Abstract

Introduction:

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) requires rapid diagnosis for the initiation of antibiotics. Its diagnosis is usually based on manual examination of ascitic fluid (AF) having long reporting time. AF infection is diagnosed when the fluid polymorphonuclear leukocyte (PMNL) concentration ≥250 cells/mm3.

Aims and Objectives:

Aim was to evaluate the diagnostic utility of leukocyte esterase (LE) reagent strip for rapid diagnosis of SBP in patients who underwent abdominal paracentesis and to calculate the sensitivity, specificity, positive, and negative predictive values.

Materials and Methods:

The study was carried out on 103 patients with ascites. Cell count of AF as determined by colorimetric scale of Multistix 10 SG reagent strip was compared with counting chamber method (PMNL count ≥250 cells/mm3 was considered positive).

Results and Observations:

Of the 103 patients SBP was diagnosed in 20 patients, 83 patients were negative for SBP by manual cell count. The sensitivity and specificity of the LE test for detecting neutrocytic SBP taking grade 2 as cut off were 95% and 96.4% respectively, with a positive predictive value of 86.4% and a negative predictive value of 98.8%. Diagnostic accuracy of LE test was 96.1%.

Discussion:

There was a good correlation between the reagent strip result and PMNL count. The LE strip test is based on the esterase activity of activated granulocytes which reacts with an ester-releasing hydroxyphenylpyrrole causing a colour change in the azo dye of reagent strip. It is a very sensitive and specific method for the prompt detection of elevated PMNL count, and represents a convenient, inexpensive, simple, and bedside method for diagnosis of SBP. A negative LE test result excludes SBP with a high degree of certainty.

Keywords: Bacterial, diagnosis, esterases, leukocytes, leukocytes esterases, peritonitis, reagent strips.

INTRODUCTION

Ascites remains the commonest of the three major complications of advanced or decompensated cirrhosis (along with hepatic encephalopathy and variceal hemorrhage). Cirrhotics with ascites have 10% probability of developing the first episode of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) over a period of one year.[1] SBP is defined as the infection of ascitic fluid (AF) in the absence of a contiguous source of infection and/or an intra-abdominal (and potentially surgically treated) inflammatory focus. A total of 50% of SBP episodes are present at the time of hospital admission, while the remainder are acquired during the hospitalization period.[2]

The prevalence of SBP in patients of cirrhosis with ascites range between 10% and 30%, depending on whether antibiotic prophylaxis is used or not.[3] The mortality of untreated SBP remains high (>80%), and patient course and clinical outcome is based on an aggressive approach aiming to rapid diagnosis and prompt initiation of antibiotic therapy.[4] Although prompt initiation of antibiotics produces satisfactory response in most cases, the mortality still remains very high at 30%-50%.[5,6,7]

Diagnosis of SBP

Abdominal pain and fever are the most characteristic symptoms of SBP, followed by vomiting, ileus, diarrhea, hepatic encephalopathy, gastrointestinal bleeding, and renal impairment.[3,8,9] These clinical manifestations of SBP can be subtle and insidious, and its diagnosis requires a high index of clinical suspicion. Moreover, many patients with SBP may be totally asymptomatic.[3] Therefore, a clinical diagnosis of infected AF without a paracentesis is not adequate.[1] Abdominal paracentesis is considered necessary for all patients with ascites on hospital admission, in-patient cirrhotics with ascites who develop the following:

Local symptoms or signs of peritoneal infection

Clinical systemic signs of sepsis,

Hepatic encephalopathy, (sudden or unexplained), renal impairment, and/or who develop gastrointestinal bleeding.[3]

Although the combination of an elevated polymorphonuclear neutrophilic leukocyte (PMNL) count and the yield of cultures of the AF are considered the gold standard for the diagnosis of SBP,[3,10,11] an AF PMNL count ≥250/mm3, irrespective of the AF culture result, is universally accepted nowadays as the best surrogate marker for diagnosing SBP.[12] The presence of positive AF cultures is confirmatory, but by no means a necessary prerequisite for instigation of antibiotic therapy.[4] The shortcomings are- first, the results of AF culture not readily available, postponing the diagnosis and treatment of the infection. Second, one of the most frequent variants of AF infection is culture-negative neutrocytic ascites despite the use of sensitive methods, which occurs in approximately 30%-50% of patients.[3,10,11]

