Abstract

Background and purpose

Recent reports on developer bias in unicondylar knee arthroplasty led to concerns about quality of publications regarding knee implants. We therefore compared revision rates of registry and non-registry studies from the beginning of knee arthroplasty up to the present. We assessed the time interval between market introduction of an implant and emergence of reliable data in non-registry studies.

Material and methods

We systematically reviewed registry studies (n = 6) and non-registry studies (n = 241) on knee arthroplasty published in indexed, peer-reviewed international scientific journals. The main outcome measure was revision rate per 100 observed component years.

Results and interpretation

For 82% of the 34 knee implants assessed, revision data from non-registry studies are either absent or poor. 91% of all studies were published in the second and third decade after market introduction. Only 5% of all studies and 1% of all revisions were published in the first decade. The first publications on revision rates of total knee arthroplasty (TKA) started 6 years after market introduction, and reliable data were found from year 12 onward in non-registry studies. However, in unicondylar knee arthroplasty (UKA) the first publications on revision rates could be found first 13 years after market introduction. Revision rates of TKA from non-registry studies were reliable after year 12 following market introduction. UKA revision rates remained below the threshold of registry indices, and failed to demonstrate adjustment towards registries.

Thus, the superiority of registry data over non-registry data regarding outcome measurement was validated.

Recent reports on material safety concerns regarding hip arthroplasty (Godlee 2012, Smith et al. 2012) and publications on developer’s bias regarding knee implants (Labek et al. 2011a, Pabinger et al. 2012) have led to concerns about the quality and reliability of studies on knee arthroplasties.

Optimal quality of knee implants is therefore an important issue, which is reflected in the revision rate. From an epidemiological point of view, the implantation rate (primary and revision) of artificial knee joints is expected to grow exponentially by up to 600% in the USA in 2030 (Kurtz et al. 2007). In absolute figures, the number of total knee implants has increased in OECD countries by 42% from 2005 to 2011, with annual growth rates of up to 20% (OECD 2013). Revisions account for over 20% of all knee replacements in Australia, Germany, and Austria, which is equivalent to 20–28 per 105 inhabitants (Falbrede et al. 2011, NJRA 2012). The revision rate calculated from registries has been 6% for total knee arthroplasty (TKA) and 17% for unicondylar knee arthroplasty (UKA) at 10 years (Pabinger et al. 2012).

Non-registry studies are considered to be the main evaluation tool for market approval, post-market surveillance, and quality assessment of joint replacements after market introduction in the early days, since registry data are not commonly available. However, there have been significant flaws regarding the reproducability of non-registry studies (No_authors_listed 2008, Labek et al. 2010).

We therefore wanted to assess the time interval between market introduction of knee implants and emergence of reliable outcome data. We defined reliability as compliance of revision rate between non-registry studies and registry studies. To our knowledge, there have been no reports in the literature comparing non-registry studies of specific products and assessing revision rates spanning a period of over 40 years after market introduction. Our hypothesis was that for the majority of implants, studies with revision rates would be available and that the data would be reliable.

Methods

Study sample

Using PubMed, Embase, Cochrane, and Medline, a systematic review of the medical literature in indexed peer-reviewed journals was done using the following search terms: “prosthesis/es”, “implants”, “joint prosthesis/es” and “arthroplasty/ies”. Articles were evaluated in full text by at least 2 independent reviewers, and their results were cross-checked by an independent reviewer who was blind regarding their results and revision rates. Studies were included if they contained “revision for any cause”. We excluded case studies and studies that focused solely on a specific reason for the revision (e.g. re-revision, mechanical failure, infection, or aseptic loosening). A detailed PRISMA statement and the outcomes of the individual knee prostheses have been published (Pabinger et al 2012). We compared the above non-registry studies with the highest value registry reports type A.1.1.1.1. (Labek et al. 2011c). Data collection in these registries had to be performed for the specific purpose of evaluation, coverage had to be nationwide, data had to be comprehensive, and conformity of data sets for assessment had to be representative. The following national arthroplasty registries contained the relevant knee implants (AGC, Kinemax, PFC, LCS, Oxford uni, and LINK uni): the Australian Joint Replacement Register (https://aoanjrr.dmac.adelaide.edu.au), the Danish Knee Arthroplasty Register (https://www.knee.dk/groups/grp_login.php), the Finnish National Arthroplasty Register (http://www.nam.fi/english/publications/), the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register (http://nrlweb.ihelse.net/eng/), the New Zealand Joint Register (http://www.cdhb.govt.nz/njr/), and the Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register (http://www.knee.nko.se/english/online/thePages/contact.php).

