Abstract

Setting realistic weight loss goals may play a role in weight loss. We abstracted data from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and observational studies conducted between 1998 and 2012 concerning the association of weight loss goals with weight loss. Studies included those that (i) were conducted in humans; (ii) delivered a weight loss intervention; (iii) lasted ≥6 weeks; (iv) assessed baseline weight loss goals; (vi) assessed pre and post weight either in the form of BMI or some other measure that could be converted to weight loss based on information included in the original study or later provided by the author(s); and (vii) assessed the correlation between weight loss goals and final weight loss or provided data to calculate the correlation. Studies that included interventions to modify weight loss goals were excluded. Eleven studies met inclusion criteria. The overall correlation between goal weight and weight at intervention completion was small and statistically insignificant (=0.05; p=0.20). The current evidence does not demonstrate that setting realistic goals leads to more favorable weight loss outcomes. Thus, our field may wish to reconsider the value of setting realistic goals in successful weight loss.

Keywords: weight loss goals, obesity, overweight, desired weight loss outcomes

Introduction

The percentage of Americans who are overweight or obese has substantially increased over the past half century1. Recent estimates indicate that 34% of the U.S. population is overweight and another 34% is obese1. The health consequences of overweight/obesity are numerous including increased risk of heart disease, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, stroke, and some cancers2. Given the aforementioned, it is not surprising that 1 in 3 adults repeatedly attempt to lose weight3, 4.

An important issue for those attempting to lose weight is determining an appropriate weight loss goal. Clinical recommendations suggest that a 10% reduction in body weight is an appropriate goal for treatment5, 6. This recommendation is based on evidence that a 10% reduction in body weight is both realistic for participants to achieve and is correlated with improvements in both physical and psychological health5, 7-9. However, a 10% reduction in weight is considered unsatisfactory by many individuals trying to lose weight7, 9, 10. In fact, participants enrolled in weight loss programs report wanting to lose 16% to 34% of their baseline weight7, 10-13, illustrating the discrepancy between current clinical guidelines and patients’ preferences.

In addition to the clinical benefits of modest weight loss, clinicians and researchers often advocate for a goal of 10% weight reduction based on the idea that less realistic goals are associated with less weight loss, attrition and negative psychological outcomes7, 10, 12, 14, 15. Patients are further encouraged to reach for realistic weight loss goals by popular, high traffic health websites such as Livestrong.com, which encourages individuals to “Set realistic goals that are actually achievable”16. Popular magazines have also supported setting realistic weight loss goals. For example, an article appeared in Diabetes Forecast, entitled: “Defining success. Realistic goals are key to staying motivated about weight loss.”17. In this article, individuals were encouraged to strive for modest weight goals, such as a 10% reduction in body weight.

Despite the popularity of encouraging overweight and obese individuals to set modest weight goals, the influence of weight loss goals on actual weight loss remains unclear. In fact, a handful of studies have reported that less realistic goals were actually associated with better weight loss outcomes12, 18, 19. Thus, the purpose of the current study was to systematically assess and integrate the available literature examining the relationship between weight loss goals and weight loss outcomes via meta-analysis. Findings from the study will provide further insight to the veracity of the popular statement that helping participants set realistic weight goals is important.

Methods

Identification of Studies

A literature search was performed in May 2012. Studies were identified by searching the databases of PubMed, PsycINFO, and Dissertation Abstracts. Search procedures located articles at the intersection of the key concepts of “weight loss goals” and “overweight population.” The union of keyword variations of each of these two concepts were queried during search procedures as indicated in Table 1. An example of a search iteration performed includes: “weight loss goals” AND “obese”.

Table 1.

The search strategy.

| Key Concept | Keywords, phrases, or descriptors |

|---|---|

| Weight Loss Goals | Weight loss goals OR Expected weight loss OR Desired weight loss OR |

| Overweight Population | Obese OR Obesity OR Overweight |

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria were:

Publication prior to May 2012

Minimum treatment and/or follow-up periods of six-weeks

Delivery of a weight loss intervention

Assessment of baseline weight loss goals

Assessment of pre and post weight either in the form of BMI or some other measure that could be converted to weight loss based on information included in the original study or later provided by the author(s)

Subjects were human subjects

Assessment of the correlation between weight loss goals and final weight loss or provision of data to calculate the correlation

