Abstract

Background and purpose

Non-traumatic osteonecrosis is a progressive disease with multiple etiologies. It affects younger individuals more and more, often leading to total hip arthroplasty. We investigated whether there is a correlation between inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression and osteocyte apoptosis in non-traumatic osteonecrosis.

Patients and methods

We collected and studied 20 human idiopathic, non-traumatic osteonecrosis femoral heads. Subchondral bone samples in the non-sclerotic region (n = 30), collected from osteoarthritis patients, were used as controls. Spontaneously hypertensive rats were used as a model for osteonecrosis in the study. We used scanning electron microscopy, TUNEL assay, and immunohistochemical staining to study osteocyte changes and apoptosis.

Results

The morphology of osteocytes in the areas close to the necrotic region changed and the number of apoptotic osteocytes increased in comparison with the same region in control groups. The expression of iNOS and cytochrome C in osteocytes increased while Bax expression was not detectable in osteonecrosis samples. Using spontaneously hypertensive rats, we found a positive correlation between iNOS expression and osteocyte apoptosis in the osteonecrotic region. iNOS inhibitor (aminoguanidine) added to the drinking water for 5 weeks reduced the production of iNOS and osteonecrosis compared to a control group without aminoguanidine.

Interpretation

Our findings show that increased iNOS expression can lead to osteocyte apopotosis in idiopathic, non-traumatic osteonecrosis and that an iNOS inhibitor may prevent the progression of the disease.

Patients with non-traumatic osteonecrosis (ON) fall into 2 groups: those with apparent etiological or risk factors and those without any identifiable etiology (Malizos et al. 2007). There are several hypotheses about the pathogenesis of so-called idiopathic ON, such as marrow edema and hemorrhage, thrombi or emboli in the microvasculature, cytotoxicity, lipocyte hyperplasia, osteoblast and osteoclast coupling dysfunction, and most recently, osteocyte apoptosis (Zalavras et al. 2000, Assouline-Dayan et al. 2002, Youm et al. 2010). It has also been reported that alterations in glucose and lactate levels in synovial fluid are associated with ON of the femoral head, indicating that synovial fluid metabolites may be an effective method of monitoring the disease progression (Huffman et al. 2007).

Osteocytes have many functions, and they act as an orchestrator in bone remodeling (Bonewald 2011). Recently, it has been reported that the incidence of osteocyte apoptosis is increased in the femoral head during ON, regardless of etiological factors (Mutijima et al. 2014). However, the detailed apoptosis pathways and potential regulators in the pathogenesis of osteocytic apoptosis are not fully understood in non-traumatic osteonecrosis.

Apoptosis pathways can be initiated through either the receptor pathway (the exogenous signal pathway) at the plasma membrane by death receptor ligation or the mitochondrial pathway (the endogenous signal pathway) (Elmore 2007). In the exogenous signal pathway, stimulation of death receptors of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor superfamily results in receptor aggregation and recruitment of the adaptor molecule Fas-associated death domain (FADD) and caspase-8. Upon recruitment, caspase-8 becomes activated and initiates apoptosis by direct cleavage of downstream effector caspases. In the endogenous signal pathway, a stress signal is initiated through the binding of activated Bax to the outer membrane of mitochondria—to induce the release of apoptogenic factors such as cytochrome C into the cytoplasm. The release of cytochrome C into the cytosol triggers activation of caspase-3, leading to apoptosis.

Nitric oxide (NO) has been identified to be an agent that could induce non-traumatic osteonecrosis (Calder et al. 2004, Pan et al. 2013). NO is a small molecule produced by the enzymatic action of NO synthase. There are 3 protein forms of nitric oxide synthase (NOS): neuronal NOS, endothelial NOS (eNOS), and inducible NOS (iNOS). Neuronal NOS and eNOS usually exist as constitutive forms to maintain physiological effects, while iNOS is produced in response to stimulation (Li and Poulos 2005). A number of drugs can regulate the activities of NOS, and aminoguanidine (AMG) has been reported to be an inhibitor of NOS—mainly acting on iNOS (Suzuki et al. 1996). To our knowledge, AMG has not been investigated in non-traumatic osteonecrosis treatment. We investigated possible correlations between iNOS expression and osteocyte apoptosis and also the therapeutic effect of AMG in non-traumatic osteonecrosis.

