Abstract

Seatbelt restraints are important for occupant safety which substantially reduces morbidity and mortality in severe motor vehicle crashes (MVC). Though, it has been established that the air bag and seatbelt use reduce injury severity and mortality but still there is limited information on the pattern of injury by restraint type. Herein, we presented two case reports which describe the injury pattern of two patients (both were restrained but only driver had airbag) involved in a single MVC. Both of them had severe traumatic injuries, however, the restrained passenger without airbag, sustained more severe injuries of intestine, kidney and spinal cord. In addition to seatbelt, airbag provides considerable protection against severe blunt abdominal trauma. Therefore, installation of airbags especially for front seat passenger is imperative for minimizing the risk of significant traumatic injuries.

Keywords: Abdominal trauma, airbag, injury pattern, motor vehicle crash, seatbelt

INTRODUCTION

Motor vehicle crashes (MVC) are the major cause of disability and deaths among adolescents and young population.[1] Particularly, the use of seatbelt is effective in minimizing the injury severity and outcomes after MVC. Many studies have demonstrated that seatbelt restraints are useful in reducing severe injuries by 45% to 55% and mortality by 43% to 50% in MVC.[2,3] These studies demonstrated the effectiveness of seatbelt use in reducing the incidence of head, face, abdomen and long bones injuries.[2] However, other investigators have observed higher frequency of abdominal wall herniation, hollow viscus, thoracic, and neck injuries in restraint individuals.[4,5] Abbas et al.[6] observed that injuries of spine, abdomen or pelvic region are mainly associated with seatbelt sign and such patients should be thoroughly evaluated to rule-out the occult intra-abdominal injuries. Chandler et al.[7] reported that out of 14 patients with an abdominal seatbelt sign, 9 sustained abdominal injuries. Airbags are supplemental tools that improve the effectiveness and safety of seatbelt during MVC. It helps to dissipate the crash impact over a greater surface area and prevent collision of the driver as well as passenger with the steering column, windshield, and dashboard. According to National highway Traffic Safety Administration, the air bag use alone decreased fatality by 13%, while combined use of air bag with a three-point seat belt, could potentially reduce the mortality by 50%.[8] Consistently, several investigators have demonstrated that the combined airbag and seat belt use significantly reduces the injury severity and mortality but still there is limited information on the pattern of injury by the restraint type. Herein, we describe the injury pattern of two patients (driver and passenger) in a single MVC, both were restrained but only driver had airbag as well.

CASE REPORT

There were 2 cases involved in the same MVC (driver and passenger).

The passenger

A 41- year old female, front-seat passenger restrain by seatbelt (no air bag), presented to our trauma center with grade IV shock, heart rate of 120 bpm, blood pressure of 80/45 mmHg, respiratory rate of 28 per min, oxygen saturation of 89%, and GCS of 14. Though, airway was clear, there was decreased air entry on left lateral side. Seat belt sign was noted over left chest and lower abdomen with degloving injury of lower abdomen and left lateral lumbar area. She also had a 15 cm laceration on left forehead with active bleeding, grade IV open fracture of the right distal radius with obvious transected right radial artery.