Study design

The following parameters were assessed: author, publication year, year of market introduction, type of prosthesis, number of primary cases, follow-up (in years) of patients in each study, follow-up (in years) after market introduction for each implant, number of revisions, and/or revision rate.

To normalize separate studies with different follow-up and numbers of implants, we used “revision rate per 100 observed component years” (“rev/100comp”), which is a descriptive epidemiological parameter comparable to “pack years” in tobacco smoking (Doll and Hill 1956, Hill and Doll 1956, Labek et al. 2011c). The component years are calculated as follows:

component years = no. of cases × no. of years

A value of 1 revision per 100 observed component years corresponded to a revision rate of 1% at 1 year and a 10% revision rate at 10 years in a linear function (Labek et al. 2011). This allows comparison across studies with a different follow-up and varying number of cases:

revisions per 100 observed component years = no. of revisions × 100 / (no. of cases × follow-up in years).

Statistics

The data of the non-registry studies were sorted by years after market introduction and data from the same year were pooled. A weighted revision rate per year and 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated from the first studies in 1978 up to 2011 for each prosthesis, and for all TKAs and UKAs combined. The number of revisions and the observed component years of individual studies were calculated to obtain the “revisions per 100 observed component years” after market introduction, which gave the weighted revision rate per 100 observed component years of all non-registry studies published after market introduction.

Registry data were pooled, and a weighted revision rate per 100 observed component years was calculated in the same way. Registry data were taken from the last decade, because there were comparatively few previous data. Thus, registry data are shown as a horizontal line and not according to year.

As found in the Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register, the maximum deviation in revision rates matching every hospital against the national mean rate did not exceed a ratio of 1.5–2 (SKAR 2012). Thus, deviations in revision rates between non-registry studies and registry studies (data) that exceeded a ratio of 2 were defined as statistically significant and relevant in order to identify confounders and bias of individual authors or local circumstances, such as surgical experience and infrastructural differences.

We excluded implants where all non-registry studies together revealed less than 100 revisions published in total, irrespective of the number of cases and revisions per study published. In order to avoid publication bias, we classified these series—and hence the respective implant—as too weak to be compared to registry data. Thus, we only addressed implants for which more than 100 revisions could be found in all non-registry studies together, irrespective of the number of cases and revisions per study. For 28 of the 34 knee implants assessed, no relevant number of revisions was published in non-registry studies. The following 6 implants (with year of market introduction) were included: TKA: AGC (1983), Kinemax (1988), PFC (1984), and LCS (1977). UKA: Oxford uni (1976) and LINK uni (1972).

