Abstract

Background:

Microbial resource orchid is a collection of Gram-positive and Gram-negative clinical isolates sourced from different hospitals and diagnostic laboratories in India. We determined the antibiotic susceptibility of a set of Gram-negative Enterobacteriaceae and non-fermenter clinical isolates from microbial resource orchid, collected during the period of 2002-2012 against commonly used antibiotics.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 247 Gram negative strains consisting of 142 Enterobacteriaceae and 105 non-fermenters from microbial resource orchid were selected for determining minimum inhibitory concentration against β-lactams, aminoglycosides, quinolone, and tetracycline by agar dilution method as per clinical and laboratory standards institute guidelines.

Results:

All the isolates had high resistance to ampicillin, piperacillin, ceftazidime, gentamicin, tetracycline, and ciprofloxacin. Pseudomonas aeruginosa showed moderate resistance to carbapenems.

Conclusion:

This study demonstrated the high level of antibiotic resistance among the strains collected under microbial resource orchid and further, such data and the strains can be used in new chemical entities profiling.

Keywords: Antibiotic susceptibility, antibiotic resistance, Gram-negative clinical isolates, minimum inhibitory concentration

INTRODUCTION

There is a constant global increase in the prevalence of Gram-negative infections especially in the Intensive Care Units (ICUs). A multi-national study found that there was a worrisome shift toward Gram-negative infections with 62% of the collected microbial isolates from ICUs.[1] Infectious Diseases Society of America has highlighted a faction of antibiotic resistant bacteria Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterobacter spp.,[2] which predominantly consist of Gram-negative bacteria.

Multi-drug resistance to commonly used antibiotics among clinically important Gram-negative pathogens is on the rise. The production of extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) or AmpC-type β-lactamase by these pathogens causes resistance to most β-lactam antibiotics and is often associated with resistance to aminoglycosides and fluoroquinolones.[3] Carbapenems have been the last resort in treatment of serious multi-drug resistant Gram-negative bacterial infections. However, there is an increase in carbapenem resistance in P. aeruginosa and emergence of carbapenem resistance in Enterobacteriaceae.[4,5,6]

Antibiotic susceptibility data of clinical isolates are helpful to understand the epidemiology of antibiotic resistant bacteria and to choose the effective antibiotic for treating such pathogens. In addition, a collection of such isolates are useful in evaluating antibacterial potency of pipeline new chemical entities (NCEs) in discovery research. Orchid sources different Gram-positive and Gram-negative clinical isolates from various hospitals and diagnostic laboratories in India and maintains it under the name of microbial resource orchid. These isolates are maintained for the purpose of evaluating potential antibacterial NCEs. Before such evaluation, susceptibility pattern of these isolates to commonly used antibiotics should be identified. In the present study, we determined the antibiotic susceptibility of a set of Gram-negative Enterobacteriaceae and non-fermenter clinical isolates from microbial resource orchid, collected during the period of 2002-2012 against commonly used antibiotics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolates

A selected set of Gram-negative clinical isolates from microbial resource orchid collection, comprising of Escherichia coli (n = 58), Klebsiella sp., (n = 58) Enterobacter sp., (n = 26) P. aeruginosa (n = 83), and A. baumannii (n = 22) were included in the study. These isolates were sourced from several tertiary hospitals in India and were isolated from wound swab, pus, vaginal swab, urine, ear swab, sputum, tracheal aspirate, bronchial lavage, catheter tip, blood, and cerebrospinal fluid. These isolates were speciated with the MiniAPI automated culture identification system (BioMerieux, France) and were preserved in brain heart infusion (BHI) (BD, USA) broth containing 20% glycerol at −80°C. Isolates were revived on BHI agar plates that were incubated overnight at 37°C. On the day of the experiment, to obtain log phase in broth, cultures were inoculated into BHI broth and incubated at 37°C for 4-6 h. E. coli ATCC 25922 and P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 were the quality control strains used in the study.

Antibiotics

Various antibiotics included in the study were sourced from commercial batches belonging to β-lactam, aminoglycoside, quinolone, and tetracycline classes and β-lactamase inhibitors (BLI).

Determination of minimum inhibitory concentration

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of antibiotics and β-lactam/BLI combinations (ampicillin/sulbactam, piperacillin/tazobactam, and ceftazidime/tazobactam) was determined by agar dilution method according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines.[7] Mueller — Hinton agar (MHA) (BD, USA) plates, each containing a doubling concentrations of antibiotics were prepared. Tazobactam was combined at a fixed concentration of 4 mg/L and ampicillin/sulbactam was added at 2:1 ratio. The MHA plates were inoculated with cultures diluted to approximately 104 CFU/spot. MIC was determined as the lowest concentration of the drug which inhibited the visible growth of the isolates after an incubation period of 18 h at 37°C.