Furthermore, facilities to do a quick total and differential leukocyte count may not be easily available, especially in some small patient care units especially in the rural settings and after routine hours. Manual AF PMNL cell count sometimes cannot be done on emergency basis and is prone to human errors. It is also laborious. The use of automated cell counters requires an expensive machine in addition to round the clock availability of lab facility.[13]

Thus, there is need for a quick, simple, and rapid bedside diagnostic test for SBP. Leukocyte esterase reagent (LER) strips, developed initially to test for PMNL in urine,[14] have shown to be sensitive and accurate predictor of presence of PMNL other body fluids such as pleural fluid,[15,16] cerebrospinal fluid, seminal, peritoneal fluid,[17] and otitis media effusions.[18]

Despite the fact that these reagent strips are not specific for PMNLs, their diagnostic performance is promising.[13] When used on AF, leukocyte esterase (LE) test can act as a marker of AF infection.[15] In studies in developed countries, this test reduced the time for diagnosis of SBP from a few hours to a few minutes.[19]

In developing countries like India with a large rural population, the need for a sensitive and rapid bedside diagnostic test for SBP is even higher.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

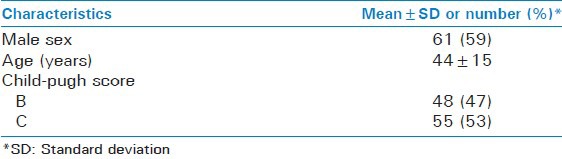

A total of 103 patients admitted in ward of Pt. B. D. Sharma PGIMS, Rohtak with clinical diagnosis of cirrhotic ascites, were included in the study. The diagnosis of cirrhosis with ascites was based on clinical, biochemical, and ultrasonographic findings.[20] Peripheral blood samples were obtained for white blood cell (WBC), PMNL counts, biochemical markers (glucose, albumin, creatinine, lactic dehydrogenase, and bilirubin) and coagulation parameters evaluation. The mean age of patients were 44 ± 15 years, there was a predominance of males (61 patients, 59%). Alcohol was the most common cause of liver cirrhosis. A total of 47% of patients were classified as Child B and 53 as Child C (51%). The demographic characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 103 cirrhotic patients who underwent the paracentesis

Patients with previous history of a surgical procedure in the previous 4 weeks were excluded from the study, as well as those with other causes of PMNL increase in the AF such as tuberculosis, pancreatitis, and peritoneal carcinomatosis.

First, the patients underwent paracentesis as dictated by standard medical practice and immediately after the procedure, some amount of AF was sent to the laboratory in tubes containing heparin for determination of total and differential WBC counts. Another tube without anticoagulant was used for determination of protein, albumin, glucose, and lactic dehydrogenase. Patients in whom:

AF was grossly bloody

<30 mL of AF was obtained during paracentesis, and

AF samples that have clotted during processing were also excluded from the study.

The cultures were seeded at bedside with the inoculation of 10 mL of AF into aerobic and anaerobic media blood culture bottles.

The reagent strip (Multistix 10SG) was immersed immediately in 5mL of AF placed on a dry and clean container as described by the manufacturer for identification of leukocyte esterase. After 2 min, the reagent strip was read comparing the colour of the leukocyte reagent strip area with the colorimetric 5-grade scale depicted on the bottle. Based on the degree of colour change in the reagent strip area, the results were scored as grade 0 or nil, grade 1 or traces, grade 2 or low, grade 3 or moderate, and grade 4 or high. Reading of nil and trace was considered negative and not clinically significant; while reading of low, moderate, and high were considered as positive and clinically significant. This is supported by the manufacturer's guidelines (package insert) and the recommendations of Marquette et al.,[21] for urine testing.

SBP was diagnosed when the PMNL count was greater than 250 PMNL/mm3, in the absence of another intra abdominal source of infection. Culture positive neutrocytic cases were identified. Culture negative neutrocytic ascites was present when PMNL was greater than 250 PMNL/mm3 but the culture was negative. In patients with hemorrhagic ascites [i.e. ascites red blood cell (RBC) count >10,000/mm3], a subtraction of one PMNL per 250 RBCs was made. Secondary peritonitis was suspected when there was an abdominal source of infection, acute pancreatitis, or more than one organism in the AF culture.

