Abstract

Literature indicates an increased risk of suicide among women who have had cosmetic breast implants. An explanatory model for this association has not been established. Some studies conclude that women with cosmetic breast implants demonstrate some characteristics that are associated with increased suicide risk while others support that the breast augmentation protects from suicide. A systematic review including data collection from January 1961 up to February 2014 was conducted. The results were incorporated to pre-existing suicide risk models of the general population. A modified suicide risk model was created for the female cosmetic augmentation mammaplasty candidate. A 2-3 times increased suicide risk among women that undergo cosmetic breast augmentation has been identified. Breast augmentation patients show some characteristics that are associated with increased suicide risk. The majority of women reported high postoperative satisfaction. Recent research indicates that the Autoimmune syndrome induced by adjuvants and fibromyalgia syndrome are associated with silicone implantation. A thorough surgical, medical and psycho-social (psychiatric, family, reproductive, and occupational) history should be included in the preoperative assessment of women seeking to undergo cosmetic breast augmentation. Breast augmentation surgery can stimulate a systematic stress response and increase the risk of suicide. Each risk factor of suicide has poor predictive value when considered independently and can result in prediction errors. A clinical management model has been proposed considering the overlapping risk factors of women that undergo cosmetic breast augmentation with suicide.

Keywords: Cosmetic surgery, Silicone, Breast implants, Mammaplasty, Suicide

INTRODUCTION

According to the National Institute of Mental Health in the US, suicide is a major, preventable public health problem as the tenth leading cause of death, accounting for 34,598 deaths per annum [1,2]. With an overall rate of 11.3 suicide deaths per 100,000 people and an estimated 11 attempted suicides per actual suicide death [1,2]. Recent research indicates an increased risk of suicide among women who have had cosmetic breast implants [3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. This unanticipated finding has caused a conflict regarding the safety of cosmetic breast augmentation and has led to several empirical explanations [10,11].

Among them the specific characteristics of women who have had cosmetic breast implants and their association with raised suicide risk has been encountered as a reasonable explanation while others support that the breast augmentation confer protection from suicide [10,11,12,13,14,15]. McLaughlin et al. [12] recommended further epidemiological studies in order to identify whether or not there is a causal relationship between breast implantation and suicide and large-scale retrospective cohort studies to compare the suicide risk in women with and without implants. Joiner [13] estimated that the suicide risk in women with cosmetic breast augmentation should be four times greater than the general population's rate and concluded that the cosmetic augmentation operation may suppress suicidality.

The current challenge is to demonstrate an explanatory model and identify specific predisposing suicide risk factors in those women. The aim of this article is to review the literature regarding the characteristics of women who have had cosmetic breast implants that could be associated with increased suicide risk and to attempt to devise a conceptualized suicide risk model for the women candidates of cosmetic breast augmentation. Before discussing that it is necessary to review the studies that investigate the association between cosmetic breast augmentation and suicide risk.

METHODS

A systematic review [16,17,18,19,20] was conducted investigating the association between cosmetic breast augmentation and suicide risk and the characteristics of the breast augmentation female patient and their relation with suicide. Our data collection period was from January 1961 until February 2014. The review included prospect cohort studies, retrospective cohort studies, randomized clinical trials, case-control studies clinical trials and excluded systematic reviews.

Our review grouped the identified studies in 3 different categories based on their investigation subject: 1) Epidemiological studies that were investigating the relationship between cosmetic breast augmentation and suicide in women; 2) Studies that evaluated the psychosocial and psychological status both before and after breast augmentation procedures were grouped together; 3) Epidemiological studies that were focusing on psychiatric history, demographic characteristics, life-style characteristics and reproductive history of women with cosmetic breast implants.

We excluded studies that evaluated the usage of breast implants for reconstructive purposes, studies that evaluated general cosmetic surgery rather than cosmetic breast augmentation and studies that included breast augmentation in men. Database was collected from: PubMed, MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Web of Science, OvidSP, ScienceDirect, JAMA Psychiatry, with the keywords: Cosmetic surgery, Suicide and/or predictor factors, Silicone breast implants/breast augmentation and/or self-esteem, Body image, Psychosocial outcomes. Further studies were yielded from the reference lists used in the identified articles. After exporting the data, we evaluated them based on the scientific question and exclusion criteria. Evaluation of each result separately was followed and studies were organized according to the degree of similarity among them and reference tables were created. The results were incorporated to pre-existing suicide risk models of the general population and a modified suicide risk model was created for the female cosmetic augmentation mammaplasty candidate.

