Abstract

Dentistry is neither an allied health profession nor a paramedical profession. It is the only anatomically focused health care profession that is university-based and for which primary care responsibility is maintained by the profession. Dentists must have a reliable knowledge of basic clinical medicine for safely and effectively treating individuals with chronic and other diseases, which make them biologically and pharmacologically compromised. With changes in the life expectancy of people and lifestyles, as well as rapid advancement in biomedical sciences, dentists should have similar knowledge like a physician in any other fields of medicine. There are number of primary care activities that can be conducted in the dental office like screening of diabetics, managing hypertension etc., The present review was conducted after doing extensive literature search of peer-reviewed journals. The review throws a spotlight on these activities and also suggests some the measures that can be adopted to modify dental education to turn dentists to oral physicians.

Keywords: Dentistry, disease, education, physician, primary care

Introduction

Primary care at its most root definition is medical care delivered with the patient and the community in mind. Traditionally, it is the first point of contact a person has with the health system; the point where people receive care for most of their everyday health needs.[1] Primary care in typically provided by family physicians, nurses, dieticians, mental health professionals, pharmacists, therapists, and others. However, central to the concept of primary care is the patient.[2] Primary care includes health promotion, disease prevention, health maintenance, counseling, patient education, diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic illnesses in a variety of health care settings (e.g., office, inpatient, critical care, long-term care, home care, day care, etc.).[3] It provides patient advocacy in the health care system to accomplish cost-effective care by coordination of health care services.

The dental profession is responsible for the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of diseases and disorders of the oral cavity and related structures. But, the overarching question is what role dental professionals will fill about the general health and well-being of patients under their care. As the population ages and chronic illnesses affect a large percentage of those seeking and requiring dental services, will the dental profession be prepared to comprehensively treat these kinds of patients?[4] Dentists have always cared for more than their patients’ teeth, but only in recent decades have researchers begun to establish the effectiveness of doing procedures in a dental office that have traditionally been limited to medical clinics.[5] Health care in neglected population can be improved by increasing the utilization of existing health care providers, particularly dentists, an opportunity that has been largely ignored.[6,7] They can then serve as oral physicians who can provide limited preventive primary care, including screening for chronic diseases, while continuing to oversee all dental care, whether provided by dentists or nondentists.[6]

An extensive review of the literature search was done (electronic and manual) which engaged most of the articles published in peer-reviewed journals relating to the subject of primary care in dentistry. The review itself began with the search of relevant key words linked with the dental and medical profession like primary care, dental health, dental office, dentistry, oral physicians etc. in various search engines including PubMed, MEDLINE, etc. Reports published only in English language were included in the review. The spotlight of the present review would not only be on primary care interventions which can be performed in the dental clinic or office but also on the modification of dental education curriculum. The review also targeted status of primary care in the dental profession in India and willingness of the Indian dentists to perform primary care procedures.

Dentistry and Systemic Health

Patient evaluation and diagnosis are essential to the practice of dentistry. For too long, the mouth has been considered separate from the rest of the body. The more we study this, the more we realize all the important connections there are. Evaluation of a patient's health status determines how systemic illnesses can modify oral, dental, and craniofacial diseases and the patient's ability to tolerate dental treatment.[8] The health care environment, including dentistry, is evolving. The population is aging, patients are retaining their teeth, edentulism is declining, and more people with multiple chronic diseases are seeking dental care.[9] With a growing body of knowledge suggesting that the oral infection and the associated tissue inflammation may affect diseases and conditions, there is an increased emphasis on the importance of oral diseases in the context of systemic health.[10]

The Dentist as “Oral Physician”

