Abstract

Background:

Acinetobacter is clinically important pathogen with widespread resistance to various antibiotics. We assessed the incidence of Acinetobacter infection at a tertiary care hospital, analyze their resistance pattern and identify the production of extended spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) and metallo β-lactamases (MBLs).

Materials and Methods:

The study was conducted in tertiary care hospital, India over a period of 2 years. Acinetobacter species were isolated from various clinical samples received in Department of Microbiology. After identification, Acinetobacter isolates were speciated and antibiotic susceptibility was determined by the standard disc diffusion method. ESBL and MBL production was detected by the double disc synergy test and combined disc diffusion test respectively.

Results:

Of 3298 infected samples, 111 (3.36%) were found to be Acinetobacter. The most predominant species was Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-A. baumannii (Acb) complex (72%). High incidence of resistance was recorded for piperacillin (55%), followed by ceftriaxone (46%) and ceftazidime (46%). Isolation rate and antibiotic resistance was higher in the Intensive Care Units (ICUs) of the hospital. ESBL and MBL production was detected in 31.5% and 14.4% of the isolates respectively.

Discussion and Conclusion:

A high level of antibiotic resistance was observed in our study and maximum isolation rate of Acinetobacter was in the ICUs. Acb complex was the most predominant and most resistant species. The analysis of susceptibility pattern will be useful in understanding the epidemiology of this organism in our hospital setup, which will help in treating individual cases and controlling the spread of resistant isolates to other individuals.

Keywords: Acb complex, Acinetobacter spp., Antibiotic resistance, intensive care units

INTRODUCTION

Acinetobacter species are saprophytic, ubiquitous and have emerged as an important nosocomial pathogen due to its ability for survival in the hospital environment on a wide range of dry and moist surfaces.[1] Human infections caused by Acinetobacter species include pneumonia, which is most often related to endotracheal tubes or tracheostomies, endocarditis, meningitis, skin and wound infections, peritonitis in patients receiving peritoneal dialysis, UTI and bacteremia.[2,3]

Antibiotic susceptibility pattern of Acinetobacter may vary widely geographically and between various units of the same hospital at various time points. The variations in Acinetobacter resistogram, necessitates a periodic surveillance of these pathogens to achieve appropriate selection of therapy.[4,5] Due to unpredictable multidrug resistance patterns of clinical strains of Acinetobacter, it is imperative to know the institutional prevalent susceptibility profiles. Hence, this study was conducted to isolate the Acinetobacter species from various clinical samples by a simplified phenotypic identification protocol and to determine the antibiotic susceptibility pattern of these isolates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

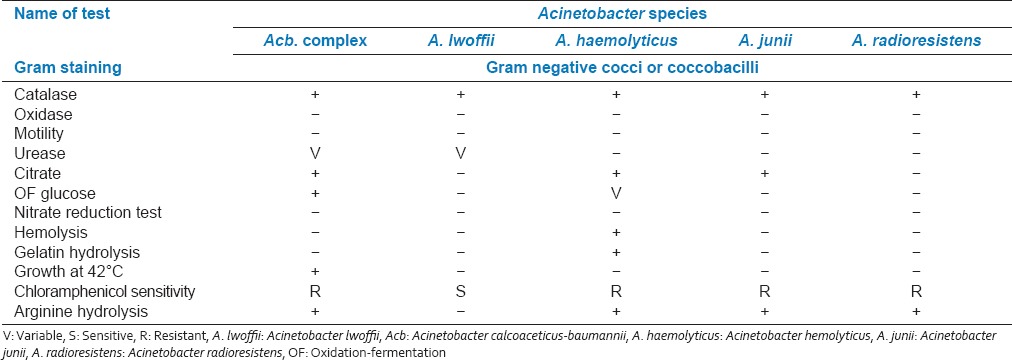

The study was conducted in the Department of Microbiology over a period of 2 years. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of our institute (Padmashree Dr. D.Y Patil Medical College and Research Center). A total of 6007 clinical specimens received in the Department of Microbiology for culture and sensitivity from indoor and outdoor patients were included in the study. Samples were processed for culture by standard conventional methods and susceptibility testing were determined by Kirby Bauers disc diffusion method.[2,5,6] Antibiotics and their strength used was according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines: Piperacillin (100 μg), ceftazidime (30 μg), ceftriaxone (30 μg), cefotaxime (30 μg), cefepime (30 μg), ciprofloxacin (5 μg), imipenem (10 μg) amikacin (30 μg).[6] Genus Acinetobacter was identified by Gram staining, cell and colony morphology, positive catalase test, negative oxidase test and absence of motility.[5] Speciation of Acinetobacter was performed on the basis of glucose oxidation, gelatin liquefaction, beta hemolysis, growth at 37°C and 42°C, arginine hydrolysis and susceptibility to chloramphenicol [Table 1].[1,7,8,9,10,11]

Table 1.