RESULTS

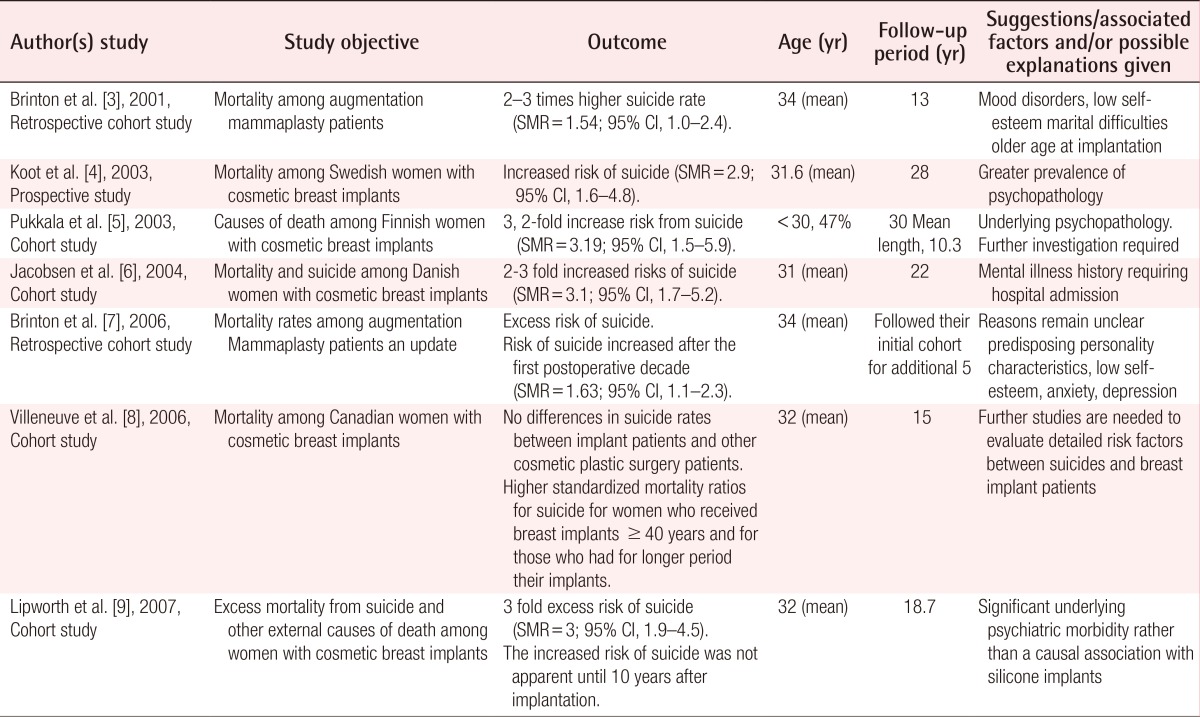

Our literature search identified 7 epidemiological cohort studies addressing the issue of cosmetic breast augmentation and suicide, which are presented in chronological order in Table 1 [3,4,5,6,7,8,9].

Table 1. Suicide in women with cosmetic breast implants.

SMR, standardized mortality ratio; CI, confidence interval.

This demonstrates available data such as the follow up period, the age and the outcome after cosmetic breast augmentation. Among these studies, only Villeneuve et al. [8] didn't find any relationship between cosmetic breast augmentation and high risk of suicide. The other studies found a two to three fold increased risk of suicide in women with cosmetic augmentation implants compared to the general population. Three of the studies [7,8,9], suggest that the rate of suicide is higher in women who underwent breast augmentation after the age of 40 and for women who had their implants for longer period of time (>than 10 years). Several proposed explanations for this association include the higher prevalence of psychopathology [4], mental illness history that required hospital treatment [6] and significant underlying psychiatric morbidity in the above groups [9]. The non prospective study design with regards to the association between suicide and cosmetic breast implants limits any definitive conclusions on causality in this relationship [15].

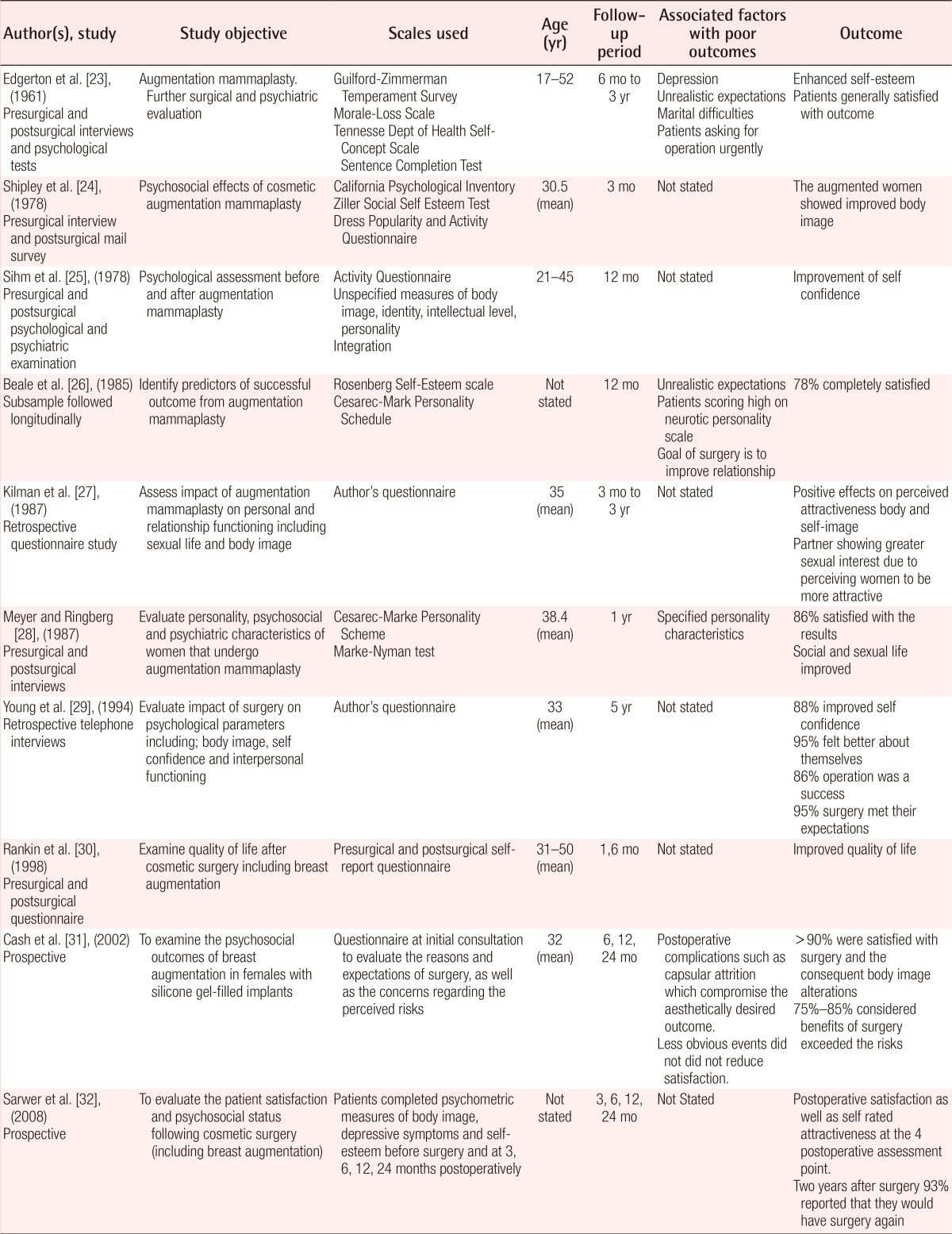

The impact of patients postoperative expectations and the level of postoperative satisfaction, have been associated with poor psychosocial outcomes that could potentially relate with the increased rate of suicides among cosmetic breast augmentation patients [21,22]. Ten studies focusing on the psychosocial outcomes (self-esteem, body-image, postoperative satisfaction, quality of life) of women with breast augmentation were included for our current review (Table 2) [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32].

