Abstract

Teeth are the most natural, noninvasive source of stem cells. Dental stem cells, which are easy, convenient, and affordable to collect, hold promise for a range of very potential therapeutic applications. We have reviewed the ever-growing literature on dental stem cells archived in Medline using the following key words: Regenerative dentistry, dental stem cells, dental stem cells banking, and stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth. Relevant articles covering topics related to dental stem cells were shortlisted and the facts are compiled. The objective of this review article is to discuss the history of stem cells, different stem cells relevant for dentistry, their isolation approaches, collection, and preservation of dental stem cells along with the current status of dental and medical applications.

Keywords: Cell culture techniques, stem cells, stem cell research, tissue banks, tissue engineering

INTRODUCTION

Regenerative capacity of the dental pulp is well-known and has been recently attributed to function of dental stem cells. Dental stem cells offer a very promising therapeutic approach to restore structural defects and this concept is extensively explored by several researchers, which is evident by the rapidly growing literature in this field. For this review article a literature research covering topics related to dental stem cells was made and the facts are compiled.

METHODS

A web-based research on Medline (www.pubmed.gov) was done. To limit our research to relevant articles, the search was filtered using terms review, published in the last 10 years and dental journals. Various keywords used for research were “regenerative dentistry” (128 articles found), “dental stem cells” (111 articles found), “dental stem cells banking” (2 articles found), “stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth (SHED)” (11 articles found). For each heading in the review, relevant articles were chosen and arranged in chronological order of publication date so as to follow the development of the research topic. This review screened about 250 articles to get the required knowledge update. Relevant data were then compiled with aim of providing basic information as well as latest updates on dental stem cells.

HISTORY OF STEM CELLS

Stem cells also known as “progenitor or precursor” cells are defined as clonogenic cells capable of both self-renewal and multi-lineage differentiation.[1] In 1868, the term “stem cell” for the first time appeared in the works of German biologist Haeckel.[2] Wilson coined the term stem cell.[3] In 1908, Russian histologist, Alexander Maksimov, postulated existence of hematopoietic stem cells at congress of hematologic society in Berlin.[4] There term “stem cell” was proposed for scientific use.

Stem cells have manifold applications and have contributed to the establishment of regenerative medicine. Regenerative medicine is the process of replacing or regenerating human cells, tissues or organs for therapeutic applications.[5] The concept of regeneration in the medical field although not new has significantly advanced post the discovery of stem cells and in recent times have found its application in dentistry following identification of dental stem cells. Although, the concept of tooth regeneration was initially not accepted the ground-breaking work by stomatologist G. L. Feldman (1932) showed evidence of regeneration of dental pulp under certain optimal biological conditions. This work introduced the biological-aseptic principle of tooth therapy to achieve pulp regeneration using dentine fillings as building material for stimulating pulp regeneration.[6] Nevertheless subsequent researchers further improved this work.[6] Major breakthrough in dental history was achieved in year 2000 when Gronthos et al. identified and isolated odontogenic progenitor population in adult dental pulp.[7] These cells were referred to as dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs). Since this discovery several researchers have reported varieties of dental stem cells, which are described below:

DENTAL STEM CELLS

Human dental stem cells that have been isolated and characterized are:

