ART regimens, eliminating one line of daily ART in strategies with LA-ART, and varying the number of failure events before providing LA-ART after multiple failures between 3 and 5.

For each assumption, we performed a 2-way sensitivity analysis, varying the relevant parameter concurrently with the annual cost of LA-ART. We report the maximum annual cost at which each LA-ART strategy reaches an ICER of ≤$100 000/QALY.

RESULTS

Survival Benefits of LA-ART

The estimated life expectancy for the overall cohort from ART initiation (at mean age 43) was 23.72 years with daily ART only, 23.87 years with LA-ART for those with multiple prior failures, 23.90 years with second-line LA-ART, and 23.96 years with first-line LA-ART (Table 2). Patients with adherence in the lowest 20% of the cohort had a life expectancy far below the overall cohort, at 13.53 years with daily ART only. The introduction of LA-ART produced more substantial gains in life expectancy among these individuals: life expectancy increased to 14.04 years with LA-ART after multiple failures, 14.17 years with second-line LA-ART, and 14.42 years with first-line LA-ART. Discounted quality-adjusted life expectancy was similar, with LA-ART producing gains of 0.06–0.12 QALYs in the overall cohort depending on strategy, and 0.19–0.43 QALYs among the 20% of patients with the lowest adherence (Table 2).

Table 2.

Survival Benefits of Long-Acting Antiretroviral Therapy

| Clinical Role of Long-Acting ART | Life Expectancy (y, Undiscounted) |

Quality-Adjusted Life Expectancy (QALYs, Discounted 3%/Year) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Patients With Adherence in Lowest 20% | Overall | Patients With Adherence in Lowest 20% | |

| Daily oral ART only | 23.72 | 13.53 | 12.89 | 8.52 |

| Patients with multiple prior failures | 23.87 | 14.04 | 12.95 | 8.71 |

| Second-line therapy | 23.90 | 14.17 | 12.97 | 8.80 |

| Initial therapy for treatment-naive | 23.96 | 14.42 | 13.01 | 8.95 |

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; QALYs, quality-adjusted life-years.

Strategies that delayed provision of LA-ART resulted in fewer patients receiving it, but were more effective at targeting LA-ART to individuals with poor adherence. With LA-ART after multiple failures, 10% of the cohort ever received LA-ART, 50% of whom had adherence in the lowest 20% of the cohort. As second-line therapy, 52% of the cohort received LA-ART, but only 27% of these individuals had adherence in the lowest 20%. As first-line therapy, all patients received LA-ART; by definition, 20% had adherence in the lowest 20%.

Cost and Cost-effectiveness of LA-ART

Mean discounted lifetime cost was $395 000 with daily ART only. In the base case, LA-ART after multiple failures became cost-effective (ICER ≤$100 000/QALY) at a cost of ≤$48 000/patient-year. At this LA-ART cost, mean lifetime cost was $400 000 for LA-ART after multiple failures, $469 000 for second-line LA-ART, and $624 000 for first-line LA-ART (Table 3).

Table 3.

Costs and Cost-effectiveness of Long-Acting Antiretroviral Therapy

| Clinical role of LA-ART | Quality-Adjusted Life Expectancy, QALYs | LA-ART Annual Cost = $48 000 |

LA-ART Annual Cost = $27 000 |

LA-ART Annual Cost = $24 000 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Lifetime Cost, USD | ICER, $/QALY | Average Lifetime Cost, USD | ICER, $/QALY | Average Lifetime Cost, USD | ICER, $/QALY | ||

| Daily oral ART only | 12.89 | 395 000 | … | 395 000 | … | 395 000 | … |

| Patients with multiple prior failures | 12.95 | 400 000 | 100 000 | 393 000 | Cost-saving | 393 000 | Dominated |

| Second-line therapy | 12.97 | 469 000 | 3 399 000 | 395 000 | 100 000 | 386 000 | Cost-saving |

| Initial therapy for treatment-naive | 13.01 | 624 000 | 4 184 000 | 415 000 | 539 000 | 390 000 | 100 000 |

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; LA-ART, long-acting antiretroviral therapy; QALY, quality-adjusted life-year; USD, United States dollars.