Table 2. Psychosocial outcomes/psychological characteristics.

In summary the majority of women reported high postoperative satisfaction and some of them would have surgery again [21]. Beale et al. [26] using the Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale and the Cesarec-Mark personality Schedule for a 12 months follow up period tried to assess the predictors of successful outcome from augmentation mammaplasty and concluded that 78% of women were completely satisfied. They also resulted that patients with unrealistic expectations and psychiatric problems are more likely to be related with poor outcome such as low self-esteem [26]. Kilman et al. [27] concluded that breast mammaplasty enhances body image and increases sexual interest of the patient's partner. Meyer and Ringberg [28], assessed the personality, the psychosocial and psychiatric characteristics of those women and concluded that 86% were satisfied and that their social and psychological expectations had been fulfilled [28]. Young et al. [29] reported postoperative increased self confidence among 88% of the women and 95% postoperative rates of satisfaction. Cash et al. [31] found that more than 90% of women were satisfied with the outcome and attained expectations of enhanced body image. The above studies demonstrate that the postoperative outcome is unlikely to contribute to the increased suicide risk among those women.

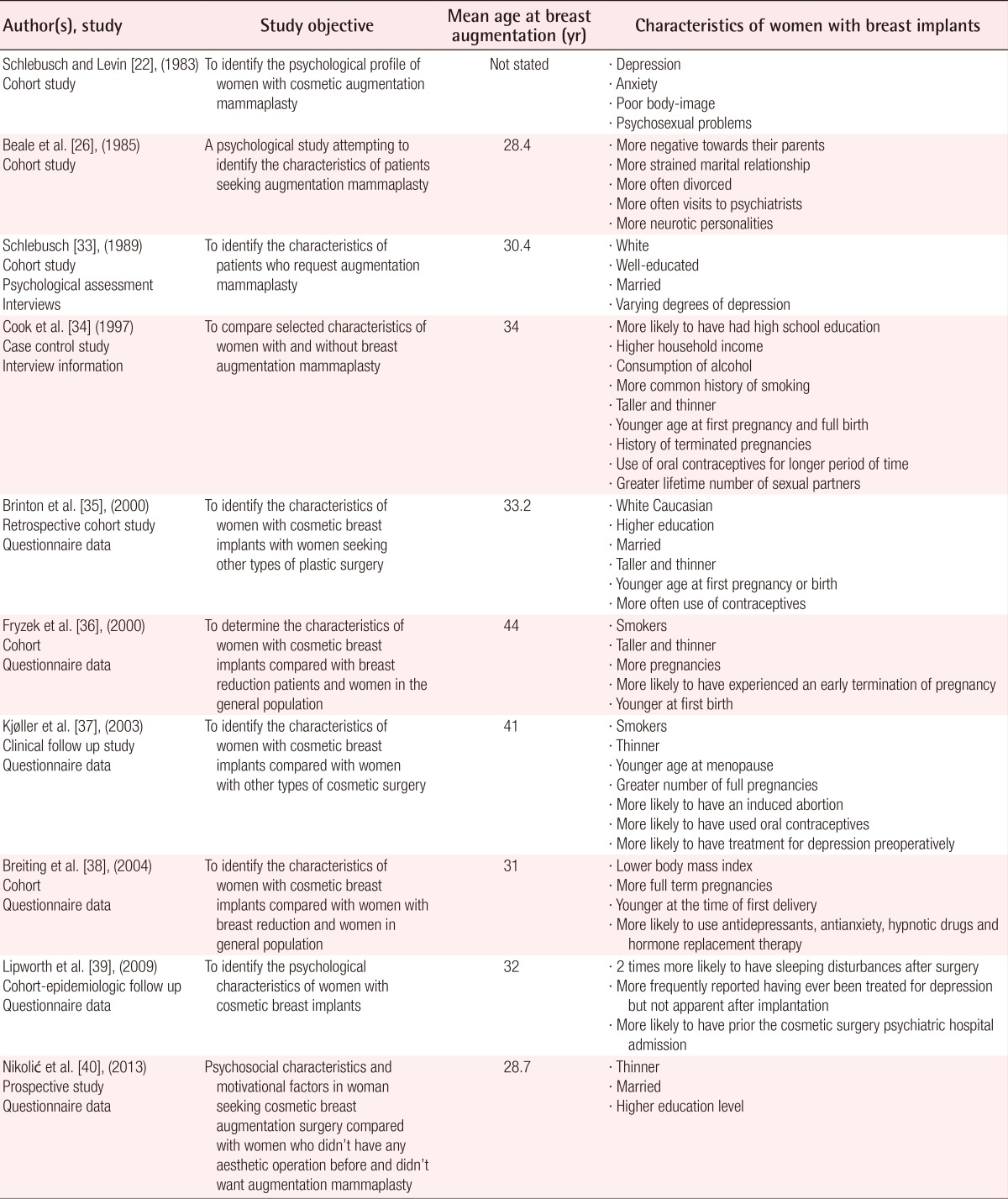

The specific characteristics of women that undergo cosmetic breast augmentation have been assumed to be linked with the increased suicide risk of this population [15,21]. Several researchers have conducted studies in order to identify characteristics (demographic, lifestyle, psychiatric and reproductive history) of women with cosmetic breast implants. 10 studies were identified as demonstrated in Table 3 in chronological order [22,26,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40].

Table 3. Other characteristics (demographic/lifestyle/psychiatric/reproductive history).

