Abstract

Background:

Trauma is the leading killer in the young age children, but data about the injury burden on pediatric population are lacking. The aim of this study is to describe the epidemiology and outcome of the traumatic injuries among children in Qatar.

Materials and Methods:

This is a retrospective analysis of a trauma registry database, which reviewed all cases of serious traumatic injury (ISS ≥ 9) to children aged 0–18 years who were admitted to the national pediatric Level I trauma center at the Hamad General Hospital (HGH), over a period of one year. Data included demographics, day of injuries, location, time, type and mechanism of injuries, co-morbidity, safety equipment use, pre-hospital intubation, mode of pre-hospital transport, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), Injury Severity Score (ISS), emergency department (ED) intervention, hospital length of stay and mortality outcome.

Results:

The incidence of severe pediatric trauma was 163 per 280,000 children who visited the ED of HGH in 2011. Out of them, 83% were male, mean age was 9.6 ± 5.9 years and mortality rate was 1.8%. On presentation to the ED, the mean ISS was 13.9 ± 6.6 and GCS was 13.4 ± 3.8. Over half of the patients needed ICU admission. For the ages 0-4 years, injuries most frequently occurred at home; for 5-9 years (59%) and 15-18 years (68%), the street; and for 10-14 years (50%), sports and recreational sites. The most common mechanisms of injury for the age groups were falls for 0-4 years, motor vehicle collision (MVC) or pedestrian injury for 5-9 years, all-terrain vehicle (ATV)/bicycle injuries for 10-14 years, and MVC injuries for 15-18 years. Head (34%) and long bone (18%) injuries were the most common, with 18% suffering from polytrauma. None of the patients were using safety equipment when injured.

Conclusion:

Traumatic injuries to children have an age- and mechanism-specific pattern in Qatar. This has important implications for the formulation of focused injury prevention programs for the children of Qatar.

Keywords: Children, home safety, Qatar, road traffic injuries, trauma

INTRODUCTION

Pediatric traumatic injury (PTI) is a significant public health problem worldwide.[1] In Qatar, injuries are the leading identified cause of death and disease burden for all ages, specifically road traffic injuries (RTIs).[2,3] Using a 15-year national death certificate registry, RTIs were identified as a leading cause of mortality for children aged 0-18 years in Qatar from 1993-2007.[4]

Qatar is a rapidly growing country in the Middle East with approximately 2.1 million people – of which only 15% are Qatari citizens and the rest are made up of expatriate workers and their families.[5] For the general population, there are 3 males for every female and 81% are from 20 to 59 years of age. Children of age ≤18 years have very different demographics when compared to the general population. They comprise 16.7% of the total population with 59% male and 38.4% Qatari.[6]

Previous works in the field of trauma and injury research in Qatar have already described the epidemiology and outcomes of occupational[7,8] pedestrian,[9,10] traumatic brain[11,12] and RTIs.[2] There is a great need to present and analyze more recent data on PTIs because this population needs specific evidence for the formulation of targeted and appropriate injury prevention programs.

Herein, we aim to describe and analyze the epidemiology and outcomes of serious PTIs in Qatar that can be used as a source of public awareness toward injury prevention.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is a retrospective analysis of a trauma registry database, which reviewed all cases of traumatic injury to children aged 0–18 years who were admitted to the national pediatric Level I trauma center at the Hamad General Hospital (HGH), over a period of one year (January 2011 to December 2011). HGH is the national trauma referral hospital, the only one that receives and treats all cases of serious PTI in Qatar, with a dedicated trauma team that is the main hub of a national trauma system that is multi-disciplinary and inclusive of pre-hospital to rehabilitation services. Patients from the Trauma Registry who met the inclusion criteria had their charts reviewed. Data included demographics, month, day, time and location of injury, type and mechanism of injury, co-morbidity, use or non-use of safety equipment, mode of transport, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), Injury Severity Score (ISS), emergency department (ED) intervention/s (endotracheal intubation and surgical procedures), blood transfusion, hospital length of stay (LOS), patient disposition, outcome and prognosis. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from Research Ethics Committee, at Medical Research Center, Hamad Medical Corporation (HMC), Doha, Qatar.

