Abstract

Background and purpose

In Norway, the proportion of revision knee arthroplasties increased from 6.9% in 1994 to 8.5% in 2011. However, there is limited information on the epidemiology and causes of subsequent failure of revision knee arthroplasty. We therefore studied survival rate and determined the modes of failure of aseptic revision total knee arthroplasties.

Method

This study was based on 1,016 aseptic revision total knee arthroplasties reported to the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register between 1994 and 2011. Revisions done for infections were not included. Kaplan-Meier and Cox regression analyses were used to assess the survival rate and the relative risk of re-revision with all causes of re-revision as endpoint.

Results

145 knees failed after revision total knee arthroplasty. Deep infection was the most frequent cause of re-revision (28%), followed by instability (26%), loose tibial component (17%), and pain (10%). The cumulative survival rate for revision total knee arthroplasties was 85% at 5 years, 78% at 10 years, and 71% at 15 years. Revision total knee arthroplasties with exchange of the femoral or tibial component exclusively had a higher risk of re-revision (RR = 1.7) than those with exchange of the whole prosthesis. The risk of re-revision was higher for men (RR = 2.0) and for patients aged less than 60 years (RR = 1.6).

Interpretation

In terms of implant survival, revision of the whole implant was better than revision of 1 component only. Young age and male sex were risk factors for re-revision. Deep infection was the most frequent cause of failure of revision of aseptic total knee arthroplasties.

Globally, the number of knee arthroplasty operations is increasing. In the USA, the incidence of primary total knee arthroplasty (TKA) has increased from 51 per 105 inhabitants in 1990 (Kurtz et al. 2007) to 215 per 105 in 2008 (Carr et al. 2012). In Sweden, the incidence of knee arthroplasty increased from 115 per 105 inhabitants in 2007 (Robertsson et al. 2010) to 135 per 105 in 2011 (Sundberg et al. 2012). In Norway, the incidence increased from 35 per 105 inhabitants (Furnes et al. 2002) in 1999 to 90 per 105 in 2011 (Furnes et al. 2012).

With an increasing aging population and increase in the use of joint arthroplasty in younger people, the increase in knee arthroplasty surgery will continue (Carr et al. 2012)—as will the need for revision TKA (Kurtz et al. 2007). In the United States, for example, projections suggest that the number of revision TKAs will have increased from 38,000 in 2005 to 268,000 by the year 2030 (Kurtz et al. 2007). In Norway, the revision burden, defined as the ratio of revision arthroplasties to the total number of arthroplasties, increased from 6.9% in 1994 to 8.5% in 2011 (Furnes et al. 2012).

Many studies on knee arthroplasty have been based on data from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register (NAR), but all of them concerned primary TKAs (Furnes et al. 2002, 2007, Lygre et al. 2010a, b, Lygre et al. 2011, Gothesen et al. 2013). No studies on the survivorship and the mode of failure of revision TKAs have been conducted in Norway, even though revision of joint arthroplasties is becoming a challenge both medically and economically (Greidanus et al. 2011). Moreover, different surgical techniques have been described on how to approach revision knee arthroplasties with regard to fixation (Sheng et al. 2006, Whiteside 2006, Beckmann et al. 2011, Cintra et al. 2011), role of constraint and stem use (Fehring et al. 2003, Hwang et al. 2010), and whether or not to resurface the patella (Masri et al. 2006, Patil et al. 2010). However, there have been very few comprehensive studies on the outcome of revision TKA. Thus, the main aim of this study was to analyze the survival rate of revision TKAs and to study the causes of failure of revision TKAs based on data in a national registry. A secondary aim was to determine whether the survival of revision TKAs is influenced by type of fixation, brand of prosthesis, and resurfacing of the patella. The study hypothesis was that type of fixation, brand of prosthesis, and resurfacing of the patella would have no influence on the survival rate of revision TKAs.

Patients and methods

Participants

This study was based on data from the NAR, which has been collecting information on knee arthroplasty operations (both primary and revision operations) since 1994 (Havelin et al. 2000). The NAR has a registration completeness of 99% for primary knee arthroplasties and of 97% for revision knee arthroplasties (Espehaug et al. 2006).

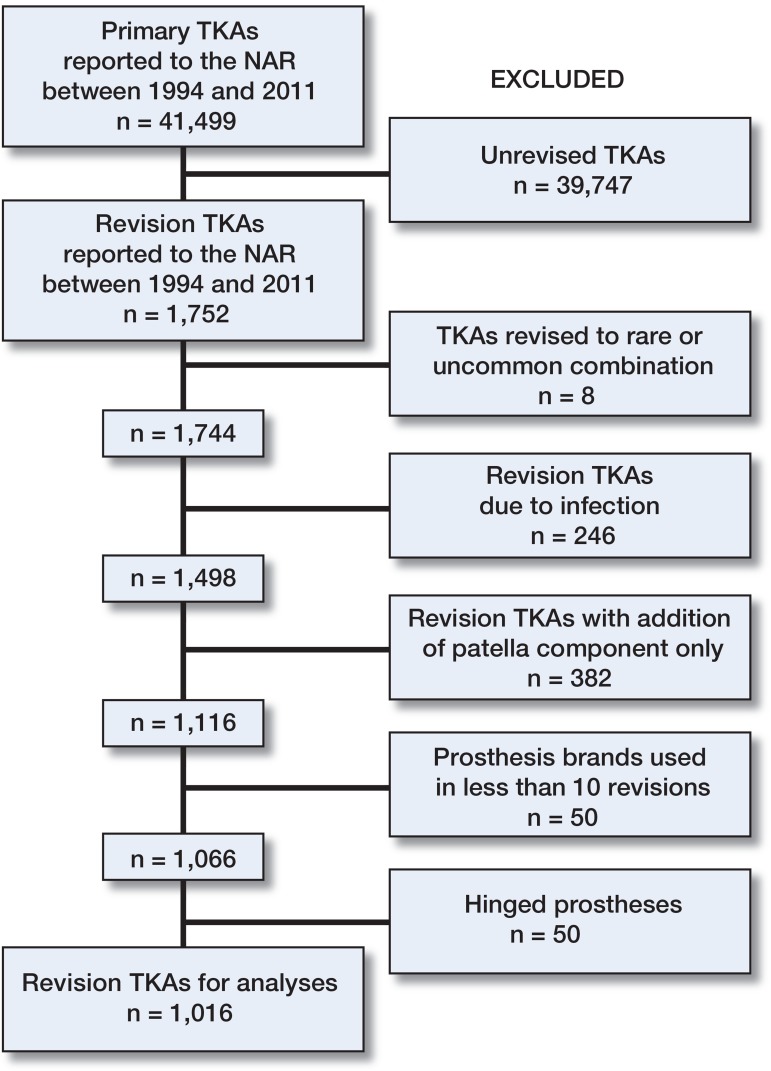

41,499 primary TKAs were reported to the NAR between January 1994 and December 2011. Of these, 1,752 TKAs (4.2%) had a revision operation. Only revision TKAs that had their corresponding primary TKAs recorded in the NAR were included in the study. TKAs revised to rare or uncommon prosthesis combinations (n = 8), revised due to infection (n = 246), revised only with the addition of a patellar component (n = 382), or revised to a hinged prosthesis (n = 50) were excluded, as were prosthesis brands that had been used in less than 10 revision TKAs (n = 50). Thus, 1,016 aseptic revision TKAs remained for analyses (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Description of study population for revision total knee arthroplasties (TKAs) (Norwegian Arthroplasty Register (NAR) 1994–2011).