Statistical analysis

Results of dipstick test were compared with PMNL cell count, AF culture and clinical data in all patients. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), accuracy and likelihood ratio of dipstick at different positive cut-off points (≥2, ≥3, and ≥ 4) in the diagnosis of SBP were calculated. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was elaborated to determine the best positive cut-off point for the reagent strip.

RESULTS

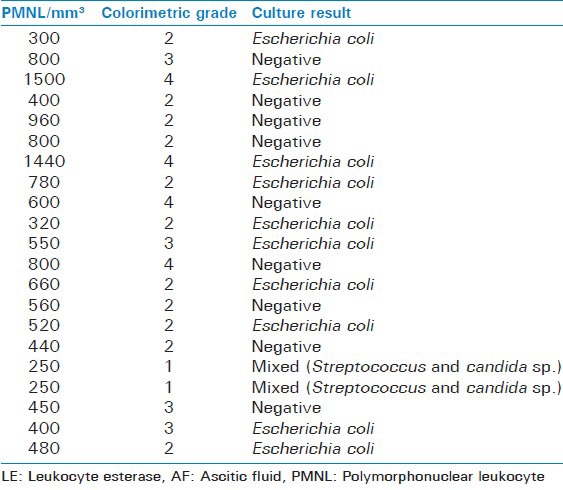

Of total 103 patients studied, 20 were found to have neutrocytic ascites on the basis of AF PMNL count. AF culture was positive in 11 of these cases (55%), with Escherichia coli in 10 cases, Streptococcus and Candida (mixed) species in one [Table 2].

Table 2.

LE test scores and AF culture results of ascitic fluids with PMNL count ≥250 cells/mm3

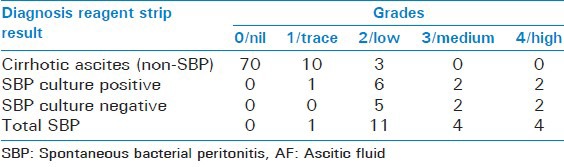

Rest of the 83 patients, did not have neutrocytic ascites. LE reagent strip test results were positive in 22 patients taking grade 2 as cut off with 14 having scores of low, 4 of moderate and 4 as high, 8 were positive taking grade 3 as cut off and 4 when taking grade 4 as cut off. Table 3 shows final diagnosis of AF samples and Multistix 10 SG Reagent Strips test result.

Table 3.

Final diagnosis of AF samples and Multistix 10 SG reagent strips test result

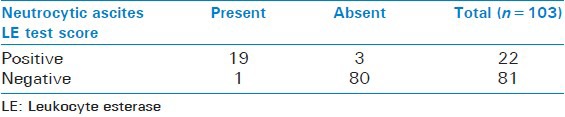

Of the 20 PMNL count positives specimens, LE test was positive in 19 taking grade 2 as cut off. The one left had PMNL count of 250 cells/mm3 showed trace in LE score, so considered false negative. The rest 3 (22-19) LE positive score thus were false positive. The remainder 81 patients of 103 were found to be negative on LE test, had scores of nil and trace.

