Abstract

Background and purpose

Integration of repaired cartilage with surrounding native cartilage is a major challenge for successful tissue-engineering strategies of cartilage repair. We investigated whether incorporation of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) into the collagen scaffold improves integration and repair of cartilage defects in a cynomolgus macaque model.

Methods

Cynomolgus macaque bone marrow-derived MSCs were isolated and incorporated into type-I collagen gel. Full-thickness osteochondral defects (3 mm in diameter, 5 mm in depth) were created in the patellar groove of 36 knees of 18 macaques and were either left untreated (null group, n = 12), had collagen gel alone inserted (gel group, n = 12), or had collagen gel incorporating MSCs inserted (MSC group, n = 12). After 6, 12, and 24 weeks, the cartilage integration and tissue response were evaluated macroscopically and histologically (4 null, 4 gel, and 4 MSC knees at each time point).

Results

The gel group showed most cartilage-rich reparative tissue covering the defect, owing to formation of excessive cartilage extruding though the insufficient subchondral bone. Despite the fact that a lower amount of new cartilage was produced, the MSC group had better-quality cartilage with regular surface, seamless integration with neighboring naïve cartilage, and reconstruction of trabecular subchondral bone.

Interpretation

Even with intensive investigation, MSC-based cell therapy has not yet been established in experimental cartilage repair. Our model using cynomolgus macaques had optimized conditions, and the method using MSCs is superior to other experimental settings, allowing the possibility that the procedure might be introduced to future clinical practice.

Articular cartilage has a limited capacity for repair, leading to further degeneration without treatment of a defect. A number of surgical options, including microfracture (Redman et al. 2004), osteochondral grafting (Matsusue et al. 1993, Gross et al. 2008), and cell-based techniques such as autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI) (Brittberg et al. 1994) have been developed and are used in clinical settings. However, cartilage injuries treated with microfracturing may deteriorate with time as a result of the high proportion of fibrocartilage (Mithoefer et al. 2009), or a lack of lateral integration between host and donor cartilage may remain after osteochondral grafting (Lane et al. 2004).

With the chondrocyte implantation procedure, the chondrocytes are harvested from the joint and then expanded in vitro. In this process, the cells may dedifferentiate and attenuate their ability to produce collagen type II, the major collagen component of normal hyaline cartilage (Grigolo et al. 2002). One concern in using first-generation ACI was a re-arthroscopy rate of 20–25% during the first 1–2 years (Henderson et al. 2006, Knutsen et al. 2004) where hypertrophy of the repair tissue has been found in most cases.

As an alternative treatment, tissue engineering has been demonstrated to be a promising approach to restoring cartilage defects. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are multipotent progenitor cells that may differentiate into several cell lineages including chondrocytes. MSCs have theoretical advantages over chondrocytes regarding potential for healing. Such cells have the ability to proliferate without losing their ability to differentiate into mature chondrocytes producing collagen II and aggrecan. In the short term, bone marrow-derived MSCs combined with scaffolds have been successful in cartilage repair using animal models such as rabbits (Dashtdar et al. 2011), sheep (Zscharnack et al. 2010), and horses (Wilke et al. 2007).

In this study, we tested the hypothesis that expanded bone marrow-derived MSCs in a collagen scaffold would improve healing of osteochondral injury in a novel animal model using cynomolgus macaques. Since there have been no previous studies using MSCs of primates for cartilage repair, we confirmed pluripotency of the MSCs by differentiation assay after isolation. We then studied in vivo responses to MSC transplantation using a cartilage injury model in the cynomolgus macaque. Cell and tissue responses to the MSC transplantation were evaluated by macroscopic and histological examination at 6, 12, and 24 weeks.

Material and methods

Animal care

18 skeletally mature cynomolgus macaques (approximately 5–7 years old, weighing 7–9 kg) were used. The animals were allowed to move freely in their cages immediately after surgery, and most animals were immediately able to bear weight on both legs. The experiment was performed according to the guidelines for animal research at the Shiga University of Medical Science.

Bone marrow fluid

Bone marrow was harvested under anesthesia induced by intramuscular injection of Ketalar (5 mg/kg). A 4-cm skin incision was made over the anterior aspect of the upper arm under sterile conditions. 2 needles were inserted into the humerus with one end of the extension tube connected to a syringe containing 20 mL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 10 U/mL heparin. The other end of the extension tube was connected to an empty syringe. The PBS was pushed gently from the syringe into the bone marrow cavity to flush out the bone marrow fluid. The medium containing the bone marrow fluid was collected into the syringe, and the process was repeated twice.

Isolation and expansion of MSCs

Harvested bone marrow cells were filtered through a 70-μm nylon filter (Becton, Franklin Lakes, NJ) with remaining tissues discarded. The cells were plated at 5 × 104 cells/cm2 in αMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR), 100 units/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 250 ng/mL amphotericin B, and incubated at 37ºC in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. After 3–4 days, the medium was changed to remove the non-adherent cells and the adherent cells were cultured for another 14 days (passage 0). Then the cells were trypsinized, harvested, and re-seeded at 50 cells/cm2. After 14 additional days of culture, the cells were harvested as passage 1. In order to confirm that the MSCs had colony-forming properties, 100 cells were plated in 60-cm2 dishes, cultured for 14 days, and stained with Giemsa.

