Abstract

Background and purpose

The influence of hospital volume on the outcome of total knee joint replacement surgery is controversial. We evaluated nationwide data on the effect of hospital volume on length of stay, re-admission, revision, manipulation under anesthesia (MUA), and discharge disposition for total knee replacement (TKR) in Finland.

Patients and methods

59,696 TKRs for primary osteoarthritis performed between 1998 and 2010 were identified from the Finnish Hospital Discharge Register and the Finnish Arthroplasty Register. Hospitals were classified into 4 groups according to the number of primary and revision knee arthroplasties performed on an annual basis throughout the study period: 1–99 (group 1), 100–249 (group 2), 250–449 (group 3), and ≥ 450 (group 4). The association between hospital procedure volume and length of stay (LOS), length of uninterrupted institutional care (LUIC), re-admissions, revisions, MUA, and discharge disposition were analyzed.

Results

The greater the volume of the hospital, the shorter was the average LOS and LUIC. Smaller hospital volume was not unambiguously associated with increased revision, re-admission, or MUA rates. The smaller the annual hospital volume, the more often patients were discharged home.

Interpretation

LOS and LUIC ought to be shortened in lower-volume hospitals. There is potential for a reduction in length of stay in extended institutional care facilities.

Total knee replacement (TKR) is one of the most common orthopedic procedures, and it is expected to increase markedly in volume (Kurtz et al. 2007). Due to the potentially severe complications and the high economic impact of the procedure, efforts to minimize the risks and optimize perioperative efficiency are important.

It has been suggested that increased hospital volume and reduction in length of stay (LOS) at the operating hospital after TKR are related, but there is no consensus (Yasunaga et al. 2009, Marlow et al. 2010, Paterson et al. 2010, Bozic et al. 2010, Styron et al. 2011). In addition, results on the association of hospital volume with re-admission rates (Soohoo et al. 2006b, Judge et al. 2006, Bozic et al. 2010, Cram et al. 2011) and revision risk have been inconclusive (Shervin et al. 2007, Manley et al. 2009, Bozic et al. 2010, Paterson et al. 2010). No-one has tried to study the association between length of uninterrupted institutional care (LUIC), incidence of manipulation under anesthesia (MUA) after TKR, and hospital volume.

By combining 5 national-level registries, we examined possible associations between hospital volume and LOS, LUIC, discharge disposition, number of re-admissions within 14 and 42 days, MUA, and revisions after TKR for all knee arthroplasties performed in Finland between 1998 and 2010.

Patients and methods

All public and private hospitals in Finland are obliged to report all surgical procedures to the Finnish National Institute of Health and Welfare. The present study was based on the PERFECT hip and knee replacement databases (Mäkelä et al. 2011), which use data from the Hospital Discharge Register (maintained by the Finnish National Institute of Health and Welfare), cause of death statistics published by Statistics Finland, the Social Insurance Institution’s drug prescription register and drug reimbursement register, and the Finnish Arthroplasty Register.

We evaluated whether there were any associations between hospital volume and LOS, LUIC, discharge disposition, unscheduled re-admissions, revisions, and MUA. LOS was counted as the number of postoperative nights in hospital until discharge, as recorded in the Hospital Discharge Register. LOS terminated in either discharge to home, transfer to another facility, or death. LUIC was defined as the combined surgical treatment period and any immediately following period of uninterrupted institutional care. Any rehabilitation given in an outpatient setting or at home is not included in LUIC. LUIC ended in either death or discharge of the patient to home. LUIC includes patient transfers to another facility such as an old people’s home or institution run by a social welfare organization. In the analyses, the maximum length of institutional care was limited to 60 days. It was considered that if a patient stayed in a healthcare facility for more than 60 days after TKR, the reason was not directly related to the operation. The study period was from 1998 to 2010. Patients were followed until the end of 2011.

Hospital grouping

Hospitals were classified into 4 groups according to the number of primary and revision TKRs (Finnish version of Nordic Medico-Statistical Committee (NOMESCO) codes, NGB10 (unicondylar knee arthroplasty), NGB20–60 (TKRs), NGB99 (other knee arthroplasty), NGC00–NGC99 (revision knee arthroplasties)) performed annually throughout the study period in 80 hospitals: 1–99 (low-volume hospitals, group 1), 100–249 (medium-volume hospitals, group 2), 250–449 (high-volume hospitals, group 3), and ≥ 450 (very high-volume hospitals, group 4) (Supplementary data, Appendix 1). Grouping was done based on the annual volume of a hospital, with the annual period defined to be from January 1 to December 31. No uniform categorization of hospital volume exists in the literature, so the cut-off points for the different hospital volume groups were chosen arbitrarily. We consider, however, that this categorization enabled us to obtain properly-sized groups for analysis. Group 4 was used as the reference group in the statistical analyses.