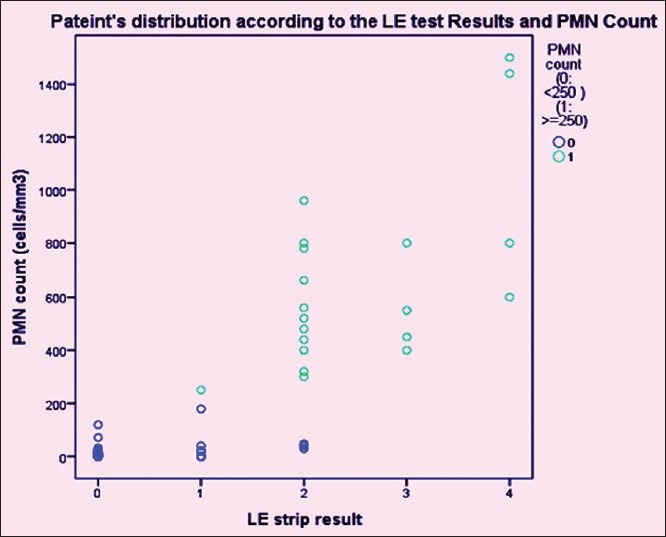

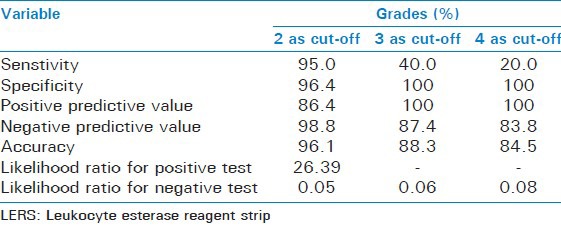

The final results of LE test in all 103 patients with grade 2 as cut off were evaluated as shown in Table 4 and patient's distribution according to the LE test results and PMNL count are shown in Figure 1. Table 5 shows the performance characteristics of LERS, using three different cut-offs in the diagnosis of SBP.

Table 4.

Evaluation of results of LE test in all patients with Grade 2 as cut-off

Figure 1.

Patients distribution according to the LE test results and PMNL Count

Table 5.

Performance characteristics of LERS, using three different cut-offs in the diagnosis of SBP

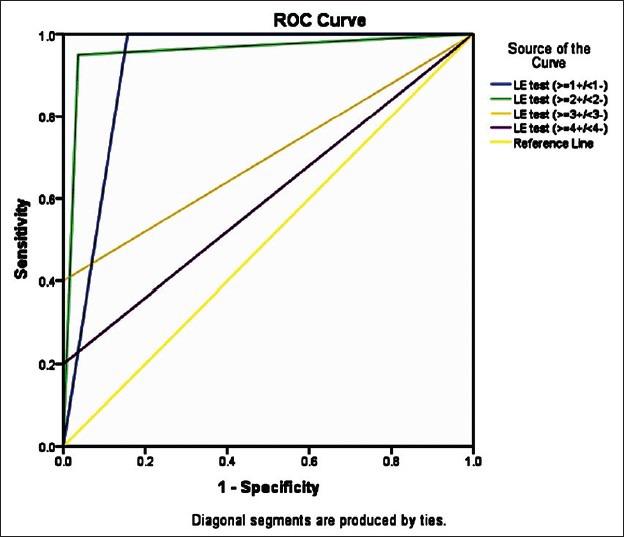

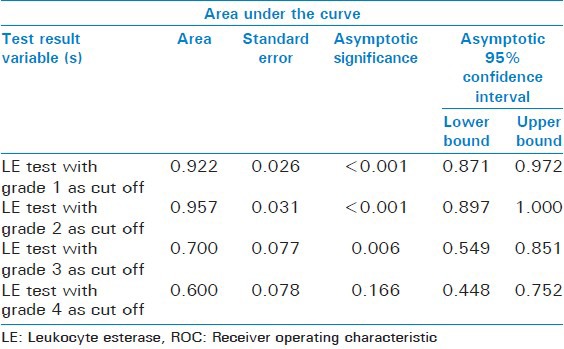

Considering the very high mortality of SBP the best cut-off point should be chosen based on the highest sensitivity achieved and the lowest false negative rate observed. This was reached with a cut-off point of grade 2 (though the specificity was slight less as compared with cut off of 3 and 4) and was later confirmed by the results of the ROC curve. However, in the clinical context of SBP, it may be better to use the cut-off with a highest sensitivity, even at the cost of some false positives, that is, grade 2. Figure 2 shows the ROC curve of the LE test taking 1, 2, 3, and 4 as cut offs and Table 6 shows its area under the curve. The ROC curve with cut off as 2 has the maximum area under curve of 0.957, which suggests cut off of 2 is the best.

Figure 2.

ROC curve of the LE test taking 1, 2, 3 and 4 as cut offs

Table 6.

Area under the ROC curve of the LE test taking 1, 2, 3, and 4 as cut offs

The mean time taken for cell count results from our laboratory was 2.7 h (range: 105–180 min), whereasthat for LER test was 2 min. The cost of each test was Indian Rupees (INR) 15 for the LER strip test and INR 300 for cell count.

DISCUSSION

The test is based on the esterase activity released from granulocytes present in the AF that reacts with an esterified chemical compound (derivatized pyrrole amino acid ester) in the reagent strip. Hydrolysis of this ester by esterase release 3-Hydroxy-5-phenyl-pyrrol which in turn reacts with a diazonium salt (present in the reagent strip) to yield a violet azo dye, the intensity of which correlates to leukocyte count.[22]

The study reveals that at the threshold of 250 PMNL/mm3 in AF, LE test is highly sensitive (95%) and specific (96.4%) for the diagnosis of AF infection (grade 2 as cut off).