In vitro differentiation assay

100 bone marrow cells at passage 1 were cultured for another 14 days. Then pluripotency of the MSCs was confirmed by differentiation assay. For adipogenesis or osteogenesis, the medium was changed either to adipogenic medium (MK429; Adipo-Inducer Reagent, Takara, Otsu Japan) or to osteogenic medium (MK430, Osteoblast-Inducer Reagent, Takara). The cells were cultured for 14 days, with the medium being changed twice a week. The adipogenesis differentiation was confirmed by staining with oil red O solution. The osteogenesis differentiation was confirmed by alkaline phosphatase staining (ALP).

For chondrogenesis, the medium was changed to chondrogenetic base medium (CCM005, human/mouse StemXVivo Chondrogenetic Base Media; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) with supplement (CCM006 human/mouse StemXVivo Chondrogenetic Supplement, R&D Systems). The cells were cultured for up to 14 days with a medium change twice a week. Collected cell pellets were fixed, embedded in paraffin, cut into 5-μm sections, and stained with hematoxylin-eosin (HE) or stained immunohistochemically for type-II collagens.

Biomaterial and preparation of implants

Passage 1 cells were suspended at 1 × 106 cells/mL in αMEM. After incubation for 20 min at 37ºC in 5% CO2, the cells were centrifuged at 450 g for 5 min and washed twice with PBS. They were then mixed with an equal volume of collagen gel (Aterocollagen, 3% type-I collagen; Koken, Tokyo, Japan). The collagen gel-cell mixture was placed in a 6-well plate with 3 mL αMEM and 20% FBS added to the culture for hardening of the gel.

Creation and repair of the osteochondral defects

4 weeks after harvest of bone marrow, the macaques were operated in both knees under sterile conditions and under anesthesia induced by intramuscular injection of Ketalar (5 mg/kg). Through a medial parapatellar incision, a 3-mm diameter and 5-mm deep defect was created over the patellar groove using a stainless-steel punch. Osteochondral defects were created in the patellar groove of 36 knees of 18 macaques. The cartilage defects were either implanted with collagen gel or left untreated. The experimental group implanted with collagen gel containing MSCs was designated the MSC group (n = 12), while the experimental group implanted with collagen gel without MSCs was designated the gel group (n = 12). The experimental group not implanted with collagen gel but left untreated served as a negative control, and was designated the null group (n = 12). The animals were killed at scheduled time points; i.e. after 6, 12, and 24 weeks (corresponding to 4 null, 4 gel, and 4 MSC knees at each time point (Table 1)). Cartilage integration and tissue response were evaluated macroscopically and histologically.

Table 1.

Distribution of implant patterns

| Implant pattern (right – left) | 6-week model 2 animals 4 knees | 12-week model 2 animals 4 knees | 24-week model 2 animals 4 knees |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nulla – Gel | Null – Gel | Null – Gel | Null – Gel |

| (6 animals/12 knees) | Null – Gel | Null – Gel | Null – Gel |

| Gelb – MSCc | Gel – MSC | Gel – MSC | Gel – MSC |

| (6 animals/12 knees) | Gel – MSC | Gel – MSC | Gel – MSC |

| Null – MSC | Null – MSC | Null – MSC | Null – MSC |

| (6 animals/12 knees) | Null – MSC | Null – MSC | Null – MSC |

| Total number of each experimantal design Null / Gel / MSC | 4 / 4 / 4 | 4 / 4 / 4 | 4 / 4 / 4 |

aNull: Osteochondral defects without implants.

bGel: Osteochondral defects implanted with gel alone.

cMSC: Osteochondral defects implanted with gel incorporated with MSC

Postoperative condition and welfare of the animals

After the surgery, the animals were returned to their cages without cast immobilization (macaques bite cast until it breaks off). However, cynomolgus macaques do not normally run about in the standard cage, but sit on a perch set up in the cage. We did not see any great difference in the postoperative behavior between animals that were given different implants. They were killed with an overdose of sodium pentobarbital, and the knees were evaluated by histological examination at 6, 12, and 24 weeks after surgery.

Histological examination

The dissected knees were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, decalcified in 4% EDTA solution, and embedded in paraffin blocks. 5-μm thickness sections were obtained from the center of each defect and stained with toluidine blue. Randomly chosen histological sections were examined under the light microscope for histomorphometrical analysis using Image-Pro Plus (IPP) 6.0 software (Media Cybernetics Inc, Acton, MA). According to the area of positive toluidine blue staining, the percentage of new cartilage tissue area in the cartilage defect area was calculated following the instructions of the software provider (Media Cybernetics). We used the filter function to remove false- positives. The percentage of new cartilage tissue area was calculated as follows: % new cartilage area = (area of new cartilage) / (area of estimated cartilage layer) × 100.

For overall evaluation of the regenerated tissue in the defect area, the repaired tissues were graded blind by 3 observers using Caplan’s histological grading scale (Caplan et al. 1997). In this grading scale, the repair tissue is evaluated in 6 categories, i.e. cell morphology, reconstruction of subchondral bone, matrix staining, filling of defect, surface regularity, and bonding of graft edge. A total of 16 points stands for normal articular cartilage and 0 represents no regeneration.