Exclusion criteria were:

Studies that included modification of weight loss goals as an intervention

When two or more studies/papers relied on the same sample, all but the most recent works were excluded

Data Collection

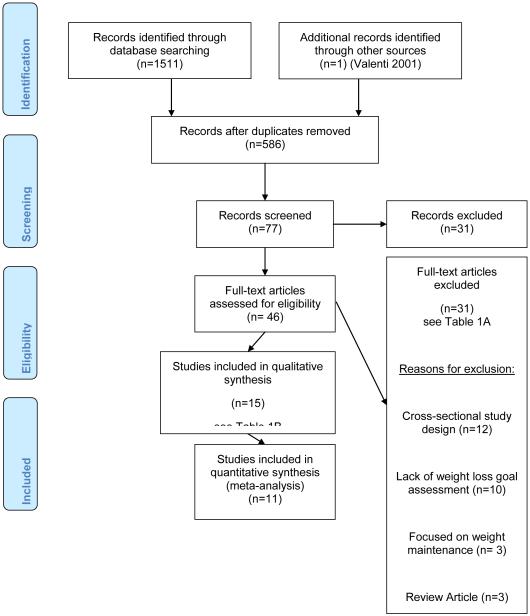

Data were independently abstracted by two reviewers and any disagreements on inclusion were resolved by the two reviewers to reach a consensus. In step 1 of data abstraction, titles of studies retrieved during search procedures were reviewed for eligibility. Abstracts of the studies with titles demonstrating possible eligibility were then reviewed. Finally, entire articles of studies with abstracts indicating eligibility were evaluated to determine whether the relationship between weight loss goals and weight loss at intervention completion could be assessed. After identification of studies meeting inclusion criteria, lead authors for all potential publications were sent both an email and hard copy communication to both verify information presented in the study and ask for clarification as well as any additional needed information. Figure 1 illustrates the data identification and abstraction process using a PRISMA flow diagram.

Figure 1.

Study screening and selection process.

Variables

Weight Loss Goals Variable

In this meta-analysis, the predictor of “weight loss goal” was defined as follows: weight or weight loss the individual aims to achieve at the end of the intervention. Based on the operational definitions of goals used within each study, we selected three different definitions for inclusion in the meta-analysis: 1) “happy weight” (i.e. a weight that you would be happy to achieve at the end of the intervention7), 2) “weight loss expected at the end of the intervention,” and 3) “weight the participant expects to lose at the end of the intervention”. Specifically in the analysis, for the following studies the “happy weight” was used: Texiera et. al. 200215, Foster et. al. 2004 27, White et. al. 2007 28 and White et. al. 2011 60. For the remainder of the studies, “weight loss goal/expected weight loss at the end of the intervention” was used in the analysis.

Some studies included in this review assessed additional weight loss goals (e.g. maximum acceptable weight loss goals and dream/ideal weight loss goals); however, these did not reflect the “weight the individual aims to achieve at the end of the intervention,” and thus, were not considered as predictors in the quantitative analyses.

Outcome

Weight loss at the end of the intervention was considered as the weight loss outcome in the quantitative analysis. Weight loss that occurred after interventions in follow up assessments was available in some studies. However, in this meta-analysis only the relationship between weight loss goal and weight loss at the end of the intervention was assessed.

Data analysis

Derivation of Correlations

The studies varied in their methodologies and reported statistics. In instances where the correlation coefficients () were not provided by the initial study or obtained through further communication with the study authors, () was computed according to various formulae, depending on the statistics available from the study20.

In each study, associations were analyzed for the study population as one group with the exception of Linde 200519 . In Linde et. al. 19 associations are calculated separately for men and women. In Fabricatore et. al.18, which included multiple therapy groups, the correlation between weight goals and weight loss is calculated based on the entire sample collapsed across treatment modality.

In Texeira 200215 and Texeira 200421, correlations between weight loss goals and outcomes were provided for both completers and the whole sample based the last observation carried forward method. For this analysis, the correlation for the completers analyses is used in the meta-analysis.

Meta-analysis

To summarize the associations across all studies, we converted the original correlation coefficients () using Fisher’s Ζ transformations and estimated the mean association for both fixed and random effects models. The Q statistic22 and the I2 index23 were also calculated to evaluate for heterogeneity for the fixed effect model (p<0.05 represents significant heterogeneity across studies). The associations for both models were back-transformed to produce the final summary () with corresponding 95% confidence interval. P-values were also computed. All analyses were conducted using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Software Version 224.