Results

Number of non-registry studies with revision data

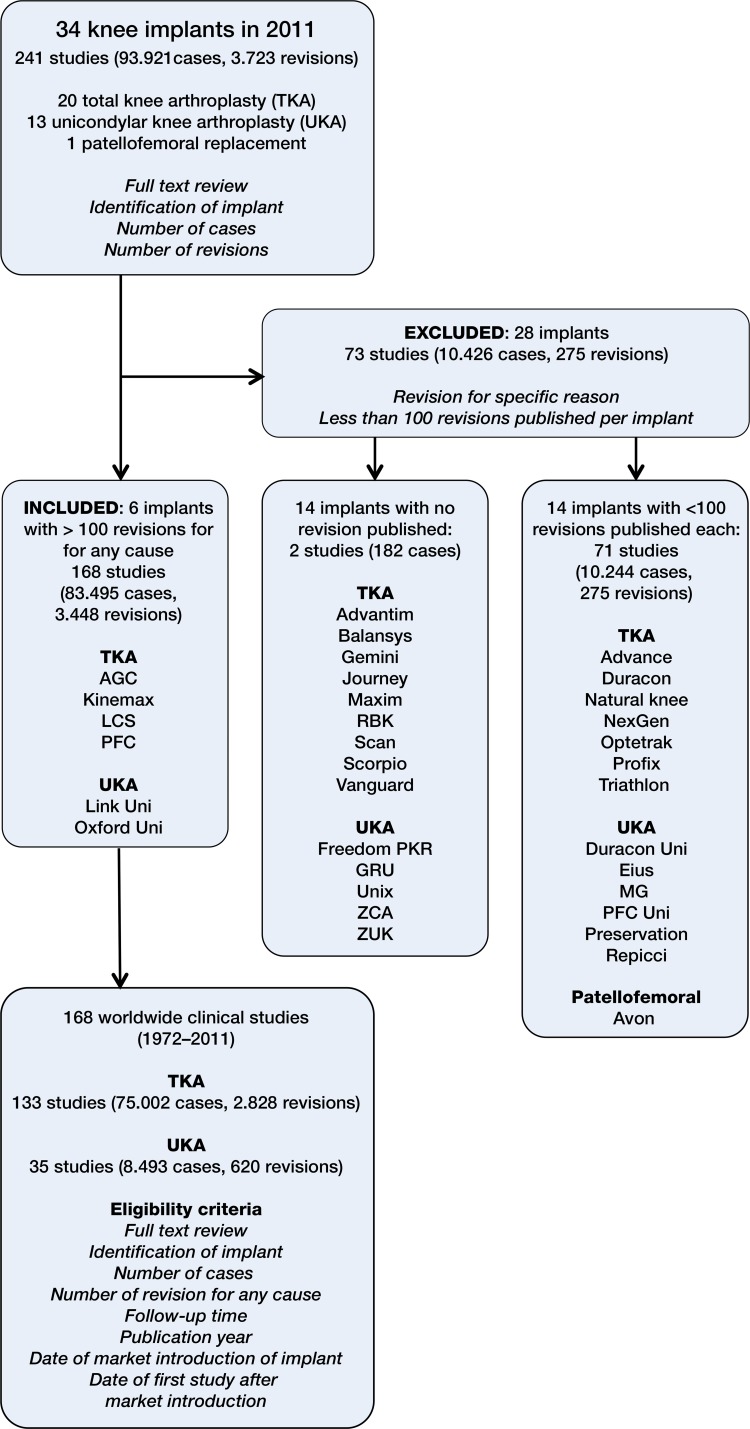

In total, 34 knee implants with registry data were found up to the year 2011, of which 28 (82%) had to be excluded, due to lack of revision data in non-registry studies (Figure 1). 14 implants had no revisions and 14 had less than 100 revisions published in non-registry studies (i.e. not related to registries). 6 implants remained for analysis (18%). These had featured in 168 non-registry studies (83,495 primary implants, 3,448 revisions, and 673,220 observed component years, 1972–2011) with a mean follow-up of 8.1 years (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Implant names and numbers of revisions published in non-registry studies.

Follow-up

The maximum follow-up after market introduction was 34 years for TKA and 39 years for UKA. The time to first publication related to a TKA was 6 years following market introduction and the corresponding time for UKA was 13 years. Half of all non-registry studies on TKA and UKA were published after 20 and 28 years. (Table).

Included non-registry studies on knee arthroplasty implants following market introduction

| Years after market introduction | All studies | TKA studies | UKA studies | Cases revised | Cases implanted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–10 | 8 | 8 | 0 | 45 | 1,350 |

| 11–20 | 69 | 58 | 11 | 1,136 | 35,383 |

| 21–30 | 84 | 67 | 17 | 1,992 | 44,796 |

| >31 | 7 | 0 | 7 | 275 | 1,966 |

| Total | 168 | 133 | 35 | 3,448 | 83,495 |

Publication times for revisions

Two-thirds of revisions were published after the second decade. The following percentages of revisions were published in non-registry studies after market introduction: 1% (45/3,448), 33% (1,136/3,448), 58% (1,992/3,448), and 8% (275/3,448) in the first, second, third and fourth decade, respectively (Table).

The pooled data for the 6 different implants analyzed from the national registries involved 690,443 observed component years (161,015 primary implants and 4,880 revisions). Based on these data, the mean rate of revision after TKA was 0.6 rev/100comp, whereas the mean rate of UKA was 1.7 rev/100comp.