Data were presented as proportions, mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median as appropriate. The χ2 test was used to compare proportions between the groups. Pearson correlation (r) was used to assess the correlation between different quantitative variables. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). Data analysis was carried out using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 18 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

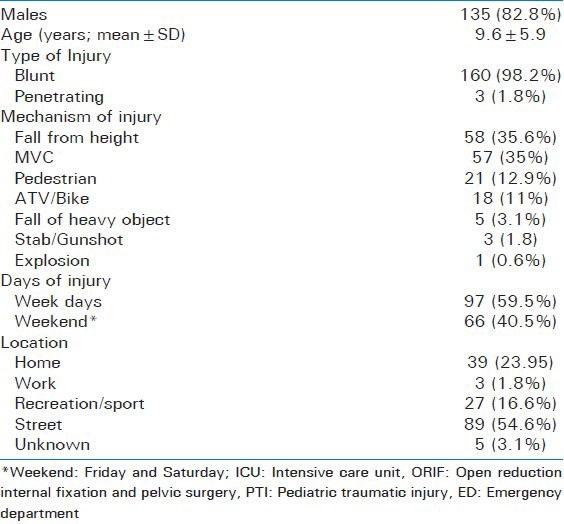

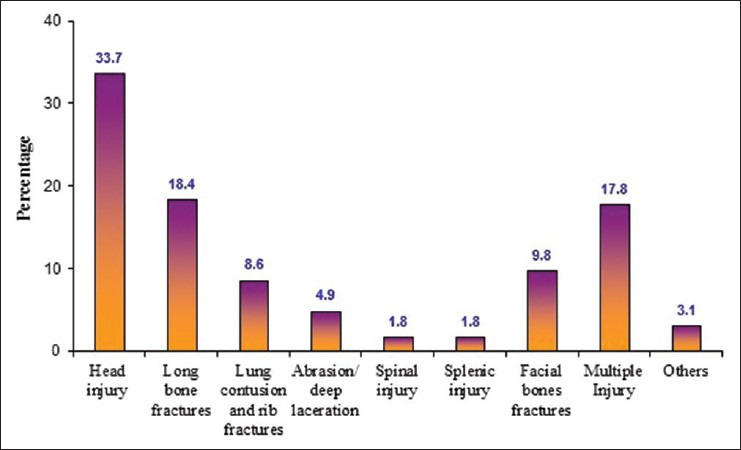

The incidence of PTIs was 163/280,000 children seen in ED during the year 2011. A total of 163 children (135 males and 28 females), comprising 10.3% of all trauma admissions, were included in the study and their mean age was 9.6 ± 5.9 years (range from 4 months to 18 years). Table 1 shows the demographics and characteristics of the entire study population. Most were male (82.8%), victims of blunt, unintentional injury (98.2%) that most commonly occurred on the street (54.6%). The leading mechanisms were falls (35.6%), motor vehicle collisions (MVCs; 35%), pedestrian accidents (12.9%) and all-terrain vehicle (ATV)/bike accidents (11%). Table 2 shows the mode of transport, disposition and outcome of PTIs. The majority of patients were transported by ground ambulance (64.4%) and admitted to the general surgical units (56%). Almost half of the patients (44%) needed admission to the trauma (24%) or pediatric ICU (20%), less than one-third (32.5%) needed a surgical procedure; one in 10 needed a blood transfusion (10.4%) and endotracheal intubation (9.2%). The mean GCS at the scene was 13.2 ± 3.5 (available for only 85 cases). The mean GCS on presentation to the ED was 13.4 ± 3.8 (range, 3–15) and the mean initial ISS was 13.9 ± 6.6 (range, 9–38). The LOS was positively correlated respectively with ISS (r = 0.24, P < 0.002), age (r = 0.278, P < 0.001), GCS at the scene (r = −0.305, P < 0.005) and GCS at the ED (r = −0.305, P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Demographics and characteristics of PTI cases

Table 2.

Mode of transport, disposition and clinical outcome of PTI cases

There was a correlation between ISS and age in years (r = 0.22, P < 0.005) and GCS at the ED (r = –0.53, P < 0.001). There was a negative correlation between GCS at ED and age of the patient (r= –0.21, P < 0.008). No significant associations were found between ISS with gender, mechanism of injury and trauma type.