Results

Eleven studies met inclusion criteria. Figure 1 depicts the process for screening and selection of the studies. Tables 2A and 2B provide information of specific reasons for exclusion of studies from analyses. Table 3 provides descriptive information on the11 studies meeting inclusion criteria. The intervention duration of eligible studies ranged from 2 to 18 months. Participants of these studies were predominately middle-age females. A variety of weight loss interventions were tested in the studies, including: cognitive behavioral therapy, pharmacological methods, dietary modification and gastric bypass surgery. Regarding the study designs employed by the individual studies, five used a randomized controlled trial design, five used a single-group pre-post test design, one used a retrospective design, and one study was observational in nature.

Table 2A.

Full-text articles excluded with reasons (excluded based on inclusion/exclusion criteria).

| Reason for Exclusion | N | Articles Excluded |

|---|---|---|

| Cross Sectional Study Design | 12 | Williamson (1992)29

Cachelin (1998)30 Kottke (2002)31 Anderson (2003)32 Wadden (2003)33 Dutton (2004)34 Provencher (2007)11 Fabricatore (2008)35 Kaly (2008)36 Wamsteker (2009)37 Dutton (2010)38 Karmali (2011)39 |

| Did not assess weight goals | 10 | Bautista (2004)40

Knauper (2005)41 Albassam (2007)42 Williams (2007)43 Carels (2009)44 Zijlstra (2009)45 Angkoolpakdeedul (2011)46 Freund (2011)47 Paxman (2011)48 Wadden (2011)49 |

| Focused on weight maintenance | 3 | Byrne (2002)50

Finch (2005)13 Gorin (2007)51 |

| Review article | 3 | Miller (2001)52

Franz (2004)53 Crawford (2012)25 |

| Did not assess weight goals or have a weight loss intervention |

2 | Paxton (2004)54

de Ridder (2007)55 |

| Study included a cognitive intervention to modify weight loss goals not weight loss |

1 | Ames (2005)26 |

| Total | 31 |

Table 2B.

Articles excluded from meta-analysis after qualitative synthesis.

| Reason for Exclusion | N | Articles Excluded |

|---|---|---|

| Study included a cognitive intervention to modify weight loss goals |

1 | Wadden (2003)33 |

| Utilized a duplicate study sample as a more recently published study |

1 | Grave (2004)56 |

| Assessment of the correlation between weight loss goals and final weight loss not available and provision of data to calculate the correlation was not provided (requests sent by email and mail) |

2 | Foster (1997)7

Jeffery (1998)57 |

| Total | 4 |

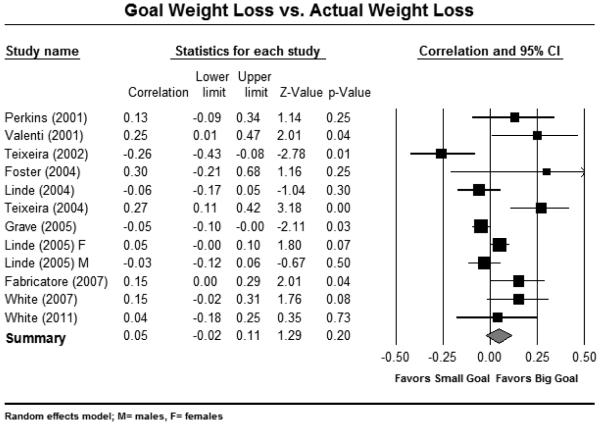

Meta-analysis

The forest plot represents the association for each study, the relative study weight, and the summary effect across the included studies (Figure 2). The overall correlation between goal weight and weight at intervention completion was small and statistically insignificant for both the fixed and random effects models (=0.01; p=0.66, =0.05; p=0.20 respectively). There was significant heterogeneity across studies (Q=40.82, df(Q)=11, p<0.001,); therefore only the data from the random effects model are shown.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of studies assessing goal weight loss versus actual weight loss.