Altogether, 80 hospitals were involved. Hospitals whose volume group changed during the study period were also included. 41 hospitals showed change of group (knees), 9 of them twice and 3 of them 3 times. All the very high-volume hospitals were university hospitals, except for 1 between 2003 and 2008 and except for 3 in the period 2009–2010.

Inclusion criteria

The study population was formed by selecting operations from the Finnish Arthroplasty Register and the Hospital Discharge Register according to the WHO International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) diagnosis (ICD-10. 2010), applying the following criteria: M17.0/M17.1 for primary osteoarthritis (OA), associated with a code for primary TKR performed over the period 1998–2010. The codes for primary TKR were NGB20, NGB30, NGB40, and NGB50. The accuracy of the diagnosis of primary OA was double-checked against the relevant data in the Finnish Arthroplasty Register. Only patients’ first TKRs in the study period (January 1, 1998 to December 31, 2010) were included in the analyses. Total knee replacements—not patients—were evaluated when the length of the surgical treatment period, length of institutional care, and unscheduled re-admissions were considered. The total number of TKRs included in the analysis was 59,696. However, with respect to revisions and MUA, only patients with unilateral TKR (n = 47,217) over the period 1987–2011 were evaluated (Supplementary data, Appendix 2), as the laterality of the MUA and revision was not reliably coded in the Hospital Discharge Register.

Exclusion criteria

TKRs performed for secondary OA were excluded (Supplementary data, Appendix 3). The manifestation of the diagnosis of secondary knee OA was noted retrospectively from the beginning of 1987. A patient was excluded from the study if a diagnosis of secondary knee OA had been recorded in the Hospital Discharge Register between the beginning of 1987 and the day of the operation. Patients in the Social Insurance Institution database who were eligible for reimbursement for the sequelae of transplantation, uremia requiring dialysis, rheumatoid arthritis, or connective tissue disease were excluded from the study. In addition, we excluded patients with hip or other knee arthroplasty performed simultaneously, patients who were residents of Åland, and patients who were not Finnish citizens.

Unscheduled re-admission

An unscheduled re-admission was recorded if a patient was re-admitted to hospital or had required medical attention in an outpatient department or emergency unit of any hospital in Finland during the first 2 or 6 weeks after discharge. Re-admission within 2 weeks was chosen to identify early complications. Re-admission within 6 weeks was chosen to estimate the total unplanned re-admission rate. In Finland, scheduled postoperative visits usually take place between 8 and 12 weeks.

Revision

Searches for revision of the same knee after primary TKR were conducted in both the Finnish Arthroplasty Register and the Hospital Discharge Register using NOMESCO codes NGC00–NGC99. Patients were followed until the end of 2011.

Statistics

We used Poisson regression models for LOS and LUIC, and logistic regression models for revisions, re-admissions, MUA, and discharge disposition at the individual level, with hospital volume (classified) included among the explanatory variables. Adjusted estimates are given for all the dependent variables. In addition, 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were determined. The patient’s age (under 40 years or over 40 years (divided into nine 5-year incremental groups up to age 85, and over 85 years)), sex, any previous TKR, and co-morbidities were included in all the adjusted analyses. The LOS and LUIC models also included dummy variables for the operation year to exclude bias from the universal annual reduction in LOS and LUIC and annual decrease in total volume of low-volume hospitals. The LOS analyses were also repeated with discharge to home included as a confounding factor.

Co-morbidities were determined from diagnoses obtained from the Hospital Discharge Register (from any hospital the patient had been hospitalized at) from the beginning of 1987 to the date of operation. In addition, the Social Insurance Institution database for eligibility for reimbursement, including the use of drugs, was used to adjust for co-morbidity (Supplementary data, Appendix 4). We believe that the methods used to collect the data and determine co-morbidities makes any single-clinic reporting bias negligible. The illnesses chosen for adjustment were such that they may have had an effect on prosthesis survivorship after TKR (Jämsen et al. 2013), on the length of stay in the hospital, or on the rate of complications. Each co-morbid condition was included individually in the models, and therefore adjusted for separately in the analyses. Length of follow-up was taken into account in the adjustment of the rates of MUA and revisions. Death of a patient ended follow-up of that patient. In the analyses of MUA, both LOS and LUIC were included one at a time in the regression models in addition to the explanatory variables already mentioned.