The unique identification number assigned to each resident of Norway was used to link sequences of operations (Furnes et al. 2002, Lygre et al. 2011). Dates of emigration or death were obtained from the National Population Register (Lygre 2010) and the survival times of implants in these patients were censored at the date of emigration or death. Otherwise, the survival times were censored at the end of the study on December 31, 2011. Immediately after each operation, information on knee arthroplasties performed at any Norwegian hospital is routinely documented by the orthopedic surgeon on a standardized 1-page paper form and sent to the NAR. Information on each implant component, with catalog numbers supplied by the manufacturer, was obtained from the stickers and attached to the form by the operating surgeon (Furnes et al. 2002).

Operational definitions

In this study, “revision” was defined as the removal, addition, or exchange of part of an implant or the whole implant for the first time. “Re-revision” was defined as revision of revision TKAs. Re-revision of revision TKAs for any reason was the main outcome in the survival analysis. The reasons for revision and re-revision operations were arranged into 14 categories. The reason for revision or re-revision was evaluated and reported by the orthopedic surgeon. Multiple reasons could be reported for each case. Pain was only considered as a primary cause of revision or re-revision if no other cause was reported. Infection was considered as the primary cause of failure if combined with other causes of revision or re-revision. Whether the whole prosthesis or parts of the prosthesis were removed or exchanged at revision and re-revision were recorded. The types of revision operations were arranged into 6 categories (Table 2). To make the material more homogenous when we compared the types of revision operations, only exchange of the whole prosthesis, exchange of the femoral or tibial component, and exchange of the tibial liner were used in the Kaplan-Meier and Cox regression analyses.

Table 2.

Breakdown of types of revision operations: revision TKAs and re-revision TKAs. Values are percentages

| Type of operation | Revision | Re-revision |

|---|---|---|

| Exchange of femoral or tibial component | 31 | 14 |

| Exchange of the whole prosthesis | 37 | 36 |

| Exchange or insertion of patellar component | 4 | 3 |

| Exchange of tibial liner | 25 | 20 |

| Removal of part of prosthesis | 1 | 18 |

| Other, or incomplete information | 2 | 9 |

Statistics

Kaplan-Meier and Cox regression analyses were used to assess the survival rate and the relative risk of re-revision with all causes of re-revision as endpoint. The log-rank test was used to reveal statistically significant differences between groups in the Kaplan-Meier analyses. The median follow-up time was calculated using the reverse Kaplan-Meier method (Altman et al. 1995).

Survival analyses were undertaken separately for the different types of revision TKAs (revision total knee arthroplasty with resurfaced patella, or non-resurfaced patella) and the different prosthesis brands. Separate survival analyses were also done for type of revision operation (exchange of the whole prosthesis, exchange of the femoral or tibial component, or exchange of the tibial liner), use of bone impaction grafting (with or without), stems (with or without), posterior cruciate stabilization (PCS) (with or without), type of fixation (cemented, hybrid, or uncemented), and period of revision operation (1994–2002 or 2003–2011). The survival curves are given for survival times where more than 30 revision TKAs remained at risk of re-revision.

In observational studies, such as arthroplasty registry studies, there may be systematic differences between groups of patients with different types of prostheses, and these systematic differences may affect the validity of the results (Ranstam et al. 2011). To account for systematic imbalance in predictive factors between the patient groups with different types of prostheses and to increase the validity of the results, adjustment for covariates representing known or suspected confounders is essential. The Cox regression model is a statistical tool to explore the effect of 1 or more factors on survival (rate) and to adjust for potential confounding factors (Ranstam et al. 2011). Thus, in the Cox regression model we adjusted for the potential confounding factors that we know from the registry database: revision TKA with and without resurfacing of the patella, age (< 60, 60–70, > 70 years), sex, type of fixation, year of revision operation, type of revision operation, whether or not the primary or the revision TKA was resurfaced, and prosthesis brands. The selection of these adjustment variables was based upon our own hypotheses and previous findings from the literature.

The proportional hazard assumption of the Cox model was assessed by graphical examination and by goodness-of-fit test (Kleinbaum and Klein 2012). The goodness-of-fit test (which is based on Schoenfeld residuals) showed that the assumption was met for all variables included in the multiple Cox regression analyses. However, for the graphical examination it appeared that 2 variables (year of revision operation and type of revision TKA) violated this assumption. Thus, adjustment of relative re-revision risk ratios were performed by partitioning follow-up time into 2 intervals: 0–3 years and > 3 years (for year of revision operation) and 0–7 years and > 7 years (for type of revision TKA) using Cox regression analysis.

All p-values ≤ 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. The statistical analyses were performed using the IBM-SPSS software version 21.

Ethics and protection of personal information

All data files and results were processed and presented anonymously according to the guidelines in the license given to the NAR by the Norwegian Data Inspectorate (reference number: 03/00058-15/JTA and last issued April 19, 2012).

Results

Characteristics of revision TKAs

Demographic information and characteristics of revision TKAs are summarized in Tables 1–3. The median (range) age of all patients at the time of revision was 69 (25–94) years. Women were over-represented (68%). 86% of the revision TKAs were cemented with antibiotic-loaded cement. Exchange of the whole prosthesis (37%), exchange of the femoral or tibial component (31%), and exchange of the tibial liner (25%) were the most frequent types of revision operations performed. The Profix (n = 225) and the LCS Complete (n = 212) were the 2 most frequently used brands in Norway in terms of the number of revision TKA operations.

Table 1.

Demographic data for 1,016 revision TKAs reported to the NAR from January 1994 to December 2011. Values are percentages

| Age at revision |

Males | Type of fixation |

Stems a | Bone impaction b | PCS c | TKA–NRP d | Revised 2003–2011 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 60 | 60–70 | > 70 | Cemented e | Hybrid f | Uncemented | ||||||

| 25 | 28 | 47 | 32 | 86 | 13 | 1 | 42 | 18 | 30 | 73 | 78 |

a 30% of revision TKAs had missing information regarding stems.

b Registration of information about the use of bone impaction started in 2005. Thus, this is the percentage of those knees operated between 2005 and 2011.

c PCS: posterior cruciate stabilizing.

d TKA–NRP: revision total knee arthroplasty with non-resurfaced patella.

e Antibiotic-loaded bone cement was used in 99.9% of cemented prostheses.

f Some, but not all components (femoral, tibial, or patellar) were cemented.

Table 3.