Phenotypic characteristics of Acinetobacter species

Detection of Extended spectrum β-lactamases production

The double disc synergy test (DDST) was used to determine the prevalence of extended spectrum β-lactamases (ESBL) production in Acinetobacter as per previously reported protocols.[7,12,13]

Detection of metallo β-lactamases production

Two 10 μg imipenem discs were placed on a lawn culture of the isolates to be tested and 10 μl of 0.5 M ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) (750 μg of disodium salt, dehydrate) solution was added to one IMP disc. The zone of inhibition around IMP discs alone and those with EDTA were compared after 16-18 h. An increase in zone size of at least 7 mm around the IMP-EDTA disc when compared to IMP disc alone was recorded as a positive result.[14]

RESULTS

Of the total 6007 samples, 3298 (55%) were found to be culture positive. Of the 3298 positive culture, Gram-negative bacteria were 1376 (42%). Of total Gram-negative organisms, 291 (21%) were nonfermenters and the isolation rate of Acinetobacter from total nonfermenters was 111 (38%). Out of total culture positive samples, 111 (3.36%) infections were found to be due to Acinetobacter. Acinetobacter species were predominantly isolated from blood samples 41 (36.9%) followed by pus 25 (22.5%), respiratory samples 16 (14.4%), urine 13 (11.7%), other body fluids 10 (9%) and various catheter tips 6 (5.4%). Maximum Acinetobacter species isolated were from Intensive Care Units (ICUs) 42 (38%) followed by surgery ward 22 (20%), medicine ward 16 (14%), orthopedics ward 12 (11%), pediatric ward 11 (10%), gynecology ward 4 (4%) and out patients department 4 (4%). Statistically significant difference was noted in infections in ICU caused by other nonfermenters 29 (16.1%) and Acinetobacter species 42 (37.8%). In the present study, maximum isolated species were Acb (Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-A. baumannii) complex (80 [72%] of total Acinetobacter isolates), non-Acb complex (Acinetobacter lwoffii 16 (14%), Acinetobacter haemolyticus 13 (12%), Acinetobacter junii 1 (1%), Acinetobacter radioresistans 1 (1%). Acinetobacter haemolyticus species were predominantly found in pus samples. There was a higher incidence of infection among males. Acinetobacter infection was more common in patients in age group >50 years (31 [28%]) followed by <10 years (26 [23%]). Infection in neonates was higher within 14 days postpartum. Isolation rate of Acinetobacter species was maximum (52 [46.84%]) during July to September period (95% confidence interval (37.39-56.51)). The disc diffusion susceptibility testing shows the percentages of resistance and sensitivity among all isolates. Maximum resistance was recorded for piperacillin 61 (55%), ceftriaxone 51 (46%), ceftazidime 51 (46%), cefepime 49 (44%), cefotaxime 48 (43%), amikacin 47 (42%), ciprofloxacin 26 (23%) and imipenem 24 (22%).

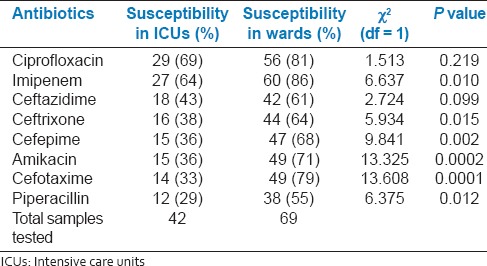

Of 111 isolates of Acinetobacter species, 35 (31.5%) were found to be producing ESBL by the DDST with one or more of the cephalosporins used. A total of 16 (14.4%) isolates were metallo β-lactamases (MBL) producers by combined disc diffusion test. The statistically increased resistance of antibiotics for ICUs isolates in comparison to wards isolates was analyzed by Chi-square test [Table 2]. Of 111 isolates, 44 (39.63%) isolates were multidrug resistant strains (isolates resistant to at least one agent in three or more antimicrobial categories-penicillins, cephalosporins, aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones, and carbapenems).[15,16]

Table 2.