Most studies agree that the typical breast augmentation female patient [34,35,36,37,38,39] is more often, Caucasian, between 28 to 44 years of age, thin and tall, smoker, consuming alcohol, with good education backgrounds [33,34,35,37,40] and likely to have history of depression, anxiety and neurotic personality. They seek for psychiatric consultations more often than the general population and have increased rate of psychiatric hospital admissions prior to the cosmetic surgery [22,26,37,38,39,40]. Regarding their reproductive history they have younger age at menopause, greater number of full pregnancies and are more likely to have had an induced abortion [34,36,37]. Studies remain inconclusive regarding their marital status [26,33,35,40].

DISCUSSION

Women who have had cosmetic breast implants postoperatively report high overall satisfaction and experience good outcomes in psychological and psychosocial terms (Table 2) [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. These benefits can be compromised due to postoperative complications such as infection, pain, hematoma, silicone implant hemorrhage, capsular contracture and loss of nipple sensation [41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49]. Complications and unreasonable expectations from the operation could contribute to affective disorders and impair the quality of life although this association has not been studied adequately [31].

According to the National Institute of Mental Health in the United States [2,50] risk factors for suicide in general population are:

Current ideation, intent, plan, access to means

Previous suicide attempt or attempts

Alcohol/Substance abuse

Current or previous history of psychiatric diagnosis

Impulsivity and poor self control

Hopelessness-presence, duration, severity

Recent losses-physical, financial, personal

Recent discharge from an inpatient psychiatric unit

Family history of suicide

History of abuse (physical, sexual or emotional)

Co-morbid health problems, a new diagnosis or worsening symptoms

Age, gender, race (elderly or young adult, unmarried, white, male, lives alone)

Same-sex sexual orientation

Pregnant women [51], having a child of less than 2-year-old [52] has been associated with lower suicidal risk. On the contrary, women of age range 35-44 years [53], unmarried, divorced or single women without strong social support and occupational instability [53,54,55,56] have increased suicide risk. Miscarriage has also been linked to an increased maternal suicide risk especially when induced [57,58,59,60]. Less studied dimensions that might be related to suicide in the female population are: living in urban areas [2,50,61] infertility [62,63], the familial clustering of suicidal behaviors and chronic physical illness [64,65,66]. The overlapping characteristics among the general population and the female cosmetic breast implant patient that constitute predisposal factors for suicide according to this study are: alcohol consumption, history of psychiatric diagnosis and admission to psychiatric unit, relationship problems, patient's age, Caucasian race and reproductive history.

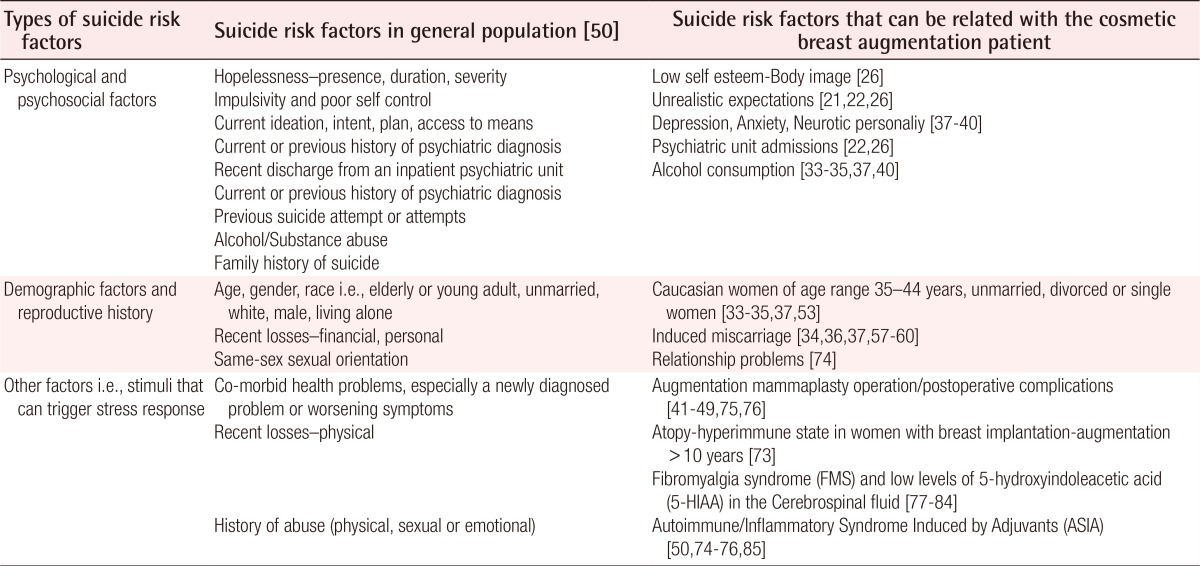

Silicone implants have been associated with the development of autoimmune diseases such as scleroderma, systematic erythematic lupus, mixed disorders of the connective tissue, rheumatoid arthritis and Sjögren's syndrome but this findings remain debatable [67,68,69,70,71]. More interestingly the implant explantation results in symptoms remission [72,73]. Less studied dimensions that could be related with the implant and it's potential contribution to suicide risk are the autoimmune syndrome induced by adjuvants (ASIA) and fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) (Table 4).

Table 4. Suicide risk factors.

Maijers et al. [73] conducted a descriptive cohort study investigating 80 women with silicone breast implants and unexplained systemic symptoms (fatigue, arthralgia, myalgia and cognitive symptoms). Most women had pre-existent allergies and the majority of them (89%) had silicone for cosmetic reasons. The median exposure time to the silicone implant was 14.5 years and most women did not have any past medical history. The authors [73] resulted that all women had the typical clinical manifestations of ASIA (i.e., fatigue, night sweats, morning stiffness, joint and muscle pain, dermatological manifestations). Explantation of the implants was showed to reduce the symptoms. Maijers et al. [73], concluded that silicone breast implants may cause systemic symptoms in women with hyperimmune state or atopy. They suggested that this is line with intolerance to silicone. The authors highlighted that the probable association between the silicone breast implants and unexplained systemic symptoms should be taken seriously but acknowledged that strong associations between silicone implants and connective tissue diseases have not been demonstrated [73,86,87,88,89,90].