Demographic data on prosthesis brands commonly used in revision TKA operations reported to the NAR from January 1994 through December 2011

| Brand of prosthesis | No. of prostheses | Age at revision |

No. of males | No. of hospitals a | No. of TKA–NRP b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 60 | 60–70 | > 70 | |||||

| Profix | 255 | 82 | 81 | 92 | 74 | 44 | 185 |

| LCS Complete c d | 212 | 41 | 70 | 101 | 72 | 33 | 196 |

| LCS c e | 150 | 23 | 43 | 84 | 38 | 29 | 110 |

| Genesis I f | 122 | 24 | 24 | 74 | 37 | 20 | 63 |

| NexGen | 79 | 28 | 20 | 31 | 26 | 26 | 48 |

| Duracon g | 74 | 26 | 21 | 27 | 31 | 13 | 61 |

| Vanguard h | 28 | 3 | 9 | 16 | 8 | 8 | 27 |

| Triathlon | 20 | 3 | 4 | 13 | 8 | 13 | 20 |

| AGC Anatomic j | 19 | 8 | 2 | 9 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

| Kinemax | 16 | 0 | 3 | 13 | 4 | 7 | 4 |

| AGC Universal | 16 | 7 | 3 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| Tricon II j | 15 | 7 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 11 | 5 |

| MAXIM k | 10 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 8 |

| Total | 1,016 | 255 | 284 | 477 | 323 | 66 l | 744 |

a Number of hospitals that had used each of these prosthesis brands for revision.

b Revision total knee arthroplasty with non-resurfaced patella.

c Mobile-bearing prosthesis brands.

d 42 LCS for femoral component, 2 LCS for intermediate component, 2 LCS, 1 Profix, and 1 LCS Universal for distal component were used in combination with LCS Complete for femoral component.

e 3 LCS Universal for distal component, 121 LCS Universal for intermediate component, 1 LCS Complete for intermediate component, and 2 LCS Complete for patellar component were used in combination with LCS.

f1 Tricon II for distal component, 1 Tricon II for intermediate component, and 1 Tricon-C with Pro-Fit for femoral component were used in combination with Genesis I.

g 1 KOTZ femoral and 1 KOTZ distal were used in combination with Duracon for other components.

h 1 AGC Universal for patellar component was used in combination with Vanguard for other component.

i 3 MAXIM for distal component and 4 MAXIM for intermediate component were used in combination with AGC Anatomic for femoral component.

j 12 Tricon-C with Pro-Fit for femoral component and 3 Tricon-M for femoral component were used in combination with Tricon II.

k 10 AGC Anatomic for femoral component and 3 AGC Anatomic for patellar component were used in combination with MAXIM for other components.

l Total number of hospitals that had reported revision TKA operations to the NAR between 1994 and 2011.

Mode of failure and time to failure of revision TKAs

Overall, 145 knees (14%) failed after revision TKA. Deep infection, instability, loose tibia, and pain alone were the 4 most frequent reasons for re-revision (Table 4). The mean (SD) time to failure of revision TKA was 4.6 (3.5) years and 89 knees (61%) failed within the first 2 years after revision. The mean time interval between revision and re-revision TKA varied with the mode of failure, and was 4.4 years for loose tibia, 2.7 years for pain alone, 2.2 years for instability, and 1.3 years for deep infection.

Table 4.

Reasons for revision and re-revision TKA operations reported to the NAR from January 1994 through December 2011

| Reason for revision | Revision a n (%) | Re-revision a n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Loose femur | 143 (14) | 13 (9) |

| Loose tibia | 398 (39) | 25 (17) |

| Loose patella | 15 (2) | 2 (1) |

| Dislocation of patella | 28 (3) | 6 (4) |

| Dislocation other than patella | 31 (3) | 6 (4) |

| Instability | 248 (24) | 37 (26) |

| Malalignment | 133 (13) | 10 (7) |

| Deep infection b | – | 41 (28) |

| Periprosthetic fracture | 58 (6) | 7 (5) |

| Defect/wear of polyethylene insert | 117 (12) | 6 (4) |

| Pain alone | 83 (8) | 15 (10) |

| Progression of arthritis | 3 (<1) | 1 (1) |

| Arthrofibrosis and stiff knee | 58 (6) | 4 (3) |

| Other, or incomplete information | 46 (5) | 3 (2) |

a More than one reason may have been reported.

b Excluded from analysis of revision TKAs (see Figure 1).

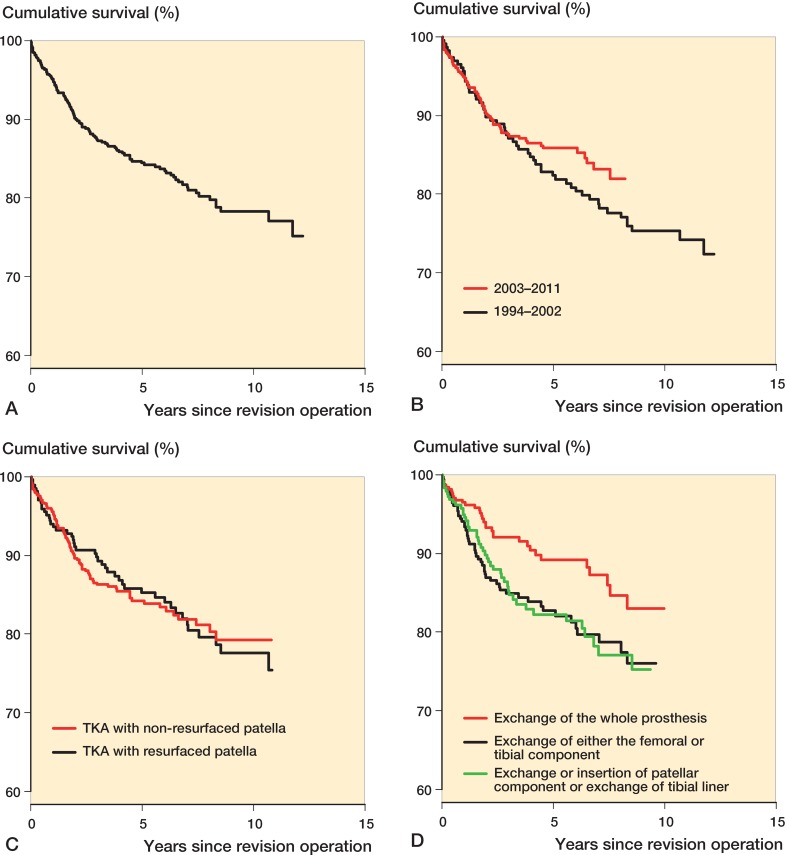

Type of revision TKA and year of revision operation

The cumulative survival rates of revision TKAs with all causes of re-revision as the endpoint were 85% at 5 years, 78% at 10 years, and 71% at 15 years (Figure 2A and Table 5). A higher percentage of re-revision was observed for revision TKAs with resurfaced patella (48 of 272 knees) than for revision TKAs with non-resurfaced patella (97 of 744 knees). However, there was no statistically significant difference in survival rates between TKAs with resurfaced and non-resurfaced patella (Figure 2C and Table 6). To check for time-dependent differences in results of revision, revison operations performed in the period 1994–2002 were compared to revisions performed in the period 2003–2011. Overall, we found no statistically significant effect of period of revision operation on the survivorship of revision TKAs (Figure 2B and Table 6). There was a tendency of better survival for knee arthroplasties revised in the period 2003–2011 with follow-up of over 3 years, but the difference was not statistically significant (RR = 1.8; p = 0.2).