Discussion

This meta-analysis evaluated the evidential basis for the common view espoused by clinicians and researchers that unrealistic weight loss goals may be counterproductive in terms of weight loss. We conducted a rigorous systematic search of the literature to identify studies that assessed weight loss goals and weight loss outcomes. Eleven studies met inclusion criteria. Studies had a predominance of women. Results of the meta-analysis revealed no statistically significant relationship of weight loss goals to weight loss outcomes. To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis on this topic.

We identified one systematic review conducted by Crawford and Glover25 that asserted the relationship of weight loss goals to weight loss was unclear due to the diversity of the included studies. In our study, there was significant heterogeneity across studies. However, the overall correlation between goal weight and weight at intervention completion was small and statistically insignificant for both the fixed and random effects models.

Intervention studies conducted to alter patients’ unrealistic goals in order to improve weight loss lend further support to the results of this study26, 27. Specifically, while these modified programs produced significant changes in weight loss expectations (such that patients’ goals became more realistic), these interventions did not result in greater weight loss, weight loss maintenance, or better psychological outcomes (e.g., depressive symptoms, self-esteem). Results from these studies further support the conclusion that unrealistic goals are not meaningfully related to actual weight loss achieved or other outcomes of interest.

A potential limitation in assessing data for the association of weight loss goals and weight loss outcomes across multiple studies is the diversity of terminology used when referring to weight loss goals. We found that different studies assessed the questions in different ways (Table 3). Our choice of one predictor, the “weight loss goal” defined as: “weight or weight loss the individual aims to achieve at the end of the intervention,” is an attempt to standardize the predictor across studies included in the analyses. Other weight loss goals assessed (e.g. maximum acceptable weight loss goals and dream/ideal weight loss goals) that did not reflect the “weight the individual aims or aims to achieve at the end of the intervention” were considered beyond the scope of this work. Researchers conducting future studies should attempt to establish a standardized method in which to assess weight loss goals to assist in the evaluating the association between weight goals and actual weight loss across studies. Use of a survey such as the Goals and Relative Weights Questionnaire developed by Foster et al.7 may show promise for establishing a standardized method. Another potential limitation of the study is that we included studies with participants who underwent bariatric weight loss. The possibility exists that these participants may have had different weight loss goals than those not seeking surgery (e.g. greater weight loss goal), and the discrepancy between goals and likely outcomes may differ for patients undergoing this procedure as compared to non-surgical interventions. Lastly, our study findings only address the active phase of weight loss. Our findings do not address the role of weight loss goals in maintenance of weight loss. Recent studies have proposed that behaviors important in weight loss vs. weight maintenance may differ. The role of weight loss goals in long-term outcomes is an important topic for future study.

While other goals were not used in this analysis, we acknowledge that they are frequently referred to in the literature as support for or against the notion that realistic goals are associated with weight loss success. Results of several of the studies included in this meta-analysis did support the notion that less realistic “dream or ideal goals” are associated with positive weight loss outcomes.12, 28 In Linde et. al. 2004,12 there was an association between higher dream weight losses and greater weight loss at follow-up at 18 months. Again, this is a different concept and thus should be explored separately in analyses that examine the role of “ideal” or “dream” goals in weight loss, as it is possible that a different pattern may emerge between these goals and weight loss outcomes.

While the assertion that unrealistic goals lead to disappointment and discontinuation of weight loss efforts makes intuitive sense, the empirical evidence does not support this conclusion. While it is ethically imperative that weight loss program participants are not misled about the typical outcomes achieved in treatment, efforts to dispel patients’ potentially unrealistic goals seems unjustified based on the lack of observed association between patients’ goals and weight loss outcomes.

Table 3.

Descriptive information on the studies included.

| Authors | Baseline Sample Characteristics |

Design/Intervention | Treatment Duration/Follow-up Assessmentsa |

Weight Loss Goals Assessed |

Relationship of Weight Loss Goal and Follow- up BMIc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perkins (2001)58 |

N=79 (57 females) Mean age 46 years Mean BMI 42.1 kg/m2 Note: N breakdown was calculated by percentages ; the % of that sample that was female was 72.7 |

Retrospective study utilizing survey/medical record extraction among patients of an outpatient endocrinology clinic who had been diagnosed with obesity |

Treatment: Varied according to the individual Follow-up: Non-time limited program |

Goal Weight:

Desired weight at the end of treatment (Weight individual expects to achieve at the end of the intervention) |