While recognition of the need to diagnose and treat the ever-increasing number of aging dental patients with more complex health care problems has certainly called attention to the need for dentists and other paramedical professionals to broaden their role in the delivery of overall health care, the designation as oral physician has not been endorsed universally.[6] Dentists are in an ideal position to assume an expanded role in providing limited preventive primary care. Dentists are already de facto oral physicians trained in many of the required medical and surgical skills, often see patients who do not have any other primary care provider, and typically schedule frequent return visits. Dental training already includes the ability to recognize more than 100 manifestations of genetic disorders, systemic disease, and lifestyle problems.[11] Dentists also have sufficient training to provide some aspects of preventive primary care such as taking, or supervising the delegation of taking vital signs to others, and administering vaccines or supervising others in doing so.[12]

The Dental Office: A Portal to Primary Care

As we contemplate the role of dentistry in primary care, it is a known fact that the practice of general dentistry is primary care. Dental clinic or office can serve as an excellent location for screening of many chronic diseases. The potential public health impact of using the dental office as a portal for primary care has been studied in relation to a rapidly growing health concerns: Diabetes mellitus and smoking. A study was carried out recently to determine the attitudes of patients attending routine appointments at primary care dental clinics and general dental practices toward the possibility of chair-side screening for medical conditions, including diabetes, in the dental setting.[13] Overall, 87% of respondents thought that it was important or very important that dentists screened patients for medical conditions like diabetes. The majority of respondents supported the concept of medical screening in a dental setting and were willing both to have screening tests and discuss their results with the dental team.[13] Reports of another study conducted on dental teams involved in primary care revealed that they were aware of the importance of offering smoking cessation advice and with further training and appropriate remuneration, could guide many of their patients who smoke to successful quit attempts.[14] Patient acceptance is paramount for successful implementation of such programs.

Primary Health Care Screenings and Interventions in the Dental Office

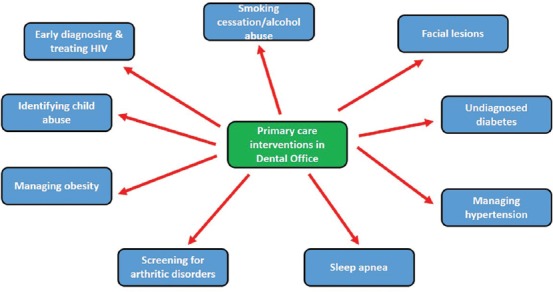

Primary care in the dental office should begin by focusing on activities that directly impact the provision of oral health [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Various primary care procedures that can be conducted in dental office

Smoking cessation and alcohol screening

Cigarette smoking is considered as a major risk factor for oral squamous cell carcinoma and periodontal disease. Smoking cessation programs in which dentists explain the importance of cessation for oral and dental health and general health should be part of regular dental care.[15,16] Dentists who implement an effective smoking cessation program can expect to achieve quit rates up to 10–15% each year among their patients who smoke or use smokeless tobacco.[17] Similarly, screening for alcoholic abuse/dependence can be done in the dental office as significant numbers of patients in dental office suffer from alcohol abuse/dependence.[18]

Facial lesions

Dental practitioners should be keen observers of the status of patients who come for dental treatment. Any unusual or adverse findings should be questioned or pursued. Examples are dermatologic lesions on the face, head, and other exposed skin surfaces and various allergic reactions that may be encountered in the dental office.[19] Premalignant and malignant lesions of the face, head, and neck are best treated early to avoid disfiguring surgery required for more advanced stages of disease. Examination of the patient's face and other skin surfaces can be achieved using the light in the dental operatory.[15,20]

Undiagnosed diabetes

Diabetes is the only systemic disorder that has been definitively identified as a risk factor for periodontal disease. Potentially, screening of patients for suspected diabetes can be made by using chair-side tests for blood glucose or glycosylated hemoglobin.[21]

Managing hypertension

Prevalence of hypertension is high, and dentists have been encouraged to participate in screening for hypertension for more than 30 years.[22] According to a survey conducted among dental hygienists, majority of the participants indicated that they rarely or never recorded blood pressure of their patients.[23] Based on these findings, a recommendation was made for dental offices to modify their patient check-in procedures to include recording blood pressure.