As the deaths were evenly distributed across the hospital volume groups in terms of the proportions of patients in the groups, and the censoring of cases in the analyses of length of stay occurred in only about 0.1% of the operations studied, we do not consider that censoring was a problem in performing the LOS, LUIC, or short-term outcome (2- and 6-week re-admission) analyses. Censoring due to death in the longer term is, however, a more crucial issue, and in our study this had to be taken into account in the assessment of revisions and MUA. We included the individual level-variable describing the length of follow-up (in days) in the logistic regression models to control for the effect of censoring on the dependent variable.

The bias from bilateral observations was minimized by only including a patient’s first TKR in the analyses for LOS, LUIC, and re-admissions, and only unilateral cases in the analyses of revision and MUA.

Results

LOS and LUIC

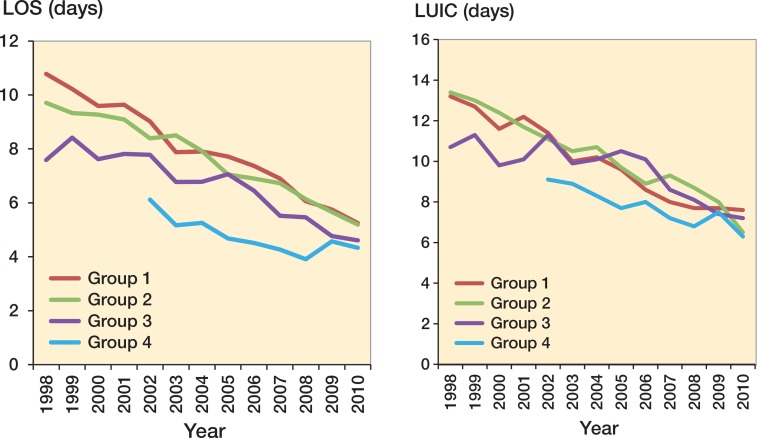

Both LOS and LUIC declined steadily during the study period (Figure 1 and Table 1). Poison regression adjusting for age, sex, any previous TKR, and co-morbidities showed that the larger the hospital volume, the shorter the risk-adjusted average LOS and LUIC. Distributions of age, sex, and any previous TKR in the volume groups are given in Supplementary data, Appendix 5. LOS fell more rapidly in group 1 than in group 4. In 520 cases, the LUIC cut-off was 60 days (0.87% of the cases). We also tested the LOS results with discharge disposition added as a confounding factor in addition to age, sex, any previous TKR, and co-morbidities, and no change emerged.

Figure 1.

LOS: annual mean length of stay (surgical treatment period) in days for primary total knee arthroplasty in different hospital volume groups. LUIC: annual mean length of uninterrupted institutional care in days for primary total knee arthroplasty in different hospital volume groups. Between 1998 and 2001 there were no hospitals in hospital volume group 4.

Table 1.

Group-specific estimated mean LOS and LUIC during the study period 1998–2010, their estimation uncertainty (95% confidence intervals), and numbers of TKRs

| Group | LOS | 95% CI | LUIC | 95% CI | No. of TKRs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8.60 | 8.53–8.67 | 10.72 | 10.58–10.86 | 11,661 |

| 2 | 7.59 | 7.54–7.63 | 10.18 | 10.07–10.28 | 21,679 |

| 3 | 6.14 | 6.10–6.18 | 9.12 | 9.00–9.26 | 12,966 |

| 4 | 4.51 | 4.47–4.55 | 7.39 | 7.26–7.51 | 13,390 |

LOS: mean length of stay (surgical treatment period) in days;

LUIC: mean length of uninterrupted institutional care in days;

TKR: total knee replacement.