Furthermore silicone is often associated as one of the possible causes of FMS [91,92,93], an idiopathic, yet common chronic condition characterized by widespread musculoskeletal pain [93]. Stisi et al. [77], reviewed the literature in an attempt to determine pathoaetiological mechanisms of FMS and found, that patients with FMS have decreased levels of 5-Hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) a serotonin metabolite in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). This finding is significant because decreased levels of 5-HIAA in CSF has been identified as a possible suicide risk predictor in several independent studies [77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84].

In summary the current literature highlights the importance of preoperative psychiatric screening with particular interest in any previous psychiatric admissions and in current or previous mental disorders such as depression. The reason of the increased suicide risk among women with cosmetic breast augmentation remains unclear [13,14] and further well designed epidemiological research is necessary.

Recently in the study of Overholser et al. [74] who investigated 148 individuals who died from suicide compared to adults who died from medical problems or accidents using psychological autopsy to assess Axis I psychiatric diagnosis concluded that a thorough evaluation of psychiatric diagnosis (i.e., depression), recent stressful life events (e.g., relationship, financial, work issues) and demographic characteristics are mandatory fields to be completed in every proper suicide risk assessment. These authors created a suicide risk model by conceptualizing the combination of demographic factors, psychiatric symptoms and recent stressful events highlighting the significance of the interactions between the variables. Moreover, they suggested that each demographic predictor on itself (e.g., unmarried, age) is not precise and results in false positive prediction errors. However they concluded that the identification of high suicide risk groups is not unrealistic and it can play an important role in the prevention of suicide if a holistic approach is taken into account especially with regards to stressful life events and precipitating factors. In the current literature addressing the issue of cosmetic breast augmentation and suicide, emphasis has been given to the importance of psychiatric history and demographic factors like independent variables associated with higher suicide risk.

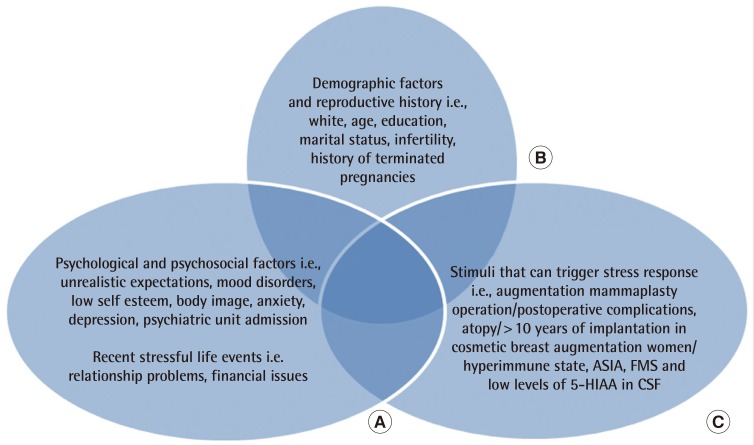

Taking into account the recent studies of Overholser et al. [74], Maijers et al. [73], Stisi et al. [77], and from our systematic review (Tables 1,2,3), we have synthesized Fig. 1 below.

Fig. 1. Suicide risk model.

(A) Psychological and psychosocial factors i.e.,unrealistic expectations, mood disorders, low self esteem, body image, anxiety, depression, psychiatric unit admission, recent stressful life events, relationship problems, financial issues. (B) Demographic factors and reproductive history i.e.,white, age, education, marital status, infertility, history of terminated pregnancies. (C) Stimuli that can trigger stress response i.e., augmentation mammaplasty operation/postoperative complications, atopy/>10 years of implantation in cosmetic breast augmentation women/hyperimmune state, ASIA, FMS, and low levels of 5-HIAA in CSF. ASIA, autoimmune syndrome induced by adjuvants; FMS, fibromyalgia syndrome; 5-HIAA, 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

The above suicide risk model includes three interacting ellipses and each of them contains independent risk suicide variables. The model is specific for women seeking augmentation mammaplasty because it synthesizes the combination of suicide predictors in general population and incorporates the specific independent risk factors for suicide that are encountered in the cosmetic breast augmentation candidate (i.e., unrealistic expectations, postoperative complications). It includes the factors of atopy/hyperimmune state and low levels of 5-HIAA which is considered to be related with the development of ASIA syndrome and FMS respectively. Although it remains disputable, ASIA particularly in women with pre-existing allergies cannot be excluded from being an independent risk factor associated with the implant that can increase the risk of suicide in terms of being a stressful life event and a chronic physical illness, both risk factors for suicide [2,50,74,75,76,85].

CONCLUSION

Suicide prediction is a complex task. A combination of demographic variables, psychiatric history, social, biological and other factors must be evaluated individually and in the context of the patient's whole environment. Women with underlying psychopathology, especially depression requiring previous hospital admission, medical history of terminated pregnancies should be considered high risk for suicide. Recent life stressors (financial, relationship or other personal issues) [74] that are not always part of a typical medical history might be important in predicting suicide risk and should be included in preoperative patient assessment. Breast augmentation surgery can stimulate a systematic stress response in several ways [41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,75,76] and increase the pre-existing risk of suicide in women who seek cosmetic mammaplasty. ASIA particularly in women with pre-existing allergies and FMS cannot be excluded from being independent risk factors. Each risk factor of suicide (i.e., unmarried, age, depression) has poor predictive value when considered independently and can result in false positive prediction errors. The suicide risk model we devise with interacting ellipses could be a helpful tool for plastic surgeons daily practice.