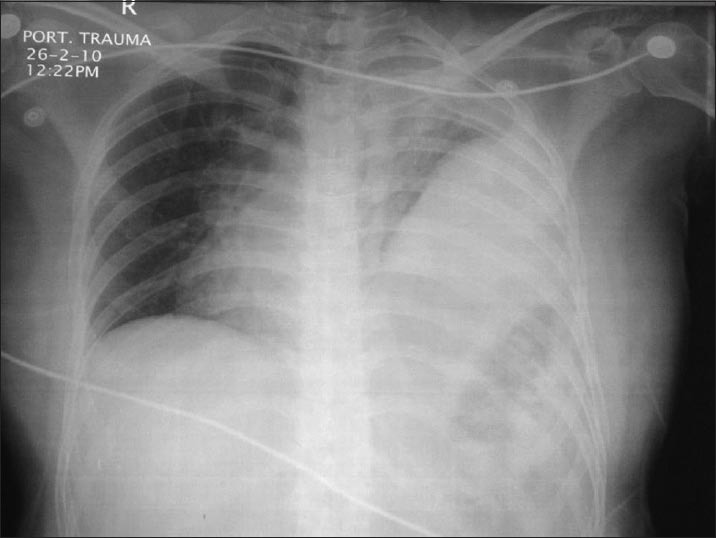

The patient was resuscitated with oxygen mask, crystalloid infusion and two units of ‘O’ negative (uncrossed match) PRBC in the trauma room and massive blood transfusion was activated. Focus Assessment with sonography of trauma (FAST) was positive, chest X-ray demonstrated herniation of abdominal content into the left pleural cavity [Figure 1] and pelvic X-ray was normal.

Figure 1.

Chest X-ray demonstrated herniation of abdominal content into the left pleural cavity (Patient 1; seatbelt without airbag)

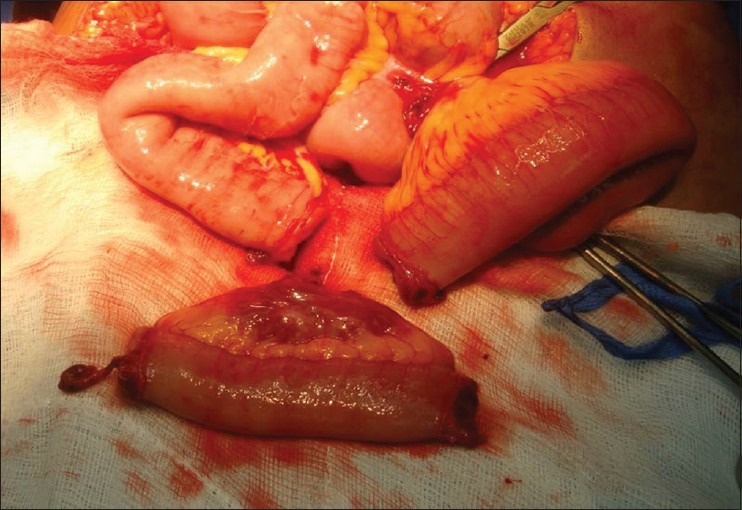

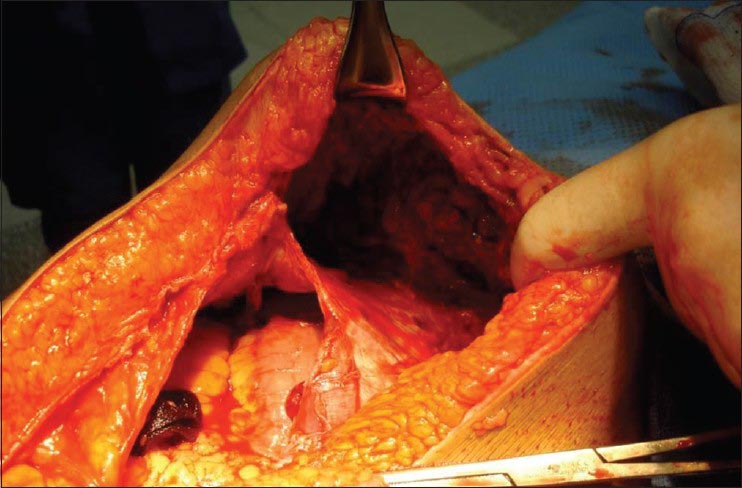

Patient was immediately transferred for exploratory laparotomy and found to have grade V left diaphragmatic rupture with significant left hemothorax, transected 10 cm of jejunum with its mesentery [Figure 2], and multiple bleeding mesenteric lacerations in mid small bowel and distal ileum. There was also a small paracecal hematoma, lacerated serosa of sigmoid colon with laceration of its mesentery, and small non-expanding retroperitoneal hematoma in left zone-2. Patient underwent diaphragmatic repair, irrigation of left hemothorax, left thoracostomy tube insertion and primary anastomosis of jejunum. A large soft tissue hematoma of (degloving/shearing injury) lower abdomen and left lateral lumbar areas were evacuated and drained with three large J-vac closed suction [Figure 3]. Right radial artery was ligated after positive triphasic Doppler signal of right ulnar artery, followed by external fixation of right radius, wound debridement and closure.