Three children died for a mortality rate of 1.8% and one was discharged with a permanent disability (quadriplegia). None of the patients was using safety equipment (i.e. child car restraint system, seat belt or bicycle helmet) at the time of injury.

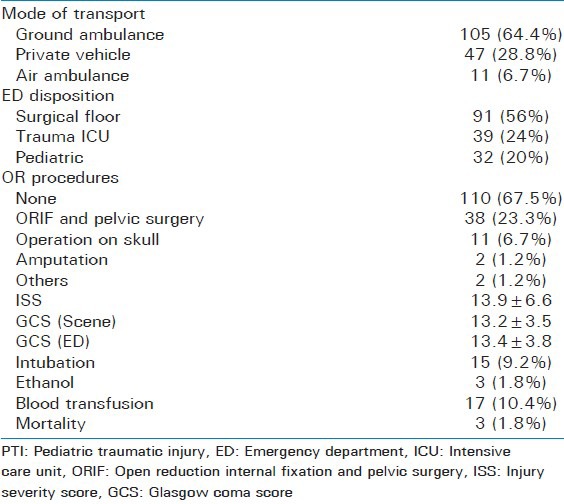

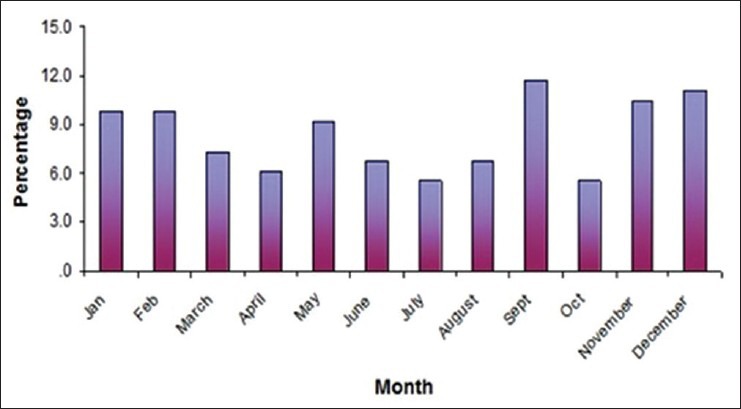

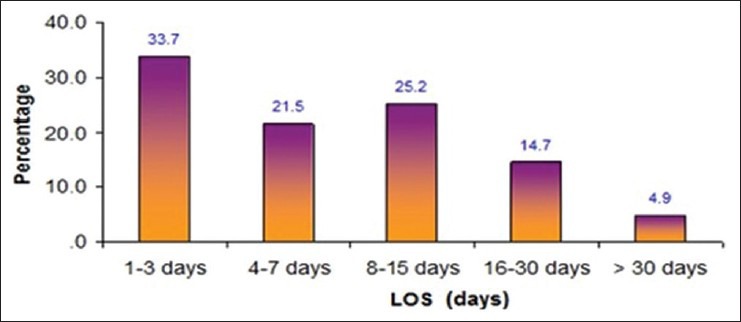

A disproportionate percentage of injuries of injuries (40%) [observed/expected = 0.4/0.286 = 1.40 times higher] in children occurred during the weekends. There was a trend toward more patients being admitted during the cooler months of the year [November to March], but this was statistically insignificant and most patients were admitted in September [Figure 1]. Head injury (33.7%) and long bone fractures (18.4%) were the most common types of trauma, followed by multiple injuries (17.8%) and facial fractures (9.8%) [Figure 2]. The median hospital LOS was 6 days with a range from 1–60 days. Majority of the patients (55.2%) stayed for one week in the hospital followed by a two-week (25.2%) stay in the hospital; only 5% cases required a longer hospital stay (>30 days) [Figure 3].

Figure 1.

Proportion of trauma admissions by month of the year, ages 0-18 years, ISS >8, Hamad General Hospital, 2011

Figure 2.

Types of injury in trauma patients, ages 0-18 years, ISS >8, Hamad General Hospital, 2011

Figure 3.