Figure 2.

Survival curve (Kaplan-Meier) for revision TKAs: overall survival of prostheses (panel A), according to year of revision operations (B), according to type of revision TKA (C), and according to type of revision operation (D) with all causes of re-revision as the endpoint.

Table 5.

Kaplan-Meier estimated 5-, 10-, and 15-year survival percentage and median follow-up of revision TKAs with all cases of re-revision as the endpoint (NAR 1994–2011)

| No. of re-revisions /revisions | Median follow-up time in years (95% CI) | % Survival (95% CI) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-year | 10-year | 15-year | ||

| 145 / 1,016 | 4.5 (4.2–4.9) | 85 (82–87) | 78 (75–82) | 71 (62–80) |

Table 6.

Cox relative re-revision risk estimated with all cases of re-revision as the endpoint

| Variables | Re-revision / Revision (n) | RR (95%CI) |

p- value a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted b | |||

| Type of revision TKA | ||||

| With non-resurfaced patella | 97 / 744 | Ref. | Ref. | |

| With resurfaced patella | 48 / 272 | 1.0 (0.7–1.5) | 1.0 (0.7–1.5) | 1.0 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 78 / 693 | Ref. | Ref. | |

| Male | 67 / 323 | 2.2 (1.6–3.0) | 2.0 (1.4–2.8) | < 0.001 |

| Age at revision | ||||

| > 70 years | 51 / 477 | Ref. | Ref. | |

| 60–70 years | 43 / 284 | 1.4 (1.0–2.2) | 1.3 (0.8–2.0) | 0.2 |

| < 60 years | 51 / 255 | 1.8 (1.3–2.7) | 1.6 (1.1–2.5) | 0.03 |

| Type of fixation | ||||

| Cemented c | 128 / 870 | Ref. | Ref. | |

| Hybrid | 15 / 132 | 0.8 (0.5–1.3) | 0.7 (0.4–1.2) | 0.2 |

| Uncemented | 2 / 14 | 1.1 (0.3–4.5) | 1.0 (0.2–4.0) | 1.0 |

| Bone impaction d | ||||

| With | 4 / 113 | Ref. | ||

| Without | 54 / 481 | 3.6 (1.3–10.1) | d | 0.01 |

| Stems e | ||||

| With | 54 / 427 | Ref. | ||

| Without | 16 / 91 | 1.2 (0.7–2.0) | e | 0.6 |

| PCS f | ||||

| With | 45 / 310 | Ref. | ||

| Without | 100 / 706 | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) | f | 0.5 |

| Year of revision operation | ||||

| 2003–2011 | 90 / 787 | Ref. | Ref. | |

| 1994–2002 | 55 / 229 | 1.2 (0.9–1.8) | 1.2 (0.8–1.9) | 0.4 |

| Type of primary TKA | ||||

| With non-resurfaced patella | 113 / 813 | Ref. | Ref. | |

| With resurfaced patella | 32 / 203 | 0.8 (0.6–1.2) | 0.7 (0.5–1.2) | 0.2 |

| Exchange of | ||||

| the whole prosthesis | 35 / 380 | Ref. | Ref. | |

| femoral or tibial component | 54 / 313 | 1.7 (1.1–2.6) | 1.7 (1.1–2.6) | 0.02 |

| tibial liner | 43 / 253 | 1.8 (1.1–2.8) | 1.5 (0.9–2.3) | 0.1 |

a p-values for the last reported relative risk (RR).

b Adjusted for type of revision TKA, age at revision, sex, type of fixation, year of revision operation, type of primary TKA, type of revision operation, and prosthesis brand in the multiple Cox regression model.

c Antibiotic-containing cement was used in 99.9% of cemented prostheses.

d Registration of information on the use of bone impaction started in the NAR in 2005. Thus, bone impaction was excluded from the multiple Cox regression model, but sub-analysis was done for revision TKAs performed in 2005 and later. The risk of re-revision of TKAs without bone impaction was 3.2 (95% CI: 1.1–8.9; p = 0.03) compared to those with bone impaction. 52 knees had missing data regarding bone impaction.

e We did not adjust for stems due to the high percentage of missing data (30%).

fThe adjusted risk of re-revision of TKAs without PCS was 1.2 (95% CI: 0.8–1.7; p = 0.4) compared to those with PCS. Adjustment was made for type of revision TKA, age at revision, sex, type of fixation, year of revision operation, type of primary TKA, and prosthesis brand in the multiple Cox regression model.

g Due to the small group size, and to achieve more homogeneity, prostheses with type of revision operation other than exchange of the whole prosthesis, exchange of the femoral or tibial component alone, and exchange of the tibial liner were excluded from the Cox regression analyses.

Age and sex

The relative risk of failure of revision TKAs in patients less than 60 years of age was 1.6 times higher than in patients more than 70 years of age (p = 0.03). Male sex was a risk factor for re-revision (RR = 2.0; p <0.001) (Table 6).

Type of revision operation

Revisions done with exchange of either the femoral component or the tibial component had a 1.7 times higher risk of re-revision than complete revisions (p = 0.02). The exchange of a tibial liner tended to have a higher risk of re-revision than complete revision (RR = 1.5; p = 0.1) (Figure 2D and Table 6).