Sometimes, there is formation of the leukocyte clump in AF which precludes the laboratory analysis.[23] In our study, repeat AF samples were required on six occasions, but we do not have data regarding the reason. An additional advantage to the chemical LE test is that it detects the presence of leukocytes that have been lysed and would not appear in the microscopic examination, accounting for its high sensitivity.[24]

There are many factors that influence the accuracy of the dipsticks. False-positive result can result from alteration of pH, osmolality, and temperature of the specimens. In urine, it has been demonstrated that the rate of leukocyte lysis decreases with decreasing pH and temperature, increasing osmolarity.[25] In addition, non-leukocyte cells can release esterase such as from pancreas and produce a false positive result.[26] PMNL can release leukocyte esterase into the extracelullar milieu. Crenation of leukocytes prevents release of esterases. Moreover, antibiotics can produce both false positive and negative results,[27] as the presence of the antibiotics decreases the sensitivity of the reaction. Finally, requirement of proper lighting to read the reagent strip colour scale, variability in colour perception, and variability of manual cytology are potential sources of inherent human error.

The false-positive rate is 4%. This information suggests that a precise colorimetric scale for 250 PMNL/mm3 is essential for an ideal dipstick to detect SBP.

The false negative result was found in one patient (5%), and it was confirmed that the patient with false-negative result did not receive antibiotics prior to abdominal paracentesis.

False-negative results may also occur in the presence of high concentrations of protein (greater than 500 mg/dL), glucose (greater than 3 g/dL), oxalic acid, and ascorbic acid. In this reaction, ascorbic acid also combines with the diazonium salt.[28]

Interestingly, the false-negative specimen had the manual PMNL cell count of 250/mm3, suggesting that the borderline number of PMNL cells in the specimen may lead to a false negative result. Although culture of this sample yielded two organisms (streptococcus species and candida species), the results of the reagent strips could perhaps be explained by lack of esterase activation in that AF sample.

A more detailed analysis of AF properties (pH, osmolarity, and protein content) may help determine source of false readings.

Overall in all 103 AF samples (83 PMNL negative and 20 PMNL positive) tested, the LE test performed well, especially in terms of specificity, specificity, and NPV. Particularly their high NPV value, make them a useful bedside screening tool, especially in the ambulatory setting such as outpatient clinics or in the emergency room, where the constraints of time and resources lead practitioners not to perform standard AF analysis. In patients with negative LE test, SBP, a disease having high mortality, can be ruled out with a high degree of certainty. Conversely, the satisfactory PPV of these strips substantiates the immediate start of appropriate antibiotic therapy in cases of positive testing, without any delay.

Vanbiervliet et al.[29] published the first study on the use of LER strip test in AF. They studied 72 consecutive patients with liver cirrhosis using Multistix 8 SG strips, the most frequently used urinary reagent strip in France and found the sensitivity and specificity of this test for the diagnosis of SBP to be 100% each. Since then, studies from different parts of the world have confirmed these results. The sensitivity of urinary reagent strips in these studies for the diagnosis of SBP has ranged between 85% and 100%, and the specificity between 98% and 100%.[30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37] In India, till date only two studies have been published on the use of LERS in AF. They reported the sensitivity and specificity as follows: Jha et al.[23] using multistix 10SG as 77.77% and 95.12% and Balagopal et al.[38] using Magistik-10 as 97% and 89%, respectively.

Sapey et al.[13] showed that different brands can achieve different accuracy in the diagnosis of SBP. The authors compared two different reagent strips (MultistixSG x Nephur-Test) finding that the Nephur-Test seems to out-perform Multistix SG. However, in another study conducted in both Europe and USA, the same authors did not find any difference between the two types of reagent strips.[33] Hence, we consider that further studies would be necessary to determine the best reagent strip brand that should be used for the prompt SBP diagnosis.

The limitations of the strip test include absence of a cut-off corresponding to cell count of 250 PMNL/mL in the reagent strip, and the possibility of inter-observer variation in matching of colour. Thus, it may be useful to confirm grade 2 colour changes with cell count. Further, it may be possible to manufacture modified test strips specifically for the diagnosis of SBP, such that colour change corresponds to a cut-off for 250 PMNL/mL of fluid.