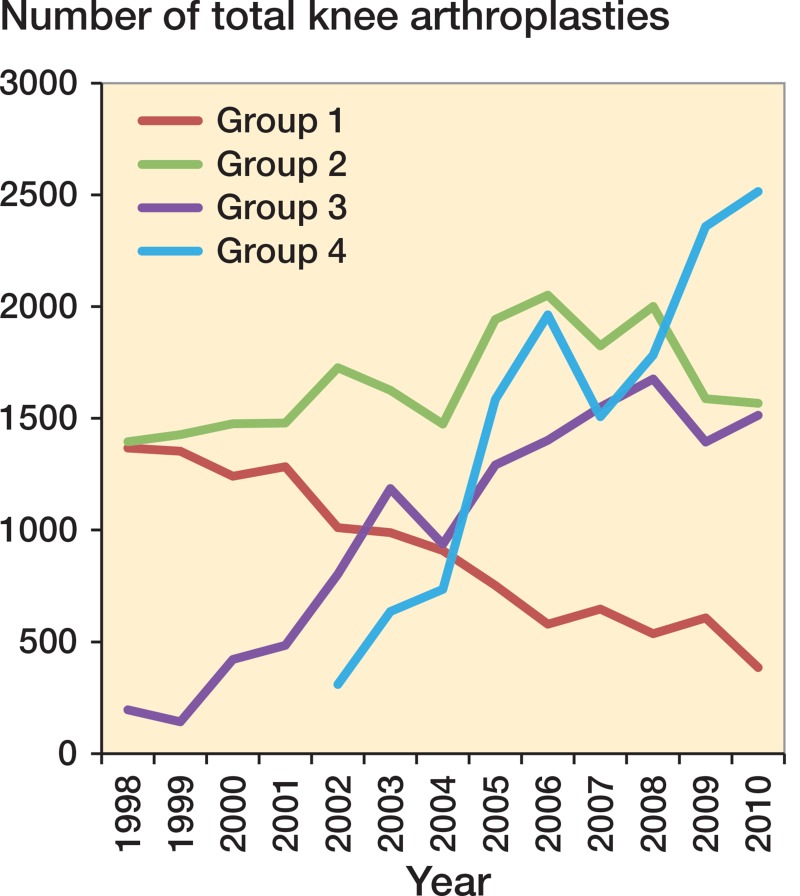

If all the TKRs in Finland between 2002 and 2010 had been performed in the very high-volume hospitals, total LOS would have decreased by 66,355 days (Figure 2). This would have meant a saving of 1.4 inpatient care days per operated patient.

Figure 2.

Annual number of total knee replacements (TKRs) in different hospital volume groups. Between 1998 and 2001, there were no hospitals in hospital volume group 4.

Discharge disposition

After adjusting for age, sex, previous TKR, and co-morbidities, patients were less frequently discharged directly to home from the group-4 hospitals than from the group-3 hospitals (OR = 1.40, CI: 1.32–1.48), group-2 hospitals (OR = 2.07, CI: 1.96–2.19), or group-1 hospitals (OR = 3.08, CI: 2.86–3.32).

Revisions, re-admissions, and MUAs

In the data, the average follow-up time after surgery was 6 years. The adjusted data showed fewer revisions in the group-4 hospitals than in either the group-2 hospitals (OR = 1.27, CI: 1.12–1.44) or the group-3 hospitals (OR = 1.20, CI: 1.05–1.37). However, there were no statistically significant differences in revisions in groups 4 and 1 (Table 2). Re-admissions in 2 weeks (OR = 1.10, CI: 1.00–1.21) and in 6 weeks (OR = 1.11, CI: 1.03–1.19) were more common in group-1 hospitals than in group-4 hospitals. Had all the group-1 TKRs done between the years 2002 and 2010 in Finland been performed in the very-high-volume hospitals, this would have meant 159 (1.7%) fewer re-admissions within 42 days.

Table 2a.

Adjusted odds ratios for unscheduled re-admissions within 14 and 42 days, for revisions, and for manipulation under anesthesia (MUA)

| Re-admissions within 14 days |

Re-admissions within 42 days |

Revisions |

MUA |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groups | OR | 95% WCI | OR | 95% WCI | OR | 95% WCI | OR | 95% WCI |

| 1 vs. 4 | 1.10 | 1.00–1.21 | 1.11 | 1.03–1.19 | 1.08 | 0.93–1.26 | 0.92 | 0.74–1.15 |

| 2 vs. 4 | 1.04 | 0.97–1.12 | 1.05 | 0.99–1.11 | 1.27 | 1.12–1.44 | 1.14 | 0.97–1.34 |

| 3 vs. 4 | 0.98 | 0.90–1.06 | 0.99 | 0.93–1.05 | 1.20 | 1.05–1.37 | 1.44 | 1.22–1.70 |

Logistic regression models were used to adjust for patient age, sex, any previous TKR, and co-morbidities. In addition, length of follow-up was taken into account in the adjustment of the revision rates. WCI: Wald confidence interval.

MUA was less frequent in the group-4 hospitals than in the group-3 hospitals (OR = 1.44, CI: 1.22–1.70). However, there was no statistically significant difference in MUA between group 4 and other groups (Table 2). Short los was not associated with a higher risk of MUA.

Table 2b.

Unadjusted percentage and number of re-admissions within 14 and 42 days, revisions, and manipulation under anesthesia (MUA)

| Re-admissions within 14 days |

Re-admissions within 42 days |

Revisions |

MUA |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10.1 | 853 | 18.5 | 1,559 | 5.2 | 439 | 2.4 | 379 |

| 2 | 10.3 | 1,669 | 19.2 | 3,095 | 5.4 | 873 | 2.4 | 379 |

| 3 | 9.7 | 1,020 | 18.5 | 1,943 | 4.7 | 489 | 3.1 | 329 |

| 4 | 10.1 | 1,230 | 19.4 | 2,356 | 3.5 | 421 | 2.3 | 284 |

Regarding revisions and MUA, only patients with unilateral TKR (n = 47,217) over the period 1987–2011 were evaluated.