Sleep apnea

The role of dentistry in sleep disorders is becoming more significant, especially in co-managing patients with simple snoring and mild to moderate obstructive sleep apnea.[24] Sleep apnea is a problem that may be first recognized in the dental office. Dentists can be very involved in treating these patients. This care can involve mandibular advancement appliances and surgery to remove portions of the soft palate and uvula.[21]

Screening for osteoporosis and arthritic disorders

Both musculoskeletal disorders and diseases of the oral cavity are common and potentially serious problems among older persons. Several musculoskeletal diseases, including osteoporosis, Paget's disease, and arthritic disorders, may directly involve the oral cavity and contiguous structures.[25] Considerable evidence indicates that the density of the mandibular bone is related to general bone loss. The gold standard for assessment of skeletal bone universal density is dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, but dental radiographs, and in particular panoramic films, may be helpful in directing patients to seek additional follow-up.[26] This assessment can be made from radiographs taken as part of regular dental care.

Management of obesity

Obesity is a serious public health challenge because obesity is a risk factor for many diseases, particularly type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Conversely, successful weight loss is associated with important health benefits. Oral health providers are experienced in delivering nutrition and carbohydrate intake messages. With appropriate training, they can actively participate in programs aimed at weight reduction.[27]

Identifying child abuse

Child abuse has serious physical and psychosocial consequences which adversely affect the health and overall well-being of a child. Among health professionals, dentists are probably in the most favorable position to recognize child abuse, with opportunities to observe and assess not only the physical and the psychological condition of the children, but also the family environment.[28] Pediatric dentists can provide valuable information and assistance to physicians about oral and dental aspects of child abuse and neglect.

Early diagnosis and treatment of human immunodeficiency virus

Early diagnosis and treatment of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) not only improve individual outcomes, but can also reduce the spread of disease by increasing patient awareness and deceasing viral load.[29] Screening for HIV has been shown to be feasible in the dental setting. Although HIV screening can readily be conducted in the dental setting, it is not yet clear if undiagnosed HIV is sufficiently prevalent in dental patients to warrant routine screening. For example, a screening was conducted on more than 3000 previously-undiagnosed individuals presenting to a dental clinic and detected only 19 new cases of HIV.[6]

Indian Scenario Regarding Primary Care in Dental Profession

For a population of over 1.2 billion, there are currently over 180,000 dentists, which include 35,000 specialists practicing in different disciplines in the country. The dentist population ratio is reported to be 1:9000 dentists in metros/urban and semi urban areas and 1:200,000 dentists in the rural area. There are more than 35,000 dental specialists in different disciplines. The number of dentists is expected to grow to 300,000 by 2018 and the dental specialists to 50,000. Every year, more than 24,500 dental graduates are added to the list.[30]

According to a survey conducted among dental students in central India, 70% of the students had not been trained in global health ethics and most of the students were not aware about the primary health care strategy created by World Health Organization which is essential to deliver primary care in underserved populations. The findings indicate a need for global oral health course among dental students in central India.[31]

A study was conducted in a dental college in India to know the prevalence of hypertension in dental out-patient population in the Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology before they were referred to various departments to avail needed treatment. The findings revealed that 12.2% of the previously undiagnosed patients were hypertensive.[32] Screening of such hypertensive patients can thus lead to preventive systemic health care, beyond dental care. Reports of another study conducted among dental students of a private dental school in India suggested that more than half of the students were interested in knowing about obesity during their study course.[33] More than 97% of dental graduates of a dental institution in India were willing to participate in tobacco cessation activities if they are provided an opportunity.[34] Surprisingly, more than 50% of dentists practicing in an Indian city were not confident in imparting tobacco cessation counseling to their patients.[35]