Patients and methods

Human bone samples

The study was approved by the human ethics committee of the Second Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, China. 20 femoral heads were collected from 20 patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty (THA) because of non-traumatic idiopathic osteonecrosis of the femoral head. The average age of the patients was 62 years (range 39–73). None of them had any evidence of tumors, tuberculosis, or metabolic bone disease. Conventional radiographs and computed tomography showed stage III or IV according to the Ficat classification in all patients. The areas of osteonecrosis in femoral heads (in the ON group) were cut into pieces (1 × 1 × 1 cm3) immediately after they were collected; half of the specimens were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for histology and the other half were rinsed in 0.1 mol/L sodium cacodylate buffer (Sigma-Aldrich) and fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich) in the same buffer containing 0.05% tannic acid (Sigma-Aldrich), for scanning electron microscopy (SEM). As in a previous study (Samara et al. 2013), the relatively healthy bone was collected as control from the healthy region of the femoral headneck about 1 cm away from the zone of osteonecrosis in each patient (Figure 1b) (in the no-ON group). The subchondral bone samples in the non-sclerotic region (n = 30) collected from osteoarthritis patients due to hip replacement surgery with a Mankin score of less than 3 (the OA group) were used as OA controls (Mankin et al. 1971).

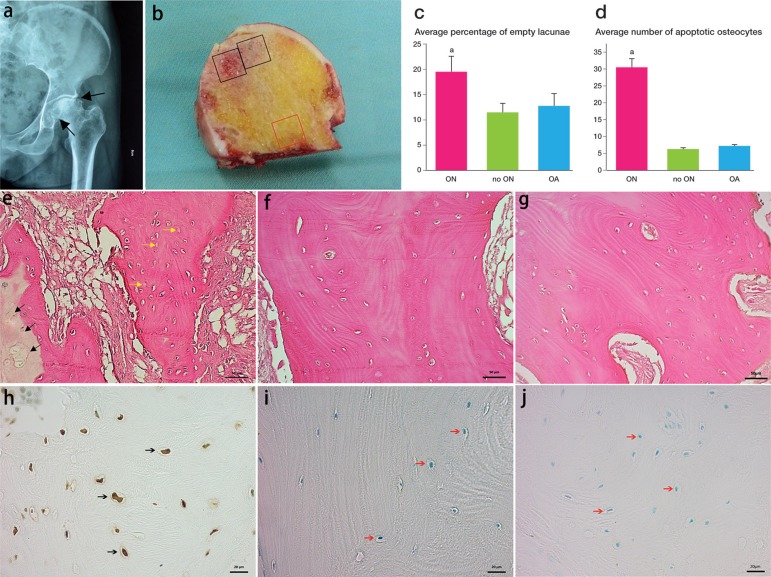

Figure 1.

Representative radiographs and histology of human femoral head osteonecrosis. Radiograph showed typical osteonecrosis in the femoral head (panel a). The femoral head had obvious subchondral bone tissue collapse. In panel b, the black squares show the region of necrotic tissue (ON group) and the red square shows normal bone (no-ON group). Hematoxylin and eosin staining showed the general histological appearance of osteonecrosis (panel e; black arrow: osteonecrosis; yellow arrow: empty lacunae) and healthy bone (panels f and g). Panel c shows the difference in average percentage of empty lacunae in the osteonecrosis group and the control groups. Representative TUNEL-stained sections showed more osteocytes undergoing apoptosis in the osteonecrosis group (panel h) than in the control groups (panels i and j). The average number of apoptotic osteocytes was higher in the osteonecrosis group (panel d). ap < 0.001 (in panels c and d).

Scanning electron microscopy of human specimens

After the specimens were fixed overnight in the solution mentioned above, the samples were washed 3 times over a 24-h period with 0.1 mol/L cacodylate buffer containing 3mmol/L CaCl2, and then they were dehydrated in increasing concentrations of ethanol (50%, 70%, 90%, and 100% with each treatment lasting 10 days). After dehydration, the samples were embedded using Technovit 9100 NEU (Heraeus Kulzer GmbH; supplied by Emgrid Australia Pty. Ltd., The Patch, Victoria, Australia) following the protocols from the manufacturer. The resin-embedded sample surfaces were acid-etched with 37% phosphoric acid for 12 s, followed by 5% sodium hypochlorite for 5 min, and coated with gold. SEM (SIGMA VP; Carl Zeiss, Germany) and back-scatter SEM were performed to investigate the morphology of osteocytes and the distribution of minerals in the samples (Jaiprakash et al. 2012, Prasadam et al. 2014).