Comparison of antibiotic susceptibility in ICUs and wards

DISCUSSION

Acinetobacter is a nosocomial pathogen. Its ability to infect healthy hosts and its propensity to develop antimicrobial drug resistance is a cause for concern among infectious disease specialty. Acinetobacter isolated from normal skin and mucous membranes are reported to cause serious and sometimes fatal infections.[17] In our study, Acinetobacter accounted for 38% of total nonfermenters and 3.36% of total positive cultures. Pseudomonas spp. was the most common nonfermenter isolated in our study. Previously, published studies have accounted 12.9%[10] and 4.8%[5] of Acinetobacter isolates from total infected samples, respectively. In various countries, studies on Acinetobacter isolation have shown predominance in urine (21-27%) and tracheobronchial secretions (24.8-48.8%)[10] nevertheless there is an increase in occurrence of Acinetobacter in hemocultures in some hospital departments.[11] Bacteremia due to Acinetobacter occur most frequently in critically ill patients particularly admitted in ICUs as these patients usually require prolonged hospital stay, need repeated invasive procedures and frequently receive treatment with broad spectrum antimicrobials.[18] In our study, maximum Acinetobacter isolates were from blood samples and from ICUs, which is consistent with previous reports.[19] We also observed that the infection was common in patients of age group >50 years followed by 0-10 years age group. In the study by Mindolli et al.[1] isolates Acinetobacter were in age group >45 years possibly due to weakened immune system and associated chronic diseases in these age groups. In this study, maximum resistance was observed to piperacillin (55%), followed by ceftriaxone (46%) and ceftazidime (46%). Rahbar et al.[20] found high rate of resistance to A. baumannii for ceftriaxone (90.9%), piperacillin (90.9%), ceftazidime (84.1%), ciprofloxacin (90.9%) and imipenem was the most effective antibiotic, which is consistent with our observation. Maximum resistance was observed in ICU isolates in comparison to wards where Acb complex was most prevalent. In ICUs most sensitive drug was ciprofloxacin (69%) followed by imipenem (64%). In their study Shakibaie et al.[21] they found that many isolates of Acinetobacter species were resistant to almost all antibiotics routinely used in the ICUs of their hospital. There is limited data on β-lactamase producing Acinetobacter species from India. In our study, 31.5% of Acinetobacter species were ESBL producer by the DDST and14.4% were MBL producers by the combined disc diffusion test. Kansal et al.[22] and Kumar et al.[23] found the 75% of ESBL producing and 21% of MBL producing isolates in their study respectively. Due to different antimicrobial susceptibility pattern in different hospitals, these surveillance studies are valuable in deciding the most adequate therapy for Acinetobacter infections. In our study, 44 (39.6%) isolates were MDR strains. Acinetobacter appears to have a propensity to develop antibiotic resistance extremely rapidly, perhaps as a consequence of its long term evolutionary exposure to antibiotic producing organisms in soil environment.[24] The emergence of antibiotic resistant strains in ICUs is because of higher use of antimicrobial agents per patient and per surface area.[18] Acinetobacter species obtained were maximum during July to September period, which is consistent with previous reports.[25,26,27] The reason for this seasonality correlated with atmospheric temperature changes (high isolation rates especially in regions where temperature is hot and humid). Nevertheless, it is essential to periodically perform such prevalence and sensitivity assays as it will help clinicians in better management of Acinetobacter infections.

CONCLUSION

The occurrence of Acinetobacter species among nonfermenters is high in hospital settings. Rationale use of antibiotics is important and necessary to prevent microbial resistance catastrophe. Definitive identification and characterization of ESBLs can only be confirmed by molecular techniques. However, these techniques are not available in all laboratories. Therefore simple phenotypic methods can be used to recognize these enzymes. Resistant antibiotic after sensitivity report should be discontinued and in place a sensitive drug should be given. A continued awareness of the need to maintain good housekeeping and control of the environment, including equipment decontamination, strict attention to hand washing should undertake to control the spread of Acinetobacter in hospitals.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mindolli PB, Salmani MP, Vishwanath G, Hanumanthapa AR. Identification and speciation of Acinetobacter and their antimimicrobial susceptibility testing. Al Ameen J Med Sci. 2010;3:3459. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winn WC, Allen SD, Janda WM, Koneman EW, Procop GW, Schreckenberger PC, et al. Taxonomy, biochemical characteristics and clinical significance of medically important nonfermenters. In: Darcy P, Peterson N, editors. Koneman's Colour Atlas and Textbook of Diagnostic Microbiology. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2006. pp. 353–5. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oberoi A, Aggarwal A, Lal M. A decade of underestimated nosocomial pathogen-Acinetobacter in a tertiary care hospital in Punjab. JK Sci. 2009;11:24–6. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prashanth K, Badrinath S. In vitro susceptibility pattern of Acinetobacter species to commonly used cephalosporins, quinolones, and aminoglycosides. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2004;22:97–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lone R, Shah A, Kadri SM, Lone S, Shah F. Nosocomial multi-drug resistant Acinetobacter infections-clinical findings, risk factors and demographic characteristics. Bangladesh J Med Microbiol. 2009;03:34–8. [Google Scholar]