Immunohistochemical examination for type-I and type-II collagen

The expression of type-I and -II collagens in the reparative tissue was studied immunohistochemically. We used a mouse monoclonal antibody to human type-I and -II collagens that has been verified to cross-react with primate type-I and -II collagens. For the immunohistochemical examination, the sections were stained as previously described (Mimura et al. 2008).

Statistics

Results are expressed as median values and interquartile range (IQR). Kruskal-Wallis test was used to determine significant differences among groups. Any p-value of less than 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

Characteristics of bone marrow-derived MSCs

Cells isolated from the bone marrow of cynomolgus macaques using the present protocol showed a distinct colony-forming property that was compatible with the characteristics of MSCs. It has been long known that isolated MSCs have colony-forming potential (Friedenstein 1976).

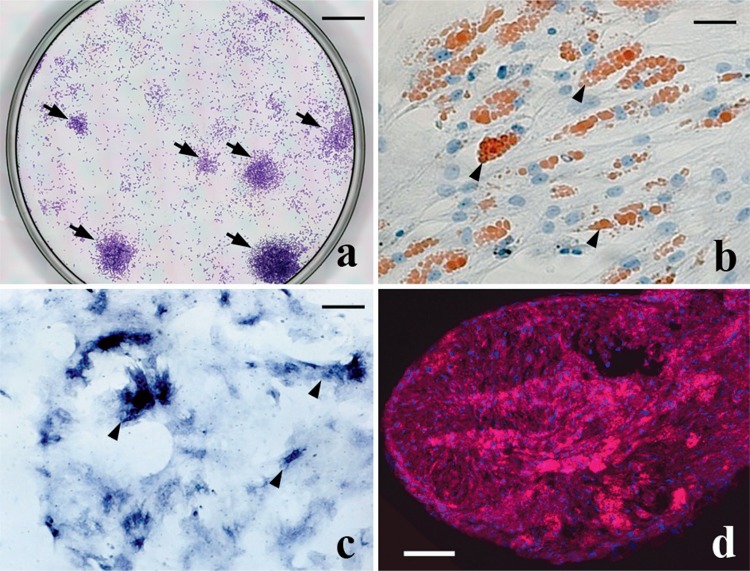

To confirm that the cells isolated represented a group of MSCs, their differentiation potentials were confirmed by differentiation assay. Adipogenic colonies were stained with oil red O, whereas osteogenetic colonies were stained with ALP stain. For chondrogenetic potential, pellets of the cells were stained for type-II collagen by immunostaining (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Characteristics of bone marrow-derived MSCs. Panel (a) demonstrates the colony-forming properties of MSCs isolated from bone marrow of cynomolgus macaques using the present protocol (arrows). Bar: 1 cm. Panel (b) shows the adipogenetic properties of MSC-derived cells from staining of lipid droplets with oil red O (arrowheads). Bar: 20 μm. Panel (c) confirms the osteoblastic properties of MSC-derived cells with alkaline phosphatase staining (arrowheads). Bar: 30 μm. Panel (d) confirms the chondrogenetic properties from immunostaining of type-II collagen. Type-II collagen-positive matrix is stained red. Bar: 0.5 mm.

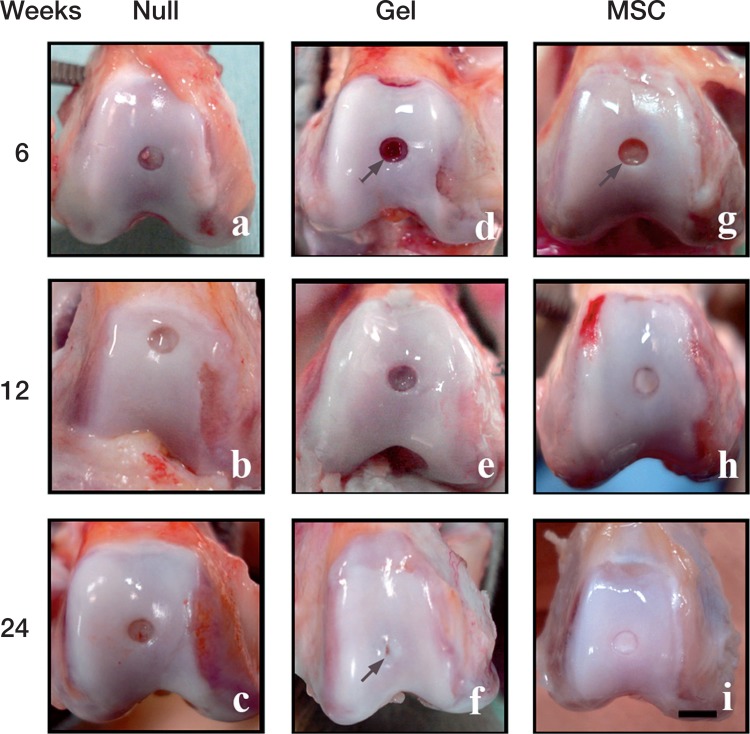

Macroscopic observation (Figure 2)

Figure 2.

Macroscopic observations of the repaired defects in the 3 groups at 6 weeks (a, d, g), 12 weeks (b, e, h), and 24 weeks (c, f, i) after implantation. Scale bar: 5 mm. Arrow in (d): the sharp edge of the defect is visible at 6 weeks in the gel group. Arrow in (f): a hollow-like deformity remains in the central region of the defect, despite thick coverage by the reparative tissue. Arrow in (g): the sharp edge of the defect is also visible in the MSC group at 6 weeks.