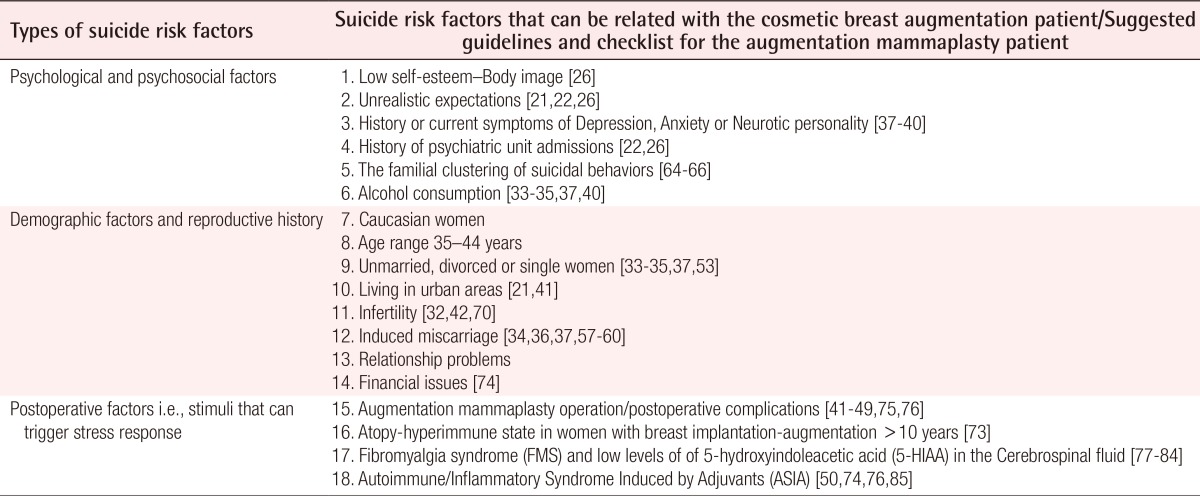

Our review concludes that there is 2 to 3 fold increased suicide risk among patients with augmentation mammaplasty. Although it remains unclear whether or not the augmentation mammaplasty operation can act as a trigger factor of suicide, it is more clear that women candidates have various degree of underlying psychopathology, demographic and psychosocial factors that are strongly related with increased suicide risk preoperatively. From this review no strong evidence that relates the augmentation mammaplasty operation itself with increased suicide risk occurs. ASIA and FMS syndrome despite being linked with systematic stress response which constitutes a suicide risk factor, do not cause increased suicide risk directly based on the existing evidence. It has not been excluded that factors such as: the operation itself, FMS, ASIA syndrome and >10 years of implantation in women with hyperimmune state can affect the suicide risk of the mammaplasty patient postoperatively. However this requires further exploration. Our research concludes that there are overlapping risk factors to the breast augmentation candidate that can predispose to suicide (Table 4). The plastic surgeon needs to be aware of those factors and attempt to detect them preoperatively and postoperatively. We created a pre and postoperative check list in an attempt to screen the mammaplasty patient in relation to suicide risk (Table 5).

Table 5. Summarized risk factors.

It should be noted 10,2% of suicides do not have any of the suicide risk factors according to the study by Overholser et al. [74] This disconcerting observation should draw our attention to the fact that although doctors can always attempt to assess the risk for suicide they are unable to predict it with complete accuracy.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.National Institutes of Health. Statistics [Internet] Rockville: National Institute of Mental Health; [cited 2014 Jul 28]. Available from: http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/suicide-in-the-us-statistics-and-prevention/index.shtml#risk. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Injury prevention & control: data & statistics [Internet] Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2014. [cited 2014 Jul 28]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brinton LA, Lubin JH, Burich MC, et al. Mortality among augmentation mammoplasty patients. Epidemiology. 2001;12:321–326. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200105000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koot VC, Peeters PH, Granath F, et al. Total and cause specific mortality among Swedish women with cosmetic breast implants: prospective study. BMJ. 2003;326:527–528. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7388.527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pukkala E, Kulmala I, Hovi SL, et al. Causes of death among Finnish women with cosmetic breast implants, 1971-2001. Ann Plast Surg. 2003;51:339–342. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000080407.97677.A5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacobsen PH, Holmich LR, McLaughlin JK, et al. Mortality and suicide among Danish women with cosmetic breast implants. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:2450–2455. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.22.2450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brinton LA, Lubin JH, Murray MC, et al. Mortality rates among augmentation mammoplasty patients: an update. Epidemiology. 2006;17:162–169. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000197056.84629.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Villeneuve PJ, Holowaty EJ, Brisson J, et al. Mortality among Canadian women with cosmetic breast implants. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164:334–341. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lipworth L, Nyren O, Ye W, et al. Excess mortality from suicide and other external causes of death among women with cosmetic breast implants. Ann Plast Surg. 2007;59:119–123. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e318052ac50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morgan E. Suicide after breast augmentation. Epidemiology. 2008;19:520–521. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31816b6a67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sher L. Cosmetic breast implants and suicide. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114:601–602. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000128496.36215.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McLaughlin JK, Lipworth L, Tarone RE. Suicide among women with cosmetic breast implants: a review of the epidemiologic evidence. J Long Term Eff Med Implants. 2003;13:445–450. doi: 10.1615/jlongtermeffmedimplants.v13.i6.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joiner TE., Jr Does breast augmentation confer risk of or protection from suicide? Aesthet Surg J. 2003;23:370–375. doi: 10.1016/S1090-820X(03)00213-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crerand CE, Infield AL, Sarwer DB. Psychological considerations in cosmetic breast augmentation. Plast Surg Nurs. 2009;29:49–57. doi: 10.1097/01.PSN.0000347725.13404.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sarwer DB, Brown GK, Evans DL. Cosmetic breast augmentation and suicide. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1006–1013. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.7.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The Cochrane Collaboration [Internet] Oxford: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2014. [cited 2014 Jul 28]. Available from: http://www.cochrane.org/cochrane-reviews. [Google Scholar]

- 17.PRISMA statement [Internet] 2014. [cited 2014 Jul 28]. Available from: http://www.prisma-statement.org/statement.htm.

