Abstract

Background:

Family Medicine occupies a prominent place in the undergraduate curriculum of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka. The one month clinical attachment during the fourth year utilizes a variety of teaching methods. This study evaluates teaching learning methods and learning environment of this attachment.

Methodology:

A descriptive cross sectional study was carried out among consenting students over a period of six months on completion of the clinical attachment using a pretested self administered questionnaire.

Results:

Completed questionnaires were returned by 114(99%) students. 90.2% were satisfied with the teaching methods in general while direct observation and feed back from teachers was the most popular(95.1%) followed by learning from patients(91.2%), debate(87.6%), seminar(87.5%) and small group discussions(71.9%). They were highly satisfied with the opportunity they had to develop communication skills (95.5%) and presentation skills (92.9%). Lesser learning opportunity was experienced for history taking (89.9%), problem solving (78.8%) and clinical examination (59.8%) skills. Student satisfaction regarding space within consultation rooms was 80% while space for history taking and examination (62%) and availability of clinical equipment (53%) were less. 90% thought the programme was well organized and adequate understanding on family medicine concepts and practice organization gained by 94% and 95% of the students respectively.

Conclusions:

Overall student satisfaction was high. Students prefer learning methods which actively involve them. It is important to provide adequate infra structure facilities for student activities to make it a positive learning experience for them.

Keywords: Evaluation, family medicine, learning, teaching, undergraduate

Introduction

The foundation for teaching and learning of family medicine for undergraduates was laid in Sri Lanka in the year 1983[1] and a limited clinical exposure was introduced to the curriculum of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Colombo. Family medicine was introduced to the undergraduate curriculum of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Kelaniya in early 1990s[1] and other medical faculties in the country have also incorporated this discipline into their curricula.[2]

Family medicine has bloomed gradually in the University of Kelaniya since then. The curriculum was revised in a stepwise manner guided by student feedback and program evaluations conducted from time to time and the current curriculum includes 12 lectures and two small group discussions (SGD) scheduled in the 3rd year and a clinical attachment of 1 month duration in the 4th year of the 5 year curriculum. By 4th year, students complete at least one rotation in each of the other medical disciplines namely internal medicine, general surgery, pediatrics, obstetrics and gynecology and psychiatry and at least some of the sub-specialties, for example ophthalmology and otolaryngology. On the other hand, most of the basic and applied science modules are being covered by then.

During this attachment, students are exposed to primary medical care in three settings: University Family Medicine Clinic (UFMC), general practices in the community and the out-patient department (OPD) at the nearby teaching hospital. Students are based mainly at the UFMC. The UFMC delivers its services free of charge to patient attending the clinic from surrounding areas.

At the commencement of the clerkship each student is given a study guide containing learning objectives, teaching learning activities, learning resources, details of assessment and work sheets to record learning experiences. At the UFMC, they are exposed to a variety of teaching and learning experiences. Patients who consent for participation in teaching are assigned to students. Students are expected to take a history, examine their patients and think about a possible plan of management before that patient is seen by a doctor. Subsequently, management of this patient is observed and discussed during the actual consultation where teaching takes place in a one-to-one basis. This arrangement facilitates active participation of the student and high level of supervision and constructive feedback by the trainer. Students learn consultation skills through observation and active participation during consultation. They are given opportunities, on an individual basis, to elicit histories from patients, convey information, share decisions and arrange follow-up plans appropriately. Similarly, clinical examination skills are learned through observation and performing examination under the supervision of the teacher. Student could learn procedural skills, like blood pressure measurement, use of peak flow meter, ophthalmoscope and auroscope. In addition, they receive hands-on experience in documentations such as writing prescriptions and referral letters, requesting investigations and record keeping, especially in the general practice setting. Kogan et al. concluded following a literature review that direct observation of medical trainees with actual patients by clinical supervisors is critical for teaching and assessing clinical and communication skills.[3]

Practical demonstrations are held on clinical skills such as ear-nose-throat examination, recording an electrocardiogram, nebulization, vision assessment after which they get the opportunity to practice them. Each student should complete the checklist of clinical skills [Box 1] during the attachment.

Box 1.