Second-line LA-ART became cost-effective when the cost of LA-ART was further reduced to ≤$27 000/patient-year. For first-line LA-ART to be cost-effective, the annual cost had to fall to ≤$24 000. When LA-ART cost $27 000/patient-year, LA-ART after multiple failures was cost-saving; that is, it both increased quality-adjusted survival and reduced total cost compared to daily ART only. At a cost of $24 000/patient-year, second-line LA-ART became cost-saving compared to daily ART only and compared to LA-ART after multiple failures.

Sensitivity Analyses

LA-ART After Multiple Failures

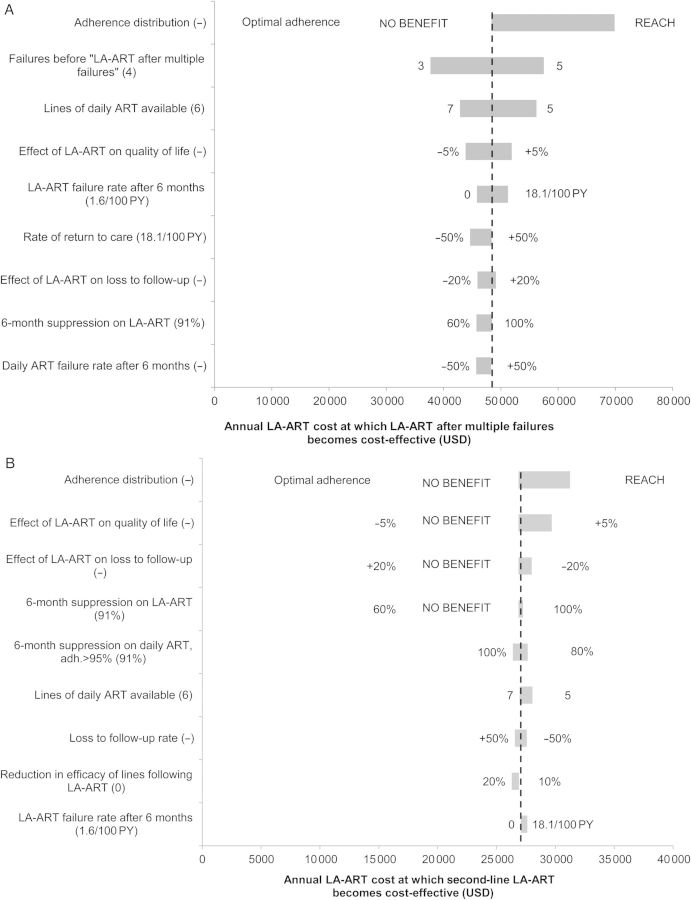

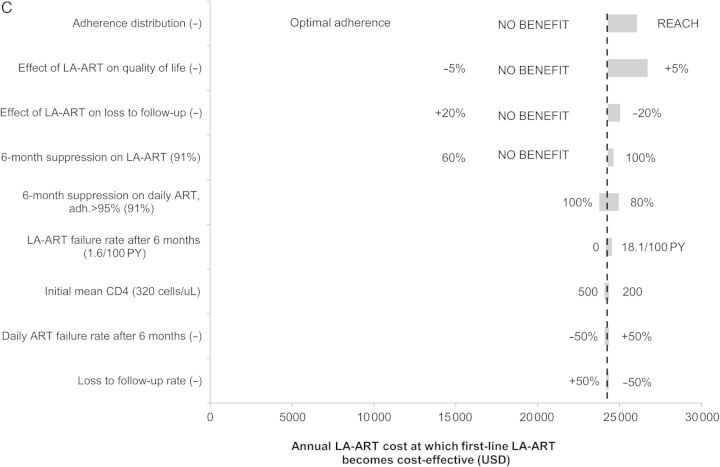

LA-ART after multiple failures led to a greater life expectancy than daily ART under all alternative assumptions except when an optimally adherent population (based on STARTMRK) was simulated. The annual LA-ART cost that would lead to an ICER <$100 000/QALY was influenced by several parameters (Figure 1A). The threshold drug cost was highest, $70 000/year, when simulating a population with adherence similar to the REACH marginally housed cohort (average medication possession ratio = 73%). Two modeling assumptions also had a substantial impact on the threshold cost: When varying the number of regimen failures before providing LA-ART between 3 and 5, the threshold cost ranged from $38 000/year to $58 000/year; when decreasing or increasing the number of available daily ART regimens, the threshold cost ranged from $43 000/year to $56 000/year. Under all other alternative assumptions, the threshold cost was between $44 000/year and $52 000/year.