Length of stay (LOS) in the hospital (days)

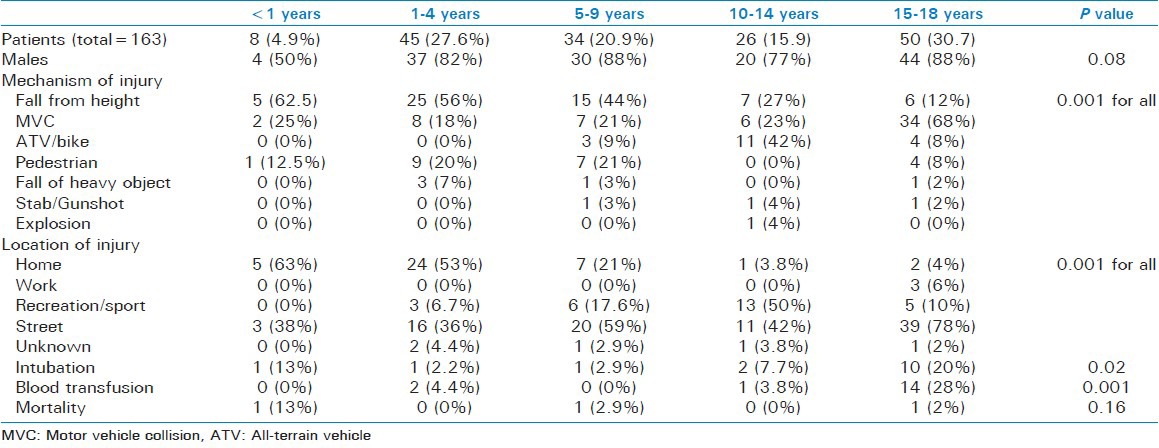

Table 3 summarizes the demographics, mechanism/location of injury and outcome by different age groups. Teenagers (30.7%), 15-18 years, and toddlers (27.6%), 1-4 years, made up the majority of the admissions for PTI. Fall from height contributed a significantly higher proportion of the injuries among infants (<1 yr; 62%) and young children (1-4 yrs; 56%) than other age groups (P = 0.0001). MVC-related injuries were the most common injury for teenagers (68%) from 15-18 years. ATV- and bicycle-related injuries were the most common injury for adolescents (10-14 yrs; 42%). Pedestrian injuries were most frequently seen among young children of age group 1-5 years (20%) and 5-10 years (21%). The need for intubation (20%) and blood transfusion (28%) was more frequent for teenagers as compared to other age groups (P = 0.0001). For the ages 0-4, injuries most frequently occurred at home; for 5-9 years (59%) and 15-18 years (68%), the street was the most common site; and for 10-14 years (50%), sports and recreational sites were the most common locations. These locations correlate with the most common mechanism of injury for each of the age groups: Falls for 0-4 years, MVC or pedestrian injury for 5-9 years, ATV/bicycle injuries for 10-14 years and MVC injuries for 15-18 years.

Table 3.

Demographics, mechanism/location of injury and outcome by different age groups

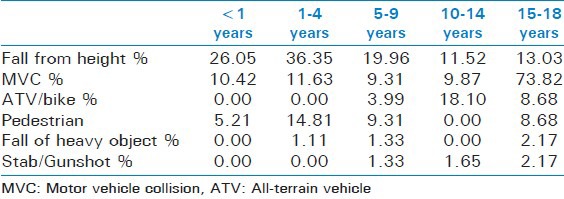

Table 4 shows the incidence of the various mechanisms of serious PTI in Qatar, classified according to age group. The age-related nature of serious PTI is clearly demonstrated with the highest incidence for pedestrian and falls-related injuries for 1-4 year olds, for MVC injuries for 15-18 year olds and ATV/Bike injuries for 10-14 year olds. Table 5 summarizes the incidence of pediatric trauma based on the number of population in each age group.

Table 4.

Incidence (per 100,000) of serious pediatric injuries, by mechanism of injury and age group, Hamad Trauma center, Doha, Qatar, 2011

Table 5.

incidence of injury based on the population in 2011

DISCUSSION

This report describes the most recent epidemiology and outcome of PTIs in Qatar by age group, location and mechanism of injury. Most injuries and injury deaths happened in the youngest and oldest age groups. Infants, up to the age of 1, are most commonly injured because of fall at home. Toddlers, from 1 to 4 years, are most commonly injured also at home because of fall or by a falling object. Older children, from 5-9 years, were most commonly injured in the street as a pedestrian. Adolescents were most commonly injured during recreation or sports while using an ATV or bicycle. Teenagers suffered the most from MVCs.