Checklist

A SGD [Box 2] is held every day following the clinical training to discuss family medicine concepts, common clinical conditions seen in general practice and symptom evaluation and management in primary care.

Box 2.

SGD topics

From the very beginning, on a roster basis, students are engaged in the activities at the reception desk. The student who is assigned to the reception desk on a particular day is expected to register patients, open medical records, update records and direct patients to wherever necessary. This provides an opportunity for students to gather hands-on experience and familiarize with the roles of other members of the practice staff. This exposure may help them to appreciate, even at undergraduate level, the importance of multidisciplinary involvement in patient management and practice management.

During this attachment students visit the general practices of the extended faulty staff on three Saturdays where they are exposed to primary care in the community. Two students are allocated to a general practitioner (GP). They learn by observing consultations, taking histories, examining patients and discussing subject matters with their GP tutors.

At the general practice each student log 3 consecutive patients in the recording sheet given to them. They are also expected to write a detailed account of a patient “case write-up” to demonstrate family medicine principles involved in the management of that particular patient.

Log entries by all students will be pooled together to provide an overall picture of the spectrum of problems seen in family practice. The data is summarized and presented at the seminar under three topics; patient profile - age and sex distribution, reason for encounter, problem definition and management (pharmacological and non-pharmacological) of the patient. Students also should observe the lay out and organization of the practice they visit and make a presentation at this seminar.

This seminar is held at the end of the attachment and students make presentations, discuss and share their learning experience with GPs in the community.

During their two visits to the OPD of the nearby teaching hospital they are expected to identify a patient visiting the OPD at the point of registration and be with him/her throughout their visit until they leave the hospital premises. They are expected to study differences between a family practice and an OPD and think of measures to improve the care given at an OPD.

A thoroughly enjoyed learning activity is the debate. A topic and instructions on debating is given 1 week prior to the event. The aim of this activity is to stimulate students to critically think and appreciate the strengths and weaknesses of general practice care and other sources of primary care.

Assessment of students is as important as the course content and the nature of the assessment tends to motivate and guide what and how students learn.[2] Direct observation and feedback, the checklist and work sheets where students make log entries during the GP visits are the in course and formative assessment methods incorporated into this attachment. In course formative assessments are being increasingly recognized as improving effective learning as well as monitoring student progress.[4] A review of literature by Fromme et al. concluded that direct observation is a unique and useful tool in the assessment of medical students and assessing learners in natural settings offers the opportunity to see beyond what they know and into what they actually do.[5] By observing and assessing learners with patients and providing feedback, trainers could help trainees to acquire and improve skills.[6] A Committee on Medical Education and Accreditation has also recommended on-going assessment that includes direct observation of trainees’ clinical skills.[7]

The checklist specially is an indication of the level of clinical experience and competence achieved by the student and it's a means of self-assessment to student. The written assessment which comprised of two structured essay questions to be answered within a ½ h duration contributes to the final summative assessment at the end of the academic year.

This study was planned to evaluate this attachment by exploring student views on teaching and learning methods, learning environment and availability of resources for their training with a view to identify successes and failures of the attachment. The outcome will be of benefit to other medical schools already incorporated and planning to introduce family medicine/general practice training programs to students.

Methodology

This descriptive cross-sectional study was carried out among consenting students over a period of 6 months in 2011on completion of the clinical attachment using a pre-tested self-administered feedback form.

Close-ended questions which the responses were put into Likert scale, evaluated the students’ satisfaction on teaching learning methods, learning environment and resources. Questionnaire was administrated on completion of the student's assessment. A brief introduction was given and the questionnaires were distributed among the students. The consenting students were requested to place the completed questionnaire in a sealed box which was opened after the completion of their final assessment in family medicine at the end of the 4th year.

Data was analyzed using SPSS 16 version (SPSS Incorporated, USA).

Results

Completed questionnaires were submitted by 114 students with a response rate of more than 99%.

Vast majority (90%) had a clear idea about the learning outcomes of the clinical appointment and 93% acknowledged the importance of previously learnt factual information and skills to maximize the benefits of the clinical attachment.