Supporting Primary Care Physicians

In many developing counties like India, primary care physicians and dentists practice in cities and treat the affluent part of the urban population. This has led to the shortage of health care professionals and physicians in rural areas. It has become difficult for the poor urban and the rural population to get access to emergency and primary care. Community-oriented health promotion programs are seldom found.[36] One solution to this shortage of primary care physicians, therefore, is to increase the utilization of existing paramedical health care providers, especially dentists, who by re-distributing tasks, in their dental clinics to include screening for chronic diseases could help alleviate this shortage and improve the health of the Indian rural population. This can be tackled by employing a primary health care approach in dentistry.[36]

Dentists Collaborating with Primary Care Physicians

There has been a growing sentiment among the dental and medical community that better integration and coordination between medicine and dentistry would be beneficial. Integrating and collaborating primary care with oral health can be explained on the basis of logical reasons. Perhaps the most obvious benefit would be an increase in the effectiveness and efficiency of both dental and primary care professionals in preventing disease. By sharing information, providing basic diagnostic services, and consulting one another in a systematic and sustained manner, dental and primary care professionals in integrated practice arrangements would have a far better chance of identifying disease precursors and underlying conditions in keeping with a patient-centered model of care. Integration can also raise patients’ awareness of the importance of oral health, potentially aiding them in taking advantage of dental services sooner rather than later.[37]

Working in collaboration can also potentially improve chronic disease management and prevention. For example, research shows that there is at least a correlational association between atherosclerotic vascular disease and periodontal disease. Integration of dental and primary care also can help overcome patient-specific barriers to accessing services. For example, patient apprehension and anxiety regarding dental visits are a common experience for many people and act as a barrier to seeking ongoing dental care. Collaboration also makes sense from a cost-savings, perspective, given the linkages between dental other chronic diseases.[37]

A Curriculum for Primary Care in Dentistry

Today, a majority of a dentist's time is spent on direct provision of care, with relatively little time spent on patient evaluation and interaction with other health professions. The goal of educating dentists as members of health care teams will require fundamental changes to dental education.[38] There is a need to modify the existing curriculum of dental education with respect to primary care dentistry. The dental curriculum should have a holistic and community-oriented approach to training students. Salient recommendations are as follows:[39] (1) Changing the admissions process to attract to dentistry those most qualified for primary care; (2) substantially increasing the amount of behavioral science in the dental curriculum; (3) placing curricular emphasis initially on diagnosis and expanding the competence of the primary care dentist in endodontics, periodontics, pedodontics, orthodontics, and prevention; (4) initiating student group practice as the vehicle for patient care; (5) including intra-disciplinary and interdisciplinary training as integral components of primary care curricula; (6) extending the curriculum; (7) establishing general practice or primary care residencies either as an intra-curricular experience or as a postdoctoral requirement; (8) reorganizing dental school clinics and clinical training to reflect primary care curricular goals; (9) making more rational use of existing auxiliaries, the eventual goal being auxiliaries who perform most of the routine functions; and (10) ultimately integrating dentistry into medicine so that the future primary care practitioner receives both medical and dental training.

Special Care Dentistry: A Professional Challenge

As professionals, we have a responsibility to ensure that the oral health needs of individuals and groups who have a physical, sensory, intellectual, medical, emotional or social impairment or disability are met. Adults with a disability often have poorer oral health, poorer health outcomes, and poorer access to services than the rest of the population. To fulfill this task, it is suggested that therefore should be a networking of dentists with special interests and primary dental care practitioners. A skilled workforce that can address the wider needs of people requiring special care dentistry should be formally recognized and developed within the country to ensure that the needs of the most vulnerable sections of the community are addressed in future.[40]