We did not observe any severe synovitis, osteophyte formation, or infection in any of the animals. The full-thickness cartilage defects of the null group, which were untreated (without inserting collagen gel), remained uncovered at the different time points of the study (6, 12, and 24 weeks postoperatively). In the cartilage defects of the gel group, sharp edges of the defects were visible at 6 weeks. At 12 weeks, the defects were thinly covered with reparative tissue, with the reddish color of the marrow becoming vague. At 24 weeks, the defect was covered with thick reparative tissue, though the central region of the defects often remained uncovered, with a hollow-like deformity (arrow in Figure 2).

In the MSC group, the sharp edges of the defects were visible at 6 weeks postoperatively. At 12 weeks, the defects were evenly covered with yellowish reparative tissue. At 24 weeks, the defects were covered with watery hyaline cartilage-like tissue similar to the neighboring naïve cartilage.

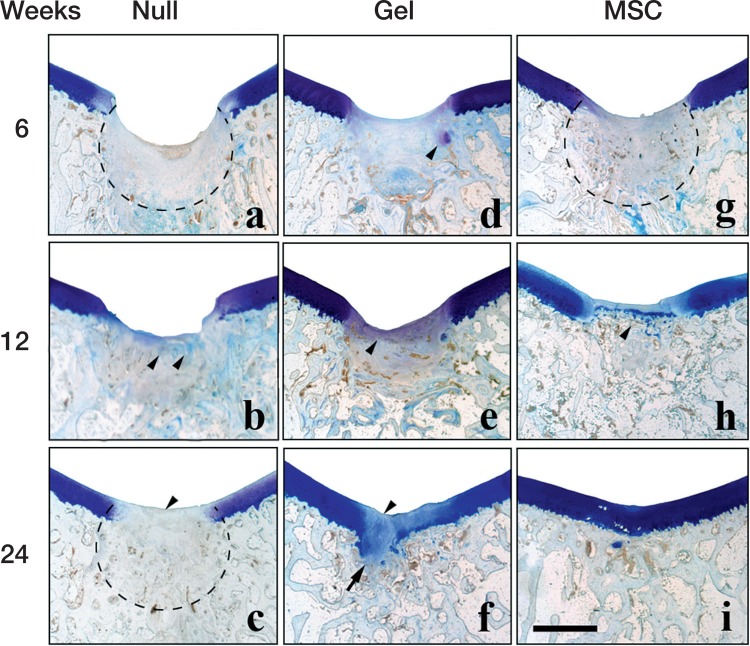

Histological observation by toluidine blue staining (Figures 3 and 4)

Figure 3.

Histological findings after toluidine blue staining in the 3 groups at 6 weeks (a, d, g), 12 weeks (b, e, h), and 24 weeks (c, f, i) after implantation. Scale bar: 2 mm. Dotted line in (a): amorphous reparative tissue filling the subchondral region. Arrowheads in (b): faint toluidine blue staining that reflects involvement of endochondral ossification. Arrowhead in (c): toluidine blue-negative reparative tissue covering the defect. Dotted line in (c): reconstructed subchondral bone consisting of woven bone-like structure. Arrowhead in (d): toluidine blue-positive cartilaginous tissue. Arrowhead in (e): thin faintly toluidine blue-positive layer covering the defect. Arrowhead in (f): the unstained central region of the cartilaginous layer covering the defect. Arrow in (f): excessive cartilage extruding through the deficient tidemark. Dotted line in (g): woven bone-like subchondral bone already re-appearing at 6 weeks. Arrowhead in (h): reconstructed tidemark distinctly discriminating the articular cartilage from the subchondral bone.

Figure 4.

Comparison of all 24-week toluidine blue histology sections. Histological findings after toluidine blue staining of the gel group (a, b, c, d), the null group (e, f, g, h), and the MSC group (i, j, k, l). Scale bar: 3 mm.

The repair process of each experimental group was first evaluated by toluidine blue staining. In the full-thickness defect of the null group, the subchondral region was filled with amorphous reparative tissue at 6 weeks postoperatively, with the cartilage layer uncovered. At 12 weeks, the reparative tissue in the subchondral region was faintly stained with toluidine blue, reflecting involvement of endochondral ossification. At 24 weeks, bone tissue reappeared in the subchondral bone region, although it did not consist of trabecular structure with marrow space but of woven bone-like structure.

In the gel group, the reparative tissue in the subchondral region involved some toluidine blue-positive cartilaginous tissue at 6 weeks. At 12 weeks, the faintly stained layer covered the defect. At 24 weeks, the defect was covered with the cartilaginous layer, although the central region was often faintly stained by toluidine blue. The reconstruction of subchondral bone was often insufficient—lacking any supportive structure for the cartilage layer, and there was excessive growth of cartilage into the subchondral region.

In the MSC group, the trabecular structure of subchondral bone had already reappeared. At 12 weeks, the tidemark structure that discriminates between the articular cartilage and subchondral bone had reappeared. At 24 weeks, the thickness of the toluidine blue-stained cartilage layer was comparable to that of the neighboring naïve cartilage.