Figure 2.

Exploratory laparotomy showing grade V left diaphragmatic rupture with transaction of 10 cm of jejunum with its mesentery (patient 1)

Figure 3.

A large soft tissue hematoma of (degloving/shearing injury) lower abdomen and left lateral lumbar areas (Patient 1)

Patient was hemodynamically stable and was underwent head, chest and abdominal CT scan post-operatively. The CT findings revealed significant left lung contusion, fracture of left 10-11 ribs, fracture of 7th rib, non-perfused left kidney surrounded by small hematoma with thrombosed distal left renal artery, and unstable chance fracture of L2 with no cord compromise.

The patient maintained her vital signs after 12 hours with normalization of the acid-base balance. On tertiary trauma survey, patient was unable to move both lower limbs. Emergent MRI revealed congenital tethered spinal cord to the level of lower L2 with cord contusion extended from upper L1 to lower L2. X-ray of the extremities showed fractures of right lateral malleolus, 2nd and 3rd right metatarsal and query right talus, and fractured right foot 1st and 2nd phalanx, and fracture of right 5th MCB. She was extubated after 11 days; pedicle screw fixation was performed after 17 days with back brace applied for continuous physiotherapy, and she was able to walk normally after 2 months.

The driver

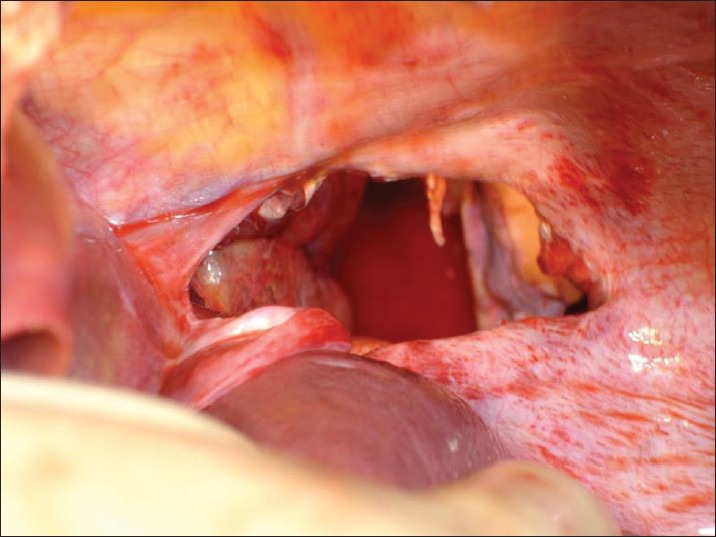

The second patient involved in the same MVC with the first patient was a male of 40 years old. This patient was using seatbelt and the airbag was working during the accident. He arrived with a stable hemodynamic status, GCS of 15, and decreased air entry to left lateral field of lung. He had seatbelt marks over his left chest and lower abdomen with moderate degloving injury of left lateral abdominal wall. Secondary survey revealed blood at the external urethral meatus, and had incidental right inguinal hernia. FAST was negative, fracture left mid femur, right radius, fibula and talus. Chest X-ray showed herniation of bowel to left hemi-thorax. CT scan demonstrated grade V left diaphragmatic injury with herniation of abdominal content into left hemothorax [Figure 4], bilateral lung contusions, suspicious of extravasated contrast from prostatic urethra. Patient was shifted to the operating room for repair of diaphragm, insertion of left thoracostomy tube and repair of mesenteric tear of ileocecal junction, rectosigmoid junction, and serosal tear of rectum [Figure 5]. He was extubated after 10 days; open reduction internal fixation for left femur was done after 12 days. The patient was doing well and transferred to trauma floor after 14 days.