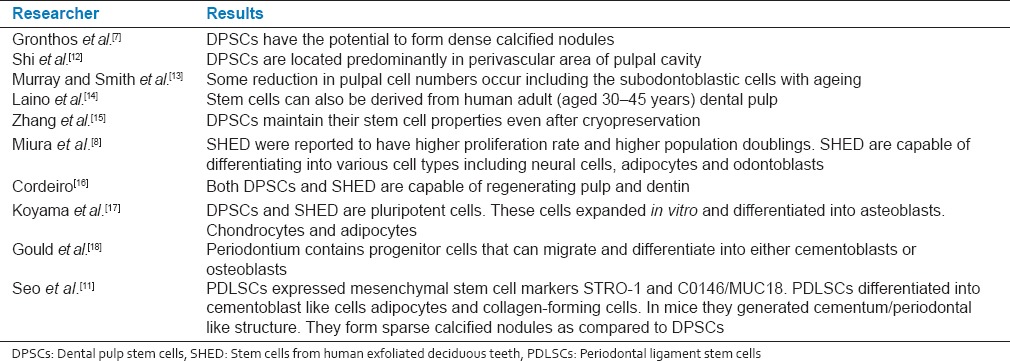

Stem cells from various sources and their features studied by various researchers are presented in Table 1.[7,8,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]

Table 1.

Stem cells and their features studied by various researchers (at full page width)

Dental pulp stem cells

DPSCs are mesenchymal type of stem cells inside dental pulp.[19] DPSCs have osteogenic and chondrogenic potential in vitro and can differentiate into dentin, in vivo and also differentiate into dentin-pulp-like complex.[7] Recently, immature dental pulp stem cells[20] were identified which are a pluripotent sub-population of DPSC generated using dental pulp organ culture.

DPSCs are putative candidate for dental tissue engineering due to:[21]

Easy surgical access to the collection site and very low morbidity after extraction of the dental pulp.

DPSCs can generate much more typical dentin tissues within a short period than nondental stem cells.

Can be safely cryopreserved and recombined with many scaffolds.

Possess immuno-privilege and anti-inflammatory abilities favorable for the allotransplantation experiments.

Identification of dental pulp stem cells

Four commonly used stem cell identification techniques[22] are:

Fluorescent antibody cell sorting: Stem cells can be identified and isolated from mixed cell populations by staining the cells with specific antibody markers and using a flow cytometer.

Immunomagnetic bead selection.

Immunohistochemical staining.

Physiological and histological criteria, including phenotype, proliferation, chemotaxis, mineralizing activity and differentiation.

Isolation approaches of dental pulp stem cells

Various conventional methods to isolate stem cells from dental pulp are listed below:

Size-sieved isolation

Enzymatic digestion of whole dental pulp tissue in solution of 3% collagenase Type I for 1 h at 37°C is done. Through process of filtering and seeding, cells with diameter between 3 and 20 μm are obtained for further culture and amplification. Based on this approach, small-sized cell populations containing a high percent of stem cells can be isolated.

Stem cell colony cultivation

Enzymatic digestion of the dental pulp tissue is done to prepare single cell suspension cells of which are used for colony formation containing 50 or more cells that is further amplified for experiments.

Magnetic activated cell sorting (MACS)

Is an immune-magnetic method used for separation of stem cell populations based on their surface antigens (CD271, STRO-1, CD34, CD45, and c-Kit). MACS is technically simple, inexpensive and capable of handling large numbers of cells but the degree of stem cell purity is low.

Fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS)

Is convenient and efficient method that can effectively isolate stem cells from cell suspension based on cell size and fluorescence. Demerits of this technique are a requirement of expensive equipment, highly-skilled personnel, decreased viability of FACS-sorted cells and this method is not appropriate for processing bulk quantities of cells.

Stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth

Dr. Songtao Shi discovered SHED in 2003. Miura et al.[8] confirmed that SHED were able to differentiate into a variety of cell types to a greater extent than DPSCs, including osteoblast-like, odontoblast-like cells, adipocytes, and neural cells. Abbas et al.[23] investigated the possible neural crest origin of SHED. The main task of these cells seems to be the formation of mineralized tissue, which can be used to enhance orofacial bone regeneration.