Histology

The specimens for histological examination were decalcified with 0.5 mol/L ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA), pH 7.4, for 8 weeks, and decalcification was confirmed by radiographic analysis. The samples were then embedded in paraffin wax and 5-μm thick slices were sectioned using a microtome. Hematoxylin and eosin staining was performed to detect the osteonecrotic areas in the samples. The average number of osteocyte nuclei and empty lacunae was counted by calculating 5 fields per section. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferased UTP nick end-labeling (TUNEL) assay was used to detect cells undergoing apoptosis by labeling DNA strand breaks. The Frag EL DNA fragmentation detection kit (QIA33; Calbiochem) was also used to identify the apoptosis of osteocytes. TUNEL-positive osteocytes were counted in 5 defined areas per section (0.95 mm2 per area). Protocols for immunohistochemical (IHC) staining (Xiao et al. 2004) were used to detect the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) using rabbit anti-human iNOS IgG (0.2 µg/µL; Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL), cytochrome C using mouse anti-human IgG (50 µM; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) and Bax using rabbit anti-human IgG (0.1 mM; Cell Signaling Technology). We counted the positively and negatively stained osteocytes in 5 areas per section using Axio Vision Rel 4.8 software, and calculated the percentages.

Animal model

It has been reported that there is increased osteocyte apoptosis during the development of femoral head osteonecrosis in spontaneously hypertensive rats (Shibahara et al. 2000). Ethical approval was granted by the animal ethics committee of Queensland University of Technology. 16 male spontaneous hypertensive rats (SHRs) were purchased from the Animal Resource Centre in Perth, Western Australia. The rats were divided into 2 groups: the aminoguanidine treatment group (AMG group) and a control group (osteonecrosis group). The AMG group received 1mg/mL AMG in the drinking water from the fifth week to the seventeenth week, at which time they were killed. The control group did not receive any treatment. All the SHRs were killed at the seventeenth week of life, and the bilateral femoral heads were extracted and kept in 4% paraformaldehyde for micro-CT evaluation (μCT40; Scanco, Brüttisellen, Switzerland). After decalcification, the samples were embedded in paraffin and sectioned for histology. TUNEL assay, hematoxylin and eosin staining, and IHC staining for iNOS, cytochrome C, and Bax were performed as mentioned above. The TUNEL-positive osteocytes and positively and negatively stained osteocytes in IHC were counted in 5 fields per section and percentages calculated as described above.

Statistics

Data analysis was performed using SPSS software version 16.0. Independent t-test was used for comparison of data between the 2 groups. Any value of p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Increased osteocyte apoptosis in human samples with non-traumatic osteonecrosis

Conventional radiographic and computed tomography images showed that all of the femoral heads collected were at Ficat stage III to IV (Figure 1). All samples were assessed for histological changes in the osteonecrotic region and compared with the control samples (the no-ON and OA groups); osteonecrotic bone areas showed similar changes in all samples collected for the study. The black arrows in Figure 1e show the area of osteonecrosis and the yellow arrows show the empty lacunae. The average percentage of empty lacunae was higher in the osteonecrosis areas than in the region with no osteonecrosis and the OA group (p < 0.001). A representative TUNEL-stained section confirmed that there were more osteocytes undergoing apoptosis in the osteonecrotic areas than in the region with no osteonecrosis and the OA group. Figure 1 shows the average number of apoptotic osteocytes in the groups as a bar graph. There were significantly more apoptotic osteocytes in the osteonecrosis group (p < 0.001).