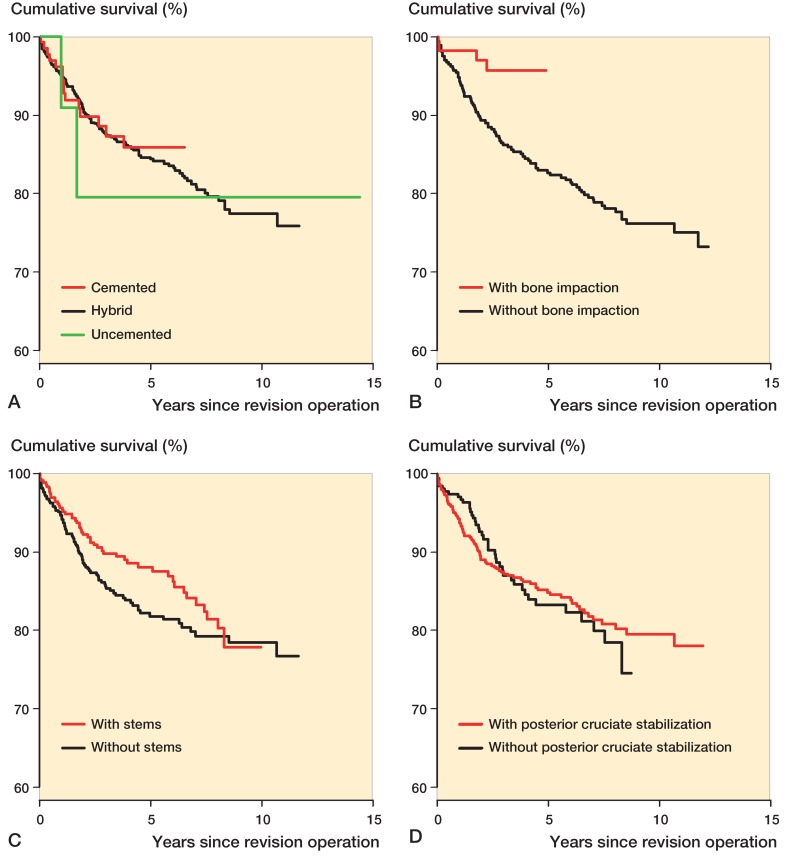

Type of fixation, bone impaction, stems, and PCS

There were no significant differences in survival rate between cemented, hybrid, and uncemented fixation (Figure 3 and Table 6). The NAR started registration of information about bone grafting in 2005. Thus, the analysis regarding the effect of bone impaction was limited to revision prostheses reported to the NAR between 2005 and 2011. Revisions without bone impaction had a 3.2-times higher risk of re-revision than those with bone impaction (p = 0.03) (Table 6). Unadjusted Cox regression analysis showed that the use of long stems did not have a significant influence on survival rate; nor did PCS (Figure 3 and Table 6). A high proportion of revision TKAs had missing information regarding use of stems (30%). Thus, the variable “use of stems” was excluded from the Cox regression analysis.

Figure 3.

Survival curve (Kaplan-Meier) for revision TKAs according to type of fixation (panel A), bone impaction (B), stem (C), and posterior cruciate stabilization (D). Registration of information about the use of bone impaction started in 2005. Thus, survival analysis according to bone impaction was done only for revision TKA operations reported to the NAR in 2005 and later.

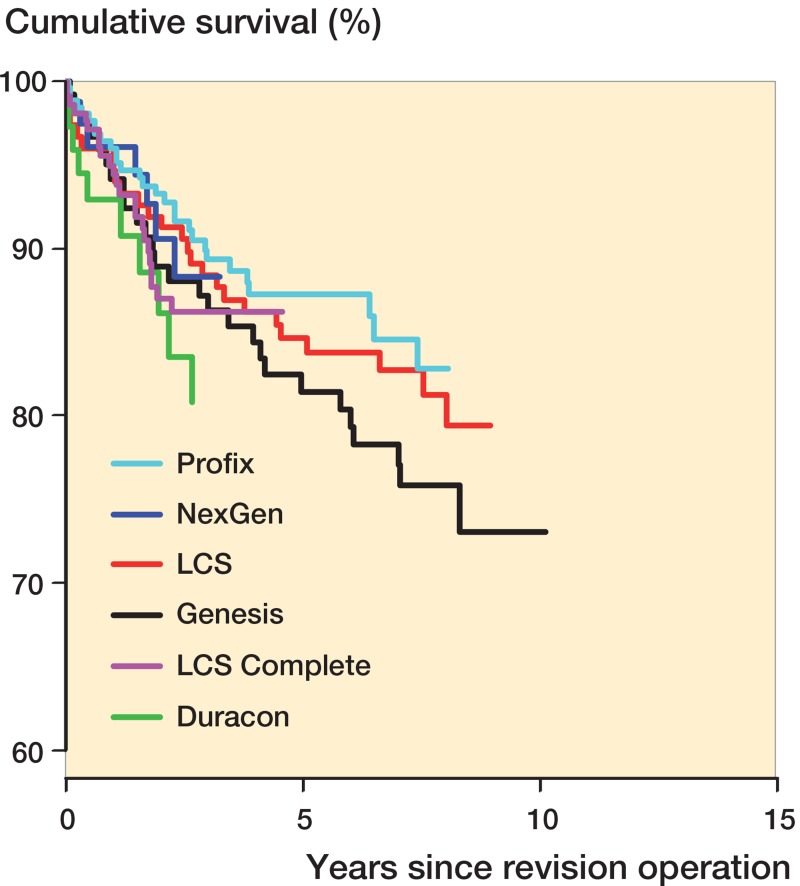

Brand of prosthesis

Separate analyses were performed for prosthesis brands used in ≥ 50 revisions. The 5- and 10-year survival rates were 81–88% and 73–83%. No statistically significant differences in survival rate or risk of re-revision were identified among the prosthesis brands (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Survival curve (Kaplan-Meier) according to the brand of revision prosthesis reported to the NAR 1994–2011 (n ≥ 50).

Discussion

Summary

Overall, the cumulative survival rate of non-infected revision TKA operations was 78% at 10 years. The survival rates for patella-resurfaced and non-resurfaced revision TKAs were similar. Better survival rate was observed with complete revisions than for partial ones in which only one component was revised. Young age and male sex were risk factors for re-revision. Deep infection, instability, loose tibial component, and pain alone were the most frequently observed causes of re-revision. Survival rates were similar among prosthesis brands.

Explanations/mechanisms and comparison with other relevant studies

As reported in previous studies, the survival rate for revision knee arthroplasty at 10 years has ranged from 52% to 97% (Whaley et al. 2003, Sierra et al. 2004, Sheng et al. 2006, Suarez et al. 2008, Wood et al. 2009, Mortazavi et al. 2011, Bae et al. 2013, AOANJRR 2013). However, in these studies there were differences in revision techniques, patient profiles, prosthesis design, definition of “failure”, and length of follow-up, which make direct comparison difficult. Mortazavi et al. (2011) reported a survival rate of revision TKAs of 78% at 8 years due to aseptic failure; however, the survival rate dropped to 73% when all causes of revision were included. Using re-revision as endpoint, a study from the Finnish Arthroplasty Register found that the survival rate of revision TKAs was 89% at 5 years and 79% at 10 years (Sheng et al. 2006). Sierra et al. (2004) found a re-revision rate of 16%, 26%, and 34% at 5, 10, and 15 years. In Australia, the cumulative percentage of re-revision of TKAs was 13%, 16%, and 22% at 3, 5, and 10 years (AOANJRR 2013), which is in accordance with our findings.

Use of patella component

The rate of re-revision was higher in revision TKAs with resurfaced patella (48 of 272 knees) than in those with non-resurfaced patella (97 of 744 knees). However, we found no statistically significant differences in the risk of re-revision between TKA with resurfaced patella and TKA with non-resurfaced patella. To our knowledge, there have been no previous comparative studies on patella-resurfaced and non-resurfaced revision TKAs. Clements et al. (2010) reported a statistically significantly lower revision rate in patients who had undergone patella resur¬facing in primary TKA than in those with a non-resurfaced patella. The explanation given for the difference was that TKAs with non-resurfaced patella were more likely to be revised due to patellofemoral pain, and more likely to be revised with patella addition. Moreover, sur¬geons may prefer to revise a painful non-resurfaced knee arthroplasty by secondary patella addition than to revise a painful patella-resurfaced TKA (Lygre et al. 2011). We could not find the same tendency in revision TKA. There could be several reasons for this finding, including length of follow-up, patient comorbidities, the degree of bone defects and instability, and surgeon’s skill and volume.