Figure 4.

CT scan demonstrated grade V left diaphragmatic injury with herniation of abdominal content into left hemothorax (Patient 2; with airbag)

Figure 5.

Mesenteric tear of ileocecal junction, rectosigmoid junction, and serosal tear of rectum (Patient 2; with airbag)

DISCUSSION

The two cases presented in this series demonstrate the injury pattern among vehicle occupants within the same car and MVC. The driver used airbag and seatbelt whereas the front passenger used seatbelt only. Though, both patients had similar chest injuries, the patient with seat belt-only sustained more severe abdominal trauma and fracture of L2 with paraplegia. Consistent with our findings, Cummins et al.[9] has reported higher degree of protection in patients with seatbelt-plus-airbag in comparison to occupants who used seatbelts or airbags alone during the crash. In addition, Carter and Maker[10] found that the abdominal injuries were more frequent in patients wearing a seat belt than those who were unrestrained. The authors suggested that the sudden deceleration force applied to the mesentery could be the cause of mesenteric tear. Moreover, a retrospective analysis of abdominal injuries in restrained patients showed higher frequency of intestinal injuries with seat belt sign.[11] Denis et al.[12] showed that among 32 patients positive for seatbelt sign, 27 revealed bowel or mesenteric injuries by exploratory laparotomy. Other investigators have suggested that the presence of seatbelt sign had a 3-fold increased risk of intestinal perforations.[7,13].

Several studies have reported that the restrained patients are more likely to have mesenteric tears and rupture of the small bowel and colon. Specifically, perforations are more frequent in the jejunal and ileal bowel at the antimesentric borders, while rupture of the large intestine and duodenum are relatively uncommon.[13,14] Also, the transverse tears of the rectus abdominis muscle and anterior peritoneal tears are becoming more frequently recognized as part of the seat belt syndrome, which occurs immediately beneath the lap portion of the seat belt. This type of injury is frequently associated with hollow viscus injury and may provide a clue to the severity of injury.[15]

Furthermore, diaphragmatic ruptures have been reported in seat belt injuries, which could be secondary to faulty placement of the seatbelt or sliding of the occupant under the seatbelt during the early stages of impact. Such upward abdominal pressure from the seatbelt might leads to herniation of abdominal contents into the thoracic cavity.[16,17]

Matthes et al.[18] analyzed the likelihood of sustaining thoracic injury with or without a frontal airbag among car drivers. The authors found that airbag is associated with the risk of thoracic injury and there is significantly higher relative-risk of chest injuries among drivers with seatbelt-plus-frontal airbag.

Particularly, the injury to the spinal column is caused by shifting of the fulcrum to the anterior abdominal wall due to seat belt compression, thus producing distraction on all three columns (anterior, middle, and posterior) of the spine. However, these fractures showed little or no anterior compression of the involved vertebral body and the neurologic deficits are also infrequent. Moreover, in some cases the distractive forces causes only ligamentous disruption at the involved level, leading to a lumbar sublaxation or dislocation by using the shoulder-lap belt.[19] An earlier study reported that use of airbag alone or airbag plus seatbelt significantly reduces the risk of head, face, torso, and spinal injuries.[20] In addition, the authors observed that the severity of neck, abdomen, and upper extremity injuries were comparable among the restraints and non-restraint occupants. Though, various crash factors might influence the severity of injury but, the use of restraint type is usually associated with a specific pattern of injury in a specified body region. So in this series, we focused on the injury pattern of the blunt trauma in occupant protected by a seatbelt and airbag versus seatbelt alone in a single crash which could provide a better understanding of appropriate diagnosis of injuries which facilitate timely intervention.