No association between weight loss goal and weight loss at the end of the intervention. |

| Valenti (2001)59 |

N=88 females Mean age 48.0 years Mean BMI 33.2 kg/m2 |

Three group randomized weight loss trial consisting of varying combinations of behavioral therapy, resistance training, and aerobic walking |

Treatment: 6 months Follow-up: 6 months |

Goal Weight:

Weight individual expects to achieve at the end of the intervention |

Higher weight loss goal associated with greater weight loss at the end of the intervention. |

| Teixeira (2002)15 |

N=112 females Mean age 47.8 years Mean BMI 31.4 kg/m2 |

One group pre/post test design evaluating the effects of a group- based behavioral therapy weight loss program |

Treatment: 4 months Follow-up: 4 months |

Goals from Part II of the GRWQ b |

No association between weight loss goal (happy weight) and weight loss at the end of the intervention (completers analysis; used in meta analysis) Lower weight loss goals related to more weight loss in the last observation carried forward method analysis only |

| Foster (2004)27 |

N=17 females Mean age 46.5 years Mean BMI 34 kg/m2 |

One-group pre-post design assessing the effects of a modified cognitive behavioral therapy program promoting modest weight goals and weight loss |

Treatment: 20 weeks Follow-up : 40 weeks |

Goals from Part II of the GRWQ b |

No association between weight loss goal (happy weight) and weight loss at the end of the intervention |

| Linde (2004)12 |

N=302 (mostly female) Mean age 46.7 years Mean BMI 33.9 kg/m2 |

Randomized clinical trial of cognitive interventions designed to influence outcome expectations associated with weight loss |

Treatment: 8 weeks Follow-up: 8 weeks; 6, 18 months |

Adapted goals from the GRWQb Goal Weight: Weight expected at the end of program Dream Weight: A weight you would choose if you could weigh whatever you wanted |

No association between weight loss goal and weight loss at the end of the intervention (Note: Higher dream weight loss goals were associated with greater weight loss at 18 month follow up) |

| Teixeira (2004)21 |

N=140 females Mean age 38.3 Mean BMI 30.3 kg/m2 |

One-group pre-post design assessing the effects of a group- based behavioral therapy weight loss program |

Treatment: 4 months Follow-up: 4 months |

Goals from Part II of the GRWQb |

No association between weight loss goal (happy weight) and weight loss at the end of the intervention (completers analysis; used in meta analysis) Higher weight loss goals associated with less weight loss in the last observation carried forward method analysis only |

| Grave (2005)14 | N= 1785 (1393 females) Median age 46.0 years Median BMI 36.7 kg/m2 |

Observational study investigating quality of life in obese patients seeking treatment in 25 Italian medical centers |

Treatment: Duration varied according to medical center; Patients assessed at 12 months Follow-up: N/A |

Expected 1 year

weight loss(Goal Weight): Weight loss patients expected to lose with treatment after 12 months Maximum acceptable weight: Heaviest weight that patients could accept and tolerate to reach after treatment Dream weight: Body weight that the patient dreams of achieving with treatment |

No association between weight loss goal and weight loss at the end of the intervention (Note: Higher dream weight loss goals were associated with less weight loss at the end of the intervention.) |

| Linde (2005)19 | N=1801 (1293 females, 508 males) Mean female age 49.97 years Mean male age 54.14 years Mean female BMI 33.86 kg/m2 Mean male BMI 33.10 kg/m2 |

Randomized control weight loss trial (three groups: mail, phone, usual care) |

Treatment: 12 months Follow-up: 12 months, 24 months |

Goal Weight:

Weight individual expects to achieve at the end of the Weigh to Be Intervention Ideal Weight: Weight participants would like to weigh |

No association between weight loss goal and weight loss at the end of the intervention for males or females. Higher weight loss goals were associated with greater weight loss at 24 month follow up in women only |

| Fabricatore (2007)18 |

N=180 (149 females, 31 men) Mean age 43.8 years Mean BMI 37.6 kg/m2 |

Four group randomized trial consisting of varying combinations of behavioral and pharmacological therapies |

Treatment: 52 weeks Follow-up: 4, 12, 26 and 52 weeks |

Expected Loss

(Goal weight): Weight individual expects to achieve at the end of the intervention Ultimate Goal: Weight expected to lose in total, whether or not it can be achieved |