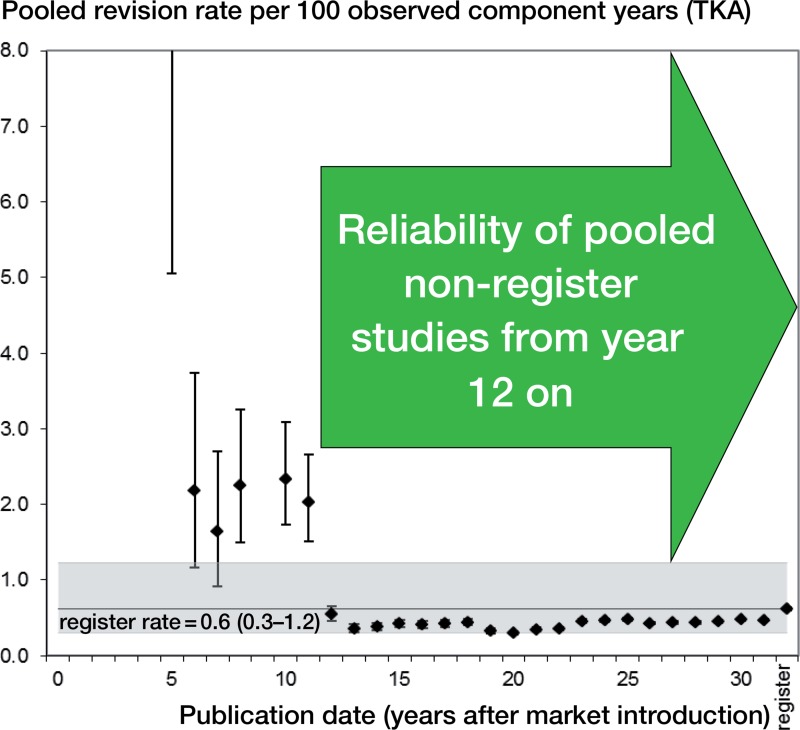

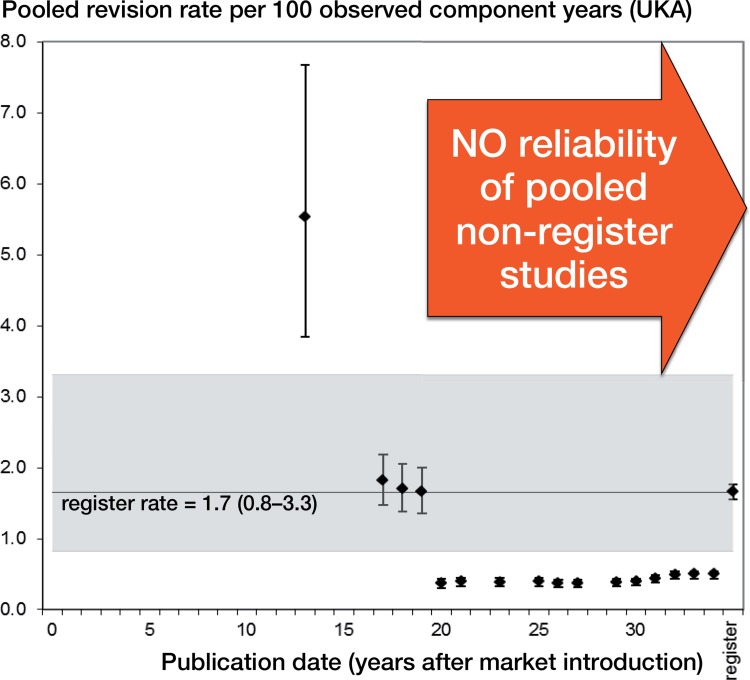

Revisions per 100 observed component years declined over time

Annual rev/100comp rates from pooled non-registry studies declined over time (Figures 2 and 3). In TKA (Figure 2), rev/100comp rates from non-registry studies were significantly higher than corresponding registry data in the first 12 years after market introduction, but were comparable thereafter. In UKA (Figure 3), we did not find any studies matching our inclusion criteria in the first decade. The first non-registry studies were published 13 years after market introduction. In the following years, the rev/100comp rates were comparable to the pooled registry data. From the second decade, the rev/100comp rates were statistically significantly lower than register data. This was also reflected in cumulative data of non-registry studies compared to registry data (clinical: mean 0.7 rev/100comp; registry: mean 1.7 rev/100comp). In contrast, mean revision rates per 100 observed component years of TKA were comparable in non-registry studies and registry data (0.5 and 0.6, respectively).