- 18.Oxman AD. Checklists for review articles. BMJ. 1994;309:648–651. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6955.648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Littell JH, Corcoran J, Pillai VK. Systematic reviews and meta-analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins JP, Green S Cochrane Collaboration. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.McLaughlin JK, Wise TN, Lipworth L. Increased risk of suicide among patients with breast implants: do the epidemiologic data support psychiatric consultation? Psychosomatics. 2004;45:277–280. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.45.4.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schlebusch L, Levin A. A psychological profile of women selected for augmentation mammaplasty. S Afr Med J. 1983;64:481–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Edgerton MT, Meyer E, Jacobson WE. Augmentation mammaplasty. II. Further surgical and psychiatric evaluation. Plast Reconstr Surg Transplant Bull. 1961;27:279–302. doi: 10.1097/00006534-196103000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shipley RH, O'Donnel JM, Bader KF. Psychosocial effects of cosmetic augmentation mammaplasty. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1978;2:429–434. doi: 10.1007/BF01577982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sihm F, Jagd M, Pers M. Psychological assessment before and after augmentation mammaplasty. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg. 1978;12:295–298. doi: 10.3109/02844317809013009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beale S, Hambert G, Lisper HO, et al. Augmentation mammaplasty: the surgical and psychological effects of the operation and prediction of the result. Ann Plast Surg. 1985;14:473–493. doi: 10.1097/00000637-198506000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kilmann PR, Sattler JI, Taylor J. The impact of augmentation mammaplasty: a follow-up study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1987;80:374–378. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198709000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meyer L, Ringberg A. Augmentation mammaplasty--psychiatric and psychosocial characteristics and outcome in a group of Swedish women. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 1987;21:199–208. doi: 10.3109/02844318709078100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Young VL, Nemecek JR, Nemecek DA. The efficacy of breast augmentation: breast size increase, patient satisfaction, and psychological effects. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;94:958–969. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199412000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rankin M, Borah GL, Perry AW, et al. Quality-of-life outcomes after cosmetic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102:2139–2145. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199811000-00053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cash TF, Duel LA, Perkins LL. Women's psychosocial outcomes of breast augmentation with silicone gel-filled implants: a 2-year prospective study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109:2112–2121. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200205000-00049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sarwer DB, Infield AL, Baker JL, et al. Two-year results of a prospective, multi-site investigation of patient satisfaction and psychosocial status following cosmetic surgery. Aesthet Surg J. 2008;28:245–250. doi: 10.1016/j.asj.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schlebusch L. Negative bodily experience and prevalence of depression in patients who request augmentation mammoplasty. S Afr Med J. 1989;75:323–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cook LS, Daling JR, Voigt LF, et al. Characteristics of women with and without breast augmentation. JAMA. 1997;277:1612–1617. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brinton LA, Brown SL, Colton T, et al. Characteristics of a population of women with breast implants compared with women seeking other types of plastic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:919–927. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200003000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fryzek JP, Weiderpass E, Signorello LB, et al. Characteristics of women with cosmetic breast augmentation surgery compared with breast reduction surgery patients and women in the general population of Sweden. Ann Plast Surg. 2000;45:349–356. doi: 10.1097/00000637-200045040-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kjoller K, Holmich LR, Fryzek JP, et al. Characteristics of women with cosmetic breast implants compared with women with other types of cosmetic surgery and population-based controls in Denmark. Ann Plast Surg. 2003;50:6–12. doi: 10.1097/00000637-200301000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Breiting VB, Holmich LR, Brandt B, et al. Long-term health status of Danish women with silicone breast implants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114:217–226. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000128823.77637.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lipworth L, Kjoller K, Holmich LR, et al. Psychological characteristics of Danish women with cosmetic breast implants. Ann Plast Surg. 2009;63:11–14. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3181857318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nikolic J, Janjic Z, Marinkovic M, et al. Psychosocial characteristics and motivational factors in woman seeking cosmetic breast augmentation surgery. Vojnosanit Pregl. 2013;70:940–946. doi: 10.2298/vsp1310940n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bondurant S, Ernster VL, Herdman R, et al. Safety of silicone breast implants. Washington, D.C.: Institute of Medicine; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 42.McGrath MH, Burkhardt BR. The safety and efficacy of breast implants for augmentation mammaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984;74:550–560. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198410000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barton FF, Tebbetts JB. Augmentation mammaplasty. Sel Read Plast Surg. 1989;5:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brandt B, Breiting V, Christensen L, et al. Five years experience of breast augmentation using silicone gel prostheses with emphasis on capsule shrinkage. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984;18:311–316. doi: 10.3109/02844318409052856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Winding O, Christensen L, Thomsen JL, et al. Silicon in human breast tissue surrounding silicone gel prostheses. A scanning electron microscopy and energy dispersive X-ray investigation of normal, fibrocystic and peri-prosthetic breast tissue. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 1988;22:127–130. doi: 10.3109/02844318809072383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rudolph R, Abraham J, Vecchione T, et al. Myofibroblasts and free silicon around breast implants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1978;62:185–196. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197808000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Argenta LC. Migration of silicone gel into breast parenchyma following mammary prosthesis rupture. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1983;7:253–254. doi: 10.1007/BF01570670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eisenberg HV, Bartels RJ. Rupture of a silicone bag-gel breast implant by closed compression capsulotomy: case report. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1977;59:849–850. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197706000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang TT, Blackwell SJ, Lewis SR. Migration of silicone gel after the "squeeze technique" to rupture a contracted breast capsule. Case report. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1978;61:277–280. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197802000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.National Institute of Mental Health. Suicide in America: frequently asked questions [Internet] Rockville: National Institute of Mental Health; [cited 2014 Jul 28]. Available from: http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/suicide-in-america/index.shtml. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hawton K, Harriss L. The changing gender ratio in occurrence of deliberate self-harm across the lifecycle. Crisis. 2008;29:4–10. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910.29.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Qin P, Agerbo E, Westergard-Nielsen N, et al. Gender differences in risk factors for suicide in Denmark. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:546–550. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.6.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.White A, Holmes M. Patterns of mortality across 44 countries among men and women aged 15-44 years. J Mens Health. 2006;3:139–151. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Palladino CL, Singh V, Campbell J, et al. Homicide and suicide during the perinatal period: findings from the National Violent Death Reporting System. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:1056–1063. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31823294da. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Samandari G, Martin SL, Kupper LL, et al. Are pregnant and postpartum women: at increased risk for violent death? Suicide and homicide findings from North Carolina. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15:660–669. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0623-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Murray D, Cox JL, Chapman G, et al. Childbirth: life event or start of a long-term difficulty? Further data from the Stoke-on-Trent controlled study of postnatal depression. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;166:595–600. doi: 10.1192/bjp.166.5.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gissler M, Hemminki E, Lonnqvist J. Suicides after pregnancy in Finland, 1987-94: register linkage study. BMJ. 1996;313:1431–1434. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7070.1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gissler M, Berg C, Bouvier-Colle MH, et al. Injury deaths, suicides and homicides associated with pregnancy, Finland 1987-2000. Eur J Public Health. 2005;15:459–463. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cki042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Steinberg JR, Becker D, Henderson JT. Does the outcome of a first pregnancy predict depression, suicidal ideation, or lower self-esteem? Data from the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2011;81:193–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2011.01088.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Morgan CL, Evans M, Peters JR. Suicides after pregnancy. Mental health may deteriorate as a direct effect of induced abortion. BMJ. 1997;314:902. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thorslund J. Ungdomsselvmord og moderniseringsproblemer blandt Inuit i Grønland [dissertation] Holte: SocPol; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kjaer TK, Jensen A, Dalton SO, et al. Suicide in Danish women evaluated for fertility problems. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:2401–2407. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.da Silva RA, da Costa Ores L, Jansen K, et al. Suicidality and associated factors in pregnant women in Brazil. Community Ment Health J. 2012;48:392–395. doi: 10.1007/s10597-012-9495-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brent DA, Perper JA, Moritz G, et al. Familial risk factors for adolescent suicide: a case-control study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1994;89:52–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb01485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Murphy GE, Wetzel RD. Family history of suicidal behavior among suicide attempters. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1982;170:86–90. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198202000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gould MS, Fisher P, Parides M, et al. Psychosocial risk factors of child and adolescent completed suicide. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:1155–1162. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830120095016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sahn EE, Garen PD, Silver RM, et al. Scleroderma following augmentation mammoplasty. Report of a case and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:1198–1202. doi: 10.1001/archderm.126.9.1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Spiera H. Scleroderma after silicone augmentation mammoplasty. JAMA. 1988;260:236–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schumann D. Health risks for women with breast implants. Nurse Pract. 1994;19:19–20. 3–5, 9–30. doi: 10.1097/00006205-199407000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Brozena SJ, Fenske NA, Cruse CW, et al. Human adjuvant disease following augmentation mammoplasty. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124:1383–1386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kumagai Y, Shiokawa Y, Medsger TA, Jr, et al. Clinical spectrum of connective tissue disease after cosmetic surgery. Observations on eighteen patients and a review of the Japanese literature. Arthritis Rheum. 1984;27:1–12. doi: 10.1002/art.1780270101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Oberle K, Allen M. Breast augmentation surgery: a women's health issue. J Adv Nurs. 1994;20:844–852. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1994.20050844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Maijers MC, de Blok CJ, Niessen FB, et al. Women with silicone breast implants and unexplained systemic symptoms: a descriptive cohort study. Neth J Med. 2013;71:534–540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Overholser JC, Braden A, Dieter L. Understanding suicide risk: identification of high-risk groups during high-risk times. J Clin Psychol. 2012;68:349–361. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bondurant S, Ernster V, et al. Implants; IoMUCotSoSB. Safety of silicone breast implants. Washington (DC): The National Academies Press; 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Immunology of silicone [Internet] Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 1999. [cited 2014 Jul 28]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44795/ [Google Scholar]