Type of revision operation

We found that partial revisions had a higher risk of re-revision than complete revisions, which is consistent with the results of previous studies (Engh et al. 2000, Babis et al. 2002, Leopold et al. 2003, Mackay and Siddique 2003, Suarez et al. 2008). As reported by Mackay and Siddique (2003), patients treated with tibial tray revision and retention of the femoral component had a higher rate of re-revision (28%) than patients treated with revision of both components (7%). Others have found high failure rates after isolated revision of the tibial insert (Engh et al. 2000, Babis et al. 2002). In their review, Riaz and Umar (2006) concluded that selective revision is usually not a good treatment option. Possible explanations for such a high rate of failure following partial revision TKAs as compared to complete revision in our study could be higher polyethylene wear, residual malalignment, and/or residual instability following partial revisions. Mackay and Siddique (2003) argued that the loose tibial component can have generated particulate debris even though the femoral component is not radiologically loose, and such a problem may only be adequately eliminated after removal of both components. The failure of revision TKA is often multifactorial. The surgeon’s decision about whether to perform a partial or a complete revision might be influenced by patient-related, implant-related, and/or technical factors. Our findings suggest that even when a clinically and radiologically intact component is found during surgery, revision of both components of the prosthesis may be recommendable.

Mode of failure

We found that deep infection was the most frequent cause of failure of revision TKAs (28%). Although this is a rather high percentage, it is lower than what was reported in other studies (Suarez et al. 2008, Mortazavi et al. 2011, Bae et al. 2013). In the present study, only revisions done for reasons other than infection were included. Thus, we believe that very few of the knees were infected before revision. This was not the case in the other studies, and the higher percentage of re-revision due to infection is therefore not surprising. The poorly vascularized tissue often encountered after multiple operations, the longer operative time for revision surgery, previous wounds, larger implants, comorbidity, and the increasing average age of the patient population may increase the risk of infection (Hanssen and Rand 1999, Garvin and Cordero 2008, Bae et al. 2013).

Age and sex

We found that younger age (< 60 years) was a risk factor for re-revision. This can possibly be attributed to the greater activity levels in younger patients or to the surgeon’s reluctance to re-revise older patients due to medical comorbidities. Our finding agrees with the findings of other authors (Sheng et al. 2006, Mabry et al. 2007, Suarez et al. 2008). However, Ong et al. (2010) found no association between age and risk of re-revision.

Male patients had double the risk of re-revision. A study from the Finnish Arthroplasty Register found a tendency of lower risk of re-revision in females than in males (Sheng et al. 2006). A previous study on primary hip arthroplasty from our registry also found a higher risk of revision due to infection in males (Dale et al. 2011, 2012). This gender-related difference could be caused by lower body weight in women—and a lower intensity of use of the prosthetic joint (Sheng et al. 2006). Other authors have not found gender-related differences (Mabry et al. 2007, Bae et al. 2013). This disagreement may be attributable to smaller sample sizes (Mabry et al. 2007, Bae et al. 2013) or to the proportion of female study participants (178 females and 18 males) (Bae et al. 2013).

Fixation technique and year of revision operation

In the present study, the type of fixation and the use of PCS had no statistically significant effect on the survival rates of revision TKAs. On the other hand, a study from the Finnish Arthroplasty Register found that cemented prostheses had better survival rates than hybrid and uncemented prostheses. However, the authors were not able to verify this result with Cox regression analysis, due to a high percentage of missing information (57%) (Sheng et al. 2006). In their comparative study, Cintra et al. (2011) concluded that there were no differences in survival rate between cemented and uncemented prostheses. In the present study, we had few patients in the uncemented and hybrid group, and the lack of differences could be attributed to the low statistical power.

Impaction bone grafting is one of the various techniques used to treat bone loss in revision joint arthroplasty (Toms et al. 2004, Lotke et al. 2006). In the present study, the risk of re-revision after revision TKA without bone impaction was higher than after bone impaction. We did not have information on the degree of bone loss, so the result must be interpreted with caution. Furthermore, the technique used—and whether the impaction involved the periarticular bone or the meth-/diaphysis—is not known for the individual case. In their study of 48 revision TKAs treated with impaction grafting, Lotke et al. (2006) reported that there were no mechanical failures of the impaction grafted components at an average follow-up of 3.6 years, but they found a rather high overall rate of complications (14%). Their conclusion was that impaction grafting had excellent durability and versatility in bone loss in revision TKAs.

In revision TKA, the main purpose of an intramedullary stem extension is to offload and reduce interfacial stress of damaged periarticular bone in the distal femur or proximal tibia by providing additional prosthetic surface area for implant fixation (Mabry and Hanssen 2007). Nazarian et al. (2002) did not find any differences between stemmed and unstemmed revision knee arthroplasty. In our crude analysis, we found that there was no statistically significant difference in risk of re-revision between stemmed and unstemmed revision TKAs. However, the tibial and femoral stems were not entered in the database at the catalog number level, and sample tests comparing the database and the paper forms filled in by the surgeons revealed 30% underreporting of stem use in the database, so an adjusted analysis of the effect of stem use was not considered appropriate. The result must therefore be interpreted with caution.

Advances in implant design, and in surgical and fixation techniques, may have improved the survival of knee arthroplasties over time. In the present study, however, we found similar risks of re-revision for revision TKA operations performed in the year 2002 or before and for those performed in the year 2003 or later. In other words, there was no improvement in the survival of revision TKAs over the study period. 66 hospitals had done the revision operations. Further studies should be done to investigate whether revision procedures should be done at fewer institutions. We already know that high-volume hospitals have fewer revisions in primary TKA (Badawy et al. 2013).

Prosthesis brands

To our knowledge, there have been no previous studies assessing the influence of prosthesis brand on the survival rate of revision TKAs. We found similar risks of re-revision for the most commonly used prosthesis brands. However, the number of cases operated with each brand was limited and the results should be interpreted with caution.

Strengths and limitations

The strength of the present study was that it was based on data from a nationwide registry, thus combining results from low- and high-volume centers, and from highly specialized and general orthopedic surgeons. Thus, the external validity of our findings may be higher than findings from studies with a randomized design. The registration completeness of the NAR data (both primary and revision knee procedures) is excellent (Espehaug et al. 2006). To our knowledge, there has been no previous comparison of the outcome of resurfaced and non-resurfaced revision TKAs.