Public Health Value of the Addressed Topic

Adding basic primary care procedures to a dentists’ practices can be of significant benefit to first two levels of prevention-primary prevention of prevailing health problems by communication, early diagnosis, assessment of risk factors, or immunization to prevent the spread of disease; secondary prevention to avoid or reduce later complications of systemic disease.[6] Primary prevention refers to the identification and counseling of risk factors for systemic disease, such as smoking, alcohol abuse, and obesity, before the disease occurs. All of these problems can be helped by counseling from a health care professional which could be an appropriately trained dentist. Secondary prevention refers to preventing complications of existing disease by early diagnosing and treatment. This includes various procedures which can be conducted inside the dental office and have been addressed already in the paper. For those patients who do not generally utilize health care services and are likely to only be seen in a dental office for emergency situations, health care screenings may be performed at these visits. Here, the health benefits may be modest, but this novel concept would increase the number of contact points for these dental patients with the health care system.[21] This will also broaden dentists’ role beyond the provision and supervision of oral care to the provision of limited preventive care.

Conclusion

The above discussion suggests the need to re-examine the role of dentists and dental professionals in general health care. That is, oral health care can be re-conceptualized as part of primary health care services. The introduction of primary health care activities into the dental office will benefit patients who now routinely seek dental services (and who also utilize medical care services). As such, dentists have the opportunity to provide care that extends beyond the traditional boundaries of dental services. The introduction of certain primary health care activities as part of routine dental care can better ensure that dentists effectively manage the oral health care needs of their patients. At the same time, overall patient health may improve as primary care activities undertaken during dental visits may lead to appropriate referrals to other parts of the health care system.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Primary care in Alberta - Primary care initiative [monograph on the internet] Edmonton. 2014. [Last cited on 2014 Jul 12]. Available from: http://www.albertapci.ca .