- 77.Stisi S, Cazzola M, Buskila D, et al. Etiopathogenetic mechanisms of fibromyalgia syndrome. Reumatismo. 2008;60(Suppl 1):25–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Russell IJ, Vaeroy H, Javors M, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid biogenic amine metabolites in fibromyalgia/fibrositis syndrome and rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35:550–556. doi: 10.1002/art.1780350509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Engstrom G, Alling C, Blennow K, et al. Reduced cerebrospinal HVA concentrations and HVA/5-HIAA ratios in suicide attempters. Monoamine metabolites in 120 suicide attempters and 47 controls. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 1999;9:399–405. doi: 10.1016/s0924-977x(99)00016-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nordstrom P, Samuelsson M, Asberg M, et al. CSF 5-HIAA predicts suicide risk after attempted suicide. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1994;24:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Roy A, De Jong J, Linnoila M. Cerebrospinal fluid monoamine metabolites and suicidal behavior in depressed patients. A 5-year follow-up study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46:609–612. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810070035005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Asberg M, Traskman L, Thoren P. 5-HIAA in the cerebrospinal fluid. A biochemical suicide predictor? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1976;33:1193–1197. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1976.01770100055005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lidberg L, Tuck JR, Asberg M, et al. Homicide, suicide and CSF 5-HIAA. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1985;71:230–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1985.tb01279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Arango V, Huang YY, Underwood MD, et al. Genetics of the serotonergic system in suicidal behavior. J Psychiatr Res. 2003;37:375–386. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(03)00048-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wilson KG, Kowal J, Henderson PR, et al. Chronic pain and the interpersonal theory of suicide. Rehabil Psychol. 2013;58:111–115. doi: 10.1037/a0031390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sher L. Cosmetic breast implants and suicide. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114:601–602. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000128496.36215.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Holmich LR, Lipworth L, McLaughlin JK, et al. Breast implant rupture and connective tissue disease: a review of the literature. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120:62S–69S. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000286664.50274.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Janowsky EC, Kupper LL, Hulka BS. Meta-analyses of the relation between silicone breast implants and the risk of connective-tissue diseases. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:781–790. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003163421105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hajdu SD, Agmon-Levin N, Shoenfeld Y. Silicone and autoimmunity. Eur J Clin Invest. 2011;41:203–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2010.02389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Caldeira M, Ferreira AC. Siliconosis: autoimmune/inflammatory syndrome induced by adjuvants (ASIA) Isr Med Assoc J. 2012;14:137–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.McBeth J, Silman AJ. The role of psychiatric disorders in fibromyalgia. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2001;3:157–164. doi: 10.1007/s11926-001-0011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bell IR, Baldwin CM, Schwartz GE. Illness from low levels of environmental chemicals: relevance to chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia. Am J Med. 1998;105:74S–82S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00162-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Richards S, Cleare AJ. Fibromyalgia: biological correlates. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2000;13:623–628. [Google Scholar]