This report on PTIs in Qatar is from a nationally representative dataset of moderate to severely injured pediatric trauma patients [ISS ≥ 9 and ages 0-18 years] admitted to the national Level I trauma referral hospital. This report provides data that have not been provided by previous reports that focused on injury deaths alone by describing the characteristics and outcomes of child victims of serious injury, majority of whom survived to be discharged from the hospital. Its results will serve as the evidence base for policies governing the provision of care, the training and recruitment of staff, and future directions for research on and development of services for pediatric trauma patients in Qatar.

There are certain limitations of the present study with the retrospective nature of the data collection as one of the major limitations. Data obtained from a trauma registry often lack information surrounding the pre-event characteristics of both the agent and the victim of injury.[13] Likewise, data on the in-hospital morbidities or complications and the long-term disability of the patients were not fully captured by this retrospective data review. Lastly, our trauma center does not treat victims of near-drowning or burn injuries; as such these injuries are not described in this paper.

The bimodal age distribution,[9] the most frequently injured ages[10] and male over-representation[1] of our study population were very similar to those reported in the US and globally. Locally, we have reported similar findings for gender, mortality rates, and leading mechanism of injury for infants and toddlers and for pediatric victims of road traffic and home injuries. In a less severely injured infant and toddler population (ages 0-4, median ISS = 4), home was the location of 66% of injuries, 70% of victims were male, a fall was the most frequent mechanism with a mortality rate of 2.1%.[14] In that same population, we noted the same non-use of child restraint systems (0%)[14] and a 1.2% restraint use rate among a population from 0-18 years of age.[15] These usage rates are significantly lower than those reported for adult trauma patients by Munk et al. in 2008 (33%) and front seat passengers by the Ministry of Interior in 2010 (50%).[16,17]

There was a disproportionate percentage of PTIs that occurred during the weekends. However, an earlier report of traumatic brain injury among children observed no difference in injury rates with respect to weekday.[18]

In our study, PTI cases mainly presented with head injury, long bone fractures and multiple injuries. Our study findings corroborate with earlier reports of childhood injuries, which showed head and extremities to be the most commonly injured body regions.[19,20]

More than half of the cases were discharged from the hospital after one week of stay. Moreover, a positive correlation was observed among the hospital LOS with age and ISS in our study. Our findings correlate with an earlier study, which demonstrated that patients with ISS score ≥ 9 need longer hospital stay (>2 days) as compared to the cases with ISS < 9, which suggest that patients with higher ISS needs longer hospital stay.[19] Therefore, ISS correlates linearly with morbidity, mortality and LOS in the hospital.[21]

The present study also analyzes the different mechanisms of injury according to various age groups. The age specificity of both mechanisms and location of injury are similar to our previous report on a less severely injured population (ages 0-18 years, median ISS = 4), which showed that the age groups differed significantly by mechanism and location of injury. Falls were the predominant cause of injury from 0-9 years of age. RTIs were the leading cause of injury from 10-18 years. Pedestrian injuries were the most common from 5-9 years. Other road-related injuries from bicycle or ATV crashes were most common from 5-14 and 10-14 years, respectively. The home was the location for more than 50% of all injuries to children ages 0-5 and the street for those ages 10-18.[19]

Teenagers (15-18 yrs) sustained the most MVC-related injuries in our series. This is consistent with our report of the increasing trend of MVC-related hospitalization with increasing age, and these injuries were highest among adolescents (≥15 years)[15,19,22,23,24] and that the major cause of mortality among adolescents and young adults are from RTIs.[2]

Killingsworth et al.[25] analyzed 5,292 ATV injuries among children; they found that children in the age group 10-14 years were mainly involved in ATV-related injuries and experienced hospital admission. Similarly, most of the ATV/bike-related injuries were seen among adolescents (10-14 yrs). Alani et al. reported that 20% of ATV victims in Qatar were younger than 14 years of age.[26]

With respect to pedestrian injuries, young children (5-9 yrs) sustained most of these injuries in our study. Alani et al., also[26] demonstrated that the hospitalization rates for pedestrian injury were highest in patients of 5-9 years of age. We have also reported that pedestrian injuries also affect children as one in 7 pedestrian injuries in Qatar affect a child younger than 14 years.[9]