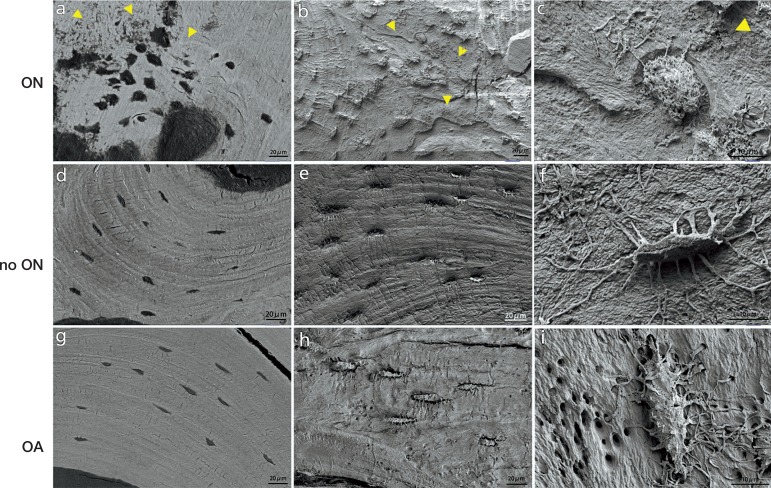

Altered osteocyte morphology in human osteonecrosis samples

Resin-embedded samples from 5 patients were examined by SEM to investigate the morphological changes in osteocytes in osteonecrotic bone. In back-scatter mode, the osteocytes from regions with no osteonecrosis in the 2 control groups were well organized and the mineral matrix was regular in distribution, whereas the osteocytes in the ON group showed disorder in distribution and the mineral matrix was irregular and disorganized. After acid etching to remove the mineral around osteocytes, the osteocyte morphology consisted of a clear cell body and dendrites. In the 2 control groups, the osteocytes had numerous dendritic processes and a clear dendritic process could be seen extending from the canaliculi. However, in the ON group, the osteocyte cell body was significantly changed with a rough, rounded, and lysed appearance and the dendritic processes were atrophic and reduced in number (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Osteocyte morphology in osteonecrosis samples. Panel a shows the mineral-disrupted distribution in the osteonecrosis group. Compare this with that in the control groups (panels d and g). The yellow arrowheads indicate the mineral-disrupted distribution area. In the control groups, the osteocytes extended numerous dendritic processes and a clear dendritic process could be seen coming from the canaliculi (panels e, f, h, and i). However, in the osteonecrosis group, the osteocyte cell body was significantly changed with a rough, rounded, and lysed appearance and the dendritic processes were atrophic and reduced in number (panels b and c).

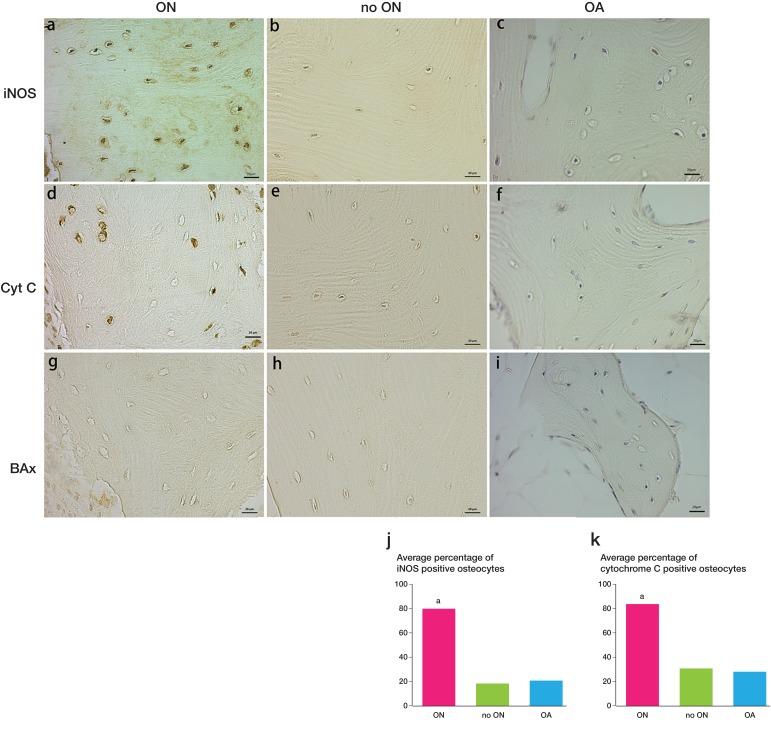

Increased iNOS and cytochrome C expression in human osteonecrosis samples

The IHC staining of iNOS showed that numerous osteocytes in the ON group expressed iNOS whereas the numbers of positive cells decreased in the 2 control groups (the no-ON group and the OA group). The difference between the ON group and the control groups was statistically significant (p < 0.001) (Figure 3j). The expression of cytochrome C also showed a significant difference between the ON group and either of the control groups (p < 0.001). The expression of Bax was not detectable in osteocytes in each group (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

iNOS and cytochrome C distribution in osteonecrosis samples. Increased numbers of iNOS-positive osteocytes in osteonecrosis samples (panel a) compared with expression in the controls (panels b, c, and j). The expression of cytochrome C was also different in the osteonecrosis group and the controls (panels d, e, f, and k). No expression of Bax was detected (panels g, h, and i). ap < 0.001 (in panels j and k).