No association between weight loss goal and weight loss at the end of the e intervention in the collapsed sample |

| White (2007)28 | N=139 (123 females) Mean age 42.4 years Mean BMI 57.79 kg/m2 |

One-group pre-post design among bariatric surgery candidates |

Treatment: Gastric bypass surgery Follow-up 6, 12 months ( For analyses, 12 month period considered the “end of the intervention”) |

Goals from Part II of the GRWQb |

No association between weight loss goal (happy weight) and weight Loss at the end of the intervention (Note: Lower acceptable weight loss goals were associated with greater weight loss at 12 months) |

| White (2011)60 | N=84 African American females Mean age 49 years Mean BMI 37 kg/m2 |

One-group pre-post design assessing the effects of group behavioral weight loss intervention |

Treatment: 6 months. Follow-up: 6 months |

Goals from Part II of the GRWQb: |

No association

between weight loss goal(happy weight) and weight loss at the end of the intervention |

Follow-up assessments are post-baseline.

Part II of the Goals and Relative Weight Questionnaire (GRWQ); 7 assesses the following weight goals: Dream Weight: A weight you would choose if you could weigh whatever you wanted; Happy Weight: This weight is not as ideal as the first one [dream]. It is a weight, however, that you would be happy to achieve; Acceptable Weight: A weight that you would not be particularly happy with, but one that you could accept, since it is less that your current weight; Disappointed Weight: A weight that is less than your current weight, but one that you could not view as successful in any way. You would be disappointed if this were your final weight after the program

Results reported are for all treatment groups collapsed (when applicable) unless otherwise specified.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by NIH Grant P30DK056336.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: Dr. Allison reports that he has received grants, honoraria, donations, and consulting fees from numerous food, beverage, and pharmaceutical companies, and other commercial and nonprofit entities with interests in obesity, including but not limited to Medifast, Vivus, and Arena.

References

- 1.Prevention CfDCa U.S. Obesity Trends. 2011 http://www.cdc.gov/obsity/data/trends.html.

- 2.Services. UDoHaH Obesity and African Americans. 2011 http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/templates/content.aspx?ID=6456.