RESULTS

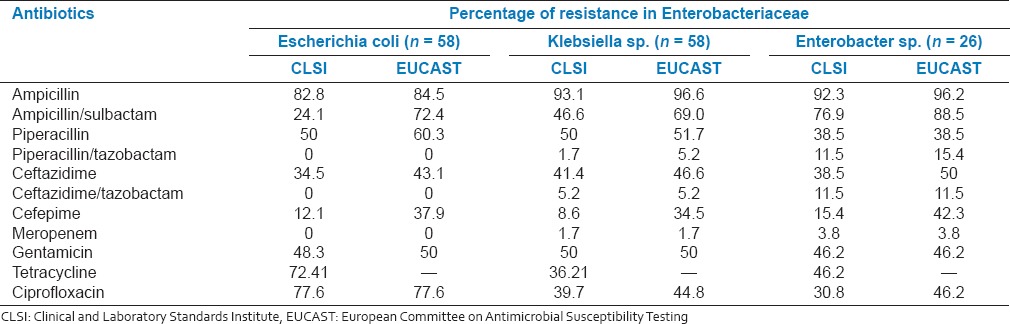

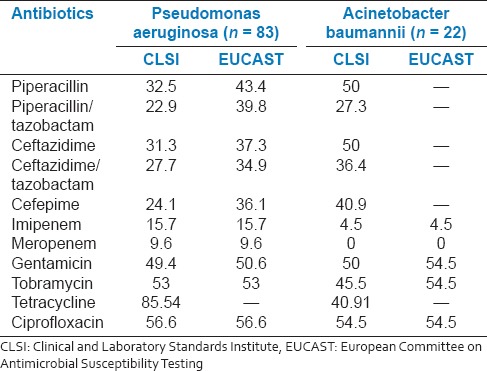

The percentage of antibiotic resistance in microbial resource orchid clinical isolates is represented in Tables 1 and 2. The percentage resistance was determined based on both CLSI and European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing breakpoints. For the interpretation of data and discussion, we followed CLSI breakpoints as these are widely followed.

Table 1.

Percentage resistance in Enterobacteriaceae clinical isolates

Table 2.

Percentage resistance in non-fermenters clinical isolates

Escherichia coli isolates showed higher level of resistance to ampicillin (82.8%) followed by ciprofloxacin (77.6%) and tetracycline (72.4%). In addition, there was a significant resistance observed against piperacillin (50%), gentamicin (48.3%), and ceftazidime (34.5%). Meropenem, piperacillin/tazobactam, and ceftazidime/tazobactam showed no resistance.

In Klebsiella sp., a high level of resistance to ampicillin (93.1%) followed by resistance to piperacillin and gentamicin (50%); ceftazidime, ciprofloxacin and tetracycline (36-41%) was observed. There was a marginal resistance to ceftazidime/tazobactam (5.2%) and piperacillin/tazobactam and meropenem (1.7%). Similar trend was observed in Enterobacter sp., except that, there was a moderate resistance to piperacillin/tazobactam and ceftazidime/tazobactam (11.5%).

Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates showed significant to moderate resistance to all the tested drugs. There was a significant resistance to tetracycline (85.5%), followed by ciprofloxacin, tobramycin and gentamicin (49-56%); piperacillin and ceftazidime (32%) and moderate resistance to imipenem (15.7%) and meropenem (9.6%). A. baumannii exhibited resistance to ciprofloxacin (54.5%), piperacillin, ceftazidime, gentamicin (50%), tobramycin (45.5%), tetracycline, and cefepime (40.9%).

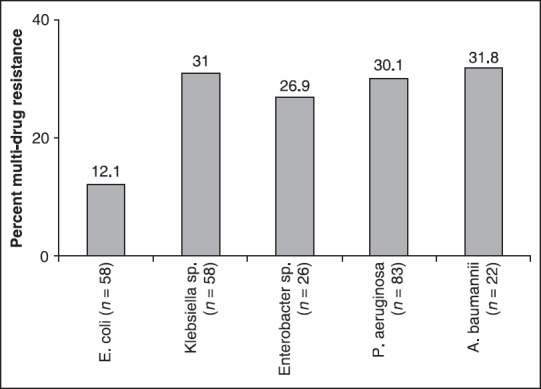

With respect to multi-drug resistance among the microbial resource orchid clinical isolates, about 30% of Klebsiella sp. were resistant to ampicillin, ciprofloxacin, gentamicin, and tetracycline. Both P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii had a similar level of multi-drug (piperacillin, ciprofloxacin, gentamicin, and tetracycline) resistant phenotypes [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Percentage of multi-drug resistance in Enterobacteriaceaea and nonfermentersb. aResistant to ampicillin, ciprofloxacin, gentamicin, and tetracycline, bResistant to piperacillin, ciprofloxacin, gentamicin, and tetracycline

DISCUSSION

The susceptibility data of microbial resource orchid Enterobacteriaceae and non-fermenter clinical isolates demonstrated remarkable resistance to commonly used antibiotics.