Discussion

The incidence of TKRs is expected to increase in the ageing western population (Kurtz et al. 2007). It is of importance to identify the factors that influence the outcome and the cost-effectiveness of TKR. We found that knee replacements performed in very-high-volume hospitals were associated not only with shorter LOS and LUIC, but also with higher discharge rates to other institutional care facilities. Shorter LOS was not associated with increased re-admission, revision, or MUA rates.

Validity of the data

A systematic review of the literature found that the level of completeness and accuracy in the Finnish Hospital Discharge Register was satisfactory (Sund 2012). The coverage of knee replacements was 96% in the Finnish Arthroplasty Register relative to the Hospital Discharge Register (Jämsen et al. 2009). The strength of the present study was that it included operation data from both private and public hospitals. We also adjusted our analyses for patient age, sex, any previous TKR, and co-morbidities. In addition, LOS analyses were performed taking discharge disposition into account.

The present study had some limitations. We did not evaluate the association between infections and hospital volume, as registry data on this issue are inaccurate (Jämsen et al. 2009). Our study was based on administrative data, which sets limits to the availability of possible confounding factors. The most important missing confounding factors are surgery in more complicated cases, high BMI, alcohol abuse and smoking, number of other institutional care facilities in the hospital district, the distance between other care facilities and the hospital, the annual arthroplasty volume of surgeons, and the socioeconomic status of patients. Surgery in more complicated cases is more likely to be performed in high-volume and very-high-volume hospitals in Finland. This possibly worsens the complication rates and discharge disposition rates in the higher-volume units. However, we believe that this applies mainly to patients with secondary osteoarthritis, whereas the patient population with primary osteoarhritis is more homogenous. The annual arthroplasty volume of surgeons clearly has an effect on outcomes, and therefore may also affect our results. However, higher-volume hospitals are often teaching hospitals with residents whose annual arthroplasty volume is relatively low, while the lower-volume hospitals have fewer surgeons doing the annual case volume. In addition, some high-volume surgeons in high-volume hospitals also operate in low-volume (private) hospitals. We believe that the number of other institutional care facilities in the hospital district, the distance between other care facilities and the hospital, and patients’ socioeconomic status may also affect LOS and LUIC. We were not able to include these variables in the adjusted analyses. We have no reason to assume that other unobserved confounders such as high BMI, smoking, or alcohol abuse would be unequally distributed across the different hospital volume groups, so, although their effect on outcomes is not taken directly into account, they do not bias the results on volume. Regarding possible over-adjustment, our sample size was rather large, meaning that if the estimates suffer from any bias related to over-adjustment, this bias would be negligible.

Length of stay

It must be understood that LOS is not the most important indicator of hospital quality. However, if the aim is to optimize the whole treatment protocol, it will eventually lead to shorter LOS without compromising quality. By shortening LOS, we can free a large amount of resources in a situation characterized by an increasing need for care and a decreasing number of hospital staff (physicians and nurses).

Several hospital-related factors have been reported to be associated with LOS: surgeon volume, hospital volume, time between surgery and mobilization, and process standardization (such as fast-track programs) (Kreder et al. 2003, Mitsuyasu et al. 2006, Judge et al. 2006, Yasunaga et al. 2009, Bozic et al. 2010, Husted et al. 2010a, Styron et al. 2011, Lau et al. 2012). However, several authors have reported that there is no statistically significant association between hospital volume and LOS (Lavernia and Guzman 1995, Hervey et al. 2003, Marlow et al. 2010, Paterson et al. 2010). Since no uniform categorization of hospital volume has been used in different studies, and because some studies have also included total hip replacements, it is difficult to come to a firm conclusion on this issue.

The association between hospital volume and LOS after TKR has not been evaluated before in Finland. We have shown that the use of hospitalization after TKR diminished annually (between 1998 and 2010) and that hospitalization after TKR was shorter the greater the volume of the hospital. It has been claimed that short LOS is due to transfer of patients to rehabilitation centers (Paterson et al. 2010). This was controlled for in our study, since this kind of inpatient care after TKR is included in LUIC. We also tested this by adding discharge disposition into the LOS modelling, and it did not change our result. Reducing LOS may reduce the unit costs of care if the bed capacity so released can be used for other productive activity.