Our study also had some limitations. It was an observational study. A randomized controlled trial (RCT) is the best method of comparing treatment modalities. However, it is uncommon to study rare incidences such as those of revision and especially re-revision joint replacements in RCTs, for economic and practical reasons (Benson and Hartz 2000, Lygre et al. 2011). Thus, large observational studies linked to arthroplasty registries are the main source of knowledge on these subjects. Different forms of bias may affect observational studies. In the present study, we adjusted for the confounding factors that are available in the registry database, but there are several factors that were not taken into consideration. These factors include patient comorbidities, the degree of bone defects and instability, and surgeon’s skill and volume. Revision TKA is a bespoke operation; each one is different, and surgeons have to tailor their approach to surgery depending on the problems each individual case presents. So confounding by indication might influence the results, and these must be interpreted with this in mind. Furthermore, failure was defined as implant revision, which is a crude measure; radiological and clinical failures that were not revised in the study period were not registered. We did not perform adjustments for bilaterality in our analyses. However, no bias would be expected from ignoring the effect of bilateral prostheses (Robertsson and Ranstam 2003). We did not perform a post hoc power analysis to verify whether or not the study had adequate power, but we report confidence intervals. Levine and Ensom (2001) reported that confidence intervals give sufficient information information regarding power to detect the observed effect.

Further research

We have assessed the re-revision rates of revision TKAs. However, not all patients with clinical failure will be offered a second or third revision procedure. This can be due to factors related to the patient, the surgeon, and the available resources. Also, the results in terms of pain relief and function are uncertain after repeated surgery. On the other hand, complications are increasingly common as the number of procedures done on an individual patient increases. Thus, surgeons will be reluctant to advise patients to undergo re-revisions unless it is absolutely necessary. Furthermore, survival analysis of revision TKA tells us nothing about those patients who did not undergo re-revision (Robertsson 2000). The NAR has no information on patient satisfaction, pain, and function after revision knee operations. A further study is needed to assess the functional outcome, pain relief, and patient satisfaction with revision prostheses.

Conclusion

Complete TKA revisions had better survival than partial revisions. Thus, partial revisions should only be done after careful consideration in specific instances. Male sex and younger age were risk factors for re-revision. Patellar resurfacing, the use of posterior stabilization, and type of fixation had no effect on the survival of revision TKAs. Deep infection and instability were the most frequent causes of failure of revision TKAs.

Acknowledgments

THL and SHLL: study design, statistical analysis, interpretation of the study findings, and drafting of manuscript. OF: study design and medical supervision, interpretation of the study findings, and drafting of manuscript. AS and GH: interpretation of the study findings and drafting of manuscript. All the authors read, edited, and approved the final manuscript.

We are very grateful to the NAR for allowing us access to the registry dataset. Our thanks also go to all the Norwegian orthopedic surgeons in 66 hospitals for reporting their surgical cases to the NAR. We also thank all the patients who gave their consent to be entered into the NAR database, on which this article was based.

The Norwegian Arthroplasty Register is financed by the Western Norway Regional Health Authority (Helse-Vest). During this study, THL received a study grant from the Health Research Program at Haukeland University Hospital.

No competing interests declared.

References

- Altman DG, De Stavola BL, Love SB, Stepniewska KA. Review of survival analyses published in cancer journals . Br J Cancer. 1995;72(2):511–8. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AOANJRR. Revision of Hip & Knee Arthroplasty : Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry (AOANJRR), Supplementary Report https://aoanjrr.dmac.adelaide.edu.au/documents/10180/127369/Revision%20of%20Hip%20%26%20Knee%20Arthroplasty. 2013

- Babis GC, Trousdale RT, Morrey BF. The effectiveness of isolated tibial insert exchange in revision total knee arthroplasty . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2002;84(1):64–8. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200201000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badawy M, Espehaug B, Indrekvam K, Engesaeter LB, Havelin LI, Furnes O. Influence of hospital volume on revision rate after total knee arthroplasty with cement . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2013;95(18):e131. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.00943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae DK, Song SJ, Heo DB, Lee SH, Song WJ. Long-term Survival Rate of Implants and Modes of Failure After Revision Total Knee Arthroplasty by a Single Surgeon . J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(7):1130–4. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2012.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann J, Luring C, Springorum R, Kock FX, Grifka J, Tingart M. Fixation of revision TKA: a review of the literature . Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19(6):872–9. doi: 10.1007/s00167-010-1249-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson K, Hartz AJ. A comparison of observational studies and randomized, controlled trials . N Engl J Med. 2000;342(25):1878–86. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006223422506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr AJ, Robertsson O, Graves S, Price AJ, Arden NK, Judge A, et al. Knee replacement . Lancet. 2012;379(9823):1331–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60752-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cintra FF, Yepéz AK, Rasga M GS, Abagge M, Alencar p GC. Tibial component in revision of total knee arthroplasty: Comparison between cemented and hybrid fixation. Rev Bras Ortop. 2011;46(5):585–90. doi: 10.1016/S2255-4971(15)30416-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements WJ, Miller L, Whitehouse SL, Graves SE, Ryan P, Crawford RW. Early outcomes of patella resurfacing in total knee arthroplasty . Acta Orthop. 2010;81(1):108–13. doi: 10.3109/17453670903413145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale H, Skramm I, Lower HL, Eriksen HM, Espehaug B, Furnes O, et al. Infection after primary hip arthroplasty: a comparison of 3 Norwegian health registers . Acta Orthop. 2011;82(6):646–54. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2011.636671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale H, Fenstad AM, Hallan G, Havelin LI, Furnes O, Overgaard S, et al. Increasing risk of prosthetic joint infection after total hip arthroplasty . Acta Orthop. 2012;83(5):449–58. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2012.733918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engh GA, Koralewicz LM, Pereles TR. Clinical results of modular polyethylene insert exchange with retention of total knee arthroplasty components . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2000;82(4):516–23. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200004000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espehaug B, Furnes O, Havelin LI, Engesaeter LB, Vollset SE, Kindseth O. Registration completeness in the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register . Acta Orthop. 2006;77(1):49–56. doi: 10.1080/17453670610045696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehring TK, Odum S, Olekson C, Griffin WL, Mason JB, McCoy TH. Stem fixation in revision total knee arthroplasty: a comparative analysis . Clin Orthop. 2003;416:217–24. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000093032.56370.4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furnes O, Espehaug B, Lie SA, Vollset SE, Engesaeter LB, Havelin LI. Early failures among 7,174 primary total knee replacements: a follow-up study from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register 1994-2000 . Acta Orthop Scand. 2002;73(2):117–29. doi: 10.1080/000164702753671678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furnes O, Espehaug B, Lie SA, Vollset SE, Engesaeter LB, Havelin LI. Failure mechanisms after unicompartmental and tricompartmental primary knee replacement with cement . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2007;89(3):519–25. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furnes O, Baste V, Sørås TE, Krukhaug Y. The Norwegian Arthroplasty Register (NAR). Annual Report. http://nrlweb.ihelse.net/Rapporter/Rapport2012.pdf. 2012