- 3.Kruger J, Galuska DA, Serdula MK, Jones DA. Attempting to lose weight: specific practices among U.S. adults. Am J Prev Med. 2004;26:402–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paeratakul S, York-Crowe EE, Williamson DA, Ryan DH, Bray GA. Americans on diet: results from the 1994-1996 Continuing Survey of Food Intakes by Individuals. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102:1247–51. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90276-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Heart L. Blood Institute . Clinical Guidelines on the Identifcation, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults. National Institute of Health; Bethesda, MD: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Health. NIo . The practical guide: Identifcation, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults. National Institute of Health; Bethesda, MD: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foster GD, Wadden TA, Vogt RA, Brewer G. What is a reasonable weight loss? Patients' expectations and evaluations of obesity treatment outcomes. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65:79–85. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blackburn G. Effect of degree of weight loss on health benefits. Obes Res. 1995;3(Suppl 2):211s–16s. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1995.tb00466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foster GD, Kendall PC. The Realistic Treatment of Obesity: Changing the Scale of Success. Clinical Psychology Review. 1994;14:701–36. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foster GD, Wadden TA, Phelan S, Sarwer DB, Sanderson RS. Obese patients' perceptions of treatment outcomes and the factors that influence them. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:2133–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.17.2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Provencher V, Bégin C, Gagnon-Girouard MP, Gagnon HC, Tremblay A, Boivin S, et al. Defined weight expectations in overweight women: Anthropometrical, psychological and eating behavioral correlates. International Journal of Obesity. 2007;31:1731–38. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Linde JA, Jeffery RW, Finch EA, Ng DM, Rothman AJ. Are unrealistic weight loss goals associated with outcomes for overweight women? Obes Res. 2004;12:569–76. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finch EA, Linde JA, Jeffery RW, Rothman AJ, King CM, Levy RL. The effects of outcome expectations and satisfaction on weight loss and maintenance: Correlational and experimental analyses-a randomized trial. Health Psychology. 2005;24:608–16. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.6.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dalle Grave R, Melchionda N, Calugi S, Centis E, Tufano A, Fatati G, et al. Continuous care in the treatment of obesity: an observational multicentre study. J Intern Med. 2005;258:265–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2005.01524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Teixeira PJ, Going SB, Houtkooper LB, Cussler EC, Martin CJ, Metcalfe LL, et al. Weight loss readiness in middle-aged women: psychosocial predictors of success for behavioral weight reduction. J Behav Med. 2002;25:499–523. doi: 10.1023/a:1020687832448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Myers HR. Weight Loss Goal Setting. 2011 www.livestrong.com/article/368047-weight-loss-goal-setting/ [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roberts SS. Defining success. Realistic goals are key to staying motivated about weight loss. Diabetes Forecast. 2004;57:54–5. 52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fabricatore AN, Wadden TA, Womble LG, Sarwer DB, Berkowitz RI, Foster GD, et al. The role of patients' expectations and goals in the behavioral and pharmacological treatment of obesity. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31:1739–45. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Linde JA, Jeffery RW, Levy RL, Pronk NP, Boyle RG. Weight loss goals and treatment outcomes among overweight men and women enrolled in a weight loss trial. Int J Obes (Lond) 2005;29:1002–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolf FM. Meta-Analysis: Quantitative Methods for Research Synthesis. SAGE Publications; Beverly Hills, CA: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Teixeira PJ, Going SB, Houtkooper LB, Cussler EC, Metcalfe LL, Blew RM, et al. Pretreatment predictors of attrition and successful weight management in women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28:1124–33. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cochran WG. The Combination of estimates from different experiments. Biometrics. 1954;10:101–29. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–58. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borgstein M, Hedges L, Higgins J, Rothestein H. Comprehensive meta-analysis version 2. Englewood, NJ; Biostat: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crawford R, Glover L. The impact of pre-treatment weight-loss expectations on weight loss, weight regain, and attrition in people who are overweight and obese: a systematic review of the literature. Br J Health Psychol. 2012;17:609–30. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8287.2011.02059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ames GE, Perri MG, Fox LD, Fallon EA, De Braganza N, Murawski ME, et al. Changing weight-loss expectations: A randomized pilot study. Eating Behaviors. 2005;6:259–69. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Foster GD, Phelan S, Wadden TA, Gill D, Ermold J, Didie E. Promoting more modest weight losses: a pilot study. Obes Res. 2004;12:1271–7. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.White MA, Masheb RM, Rothschild BS, Burke-Martindale CH, Grilo CM. Do patients' unrealistic weight goals have prognostic significance for bariatric surgery? Obes Surg. 2007;17:74–81. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Williamson DF, Serdula MK, Anda RF, Levy A, Byers T. Weight loss attempts in adults: goals, duration, and rate of weight loss. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:1251–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.9.1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cachelin FM, Striegel-Moore RH, Elder KA. Realistic weight perception and body size assessment in a racially diverse community sample of dieters. Obes Res. 1998;6:62–8. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1998.tb00316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kottke TE, Clark MM, Aase LA, Brandel CL, Brekke MJ, Brekke LN, et al. Self-reported weight, weight goals, and weight control strategies of a midwestern population. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77:114–21. doi: 10.4065/77.2.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anderson DA, Lundgren JD, Shapiro JR, Paulosky CA. Weight goals in a college-age population. Obes Res. 2003;11:274–8. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wadden TA, Womble LG, Sarwer DB, Berkowitz RI, Clark VL, Foster GD. Great Expectations: "I'm Losing 25% of My Weight No Matter What You Say". Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:1084–89. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.6.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dutton GR, Martin PD, Brantley PJ. Ideal weight goals of African American women participating in a weight management program. Body Image. 2004;1:305–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fabricatore AN, Wadden TA, Rohay JM, Pillitteri JL, Shiffman S, Harkins AM, et al. Weight loss expectations and goals in a population sample of overweight and obese US adults. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16:2445–50. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaly P, Orellana S, Torrella T, Takagishi C, Saff-Koche L, Murr MM. Unrealistic weight loss expectations in candidates for bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4:6–10. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2007.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wamsteker EW, Geenen R, Zelissen PM, van Furth EF, Iestra J. Unrealistic weight-loss goals among obese patients are associated with age and causal attributions. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:1903–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dutton GR, Perri MG, Stine CC, Goble M, Van Vessem N. Comparison of physician weight loss goals for obese male and female patients. Prev Med. 2010;50:186–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karmali S, Kadikoy H, Brandt ML, Sherman V. What is my goal? Expected weight loss and comorbidity outcomes among bariatric surgery patients. Obes Surg. 2011;21:595–603. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-0060-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bautista-Castaño I, Molina-Cabrillana J, Montoya-Alonso JA, Serra-Majem L. Variables predictive of adherence to diet and physical activity recommendations in the treatment of obesity and overweight, in a group of Spanish subjects. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28:697–705. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Knauper B, Cheema S, Rabiau M, Borten O. Self-set dieting rules: adherence and prediction of weight loss success. Appetite: England. 2005:283–8. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Albassam RS, Abdel Gawwad ES, Khanam L. Weight management practices and their relationship to knowledge, perception and health status of Saudi females attending diet clinics in Riyadh city. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2007;82:173–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Williams CL, Strobino BA, Brotanek J. Weight control among obese adolescents: a pilot study. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2007;58:217–30. doi: 10.1080/09637480701198083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carels RA, Wott CB, Young KM, Gumble A, Darby LA, Oehlhof MW, et al. Successful weight loss with self-help: a stepped-care approach. J Behav Med. 2009;32:503–9. doi: 10.1007/s10865-009-9221-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zijlstra H, Larsen JK, de Ridder DT, van Ramshorst B, Geenen R. Initiation and maintenance of weight loss after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. The role of outcome expectation and satisfaction with the psychosocial outcome. Obes Surg. 2009;19:725–31. doi: 10.1007/s11695-008-9572-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Angkoolpakdeekul T, Vitoopinyopaab K, Lertsithichai P. Short-term outcomes of two laparoscopic bariatric procedures. J Med Assoc Thai. 2011;94:704–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Freund AM, Hennecke M. Changing eating behaviour vs. losing weight: The role of goal focus for weight loss in overweight women. Psychol Health. 2011 doi: 10.1080/08870446.2011.570867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Paxman JR, Hall AC, Harden CJ, O'Keeffe J, Simper TN. Weight loss is coupled with improvements to affective state in obese participants engaged in behavior change therapy based on incremental, self-selected "Small Changes". Nutr Res. 2011;31:327–37. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2011.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wadden TA, Neiberg RH, Wing RR, Clark JM, Delahanty LM, Hill JO, et al. Four-year weight losses in the Look AHEAD study: factors associated with long-term success. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011;19:1987–98. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Byrne SM. Psychological aspects of weight maintenance and relapse in obesity. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:1029–36. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00487-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gorin AA, Pinto AM, Tate DF, Raynor HA, Fava JL, Wing RR. Failure to meet weight loss expectations does not impact maintenance in successful weight losers. Obesity. 2007;15:3086–90. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miller WC. Effective diet and exercise treatments for overweight and recommendations for intervention. Sports Med. 2001;31:717–24. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200131100-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Franz MJ. Effectiveness of weight loss and maintenance interventions in women. Curr Diab Rep. 2004;4:387–93. doi: 10.1007/s11892-004-0042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Paxton RJ, Valois RF, Drane JW. Correlates of body mass index, weight goals, and weight-management practices among adolescents. J Sch Health. 2004;74:136–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2004.tb06617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.de Ridder D, Kuijer R, Ouwehand C. Does confrontation with potential goal failure promote self-regulation? Examining the role of distress in the pursuit of weight goals. Psychology & Health. 2007;22:677–98. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dalle Grave R, Calugi S, Magri F, Cuzzolaro M, Dall'aglio E, Lucchin L, et al. Weight loss expectations in obese patients seeking treatment at medical centers. Obes Res. 2004;12:2005–12. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jeffery RW, Wing RR, Mayer RR. Are smaller weight losses or more achievable weight loss goals better in the long term for obese patients? J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66:641–5. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.4.641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Griffith-Perkins SJ. Correlates of weight loss attainment and satisfaction with weight in patients referred for individualized obesity treatment. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering Vol. 2001:62. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Valenti NL. The relationship between expectations and actual attainments in a weight loss program. School of Psychology. Fairleigh Dickinson University: Proquest Dissertation and Theses. 2001:157. [Google Scholar]

- 60.White DB, Bursac Z, Dilillo V, West DS. Weight loss goals among African-American women with type 2 diabetes in a behavioral weight control program. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011;19:2283–5. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]