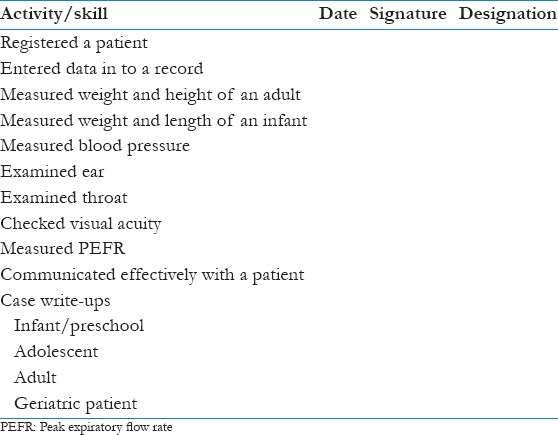

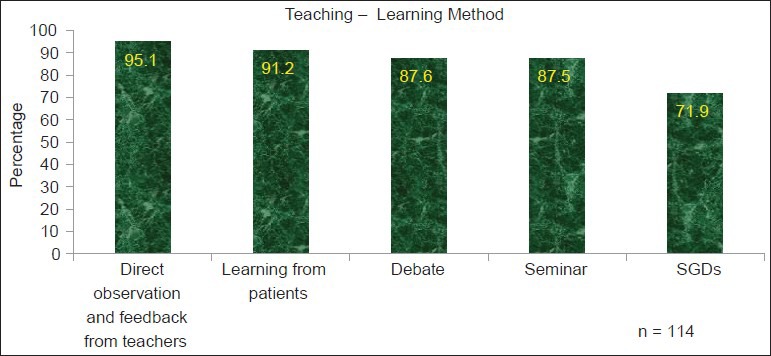

Nearly 90.2% were satisfied with the teaching methods in general. Students’ preference for individual teaching learning methods is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Preference in teaching learning methods

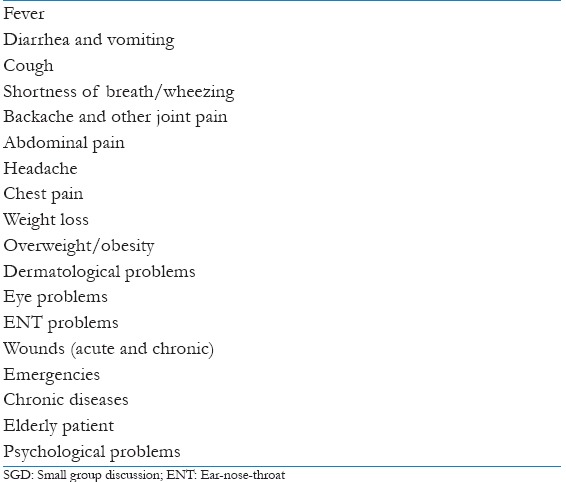

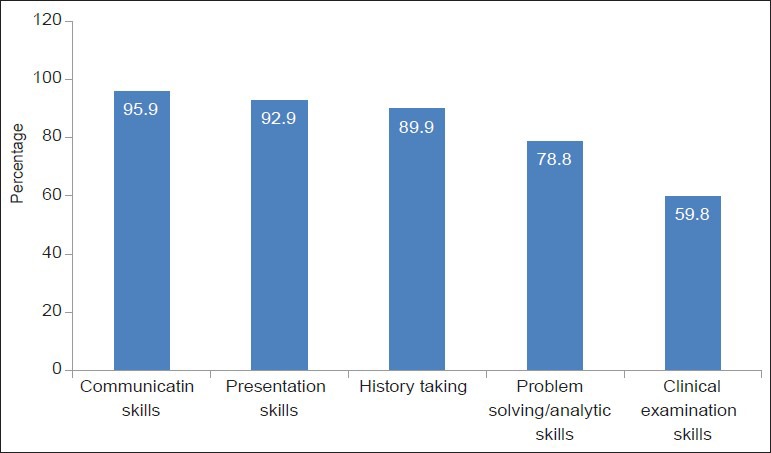

Figures 2 and 3 show the opportunity they had to learn different skills.

Figure 2.