Figure 1.

Sensitivity analysis on yearly cost at which long-acting antiretroviral therapy (LA-ART) becomes cost-effective. Horizontal bars indicate the range of threshold costs at which each LA-ART strategy reaches an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of $100 000 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) when varying the model parameters shown on the vertical axis. The dotted vertical line in each graph is drawn at the threshold cost at which each LA-ART strategy reaches an ICER of $100 000/QALY under baseline parameter values. A wider bar indicates that varying that parameter produces a greater change in the threshold cost. In parentheses after each parameter name is the base case value of that parameter; at either end of each bar are the parameter values leading to the high/low estimates of the threshold cost. When a particular alternative assumption led to the LA-ART strategy after multiple failures producing no increase in quality-adjusted life expectancy, the threshold cost was not calculated; the parameter value in question is marked NO BENEFIT. The 9 parameters producing the greatest variation in threshold cost for each strategy are shown. Threshold costs (in US dollars [USD]) are shown for LA-ART after multiple failures (A), for second-line LA-ART (B), and for first-line LA-ART (C). Research in the access of care among the homeless (REACH) indicates an adherence distribution based on the Research in Access to Care cohort of marginally housed patients with human immunodeficiency virus in San Francisco [35]. Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; PY, person-year.

Second-line LA-ART

When LA-ART reduced quality of life by 5%, increased LTFU by 20%, or had a 6-month virologic suppression rate of only 60%, second-line LA-ART did not increase quality-adjusted life expectancy compared with daily ART (Figure 1B). When lower overall adherence was simulated, the threshold cost reached its highest value, $31 000/year.

Additional beneficial consequences of the LA-ART regimen led to higher threshold costs: when LA-ART improved quality-of-life by 5% or reduced LTFU by 20%, threshold costs were $30 000/year and $28 000/year. Under all other alternative assumptions, the threshold cost for second-line LA-ART to be cost-effective was between $26 000/year and $28 000/year.

First-line LA-ART

As with second-line LA-ART, first-line LA-ART did not improve quality-adjusted life expectancy under assumptions of low LA-ART efficacy, increased LTFU, or a detrimental impact on quality of life (Figure 1C). The threshold cost for first-line LA-ART to be cost-effective was between $24 000/year and $27 000/year under all other alternative assumptions. The threshold cost increased to $25 000/year when simulating a population with mean CD4 of 50 cells/µL at presentation.

DISCUSSION

We used a mathematical model of HIV disease progression and treatment to investigate the clinical and economic factors that will determine the value of LA-ART for HIV treatment in the United States. We found that LA-ART could offer good value with an annual cost of $48 000 if targeted to poorly adherent individuals with multiple prior virologic failures. LA-ART produced appreciable survival gains in the overall population, but the benefits were greatest among those with low adherence. LA-ART could add almost 1 full year to the life expectancy of patients with poor adherence. Although these patients represent <25% of the population receiving ART in the United States, these substantial survival gains remain clinically meaningful even when averaged across all patients, the majority of whom are unlikely to benefit directly from LA-ART.

Under the alternative assumptions evaluated, LA-ART after multiple failures generally remained cost-effective when the annual cost of LA-ART was <$40 000–$70 000. Even with potential detrimental effects on quality of life, risk of LTFU, or reduced efficacy of subsequent ART due to resistance, LA-ART after multiple failures remained cost-effective at annual LA-ART costs less than approximately $45 000. Notably, this strategy was cost-effective even if 6-month virologic suppression on LA-ART was as low as 60%; this highlights the value of even a modestly effective regimen for individuals with serious barriers to adherence, given their poor prognosis with daily oral regimens [35, 37].