Figure 2.

Revision rate of total knee arthroplasty (TKA) following market introduction (all non-registry studies).

Figure 3.

Revision rate of unicondylar knee arthroplasty (UKA) following market introduction (all non-registry studies).

Confounders

We assessed sample size, duration, origin, and methodology of the individual non-registry studies. In terms of reliability, there was no superiority of studies with a larger sample size and longer duration as compared to smaller studies. In 5 of the 6 protheses, the developers reported a significantly lower revision rate than independent users (p < 0.01).

Discussion

For the majority (82%) of the 34 knee implants assessed, no relevant number of revisions was published in non-registry studies. Despite the existence of UKA for about 39 years and TKA for about 34 years, the poor number of non-registry studies with revision rates in general and the questionable reliability of UKA data was surprising. This highlights the importance of clinical registries for implantable devices, as stated by the EU Commission (EUROPEAN_COMMISSION 2012).

Comparison with other studies

The trend of revision rates decreasing over time can be explained in part by learning curve effects and technical improvements (Peltola et al. 2013). A similar effect was seen in the Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register for TKA, where for a recent 10-year period (2000–2009) the relative risk of revision was considerably lower than for a previous 10-year period (1987–1996) (SKAR 2012). However, this adjustment over time has not been seen for UKA in the last 4 decades. Although learning curve effects can contribute in part, publication bias from developers’ studies was also found, especially for UKA—as described previously (Labek et al. 2011b, Pabinger et al. 2012).

Our finding that UKA had a higher revision rate—by a factor of 3—than TKA confirmed the results of a previous publication (Labek et al. 2011b), and could in part be explained by a different patient population: UKAs were generally implanted in younger and more active patients. In the last decade, the mean age for implantation of UKA dropped from 70 to 62 years, while that for TKA only moved from 70 to 69 (SKAR 2012). From the point of view of this study, one can ask why knee implants with a worse revision rate were implanted in a younger group of patients. One can also speculate whether the overly positive results from developers in non-registry studies may also have contributed (Pabinger et al. 2012).

Regarding TKA, clinical data became available 6 years after market introduction, and they were comparable to registry data after year 12 and up to the present. Regarding UKA, clinical data were first available 13 years after market introduction, and with the exception of individual years, published revision rates in the decades thereafter were significantly lower than in registries. A 2-fold difference in revision rates between individual centers and developers of the relevant implant may be explained by confounding factors (e.g. surgical expertise, infrastructural differences, and so on), since this difference can also be found in different hospitals: The Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register compared the 10-year period 2000–2009 with the 10-year period 1987–1996 (SKAR 2012). The relative difference between the individual hospitals had not changed between the 2 periods and some units still had a 1.5–2 times higher or lower risk than the average unit. Thus, the reliability of revision rates of non-registry studies on UKA must be questioned.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The implants analyzed belong to the most common with regard to company size and studies published. Since we only focused on implants with at least 100 revisions published in all studies, we omitted implants from less prominent manufacturers. However, it can be assumed that implants with less publications would be even more difficult to assess in terms of reproducibility. Regarding UKA, due to the insufficient information in non-registry studies, it was not possible to pool age and sex and other confounding factors. One can imagine that the research populations regarding UKA are not comparable in registry studies and non-registry studies. Another simplification is that we compared the pooled annual number of revisions per 100 observed component years of all non-registry studies over 4 decades to a linear value derived from registry data for the last decade. However, especially in the first years after market introduction, it was not always possible to calculate an annual registry-derived revision rate for every implant, since registry data originated later. But even if we assume a logarithmic “learning curve” for the UKA registry rate, this would not change our results.