Opportunity to develop skills

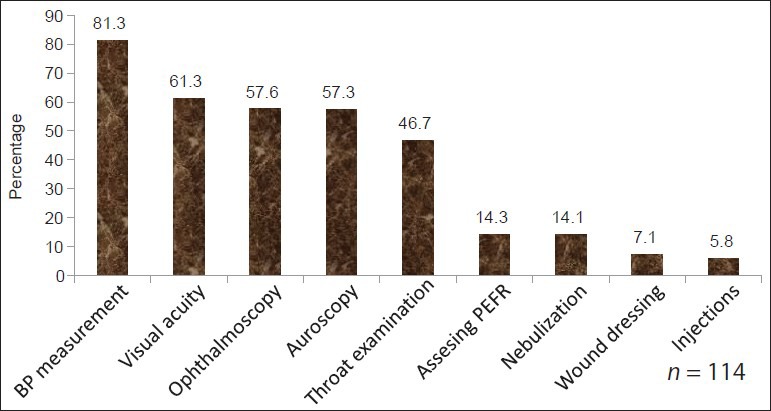

Figure 3.

Opportunity for examination skills/procedures

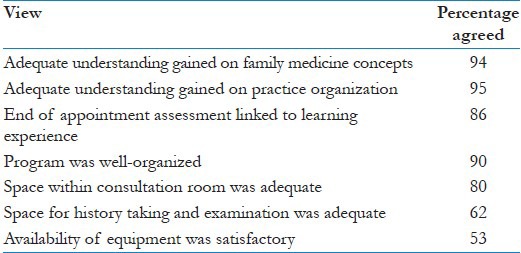

Following Table 1 shows their views on other aspects of the attachment.

Table 1.

Student views on other aspects of the attachment

Discussion

Student feedback is extremely important to assess if students have achieved particular objectives of a training program. Such a feedback helps to design, develop, construct and strengthen training programs[8] and improve the quality of teaching and learning and beneficial to students, faculty and institution alike.[9] Evaluation helps in guiding and monitoring course changes as well.

This study was conducted at the end of the clinical attachment but before the final assessment which is held at the end of the academic year. Researches attempted to overcome a possible bias in student feedback by requesting them to place the completed questionnaire without any identification link in a sealed box and by informing them that it would be opened only after the release of the results of the summative assessment at the end of the academic year.

It is encouraging that students had a clear idea about the learning outcomes of the attachment. If students learn without having an understanding of the objectives they will not be able to engaged in focused learning to acquire desired knowledge and skills. Study guide which students receive on the 1st day spells out the learning objectives for each setting. By the expression of 90% students in this study shows that one of the objectives of providing a study guide has been achieved. Therefore providing a document with the objectives, learning outcomes and details of the program at the beginning is a successful strategy in informing students of the objectives.

Previously achieved knowledge and skills have helped them to learn family medicine. This is an important revelation since it gives the correct idea of the discipline to students as well. Family medicine is a specialty in breath which encompasses almost all the other branches of medicine but at a different level (primary care) and at a different depth. One of the objectives of this attachment is to train students to apply knowledge and skills gathered from other disciplines for management of patients at primary care level.

It's an encouragement that the vast majority (92%) appreciated the teaching methods in general.

Students have shown to prefer teaching-learning methods which involve their active participation. Direct observation and teachers’ feedback on their consultations with patients had the highest rating. This has been shown in similar studies. In a study of general practice attachment in Scotland, students conducting their own consultations was the most valued activity[10] and a study conducted at the Faculty of Medicine, Colombo, Sri Lanka also highlighted the value of supervised patient consultations.[11] Grant and Michael Robling revealed that students valued one-to-one teaching in their study conducted in UK.[12] Kalantan et al.[13] has identified lack of student involvement in the consultation as a reason for poor student satisfaction. Students preferred learning from interacting with patients, seminar and debate but there was a relatively low rating for SGDs. It's an eye-opener for teachers and SGDs should be planned and conducted in a more meaningful manner.

In our study, learning opportunities for practical skills are significantly low except for a few basic skills. Poor opportunities to perform or improve procedural skills in general practice settings has been a constant finding in many other studies conducted in different parts of the world.[13,14,15] One reason for this could be the fact that patients spend only a limited time in an outpatient set up in contrast to patients in a ward where students get ample opportunities to sharpen their skills. Other reason may be the non-availability of adequate number of equipment which students have revealed in this study.