The overall mortality rate from this population was computed as 1.8% (3 cases). Similar mortality rates have been reported by earlier studies investigating pediatric trauma.[14,21,22,27,28]

Under most circumstances, a mortality rate of 1.8% for patients with serious injuries [ISS ≥ 9] would be acceptable. However, when we correlated the number of injury deaths from this trauma registry dataset with the national database of injury deaths, we found that only 10.3% of children who died from injury in 2011 were admitted to the national Level I trauma center. This merits further evaluation of pre-hospital ambulance services for PTIs and highlights the need for the national implementation of primary injury prevention efforts that will include passenger, ATV, bicycle and home safety programs that will decrease the mortality and disability of the 90% of victims who do not survive their injuries long enough to arrive at the hospital for medical attention. The implementation of proven interventions that are age-appropriate[29] and readily applicable to this diverse cultural milieu will be ideal.

Ten percent of all trauma admissions to the Hamad Trauma Center were pediatric patients, from 0 to 18 years of age. Almost half of these patients needed admission to an ICU and 9% needed endotracheal intubation. This amounts to 80 children admitted to an ICU and 16 needing the application of urgent advanced pediatric airway skills every year. With the growing population, these data should influence staff training, capacity development, medical education and strategic planning for the provision of pediatric trauma services in the future.

In conclusion, motor vehicle crashes are the major cause of pediatric injury in Qatar. Head and long bone injuries were the most common injuries in children. GCS on the scene is an important predictor of the length of hospitalization. A lot must be done regarding safety education of parents and caregivers as none of the patients were using a safety measure, i.e. seat belt, car seat belt or helmet, when injured. The present study highlights the importance and urgent need for improving public awareness toward pediatric safety measures (at home, school and on the road), implementing primary injury prevention strategies and improving pediatric pre-hospital services to reduce the morbidity and mortality of injured children in Qatar.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank all members and staff of the Trauma Team, Hamad General Hospital, Doha, Qatar, for their supports.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Margie Peden, et al., editors. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. World report on child injury prevention. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Consunji RJ, Peralta RR, Al-Thani H, Latifi R. The implications of the relative risk for road mortality on road safety programmes in Qatar. Inj Prev. 2014 doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2013-040939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bener A, Zirie MA, Kim EJ, Al Buz R, Zaza M, Al-Nufal M, et al. Measuring burden of diseases in a rapidly developing economy: State of Qatar. Glob J Health Sci. 2013;5:134–44. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v5n2p134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bener A, Hussain SJ, Ghaffar A, Abou-Taleb H, El-Sayed HF. Trends in childhood trauma mortality in the fast economically developing State of Qatar. World J Pediatr. 2011;7:41–4. doi: 10.1007/s12519-010-0208-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qatar by Numbers. [Last accessed on 2014 Feb 2]. Available from: www.qatarliving.com/node/4777796 .

- 6.Vital Statistics Annual Bulletin (Births and Deaths) (2010 and 2011) Qatar Statistics Authority. 2010. [Last accessed on 2014 Feb 15]. Available from: http://www.qsa.gov.qa/eng/index.htm .