Types of stem cells present in human exfoliated deciduous teeth are

Adipocytes: Can be used to treat various spine and orthopedic conditions, Crohn's disease, cardiovascular diseases and may also be useful in plastic surgery.[24]

Chondrocytes and osteoblasts: Have been used to grow intact teeth in animals.[8]

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs): Have successfully been used to repair spinal cord injury and to restore feeling and movement in paralyzed human patients. They can also be used to treat neuronal degenerative disorders such as Parkinson's disease, cerebral palsy, Alzheimer's disease, and other such disorders. MSCs have better curative potential than other type of adult stem cells.[8]

Advantages of banking SHED cells[25] include: It's a simple painless technique to isolate them and being an autologous transplant they don’t possess any risk of immune reaction or tissue rejection and hence immunosuppressive therapy is not required. SHED may also be useful for close relatives of the donor such as grandparents, parents and siblings. Apart from these, SHED banking is more economical when compared to cord blood and may be complementary to cord cell banking. The most important of all these cells are not subjected to same ethical concerns as embryonic stem cells.

Collection, isolation, and preservation of stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth

Step 1: Tooth collection

Freshly-extracted tooth is transferred into vial containing hypotonic phosphate buffered saline solution (up to four teeth in one vial). Vial is then carefully sealed and placed into thermette, after which the carrier is placed into an insulated metal transport vessel. Thermette along with insulated transport vessel maintains the sample in a hypothermic state during transportation. This procedure is described as sustentation. The time from harvesting to arrival at processing storage facility should not exceed 40 h.

Step 2: Stem cell isolation

Tooth surface is cleaned by washing three times with Dulbecco's phosphate buffered saline without Ca2+ and Mg2+. Disinfection is done and again washed with PBSA. Pulp tissue is isolated from the pulp chamber and is placed in a sterile petri dish, washed at least three times with PBSA. The tissue digestion is done with collagenase Type I and dispase for 1 h at 37°C. Isolated cells are passed through a 70 um filter to obtain single cell suspensions. Then the cells are cultured in a MSC medium. Usually isolated colonies are visible after 24 h.

Step 3: Stem cell storage.

The approaches used for stem cell storage are: (a) Cryopreservation (b) magnetic freezing.

Cryopreservation

It is the process of preserving cells or whole tissues by cooling them to sub-zero temperatures. Cells harvested near end of log phase growth (approximately. 80–90% confluent) are best for cryopreservation. Liquid nitrogen vapour is used to preserve cells at a temperature of <−150°C. In a vial 1.5 ml of freezing medium is optimum for 1–2 × 106 cells.

Magnetic freezing

This technology is referred to as cells alive system (CAS), which works on principle of applying a weak magnetic field to water or cell tissue which will lower the freezing point of that body by up to 6–7°C. Using CAS, Hiroshima University (first proposed this technology) claims that it can increase the cell survival rate in teeth to 83%. CAS system is a lot cheaper than cryogenics and more reliable.

Criteria of tooth eligibility for stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth banking

Primary incisors and canines with no pathology and at least one third of root left can be used for SHED banking. Primary molar roots are not recommended for sampling as they take longer time to resorb, which may result in an obliterated pulp chamber that contains no pulp, and thus, no stem cells.[26] However in some cases where deciduous molars are removed early for orthodontic reasons, it may present an opportunity to use these teeth for stem cell banking.

Stem cells from apical papilla (SCAP)

MSCs residing in the apical papilla of permanent teeth with immature roots are known as SCAP. These were discovered by Sonoyama et al.[9] SCAP are capable of forming odontoblast-like cells, producing dentin in vivo, and are likely cell source of primary odontoblasts for the formation of root dentin. SCAP supports apexogenesis, which can occur in infected immature permanent teeth with periradicular periodontitis or abscess. SCAP residing in the apical papilla survive such pulp necrosis because of their proximity to the periapical tissue vasculature. Hence even after endodontic disinfection, SCAP can generate primary odontoblasts, which complete root formation under the influence of the surviving epithelial root sheath of Hertwig.[9]

Periodontal ligament stem cells (PDLSCs)