We showed that very high hospital volume was associated with both shorter LOS and shorter LUIC. LOS decreased in every volume group throughout the study period. An annual decline in LOS after TKRs has also been reported by Cram et al. (2012). The short LOS and LUIC in the very-high-volume centers may have been due to pressure to standardize patient care in order to optimize efficiency and manage patient flow. The decrease in average LOS was faster in the lower-volume hospitals, thus indicating that lower-volume hospitals have enhanced their efficiency faster than the higher-volume hospitals. This may be due to pressure to close some of these hospitals for economic reasons. Also, LUIC decreased, but this was wholly due to the reduction in LOS. Although LOS after TKR have decreased in Finnish hospitals, comparison with Danish fast-track results indicates that there is still potential for further reduction in LOS in Finland (Husted et al. 2012). In the future, patient care after TKR should also be optimized in other institutional care facilities.

Unscheduled re-admissions

The rate of unscheduled re-admissions is commonly used as an indicator in evaluating the outcome of arthroplasties, despite criticism of its use as a basis for assessing quality of care (Weissman et al. 1999, Jimenez-Puente et al. 2004). The reliability of re-admission coding in databases has also been disputed (Keeney et al. 2012). However, the re-admission rate has been used as a key performance indicator (Courtney et al. 2003, Adeyemo and Radley 2007).

A number of studies have evaluated the correlation between hospital volume and re-admissions, and have arrived at conflicting results (SooHoo et al. 2006a, Soohoo et al. 2006b, Judge et al. 2006, Bozic et al. 2010, Cram et al. 2011). Cram et al. (2012) found that a decrease in hospital LOS was associated with increasing re-admission rates during the last decade. This conflicts with other studies, which have found no increase in re-admission rates in the presence of a decrease in LOS (Husted et al. 2010b, Vorhies et al. 2011, Vorhies et al. 2012). In the present study, the patients who were operated on at very high-volume hospitals had a lower probability of re-admission within 2 and 6 weeks of discharge than those who were operated on at low-volume hospitals. Thus, the savings from shorter LOS in very-high-volume hospitals were not cancelled out by a potentially higher rate of re-admissions.

Revisions

There are conflicting data on the association between hospital volume and revision after TKR. Some studies have found hospital volume to be predictive of revision after TKR (Kreder et al. 2003, Judge et al. 2006, Manley et al. 2009, Paterson et al. 2010) while others have not (Shervin et al. 2007, Bozic et al. 2010). Baker et al. (2013) found hospital volume to be associated with lower risk of revision after unicondylar knee replacements. In our study, group-4 hospitals had fewer revisions than group-3 and group-2 hospitals. However, there was no statistically significant difference between groups 1 and 4. In Finland, some of the higher-volume surgeons also operate in low-volume (private) hospitals, while more demanding cases are unlikely to be treated in low-volume hospitals. Thus, this may partly explain this result. Also, only a subgroup of patients with unilateral TKR was included in our analyses of revisions (79% of patients). Patients with bilateral TKR may have a different risk of revision. However, it has been reported that there is no practical difference between analyzing solely unilateral revisions and both unilateral and bilateral revisions (Robertsson and Ranstam 2003, Lie et al. 2004). While hospitals are under pressure to shorten LOS, there is fear of increasing the incidence of MUA due short LOS. Therefore, we also evaluated the association between MUA and LOS (LUIC), and found that short LOS was not associated with an increase in the rate of MUA. Husted et al. (2010b) made the same observation with a fast-track protocol. According to our data, there was no clear association between hospital volume and the rate of MUA. Further studies are needed to examine any association between hospital volume and risk of revision and MUA.

Discharge disposition

The impact of hospital volume and shorter LOS on discharge disposition has scarcely been studied. It has been proposed that patients in higher-volume hospitals are more likely to be directly discharged home (Bozic et al. 2010). However, shorter LOS has been proposed to be associated with a higher likelihood of discharge to an extended institutional care facility (Paterson et al. 2010). We found that hospital volume was inversely correlated to the rate of discharge home.

Pressure to reduce LOS may lead to erroneous patient discharge to an extended institutional care facility. Physical therapy outcomes are not dependent on discharge disposition (Kelly and Ackerman 1999, Chimenti and Ingersoll 2007). Contents of optimal physiotherapy after TKR is not known (Bandholm and Kehlet. 2012). It has also been proposed that discharging a healthy total joint arthroplasty patient to an extended institutional care facility could lead to an increase in the number of unscheduled re-admissions (Bini et al. 2010). Thus, it would be important to make a thorough re-evaluation of which patients would truly need—and would benefit from—discharge to an extended institutional care facility.

.