In Enterobacteriaceae, there was a significant resistance to β-lactams (except cefepime and meropenem), ciprofloxacin, gentamicin, and tetracycline. In addition, notable percentages of the isolates were multi-drug resistant. Similar resistance pattern among Indian Enterobacteriaceae clinical isolates have been widely reported.[8] In the present study, tazobactam, an inhibitor of β-lactamases including ESBLs was combined with ceftazidime to assess the prevalence of ESBL producers. Among ceftazidime resistant isolates, all E. coli and majority of Klebsiella and Enterobacter were susceptible to ceftazidime combined with tazobactam suggesting that they were ESBL producers.

Another important finding of the study was carbapenem resistance in P. aeruginosa isolates. Apart from resistance displayed against piperacillin, ciprofloxacin, and gentamicin, there was a notable resistance to both imipenem and meropenem. Since both these agents have been the last resort in treatment of serious P. aeruginosa infections in hospitals, increased resistance to them requires serious attention. Combining tazobactam to piperacillin and ceftazidime against their resistance strains did not significantly reduce the resistance level suggesting such strains possessed either AmpC β-lactamase or non β-lactamase mediated resistance mechanisms. In addition, there was significant multi-drug resistance both in P. aeruginosa and A. baumannii.

Inappropriate and overuse of antibiotics has been implicated for antibiotic resistance development in bacterial pathogens.[9] This study and other published studies showed that the initial choice of treatment of antibiotic resistant Gram-negative infections is carbapenems.[10] However, there has been the emergence of resistance to carbapenems,[11] which was also observed in the present study. Hence, implementing policy for rational use of antibiotics is essential to minimize the emergence and spread of resistance. In addition, there is an urgent need for generating pipeline NCEs which are effective against multi-drug resistant pathogens. By representing current epidemiological pattern, microbial resource orchid isolates can be used in evaluating antibacterial potency and spectrum of pipeline NCEs in discovery research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Orchid Chemicals and Pharmaceuticals Limited, for providing the financial support.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vincent JL, Rello J, Marshall J, Silva E, Anzueto A, Martin CD, et al. International study of the prevalence and outcomes of infection in intensive care units. JAMA. 2009;302:2323–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pendleton JN, Gorman SP, Gilmore BF. Clinical relevance of the ESKAPE pathogens. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2013;11:297–308. doi: 10.1586/eri.13.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kallen AJ, Hidron AI, Patel J, Srinivasan A. Multidrug resistance among gram-negative pathogens that caused healthcare-associated infections reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network, 2006-2008. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31:528–31. doi: 10.1086/652152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castanheira M, Bell JM, Turnidge JD, Mathai D, Jones RN. Carbapenem resistance among Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains from India: Evidence for nationwide endemicity of multiple metallo-β-lactamase clones (VIM-2, -5, -6, and -11 and the newly characterized VIM-18) Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:1225–7. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01011-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gupta N, Limbago BM, Patel JB, Kallen AJ. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: Epidemiology and prevention. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:60–7. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nordmann P, Naas T, Poirel L. Global spread of Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1791–8. doi: 10.3201/eid1710.110655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.CLSI document M100-S18. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2008. CLSI. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: 18th informational supplement. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sarma JB, Bhattacharya PK, Kalita D, Rajbangshi M. Multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae including metallo-ß-lactamase producers are predominant pathogens of healthcare-associated infections in an Indian teaching hospital. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2011;29:22–7. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.76519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.English BK, Gaur AH. The use and abuse of antibiotics and the development of antibiotic resistance. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;659:73–82. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-0981-7_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rahal JJ. The role of carbapenems in initial therapy for serious Gram-negative infections. Crit Care. 2008;12(Suppl 4):S5. doi: 10.1186/cc6821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta E, Mohanty S, Sood S, Dhawan B, Das BK, Kapil A. Emerging resistance to carbapenems in a tertiary care hospital in north India. Indian J Med Res. 2006;124:95–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]