Conclusions

Regarding revision rate, for 82% of the different types of knee implants (TKA and UKA), data in non-registry studies were either absent or poor. Regarding UKA, the reliability of pooled revision rates extracted from non-registry studies must be questioned—from 1972 up to the present. The time interval needed to obtain reliable revision data from non-registry studies was 12 years for TKA and it was indefinite for UKA. Nowadays, registry data are therefore superior to non-registry data when assessing outcome and revision rate. Since many of the implants assessed are old, we recommend more active publication of data on new devices.

Acknowledgments

CP: study design, data collection, interpretation of data, and drafting and revision of the manuscript. DL and DC: revision of manuscript. AB: interpretation of data, statistics, and revision of manuscript. NB: data collection and revision of manuscript. GL: data acquisition and data analysis.

Data for this study have been derived in co-operation with the EUPHORIC project (funded by EU Commission DG SANCO, grant agreement 2003134). No benefits in any other form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

Additional data available at http:///www.ear.efort.org/.../E-Book_QoLA Project_Final Report_EFORT 2011.pdf

References

- Doll R, Hill AB. Lung cancer and other causes of death in relation to smoking; a second report on the mortality of British doctors . Br Med J. 1956;2(5001):1071–81. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5001.1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EUROPEAN_COMMISSION. Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on medical devices 2012 http://ec.europa.eu/health/medical-devices/files/revision_docs/proposal_2012_542_en.pdf . (last accessed June 9th, 2014)

- Falbrede I, Widmer M, Kurtz S, Schneidmuller D, Dudda M, Roder C. Utilization rates of lower extremity prostheses in Germany and Switzerland: A comparison of the years 2005-2008. Orthopaede. 2011;40(9):793–801. doi: 10.1007/s00132-011-1787-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godlee F. Serious risks from metal-on-metal hip implants. Br Med J. 2012;344:e1539. [Google Scholar]

- Hill AB, Doll R. Lung cancer and tobacco; the B.M.J.’s questions answered . Br Med J. 1956;1(4976):1160–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.4976.1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030 . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2007;89(4):780–5. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labek G, Pabinger C, et al. Quality of publications regarding the outcome of revision rate after arthroplasty. EFORT Booklet. 2010;1:1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Labek G, Neumann D, Agreiter M, Schuh R, Böhler M. Impact of implant developers on published outcome and reproducibility of cohort-based clinical studies in arthroplasty . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2011a;93(Suppl 3):55–61. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.01108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labek G, Sekyra K, Pawelka W, Janda W, Stockl B. Outcome and reproducibility of data concerning the Oxford unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: a structured literature review including arthroplasty registry data . Acta Orthop. 2011b;82(2):131–5. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2011.566134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labek G, Thaler M, Janda W, Agreiter M, Stockl B. Revision rates after total joint replacement: cumulative results from worldwide joint register datasets . J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2011c;93(3):293–7. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B3.25467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NJRA: National Joint Registery Australia Annual Report 2012 at https://aoanjrr.dmac.adelaide.edu.au. (last accessed June 9th, 2014)

- No_authors_listed. European Public Health Outcome Research and Indicators Collection (EUPHORIC) 2008 final report. http:/www.euphoric-project.eu/.../Euphoric_final-report_0.pdf. (last accessed June 9th, 2014)

- OECD Health Data 2013 ISSN: 2074-3963 (online) DOI: 10.1787/health-data-en. (last accessed June 9th, 2014)

- Pabinger C, Berghold A, Boehler N, Labek G. Revision rates after knee replacement. Cumulative results from worldwide clinical studies versus joint registers . Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2012;21(2013):263–8. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2012.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peltola M, Malmivaara A, Paavola M. Learning curve for new technology? A nationwide register-based study of 46,363 total knee arthroplasties . J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2013;95(23):2097–103. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SKAR Sundberg M, Lidgren L, W-Dahl A, Robertsson O. The Swedish Knee Arthoplasty Register. 2012. Changes in risk of revision over time. Relative risk of revision for hospitals 2001–2010. Swedish Knee Arthoplasty Register ANNUAL REPORT 2012 – PART II, page 41. 41. (last accessed June 9th, 2014) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Smith AJ, Dieppe P, Vernon K, Porter M, Blom AW. Failure rates of stemmed metal-on-metal hip replacements: analysis of data from the National Joint Registry of England and Wales . Lancet. 2012;379(9822):1199–204. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60353-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]