Comparison of all 24-week toluidine blue histology sections confirmed that the gel group showed most cartilage-rich reparative tissue covering the defect, owing to formation of excessive cartilage extruding though the insufficient subchondral bone. Despite the lower amount of new cartilage produced, the MSC group showed better-quality cartilage with a regular surface, seamless integration with neighboring naïve cartilage, and reconstruction of trabecular subchondral bone.

Quantitative evaluation

Quantitative histological evaluation showed a statistically significantly higher degree of new cartilage area in the gel and MSC groups at 12 and 24 weeks postoperatively compared to the null group (Table 2). However, there was no significant difference between the gel group and the MSC group.

Table 2.

Percentage of new cartilage area in the experimental groups. Values are median (interquartile range)

| Null group | Gel Group | MSC group | p-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 weeks | 5 (3–7) | 38 (45–44) | 39 (36–46) | 0.02b |

| 24 weeks | 2 (2–4) | 124 (118–130) | 99 (94–104) | 0.007b |

Percentage of new cartilage tissue area was calculated as (area of new cartilage) / (area of estimated cartilage layer) x 100.

aKruskal–Wallis test.

bSignificant difference between Null group and Gel, MSC groups (p < 0.05)

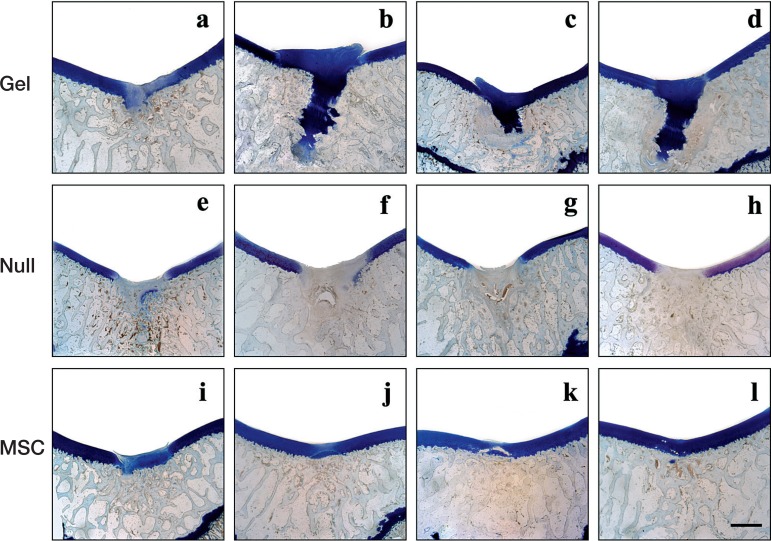

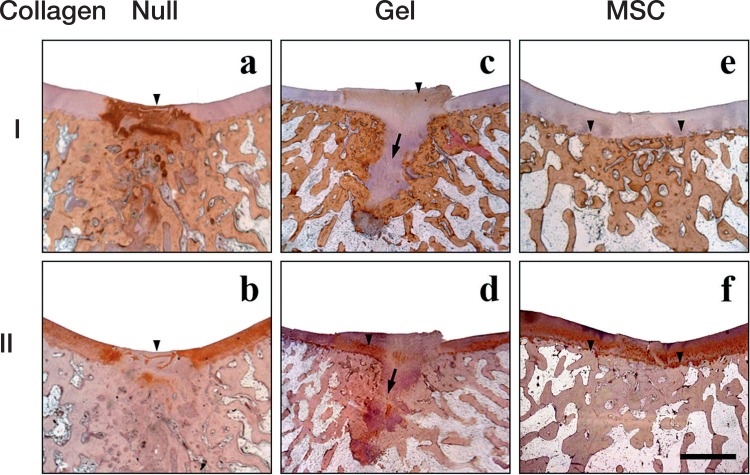

Qualitative histological evaluation for type-I and type-II collagen (Figure 5)

Figure 5.

Histological findings after immunohistochemistry for type-I collagen (a, b, c) and type-II collagen (b, d, f) in the 3 groups 24 weeks after implantation. Scale bar: 2 mm. Immunopositive staining is brown, and immunonegative matrix is stained purple. Arrowhead in (a): intensely collagen type-I positive repair tissue covering the defect. Arrowhead in (b): collagen type-II-void reparative tissue covering the defect. Arrowhead in (c): very faint collagen type-I positivity in the repair tissue. Arrow in (c, d): excessive cartilage extruding through the deficient tidemark. Arrowhead in (d): partly positive collagen type-II immunoreactivity in the repair tissue. Arrowheads in (e, f): formation of distinct tidemark discriminating the articular cartilage and subchondral bone consisting of lamellar bone.

In the null group, the reparative tissue covering the cartilage defect was intensely positive for type-I collagen at 24 weeks. The corresponding region was typically negative for type-II collagen, suggesting that the repair tissue had scar-like properties.

In the gel group, the repair tissue was negative for type-I collagen but positive for type-II collagen, suggesting cartilage-like properties. In accordance with the histological findings from toluidine blue staining, the subchondral bone had no trabecular structure.

In the MSC group, the thickness of the type-I negative and type-II positive layer was consistent with that of the neighboring naïve cartilage. In addition, the type-I positive subchondral bone had a clear outline of the tidemark beneath the regenerated cartilage.