Seo et al.[11] described the presence of multipotent postnatal stem cells in the human periodontal ligament (PDLSCs). When transplanted into rodents, PDLSCs had the capacity to generate a cementum/periodontal ligament-like structure and contributed to periodontal tissue repair. These cells can also be isolated from cryopreserved periodontal ligaments while retaining their stem cell characteristics, including single-colony strain generation, cementum/periodontal-ligament-like tissue regeneration, expression of MSC surface markers, multipotential differentiation and hence providing a ready source of MSCs.[27]

Using a mini pig model, autologous SCAP and PDLSCs were loaded onto hydroxyapatite/tricalcium phosphate and gelfoam scaffolds, and implanted into sockets in the lower jaw, where they formed a bioroot encircled with the periodontal ligament tissue and in a natural relationship with the surrounding bone.[28] Trubiani et al.[29] suggested that PDLSCs had regenerative potential when seeded onto three dimensional biocompatible scaffold, thus encouraging their use in graft biomaterials for bone tissue engineering in regenerative dentistry, whereas Li et al.[30] have reported cementum and periodontal ligament-like tissue formation when PDLSCs are seeded on bioengineered dentin.

TOOTH STEM CELL BANKING

Although tooth banking is currently not very popular the trend is gaining acceptance mainly in the developed countries. BioEden (Austin, Texas, USA), has international laboratories in UK (serving Europe) and Thailand (serving South East Asia) with global expansion plans. Stem cell banking companies like Store –A- Tooth (Provia Laboratories, Littleton, Massachusetts, USA) and StemSave (Stemsave Inc, New York, USA) are also expanding their horizon internationally. In Japan, the first tooth bank was established in Hiroshima University and the company was named as “Three Brackets” (Suri Buraketto) in 2005. Nagoya University (Kyodo, Japan) also came up with a tooth bank in 2007. Taipei Medical University in collaboration with Hiroshima University opened the nation's first tooth bank in September, 2008. The Norwegian Tooth Bank (a collaborative project between the Norwegian Institute of Public Health and the University of Bergen) set up in 2008 is collecting exfoliated primary teeth from 1,00,000 children in Norway. Not last but the least, Stemade introduced the concept of dental stem cells banking in India recently by launching its operations in Mumbai and Delhi.

POTENTIAL APPLICATIONS IN DENTISTRY

Most research is directed toward regeneration of damaged dentin, pulp, resorbed root, periodontal regeneration and repair perforations. Whole tooth regeneration to replace the traditional dental implants is also in pipeline. Tissue-engineering applications using dental stem cells that may promote more rapid healing of oral wounds and ulcers as well as the use of gene-transfer methods to manipulate salivary proteins and oral microbial colonization patterns are promising and possible.[31]

The use of stem cells in osseous regeneration

Adult MSCs recently identified in the gingival connective tissues (gingival mesenchymal stem cells [GMSCs]) have osteogenic potential and are capable of bone regeneration in mandibular defects. GMSCs also suppress the inflammatory response by inhibiting lymphocyte proliferation and inflammatory cytokines and by promoting the recruitment of regulatory T-cells and anti-inflammatory cytokines. Thus, GMSCs potentially promote the “right” environment for osseous regeneration and is currently being therapeutically explored.[32]

Nondental stem cells for dental application

Researchers of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine, reported a possible method for growing teeth from stem cells obtained in urine.[33] In this study, pluripotent stem cells derived from human urine were induced to generate tooth-like structures in a group of mice with a success rates of up to 30%. The generated teeth had physical properties similar to that of normal human teeth except hardness (about one-third less in hardness of human teeth). The reported advantages to such an approach were being noninvasive technique, low cost, and use of somatic cells (instead of embryonic) that are wasted anyways. Interestingly urine-derived stem cells do not form tumors when transplanted in the body unlike other stem cells; more over autologous sourcing of these cells reduces the likelihood of rejection.