- 7.Tuma MA, Acerra JR, El-Menyar A, Al-Thani H, Al-Hassani A, Recicar JF, et al. Epidemiology of workplace-related fall from height and cost of trauma care in Qatar. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci. 2013;3:3–7. doi: 10.4103/2229-5151.109408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al Thani H, El-Menyar A, Abdelrahman H, Zarour A, Consunji R, Peralta R, et al. Workplace-related traumatic injuries: Insights from a rapidly developing middle eastern country. J Environ Public Health 2014. 2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/430832. 430832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Latifi R, El-Menyar A, Al-Thani H, Zarour A, Parchani A, Abdulrahman H, et al. Traffic-related pedestrian injuries amongst expatriate workers in Qatar: A need for cross-cultural injury prevention programme. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot. 2014 doi: 10.1080/17457300.2013.857693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abdulrazzaq H, Zarour A, El-Menyar A, Majid M, Al Thani H, Asim M, et al. Pedestrians: The daily underestimated victims on the road. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot. 2013;20:374–9. doi: 10.1080/17457300.2012.748811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.El-Matbouly M, El-Menyar A, Al-Thani H, Tuma M, El-Hennawy H, AbdulRahman H, et al. Traumatic brain injury in Qatar: Age matters--insights from a 4-year observational study. ScientificWorldJournal 2013. 2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/354920. 354920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parchani A, El-Menyar A, Al-Thani H, Tuma M, Zarour A, Abdulrahman H, et al. Recreational-related head injuries in Qatar. Brain Inj. 2013;27:1450–3. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2013.823664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sethi D, et al., editors. World Health Organization; 2004. Guidelines for conducting community surveys on injuries and violence. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Consunji RJ, Peralta R, Al-Thani H, Latifi R. Doha, Qatar: 2nd Annual Child Health Research Day. Sick Kids International/Hamad Medical Corporation Partnership. 28 January; 2012. The injury epidemiology of infants and toddlers in Qatar. Poster Presentation. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Consunji R, Peralta R, El Menyar A, Al-Thani H, Mollazaeh MR, Hepp H, et al. Doha, Qatar: 4th Annual Child Health Research Day. Sick Kids International/Hamad Medical Corporation Partnership, 4 February; 2012. Pediatric road traffic injuries in Qatar: Trends and statistics from the HMC Trauma Registry [2010-2012] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Munk MD, Carboneau DM, Hardan M, Ali FM. Seatbelt use in Qatar in association with severe injuries and death in the prehospital setting. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2008;23:547–52. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x00006397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. World Health Organization Global status report on road safety 2013: Supporting a decade of action: Summary. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koepsell TD, Rivara FP, Vavilala MS, Wang J, Temkin N, Jaffe KM, et al. Incidence and descriptive epidemiologic features of traumatic brain injury in King County, Washington. Pediatrics. 2011;128:946–54. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Consunji R, Peralta R, Al Thani H, Hepp H, Mollazehi M, Latifi R. Lyon, France: European Society for Emergency and Trauma Surgery Meeting, May; 2013. Pediatric trauma in Qatar: One size does not fit all for injury prevention. Free Paper Presentation. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guice KS, Cassidy LD, Oldham KT. Traumatic injury and children: A national assessment. J Trauma. 2007;63(6 Suppl):S68–80. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31815acbb6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Odetola FO, Mann NC, Hansen KW, Patrick S, Bratton SL. Source of admission and outcomes for critically injured children in the mountain states. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164:277–82. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gardner R, Smith GA, Chany AM, Fernandez SA, McKenzie LB. Factors associated with hospital length of stay and hospital charges of motor vehicle crash related hospitalizations among children in the United States. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:889–95. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.9.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams AF. Teenage passengers in motor vehicle crashes: A summary of current research. [Last accessed on 2013 Dec 15]. Available from: http://www.iihs.org/research/topics/pdf/teen_passengers.pdf . Published December 2001.

- 24.Traffic Safety Facts 2004. Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration National Center for Statistics and Analysis; 2004. [Last accessed on 2013 Dec 16]. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Report DOT HS 809 919. http://www-nrd.nhtsa.dot.gov/Pubs/TSF2004.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 25.Killingsworth JB, Tilford JM, Parker JG, Graham JJ, Dick RM, Aitken ME. National hospitalization impact of pediatric all-terrain vehicle injuries. Pediatrics. 2005;115:e316–21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alani M, Zarour A, Almadani A, Al-Aieb A, Hamzawi H, Maull KI. All terrain vehicle (ATV) crashes in an unregulated environment: A prospective study of 56 cases. [Last accessed on 2014 Mar 01];J Emerg Med Trauma Acute Care. 2012 1 Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.5339/jemtac.2012.1 . [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cyr C, Xhignesse M, Lacroix J. Severe injury mechanisms in two paediatric trauma centres: Determination of prevention priorities. Paediatr Child Health. 2008;13:165–70. doi: 10.1093/pch/13.3.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brison RJ, Wicklund K, Mueller BA. Fatal pedestrian injuries to young children: A different pattern of injury. Am J Public Health. 1988;78:793–5. doi: 10.2105/ajph.78.7.793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Winn DG, Agran PF, Castillo DN. Pedestrian injuries to children younger than 5 years of age. Pediatrics. 1991;88:776–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]