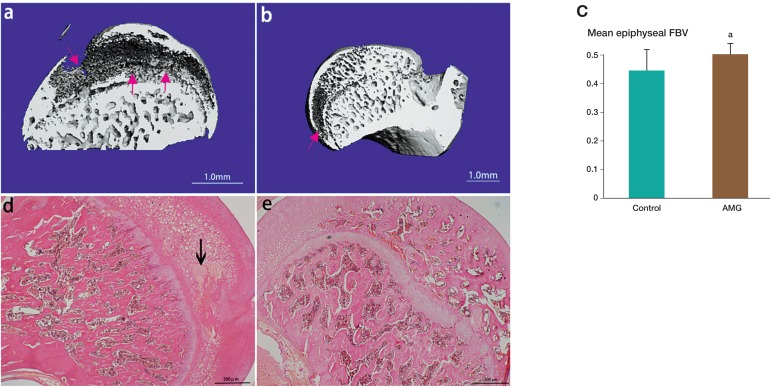

Reduction of osteonecrosis in spontaneous hypertensive rats using iNOS inhibitor

The mid-sagital section of the 3D reconstruction of the rat femoral head showed that the osteonecrosis area was in the subchondral bone in SHRs. The mean fractional trabecular bone volume of the ON group was 0.45 (± 0.07) (n = 8) whereas it was 0.51 (± 0.03) in the AMG treatment group (n = 8). There was a statistically significant difference between the 2 groups (p = 0.01), indicating an improvement with AMG treatment in SHR rats. In the hematoxylin and eosin stained images, bone in the subchondral area in the AMG treatment group showed significant improvement in normal ossification (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The mid-sagittal section of the 3D reconstruction and also histology of the femoral head in spontaneous hypertensive rats (SHRs). The red arrow shows the osteonecrotic area in the subchondral bone (panels a and b). The mean fractional trabecular bone volume of the osteonecrosis group was less than that of the AMG treatment group (panel c). In the hematoxylin and eosin stained images, the area of osteonecrosis is shown with a black arrow (panel d). In the AMG treatment group, the bone showed significant improvement (normal ossification) (panel e). ap < 0.05 (in panel c).