While targeting LA-ART to poorly adherent patients will be crucial if its cost is high, a cost closer to that of currently available oral regimens would support broader use. Across many alternative parameter assumptions, LA-ART became cost-effective as second-line therapy when its cost fell below $26 000–$31 000/year. Even first-line LA-ART was cost-effective if it cost <$24 000/year.

The use of LA-ART could present a dilemma for drug manufacturers and policy makers. Our results suggest that if LA-ART has a high cost, it would be best utilized by targeting to patients with a history of suboptimal ART adherence. Yet providing a more expensive treatment to individuals at greatest risk for poor engagement in care could seem counterintuitive, even if cost-effective. From a public health perspective, however, this approach is more straightforward; to meet the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's goal of increasing the proportion of the HIV-positive population with suppressed viral load [38], interventions for individuals with adherence barriers are needed. Moreover, as poor adherence to ART is associated with unsuppressed viremia and increased transmission risk, improving suppression among this population could have prevention benefits as well.

This study has several limitations. There are currently no data on the efficacy, tolerability, or cost of LA-ART regimens in HIV-infected persons. In our analysis, we have made numerous assumptions about an LA-ART regimen's characteristics, and have examined wide ranges for these characteristics. Our simulation of ART adherence does not explicitly capture the complexities of differential patterns of missed doses [39, 40], variability in adherence over time [41], or associations between adherence and demographic factors [42]. Despite these simplifications, however, our conclusions are robust to alternative model assumptions examined in sensitivity analyses.

We did not conduct analyses for specific subpopulations that may have higher rates of nonadherence and loss to follow-up. Formal assessment of adherence and retention in care may allow LA-ART clinical and insurance coverage decisions to be preferentially focused on populations with greater problems in these 2 areas.

In addition, we did not simulate a strategy of LA-ART for patients who are already virologically suppressed, as used in current clinical trials; we note that if this strategy is the only one studied, it may restrict the potential target population for LA-ART. Finally, our analysis did not assess the impact of LA-ART on HIV transmission; accounting for this additional benefit would likely improve its cost-effectiveness.

Considerations related to implementation of LA-ART regimens on a larger scale should include analysis of the capacity of pharmacies to process these formulations and of clinic staff to administer LA-ART injections, as well as preparing clinics for the additional procedures and protocols needed to provide LA-ART in these settings. Implementation of LA-ART when available, even if it leads to relatively small incremental costs at the individual level, may strain the budgets of payers in aggregate. Budget impact analysis can further inform decisions by specific payers when considering whether to spend their limited resources on this treatment option.

In conclusion, our analysis suggests that LA-ART would improve survival of HIV-infected patients, especially those with barriers to adherence to daily ART. The cost of future LA-ART regimens will play a substantial role in determining their role. At annual costs in the $40 000–$70 000 range, LA-ART will offer good value in patients with multiple prior ART failures. At an annual cost approaching that of currently available regimens, it will also be cost-effective as first-line or second-line therapy.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online (http://cid.oxfordjournals.org). Supplementary materials consist of data provided by the author that are published to benefit the reader. The posted materials are not copyedited. The contents of all supplementary data are the sole responsibility of the authors. Questions or messages regarding errors should be addressed to the author.

Notes

Financial support. Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award number R37AI042006.