- 6.CLSI document M100-S17. Wayne, PA, USA: CLSI; 2007. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; Seventeenth Informational Supplement. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sinha M, Srinivasa H, Macaden R. Antibiotic resistance profile & extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) production in Acinetobacter species. Indian J Med Res. 2007;126:63–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koneman EW, Allen SD, Janda WM, Schreckenberger PC, Winn WC. The nonfermentative gram negative bacilli. In: Allen A, Deitch S, editors. Colour Atlas and Textbook of Diagnostic Microbiology. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott -Raven Publishers; 1997. pp. 253–309. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baron EJ, Peterson LR, Finegold SM. Nonfermentative gram negative bacilli and coccobacilli. In: Shanahan JF, Potts LM, Murphy C, editors. Bailey and Scott's Diagnostic Microbiology. 9th ed. St. Louis, Missouri: Mosby-Year Book; 1994. pp. 386–4. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lahiri KK, Mani NS, Purai SS. Acinetobacter spp as nosocomial pathogen: Clinical significance and antimicrobial sensitivity. Med J Armed Forces India. 2004;60:7–10. doi: 10.1016/S0377-1237(04)80148-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hejnar P, Kolár M, Hájek V. Characteristics of Acinetobacter strains (phenotype classification, antibiotic susceptibility and production of beta-lactamases) isolated from haemocultures from patients at the Teaching Hospital in Olomouc. Acta Univ Palacki Olomuc Fac Med. 1999;142:73–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gupta V. An update on newer beta-lactamases. Indian J Med Res. 2007;126:417–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fallon RJ, Young H. Neisseria, Moraxella, Acinetobacter. In: Collee JG, Fraser AG, Marimon BP, Simmons A, editors. Mackie % McCartney Practical Medical Microbiology. 14th ed. India: Elsevier; 2007. p. 294. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saha R, Jain S, Kaur IR. Metallo beta-lactamase producing Pseudomonas species — A major cause of concern among hospital associated urinary tract infection. J Indian Med Assoc. 2010;108:344–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, Carmeli Y, Falagas ME, Giske CG, et al. Multidrug resistant, extensively drug resistant and pandrug resistant bacteria: An international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:268–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adams-Haduch JM, Paterson DL, Sidjabat HE, Pasculle AW, Potoski BA, Muto CA, et al. Genetic basis of multidrug resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates at a tertiary medical center in Pennsylvania. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:3837–43. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00570-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pal RB, Kale VV. Acinetobacter calcoaceticus — An opportunistic pathogen. J Postgrad Med. 1981;27:218–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cisneros JM, Rodríguez-Baño J. Nosocomial bacteremia due to Acinetobacter baumannii: Epidemiology, clinical features and treatment. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2002;8:687–93. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2002.00487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seifert H, Strate A, Pulverer G. Nosocomial bacteremia due to Acinetobacter baumannii. Clinical features, epidemiology, and predictors of mortality. Medicine (Baltimore) 1995;74:340–9. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199511000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rahbar M, Mehrgan H, Aliakbari NH. Prevalence of antibiotic-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in a 1000-bed tertiary care hospital in Tehran, Iran. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2010;53:290–3. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.64333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shakibaie MR, Adeli S, Salehi MH. Antibiotic resistance patterns and extended-spectrum β-lactamase production among Acinetobacter spp. isolated from an intensive care Unit of a hospital in Kerman, Iran. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2012;1:1. doi: 10.1186/2047-2994-1-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kansal R, Pandey A, Asthana AK. Beta-lactamase producing Acinetobacter species in hospitalized patients. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2009;52:456–7. doi: 10.4103/0377-4929.55035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar AV, Pillai VS, Dinesh KR, Karim S. The phenotypic detection of carbapenemase in meropenem resistant Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-baumannii complex in a tertiary care hospital in south India. J Clin Diagn Res. 2011;5:223–6. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manchanda V, Sanchaita S, Singh N. Multidrug resistant Acinetobacter. J Glob Infect Dis. 2010;2:291–304. doi: 10.4103/0974-777X.68538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McDonald LC, Banerjee SN, Jarvis WR. Seasonal variation of Acinetobacter infections: 1987-1996.Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:1133–7. doi: 10.1086/313441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Joshi SG, Litake GM, Satpute MG, Telang NV, Ghole VS, Niphadkar KB. Clinical and demographic features of infection caused by Acinetobacter species. Indian J Med Sci. 2006;60:351–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fournier PE, Richet H. The epidemiology and control of Acinetobacter baumannii in health care facilities. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:692–9. doi: 10.1086/500202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]