PROSPECTS OF DENTAL STEM CELLS IN MEDICINE

Dental stem cells have the potential to be utilized for medical applications like heart therapies,[34] regenerating brain tissue,[35] for muscular dystrophy therapies[36] and for bone regeneration.[37,38] SHED can be used to generate cartilage[39] as well as adipose tissue.[40] In 2008 first advanced animal study for bone grafting was announced resulting in reconstruction of large size cranial bone defects in rats with human DPSCs.[41]

FUTURE PROSPECTIVES

Researchers have observed promising results in several preclinical animal studies and numerous clinical trials are now on-going globally to further validate these findings. The Obama administration has made stem cell research one of the pillars of his health program. The U.S. Army is investing over $250 million in stem cell research to treat injured soldiers in a project called Armed Forces Institute for Regenerative Medicine. It is likely that the next stem cell advance is the availability of regenerative dental kits, which will enable the dentists the ability to deliver stem cell therapies locally as part of routine dental practice. An innovative method that holds promising future is to generate induced stem cells from harvested human dental stem cells. This approach reprograms dental stem cells into an embryonic state, thus expanding their potential to differentiate into a much wider range of tissue types. Researchers have so far succeeded in making specific dental tissues or tooth like structures although in animal studies but future advances in dental stem cell research will be the regeneration of functional tooth in humans.

As human stem cell research is a relatively new area, companies developing cell therapies face several types of risks as well, and some are not able to manage them thus pushing this venture into a highly speculative enterprise. Present clinical trials are being performed on recombinant human fibroblast growth factor-2, human platelet-derived growth factor, and tricalcium phosphate (GEM-21). Looking at the ongoing clinical trials, it is too early to speculate whether all therapies based on stem cells will prove to be clinically effective.[42]

CONCLUSION

Stem cells of dental origin have multiple applications nevertheless there are certain limitations as well. The oncogenic potential of these cells is still to be determined in long-term clinical studies. Moreover, the research is mainly confined to animal models and their extensive clinical application is yet to be tested. Other major limitations are the difficulty to identify, isolate, purify and grow these cells consistently in labs. Immune rejection is also one of the issues, which require a thorough consideration; nevertheless use of autologous cells can overcome this. Lastly, stem/progenitor cells are comparatively less potent than embryonic stem cells. Teeth-like structures cannot replace actual teeth, thus a considerable research research and development efforts is required to advance the dental regenerative therapeutics. Researchers still need to grow blood and nerve supply of teeth to make them fully functional. Although not currently available, these approaches may one day be used as biological alternatives to the synthetic materials currently used. Like other powerful technologies, dental stem cell research poses challenges as well as risks. If we are to realize the benefits, meet the challenges, and avoid the risks, stem cell research must be conducted under effective, accountable systems of social-responsible oversight and control, at both the national and international levels.[43]