- Garvin KL, Cordero GX. Infected total knee arthroplasty: diagnosis and treatment . Instr Course Lect. 2008;57:305–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gothesen O, Espehaug B, Havelin L, Petursson G, Lygre S, Ellison P, et al. Survival rates and causes of revision in cemented primary total knee replacement: a report from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register 1994-2009 . Bone Joint J. 2013;95-B(5):636–42. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.95B5.30271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greidanus NV, Peterson RC, Masri BA, Garbuz DS. Quality of life outcomes in revision versus primary total knee arthroplasty . J Arthroplasty. 2011;26(4):615–20. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2010.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanssen AD, Rand JA. Evaluation and treatment of infection at the site of a total hip or knee arthroplasty . Instr Course Lect. 1999;48:111–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havelin LI, Engesaeter LB, Espehaug B, Furnes O, Lie SA, Vollset SE. The Norwegian Arthroplasty Register: 11 years and 73,000 arthroplasties . Acta Orthop Scand. 2000;71(4):337–53. doi: 10.1080/000164700317393321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang SC, Kong JY, Nam DC, Kim DH, Park HB, Jeong ST, et al. Revision total knee arthroplasty with a cemented posterior stabilized, condylar constrained or fully constrained prosthesis: a minimum 2-year follow-up analysis . Clin Orthop Surg. 2010;2(2):112–20. doi: 10.4055/cios.2010.2.2.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinbaum DG, Klein M. New York: 2012. Survival analysis: a self-learning text. [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz SM, Ong KL, Schmier J, Mowat F, Saleh K, Dybvik E, et al. Future clinical and economic impact of revision total hip and knee arthroplasty . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) (Suppl 3) 2007;89:144–51. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leopold SS, Silverton CD, Barden RM, Rosenberg AG. Isolated revision of the patellar component in total knee arthroplasty . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2003;85(1):41–7. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200301000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine M, Ensom MH. Post hoc power analysis: an idea whose time has passed? . Pharmacotherapy. 2001;21(4):405–9. doi: 10.1592/phco.21.5.405.34503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotke PA, Carolan GF, Puri N. Impaction grafting for bone defects in revision total knee arthroplasty . Clin Orthop. 2006;446:99–103. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000214414.06464.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lygre SHL. Pain, function and risk of revision after primary knee arthroplasty (PhD Thesis) 2010.

- Lygre SH, Espehaug B, Havelin LI, Furnes O, Vollset SE. Pain and function in patients after primary unicompartmental and total knee arthroplasty . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2010a;92(18):2890–7. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.00917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lygre SH, Espehaug B, Havelin LI, Vollset SE, Furnes O. Does patella resurfacing really matter? Pain and function in 972 patients after primary total knee arthroplasty . Acta Orthop. 2010b;81(1):99–107. doi: 10.3109/17453671003587069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lygre SH, Espehaug B, Havelin LI, Vollset SE, Furnes O. Failure of total knee arthroplasty with or without patella resurfacing . Acta Orthop. 2011;82(3):282–92. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2011.570672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mabry TM, Hanssen AD. The role of stems and augments for bone loss in revision knee arthroplasty . J Arthroplasty (Suppl 1) 2007;22(4):56–60. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mabry TM, Vessely MB, Schleck CD, Harmsen WS, Berry DJ. Revision total knee arthroplasty with modular cemented stems: long-term follow-up . J Arthroplasty (Suppl 2) 2007;22(6):100–5. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackay DC, Siddique MS. The results of revision knee arthroplasty with and without retention of secure cemented femoral components . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2003;85(4):517–20. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.85b4.13749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masri BA, Meek RM, Greidanus NV, Garbuz DS. Effect of retaining a patellar prosthesis on pain, functional, and satisfaction outcomes after revision total knee arthroplasty . J Arthroplasty. 2006;21(8):1169–74. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2006.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortazavi SM, Molligan J, Austin MS, Purtill JJ, Hozack WJ, Parvizi J. Failure following revision total knee arthroplasty: infection is the major cause . Int Orthop. 2011;35(8):1157–64. doi: 10.1007/s00264-010-1134-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazarian DG, Mehta S, Booth RE., Jr A comparison of stemmed and unstemmed components in revision knee arthroplasty . Clin Orthop. 2002;404:256–62. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200211000-00039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong KL, Lau E, Suggs J, Kurtz SM, Manley MT. Risk of subsequent revision after primary and revision total joint arthroplasty. Clin Orthop. 2010;468(11):3070–6. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1399-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil N, Lee K, Huddleston JI, Harris AH, Goodman SB. Patellar management in revision total knee arthroplasty: is patellar resurfacing a better option? . J Arthroplasty. 2010;25(4):589–93. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranstam J, Karrholm J, Pulkkinen P, Makela K, Espehaug B, Pedersen AB, et al. Statistical analysis of arthroplasty data. I. Introduction and background . Acta Orthop. 2011;82(3):253–7. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2011.588862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riaz S, Umar M. Revision knee arthroplasty . J Pak Med Assoc. 2006;56(10):456–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertsson O. Lund, Sweden: 2000. The Swedisk Knee Arthroplasty Register Validity and Outcome (PhD Thesis) [Google Scholar]

- Robertsson O, Ranstam J. No bias of ignored bilaterality when analysing the revision risk of knee prostheses: analysis of a population based sample of 44,590 patients with 55,298 knee prostheses from the national Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register . BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2003;4:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertsson O, Bizjajeva S, Fenstad AM, Furnes O, Lidgren L, Mehnert F, et al. Knee arthroplasty in Denmark, Norway and Sweden . Acta Orthop. 2010;81(1):82–9. doi: 10.3109/17453671003685442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng PY, Konttinen L, Lehto M, Ogino D, Jamsen E, Nevalainen J, et al. Revision total knee arthroplasty Revision total knee arthroplasty: 1990 through 2002. A review of the Finnish arthroplasty registry . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2006;88(7):1425–30. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierra RJ, Cooney W P t, Pagnano MW, Trousdale RT, Rand JA. Reoperations after 3200 revision TKAs: rates, etiology, and lessons learned . Clin Orthop. 2004;425:200–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez J, Griffin W, Springer B, Fehring T, Mason JB, Odum S. Why do revision knee arthroplasties fail? . J Arthroplasty (Suppl 1) 2008;23(6):99–103. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg M, Lidgren L, W-Dahl A, Robertsson O. The Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register (SKAR). Annual Report. http://www.knee.nko.se/english/online/uploadedFiles/117_SKAR_2012_Engl_1.0.pdf. 2012 doi: 10.1302/2046-3758.37.2000289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Toms AD, Barker RL, Jones RS, Kuiper JH. Impaction bone-grafting in revision joint replacement surgery . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2004;86(9):2050–60. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200409000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whaley AL, Trousdale RT, Rand JA, Hanssen AD. Cemented long-stem revision total knee arthroplasty . J Arthroplasty. 2003;18(5):592–9. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(03)00200-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside LA. Cementless fixation in revision total knee arthroplasty . Clin Orthop. 2006;446:140–8. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000218724.29344.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood GC, Naudie DD, MacDonald SJ, McCalden RW, Bourne RB. Results of press-fit stems in revision knee arthroplasties . Clin Orthop. 2009;467(3):810–7. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0621-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]