In conclusion, although seatbelt and airbag have been proven to decrease severity of injury as well as mortality, both these tools is associated with specific injury pattern. Moreover, understanding the crash mechanism among patients with or without safety devices is useful for trauma surgeons for predicting the injury pattern, which guide the appropriate management. In this case report, in addition to seatbelt, airbag provides considerable protection against severe blunt abdominal trauma.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank all the trauma surgery staff for their cooperation. The authors have no conflict of interests and no financial issues to disclose. All authors read and approved the case report. This case report has been approved by the Medical Research Center (IRB no. 13295/13), Hamad Medical Corporation, Doha, Qatar.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.National highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA). Motor Vehicle Traffic Crashes as a Leading Cause of Death in the United States, 2008 and 2009. Traffic safety facts. 2012. [Last accessed 2014 March 05]. Available from: http://www-nrd.nhtsa.dot.gov/Pubs/811620.pdf .

- 2.Asbun HJ, Irani H, Roe EJ, Bloch JH. Intra-abdominal seatbelt injury. J Trauma. 1990;30:189–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Viano DC. Restraint effectiveness, availability and use in fatal crashes: Implications to injury control. J Trauma. 1995;38:538–46. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199504000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gutteridge I, Towsey K, Pollard C. Traumatic abdominal wall herniation: Case series review and discussion. ANZ J Surg. 2014;84:160–5. doi: 10.1111/ans.12079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Munshi IA, Patton W. A unique pattern of injury secondary to seatbelt-related blunt abdominal trauma. J Emerg Med. 2004;27:183–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abbas AK, Hefny AF, Abu-Zidan FM. Seatbelts and road traffic collision injuries. World J Emerg Surg. 2011;6:18. doi: 10.1186/1749-7922-6-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chandler CF, Lane JS, Waxman KS. Seatbelt sign following blunt trauma is associated with increased incidence of abdominal injury. Am Surg. 1997;63:885–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Highway Traffic Safety Administration: Fourth Report to Congress: Effectiveness of Occupant Protection Systems and Their Use. 1999. May, [Last accessed on 2014 March 06]. Available from: http://www.ntis.gov/search/product.aspx?ABBR=PB2001103424 .

- 9.Cummins JS, Koval KJ, Cantu RV, Spratt KF. Do seat belts and air bags reduce mortality and injury severity after car accidents? Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2011;40:E26–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carter PR, Maker VK. Changing paradigms of seat belt and air bag injuries: What we have learned in the past 3 decades. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210:240–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wotherspoon S, Chu K, Brown AF. Abdominal injuries and the seat-belt sign. Emerg Med (Fremantle) 2001;13:61–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2026.2001.00180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Denis R, Allard M, Atlas H, Farkouh E. Changing trends with abdominal injury in seatbelt wearers. J Trauma. 1983;23:1007–8. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198311000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Appleby JP, Nagy AG. Abdominal injuries associated with the use of seatbelts. Am J Surg. 1989;157:457–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(89)90633-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayes CW, Conway WF, Walsh JW, Coppage L, Gervin AS. Seat belt injuries: Radiologic findings and clinical correlation. Radiographics. 1991;11:23–36. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.11.1.1996397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnstone BR, Waxman BP. Transverse disruption of the abdominal wall: A tell-tale sign of seat belt related hollow viscus injury. Aust N Z J Surg. 1987;57:455–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1987.tb01397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Newman RJ. Chest wall injuries and the seat belt syndrome. Injury. 1984;16:110–3. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(84)80010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arajärvi E, Santavirta S. Chest injuries sustained in severe traffic accidents by seatbelt wearer. J Trauma. 1989;29:37–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matthes G, Schmucker U, Lignitz E, Huth M, Ekkernkamp A, Seifert J. Does the frontal airbag avoid thoracic injury? Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2006;126:541–4. doi: 10.1007/s00402-006-0181-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miniaci A, McLaren AC. Anterolateral compression fracture of the thoracolumbar spine. A seat belt injury. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;240:153–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cummins JS, Koval KJ, Cantu RV, Spratt KF. Risk of Injury Associated with the Use of Seat Belts and Air Bags in Motor Vehicle Crashes. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis. 2008;66:290–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]