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fischbach GD, Fischbach RL. Stem cells: Science, policy, and ethics. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1364–70. doi: 10.1172/JCI23549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yamaizumi M, Mekada E, Uchida T, Okada Y. One molecule of diphtheria toxin fragment a introduced into a cell can kill the cell. Cell. 1978;15:245–50. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90099-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson EB. 1st ed. New York: Macmillan Company; 1996. The Cell in Development and Inheritance. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maximow A. The lymphocyte as a stem cell, common to different blood elements in embryonic development and during the post-fetal life of mammals. Folia Haematol. 1909;8:123–34. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mason C, Dunnill P. A brief definition of regenerative medicine. Regen Med. 2008;3:1–5. doi: 10.2217/17460751.3.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Polezhaev LV. 1st ed. Jerusalem: Keterpress; 1972. Restoration of lost regenerative capacity of dental tissues. In: Loss and Restoration of Regenerative Capacity in Tissues and Organs of Animals; pp. 141–52. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gronthos S, Mankani M, Brahim J, Robey PG, Shi S. Postnatal human dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) in vitro and in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:13625–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.240309797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miura M, Gronthos S, Zhao M, Lu B, Fisher LW, Robey PG, et al. SHED: Stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:5807–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0937635100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sonoyama W, Liu Y, Fang D, Yamaza T, Seo BM, Zhang C, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-mediated functional tooth regeneration in swine. PLoS One. 2006;1:e79. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sonoyama W, Liu Y, Yamaza T, Tuan RS, Wang S, Shi S, et al. Characterization of the apical papilla and its residing stem cells from human immature permanent teeth: A pilot study. J Endod. 2008;34:166–71. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2007.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seo BM, Miura M, Gronthos S, Bartold PM, Batouli S, Brahim J, et al. Investigation of multipotent postnatal stem cells from human periodontal ligament. Lancet. 2004;364:149–55. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16627-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shi S, Robey PG, Gronthos S. Comparison of human dental pulp and bone marrow stromal stem cells by cDNA microarray analysis. Bone. 2001;29:532–9. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(01)00612-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murray PE, Smith AJ. Saving pulps – A biological basis. An overview. Prim Dent Care. 2002;9:21–6. doi: 10.1308/135576102322547511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laino G, d’Aquino R, Graziano A, Lanza V, Carinci F, Naro F, et al. A new population of human adult dental pulp stem cells: A useful source of living autologous fibrous bone tissue (LAB) J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:1394–402. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang W, Walboomers XF, Shi S, Fan M, Jansen JA. Multilineage differentiation potential of stem cells derived from human dental pulp after cryopreservation. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:2813–23. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.2813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cordeiro MM, Dong Z, Kaneko T, Zhang Z, Miyazawa M, Shi S, et al. Dental pulp tissue engineering with stem cells from exfoliated deciduous teeth. J Endod. 2008;34:962–9. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koyama N, Okubo Y, Nakao K, Bessho K. Evaluation of pluripotency in human dental pulp cells. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:501–6. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2008.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gould TR, Melcher AH, Brunette DM. Migration and division of progenitor cell populations in periodontal ligament after wounding. J Periodontal Res. 1980;15:20–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1980.tb00258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamamura T. Differentiation of pulpal cells and inductive influences of various matrices with reference to pulpal wound healing. J Dent Res. 1985;64:530–40. doi: 10.1177/002203458506400406. Spec No. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kerkis I, Kerkis A, Dozortsev D, Stukart-Parsons GC, Gomes Massironi SM, Pereira LV, et al. Isolation and characterization of a population of immature dental pulp stem cells expressing OCT-4 and other embryonic stem cell markers. Cells Tissues Organs. 2006;184:105–16. doi: 10.1159/000099617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yan M, Yu Y, Zhang G, Tang C, Yu J. A journey from dental pulp stem cells to a bio-tooth. Stem Cell Rev. 2011;7:161–71. doi: 10.1007/s12015-010-9155-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murray PE, Garcia-Godoy F, Hargreaves KM. Regenerative endodontics: A review of current status and a call for action. J Endod. 2007;33:377–90. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abbas, Diakonov I, Sharpe P. Neural crest origin of dental stem cells. Pan European Federation of the International Association for Dental Research (PEF IADR) Seq #96-Oral. Stem Cells. 