Disclaimer. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Walensky RP, Paltiel AD, Losina E, et al. The survival benefits of AIDS treatment in the United States. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:11–9. doi: 10.1086/505147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ray M, Logan R, Sterne JAC, et al. The effect of combined antiretroviral therapy on the overall mortality of HIV-infected individuals. AIDS. 2010;24:123–37. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283324283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wood E, Hogg RS, Yip B, Harrigan PR, O'Shaughnessy MV, Montaner JSG. Effect of medication adherence on survival of HIV-infected adults who start highly active antiretroviral therapy when the CD4(+) cell count is 0.200 to 0.350 X 10(9) cells/L. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:810–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-10-200311180-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lima VD, Harrigan R, Bangsberg DR, et al. The combined effect of modern highly active antiretroviral therapy regimens and adherence on mortality over time. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;50:529–36. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31819675e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swindells S, Flexner C, Fletcher CV, Jacobson JM. The critical need for alternative antiretroviral formulations, and obstacles to their development. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:669–74. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu H, Yao C, Lu R, et al. Albuvirtide, the first long-acting HIV fusion inhibitor, suppressed viral replication in HIV-infected adults [abstract H-554]. Program and abstracts of the 52nd Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy,; San Francisco, CA. 2012. Available at: http://www.abstractsonline.com/Plan/ViewAbstract.aspx?sKey=e1c18d5b-830f-4b4e-8671-35bcfb20eed5&cKey=70d14bcc-bad6-4754-b4b1-66b7d2559a23&mKey=%7B6B114A1D-85A4-4054-A83B-04D8B9B8749F%7D. Accessed 13 August 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verloes R, Van't Klooster G, Baert L, et al. TMC278 long acting—a parenteral nanosuspension formulation that provides sustained clinically relevant plasma concentrations in HIV-negative volunteers [abstract TUPE0042]. Program and abstracts of 17th International AIDS Conference,; Mexico City. 2008. Available at: http://www.iasociety.org/Abstracts/A200717814.aspx. Accessed 13 August 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spreen W, Min S, Ford SL, et al. Pharmacokinetics, safety, and monotherapy antiviral activity of GSK1265744, an HIV integrase strand transfer inhibitor. HIV Clin Trials. 2013;14:192–203. doi: 10.1310/hct1405-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baert L, van't Klooster G, Dries W, et al. Development of a long-acting injectable formulation with nanoparticles of rilpivirine (TMC278) for HIV treatment. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2009;72:502–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nowacek AS, Balkundi S, McMillan J, et al. Analyses of nanoformulated antiretroviral drug charge, size, shape and content for uptake, drug release and antiviral activities in human monocyte-derived macrophages. J Control Release. 2011;150:204–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dash PK, Gendelman HE, Roy U, et al. Long-acting nanoformulated antiretroviral therapy elicits potent antiretroviral and neuroprotective responses in HIV-1-infected humanized mice. AIDS. 2012;26:2135–44. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328357f5ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roy U, McMillan J, Alnouti Y, et al. Pharmacodynamic and antiretroviral activities of combination nanoformulated antiretrovirals in HIV-1-infected human peripheral blood lymphocyte-reconstituted mice. J Infect Dis. 2012;206:1577–88. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van't Klooster G, Hoeben E, Borghys H, et al. Pharmacokinetics and disposition of rilpivirine (TMC278) nanosuspension as a long-acting injectable antiretroviral formulation. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:2042–50. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01529-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jackson AG, Else LJ, Mesquita PM, et al. A compartmental pharmacokinetic evaluation of long-acting rilpivirine in HIV-negative volunteers for pre-exposure prophylaxis. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2014;96:314–23. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2014.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ford SL, Gould E, Chen S, et al. Lack of pharmacokinetic interaction between rilpivirine and integrase inhibitors dolutegravir and GSK1265744. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:5472–7. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01235-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.ViiV Healthcare, GlaxoSmithKline. A study to investigate the safety, tolerability and pharmacokinetics of repeat dose administration of long-acting GSK1265744 and long-acting TMC278 intramuscular and subcutaneous injections in healthy adult subjects. 2013. Available at: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01593046. Accessed 30 June 2014.

- 17.Freedberg KA, Losina E, Weinstein MC, et al. The cost effectiveness of combination antiretroviral therapy for HIV disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:824–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103153441108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schackman BR, Haas DW, Becker JE, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of UGT1A1 genetic testing to inform antiretroviral prescribing in HIV disease. Antivir Ther. 2013;18:399–408. doi: 10.3851/IMP2500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walensky RP, Sax PE, Nakamura YM, et al. Economic savings versus health losses: the cost-effectiveness of generic antiretroviral therapy in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:84–92. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-2-201301150-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cutler D, Rosen A, Vijan S. The value of medical spending in the United States, 1960–2000. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:920–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa054744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Institute of Medicine. Hidden costs, value lost: uninsurance in America. 2003. Available at: http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2003/Hidden-Costs-Value-Lost-Uninsurance-in-America.aspx. Accessed 30 June 2014. [PubMed]