- 2.Rieselbach RE, Feldstein DA, Lee PT, Nasca TJ, Rockey PH, Steinmann AF, et al. Ambulatory training for primary care general internists: Innovation with the affordable care act in mind. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6:395–8. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-14-00119.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wright B, Nice AJ. Variation in local health department primary care services as a function of health center availability. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2014 doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Douglass CW, Shanmugham JR. Primary care, the dental profession, and the prevalence of chronic diseases in the United States. Dent Clin North Am. 2012;56:699–730. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Assael LA. Should dentists become ‘oral physicians’? No, dentistry must remain dentistry. J Am Dent Assoc. 2004;135:439. 441, 443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giddon DB, Swann B, Donoff RB, Hertzman-Miller R. Dentists as oral physicians: The overlooked primary health care resource. J Prim Prev. 2013;34:279–91. doi: 10.1007/s10935-013-0310-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McKernan SC, Kuthy RA, Kavand G. General dentist characteristics associated with rural practice location. J Rural Health. 2013;29(Suppl 1):s89–95. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lamster IB. Preface. Primary health care in the dental office. Dent Clin North Am. 2012;56:ix. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sherman P, Moscou S, Dang-Vu C. The primary care crisis and health care reform. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2009;20:944–50. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.New opportunities for dentistry in diagnosis and primary health care: Report of panel 1 of the Macy study. J Dent Educ. 2008;72:66–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ward RE, Jamison PL, Allanson JE. Quantitative approach to identifying abnormal variation in the human face exemplified by a study of 278 individuals with five craniofacial syndromes. Am J Med Genet. 2000;91:8–17. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(20000306)91:1<8::aid-ajmg2>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fox K. Who calls the shots? Illinois dentists advocate to administer flu and other vaccines. ADA News. 2013;1:8. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Creanor S, Millward BA, Demaine A, Price L, Smith W, Brown N, et al. Patients’ attitudes towards screening for diabetes and other medical conditions in the dental setting. Br Dent J. 2014;216:e2. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2013.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stacey F, Heasman PA, Heasman L, Hepburn S, McCracken GI, Preshaw PM. Smoking cessation as a dental intervention – Views of the profession. Br Dent J. 2006;201:109–13. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4813829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lamster IB, Wolf DL. Primary health care assessment and intervention in the dental office. J Periodontol. 2008;79:1825–32. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.080124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rindal DB, Rush WA, Schleyer TK, Kirshner M, Boyle RG, Thoele MJ, et al. Computer-assisted guidance for dental office tobacco-cessation counseling: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44:260–4. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Warnakulasuriya S. Effectiveness of tobacco counseling in the dental office. J Dent Educ. 2002;66:1079–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller PM, Ravenel MC, Shealy AE, Thomas S. Alcohol screening in dental patients: The prevalence of hazardous drinking and patients’ attitudes about screening and advice. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137:1692–8. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rochford C, Milles M. A review of the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of allergic reactions in the dental office. Quintessence Int. 2011;42:149–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giddon DB, Assael LA. Should dentists become “oral physicians”? J Am Dent Assoc. 2004;135:438–49. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2004.0208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lamster IB, Eaves K. A model for dental practice in the 21st century. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:1825–30. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berman CL, Van Stewart A, Ramazzotto LJ, Davis FD. High blood pressure detection: A new public health measure for the dental profession. J Am Dent Assoc. 1976;92:116–9. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1976.0338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hughes CT, Thompson AL, Collins MA. Blood pressure assessment practices of dental hygienists. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2006;7:55–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Padma A, Ramakrishnan N, Narayanan V. Management of obstructive sleep apnea: A dental perspective. Indian J Dent Res. 2007;18:201–9. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.35833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kelsey JL, Lamster IB. Influence of musculoskeletal conditions on oral health among older adults. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:1177–83. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.129429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jeffcoat M. The association between osteoporosis and oral bone loss. J Periodontol. 2005;76:2125–32. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.11-S.2125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for obesity in adults: Recommendations and rationale. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:930–2. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-11-200312020-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mathur S, Chopra R. Combating child abuse: The role of a dentist. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2013;11:243–50. doi: 10.3290/j.ohpd.a29357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Campo J, Cano J, del Romero J, Hernando V, del Amo J, Moreno S. Role of the dental surgeon in the early detection of adults with underlying HIV infection/AIDS. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2012;17:e401–8. doi: 10.4317/medoral.17527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mumbai: 2014. [Last cited on 2014 Jul 17]. Healthcare and Dental Industry in India. Indian Dental Association [monograph on the internet] Available from: http://www.fdi2014.org.in/PDF/Dental%20Industry%20in%20India.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singh A, Purohit B. Global oral health course: Perception among dental students in central India. Eur J Dent. 2012;6:295–301. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sikkerimath SB, Ramesh DN. Study on the Prevalence of Hypertension in the Dental Out-Patient Population. J Indian Acad Oral Med Radiol. 2010;22:77–80. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kumar S, Tadakamadla J, Tibdewal H, Duraiswamy P, Kulkarni S. Dental student's knowledge, beliefs and attitudes toward obese patients at one dental college in India. J Educ Ethics Dent. 2012;2:80–4. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Binnal A, Rajesh G, Denny C, Ahmed J. Insights into the tobacco cessation scenario among dental graduates: An Indian perspective. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13:2611–7. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.6.2611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chandrashekar J, Manjunath BC, Unnikrishnan M. Addressing tobacco control in dental practice: A survey of dentists’ knowledge, attitudes and behaviours in India. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2011;9:243–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tandon S. Challenges to the oral health workforce in India. J Dent Educ. 2004;68:28–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Returning the mouth to the body: Integrating oral health and primary care. Issue Brief (Grantmakers Health) 2012:1–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Battrell A, Lynch A, Steinbach P, Bessner S, Snyder J, Majeski J. Advancing education in dental hygiene. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2014;14(Suppl):209–21.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jebdp.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rovin S. A curriculum for primary care dentistry. J Dent Educ. 1977;41:176–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gallagher JE, Fiske J. Special care dentistry: A professional challenge. Br Dent J. 2007;202:619–29. doi: 10.1038/bdj.2007.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]