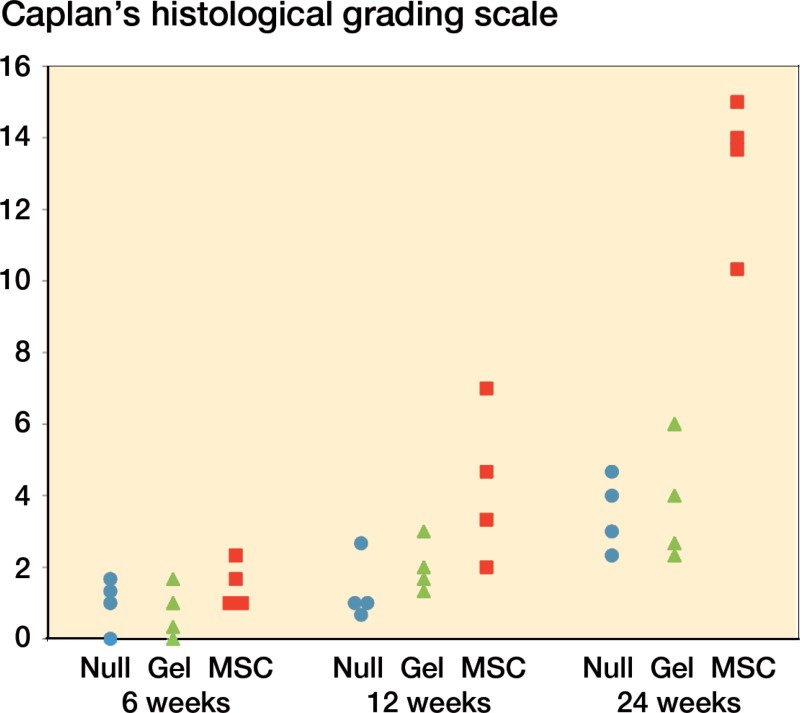

Qualitative histological evaluation by histological scaling (Figure 6)

Figure 6.

Qualitative histological evaluation by Caplan’s histological grading scale. The qualitative histological scores of the MSC group were significantly higher than those of the other 2 groups at 24 weeks (p < 0.05). There were no significant inter-observer differences in this histological grading.

Morphological characteristics of the regenerated cartilage-like tissue were evaluated using Caplan’s histological grading scale (Caplan et al. 1997). The MSC group had the highest points of all the experimental groups for all the time points studied. The qualitative histological scores of the MSC group were significantly higher than those of the other 2 groups at 24 weeks (p < 0.05).

Discussion

The ultimate outcome of cartilage repair depends on seamless integration between the host cartilage and the repair cartilage. MSC-based cell therapy is expected to be a viable alternative for cartilage repair. Bone marrow-derived MSCs combined with scaffolds have been successful in animal models such as rabbits (Dashtdar et al. 2011), sheep (Zscharnack et al. 2010), and horses (Wilke et al. 2007). In the present study, we characterized the repair process of MSC-based cell therapy using another animal model, the cynomolgus macaque.

We defined MSCs as being cells derived from bone marrow cells with the functional capacity for self-renewal and to generate a number of differentiated progeny (Mckay 1997). Since the pioneering work by Friedenstein (1976), the colony-forming-unit fibroblast assay has been one of the standard assays for identification of MSCs, with isolation of the adherent, spindle-shaped cells that proliferate to form distinct colonies. By this method, we first isolated colony-forming cells from primate bone marrow cells. We then confirmed their multipotency in vitro by the differentiation assay.

We found that the gel group had regeneration with more cartilaginous tissue, less fibrous tissue, and higher histological scores than the null group at both 12 weeks and 24 weeks. Our previous studies have shown that the endogenous stem cells arising from the bone marrow can be captured and organized by collagen gel and can participate in cartilage repair (Kubo et al. 2007, Mimura et al. 2008, Nishizawa et al. 2010). However, the number of stem cells that are derived from the local bone marrow is limited. Thus, we believe that the MSC-loaded collagen scaffolds resulted in improved cartilage repair, providing larger numbers of stem cells.

Some authors reported a larger percentage of new cartilage area with MSCs than without MSCs (Guo et al. 2004, Uematsu et al. 2005). However, we did not find such an improvement in the MSC group over the gel group. The higher percentage of new cartilage area in the gel group is likely to have been due to the excessive cartilage protruding into the marrow space. The protruding cartilage was not of the best quality, however, being partly positive for type-I collagen. Thus, our findings support previous findings showing no differences in the percentage of new cartilage area—i.e. amount of neocartilage produced—compared to that without MSCs in a different model (Radice et al. 2000). However, the repaired tissue in the MSC group was macroscopically much smoother and of better quality histologically than in the gel group.

It should be noted that the result of qualitative evaluation of the regenerated cartilage in the MSC group was superior to that in the gel group. The superior quality of the regenerated cartilage in the MSC group was also shown by the absence of type-I collagen and the abundance of type-II collagen. Moreover, complete reconstruction of the tidemark on the subchondral bone and seamless integration with the native cartilage should be noted, despite the lower amount of neocartilage.