Histological evidence of AMG inhibiting apoptosis of osteocytes

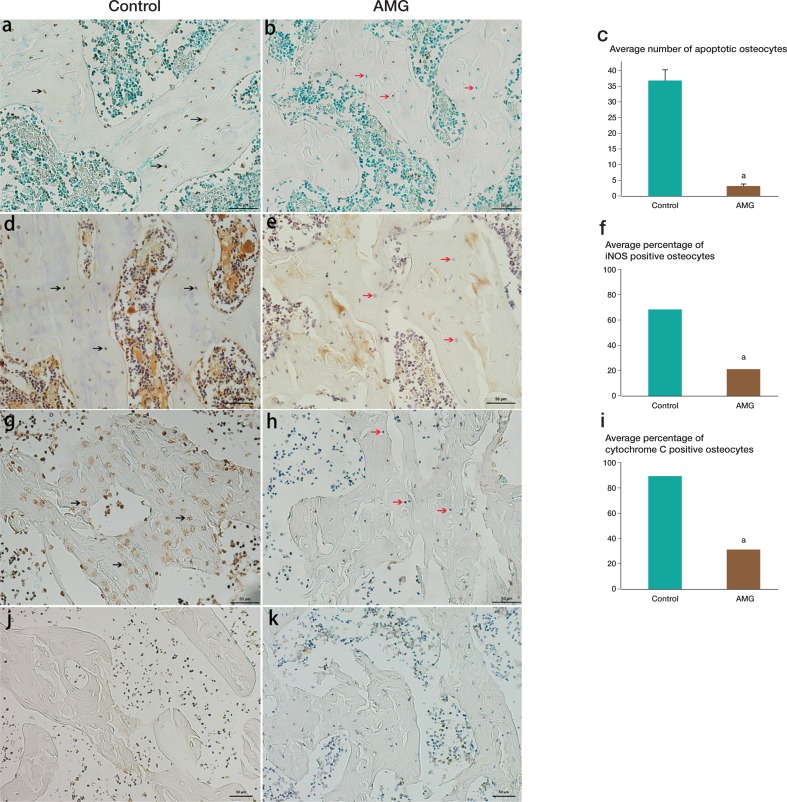

TUNEL assay showed that very few osteocytes were undergoing apoptosis in the AMG group, but a large number of apoptotic osteocytes were found in the untreated group. There was a significant difference between the 2 groups (p < 0.001). The expression of iNOS and cytochrome C was in agreement with the results of TUNEL staining: there were reduced numbers of iNOS- and cytochrome C-positive osteocytes in the AMG treatment group relative to the untreated group. No IHC staining of Bax was detected in either group (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Results of TUNEL assay and distribution of cytochrome C and Bax in the rat femoral head. In the AMG group, very few osteocytes were undergoing apoptosis (panels b and c) whereas a large number of apoptotic osteocytes were found in the untreated group (panel a; black arrows show apoptotic cells). The expression of iNOS (panels d and e) and cytochrome C (panels g and h) showed reduced numbers of iNOS-positive osteocytes (panel f) and cytochrome C-positive osteocytes (panel i) with AMG treatment than in the untreated group. No Bax-positive staining was detected in either group (panel j and k). ap < 0.05.

Discussion

The osteocyte is the most numerous and longest-living cell in bone, with a lifespan of as much as decades in a mineralized environment. Osteocytes are not inactive and static cells in bone; they have an active role in regulating bone homeostasis. For example, they can act as an orchestrator of bone remodeling through regulation of osteoblasts and osteoclasts, and they can also function as endocrine cells. Osteocytes can die through apoptosis under physiological conditions, but it is abnormal that large numbers of osteocytes undergo apoptosis. It has been reported that increased numbers of osteocytes undergo apoptosis in glucocorticoid- and alcohol-induced osteonecrosis (Tsuji et al. 2006, Maurel et al. 2012, Weinstein 2012). Alcohol abuse and glucocorticoid therapy are 2 major reasons for non-traumatic osteonecrosis (Seamon et al. 2012). Alcohol and glucocorticoids may have direct toxic effects on bone cells, and cause them to become apoptotic. It has recently been reported that increased osteocyte and osteoblast apoptosis was not only found in corticosteroid- and alcohol-induced osteonecrosis, but also in idiopathic, non-trauma induced osteonecrosis (Mutijima et al. 2014). In the present study, we confirmed that a large number of osteocytes undergo apoptosis in idiopathic, non-traumatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head and we found for the first time that the morphology of osteocytes changes during the process of apoptosis.

The exact mechanisms of non-traumatic osteonecrosis remain elusive; many studies in the past decade have shown that the pathogenesis involves different pathways and factors (Fessel 2013). It was found that the expression of OPG, RANK, and RANKL was higher in the necrotic part than in the normal region in osteonecrosis samples (Samara et al. 2014). Another study showed different levels of bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) in the normal and necrotic sites of femoral heads from patients with avascular necrosis (Samara et al. 2013). In the present study, the expression of iNOS increased in osteonecrosis samples relative to control samples, suggesting that more nitric oxide was being produced in osteonecrosis samples. When the concentration of nitric oxide is within the physiological range, it is thought to be protective, but large amounts of nitric oxide are proinflammatory and injurious. The possible mechanism may involve the effects on the mitochondrion permeability transition pore (mPTP). The opening of mPTPs by high concentrations of nitric oxide were found to be related to disulfide bond formation and the oxidizing effects of ONOO-, while the inhibitory effect of physiological concentrations is related to S-nitrosylation (Ohtani et al. 2012). In the present study, we found that cytochrome C, which is situated between the outer membrane and the inner membrane of the mitochondrion and is crucial to cell apoptosis, was more highly expressed in the osteonecrosis samples. Interestingly, Bax protein, a pro-apoptotic protein, also affects the mitochondrion, and apoptosis was not detected in either normal samples or in osteonecrosis samples. Thus, we can infer that the apoptosis of numerous osteocytes in the osteonecrosis group was mainly associated with the consistently high expression of iNOS and cytochrome C. This indicates that in non-traumatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head, the increased production of nitric oxide causes opening of mPTPs, increases the output of cytochrome C, and then causes apoptosis in osteocytes.