- 22.Weinstein MC, Siegel JE, Gold MR, Kamlet MS, Russell LB. Recommendations of the panel on cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. J Am Med Assoc. 1996;276:1253–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Noubary F, Hughes MD. Assessing agreement in the timing of treatment initiation determined by repeated measurements of novel versus gold standard technologies with application to the monitoring of CD4 counts in HIV-infected patients. Stat Med. 2010;29:1932–46. doi: 10.1002/sim.3955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Althoff KN, Gange SJ, Klein MB, et al. Late presentation for human immunodeficiency virus care in the United States and Canada. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:1512–20. doi: 10.1086/652650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Daar ES, Tierney C, Fischl MA, et al. Atazanavir plus ritonavir or efavirenz as part of a 3-drug regimen for initial treatment of HIV-1. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:445–56. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-154-7-201104050-00316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirsch JD, Gonzales M, Rosenquist A, Miller TA, Gilmer TP, Best BM. Antiretroviral therapy adherence, medication use, and health care costs during 3 years of a community pharmacy medication therapy management program for Medi-Cal beneficiaries with HIV/AIDS. J Manag Care Pharm. 2011;17:213–23. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2011.17.3.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sax PE, Meyers JL, Mugavero M, Davis KL. Adherence to antiretroviral treatment and correlation with risk of hospitalization among commercially insured HIV patients in the United States. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31591. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Messou E, Chaix M-L, Gabillard D, et al. Association between medication possession ratio, virologic failure and drug resistance in HIV-1-infected adults on antiretroviral therapy in Côte d'Ivoire. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;56:356–64. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182084b5a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Red Book online. 2012. Available at: http://www.redbook.com/redbook/online/ Accessed 13 August 2014.

- 30.Fleishman JA, Yehia BR, Moore RD, Korthuis PT, Gebo KA. Establishment, retention, and loss to follow-up in outpatient HIV care. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;60:249–59. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318258c696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Helleberg M, Engsig FN, Kronborg G, et al. Retention in a public healthcare system with free access to treatment: a Danish nationwide HIV cohort study. AIDS. 2012;26:741–8. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834fa15e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV surveillance report: diagnosis of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2011. 2011. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/statistics_2011_HIV_Surveillance_Report_vol_23.pdf#Page=17. Accessed 23 October 2014.

- 33.Department of Health and Human Services Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. 2014. Available at: http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/adultandadolescentgl.pdf. Accessed 23 October 2014.

- 34.Department of Health and Human Services. Medicaid drug price comparisons: average manufacturer price to published prices. 2005. Available at: http://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-05-05-00240.pdf. Accessed 13 August 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bangsberg DR, Ragland K, Monk A, Deeks SG. A single tablet regimen is associated with higher adherence and viral suppression than multiple tablet regimens in HIV plus homeless and marginally housed people. AIDS. 2010;24:2835–40. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328340a209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lennox JL, DeJesus E, Berger DS, et al. Raltegravir versus efavirenz regimens in treatment-naive HIV-1-infected patients: 96-week efficacy, durability, subgroup, safety, and metabolic analyses. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55:39–48. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181da1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Berg KM, Litwin AH, Li X, Heo M, Arnsten JH. Lack of sustained improvement in adherence or viral load following a directly observed antiretroviral therapy intervention. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:936–43. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National HIV prevention progress report, 2013. 2013. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/policies_NationalProgressReport.pdf. Accessed 30 June 2014.

- 39.Genberg BL, Wilson IB, Bangsberg DR, et al. Patterns of antiretroviral therapy adherence and impact on HIV RNA among patients in North America. AIDS. 2012;26:1415–23. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328354bed6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parienti J-J, Das-Douglas M, Massari V, et al. Not all missed doses are the same: sustained NNRTI treatment interruptions predict HIV rebound at low-to-moderate adherence levels. PLoS One. 2008;3:810–6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilson IB, Bangsberg DR, Shen J, et al. Heterogeneity among studies in rates of decline of antiretroviral therapy adherence over time: results from the Multisite Adherence Collaboration on HIV 14 study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;64:448–54. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Simoni JM, Huh D, Wilson IB, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in ART adherence in the United States: findings from the MACH14 study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;60:466–72. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31825db0bd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.