CONCLUSION

Taking into account our results and those of the above-mentioned studies, we believe that the reagent strip could be a feasible option for a faster and cheaper diagnosis of SBP. The delay of SBP diagnosis is still frequent, mostly in hospitals with limited laboratory facilities, bringing serious consequences for life expectancy in cirrhotic patients. Thus, we should find a low-cost method that could be used anywhere and whose results could be readily available for a fast diagnosis of this infection. The good accuracy of this method along with its simplicity and the fact that it takes only 2 min to complete, makes it a promising diagnostic tool that could save lives by prompting early diagnosis and treatment of this life-threatening condition. However, it does not suggest that standard AF analysis be systematically replaced by the use of LER strips, but a positive result is surely an indicator for starting empirical antibiotic therapy, and a negative result excludes SBP with a high degree of certainty.

There is reasonable amount of evidence to support the use of LERS in the work-up of patients suspected of having SBP. Remote hospitals, less affluent health systems, and busy junior clinicians should realize the benefit of LERS and incorporate them in their AF handling routine. It is a kind of “new kid on the block” that has just appeared in the race against SBP; if further validation studies worldwide are supportive, it is set to become the mainstream process for handling AF samples with essentially no additional resources required.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amini M, Runyon BA. Alcoholic hepatitis 2010: A clinician's guide to diagnosis and therapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:4905–12. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i39.4905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ribeiro TC, Chebli JM, Kondo M, Gaburri PD, Chebli LA, Feldner AC. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: How to deal with this life-threatening cirrhosis complication? Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2008;4:919–25. doi: 10.2147/tcrm.s2688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rimola A, Garcia-Tsao G, Navasa M, Piddock LJ, Planas R, Bernard B, et al. Diagnosis, treatment and prophylaxis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: A consensus document. International Ascites Club. J Hepatol. 2000;32:142–53. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80201-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koulaouzidis A. Diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: An update on leucocyte esterase reagent strips. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:1091–4. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i9.1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thuluvath PJ, Morss S, Thompson R. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis--in-hospital mortality, predictors of survival, and health care costs from 1988 to 1998. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1232–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guarner C, Runyon BA. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: Pathogenesis, diagnosis and management. Gastroenterologist. 1995;3:311–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guarner C, Soriano G. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Semin Liver Dis. 1997;17:203–17. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines on the management of ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and hepatorenal syndrome in cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2010;53:397–417. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Runyon BA AASLD Practice Guidelines Committee. Management of adult patients with ascites due to cirrhosis: An update. Hepatology. 2009;49:2087–107. doi: 10.1002/hep.22853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moore KP, Wong F, Gines P, Bernardi M, Ochs A, Salerno F, et al. The management of ascites in cirrhosis: Report on the consensus conference of the International Ascites Club. Hepatology. 2003;38:258–66. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Runyon BA. Early events in spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Gut. 2004;53:782–4. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.035311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong CL, Holroyd-Leduc J, Thorpe KE, Straus SE. Does this patient have bacterial peritonitis or portal hypertension How do I perform a paracentesis and analyze the results? JAMA. 2008;299:1166–78. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.10.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sapey T, Kabissa D, Fort E, Laurin C, Mendler MH. Instant diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis using leukocyte esterase reagent strips: Nephur-Test vs. MultistixSG. Liver Int. 2005;25:343–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2005.01086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Devillé WL, Yzermans JC, van Duijn NP, Bezemer PD, van der Windt DA, Bouter LM. The urine dipstick test useful to rule out infections. A meta analysis of the accuracy. BMC Urol. 2004;4:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2490-4-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Azoulay E, Fartouk M, Galliot R, Baud F, Simonneau G, Le Gall JR, et al. Rapid diagnosis of infectious pleural effusions by use of reagent strips. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:914–9. doi: 10.1086/318140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Castellote J, Lopez C, Gornals J, Domingo A, Xiol X. Use of reagent strips for the rapid diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial empyema. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:278–81. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000155125.74548.