Using AMG, an inhibitor of iNOS, we also demonstrated that inhibition of iNOS could prevent non-traumatic osteonecrosis in an animal model. AMG has been used to treat experimental colitis in a rat model, which is due to increase in iNOS-induced intestinal cell apoptosis (Ercin et al. 2009, Ito et al. 2010). In the present study, the fractional bone volume in the AMG group was higher than that in the control group, which indicates that AMG may have a role in preventing osteonecrosis. Our further investigation using TUNEL assay and IHC staining of iNOS, cytochrome C, and Bax showed that the group that was not treated with AMG had more TUNEL-positive osteocytes, and the expression of iNOS and cytochrome C was higher. These findings confirm that the iNOS inhibitor AMG can reduce the production of iNOS in osteocytes and thus cause a reduction in cytochrome C release and apoptosis of osteocytes. However, the apoptosis signaling pathway is not only mediated through the mitochondrion; extracellular signals can activate caspase through Fas/CD95, and this pathway may also play a role in the apoptosis of osteocytes in non-traumatic osteonecrosis (Kogianni et al. 2004). In the present study, the use of AMG in SHRs had some therapeutic effects in this rat model, so further studies will investigate the effect of AMG on other apoptosis pathways in osteocytes.

Our study provides evidence that there was increased expression of iNOS in idiopathic, non-traumatic osteonecrosis, which may have been responsible for the increased release of cytochrome C, and therefore the increased apoptosis of osteocytes. AMG has shown therapeutic effects in the apoptosis of osteocytes in SHRs. This suggests a possible avenue for the treatment of osteonecrosis through the inhibition of apoptosis in osteocytes.

Acknowledgments

JW: worked on experimental design, carried out experimental work, and wrote the manuscript. AK: worked on experimental design and carried out experimental work. SL: carried out experimental work. RC: worked on experimental design and wrote the manuscript. JDN: worked on manuscript design and collected data. YX: worked on the experimental design, carried out experimental work, collected data, and wrote the manuscript.

Jun Wang was supported by the Chinese Scholarship Council and the project was partially supported by the Queensland Orthopaedic Trust and the Prince Charles Hospital Research Foundation.

The authors declare that there were no competing interests.