A previous study investigating the application of osteogenic MSCs associated with scaffold has also shown that they result in better quality of regenerated cartilage and better quality of subchondral bone (Nakamura et al. 2010). Thus, transplanted MSCs are likely to contribute to the regeneration of subchondral bone, although the present study did not address this issue. Another study is needed to prove the participation of the MSC-derived osteogenic cells in subchondral bone formation, perhaps by labeling of the MSCs for viability. In the present study, the MSC group had superior surfaces, thickness, and quality of the regenerated cartilage as well as better integration of the repair cartilage and the subchondral bone, i.e. tidemark formation. The repair tissues in the null group and gel group were inadequately integrated with the subchondral bone. This indicates that proper regeneration of subchondral bone may contribute to the regeneration of cartilage, and delayed bone formation may have resulted in a lack of appropriate mechanical support for the development of overlying cartilage. These results may give some hints on repairing bone and cartilage defects. The mechanism by which subchondral bone integration is regulated is unclear. An understanding of this mechanism is important because we know that in the long term, if integration with subchondral bone does not occur, the regenerated cartilage may well deteriorate and fail.

We chose to use cynomolgus macaques because the healing potential may depend on the animal species. A high degree of spontaneous healing is known to occur with defects of up to 3 mm diameter in a rabbit model, with less spontaneous healing in larger defects (Shapiro et al. 1993). In the present study, spontaneous repair did not take place in the 3-mm defects of the null group. Our preliminary study had demonstrated that spontaneous repair occurred only with defects up to 2 mm in diameter (data not shown). Although the rabbit is widely studied in experimental cartilage repair and it has also been used previously by our group (Kubo et al. 2007, Mimura et al. 2008, Nishizawa et al. 2010), the healing potential of different animal species, particularly of primates, is of great interest. To obtain a sufficiently long observation time and to keep the number of cynomolgus macaques needed to a reasonable level with enough statistical power, we chose 24 weeks as a suitable time point.

The present study had several limitations. Firstly, we used type-I collagen produced in porcine dermis (Aterocollagen (3% type-I collagen); Koken, Tokyo, Japan). This collagen has been approved for a long time for clinical use and its reliability has been established due to the absence of any antigenicity. We prepared autologous MSCs for the present study, while some of the earlier studies have used allogenic MSCs for the sake of easy handling (Løken et al. 2008). In the clinical setting, however, allogenic MSCs cannot be used—in order to avoid unnecessary graft-versus-host reactions.

We seeded MSCs on the scaffold 12 h before implantation. The provider of Aterocollagen® (Koken) recommended that the collagen gel should be kept in culture medium overnight after mixing with reaction buffer, in order to obtain sufficient hardness—for the sake of handling. In other experimental studies using MSCs in scaffolds, the time from seeding to implantation, when stated, has often been less than 48 h (Redman et al. 2004, Labbe et al. 2011). One reason for choosing a relatively short time interval from seeding to implantation is that differentiation of MSCs into chondrocytes is probably facilitated by local factors in the joint and cartilage. Thus, the time interval of 12 h in the present protocol was appropriate.

Another limitation stems from the use of dependent data. Each animal contributed 2 observations, i.e. MSCs vs gel, MSCs vs null, or gel vs null, which were treated as independent observations in the statistical analysis. Theoretically speaking, each animal should have contributed to only 1 experimental observation, but the number of animals was limited for the sake of animal welfare according to the animal research guidelines of our institute. Thus, we must accept that the p-values that we calculated in the present study were probably inordinately low due to our use of dependent data.

Despite these limitations, we believe that the present study provides valuable information on the influence of MSCs on cartilage regeneration, particularly when using the cynomolgus macaque. The combination of the transplantation of autologous MSCs in collagen gel and traditional strategies gave regeneration of better-quality cartilage with a regular surface, seamless integration with neighboring native cartilage. Also it gave reconstruction of trabecular subchondral bone and tidemark which supports the regenerated cartilage.

However, the percentage of new cartilage area was not improved by adding MSCs to the scaffold (Table 2). Since spontaneous healing probably accounts for the absence of improvement in the percentage of new cartilage area in the MSC group relative to the gel group, another study design using larger defects, e.g. 5 mm in diameter, might result in a more clear-cut difference in the degree of new cartilage between the MSC group and the gel group. Application in larger defects is certainly in line with future clinical use. If MSCs—under optimized conditions—turn out to be superior to chondrocyte implantation in experimental cartilage repair, the procedure should be introduced to clinical practice after well-controlled randomized clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

SA, SI, KO, and YM: design of study, data acquisition, data analysis, interpretation of data, and drafting of the article. HI: data acquisition and analysis. TM: data analysis, and final approval of submitted manuscript. KN, HU, KK, MK, and KM: data acquisition and analysis, and interpretation of data.

No competing interests declared.

We are very grateful to Mrs Yoko Uratani for her skillful technical assistance and to Professor Yoshitaka Murakami, Toho University, for help with statistics. This work was supported by a grant-in-aid from the Japanese Ministry of Science and Education (22500457).