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lopez Parades A, Valera Mortan C, Rodenas Garcia V, Pedromingo Marino A, Martínez Hernández P. The leukocyte zone on Multistix-10 SG reactive strips for cerebrospinal, seminal and peritoneal fluids. Med Clin (Barc) 1988;90:362–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wezyk MT, Makowski A, Krawczyk T. Cytological picture of fluid collected from middle ear in course of o. m. s. in children. Otolarynngol Pol. 2000;54:431–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Castellote J, López C, Gornals J, Tremosa G, Fariña ER, Baliellas C, et al. Rapid diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis by use of reagent strips. Hepatology. 2003;37:893–6. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garcia-Tsao G, Grace ND, Groszmann RJ, Conn HO, Bermann MM, Patrick MJ, et al. Short-term effects of propranolol on portal venous pressure. Hepatology. 1986;6:101–6. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840060119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marquette GP, Dillard T, Bietla S, Niebyl JR. The validity of the leukocyte esterase reagent test strip in detecting significant leukocyturia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;153:888–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(85)90696-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kutter D, Figueiredo G, Klemmer L. Chemical detection of leukocytes in urine by means of a new multiple test strip. J Clin Chem Clin Biochem. 1987;25:91–4. doi: 10.1515/cclm.1987.25.2.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jha AK, Kumawat DC, Bolya YK, Goenka MK. Multistix 10 SG leukocyte esterage dipstick testing in rapid bedside diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: A prospective study. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2012;2:224–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strasinger SK, Lorenzo MS. Chemical Examination of Urine. 5th ed. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis Company; 2008. Urinalysis and body fluids; pp. 53–80. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Triger DR, Smith JW. Survival of urinary leucocytes. J Clin Pathol. 1966;19:443–7. doi: 10.1136/jcp.19.5.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yong WH, Southern JF, Pins MR, Warshaw AL, Compton CC, Lewandrowski KB. Cyst fluid NB/70K concentration and leukocyte esterase: Two new markers for differentiating pancreatic serous tumors from pseudocysts. Pancreas. 1995;10:342–6. doi: 10.1097/00006676-199505000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beer JH, Vogt A, Neftel K, Cottagnoud P. False positive results for leucocytes in urine dipstick test with common antibiotics. BMJ. 1996;313:25. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7048.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scheer WD. The detection of leukocyte esterase activity in urine with a new reagent strip. Am J Clin Pathol. 1987;87:86–93. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/87.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vanbiervliet G, Rakotoarisoa C, Filippi J, Guérin O, Calle G, Hastier P, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of a rapid urine-screening test (Multistix 8SG) in cirrhotic patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14:1257–60. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200211000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sam R, Sahani M, Ulozas E, Leehey DJ, Ing TS, Gandhi VC. Utility of a peritoneal dialysis leuokocyte strip in diagnosis of peritonitis. Artif Organs. 2002;26:546–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1594.2002.06886_2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farmer CK, Hobbs H, Mann S, Newall RG, Ndawula E, Mihr G, et al. Leukocyte esterase reagent strips for early detection of peritonitis in patients on peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int. 2000;20:237–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thèvenot T, Cadranel JF, Nguyen-Khac E, Tilmant L, Tiry C, Welty S, et al. Diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhotic patients by use of two reagent strips. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:579–83. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200406000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sapey T, Mena E, Fort E, Laurin C, Kabissa D, Runyon BA, et al. Rapid diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis with leukocyte esterase reagent strips in a European and in an American center. J Gastroentetol Hepatol. 2005;20:187–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2004.03554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim DY, Kim JH, Chon CY, Han KH, Ahn SH, Kim JK, et al. Usefulness of urine strip test in the rapid diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Liver Int. 2005;25:1197–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2005.01176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wisniewski B, Rautou PE, Al Sirafi Y, Lambare-Narcy B, Drouhin F, Constantini D, et al. Diagnosis of spontaneous ascites infection in patient with cirrhosis reagent strips. Presse Med. 2005;34:997–1000. doi: 10.1016/s0755-4982(05)84098-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sarwar S, Alam A, Izhar M, Khan AA, Butt AK, Shafqat F, et al. Bedside diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis using reagent strips. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2005;15:418–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mendler MH, Agarwal A, Trimzi M, Madrigal E, Tsushima M, Joo E, et al. A new highly sensitive point of care screen for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis using the leukocyte esterase method. J Hepatol. 2010;53:477–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Balagopal SK, Sainu A, Thomas V. Evaluation of leucocyte esterase reagent strip test for the rapid bedside diagnosis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2010;29:74–7. doi: 10.1007/s12664-010-0017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]