References

- Assouline-Dayan Y, Chang C, Greenspan A, Shoenfeld Y, Gershwin ME. Pathogenesis and natural history of osteonecrosis . Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2002;32(2):94–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonewald L. The amazing osteocyte . J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:229–38. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calder JD, Buttery L, Revell PA, Pearse M, Polak JM. Apoptosis--a significant cause of bone cell death in osteonecrosis of the femoral head . J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86(8):1209–13. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.86b8.14834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmore S. Apoptosis: a review of programmed cell death . Toxicol Pathol. 2007;35(4):495–516. doi: 10.1080/01926230701320337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ercin CN, Yesilova Z, Korkmaz A, Ozcan A, Oktenli C, Uygun A. The effect of iNOS inhibitors and hyperbaric oxygen treatment in a rat model of experimental colitis . Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54(1):75–9. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0498-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fessel J. There are many potential medical therapies for atraumatic osteonecrosis . Rheumatology (Oxford) 2013;52(2):235–41. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kes241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffman KM, Bowers JR, Dailiana Z, Huebner JL, Urbaniak JR, Kraus VB. Synovial fluid metabolites in osteonecrosis . Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46(3):523–8. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito J, Uchida H, Yokote T, Ohtake K, Kobayashi J. Fasting-induced intestinal apoptosis is mediated by inducible nitric oxide synthase and interferon-{gamma} in rat . Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2010;298(6):G916–26. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00429.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaiprakash A, Prasadam I, Feng JQ, Liu Y, Crawford R, Xiao Y. Phenotypic characterization of osteoarthritic osteocytes from the sclerotic zones: a possible pathological role in subchondral bone sclerosis . Int J Biol Sci. 2012;8(3):406–17. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.4221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogianni G, Mann V, Ebetino F, Nuttall M, Nijweide P, Simpson H, Noble B. Fas/CD95 is associated with glucocorticoid-induced osteocyte apoptosis . Life Sci. 2004;75(24):2879–95. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Poulos TL. Structure-function studies on nitric oxide synthases . J Inorg Biochem. 2005;99(1):293–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2004.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malizos KN, Karantanas AH, Varitimidis SE, Dailiana ZH, Bargiotas K, Maris T. Osteonecrosis of the femoral head: etiology, imaging and treatment . Eur J Radiol. 2007;63(1):16–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2007.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mankin HJ, Dorfman H, Lippiello L, Zarins A. Biochemical and metabolic abnormalities in articular cartilage from osteo-arthritic human hips. II. Correlation of morphology with biochemical and metabolic data . J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1971;53(3):523–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurel DB, Boisseau N, Benhamou CL, Jaffre C. Alcohol and bone: review of dose effects and mechanisms . Osteoporos Int. 2012;23(1):1–16. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1787-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutijima E, De Maertelaer V, Deprez M, Malaise M, Hauzeur JP. The apoptosis of osteoblasts and osteocytes in femoral head osteonecrosis: its specificity and its distribution. Clin Rheumatol. 2014;15(4) doi: 10.1007/s10067-014-2607-1. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtani H, Katoh H, Tanaka T, Saotome M, Urushida T, Satoh H, Hayashi H. Effects of nitric oxide on mitochondrial permeability transition pore and thiol-mediated responses in cardiac myocytes . Nitric Oxide. 2012;26(2):95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2011.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan L, Song K, Hu F, Sun W, Lee I. Nitric oxide induces apoptosis associated with TRPV1 channel-mediated Ca(2+) entry via S-nitrosylation in osteoblasts . Eur J Pharmacol. 2013;715(1)(3):280–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasadam I, Zhou Y, Du Z, Chen J, Crawford R, Xiao Y. Osteocyte-induced angiogenesis via VEGF-MAPK-dependent pathways in endothelial cells . Mol Cell Biochem. 2014;386(1-2):15–25. doi: 10.1007/s11010-013-1840-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samara S, Dailiana Z, Varitimidis S, Chassanidis C, Koromila T, Malizos KN, Kollia P. Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) expression in the femoral heads of patients with avascular necrosis . Mol Biol Rep. 2013;40(7):4465–72. doi: 10.1007/s11033-013-2538-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samara S, Dailiana Z, Chassanidis C, Koromila T, Papatheodorou L, Malizos KN, Kollia P. Expression profile of osteoprotegerin, RANK and RANKL genes in the femoral head of patients with avascular necrosis . Exp Mol Pathol. 2014;96(1):9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2013.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seamon J, Keller T, Saleh J, Cui Q. The pathogenesis of nontraumatic osteonecrosis. Arthritis. 2012;8(11):1–11. doi: 10.1155/2012/601763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibahara M, Nishida K, Asahara H, Yoshikawa T, Mitani S, Kondo Y, Inoue H. Increased osteocyte apoptosis during the development of femoral head osteonecrosis in spontaneously hypertensive rats . Acta Med Okayama. 2000;54(2):67–74. doi: 10.18926/AMO/32287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H, Wolf WP, Akiyama K, Horstman D, Grant P, Cannavino C, Bing RJ. Effect of inhibitors of inducible form of nitric oxide synthase in infarcted heart muscle . Proc Assoc Am Physicians. 1996;108(2):173–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji M, Ikeda H, Ishizu A, Miyatake Y, Hayase H, Yoshiki T. Altered expression of apoptosis-related gene in osteocytes exposed to high-dose steroid hormones and hypoxic stress . Pathobiology. 2006;73(6):304–9. doi: 10.1159/000099125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein RS. Glucocorticoid-induced osteonecrosis . Endocrine. 2012;41(2):183–90. doi: 10.1007/s12020-011-9580-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Y, Haase H, Young WG, Bartold PM. Development and transplantation of a mineralized matrix formed by osteoblasts in vitro for bone regeneration . Cell transplantation. 2004;13(1):15–25. doi: 10.3727/000000004772664851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youm YS, Lee SY, Lee SH. Apoptosis in the osteonecrosis of the femoral head . Clin Orthop Surg. 2010;2(4):250–5. doi: 10.4055/cios.2010.2.4.250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalavras C, Dailiana Z, Elisaf M, Bairaktari E, Vlachogiannopoulos P, Katsaraki A, Malizos KN. Potential aetiological factors concerning the development of osteonecrosis of the femoral head . Eur J Clin Invest. 2000;30(3):215–21. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.2000.00621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]