Summary

We found that LOS was shorter in higher-volume hospitals. Shorter LOS is not associated with a higher re-admission rate, revision rate, or MUA rate. There is potential to reduce LOS in lower-volume hospitals. Re-evaluation of patient discharge to extended institutional care facilities is needed.

Supplementary data

Appendix 1–5 are available at Acta’s website (www.actaorthop.org), identification number 7221.

Acknowledgments

KJP, MP, JP, UH, KM, and VR wrote the manuscript. MP performed the data analysis. All the authors contributed to the conception and design of the study, to critical analysis of the data, to interpretation of the findings, and to critical revision of the manuscript.

No competing interests declared.

References

- Adeyemo D, Radley S. Unplanned general surgical re-admissions - how many, which patients and why? . Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2007;89(4):363–7. doi: 10.1308/003588407X183409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker P, Jameson S, Critchley R, Reed M, Gregg P, Deehan D. Center and surgeon volume influence the revision rate following unicondylar knee replacement: An analysis of 23,400 medial cemented unicondylar knee replacements . J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(8):702–9. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.00520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandholm T, Kehlet H. Physiotherapy exercise after fast-track total hip and knee arthroplasty: Time for reconsideration? . Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93(7):1292–4. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bini SA, Fithian DC, Paxton LW, Khatod MX, Inacio MC, Namba RS. Does discharge disposition after primary total joint arthroplasty affect readmission rates? . J Arthroplasty. 2010;25(1):114–7. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozic KJ, Maselli J, Pekow PS, Lindenauer PK, Vail TP, Auerbach AD. The influence of procedure volumes and standardization of care on quality and efficiency in total joint replacement surgery . J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(16):2643–52. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.01477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chimenti CE, Ingersoll G. Comparison of home health care physical therapy outcomes following total knee replacement with and without subacute rehabilitation . J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2007;30(3):102–8. doi: 10.1519/00139143-200712000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney ED, Ankrett S, McCollum PT. 28-day emergency surgical re-admission rates as a clinical indicator of performance . Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2003;85(2):75–8. doi: 10.1308/003588403321219803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cram P, Lu X, Kates SL, Li Y, Miller BJ. Outliers: Hospitals with consistently lower and higher than predicted joint arthroplasty readmission rates . Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil. 2011;2(4):135–47. doi: 10.1177/2151458511419847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cram P, Lu X, Kates SL, Singh JA, Li Y, Wolf BR. Total knee arthroplasty volume, utilization, and outcomes among medicare beneficiaries, 1991-2010 . JAMA. 2012;308(12):1227–36. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.11153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hervey SL, Purves HR, Guller U, Toth AP, Vail TP, Pietrobon R. Provider volume of total knee arthroplasties and patient outcomes in the HCUP-nationwide inpatient sample. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A(9):1775–83. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200309000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husted H, Hansen HC, Holm G, Bach-Dal C, Rud K, Andersen KL, Kehlet H. What determines length of stay after total hip and knee arthroplasty? A nationwide study in Denmark . Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2010a;130(2):263–8. doi: 10.1007/s00402-009-0940-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husted H, Otte KS, Kristensen BB, Orsnes T, Kehlet H. Readmissions after fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty . Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2010b;130(9):1185–91. doi: 10.1007/s00402-010-1131-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husted H, Jensen CM, Solgaard S, Kehlet H. Reduced length of stay following hip and knee arthroplasty in Denmark 2000-2009: From research to implementation . Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2012;132(1):101–4. doi: 10.1007/s00402-011-1396-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ICD-10 2012. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems 10th revision: Http://Apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2010/en. 2010 ;