2008 Abs, 0917. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perry BC, Zhou D, Wu X, Yang FC, Byers MA, Chu TM, et al. Collection, cryopreservation, and characterization of human dental pulp-derived mesenchymal stem cells for banking and clinical use. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2008;14:149–56. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2008.0031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arora V, Arora P, Munshi AK. Banking stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth (SHED): Saving for the future. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2009;33:289–94. doi: 10.17796/jcpd.33.4.y887672r0j703654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reznick JB. Continuing education: Stem cells: Emerging medical and dental therapies for the dental professional. Dentaltown Mag. 2008;Oct:42–53. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seo BM, Miura M, Sonoyama W, Coppe C, Stanyon R, Shi S. Recovery of stem cells from cryopreserved periodontal ligament. J Dent Res. 2005;84:907–12. doi: 10.1177/154405910508401007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang GT, Sonoyama W, Liu Y, Liu H, Wang S, Shi S. The hidden treasure in apical papilla: The potential role in pulp/dentin regeneration and bioroot engineering. J Endod. 2008;34:645–51. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trubiani O, Orsini G, Zini N, Di Iorio D, Piccirilli M, Piattelli A, et al. Regenerative potential of human periodontal ligament derived stem cells on three-dimensional biomaterials: A morphological report. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2008;87:986–93. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Y, Jin F, Du Y, Ma Z, Li F, Wu G, et al. Cementum and periodontal ligament-like tissue formation induced using bioengineered dentin. Tissue Eng Part A. 2008;14:1731–42. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2007.0268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jain A, Bansal R. Regenerative medicine: Biological solutions to biological problems. Indian J Med Spec. 2013;4:41–6. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang F, Yu M, Yan X, Wen Y, Zeng Q, Yue W, et al. Gingiva-derived mesenchymal stem cell-mediated therapeutic approach for bone tissue regeneration. Stem Cells Dev. 2011;20:2093–102. doi: 10.1089/scd.2010.0523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cai J, Zhang Y, Liu P, Chen S, Wu X, Sun Y, et al. Generation of tooth-like structures from integration-free human urine induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Regen. 2013;2:6. doi: 10.1186/2045-9769-2-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gandia C, Armiñan A, García-Verdugo JM, Lledó E, Ruiz A, Miñana MD, et al. Human dental pulp stem cells improve left ventricular function, induce angiogenesis, and reduce infarct size in rats with acute myocardial infarction. Stem Cells. 2008;26:638–45. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nosrat IV, Widenfalk J, Olson L, Nosrat CA. Dental pulp cells produce neurotrophic factors, interact with trigeminal neurons in vitro, and rescue motoneurons after spinal cord injury. Dev Biol. 2001;238:120–32. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kerkis I, Ambrosio CE, Kerkis A, Martins DS, Zucconi E, Fonseca SA, et al. Early transplantation of human immature dental pulp stem cells from baby teeth to golden retriever muscular dystrophy (GRMD) dogs: Local or systemic? J Transl Med. 2008;6:35. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-6-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Graziano A, d’Aquino R, Cusella-De Angelis MG, De Francesco F, Giordano A, Laino G, et al. Scaffold's surface geometry significantly affects human stem cell bone tissue engineering. J Cell Physiol. 2008;214:166–72. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Graziano A, d’Aquino R, Laino G, Papaccio G. Dental pulp stem cells: A promising tool for bone regeneration. Stem Cell Rev. 2008;4:21–6. doi: 10.1007/s12015-008-9013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fecek C, Yao D, Kaçorri A, Vasquez A, Iqbal S, Sheikh H, et al. Chondrogenic derivatives of embryonic stem cells seeded into 3D polycaprolactone scaffolds generated cartilage tissue in vivo. Tissue Eng Part A. 2008;14:1403–13. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2007.0293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.D’Andrea F, De Francesco F, Ferraro GA, Desiderio V, Tirino V, De Rosa A, et al. Large-scale production of human adipose tissue from stem cells: A new tool for regenerative medicine and tissue banking. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2008;14:233–42. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2008.0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Mendonça Costa A, Bueno DF, Martins MT, Kerkis I, Kerkis A, Fanganiello RD, et al. Reconstruction of large cranial defects in nonimmunosuppressed experimental design with human dental pulp stem cells. J Craniofac Surg. 2008;19:204–10. doi: 10.1097/scs.0b013e31815c8a54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saini R, Saini S, Sharma S. Therapeutics of stem cells in periodontal regeneration. J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2011;2:38–42. doi: 10.4103/0976-9668.82316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saini R, Saini S, Sharma S. Stem cell therapy: The eventual future. Int J Trichology. 2009;1:145–6. doi: 10.4103/0974-7753.58562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]