Students have gained adequate understanding of family medicine concepts and practice organization, which are the main objectives of the attachment. Students have endorsed the way the program was organized. Program for the entire month is prepared at the beginning and its available to students as well as teachers. Since both groups are aware of teaching and learning activities beforehand they can prepare for their tasks in advance.

Students have expressed dissatisfaction over the space available for them to interact with patients. However, they are satisfied with the space in the consultation room. When planning a teaching practice it's important to ensure adequate space for student activities. Similarly, equipment also should be available in adequate numbers to facilitate student learning.

Students have agreed that the end of attachment assessment was linked to their learning experience. This may be due to two facts. Teachers were mindful and have selected and set questions in relation to learning objectives and the past questions would have guided them to acquire specific knowledge.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Overall student satisfaction was at a higher level. Direct observation and feedback from teachers was the most popular. Emphasis should be placed on retaining and further strengthening participatory based learning methods preferred by students

Intervention is needed to obtain adequate clinical equipment and improve facilities in the learning environment

More learning opportunities need to be created to enhance acquisition of clinical skills. This may be a difficult task considering the hurdles and knowledge emanating from other studies. Students should be encourage to practice and acquire these clinical skills from other clinical attachments and skills lab.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.De Silva N. Family medicine in the undergraduate curriculum: Teaching and learning. Sri Lanka Fam Physician. 1997;20:3–16. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramanayake RP. Historical evolution and present status of family medicine in Sri Lanka. J Family Med Prim Care. 2013;2:131–4. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.117401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kogan JR, Holmboe ES, Hauer KE. Tools for direct observation and assessment of clinical skills of medical trainees: A systematic review. JAMA. 2009;302:1316–26. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lefford F, McCrorie P, Perrin F. A survey of medical undergraduate community-based teaching: Taking undergraduate teaching into the community. Med Educ. 1994;28:312–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1994.tb02718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fromme HB, Karani R, Downing SM. Direct observation in medical education: A review of the literature and evidence for validity. Mt Sinai J Med. 2009;76:365–71. doi: 10.1002/msj.20123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duffy FD, Gordon GH, Whelan G, Cole-Kelly K, Frankel R, Buffone N, et al. Assessing competence in communication and interpersonal skills: The Kalamazoo II report. Acad Med. 2004;79:495–507. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200406000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Program Requirements for Resident Education in Internal Medicine. [Last accessed on 2013 Dec 03]. Available from: http://www.acgme.org/acwebsite/downloads/RRC_progReq/140_internal_medicine_07012009.pdf .

- 8.Kern DE, Thomas PA, Hughes MT, editors. 2nd ed. Maryland, USA: John Hopkins University Press; 2009. Curriculum Development for Medical Education: A Six-Step Approach. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Astin AW, Anthonio AL. 2nd ed. Rowman and Little Field; 2012. Assessment for Excellence. The Philosophy and Excellence of Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education. The Ace Series on Higher Education. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morrison J, Murray TS. What do students want to do during a general practice attachment? Educ Gen Pract. 1996;7:136–41. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olupeliyawa A, Karunthilaka I, Goonaratne K, Munasinghe R, De Abrew A, Ediriweera E. Colombo, Sri Lanka: University of Colombo; 2008. Student perceptions of a programme in family medicine at the faculty of medicine, Abstract Book International Medical Education Conference 2008, Faculty of Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grant A, Robling M. Introducing undergraduate medical teaching into general practice: An action research study. Med Teach. 2006;28:e192–7. doi: 10.1080/01421590600825383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalantan K, Pyrne N, Al-Faris E, Al-Taweel A, Al-Rowais N, Abdul Ghani H, et al. Students’ perceptions towards a family medicine attachment experience. Educ Health (Abingdon) 2003;16:357–65. doi: 10.1080/13576280310001607622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith SR, MacLeod NM. An innovative family medicine clerkship. J Fam Pract. 1981;13:687–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cooper CW. Medical students’ perceptions of an undergraduate general practice preceptorship. Fam Pract. 1992;9:323–9. doi: 10.1093/fampra/9.3.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]