- Jämsen E, Huotari K, Huhtala H, Nevalainen J, Konttinen YT. Low rate of infected knee replacements in a nationwide series--is it an underestimate? . Acta Orthop. 2009;80(2):205–12. doi: 10.3109/17453670902947432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jämsen E, Peltola M, Eskelinen A, Lehto MU. Comorbid diseases as predictors of survival of primary total hip and knee replacements: A nationwide register-based study of 96 754 operations on patients with primary osteoarthritis . Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(12):1975–82. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez-Puente A, Garcia-Alegria J, Gomez-Aracena J, Hidalgo-Rojas L, Lorenzo-Nogueiras L, Perea-Milla-Lopez E, Fernandez-Crehuet-Navajas J. Readmission rate as an indicator of hospital performance: The case of Spain . Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2004;20(3):385–91. doi: 10.1017/s0266462304001230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judge A, Chard J, Learmonth I, Dieppe P. The effects of surgical volumes and training centre status on outcomes following total joint replacement: Analysis of the hospital episode statistics for England . J Public Health (Oxf) 2006;28(2):116–24. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdl003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeney JA, Adelani MA, Nunley RM, Clohisy JC, Barrack RL. Assessing readmission databases: How reliable is the information? . J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(8 Suppl):72. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2012.03.032. 6.e1-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly MH, Ackerman RM. Total joint arthroplasty: A comparison of postacute settings on patient functional outcomes . Orthop Nurs. 1999;18(5):75–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreder HJ, Grosso P, Williams JI, Jaglal S, Axcell T, Wal EK, Stephen DJ. Provider volume and other predictors of outcome after total knee arthroplasty: A population study in Ontario . Can J Surg. 2003;46(1):15–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from . J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;2007;89(4):780–5. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau RL, Perruccio AV, Gandhi R, Mahomed NN. The role of surgeon volume on patient outcome in total knee arthroplasty: A systematic review of the literature . BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13(250) doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-13-250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavernia CJ, Guzman JF. Relationship of surgical volume to short-term mortality, morbidity, and hospital charges in arthroplasty . J Arthroplasty. 1995;10(2):133–40. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(05)80119-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lie SA, Engesaeter LB, Havelin LI, Gjessing HK, Vollset SE. Dependency issues in survival analyses of 55,782 primary hip replacements from 47,355 patients . Stat Med. 2004;23(20):3227–40. doi: 10.1002/sim.1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mäkelä KT, Peltola M, Sund R, Malmivaara A, Häkkninen U, Remes V. Regional and hospital variance in performance of total hip and knee replacements: A national population-based study . Ann Med. 2011;43(Suppl 1):S31–8. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2011.586362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manley M, Ong K, Lau E, Kurtz SM. Total knee arthroplasty survivorship in the United States medicare population: Effect of hospital and surgeon procedure volume . J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(7):1061–7. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlow NE, Barraclough B, Collier NA, Dickinson IC, Fawcett J, Graham JC, Maddern GJ. Centralization and the relationship between volume and outcome in knee arthroplasty procedures . ANZ J Surg. 2010;80(4):234–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2010.05243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsuyasu S, Hagihara A, Horiguchi H, Nobutomo K. Relationship between total arthroplasty case volume and patient outcome in an acute care payment system in Japan . J Arthroplasty. 2006;21(5):656–631. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson JM, Williams JI, Kreder HJ, Mahomed NN, Gunraj N, Wang X, Laupacis A. Provider volumes and early outcomes of primary total joint replacement in Ontario . Can J Surg. 2010;53(3):175–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertsson O, Ranstam J. No bias of ignored bilaterality when analysing the revision risk of knee prostheses: Analysis of a population based sample of 44,590 patients with 55,298 knee prostheses from the national Swedish knee arthroplasty register. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2003;4(1) doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shervin N, Rubash HE, Katz JN. Orthopaedic procedure volume and patient outcomes: A systematic literature review . Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;457:35–41. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e3180375514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SooHoo NF, Lieberman JR, Ko CY, Zingmond DS. Factors predicting complication rates following total knee replacement . J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006a;88(3):480–5. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soohoo NF, Zingmond DS, Lieberman JR, Ko CY. Primary total knee arthroplasty in California 1991 to 2001: Does hospital volume affect outcomes? . J Arthroplasty. 2006b;21(2):199–205. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2005.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Styron JF, Koroukian SM, Klika AK, Barsoum WK. Patient vs provider characteristics impacting hospital lengths of stay after total knee or hip arthroplasty . J Arthroplasty. 2011;26(8):1418. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2010.11.008. 26.e1-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sund R. Quality of the Finnish hospital discharge register: A systematic review . Scand J Public Health. 2012;40(6):505–15. doi: 10.1177/1403494812456637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vorhies JS, Wang Y, Herndon J, Maloney WJ, Huddleston JI. Readmission and length of stay after total hip arthroplasty in a national medicare sample . J Arthroplasty. 2011;26(6 Suppl):119–23. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2011.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vorhies JS, Wang Y, Herndon JH, Maloney WJ, Huddleston JI. Decreased length of stay after TKA is not associated with increased readmission rates in a national medicare sample . Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(1):166–71. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-1957-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman JS, Ayanian JZ, Chasan-Taber S, Sherwood MJ, Roth C, Epstein AM. Hospital readmissions and quality of care . Med Care. 1999;37(5):490–501. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199905000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasunaga H, Tsuchiya K, Matsuyama Y, Ohe K. Analysis of factors affecting operating time, postoperative complications, and length of stay for total knee arthroplasty: Nationwide web-based survey . J Orthop Sci. 2009;14(1):10–6. doi: 10.1007/s00776-008-1294-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.