References

- Brittberg M, Lindahl A, Nilsson A, Ohlsson C, Isaksson O, Peterson L. Treatment of deep cartilage defects in the kneewith autologous chondrocyte transplantation . N Engl J Med. 1994;331:889–95. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199410063311401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan AI, Elyaderani M, Mochizuki Y, Wakitani S, Goldberg VM. Principles of cartilage repair and regeneration . Clin Orthop. 1997;342:254–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dashtdar H, Rothan HA, Tay T, et al. A preliminary study comparing the use of allogenic chondrogenic pre-differentiated and undifferentiated mesenchymal stem cells for the repair of full thickness articular cartilage defects in rabbits . J Orthop Res. 2011;29:1336–42. doi: 10.1002/jor.21413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedenstein AJ. Precursor cells of mechanocytes . Int Rev Cytol. 1976;47:327–59. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)60092-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigolo B, Lisignoli G, Piacentini A, Fiorini M, Gobbi P, Mazzotti G, Duca M, Pavesio A, Facchini A. Evidence for redifferentiation of human chondrocytes grown on a hyaluronanbased biomaterial (HYAFF-11): molecular, immunohistochemical and ultrastructural analysis . Biomaterials. 2002;23:1187–95. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(01)00236-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross AE, Kim W, Las Heras F, Backstein D, Safir O, Pritzker KP. Fresh osteochondral allograft for posttraumatic knee defects: long-term followup. Clin Orthop. 2008;466:1863–70. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0282-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X, Wang C, Zhang Y, et al. Repair of large articular cartilage defects with implants of autologous mesenchymal stem cells seeded into beta-tricalcium phosphate in a sheep model . Tissue Eng. 2004;10:1818–29. doi: 10.1089/ten.2004.10.1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson I, Gui J, Lavigne P. Autologous chondrocyte implantation: natural history of postimplantation periosteal hypertrophy and effects of repair-site debridement on outcome . Arthroscopy. 2006;22:1318–24. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2006.07.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutsen G, Engebretsen L, Ludvigsen TC, et al. Autologous chondrocyte implantation compared with microfracture in the knee. A randomized trial . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2004;86:455–64. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200403000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo M, Imai S, Fujimiya M, et al. Exogenous collagen enhanced recruitment of mesenchymal stem cells during rabbit articular cartilage repair . Acta Orthop. 2007;78:845–55. doi: 10.1080/17453670710014653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labbe B, Marceau-Fortier G, Fradette J. Cell sheet technology for tissue engineering: the self-assembly approach using adipose-derived stromal cells . Methods Mol Biol. 2011;702:429–41. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61737-960-4_31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane JG, Massie JB, Ball ST, et al. Follow-up of osteochondral plug transfers in a goat model: a 6 month study . Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:1440–50. doi: 10.1177/0363546504263945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Løken S, Jakobsen RB, Arøen A, et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in a hyaluronan scaffold for treatment of an osteochondral defect in a rabbit model . Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2008;16:896–903. doi: 10.1007/s00167-008-0566-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsusue Y, Yamamuro T, Hama H. Arthroscopic multiple osteochondral transplantation to the chondral defect in the knee associated with anterior cruciate ligament disruption . Arthroscopy. 1993;9:318–21. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(05)80428-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mckay R. Stem cells in the central nervous system . Science. 1997;276:66–71. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimura T, Imai S, Kubo M, et al. A novel exogenous concentration-gradient collagen scaffold augments full-thickness articular cartilage repair . Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008;16:1083–91. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mithoefer K, McAdams T, Williams RJ, Kreuz PC, Mandelbaum BR. Clinical efficacy of the microfracture technique for articular cartilage repair in the knee: an evidence-based systematic analysis . Am J Sports Med. 2009;37:2053–63. doi: 10.1177/0363546508328414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura A, Akahane M, Shigematsu H, et al. Cell sheet transplantation of cultured mesenchymal stem cells enhances bone formation in a rat nonunion model . Bone. 2010;46:418–24. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishizawa K, Imai S, Mimura T, et al. In-advance trans-medullary stimulation of bone marrow enhances spontaneous repair of full-thickness articular cartilage defects in rabbits . Cell Tissue Res. 2010;341:371–9. doi: 10.1007/s00441-010-1020-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radice M, Brun P, Cortivo R, Scapinelli R, Battaliard C, Abatangelo G. Hyaluronan-based biopolymers as delivery vehicles for bone-marrow-derived mesenchymal progenitors . J Biomed Mater Res. 2000;50:101–9. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(200005)50:2<101::aid-jbm2>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redman SN, Dowthwaite GP, Thomson BM, Archer CW. The cellular responses of articular cartilage to sharp and blunt trauma . Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2004;12:106–16. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2002.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro F, Koide S, Glimcher MJ. Cell origin and differentiation in the repair of full-thickness defects of articular cartilage . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1993;75:532–53. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199304000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uematsu K, Hattori K, Ishimoto Y, et al. Cartilage regeneration using mesenchymal stem cells and a three-dimensional poly-lactic-glycolic acid (PLGA) scaffold . Biomaterials. 2005;26:4273–79. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilke MM, Nydam DV, Nixon AJ. Enhanced early chondrogenesis in articular defects following arthroscopic mesenchymal stem cell implantation in an equine model . J Orthop Res. 2007;25:913–25. doi: 10.1002/jor.20382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zscharnack M, Hepp P, Richter R, et al. Repair of chronic osteochondral defects using predifferentiated mesenchymal stem cells in an ovine model . Am J Sports Med. 2010;38:1857–69. doi: 10.1177/0363546510365296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]